Abstract

Sandhoff disease (SD) is a fatal neurodegenerative disorder belonging to the family of diseases called GM2 Gangliosidosis. There is no curative treatment of SD. The molecular pathogenesis of SD is still unclear though it is clear that the pathology initiates with the build-up of ganglioside followed by microglial activation, inflammation, demyelination and apoptosis, leading to massive neuronal loss. In this article, we explored the expression profile of selected immune and myelination associated transcripts (Wfdc17, Ccl3, Lyz2, Fa2h, Mog and Ugt8a) at 5-, 10- and 16-weeks, representing young, pre-symptomatic and late stages of the SD mice. We found that immune system related genes (Wfdc17, Ccl3, Lyz2) are significantly upregulated by several fold at all ages in Hexb-KO mice relative to Hexb-het mice, while the difference in the expression levels of myelination related genes is not statistically significant. There is an age-dependent significant increase in expression of microglial/pro-inflammatory genes, from 5-weeks to the near humane end-point, i.e., 16-week time point; while the expression of those genes involved in myelination decreases slightly or remains unchanged. Future studies warrant use of new high-throughput gene expression modalities (such as 10X genomics) to delineate the underlying pathogenesis in SD by detecting gene expression changes in specific neuronal cell types and thus, paving the way for rational and precise therapeutic modalities.

1. Introduction

Sandhoff Disease (SD), Tay Sachs (TSD) and AB variant are lysosomal storage disorders that belong to a family of diseases called GM2 Gangliosidosis. They are fatal neurodegenerative disorders that are inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, and are caused by a genetic mutation that results in an accumulation of the incompletely metabolized GM2 mono-sialoganglioside in the lysosome of cells, especially in the central nervous system (CNS) [1,2]. The occurrence of SD is approximately 1 in 300,000 in the general population, but is increased in certain populations [3].

GM2 Gangliosidosis occurs due to a deficiency of the lysosomal enzyme β-Hexosaminidase-A (Hex A) or the GM2A Activator Protein. The X-ray crystallographic structure of Hex A has revealed that it is an αβ heterodimer [4]. The α and β subunits are encoded by HEXA and HEXB genes, respectively, [5]. Deficiency of the HEXB gene results in SD, whilst deficiency of the HEXA and GM2A Activator (GM2A) results in TSD and AB variant respectively. SD occurs in 3 forms: infantile, juvenile and adult form; with the infantile form being the most common and the most severe due to the least amount of enzyme activity [6,7].

There is no curative treatment for GM2 gangliosidosis and in several animal models, treatment modalities like enzyme replacement, substrate restriction, glucose analogs and anti-inflammatory agents have shown variable benefits [8,9]. Gene therapy and small molecule approaches are also being explored to alleviate the symptoms and lifespan of these diseases [10,11,12]. Further, to guide the development of rational and precise therapeutic approaches, specific delineation of molecular pathology in these diseases is vital.

A number of research groups have explored into the pathogenesis of GM2 Gangliosidosis, as well as its commonality among other lysosomal storage disorders. Some of the main features of the pathology include the build-up of ganglioside, microglial activation, inflammation, demyelination and apoptosis, leading to massive neuronal loss [13,14,15]. A recent microarray study on brain tissues by Ogawa and colleagues (2018) identified a number of differentially expressed genes related to inflammation and demyelination in 4-week old SD mice [16]. Here, we attempted validating a subset (Table 1) of these putative differentially regulated genes in a SD mouse model. We explored the expression profile of selected immune and myelination associated transcripts at 5-, 10- and 16-weeks, representing young, pre-symptomatic and late stages of the SD mice, to delineate the progression of the changes with age and localize their expression pattern in cerebral cortex and cerebellum, the two most affected parts of the brain.

Table 1.

NCBI IDs and gene function annotation using String database.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

All experiments were performed in accordance with Queen’s University Animal Care Committee (2017-1707). The animals used in this study were Hexb−/− (Hexb-KO) Sandhoff disease mouse model (B6;129S4-Hexbtm1Rlp, Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA). This colony is on a 12 h day/night cycle (7 to 7), in Tecniplast Green Line IVC Sealsafe cages, receiving a Laboratory Rodent Diet with water ad libitum. This mouse model abnormally accumulates GM2 and GA2 ganglioside, develop motor defects beginning at about 3 months of age. Without treatment, the defects progressively worsen and Hexb-KO mice die by 16 to 18 weeks of age.

