Frameshift Variant in MFSD12 Explains the Mushroom Coat Color Dilution in Shetland Ponies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

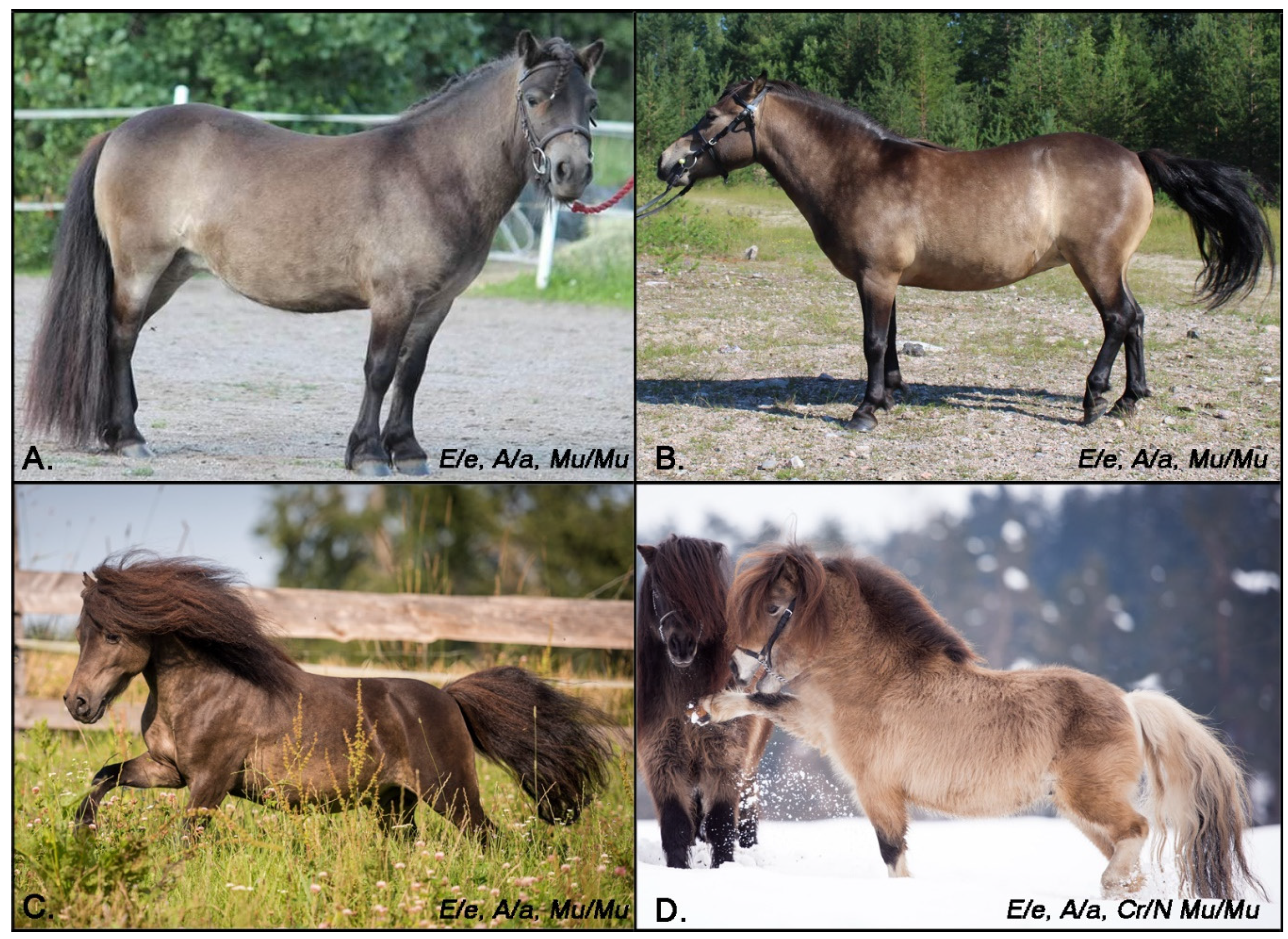

2.1. Horses and Phenotyping

2.2. Genome Wide Association Study

2.3. Validation of Association

2.4. Whole Genome Sequencing and Variant Investigation

2.5. Validation of Causative Variant

2.6. Ophthalmic Examination

2.7. Data Availability

3. Results

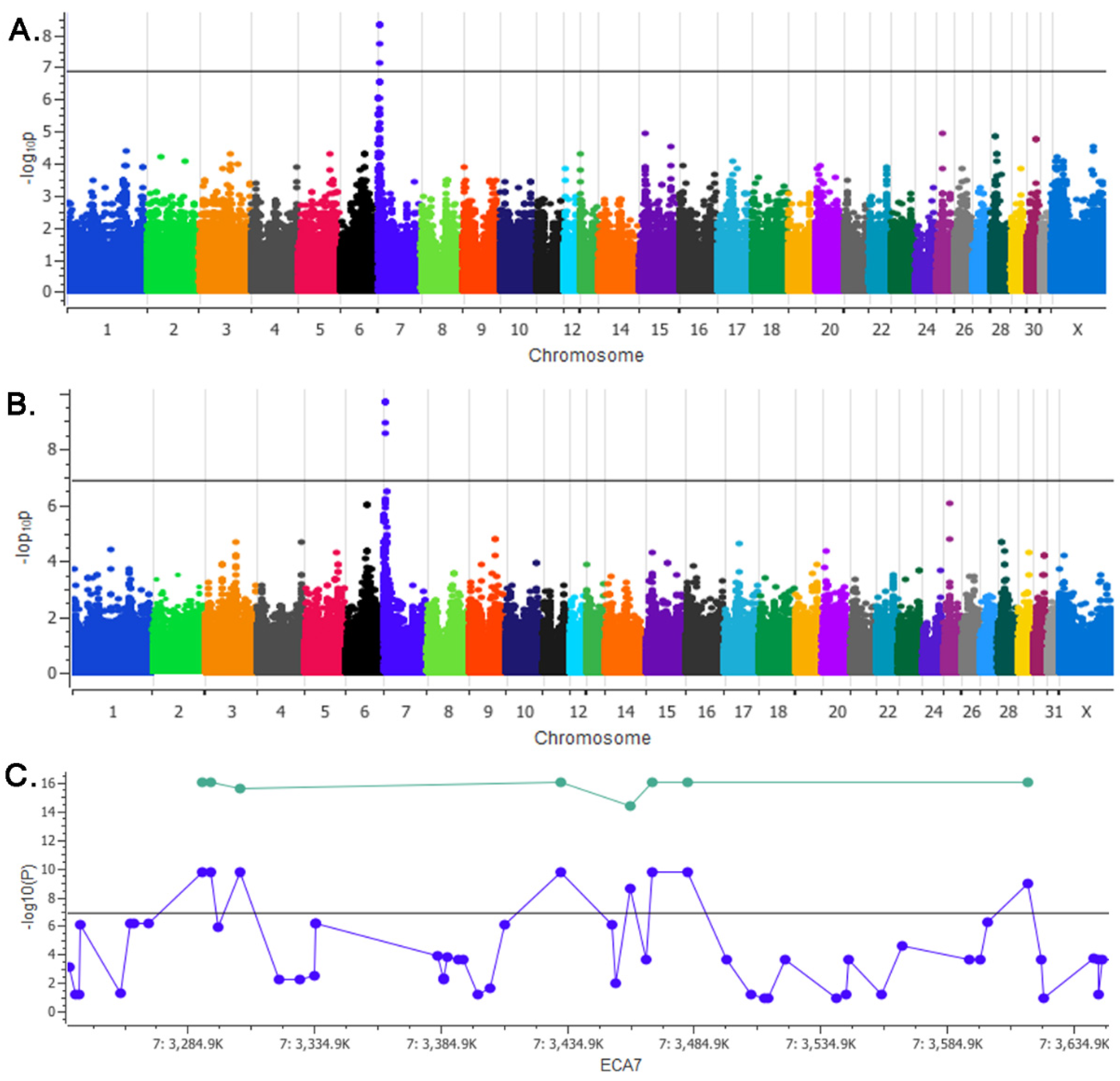

3.1. GWAS

3.2. Ophthalmic Examination

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baxter, L.L.; Watkins-Chow, D.E.; Pavan, W.J.; Loftus, S.K. A curated gene list for expanding the horizons of pigmentation biology. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2019, 32, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieder, S.; Taourit, S.; Mariat, D.; Langlois, B.; Guerin, G. Mutations in the agouti (ASIP), the extension (MC1R), and the brown (TYRP1) loci and their association to coat color phenotypes in horses (Equus caballus). Mamm. Genome 2001, 12, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariat, D.; Taourit, S.; Guerin, G. A mutation in the MATP gene causes the cream coat colour in the horse. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2003, 35, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevane, N.; Sanz, C.R.; Dunner, S. Explicit evidence for a missense mutation in exon 4 of SLC45A2 gene causing the pearl coat dilution in horses. Anim. Genet. 2019, 50, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holl, H.M.; Pflug, K.M.; Yates, K.M.; Hoefs-Martin, K.; Shepard, C.; Cook, D.G.; Lafayette, C.; Brooks, S.A. A candidate gene approach identifies variants in SLC45A2 that explain dilute phenotypes, pearl and sunshine, in compound heterozygote horses. Anim. Genet. 2019, 50, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.; Brooks, S.; Bellone, R.; Bailey, E. Missense mutation in exon 2 of SLC36A1 responsible for champagne dilution in horses. PLoS Genet. 2008, 4, e1000195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imsland, F.; McGowan, K.; Rubin, C.J.; Henegar, C.; Sundstrom, E.; Berglund, J.; Schwochow, D.; Gustafson, U.; Imsland, P.; Lindblad-Toh, K.; et al. Regulatory mutations in TBX3 disrupt asymmetric hair pigmentation that underlies Dun camouflage color in horses. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunberg, E.; Andersson, L.; Cothran, G.; Sandberg, K.; Mikko, S.; Lindgren, G. A missense mutation in PMEL17 is associated with the Silver coat color in the horse. BMC Genet. 