Abstract

The retina is a part of the central nervous system, a thin multilayer with neuronal lamination, responsible for detecting, preprocessing, and sending visual information to the brain. Many retinal diseases are characterized by hemodynamic perturbations and neurodegeneration leading to vision loss and reduced quality of life. Since catecholamines and respective bindings sites have been characterized in the retina, we systematically reviewed the literature with regard to retinal expression, distribution and function of alpha1 (α1)-, alpha2 (α2)-, and beta (β)-adrenoceptors (ARs). Moreover, we discuss the role of the individual adrenoceptors as targets for the treatment of retinal diseases.

1. Introduction

Many ocular diseases, such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD), diabetic retinopathy, retinal vascular occlusion and glaucoma frequently cause severe visual impairment substantially diminishing the quality of life [1,2,3,4,5]. Permanent ischemia or ischemia-reperfusion injury of the retina and/or optic nerve have been implicated in the pathophysiology of these diseases [6,7,8,9]. Retinal ischemic conditions may lead to a direct loss of cellular function. However, they can also induce various secondary sequelae, such as retinal edema, hemorrhage, neovascularization, detachment and secondary glaucoma [10].

Since the retina is the tissue with the highest metabolic demand in the body, it is not surprising that retinal hemodynamic perturbations play a critical role in the pathogenesis of numerous ocular diseases [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. The retinal vascular structure provides metabolic support for neural and glial cells while minimizing interference with light-sensing [19]. In this context, modulation of vascular diameter by local mechanical and chemical stimuli can be considered the main basic regulatory mechanism in the retinal circulation [20,21].

Receptor families comprising multiple subtypes with organ-specific patterns of neurovascular expression and function appear to be attractive candidates for the development of targeted therapies against diseases associated with abnormal tissue perfusion. One such intriguing receptor family is the adrenoceptor (AR) family.

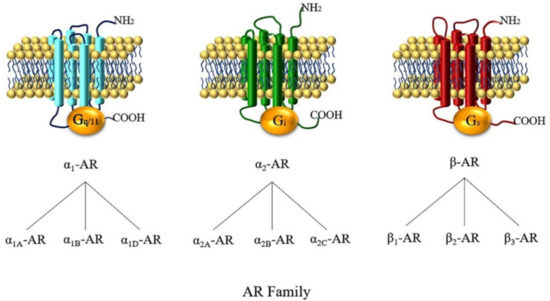

The discovery of ARs by Ahlquist more than six decades ago has uncovered the adrenergic signaling pathways as pivotal regulators of systemic arterial blood pressure and other metabolic and central nervous system functions [22]. ARs belong to the superfamily of guanosine triphosphate-binding protein (G protein)-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and are targets of catecholamines, especially epinephrine and noradrenaline [22,23,24,25]. According to its pharmacological properties, amino acid sequence, and signaling mechanisms, the AR family is subdivided into three subfamilies, the alpha1 (α1)-, alpha2 (α2)-, and the beta (β)-AR subfamily [26]. Each class is composed of three subtypes (α1A, α1B, α1D, α2A, α2B, α2C, β1, β2, and β3) (Figure 1) [27]. Members of the α1-AR subfamily are widely expressed throughout the cardiovascular system [28]. They critically participate in the regulation of vascular tone and blood flow primarily by mediating the vasoconstrictive effects of catecholamines [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Remarkably, the expression pattern of individual α1-AR subtypes and their involvement in mediating vascular responses to catecholamines differ considerably between individual vascular beds [34,36,37,38,39]. Members of the α2-AR subfamily are expressed in both the central and the peripheral nervous system throughout the body. They are localized either pre- or postsynaptically and mediate inhibition of neurotransmitter release [40,41]. β-ARs are widely distributed at both the central and peripheral nervous system and are involved in important functions activated by circulating catecholamines, such as heart rate regulation, vasorelaxation, bronchodilation, and neurotransmitter release [42].

Figure 1.

The three adrenoceptor (AR) subfamilies and their subtypes. α1-, α2-, and β-ARs mainly couple to Gq/11, Gi, and Gs proteins, respectively. To be more exact, the α2A-AR subtype has an unusual dual pharmacological effect by coupling to Gi proteins when concentrations of agonists are low and mainly coupling to Gs proteins when concentrations are high [43]. β-ARs are mainly coupled to Gs proteins and both β1- and β2-AR are able to switch their G protein-coupling specificity from Gs to Gi proteins [44].

The purpose of the present review is to summarize the current state of research on the role of α1-, α2- and β-ARs in the retina. We provide an overview of the expression, structural distribution, and regulation of the individual AR subfamilies and their subtypes in the retina and discuss their therapeutic implications.

2. The Retina

The retina is a thin multilayer with neuronal lamination responsible for detecting, preprocessing, and sending visual information to the brain [45]. The neuronal lamination in the retina includes neural circuits containing six major types of neuronal cells: retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), amacrine cells, bipolar cells, horizontal cells, and the cone and rod photoreceptors [46]. Despite the retina’s peripheral location, retinal neurons utilize the same types of neurotransmitters (noradrenaline, dopamine, and acetylcholine) as those of the central nervous system [47]. Since visual formation highly depends on the complex neuronal structure of the retina, a variety of detrimental factors, such as ischemia and oxidative stress, may result in the deterioration of retinal cell function and consequently lead to retinal diseases [48].

Two different circulatory systems are originating from the ophthalmic artery, the retinal circulation and the choroidal circulation, which both supply oxygen and nutrients to the retina [19]. While choroidal blood vessels are innervated and modulated by the autonomic nervous system, no sympathetic nerve fiber terminals have been found in or on the wall of human retinal blood vessels, suggesting that the retinal circulation lacks autonomic innervation [49]. Notably, retinal arterioles were shown to respond to local chemical factors, such as oxygen (O2), carbon dioxide (CO2), nitric oxide (NO), and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) [50,51,52]. Although no evidence for sympathetic nerve fibers has been provided in the retina, catecholamines, including noradrenaline, adrenaline and dopamine, have been detected [53]. One possible source of noradrenaline in the mammalian retina are sympathetic nerve terminals located in the choroid [54]. In support of this concept, a decrease in noradrenaline concentration has been observed in the retina after removal of the superior cervical ganglion, which provides sympathetic input to the choroid [53]. This finding indicates that noradrenaline may originate from sympathetic nerve terminals in the choroidal circulation and reach the ARs in the retina by paracrine diffusion [55].

Dopaminergic amacrine (DA) cells, a class of retinal neurons, synthetize and release dopamine, which is the prevailing catecholamine in the retina [56,57]. In the bovine retina, noradrenaline was detected in the inner nuclear and plexiform layers, and Osborne suggested that retinal tissue can metabolize dopamine to form noradrenaline [58]. Also, amacrine cells have been detected in the retina, which differs morphologically from DA cells and can be detected only after a preload with exogenous noradrenaline [54,59]. It has been proposed that these cells contain only small amounts of endogenous catecholamines, but are equipped with high-affinity uptake properties for exogenous catecholamines [54]. There is also compelling evidence indicating that in addition to noradrenaline, dopamine can also activate α1-, α2-, and β-ARs, but may be less potent [60]. Importantly, members of all three AR subfamilies, α1-, α2-, and β-ARs, have been detected in retinal tissue, including blood vessels [61].

3. Expression and Function of ARs in the Retina

3.1. α1-ARs

3.1.1. Expression of α1-ARs in the Retina

In contrast to choroidal blood vessels, the retinal vasculature seems to lack autonomic, i.e., adrenergic, cholinergic or peptidergic innervation [49,50,62,63,64]. However, α1-ARs have been found in retinal tissue of various mammalian species [65,66]. Particularly with regard to the intra-retinal vasculature, Forster et al. have demonstrated the presence of α1-adrenergic binding sites in homogenates of isolated bovine retinal arteries and veins, which were few in number, but of high agonist affinity [61]. In homogenates of isolated murine retinal arterioles, our laboratory has found mRNA for all three α1-AR subtypes, which were expressed at similar levels [67].

Several studies provided evidence that the cellular components of the three main layers of a vascular wall, i.e., endothelial cells of the intima, smooth muscle cells of the media, and fibroblasts of the adventitia, have the potential to express α1-ARs [29,30,31,32,33]. Furthermore, evidence has been provided that individual α1-ARs may exert distinct functions within one vessel [32,68,69]. For example, it has been suggested that in coronary arteries, endothelial α1B-ARs mediate vasodilation by stimulating endothelial nitric oxide synthase, while α1D-ARs localized on smooth muscle cells mediate vasoconstriction [68].