2.2. Brain Sample Collection and RNA Extraction

Midsections of the brain (representative cerebral cortex) and cerebellum were stored in RNALater (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) at −80 °C until all samples were ready for extraction in batch. Extractions were made using GeneJet RNA Purification Kit (Thermo Fisher, Mississauga, ON, Canada) according to manufacturer’s recommendations. Genomic DNA was removed by DNase treatment. RNA was eluted with 50 μL of nuclease-free water. RNA Quality and concentration was measured using a Nanodrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RNA samples with A260/280 between 1.8–2.1 were used for cDNA synthesis.

2.3. qPCR

cDNA was synthesized using the Qiagen QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen, Québec City, QC, Canada) according to manufacturers protocols. The concentration of the cDNA was measured using Nanodrop 1000 spectrophotometer and was normalized to 100 ng/µL. 200 nanogram of cDNA per well was used for qPCR. was TaqMan probes (Supplementary Table S1, Thermo Fisher, Mississauga, ON, Canada) and Thermo Fisher’s TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (#4444557, Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used for RT-PCR to determine gene expression using Quant Studio 3 RT-PCR instrument (Thermo Fisher, Mississauga, ON, Canada). Plate set up incorporated a randomized design, in order to reduce plate bias. The samples were therefore distributed across 2, 96-well plates, for each brain section, with 3 time points per plate. PCR conditions were followed according to manufacturer’s recommendations (TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix user guide Publication Number MAN0025706, Revision A.0) The 10 Heterozygote (het; Hexb−/+) and 10 knockout (KO) samples were randomized across the plates; therefore, there were 5 het and 5 KO samples per plate. The samples were pipetted using an electronic multichannel pipette in triplicate.

2.4. Protein Functional Association Network Analysis

STRING database (Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license) was used for predicting functional associations between proteins [17]. Briefly, this database integrates all known and predicted associations between proteins. Both physical and functional associations are considered in the networks. Single protein name of one of the tested genes (Hexb, Wfdc17, Ccl3, Lyz2, Fa2h, Mog or Ugt8a) was searched in STRING database. Organism ‘Mus musculus’ was chosen from the list. Then, the database summarized the network of predicted associations for the searched protein. Functional protein annotations from STRING database are assembled in the tables.

2.5. Data Analysis and Statistics

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) data analysis was done based on the Taylor et al. [18] and MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines. Briefly, Mean Ct (threshold cycle) of three technical replicates for each target was calculated. B-Actin was used as the reference gene. Brain (cerebral cortex or cerebellum) samples from 5-weeks old Hexb−/+ (Hexb-het) mice were considered control group. Average Ct for each target in the control group was calculated. The relative difference (deltaCt) between the average Ct for the control group and the mean Ct per individual sample within each target was determined. Relative quantity (fold change) was calculated using deltaCt i.e 2deltaCt. Then, normalized expression was determined by dividing relative quantity of target gene by the relative quantity of the reference gene. Statistical data analysis and graph plots were made using GraphPad Prism version 9.3.1 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA.

3. Results

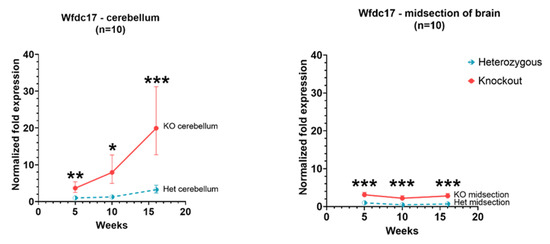

3.1. Wfdc17

In Hexb-KO cerebellum and cerebral cortex, the expression of Wfdc17 was significantly higher (p value < 0.05) than in Hexb-het mice. The pattern of expression differed between the cerebellum and cerebral cortex. In the cerebellum, Wfdc17 expression increased with age. However, in the Hexb-KO cerebral cortex the expression remained relatively unchanged with age, albeit levels were higher in Hexb-KO as compared to Hexb-het cohort (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Relative Wfdc17 expression in the cerebellum and cerebral cortex of Hexb-KO Sandhoff disease mouse model (*—p value < 0.05; **—p value < 0.01; ***—p value < 0.001; midsection of brain represents cerebral cortex).