2006, 7, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L.S.; Wilbe, M.; Viluma, A.; Cothran, G.; Ekesten, B.; Ewart, S.; Lindgren, G. Equine multiple congenital ocular anomalies and silver coat colour result from the pleiotropic effects of mutant PMEL. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sponenberg, D.P. Equine Color Genetics, 3rd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; p. 255. [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen, A.G. Genetic Testing of Silver Shetland Ponies for Allelic Variants of MC1R, ASIP and PMEL17. Master’s Thesis, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, J.L.; Mickelson, J.R.; Cothran, E.G.; Andersson, L.S.; Axelsson, J.; Bailey, E.; Bannasch, D.; Binns, M.M.; Borges, A.S.; Brama, P.; et al. Genetic diversity in the modern horse illustrated from genome-wide SNP data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, M.; Kowalski, E.; Grahn, R.; Bras, D.; Penedo, M.C.T.; Bellone, R. Two Variants in SLC24A5 are associated with “Tiger-Eye” iris pigmentation in puerto rican paso fino horses. G3 (Bethesda) 2017, 7, 2799–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locke, M.M.; Penedo, M.C.; Bricker, S.J.; Millon, L.V.; Murray, J.D. Linkage of the grey coat colour locus to microsatellites on horse chromosome 25. Anim. Genet. 2002, 33, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellone, R.R.; Liu, J.Y.; Petersen, J.L.; Mack, M.; Singer-Berk, M.; Drogemuller, C.; Malvick, J.; Wallner, B.; Brem, G.; Penedo, M.C.; et al. A missense mutation in damage-specific DNA binding protein 2 is a genetic risk factor for limbal squamous cell carcinoma in horses. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schaefer, R.J.; Schubert, M.; Bailey, E.; Bannasch, D.L.; Barrey, E.; Bar-Gal, G.K.; Brem, G.; Brooks, S.A.; Distl, O.; Fries, R.; et al. Developing a 670k genotyping array to tag ~2M SNPs across 24 horse breeds. BMC Genomics 2017, 18, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeson, S.K.; Schaefer, R.J.; Mason, V.C.; McCue, M.E. Robust remapping of equine SNP array coordinates to EquCab3. Anim. Genet. 