The cellular location of α1-ARs within the architecture of retinal blood vessels is still elusive but may have relevant pharmacological and pathophysiological implications. For example, with regard to α1-ARs located on retinal vascular smooth muscle cells, one would expect that the intact blood-retinal barrier prevents circulating hydrophilic molecules, such as catecholamines, from reaching these binding sites [70]. Conversely, they might become well-accessible in pathological states associated with an impaired endothelial barrier function [61,71]. Since a series of enzymes involved in catecholamine synthesis has been localized in retinal cells of different species, retinal vascular α1-ARs may also be a target of agonists released from surrounding retinal cells [72,73,74,75]. From a therapeutic point of view, the blood-retinal barrier may be circumvented by administering α1-adrenergic ligands into the vitreous body [76].

In addition to retinal vessels, Zarbin et al. localized α1-ARs in the outer plexiform layer of the rat retina in vitro by semiquantitative autoradiography using [3H]prazosin. The authors reported that α1-adrenergic binding sites were only enriched in the outer plexiform layer [77]. Other research groups demonstrated that α1-ARs are expressed on retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) of the rabbit and bovine retina, where they modulate K+ and Cl− transport and electrical currents [78,79]. Unfortunately, at present, antibody-based methods to localize α1-AR subtypes within the tissue structure appear to lack validity, since a growing body of evidence indicates that many commercially available antibodies directed against individual α1-AR subtypes do not specifically detect their alleged target antigen [80,81,82,83]. A combined approach of ligand-receptor binding techniques and immunostainings and/or functional studies in tissues from knockout (KO) animal models lacking the respective receptor subtype may represent a more suitable methodological alternative to determine the location and function of α1-ARs within the retina, which remains a subject of further research [28].

3.1.2. α1-ARs in Retinal Vascular Reactivity

In vivo studies performed in experimental animals and healthy humans have investigated the impact of systemically administered α1-adrenergic agonists on retinal vessel reactivity. The results, however, are partly contradictory, which makes it difficult to draw unequivocal conclusions regarding the functional role of α1-ARs in the regulation of retinal vascular resistance and perfusion. While Mori et al. observed a dose-dependent constriction of rat retinal arterioles in response to intravenous administration of noradrenaline, Alm et al. did not observe any effect of exogenously administered noradrenaline on retinal blood flow in cats [84,85]. Dollery et al. reported that intravenously administered noradrenaline decreased retinal vascular diameter in healthy humans, whereas other studies detected only a negligible impact of circulating noradrenaline and the α1-adrenergic agonist, phenylephrine, on human retinal vessel diameter and blood flow [86,87,88].

In general, in vivo studies investigating the effects of systemically applied adrenergic agonists or antagonists on retinal vascular responses are hampered by considerable changes in systemic blood pressure induced by these ligands. Due to the pronounced autoregulatory capability of the retinal vascular bed, the resulting changes in ocular perfusion pressure may also induce compensatory responses of the retinal vasculature, which makes it difficult to discern between direct pharmacological effects on retinal vessels and their reactive responses to systemic blood pressure changes [70,71,88,89]. This methodological dilemma may, at least in part, explain the contradictory results of the in vivo studies outlined above.

Ichikawa et al. and Hara et al. reduced systemic influences by intravitreal drug injection and observed constriction of rabbit retinal arteries in response to phenylephrine, which was attenuated after application of the α1-AR antagonist, bunazosin [76,90]. Additionally, in vitro studies using isolated eyes, retinal tissue grafts, and preparations of retinal arterioles also demonstrated a constrictive effect of α1-adrenergic agonists on retinal blood vessels [71,91,92,93,94].

In this context, Hoste et al. reported that on the one hand, the contractile response of bovine retinal arteries to α1-adrenergic stimulation was greatly masked under resting conditions [94]. On the other hand, retinal arteries became sensitive to α1-adrenergic agonists when activated by circumferential stretch and displayed an enhanced myogenic vasoconstrictor response to elevated perfusion pressure during α1-adrenergic stimulation [94]. In the study of Yu et al., the extent of vasoconstriction in isolated porcine retinal arterioles with intact endothelium in response to α1-adrenergic agonists differed between intra- and extra-luminal drug application. Adrenaline and noradrenaline caused concentration-dependent vasoconstriction, which was larger when applied intraluminally [70,92].

Although the aforementioned in vitro studies found a constrictive effect of α1-adrenergic agonists on retinal vessels with an intact endothelium, the reported vascular responses were mostly weak and had a relatively high threshold [91,92,93,94]. In a study conducted on murine retinal explants, our group has demonstrated that retinal arteriole constriction to α1-adrenergic stimulation is largely masked by endothelial mechanisms and becomes more relevant when the endothelium is damaged [67]. In contrast, a prior study of our own performed on endothelium-intact murine ophthalmic arteries under similar experimental conditions has shown pronounced vasoconstrictive responses to α1-adrenergic stimulation [67]. These findings suggest that endothelial modulation of α1-adrenergic vasoconstriction differs between retinal and retrobulbar blood vessels.

Due to its characteristic properties, the endothelium of retinal vessels represents a mechanical barrier, which is considered to prevent most blood-borne hydrophilic compounds, including catecholamines, from reaching vascular smooth muscle cells [20,50,62,63,64,70,95]. In the referred study, however, the blood-retinal barrier was circumvented, since vasoactive substances were applied extraluminally [67]. Therefore, the observed attenuating influence of the endothelium most likely results from endothelium-derived vascular mechanisms that functionally antagonize constrictive responses of retinal arterioles to α1-adrenergic stimuli. Endothelium-dependent attenuation of retinal α1-AR-mediated vasoconstriction appears physiologically plausible, since it would confer a safety net by protecting the retina against inappropriate reductions in blood flow induced by elevated levels of catecholamines during exercise, hemorrhage, or stress. Based on studies in various vascular beds, including cerebral vessels, it is well documented that vascular responses to α1-adrenergic stimuli are modulated by the vascular endothelium and are altered when endothelial function is impaired [96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106]. Apparently, the endothelium mitigates the vasoconstrictive impact of elevated circulating catecholamine levels particularly in organs whose uncompromised blood supply and functioning are of vital importance during fight and flight responses [34,39,107]. Conversely, under conditions of endothelial impairment, e.g., in atherosclerosis and diabetes, vascular sensitivity to α1-adrenergic vasoconstrictors appears to be increased [107,108,109,110,111,112].

In general, endothelial compensation of α1-AR-mediated vasoconstriction is attributed to relaxing factors, such as nitric oxide, released by endothelial cells [113,114,115,116,117,118,119]. While nitric oxide release in response to increased shear stress during vascular constriction is considered a possible endothelial mechanism counteracting vasoconstriction, some other studies suggest that activation of α1-ARs located on endothelial cells also promotes the endothelial release of nitric oxide, functionally antagonizing adrenergic vasoconstriction [29,107,120,121,122,123,124,125].

Retinal pathologies, such as diabetic retinopathy, arterial occlusive disease or glaucoma, are associated with impaired endothelial function [12,126,127,128]. However, so far, no compelling evidence has been provided that under retinal pathological conditions α1-AR-mediated vasoconstriction becomes a relevant contribution factor, although an in vivo study in rabbits suggested that blockade of α1-AR signaling may alleviate the impairment in blood flow and retinal function caused by nitric oxide synthase inhibition [129].

3.1.3. Contribution of Individual α1-AR Subtypes to Vascular Reactivity in the Retina

In their in vivo study, Mori et al. aimed to identify the α1-AR subtype(s) involved in noradrenaline-induced constriction of retinal arterioles in anaesthetized rats by analyzing the vascular effects of systemically administered subtype-preferring agonists and antagonists. The authors concluded from their results that vascular constriction to noradrenaline in rat retinal arterioles is primarily mediated by the α1A- and the α1D-AR, and that this finding corresponds to the situation in the rat peripheral circulation [84]. From a methodological point of view, the interpretation of the results is hampered by the confounding influence of retinal vascular autoregulation in an in vivo setting and by the lack of highly selective agonists and antagonists for all α1-AR subtypes [24,28,35,70,71,88,89,130,131].