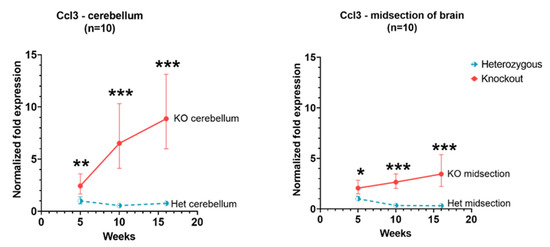

3.2. Ccl3

Ccl3 expression in Hexb-KO cerebellum and cerebral cortex remained higher than in Hexb-het at 5, 10 and 16 weeks of age (p value < 0.05). Moreover, there was a tendency of increase in Ccl3 expression in both cerebellum and cerebral cortex of Hexb-KO mice with age. The slope of rise in Ccl3 expression between 5 to 16 weeks was higher in cerebellum, as compared to the cerebral cortex, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Relative Ccl3 expression in the cerebellum and cerebral cortex of Hexb-KO Sandhoff disease mouse model (*—p value < 0.05; **—p value < 0.01; ***—p value < 0.001; midsection of brain represents cerebral cortex).

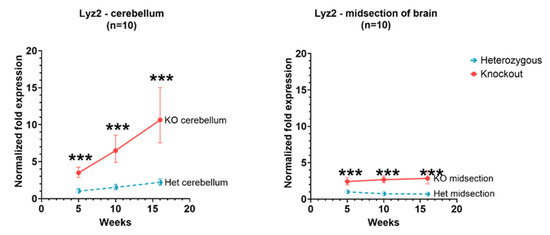

3.3. Lyz2

Expression of Lyz2 in the cerebellum and cerebral cortex showed a similar pattern as of Wfdc17 in Hexb-KO and Hexb-het mice. In Hexb-KO cerebellum and cerebral cortex, the expression of Lyz2 was significantly higher (p value < 0.05) than in Hexb-het mice. In the cerebral cortex, there was not a drastic change in the expression of Lyz2 with age; however, in the cerebellum, Lyz2 expression showed a rising trend with age. At 16 weeks of age, in Hexb-KO cerebellum, the Lyz2 expression was 3.2 times relative to 5-weeks expression. In the cerebellum of Hexb-het mice, there was a slight rising trend of Lyz2 expression between 5 to 16 weeks, while in the cerebellum of Hexb-KO mice there was a steeply rising trend of Lyz2 gene expression (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Relative Lyz2 expression in the cerebellum and cerebral cortex of Hexb-KO Sandhoff disease mouse model (***—p value < 0.001; midsection of brain represents cerebral cortex).

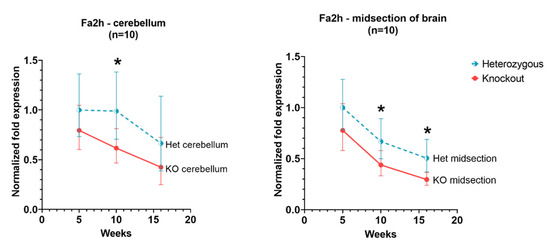

3.4. Fa2h

In the cerebellum and cerebral cortex, Fa2h expression levels in Hexb-KO were slightly lower than in Hexb-het for all ages. However, these levels were significant only at 10 weeks in the cerebellum and 10 weeks and 16 weeks in the cerebral cortex.

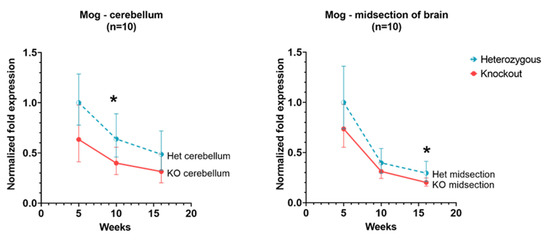

3.5. Mog

In the cerebellum, there was a downward trend in expression in Hexb-het and Hexb-KO mice. The analogous tendency of Mog expression is detectable in the cerebral cortex as well (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Relative Mog expression in the cerebellum and cerebral cortex of Hexb-KO Sandhoff disease mouse model (*—p value < 0.05; midsection of brain represents cerebral cortex).

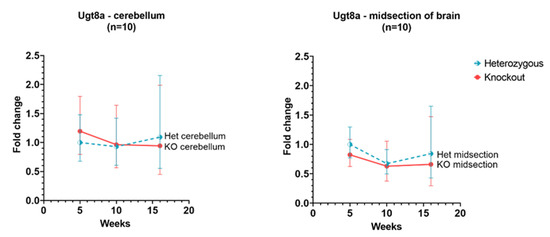

3.6. Ugt8a

In Hexb-KO cerebellum and cerebral cortex, Ugt8a gene showed a similar level of expression as in Hexb-het and the expression remained relatively unchanged between 5 to 16 weeks age for this gene, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Relative Ugt8a expression in the cerebellum and cerebral cortex of Hexb-KO Sandhoff disease mouse model (midsection of brain represents cerebral cortex).