2019, 50, 114–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalbfleisch, T.S.; Rice, E.S.; DePriest, M.S., Jr.; Walenz, B.P.; Hestand, M.S.; Vermeesch, J.R.; O’Connell, B.L.; Fiddes, I.T.; Vershinina, A.O.; Saremi, N.F.; et al. Improved reference genome for the domestic horse increases assembly contiguity and composition. Commun. Biol. 2018, 1, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagannathan, V.; Gerber, V.; Rieder, S.; Tetens, J.; Thaller, G.; Drogemuller, C.; Leeb, T. Comprehensive characterization of horse genome variation by whole-genome sequencing of 88 horses. Anim. Genet. 2019, 50, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.; Layer, R.M.; Faust, G.G.; Lindberg, M.R.; Rose, D.B.; Garrison, E.P.; Marth, G.T.; Quinlan, A.R.; Hall, I.M. SpeedSeq: Ultra-fast personal genome analysis and interpretation. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 966–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faust, G.G.; Hall, I.M. SAMBLASTER: Fast duplicate marking and structural variant read extraction. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2503–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, A.; Vilella, A.J.; Cuppen, E.; Nijman, I.J.; Prins, P. Sambamba: Fast processing of NGS alignment formats. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 2032–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenna, A.; Hanna, M.; Banks, E.; Sivachenko, A.; Cibulskis, K.; Kernytsky, A.; Garimella, K.; Altshuler, D.; Gabriel, S.; Daly, M.; et al. The genome analysis toolkit: A MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cingolani, P.; Platts, A.; Wang le, L.; Coon, M.; Nguyen, T.; Wang, L.; Land, S.J.; Lu, X.; Ruden, D.M. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly (Austin) 2012, 6, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Untergasser, A.; Cutcutache, I.; Koressaar, T.; Ye, J.; Faircloth, B.C.; Remm, M.; Rozen, S.G. Primer3-new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koressaar, T.; Remm, M. Enhancements and modifications of primer design program Primer3. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 1289–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ye, J.; Coulouris, G.; Zaretskaya, I.; Cutcutache, I.; Rozen, S.; Madden, T.L. Primer-BLAST: A tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinformatics 2012, 13, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.A.; Lear, T.L.; Adelson, D.L.; Bailey, E. A chromosome inversion near the KIT gene and the Tobiano spotting pattern in horses. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2007, 119, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauswirth, R.; Haase, B.; Blatter, M.; Brooks, S.A.; Burger, D.; Drogemuller, C.; Gerber, V.; Henke, D.; Janda, J.; Jude, R.; et al. Mutations in MITF and PAX3 cause “splashed white” and other white spotting phenotypes in horses. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberth, J.E. Chondrodysplasia-Like Dwarfism in the Miniature Horse. Master’s Thesis, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, K.; Mendoza-Revilla, J.; Sohail, A.; Fuentes-Guajardo, M.; Lampert, J.; Chacon-Duque, J.C.; Hurtado, M.; Villegas, V.; Granja, V.; Acuna-Alonzo, V.; et al. A GWAS in Latin Americans highlights the convergent evolution of lighter skin pigmentation in Eurasia. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, N.G.; Kelly, D.E.; Hansen, M.E.B.; Beltrame, M.H.; Fan, S.; Bowman, S.L.; Jewett, E.; Ranciaro, A.; Thompson, S.; Lo, Y.; et al. Loci associated with skin pigmentation identified in African populations. Science 2017, 358, eaan8433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedan, B.; Cadieu, E.; Botherel, N.; Dufaure de Citres, C.; Letko, A.; Rimbault, M.; Drogemuller, C.; Jagannathan, V.; Derrien, T.; Schmutz, S.; et al. Identification of a missense variant in MFSD12 involved in dilution of Phaeomelanin leading to white or cream coat color in dogs. Genes 2019, 10, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellone, R.R.; Brooks, S.A.; Sandmeyer, L.; Murphy, B.A.; Forsyth, G.; Archer, S.; Bailey, E.; Grahn, B. Differential gene expression of TRPM1, the potential cause of congenital stationary night blindness and coat spotting patterns (LP) in the Appaloosa horse (Equus caballus). Genetics 2008, 179, 1861–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandmeyer, L.S.; Bellone, R.R.; Archer, S.; Bauer, B.S.; Nelson, J.; Forsyth, G.; Grahn, B.H. Congenital stationary night blindness is associated with the leopard complex in the miniature horse. Vet. Ophthalmol. 2012, 15, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, K.L.; Kaese, H.J.; Valberg, S.J.; Hendrickson, J.A.; Rendahl, A.K.; Bellone, R.R.; Dynes, K.M.; Wagner, M.L.; Lucio, M.A.; Cuomo, F.M.; et al. Genetic risk factors for insidious equine recurrent uveitis in Appaloosa horses. Anim. Genet. 2014, 45, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Location 1 | Variant ID | GWAS P-Value 2 | Pcombined-Value (genotype) 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| chr7:3290682 | rs68661375 | 2.08 × 10−10 | 9.84 × 10−17 |