Using an in vitro approach and gene-targeted mice deficient in individual α1-AR subtypes, our group has recently demonstrated that α1-AR-mediated vasoconstriction in retinal arterioles with damaged endothelium is predominantly conveyed by the α1B-AR subtype [67]. By contrast, in the murine ophthalmic artery, which is directly afferent to the retinal vasculature, the α1A-AR subtype has previously been shown to mediate constrictive responses to adrenergic stimuli [132]. These results indicate that the retrobulbar (α1A-AR) and the retinal (α1B-AR) vasculature are under the functional control of different α1-AR subtypes. This finding is in line with previous studies reporting that the distribution of individual α1-AR subtypes and their contribution to adrenergic vasoconstriction varies considerably between circulatory beds, between different-sized vessels of a given vascular bed, and between different species [24,34,39,133,134,135].

Although mRNA for all three α1-AR subtypes was found to be expressed at similar levels in murine retinal arterioles, α1-AR-mediated vasoconstriction is predominantly mediated by the α1B-AR subtype [67]. Several studies have provided evidence that the presence of mRNA or protein of a particular α1-AR subtype does not necessarily go along with its participation in vasoconstriction [31,132,136,137,138]. Furthermore, each receptor subtype can activate distinct downstream signaling components in the Gq/11 signaling pathways and also couple to other independent signaling pathways [35,36,131,139,140,141]. Therefore, a particular α1-AR subtype that does not contribute to vasoconstriction despite its expression may, nevertheless, be involved in the regulation of other physiological or pathophysiological processes of the retinal vasculature. However, whether these results derived from animal models correctly represent the expression and function of α1-AR subtypes in the human retinal vasculature remains to be elucidated.

3.2. α2-ARs

3.2.1. Expression of α2-ARs in the Retina

In 1982, Osborne detected retinal α2-ARs in the bovine retina in binding studies utilizing [3H]noradrenaline and [3H]clonidine [142]. In 1986, α2-AR binding sites were identified in the inner plexiform layer of the rat retina by [3H]para-aminoclonidine ([3H]PAC) [77]. Most of these sites were also related to the proximal layer of cell bodies in the inner nuclear layer and with some putative displaced amacrine or ganglion cell bodies [77]. Furthermore, α2-ARs were identified in calf retinal cellular membranes by binding experiments employing the radiolabelled antagonists, [3H]-RX 781,094 and [3H]-rauwolscine [143]. Matsuo and Cynader found α2-AR binding sites in the retina of human cadaveric eyes by an in vitro ligand-binding technique and autoradiography [144].

Three distinct subtypes of α2-ARs, α2A, α2B, α2C, have been identified by molecular and pharmacological characterization techniques [145]. The International Union of Pharmacology has identified species orthologues and termed them α2A-AR in humans and α2D-AR in rats and mice [27]. Venkataraman et al. indicated that the α2D-AR gene in the bovine retina was a structural variant of the rat and mouse genes and defined the α2D-AR subtype in the bovine retina [146]. The expression of the α2D-AR subtype was detected in the bovine retina and its photoreceptors [146]. Messenger RNA of the α2D-AR was identified in the bovine retina by amplification through reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) [146]. It is now generally accepted that the α2D-AR represents a species variant of the α2A-AR [147].

Immunohistochemical studies revealed the presence of α2-ARs (specifically α2A-ARs) on rat RGCs and inner nuclear layer cells [148]. In the human retina, Kalapesi et al. found α2A-ARs on human RGCs and cells in the inner and outer nuclear layers [148].

In addition, Pfizer et al. reported that in rat retinas, α2A-ARs were mainly found in the cell bodies located in the ganglion cell layer, the inner plexiform layer and the outer plexiform layer [149]. In other immunohistochemical studies, α2A-AR staining was also observed in the membrane of cells located in the inner nuclear layer, specifically amacrine and horizontal cells. In human and monkey retinas, the α2A-AR staining pattern was relatively consistent with that observed in rats [149]. In contrast to α2A-ARs, α2B-AR immunoreactivity was observed in all retinal layers, especially in the presynaptic regions of neurons. In the outer retina, α2B-AR immunoreactivity was seen in more than one cell type, such as the inner segments of photoreceptors, Müller cells, and bipolar cells [149]. Moreover, Pfizer et al. observed that α2A-ARs were mainly present in the cell membrane of photoreceptor cells and in their inner segments [149]. Notably, some studies reported that many commercially available antibodies directed against ARs, including α2-ARs, lack sufficient specificity [80,82,83]. Based on these findings, expression studies employing commercially available AR antibodies need to be interpreted with caution [82].

3.2.2. α2-AR in Retinal Neuroprotection

The family of α2-ARs is one of the pharmacological targets of the natural stress hormone, norepinephrine, and is involved in modulating cellular resistance and adaptation to stress stimuli [150]. α2-ARs were first described as presynaptic receptors inhibiting the release of various transmitters from neurons in the central and peripheral nervous systems [151]. In vivo studies revealed that α2-AR stimulation reduces ischemic injury in the brain [152]. This effect has been largely attributed to its classic presynaptic inhibition of signaling molecules released by blocking Ca2+ channels, activating K+ channels, or reducing active release sites [153,154]. Neuroprotective treatment strategies for retinal diseases whose course includes neuronal degeneration have arisen a great deal of interest. Some studies have assessed the functional role of α2-ARs in the retina in a variety of animal models through the mechanism of α2-mediated neuroprotection. For example, Donello et al. suggested that activation of α2-ARs might reduce ischemic retinal injury and preserve retinal function following transient ischemia by preventing extracellular glutamate and aspartate accumulation [155]. An in vivo study by Manuel et al. revealed neuroprotective effects of α2-ARs in preventing RGC death after transient retinal ischemia [156]. In the study, pre-treatment with two α2-AR-selective agonists, AGN 191,103 and brimonidine tartrate, has proven very effective not only in preventing rapid RGCs loss, but also long-term RGCs loss in a rat model [156].

Glaucoma with elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) often continues to progress even after the reduction of IOP to normal levels [5]. The progressive loss of vision in eyes with glaucoma is a result of RGCs degeneration, emphasizing the need for a neuroprotective therapy [157]. The α2-AR agonist, brimonidine, and other α2-AR agonists were shown to lower IOP mainly by reducing aqueous humor production and by increasing uveoscleral outflow [158,159,160]. In a rat model of chronically elevated IOP, pharmacological activation of α2-ARs exerted neuroprotective effects in RGCs, irrespective of the IOP level [157]. In addition, the α2-AR agonist, brimonidine, preserved visual function in glaucoma patients with low/normal IOP and high IOP, suggesting that pharmacological α2-AR activation may exert neuroprotective effects IOP independently [161,162,163]. Various mechanisms underlying the neuroprotective activity of α2-AR agonists have been proposed. For example, activation of α2-ARs was shown to decrease the IOP-induced overexpression of intermediate filament glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in Müller cells, suggesting that activation of α2-ARs may reduce stress responses in glial cells. [157]. Furthermore, the α2-AR agonist, brimonidine, was reported to protect RGCs from the effects of chronic ocular hypertension through mechanisms involving α2-AR-mediated survival signal activation and up-regulation of endogenous neurotrophic factors in the rat retina [164]. Another study demonstrated that α2-adrenergic modulation of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor function was an important mechanism for neuroprotection in experimental glaucoma models [154]. Brimonidine may protect RGCs by preventing abnormal elevation of cytosolic free Ca2+ evoked by NMDA receptors in RGCs under stress conditions [165,166]. Other studies suggested that brimonidine-mediated inhibition of the cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate/protein kinase A (cAMP/PKA) pathway could be an important mechanism to protect RGCs from glaucomatous neurodegeneration [162]. Based on a recent study in a rat glaucoma model, Zhou et al. suggested that α2-AR activation hyperpolarizes RGCs by improving the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor response to spontaneous and elicited GABA release, thus reducing the risk for excitotoxicity and RGC injury [167].

Activation of α2-ARs has also been shown to exert neuroprotective effects in other retinal diseases, such as light-induced photoreceptor damage, retinal detachment, and optic nerve injury [168,169,170]. For example, α2-adrenergic agonists were shown to induce the expression of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) in photoreceptors in vivo and to alleviate light-induced damage in the retina [168]. In retinal detachment, stimulation of α2-AR signaling protected photoreceptors by inhibiting oxidative stress and inflammation [170]. Furthermore, in a mouse optic neuritis model, topical administration of the α2-AR agonist, brimonidine, exerted neuroprotective effects against RGCs death by increasing retinal bFGF expression in the retina, particularly in Müller cells and RGCs [171]. In contrast, in mechanic optic nerve injury, activation of α2-AR signaling promoted optic nerve regeneration via activation of extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK) phosphorylation [169].