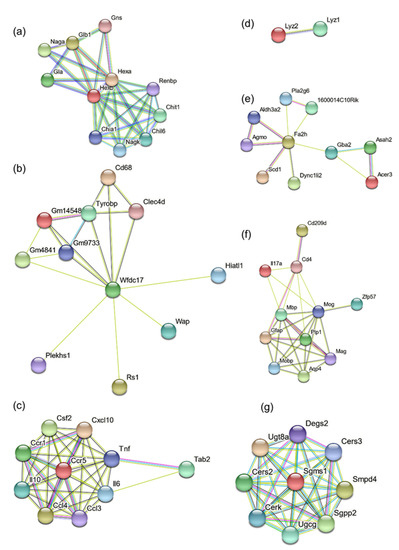

3.7. Protein Association Network Analysis

Further, we performed protein association network analysis using a string database for Hexb, Wfdc17, Ccl3, Lyz2, Fa2h, Mog and Ugt8a (Figure 6). In Figure 6a, Hexb is predicted to have a functional association with several genes, namely, Hexa, Gns, Glb1, Naga, Gla, Renbp, Chit1, Chil6, Nagk and Chia1. Most genes of the Hexb network are involved in the degradation of GM2 gangliosides and chitin (Table 2).

Figure 6.

Functional protein association network clusters for (a) Hexb, (b) Wfdc17, (c) CCl3, (d) Lyz2, (e) Fa2h, (f) Mog, and (g) Ugt8a.

Table 2.

Functional annotation of HexB protein association network.

For Wfdc17 functional association network (Figure 6b), most genes are associated with the immune system related pathways, with functions related to antigen uptake and cell–cell interaction, in macrophages, microglia and neutrophils (Figure 6b, Table 3).

Table 3.

Functional annotation of Wfdc17 protein association network.

Ccl3 is a chemokine and has inflammatory and chemokinetic characteristics. Its protein association network (Figure 6c, Table 4), primarily consists of other chemokine receptors, interleukins, GM-CSF (granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor) and tumor necrosis factor. This immune system activation was likely the result of gangliosides accumulation.

Table 4.

Functional annotation of Ccl3 protein association network.

Lyz2 was found to be associated with Lyz1. Their activity is primarily associated with monocyte-macrophage system. Fa2h protein is primarily responsible for fatty acid hydroxylation and generating hydroxylated sphingolipids (Figure 6d, Table 5). Fa2h protein association network (Figure 6e, Table 6) consists of unsaturated fatty acids generation, lipid synthesis, glucosylceramide catalysis, intracellular vesicle mobility (Dync1li2) and apoptosis (Pla2g6).

Table 5.

Functional annotation of Lyz2 protein association network.

Table 6.

Functional annotation of Fa2h protein association network.

The protein association network of Mog (Figure 6f, Table 7) consists of proteins involved in maternal and paternal gene imprinting (by DNA methylation and other epigenetic modifications; Zfp57), CNS osmoregulation (Aquaporin-4), interleukin, immune system associated receptors and co-receptors (Cd209d, Cd4) and other myelin-associated proteins.

Table 7.

Functional annotation of Mog protein association network.

The protein association network of Ugt8a consists of Cers3, Smpd4, Sgpp2, Ugcg, Cerk, Sgms1, Cers2 and Degs2 (Figure 6g, Table 8). Most of these genes are associated with cerebrosides and sphingosines metabolism.

Table 8.

Functional annotation of Ugt8a protein association network.

4. Discussion

SD and TSD are fatal neurodegenerative diseases that result from the build-up of GM2 Gangliosides in the lysosomes of neurons. The molecular changes occurring in GM2 Gangliosidosis are still not well understood [13,14]. In this study, we studied the expression of selected genes responsible for inflammation and myelination (Wfdc17, Ccl3, Lyz2, Fa2h, Mog and Ugt8a) for an improved understanding of the disease process. Wfdc17, Ccl3 and Lyz2 are primarily associated with immune system-related pathways, while Fa2h, Mog and Ugt8a are associated with myelination. Microglial activation, inflammation and associated demyelination are known causative factors for this disease and the genes for inflammation and demyelination have been found to be differentially regulated in the asymptomatic phase of the SD mouse model [16,19]. However, the temporal relationship of molecular mechanisms which lead to the development of symptoms is unclear. Therefore, in this study, we measured the expression of genes at early (5 weeks), intermediate (10 weeks) and late phase (16 weeks) of the disease in an attempt to establish temporal changes in expression of certain genes.