| chr7:3293765 | rs395756529 | 2.08 × 10−10 | 9.84 × 10−17 |

| chr7:3305324 | rs395273754 | 2.08 × 10−10 | 2.71 × 10−16 |

| chr7:3431918 | rs1139100844 | 2.08 × 10−10 | 9.84 × 10−17 |

| chr7:3459389 | rs68664417 | 2.87 × 10−9 | 5.20 × 10−15 |

| chr7:3468232 | rs68664452 | 2.08 × 10−10 | 9.84 × 10−17 |

| chr7:3482185 | rs1148601322 | 2.08 × 10−10 | 9.84 × 10−17 |

| chr7:3616751 | rs394856954 | 1.16 × 10−9 | 9.84 × 10−17 |

| Breed/Phenotype | Homozygous Reference | Heterozygous | Homozygous Alternate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shetland (Mu)1 | 0 | 0 | 40 |

| Shetland (Ch)2 | 14 | 15 | 0 |

| Shetland/3 | 30 | 3 | 0 |

| Miniature Horse/4 | 24 | 4 | 1 |

| Icelandic Horse/4 | 19 | 8 | 2 |

| Quarter Horse/4 | 16 | 6 | 0 |

| Thoroughbred/4 | 16 | 8 | 0 |

| Genotype | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotype | N/N | N/Mu1 | Mu/Mu1 |

| Shetland (Mu) 2 | 0 | 0 | 45 |

| Shetland (Ch) 3 | 32 | 19 | 0 |

| X2 | P = 1.15 × 10−22 | ||

| Genotype | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breed | N/N | N/Mu | Mu/Mu | Sample Size | Frequency 3 |

| Shetland Pony 1 | 143 | 24 | 10 | 177 | 0.12 |

| Miniature Horse | 124 | 5 | 0 | 129 | 0.02 |

| Icelandic Horse | 29 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 0 |

| Belgian | 33 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 0 |

| Rocky Mtn Horse 2 | 59 | 0 | 0 | 59 | 0 |

| Friesian | 32 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 0 |

| Arabian | 35 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 0 |

| Quarter Horse | 32 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 0 |

| Thoroughbred | 31 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 0 |

| Non-Chestnut Mushroom Ponies | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | Agouti | Extension | Mushroom | Cream | Dun | Phenotype |

| Bay | A/a | E/e | Mu/Mu | N/N | nd2/nd2 | dilute bay |

| Bay | A/a | E/e | Mu/Mu | N/N | nd1/nd2 | dilute bay |

| Bay | A/a | E/e | Mu/Mu | N/N | nd2/nd2 | dilute bay |

| Bay | A/A | E/e | Mu/Mu | N/Cr | nd2/nd2 | buckskin dilute |

| Bay | A/A | E/e | Mu/Mu | N/N | nd2/nd2 | dilute bay |

| Bay | A/a | E/e | Mu/Mu | N/N | nd2/nd2 | dark dilute bay |

| Black | a/a | E/e | Mu/Mu | N/N | nd2/nd2 | black |

| Palomino | a/a | e/e | Mu/Mu | N/Cr | nd2/nd2 | mushroom |

| Palomino | a/a | e/e | Mu/Mu | N/Cr | nd2/nd2 | mushroom |

| Palomino | a/a | e/e | Mu/Mu | N/Cr | nd2/nd2 | mushroom |

| Palomino | A/a | e/e | Mu/Mu | N/Cr | nd2/nd2 | mushroom |

| Palomino | a/a | e/e | Mu/Mu | N/Cr | D/nd2 | dilute dunalino |

| Ophthalmic Findings | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | ASIP1 | MC1R2 | MFSD123 | SLC45A24 | KIT5 | MITF6 | Anterior 7 | Posterior 8 |