Activation of α2-ARs was suggested to induce vasoconstriction in the vasculature distal to the ophthalmic artery, such as ciliary and retinal blood vessels [172,173,174]. While the α2A-AR subtype was proposed to mediate adrenergic vasoconstriction in porcine ciliary arteries, no suggestion regarding the contribution of individual α2-AR subtypes has been made for retinal blood vessels [172].

Only little is known about the functional role of individual α2-AR subtypes in the retina. A study by Harun-Or-Rashid et al. showed that α2A-ARs are expressed by chicken Müller cells and that pharmacological activation of the α2A-AR subtype triggers a mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-dependent response with phosphorylation of ERK1/2 both in vivo and in vitro. Taken together, most studies indicate that activation of α2-ARs raises neuronal resistance to retinal injury suggesting that the receptors may become potent treatment targets in various retinal diseases. However, the role of individual α2-AR subtypes remains to be better characterized in the retina.

3.3. β-ARs

3.3.1. Expression of β-ARs in the Retina

In 1986, Zarbin et al. localized β-AR binding sites by [3H]dihydroalprenolol in nearly all rat retinal layers (the outer nuclear layer, outer plexiform layer, inner nuclear layer, and inner plexiform layer), but with the lowest concentration in the outer nuclear layer [77]. In the human retina, β-AR binding sites were visualized by [125I] (-) iodocyanopindolol in vitro autoradiography [175].

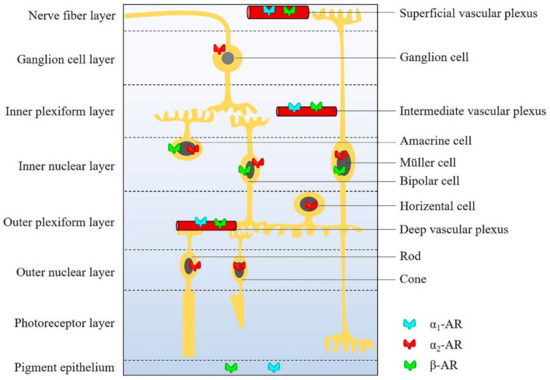

Three distinct β-AR subtypes, β1-AR, β2-AR and β3-AR, have been identified [176]. In 2001, the β4-AR was hypothesized by Granneman as a novel state of the β1-AR [176]. Six years later, the β4-AR was considered by Madamanchi as a low-affinity state of the β1-AR, which still needs pharmacological and genetic characterization [177]. Among β-AR subtypes, β1-AR and β2-AR binding sites were found in bovine retinal vessels and in the neural retina [178]. The presence of functional β3-ARs has also been verified in rat retinal blood vessels [179]. By immunohistochemistry, β3-ARs were localized in the inner capillary plexus of the mouse mid-peripheral retina, whereas β1-ARs and β2-ARs were localized in rat cultured Müller cells [180]. However, since many commercially available antibodies lack sufficient specificity for β-ARs, data based on antibodies need to be interpreted with caution [83]. Expression of β3-ARs has been shown for the first time on cultured human retinal endothelial cells in 2003 [181]. In that study, pharmacological activation of β3-ARs promoted migration and proliferation of endothelial cells [181]. Based on the wide distribution of β-ARs in retinal blood vessels and the neural retina, β-ARs are believed to play an important role in retinal vascular and neuronal function. The localization of individual AR subfamilies in individual retinal layers and structures is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The distribution of ARs in individual retinal layers and structures.

3.3.2. Role of β-ARs in the Retina

Stress conditions, such as hypoxia, can cause catecholaminergic overstimulation in the cardiovascular system, which in turn may activate β-ARs [182]. A study in mice reported that the noradrenaline level increased by approximately 90% in the hypoxic retina compared to normoxic conditions [183]. Activation of β-ARs is considered to upregulate the hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which plays a key role in the formation of pathogenic blood vessels in various retinal diseases, such as retinopathy of prematurity and diabetic retinopathy [183,184,185]. The β-AR blocker, propranolol, effectively inhibited the increase of VEGF expression caused by hypoxia and the consecutive neovascular response in the retina [55]. Likewise, propranolol administered subcutaneously reduced VEGF and HIF-1α levels in an oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) mouse model, suggesting that β-AR blockade was protective against retinal angiogenesis and ameliorated blood-retinal barrier dysfunction [186].

Intriguingly, a novel β-AR agonist, compound 49b, was reported to decrease VEGF levels in the diabetic rat retina [187]. The effect of compound 49b was attributed to an increase in insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 (IGFBP-3), which reduced VEGF levels via modulation of eNOS and PKC pathways [187]. These seemingly contradictory findings regarding the impact of β-AR agonists and antagonists on VEGF levels suggest that the effects may be mediated through diverse regulation mechanisms depending on the retinal disease and the experimental setting.

β-AR activation was also shown to increase human and mouse pericyte survival under diabetic conditions [188]. Conversely, a significant decrease in the number of pericytes has been reported in the rat retina after surgical removal of the superior cervical ganglion, which supplies the eye with sympathetic nerve fibers [189]. These findings suggest that proper β-AR signaling is essential for pericyte survival. An in vitro study proposed that β-ARs are involved in the regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression [190]. Activation of β-ARs reduced levels of iNOS and other inflammatory molecules, such as interleukin (IL)-1β, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in human retinal endothelial cells and rat Müller cells in an in vitro model of hyperglycemia [191]. The proposed mechanism for the protective effects was that the stimulating β-ARs decrease the levels of the MAPK family members, PKA, p38 MAPK, and p42/p44 MAPK, in human retinal endothelial cells [190].

Stimulation of β-AR by agonists can activate members of the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) kinase (GRK) family, which is the potential mechanism that leads to β-AR desensitization [192]. A first mechanism underlying desensitization is phosphorylation of the GPCR [193]. After coupling to activated receptors, G proteins are phosphorylated by GRKs [194,195]. Seven GRKs (GRK1–7) have been identified, at present [196]. GRK1, as a rhodopsin kinase, is responsible for phosphorylating rhodopsin, which is richly expressed in the retinal rod and cone cells [197]. β-ARs can be phosphorylated by a protein kinase termed GRK2 [198]. The GRK-phosphorylated receptor binds to arrestins, leading to the uncoupling of the receptor from the G protein, desensitizing the agonist-induced response, and subsequently mediating the internalization of receptors [195,199]. Consequently, the GRK-arrestin pathway plays a central role in the desensitization of GPCR responses [195,199]. Two arrestin subtypes were found to be expressed in the retina, arrestin-1 and -4. These arrestins are specialized in binding light-activated phosphorylated rhodopsin and suppressing G protein activation [200,201]. It has been demonstrated that retinal and nonretinal arrestins mediate suppression of GPCRs, suggesting a common mechanism for desensitizing ARs [202]. Apart from this role, arrestins were also shown to be involved in receptor-mediated endocytosis by clathrin-coated pits [202,203].

3.3.3. Contribution of Individual Receptor Subtypes to β-Adrenergic Function in the Retina

Hypoxia was reported to trigger the release of catecholamines, which have been shown to contribute to the increase in retinal VEGF expression, causing pathologic neovascularization [183,184,185]. In a mouse model of OIR, deletion of β1- and β2-ARs reduced retinal VEGF receptor-2 expression and abolished the development of vascular abnormalities in the superficial plexus of the retina [204]. In another study employing a mouse model of OIR, β1- and β2-AR blockade by propranolol was shown to reduce the expression of VEGF and to ameliorate retinal dysfunction [186]. Other studies demonstrated that ICI 118,551, a selective β2-AR blocker, decreased retinal levels of proangiogenic factors and reduced pathogenic neovascularization in a mouse OIR model, suggesting that β2-AR blockade may be effective in the blockade of retinal angiogenesis [205].