We found that immune system related genes (Wfdc17, Ccl3, Lyz2) are significantly upregulated, by several fold, at all ages in Hexb-KO mice relative to Hexb-het mice, while the difference in the expression levels of myelination related genes are not statistically significant. This suggests that the primary cause of pathology lies within immune system related genes. Moreover, the immune related gene expression changes are more pronounced in cerebellum as compared to the cerebral cortex. The levels of myelination-associated genes appear to have a lower expression trend in Hexb-KO mice, as compared to Hexb-het mice, however, this difference is not statistically significant in our study.

Microglia are the resident macrophages of the brain [20]. In the disease state, microglia respond to infections, disease, and injury in their primary role of phagocytosis and cytokine secretion. However, over time, rather than mitigating neuronal damage, they precipitate an inflammatory response. Pro-inflammatory cytokines released by microglia lead to further microglial activation, creating a positive feedback loop. This loss of “checkpoints” in neuroinflammatory pathways leads to a sustained inflammatory response and eventually neurodegeneration [21,22]. Microglial activation has been shown to precede neuronal death in SD mice, driven by lipid storage-induced microglia activation [13]. It has also been shown that lipid storage seen in GM2 Gangliosidosis may impair phagocytosis, leading to the extended release of toxins by microglia; whilst the phagocytosis of apoptotic neurons may actually be a trigger for pathogenesis [23]. The GM2 and other gangliosides accumulation triggers autoimmune responses, likely, through the interaction with Fcr-γ [16].

Ccl3, also termed macrophage inflammatory protein 1 α (MIP-1-α) is a chemokine that is produced endogenously by microglia, mediating an inflammatory response; a key feature of GM2 Ganglioside pathogenesis [24,25,26]. Davetelis and colleagues 2004, showed that when this gene is knocked out in SD mice, the disease is ameliorated [21]. Chemokines are thought to activate the NF-kappa B transcription factor, which itself regulates chemokines, creating a positive feedback loop, seen in autoimmune inflammation [27,28]. Ccl3 expression increases with the severity of the disease in Hexb-KO mouse models.

Lyz2 (also known as Lyz M) expression has also increased in the Hexb-KO cohort compared to the Hexb-het cohort at each time point, within a midsection of the brain as well as in the cerebellum. An early study into Lyz2, by Cross and colleagues (1998), characterized the Lyz2 gene and showed that Lyz2 is expressed in a tissue-dependent manner and has different expression profiles according to cell type, suggesting that Lyz2 is a potential marker of macrophages [29,30]. Lyz2 murine models have also been used to study the different populations of innate immune cells, in order to help understand disease progression, such as in multiple sclerosis, and the effect of immune cell response in its absence, highlighting their significance as a marker of microglial activation [31,32]. Expression of Lyz2 shows a slight downward trend in the cerebral cortex for Hexb-hets, while in the cerebellum, the expression has a slight upward slope (Figure 3). Microglia, in their homeostatic role, are thought to support myelinogenesis in the developmental brain (pre- and postnatally) [33,34]; they are also thought to continue to support the oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) in the adult brain [35]. This increase, therefore, may be considered to reflect patterns of myelination.

The Wfdc17 gene, a WAP domain protein, also known as activated microglia/macrophage WAP domain protein (AMWAP), has been shown to be active at the earliest stages of microglial activation, reducing transcripts of pro-inflammatory markers, whilst resulting in upregulation of other microglial markers. It is thought to not only counteract the inflammatory response, but also promote a homeostatic microglial response, as well as reducing neurotoxicity [36,37]. The relative gene expression levels for Wfdc17 in the cerebellum increase with age in Hexb-KO, as compared to Hexb-het mice, while in the cerebral cortex the expression levels remain largely unchanged. Hexb-KO cerebellum and cerebral cortex show higher levels than in Hexb-het, but relative levels are lower in the cerebral cortex. A similar expression pattern is visible with Lyz2 as well. Lyz2 and Wfdc17 are both thought to be regulated by transcription factor NF-kappa B [28]. NF-kappa B is induced by Ccl3, suggesting that Wdfc17 and Lyz2 increase following microglial activation after Ccl3 release. The increased expression of Ccl3 as a marker of microglial activation, Lyz2 as an inflammatory marker, and Wdfc17 as a marker of anti-inflammatory response suggests that from 5-weeks, there is microglial activation and an inflammatory response occurring in both the cerebral cortex and the cerebellum. These genes are all thought to be mediated by the NF-kappa B transcription factor, which itself is induced by Ccl3, regulating chemokines in a positive feedback loop.