| 463 | a/a | e/e | Mu/Mu | N/Cr | N/To | N/S | OD hypo 11 | hypo 9 |

| 466 | a/a | e/e | Mu/Mu | N/N | N/To | N/N | hypo | pig 10 |

| 467 | a/a | e/e | Mu/Mu | N/Cr | N/N | N/N | hypo | pig |

| 477 | a/a | e/e | Mu/Mu | N/N | N/N | N/N | hyper | pig |

| 478 | A/a | e/e | Mu/Mu | N/N | N/N | N/N | hyper | pig |

| 479 | a/a | e/e | Mu/Mu | N/N | N/N | N/N | hypo | pig |

| 480 | a/a | e/e | Mu/Mu | N/N | N/To | N/N | pig | hypo |

| 481 | a/a | e/e | Mu/Mu | N/N | N/To | N/N | hypo | hypo |

| 483 | a/a | e/e | Mu/Mu | N/N | N/To | N/N | hypo | hypo |

| 464 | A/a | e/e | N/Mu | N/Cr | To/To | N/S | hypo | hypo |

| 465 | A/A | e/e | N/Mu | N/N | N/To | N/N | pig | pig |

| 468 | a/a | e/e | N/Mu | N/N | N/To | N/N | pig | hypo |

| 469 | a/a | e/e | N/Mu | N/N | N/To | N/N | pig | hypo |

| 470 | a/a | E/e | N/Mu | N/N | N/To | N/N | pig | hypo |

| 471 | a/a | E/e | N/N | N/N | N/N | N/N | pig | pig |

| 472 | A/a | e/e | N/N | N/N | N/To | N/N | pig | hypo |

| 473 | A/a | E/e | N/N | N/N | N/To | N/N | pig | hypo |

| 474 | a/a | e/e | N/Mu | N/N | N/To | N/N | hypo | pig |

| 475 | A/a | e/e | N/Mu | N/Cr | N/To | N/N | hypo | hypo |

| 476 | A/A | E/e | N/N | N/N | N/N | N/N | pig | pig |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tanaka, J.; Leeb, T.; Rushton, J.; Famula, T.R.; Mack, M.; Jagannathan, V.; Flury, C.; Bachmann, I.; Eberth, J.; McDonnell, S.M.; et al. Frameshift Variant in MFSD12 Explains the Mushroom Coat Color Dilution in Shetland Ponies. Genes 2019, 10, 826. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10100826

Tanaka J, Leeb T, Rushton J, Famula TR, Mack M, Jagannathan V, Flury C, Bachmann I, Eberth J, McDonnell SM, et al. Frameshift Variant in MFSD12 Explains the Mushroom Coat Color Dilution in Shetland Ponies. Genes. 2019; 10(10):826. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10100826

Chicago/Turabian StyleTanaka, Jocelyn, Tosso Leeb, James Rushton, Thomas R. Famula, Maura Mack, Vidhya Jagannathan, Christine Flury, Iris Bachmann, John Eberth, Sue M. McDonnell, and et al. 2019. "Frameshift Variant in MFSD12 Explains the Mushroom Coat Color Dilution in Shetland Ponies" Genes 10, no. 10: 826. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10100826

APA StyleTanaka, J., Leeb, T., Rushton, J., Famula, T. R., Mack, M., Jagannathan, V., Flury, C., Bachmann, I., Eberth, J., McDonnell, S. M., Penedo, M. C. T., & Bellone, R. R. (2019). Frameshift Variant in MFSD12 Explains the Mushroom Coat Color Dilution in Shetland Ponies. Genes, 10(10), 826. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10100826