As we mentioned before, there are inconsistent results regarding the role of β-AR activation or blockade on VEGF expression and pathogenic vessel formation. While most studies reported on inhibitory effects of pharmacological β-AR blockade on VEGF formation some other studies observed blockade of VEGF formation by β-AR agonist exposure [55,182,183,184,185,186]. An explanation to these seemingly contradictory results provides a study by Dal Monte et al., which suggested that the nonselective β-ARs agonist, isoproterenol, can cause agonist-induced β2-AR desensitization that downregulates the expression of β2-ARs in the retina, which in turn exerts a downregulation effect on VEGF expression in OIR [183]. Jiang et al. proposed that β2-AR KO mice exhibited certain features similar to diabetic retinopathy, resulting in retinal cell death [206]. A study in β2-AR KO mice has shown a functional link between β-ARs and insulin receptor signaling pathways in the retina [200]. Furthermore, β2-ARs can maintain insulin receptor signaling in retinal Müller cells, which potentially supports neuroprotective effects promoted by β-AR stimulation in diabetic retinopathy models [200]. Xamoterol, a β1-AR agonist, attenuated iNOS expression in human retinal endothelial cells grown in high glucose medium [191]. Studies by Mori et al. have demonstrated that stimulation of β1-, β2-, and β3-ARs can cause dilation of retinal arterioles in rats, thus, increasing retinal blood flow [207,208]. Moreover, the latest study by Mori et al. reported that retinal vasodilation by β2-AR stimulation is mediated via a Gi protein by activation of large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels [209].

β3-ARs were shown to be involved in the neovascularization processes of various retinal vascular diseases [186]. For example, β3-ARs were upregulated in response to hypoxia in an OIR mouse model with dense β3-ARs immunoreactivity in engorged retinal tufts, suggesting that activation of β3-ARs is likely to constitute an important part in pathologic angiogenesis [186]. It has also been demonstrated that the β3-AR antagonists, L-748,337 and SR59230A, downregulated retinal VEGF release in hypoxia via modulation of the nitric NO signaling pathway [210]. Moreover, the β3-AR agonist, CL316243, was shown to reduce retinal damage following intravitreal injection of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) in rats [211]. Furthermore, β3-ARs, which differ from β2-ARs with regard to a lack of GRK, are resistant to agonist-induced desensitization [192,212]. Taken together, based on the studies performed so far, the β3-AR appears to be an attractive therapeutic target for the treatment of ischemic retinal diseases.

Notably, β-AR genes have genetic polymorphisms caused by mutations in the gene promoter, leading to changes in the expression of receptors and the regulation of signal transduction [195,213,214]. The mutations of ARs mainly affect receptor responses and are associated with some diseases [214]. An in vivo study tested the effects of two polymorphisms (codon 16 and codon 27) of the β2-AR on agonist-mediated vascular desensitization, suggesting that the arginine at position 16 (Arg16) polymorphism (the substitution of glycine for arginine) of the β2-AR is associated with enhanced agonist-mediated desensitization in the vasculature [215]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no association between genetic polymorphisms of β-AR genes and retinal diseases has been described, so far.

4. Future Directions and Clinical Implications

Although α1-ARs play a potential physiological and/or pathophysiological role in the regulation of retinal vascular tone, retinal α1-adrenergic vasoconstriction is largely masked by endothelial mechanisms under physiological conditions and becomes more relevant when the endothelium is damaged. Therefore, α1-AR signaling pathways may represent therapeutic targets primarily in the context of retinal pathologies associated with impaired endothelial function. However, there are inconsistent findings regarding the subtype mediating adrenergic vasoconstriction in retinal blood vessels. While Mori et al. found that α1A- and α1D-ARs mediated vasoconstriction in vivo in the rat retina, Gericke et al. reported that the α1B-AR-mediated adrenergic vasoconstriction in the isolated mouse retina [67,84]. It remains to be determined which α1-AR subtype mediates vascular responses in the human retina. However, the lack of highly specific pharmacological ligands and antibodies for individual α1-AR subtypes hampered the progress in this research area so far. From a clinical point of view, subtype-selective agonists and antagonists would constitute a therapeutic approach to specifically influence retinal perfusion.

It should be emphasized, however, that many issues remain poorly understood and need further investigation. The location of α1-ARs in general and of the three α1-AR subtypes in particular within the architecture of retinal vessels is still elusive but may be indicative of their vascular function(s) and relevant for their pharmacological accessibility. The endothelial mechanisms involved in masking retinal α1-adrenergic vasoconstriction have not yet been identified. In retinal diseases associated with endothelial dysfunction, the actual pathogenic contribution of α1-AR-mediated vasoconstriction remains an open question.

Various animal experiments and cell culture studies revealed neuroprotective effects of the selective α2-AR agonist, brimonidine, in the retina [148,150,216]. In 2011, a randomized clinical trial reported on the neuroprotective effects of topically applied brimonidine tartrate 0.2% in preventing visual field loss progression in patients with low-pressure glaucoma, which supports the concept of direct activation of retinal α2-ARs [163]. In contrast, another trial failed to show neuroprotective effects of 0.2% brimonidine tartrate in patients with non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy [217]. In a pilot study on patients with retinal dystrophies, topical treatment with brimonidine suggested a trend towards reduced disease progression [218]. However, the number of patients (n = 26) was relatively small and the mean follow-up period (mean 29 months) relatively short, which does not allow to draw unequivocal conclusions. Taken together, the retinal neuroprotective effects of brimonidine obtained in various experimental disease models remain to be confirmed in large human trials.

Propranolol, which has a high affinity to β1- and β2-AR subtypes, is the only β-AR antagonist that has been tested in clinical trials, so far [55]. Propranolol 0.1% eye micro-drops have been developed and administered in a multicenter pilot clinical trial to analyze the safety and efficacy in treating preterm newborns with stage 2 ROP [219]. However, the second stage of this study was discontinued, since the fourth of the 19 newborns showed a progression to stage 2 or 3 with additional disease [219]. Based on animal studies, β3-ARs appear to be involved in pathogenic vessel formation in the ischemic retina. Hence, future studies are needed to explore β3-AR ligands in human ischemic retinal diseases.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the studies reviewed in this article provide evidence for the presence of α1-, α2- and β-ARs in the retina of various species, including humans. α1-ARs function as stimulatory receptors involved mainly in the contraction of vascular smooth muscle, resulting in vasoconstriction. In contrast, α2-ARs are primarily expressed in neurons and glia. Its pharmacological activation was shown to lower IOP and to induce neuroprotective effects in the retina. β-ARs are expressed in blood vessels, neurons and glial cells, where they were shown to contribute to the regulation of vascular diameter and to responses to hypoxia. The results of numerous in vitro and in vivo studies suggest that these retinal receptors are functionally active and, hence, may constitute potential targets for the treatment of several retinal diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.B., Y.R. and A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, T.B. and Y.R.; writing—review and editing, A.G., S.J., and T.B.; visualization, Y.R.; supervision, A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Brown, M.M.; Brown, G.C. Utility values associated with blindness in an adult population. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2001, 85, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.M.; Brown, G.C. Quality of life associated with visual loss: A time tradeoff utility analysis comparison with medical health states. Ophthalmology 2003, 110, 1076–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, U.; Ajanaku, D. Uveitis: A sight-threatening disease which can impact all systems. Postgrad. Med. J. 2017, 93, 766–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biousse, V.; Nahab, F. Management of acute retinal ischemia: Follow the guidelines! Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 1597–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quigley, H.A.; Broman, A.T. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2006, 90, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, Y.M.; Gariano, R.F. Diabetic retinopathy: A growing concern in an aging population. Geriatrics 2009, 64, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmani, B.; Tielsch, J.M. The cause-specific prevalence of visual impairment in an urban population. The baltimore eye survey. Ophthalmology 1996, 103, 1721–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocur, I.; Resnikoff, S. Visual impairment and blindness in europe and their prevention. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2002, 86, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congdon, N.G.; Friedman, D.S. Important causes of visual impairment in the world today. JAMA 2003, 290, 2057–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, N.N.; Casson, R.J. Retinal ischemia: Mechanisms of damage and potential therapeutic strategies. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2004, 23, 91–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieshaber, M.C.; Flammer, J. Blood flow in glaucoma. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2005, 16, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toda, N.; Nakanishi-Toda, M. Nitric oxide: Ocular blood flow, glaucoma, and diabetic retinopathy. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2007, 26, 205–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flammer, J.; Orgul, S. The impact of ocular blood flow in glaucoma. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2002, 21, 359–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmetterer, L.; Wolzt, M. Ocular blood flow and associated functional deviations in diabetic retinopathy. Diabetologia 1999, 42, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, G.; Kato, S. Relation between retrobulbar circulation and progression of diabetic retinopathy. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2003, 87, 622–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, A.; Suzuki, S. Vasodilation of retinal arterioles induced by activation of bkca channels is attenuated in diabetic rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 669, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Cruz, J.P.; Gonzalez-Correa, J.A. Pharmacological approach to diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2004, 20, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong-Riley, M.T.T. Energy metabolism of the visual system. Eye Brain 2010, 2, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kur, J.; Newman, E.A. Cellular and physiological mechanisms underlying blood flow regulation in the retina and choroid in health and disease. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2012, 31, 377–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaey, C.; Van De Voorde, J. Regulatory mechanisms in the retinal and choroidal circulation. Ophthalmic Res. 2000, 32, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, N.; Aslam, T. Retinal vascular image analysis as a potential screening tool for cerebrovascular disease: A rationale based on homology between cerebral and retinal microvasculatures. J. Anat. 2005, 206, 319–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlquist, R.P. A study of the adrenotropic receptors. Am. J. Physiol. 1948, 153, 586–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, S.P.; Benson, H.E. The concise guide to pharmacology 2013/14: G protein-coupled receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 170, 1459–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piascik, M.T.; Perez, D.M. Alpha1-adrenergic receptors: New insights and directions. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001, 298, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Civantos Calzada, B.; Aleixandre de Artinano, A. Alpha-adrenoceptor subtypes. Pharmacol. Res. 2001, 44, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikberg-Matsson, A. Α1- and α2-Adrenoceptors in the Eye: Pharmacological and Functional Characterization. Ph.D. Thesis, Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, Upsaliensis, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bylund, D.B.; Eikenberg, D.C. International union of pharmacology nomenclature of adrenoceptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 1994, 46, 121–136. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, J.C. Localization of α-adrenoceptors: Jr vane medal lecture. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 172, 1179–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttle, J.L.; Falcone, J.C. Nitric oxide release during alpha1-adrenoceptor-mediated constriction of arterioles. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2001, 281, H873–H881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gericke, A.; Martinka, P. Impact of alpha1-adrenoceptor expression on contractile properties of vascular smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2007, 293, R1215–R1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hrometz, S.L.; Edelmann, S.E. Expression of multiple alpha1-adrenoceptors on vascular smooth muscle: Correlation with the regulation of contraction. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999, 290, 452–463. [Google Scholar]