Among the genes related to myelination—Ugt8A, Fa2h and Mog, our data show that in both Hexb-KO and Hexb-het cerebral cortex and cerebellum, Fa2h and Mog have a downward trend of expression with age, while Ugt8a does not change significantly with age. Mog and Fa2h expression are consistently lower in Hexb-KOs, compared to Hexb-hets, the difference is significant at 10-weeks or 12-weeks of age in the cerebral cortex and cerebellum (Figure 4 and Figure 7). For Mog and Fa2h, it appears that the lack of statistical significance is due to the limited number of mice used in this study.

Figure 7.

Relative Fa2h expression in the cerebellum and cerebral cortex of Hexb-KO Sandhoff disease mouse model (*—p value < 0.05; midsection of brain represents cerebral cortex).

There is not a significant change between the levels of Ugt8a in the cerebral cortex and cerebellum at any age (Figure 5). The Ugt8a gene (UDP Galactosyltransferase 8), also known as UDP-galactose: ceramide galactosyltransferase, and commonly referred to as the CGT gene [38]. However, a murine model deficient in Ugt8a, showed impaired axon insulation resulting in body tremors and loss of motor activity. This phenotype is similar to that seen in SD mice [39].

The Fa2h gene codes for fatty acid 2-hydroxylase (also known as fatty acid-α-hydroxylase). The expression of Fa2h in Hexb-KOs remains lower than Hexb-hets, however, the difference is not statistically significant. There is also a downward trend of Fa2h expression with age. Fatty acid 2-hydroxylase catalyzes fatty acid 2-hydroxylation, synthesizing 2-hydroxy-fatty acids. These fatty acids are reported to be an important component of viable myelin, the absence of which can result in demyelination [40]. Expression of Fa2h shows a downward trend in the cerebral cortex and the cerebellum (Figure 7).

Mog, or Myelin-Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein is a minor glycoprotein found on the external lamellae of myelin sheaths and on the surface of myelinating oligodendrocytes. Due to the “external location” of the Mog protein in the myelin sheath and the fact that it occurs in the later stages of myelination, it is thought to be important for myelination completion and maintenance [41]. Its location on the surface of myelin sheath makes it a target for antibodies in autoimmune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis [42,43]. The expression of the Mog gene in the cerebral cortex and cerebellum of Hexb-hets remains higher than in Hexb-KOs, however, the difference is not statistically significant (Figure 4), similar to the pattern of the Ugt8a gene and the Fa2h genes. This aligns with the previous studies of Mog expression which suggest that following higher expression a few days after birth, the Mog expression is maintained at a lower level for myelin maintenance [41,43].

Gene expression related to demyelination, including genes Ugt8a, Fa2h and Mog, show a general lower level in the Hexb-KOs, compared to the Hexb-hets. Though, the trend does not appear to be statistically significant, probably due to the lower number of mice used in this study. However, since the levels are lower in KO as compared to the heterozygotes at each time point analyzed, it indicates that other mechanisms associated with inflammatory pathways might also be playing a role. The Ugt8a and Fa2h have been shown to be vital genes in the formation of galactosylceramides, an important component of myelin [40]. Without them, viable myelin is not synthesized. Mog is also a recognized marker of myelination [44].

Further examination of functional protein networks (Figure 6) has revealed the involvement of other downstream or upstream genes and has shed some light regarding the pathway which might get affected by these interactions. Future experiments will be needed to outline the specific pathways that possibly affect myelination. Current evidence from this study indicates an overwhelming activation of inflammatory pathways; however, the extent of demyelination in the disease process remains unclear.

This study has the limitation of analyzing the restricted number of genes by qPCR. However, we demonstrate that there is an age-dependent significant increase in expression of microglial/inflammatory genes, from 5-weeks to the near humane end-point, i.e., 16-week time point. While the expression of those genes involved in myelination decreases slightly or remains unchanged. In conformance to the previous knowledge of cerebellum pathology, the inflammatory gene expression was found more pronounced in the cerebellum, as compared to the cerebral cortex. This information lays the foundation for future studies which shall target exhaustive, high-throughput gene expression modalities (such as 10X genomics). This will delineate the gene expression changes at different ages to determine expression of genes in specific neuronal cell types and thus further extensively investigate the mechanisms and effects of these inflammatory reactions within the SD brain. Such knowledge will pave the way for better understanding of molecular pathophysiology and may guide rational and precise therapeutic modalities.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/genes13112020/s1, Table S1: Genomic locations and context sequences of qPCR TaqMan probes.

Author Contributions

K.S. and J.S.W. wrote the manuscript. K.S., B.M.Q., M.M. and Z.C. analyzed the data and/or conducted the experiments. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by Cure Tay-Sachs Foundation (CTSF-361124).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All experiments were performed in accordance with Queen’s University Animal Care Committee (2017-1707).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The information regarding the context sequence of probes used in this study is available in Table S1, in Supplementary Materials section of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Andrew Winterborn, Queen’s University for the discussions and knowledge towards animal care/handling.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sandhoff, K.; Harzer, K. Gangliosides and gangliosidoses: Principles of molecular and metabolic pathogenesis. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 10195–10208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandhoff, K. My Journey into the World of Sphingolipids and Sphingolipidoses. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2012, 88, 554–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.A. Characterization of Two HEXB Gene Mutations in Argentinean Patients with Sandhoff Disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1992, 1180, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemieux, M.J.; Mark, B.L.; Cherney, M.M.; Withers, S.G.; Mahuran, D.J.; James, M.N.G. Crystallographic Structure of Human β-Hexosaminidase A: Interpretation of Tay-Sachs Mutations and Loss of GM2 Ganglioside Hydrolysis. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 359, 913–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gravel, R.A.; Triggs-Raine, B.L.; Mahuran, D.J. Biochemistry and genetics of Tay-Sachs disease. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 1991, 18, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyakumar, M. Glycosphingolipid Lysosomal Storage Diseases: Therapy and Pathogenesis. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2002, 28, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachon-Gonzalez, M.B.; Zaccariotto, E.; Cox, T.M. Genetics and Therapies for GM2 Gangliosidosis. Curr. Gene Ther. 2018, 18, 68–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, D.; Akeboshi, H.; Matsuoka, K.; Yasuoka, H.; Miyasaki, E.; Kasahara, Y.; Kawashima, I.; Chiba, Y.; Jigami, Y.; Taki, T.; et al. Highly Phosphomannosylated Enzyme Replacement Therapy for GM2 Gangliosidosis. Ann. Neurol. 2011, 69, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.; Nietupski, J.B.; Park, H.; Cao, J.; Bangari, D.S.; Silvescu, C.; Wilper, T.; Randall, K.; Tietz, D.; Wang, B.; et al. Substrate Reduction Therapy for Sandhoff Disease through Inhibition of Glucosylceramide Synthase Activity. Mol. Ther. 2019, 27, 1495–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmon, K.J.; Thompson, P.; Woodley, E.; Karumuthil-Melethil, S.; Heindel, C.; Keimel, J.G.; Kaemmerer, W.F.; Gray, S.J.; Walia, J.S. Treatment of GM2 Gangliosidosis in Adult Sandhoff Mice Using an Intravenous Self-Complementary Hexosaminidase Vector. Curr. Gene Ther. 2022, 22, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaimardanova, A.A.; Chulpanova, D.S.; Solovyeva, V.V.; Aimaletdinov, A.M.; Rizvanov, A.A. Functionality of a Bicistronic Construction Containing HEXA and HEXB Genes Encoding β-Hexosaminidase A for Cell-Mediated Therapy of GM2 Gangliosidoses. Neural Regen. Res. 2021, 17, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray-Edwards, H.L.; Randle, A.N.; Maitland, S.A.; Benatti, H.R.; Hubbard, S.M.; Canning, P.F.; Vogel, M.B.; Brunson, B.L.; Hwang, M.; Ellis, L.E.; et al. Adeno-Associated Virus Gene Therapy in a Sheep Model of Tay-Sachs Disease. Hum. Gene Ther. 2018, 29, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, R.; Tifft, C.J.; Proia, R.L. Microglial Activation Precedes Acute Neurodegeneration in Sandhoff Disease and Is Suppressed by Bone Marrow Transplantation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 10954–10959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myerowitz, R. Molecular Pathophysiology in Tay-Sachs and Sandhoff Diseases as Revealed by Gene Expression Profiling. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002, 11, 1343–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Futerman, A.H.; Meer, G. The Cell Biology of Lysosomal Storage Disorders. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 5, 554–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, Y. Improvement in Dysmyelination by the Inhibition of Microglial Activation in a Mouse Model of Sandhoff Disease. Neuroreport 2018, 29, 962–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Nastou, K.C.; Lyon, D.; Kirsch, R.; Pyysalo, S.; Doncheva, N.T.; Legeay, M.; Fang, T.; Bork, P.; et al. The STRING Database in 2021: Customizable Protein-Protein Networks, and Functional Characterization of User-Uploaded Gene/Measurement Sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D605–D612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.C.; Nadeau, K.; Abbasi, M.; Lachance, C.; Nguyen, M.; Fenrich, J. The Ultimate QPCR Experiment: Producing Publication Quality, Reproducible Data the First Time. Trends Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, Y. FcRγ-Dependent Immune Activation Initiates Astrogliosis during the Asymptomatic Phase of Sandhoff Disease Model Mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greter, M.; Lelios, I.; Croxford, A.L. Microglia Versus Myeloid Cell Nomenclature during Brain Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, S. Microglia in neurodegeneration. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 1359–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, G.C.; Vilalta, A. How microglia kill neurons. Brain Res. 2015, 1628, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeyakumar, M. Central Nervous System Inflammation Is a Hallmark of Pathogenesis in Mouse Models of GM1 and GM2 Gangliosidosis. Brain 2003, 126, 974–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davatelis, G. Cloning and Characterization of a CDNA for Murine Macrophage Inflammatory Protein (MIP), a Novel Monokine with Inflammatory and Chemokinetic Properties. J. Exp. Med. 1988, 167, 1939–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, M.; Stebut, E. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2004, 36, 1882–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolpe, S.D.; Cerami, A. Macrophage Inflammatory Proteins 1 and 2: Members of a Novel Superfamily of Cytokines. FASEB J. 1989, 3, 2565–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.P.; Proia, R.L. Deletion of Macrophage-Inflammatory Protein 1 Alpha Retards Neurodegeneration in Sandhoff Disease Mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 8425–8430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellrichmann, G. Constitutive Activity of NF-Kappa B in Myeloid Cells Drives Pathogenicity of Monocytes and Macrophages during Autoimmune Neuroinflammation. J. Neuroinflamm. 2012, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, M. Mouse Lysozyme M Gene: Isolation, Characterization, and Expression Studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1988, 85, 6232–6236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieghofer, P.; Prinz, M. Genetic Manipulation of Microglia during Brain Development and Disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1862, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caravagna, C. Diversity of innate immune cell subsets across spatial and temporal scales in an EAE mouse model. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragland, S.A.; Criss, A.K. From Bacterial Killing to Immune Modulation: Recent Insights into the Functions of Lysozyme. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, 1006512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paolicelli, R.C. Synaptic Pruning by Microglia Is Necessary for Normal Brain Development. Science 2011, 333, 1456–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, K.M.; Nelson, L.H. Microglia and Beyond: Innate Immune Cells As Regulators of Brain Development and Behavioral Function. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanisch, U.K.; Kettenmann, H. Microglia: Active Sensor and Versatile Effector Cells in the Normal and Pathologic Brain. Nat. Neurosci. 2007, 10, 1387–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlstetter, M. The Novel Activated Microglia/Macrophage WAP Domain Protein, AMWAP, Acts as a Counter-Regulator of Proinflammatory Response. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 3379–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslanidis, A. Activated Microglia/Macrophage Whey Acidic Protein (AMWAP) Inhibits NFκB Signaling and Induces a Neuroprotective Phenotype in Microglia. J. Neuroinflam. 2015, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meech, R. The UDP-Glycosyltransferase (UGT) Superfamily: New Members, New Functions, and Novel Paradigms. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1153–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosio, A.; Binczek, E.; Stoffel, W. Functional Breakdown of the Lipid Bilayer of the Myelin Membrane in Central and Peripheral Nervous System by Disrupted Galactocerebroside Synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 13280–13285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, E.N.; Alderson, N.L.; Monje, P.V.; Wood, P.M.; Hama, H. FA2H Is Responsible for the Formation of 2-Hydroxy Galactolipids in Peripheral Nervous System Myelin. J. Lipid. Res. 2008, 49, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham-Dinh, D. Myelin/Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Is a Member of a Subset of the Immunoglobulin Superfamily Encoded within the Major Histocompatibility Complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 7990–7994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linington, C. Augmentation of Demyelination in Rat Acute Allergic Encephalomyelitis by Circulating Mouse Monoclonal Antibodies Directed against a Myelin/Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein. Am. J. Pathol. 1988, 130, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peschl, P. Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein: Deciphering a Target in Inflammatory Demyelinating Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosius, W.; Michalak, S.; Kozubski, W.; Kalinowska, A. Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Associated Disease: Current Insights into the Disease Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).