- Faber, J.E.; Yang, N. Expression of alpha-adrenoceptor subtypes by smooth muscle cells and adventitial fibroblasts in rat aorta and in cell culture. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001, 298, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ciccarelli, M.; Santulli, G. Endothelial alpha1-adrenoceptors regulate neo-angiogenesis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 153, 936–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimaraes, S.; Moura, D. Vascular adrenoceptors: An update. Pharmacol. Rev. 2001, 53, 319–356. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cotecchia, S. The alpha1-adrenergic receptors: Diversity of signaling networks and regulation. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res. 2010, 30, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, R.M.; Perez, D.M. Alpha 1-adrenergic receptor subtypes. Molecular structure, function, and signaling. Circ. Res. 1996, 78, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosoda, C.; Tanoue, A. Correlation between vasoconstrictor roles and mrna expression of alpha1-adrenoceptor subtypes in blood vessels of genetically engineered mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2005, 146, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, D.; Miquel, R. Correlation between mrna levels and functional role of alpha1-adrenoceptor subtypes in arteries: Evidence of alpha1l as a functional isoform of the alpha1a-adrenoceptor. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005, 289, H1923–H1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rudner, X.L.; Berkowitz, D.E. Subtype specific regulation of human vascular alpha(1)-adrenergic receptors by vessel bed and age. Circulation 1999, 100, 2336–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouin, C.; Bobadilla, A.-C. Norepinephrine☆. In Reference Module in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hieble, J.P. Adrenergic receptors. In Encyclopedia of Neuroscience; Squire, L.R., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 135–139. [Google Scholar]

- Djurup, R. Adrenoceptors: Molecular nature and role in atopic diseases. Allergy 1981, 36, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, L.; Zhou, Q. Structural basis of the diversity of adrenergic receptors. Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 2929–2935.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magocsi, M.; Vizi, E.S. Multiple g-protein-coupling specificity of beta-adrenoceptor in macrophages. Immunology 2007, 122, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amini, R.; Rocha-Martins, M. Neuronal migration and lamination in the vertebrate retina. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masland, R.H. The neuronal organization of the retina. Neuron 2012, 76, 266–280. [Google Scholar]

- Haider, N.B.; Cruz, N.M. Pathobiology of the outer retina: Genetic and nongenetic causes of disease. In Pathobiology of Human Disease; McManus, L.M., Mitchell, R.N., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 2084–2114. [Google Scholar]

- Herzlich, A.A.; Patel, M. Chapter 2—Retinal anatomy and pathology. In Retinal Pharmacotherapy; Nguyen, Q.D., Rodrigues, E.B., Eds.; W.B. Saunders: Edinburgh, UK, 2010; pp. 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, M.J.; Feeney, L. The ultrastructure of the retinal blood vessels: I. The large vessels. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 1963, 9, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari-Dileo, G.; Davis, E.B. Biochemical evidence for cholinergic activity in retinal blood vessels. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1989, 30, 473–477. [Google Scholar]

- Gericke, A.; Goloborodko, E. Contribution of nitric oxide synthase isoforms to cholinergic vasodilation in murine retinal arterioles. Exp. Eye Res. 2013, 109, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Mercieca, K. Hydrogen sulfide and β-synuclein are involved and interlinked in the aging glaucomatous retina. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 2020, 8642135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjiconstantinou, M.; Cohen, J. Epinephrine: A potential neurotransmitter in retina. J. Neurochem. 1983, 41, 1440–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Legros, J. Chapter 5 morphology and distribution of catecholamine-neurons in mammalian retina. Prog. Retin. Res. 1988, 7, 113–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casini, G.; Dal Monte, M. The β-adrenergic system as a possible new target for pharmacologic treatment of neovascular retinal diseases. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2014, 42, 103–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirasawa, H.; Contini, M. Extrasynaptic release of gaba and dopamine by retinal dopaminergic neurons. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20140186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HÄGgendal, J.A.N.; Malmfors, T. Identification and cellular localization of the catecholamines in the retina and the choroid of the rabbit. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1965, 64, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborne, N.N. Noradrenaline, a transmitter candidate in the retina. J. Neurochem. 1981, 36, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frederick, J.M.; Rayborn, M.E. Dopaminergic neurons in the human retina. J. Comp. Neurol. 1982, 210, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S. Cross interaction of dopaminergic and adrenergic systems in neural modulation. Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol. 2014, 6, 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, B.A.; Ferrari-Dileo, G. Adrenergic alpha 1 and alpha 2 binding sites are present in bovine retinal blood vessels. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1987, 28, 1741–1746. [Google Scholar]

- Ehinger, B. Distribution of adrenergic nerves in the eye and some related structures in the cat. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1966, 66, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laties, A.M. Central retinal artery innervation. Absence of adrenergic innervation to the intraocular branches. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1967, 77, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.D.; Laties, A.M. Peptidergic innervation of the retinal vasculature and optic nerve head. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1990, 31, 1731–1737. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, F.; Taniguchi, T. Distribution of alpha-1 adrenoceptor subtypes in rna and protein in rabbit eyes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002, 135, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikberg-Matsson, A.; Uhlen, S. Characterization of alpha(1)-adrenoceptor subtypes in the eye. Exp. Eye Res. 2000, 70, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohmer, T.; Manicam, C. The alpha1b-adrenoceptor subtype mediates adrenergic vasoconstriction in mouse retinal arterioles with damaged endothelium. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 3858–3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, B.C.; Swigart, P.M. Functional alpha-1b adrenergic receptors on human epicardial coronary artery endothelial cells. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2010, 382, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, B.C.; Swigart, P.M. The alpha-1d is the predominant alpha-1-adrenergic receptor subtype in human epicardial coronary arteries. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 54, 1137–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.Y.; Su, E.N. Isolated preparations of ocular vasculature and their applications in ophthalmic research. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2003, 22, 135–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari-Dileo, G.; Davis, E.B. Response of retinal vasculature to phenylephrine. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1990, 31, 1181–1182. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjiconstantinou, M.; Mariani, A.P. Immunohistochemical evidence for epinephrine-containing retinal amacrine cells. Neuroscience 1984, 13, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, H.; Cuenca, N. The synaptic organization of the dopaminergic amacrine cell in the cat retina. J. Neurocytol. 1990, 19, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Legros, J.; Krieger, M. Immunohistochemical localization of l-dopa and aromatic l-amino acid-decarboxylase in the rat retina. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1994, 35, 2906–2915. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Jia, W. Immunohistochemical localization of dopamine-beta-hydroxylase in human and monkey eyes. Curr. Eye Res. 1999, 18, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, M.; Okada, Y. Effects of topically instilled bunazosin, an alpha1-adrenoceptor antagonist, on constrictions induced by phenylephrine and et-1 in rabbit retinal arteries. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004, 45, 4041–4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zarbin, M.A.; Wamsley, J.K. Autoradiographic localization of high affinity gaba, benzodiazepine, dopaminergic, adrenergic and muscarinic cholinergic receptors in the rat, monkey and human retina. Brain Res. 1986, 374, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, D.P.; Miller, S.S. Alpha-1-adrenergic modulation of k and cl transport in bovine retinal pigment epithelium. J. Gen. Physiol. 1992, 99, 263–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frambach, D.A.; Valentine, J.L. Alpha-1 adrenergic receptors on rabbit retinal pigment epithelium. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1988, 29, 737–741. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, B.C.; Swigart, P.M. Ten commercial antibodies for alpha-1-adrenergic receptor subtypes are nonspecific. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2009, 379, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, M.C.; Seifert, R. Selectivity of pharmacologic tools: Implications for use in cell physiology. A review in the theme: Cell signaling: Proteins, pathways and mechanisms. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2015, 308, C505–C520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradidarcheep, W.; Stallen, J. Lack of specificity of commercially available antisera against muscarinergic and adrenergic receptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2009, 379, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bohmer, T.; Pfeiffer, N. Three commercial antibodies against alpha1-adrenergic receptor subtypes lack specificity in paraffin-embedded sections of murine tissues. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2014, 387, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, A.; Hanada, M. Noradrenaline contracts rat retinal arterioles via stimulation of alpha(1a)- and alpha(1d)-adrenoceptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 673, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, A. Effects of norepinephrine, angiotensin, dihydroergotamine, papaverine, isoproterenol, histamine, nicotinic acid, and xanthinol nicotinate on retinal oxygen tension in cats. Acta Ophthalmol. (Copenh) 1972, 50, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollery, C.T.; Hill, D.W. The response of normal retinal blood vessels to angiotensin and noradrenaline. J. Physiol. 1963, 165, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polak, K.; Dorner, G. Evaluation of the zeiss retinal vessel analyser. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2000, 84, 1285–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jandrasits, K.; Luksch, A. Effect of noradrenaline on retinal blood flow in healthy subjects. Ophthalmology 2002, 109, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garhöfer, G.; Schmetterer, L. Endothelial and adrenergic control. In Ocular Blood Flow; Schmetterer, L., Kiel, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 311–346. [Google Scholar]

- Hara, H.; Ichikawa, M. Bunazosin, a selective alpha1-adrenoceptor antagonist, as an anti-glaucoma drug: Effects on ocular circulation and retinal neuronal damage. Cardiovasc. Drug Rev. 2005, 23, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, P.J.; Nyborg, N.C. Adrenergic responses in isolated bovine retinal resistance arteries. Int. Ophthalmol. 1989, 13, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, D.Y.; Alder, V.A. Vasoactivity of intraluminal and extraluminal agonists in perfused retinal arteries. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1994, 35, 4087–4099. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spada, C.S.; Nieves, A.L. Differential effects of alpha-adrenoceptor agonists on human retinal microvessel diameter. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 17, 255–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoste, A.M.; Boels, P.J. Effect of alpha-1 and beta agonists on contraction of bovine retinal resistance arteries in vitro. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1989, 30, 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hoste, A.M.; Boels, P.J. Effects of beta-antagonists on contraction of bovine retinal microarteries in vitro. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1990, 31, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar]

- Sercombe, R.; Verrecchia, C. Pial artery responses to norepinephrine potentiated by endothelium removal. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1985, 5, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauknight, G.C., Jr.; Faraci, F.M. Endothelium-derived relaxing factor modulates noradrenergic constriction of cerebral arterioles in rabbits. Stroke 1992, 23, 1522–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrier, G.O.; White, R.E. Enhancement of alpha-1 and alpha-2 adrenergic agonist-induced vasoconstriction by removal of endothelium in rat aorta. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1985, 232, 682–687. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lues, I.; Schumann, H.J. Effect of removing the endothelial cells on the reactivity of rat aortic segments to different alpha-adrenoceptor agonists. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1984, 328, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godfraind, T.; Egleme, C. Role of endothelium in the contractile response of rat aorta to alpha-adrenoceptor agonists. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 1985, 68 (Suppl. 10), 65s–71s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egleme, C.; Godfraind, T. Enhanced responsiveness of rat isolated aorta to clonidine after removal of the endothelial cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1984, 81, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alosachie, I.; Godfraind, T. The modulatory role of vascular endothelium in the interaction of agonists and antagonists with alpha-adrenoceptors in the rat aorta. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1988, 95, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furchgott, R.F. The role of endothelium in the responses of vascular smooth muscle to drugs. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1984, 24, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, V.M.; Vanhoutte, P.M. Role of the endothelium in modulating vascular adrenergic receptor actions. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 1989, 286, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- White, R.E.; Carrier, G.O. Alpha 1- and alpha 2-adrenoceptor agonist-induced contraction in rat mesenteric artery upon removal of endothelium. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1986, 122, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrecchia, C.; Sercombe, R. Influence of endothelium on noradrenaline-induced vasoconstriction in rabbit central ear artery. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1985, 12, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.J.; DeFily, D.V. Endothelium-dependent relaxation competes with alpha 1- and alpha 2-adrenergic constriction in the canine epicardial coronary microcirculation. Circulation 1993, 87, 1264–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkenboom, G.; Unger, P. Endothelium-derived relaxing factor and protection against contraction to norepinephrine in isolated canine and human coronary arteries. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1991, 17 (Suppl. 3), S127–S132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocks, T.M.; Angus, J.A. Endothelium-dependent relaxation of coronary arteries by noradrenaline and serotonin. Nature 1983, 305, 627–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgart, D.; Haude, M. Augmented alpha-adrenergic constriction of atherosclerotic human coronary arteries. Circulation 1999, 99, 2090–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vita, J.A.; Treasure, C.B. Patients with evidence of coronary endothelial dysfunction as assessed by acetylcholine infusion demonstrate marked increase in sensitivity to constrictor effects of catecholamines. Circulation 1992, 85, 1390–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heusch, G.; Baumgart, D. Alpha-adrenergic coronary vasoconstriction and myocardial ischemia in humans. Circulation 2000, 101, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmetterer, L.; Polak, K. Role of nitric oxide in the control of ocular blood flow. Prog. Retin. Eye. Res. 2001, 20, 823–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zembowicz, A.; Hecker, M. Nitric oxide and another potent vasodilator are formed from ng-hydroxy-l-arginine by cultured endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 11172–11176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncada, S.; Higgs, E.A. Nitric oxide and the vascular endothelium. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2006, 213–254. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, R.M.; Ashton, D.S. Vascular endothelial cells synthesize nitric oxide from l-arginine. Nature 1988, 333, 664–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, R.M.; Ferrige, A.G. Nitric oxide release accounts for the biological activity of endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Nature 1987, 327, 524–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ignarro, L.J.; Byrns, R.E. Pharmacological evidence that endothelium-derived relaxing factor is nitric oxide: Use of pyrogallol and superoxide dismutase to study endothelium-dependent and nitric oxide-elicited vascular smooth muscle relaxation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1988, 244, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Koss, M.C. Functional role of nitric oxide in regulation of ocular blood flow. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999, 374, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Huang, A. Nitric oxide-mediated arteriolar dilation after endothelial deformation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2001, 280, H714–H721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfamariam, B.; Cohen, R.A. Inhibition of adrenergic vasoconstriction by endothelial cell shear stress. Circ. Res. 1988, 63, 720–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, K.; Sunano, S. Involvement of alpha-adrenoceptors in the endothelium-dependent depression of noradrenaline-induced contraction in rat aorta. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993, 240, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, S.; Parenti, A. Alpha(1d)-adrenoceptors cause endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in the rat mesenteric vascular bed. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001, 296, 869–875. [Google Scholar]

- Angus, J.A.; Cocks, T.M. The alpha adrenoceptors on endothelial cells. Fed. Proc. 1986, 45, 2355–2359. [Google Scholar]

- de Andrade, C.R.; Fukada, S.Y. Alpha1d-adrenoceptor-induced relaxation on rat carotid artery is impaired during the endothelial dysfunction evoked in the early stages of hyperhomocysteinemia. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 543, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipolla, M.J.; Harker, C.T. Endothelial function and adrenergic reactivity in human type-ii diabetic resistance arteries. J. Vasc. Surg. 1996, 23, 940–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, T.; Kaneko, Y. Attenuation of nitric oxide- and prostaglandin-independent vasodilation of retinal arterioles induced by acetylcholine in streptozotocin-treated rats. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2007, 46, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resch, H.; Garhofer, G. Endothelial dysfunction in glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009, 87, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto, W.; Oku, H. Amelioration by topical bunazosin hydrochloride of the impairment in ocular blood flow caused by nitric oxide synthase inhibition in rabbits. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003, 19, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.J.; Minneman, K.P. Recent progress in alpha1-adrenergic receptor research. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2005, 26, 1281–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, H.; Minneman, K.P. Alpha1-adrenoceptor subtypes. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999, 375, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gericke, A.; Kordasz, M.L. Functional role of alpha1-adrenoceptor subtypes in murine ophthalmic arteries. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 4795–4799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docherty, J.R. Subtypes of functional alpha1-adrenoceptor. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2010, 67, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Li, J. Subtypes of alpha 1-adrenoceptors in rat blood vessels. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1990, 190, 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, H.; Peri, K.G. Distribution of alpha1-adrenoceptor subtype proteins in different tissues of neonatal and adult rats. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2000, 78, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piascik, M.T.; Guarino, R.D. The specific contribution of the novel alpha-1d adrenoceptor to the contraction of vascular smooth muscle. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995, 275, 1583–1589. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Reese, J. Murine alpha1-adrenoceptor subtypes. I. Radioligand binding studies. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998, 286, 841–847. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Verfurth, F. Is alpha1d-adrenoceptor protein detectable in rat tissues? Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1997, 355, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hague, C.; Chen, Z. Alpha(1)-adrenergic receptor subtypes: Non-identical triplets with different dancing partners? Life Sci. 2003, 74, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Cabrera, P.J.; Gaivin, R.J. Genetic profiling of alpha 1-adrenergic receptor subtypes by oligonucleotide microarrays: Coupling to interleukin-6 secretion but differences in stat3 phosphorylation and gp-130. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003, 63, 1104–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hein, P.; Michel, M.C. Signal transduction and regulation: Are all alpha1-adrenergic receptor subtypes created equal? Biochem. Pharmacol. 2007, 73, 1097–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborne, N.N. Binding of (-)[3h]noradrenaline to bovine membrane of the retina. Evidence for the existence of alpha 2-receptors. Vis. Res. 1982, 22, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convents, A.; De Backer, J.P. Characterization of alpha 2-adrenergic receptors of calf retina membranes by [3h]-rauwolscine and [3h]-rx 781094 binding. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1987, 36, 2497–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, T.; Cynader, M.S. Localization of alpha-2 adrenergic receptors in the human eye. Ophthalmic Res. 1992, 24, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.K.; Angelo, D.D. Pharmacological characterization of rat alpha 2-adrenergic receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 1991, 40, 407. [Google Scholar]

- Venkataraman, V.; Duda, T. Molecular and pharmacological identity of the α2d-adrenergic receptor subtype in bovine retina and its photoreceptors. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1996, 159, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bylund, D.B. Adrenoceptors; IUPHAR Media: London, UK, 1998; pp. 58–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kalapesi, F.B.; Coroneo, M.T. Human ganglion cells express the alpha-2 adrenergic receptor: Relevance to neuroprotection. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2005, 89, 758–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldemussie, E.; Wijono, M. Localization of alpha 2 receptors in ocular tissues. Vis. Neurosci. 2007, 24, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, L.A.; Gil, D.W. Role of alpha-2 adrenergic receptors in neuroprotection and glaucoma. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2001, 45, S290–S294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilsbach, R.; Hein, L. Are the pharmacology and physiology of α2adrenoceptors determined by α2-heteroreceptors and autoreceptors respectively? Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 165, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, C.; Steinberg, G.K. Neuroprotection by the alpha 2-adrenoreceptor agonist dexmedetomidine in a focal model of cerebral ischemia. Anesthesiology 1993, 79, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Rajakumaraswamy, N. Alpha2-adrenoceptor agonists: Shedding light on neuroprotection? Br. Med. Bull. 2004, 71, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.-J.; Guo, Y. Α2 adrenergic modulation of nmda receptor function as a major mechanism of rgc protection in experimental glaucoma and retinal excitotoxicity. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008, 49, 4515–4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donello, J.E.; Padillo, E.U. Alpha(2)-adrenoceptor agonists inhibit vitreal glutamate and aspartate accumulation and preserve retinal function after transient ischemia. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001, 296, 216–223. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Sanz, M.; Lafuente, M.a.P. Retinal ganglion cell death induced by retinal ischemia: Neuroprotective effects of two alpha-2 agonists. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2001, 45, S261–S267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WoldeMussie, E.; Ruiz, G. Neuroprotection of retinal ganglion cells by brimonidine in rats with laser-induced chronic ocular hypertension. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis.Sci. 2001, 42, 2849–2855. [Google Scholar]

- Katsimpris, J.M.; Siganos, D. Efficacy of brimonidine 0.2% in controlling acute postoperative intraocular pressure elevation after phacoemulsification. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 2003, 29, 2288–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenfield, D.S.; Liebmann, J.M. Brimonidine: A new alpha2-adrenoreceptor agonist for glaucoma treatment. J. Glaucoma 1997, 6, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reitsamer, H.A.; Posey, M. Effects of a topical alpha2 adrenergic agonist on ciliary blood flow and aqueous production in rabbits. Exp. Eye Res. 2006, 82, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, D.W.; Hosking, S.L. Contrast sensitivity improves after brimonidine therapy in primary open angle glaucoma: A case for neuroprotection. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2003, 87, 1463–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, M.S.; Kim, K.Y.; Ju, W.K. Role of cyclic amp in the eye with glaucoma. BMB Rep. 2017, 50, 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Krupin, T.; Liebmann, J.M. A randomized trial of brimonidine versus timolol in preserving visual function: Results from the low-pressure glaucoma treatment study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2011, 151, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Chang, Y.I. Alteration of retinal intrinsic survival signal and effect of alpha2-adrenergic receptor agonist in the retina of the chronic ocular hypertension rat. Vis. Neurosci. 2007, 24, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.J.; Guo, Y. Alpha2 adrenergic receptor-mediated modulation of cytosolic ca++ signals at the inner plexiform layer of the rat retina. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007, 48, 1410–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Wu, S.M. Nmda-evoked [ca2+]i increase in salamander retinal ganglion cells: Modulation by pka and adrenergic receptors. Vis. Neurosci. 2002, 19, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, T. Brimonidine enhances inhibitory postsynaptic activity of off- and on-type retinal ganglion cells in a wistar rat chronic glaucoma model. Exp. Eye Res. 2019, 189, 107833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, R.; Cheng, T. Alpha 2-adrenergic agonists induce basic fibroblast growth factor expression in photoreceptors in vivo and ameliorate light damage. J. Neurosci. 1996, 16, 5986–5992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, Y.; Sato, A. Brimonidine promotes axon growth after optic nerve injury through erk phosphorylation. Cell Death Dis. 2013, 4, e763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Yang, S. Modulation of α-adrenoceptor signalling protects photoreceptors after retinal detachment by inhibiting oxidative stress and inflammation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 801–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Namekata, K. Brimonidine suppresses loss of retinal neurons and visual function in a murine model of optic neuritis. Neurosci. Lett. 2015, 592, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikberg-Matsson, A.; Simonsen, U. Potent α2a-adrenoceptor–mediated vasoconstriction by brimonidine in porcine ciliary arteries. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2001, 42, 2049–2055. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, S.; Kolodjaschna, J. Effect of the α2-adrenoceptor antagonist yohimbine on vascular regulation of the middle cerebral artery and the ophthalmic artery in healthy subjects. Microvasc. Res. 2011, 81, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigert, G.; Resch, H. Intravenous administration of clonidine reduces intraocular pressure and alters ocular blood flow. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 91, 1354–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elena, P.-P.; Denis, P. Beta adrenergic binding sites in the human eye: An autoradiographic study. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 1990, 6, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]