Exercise as a Therapeutic Strategy for Sarcopenia in Heart Failure: Insights into Underlying Mechanisms

Abstract

1. Introduction

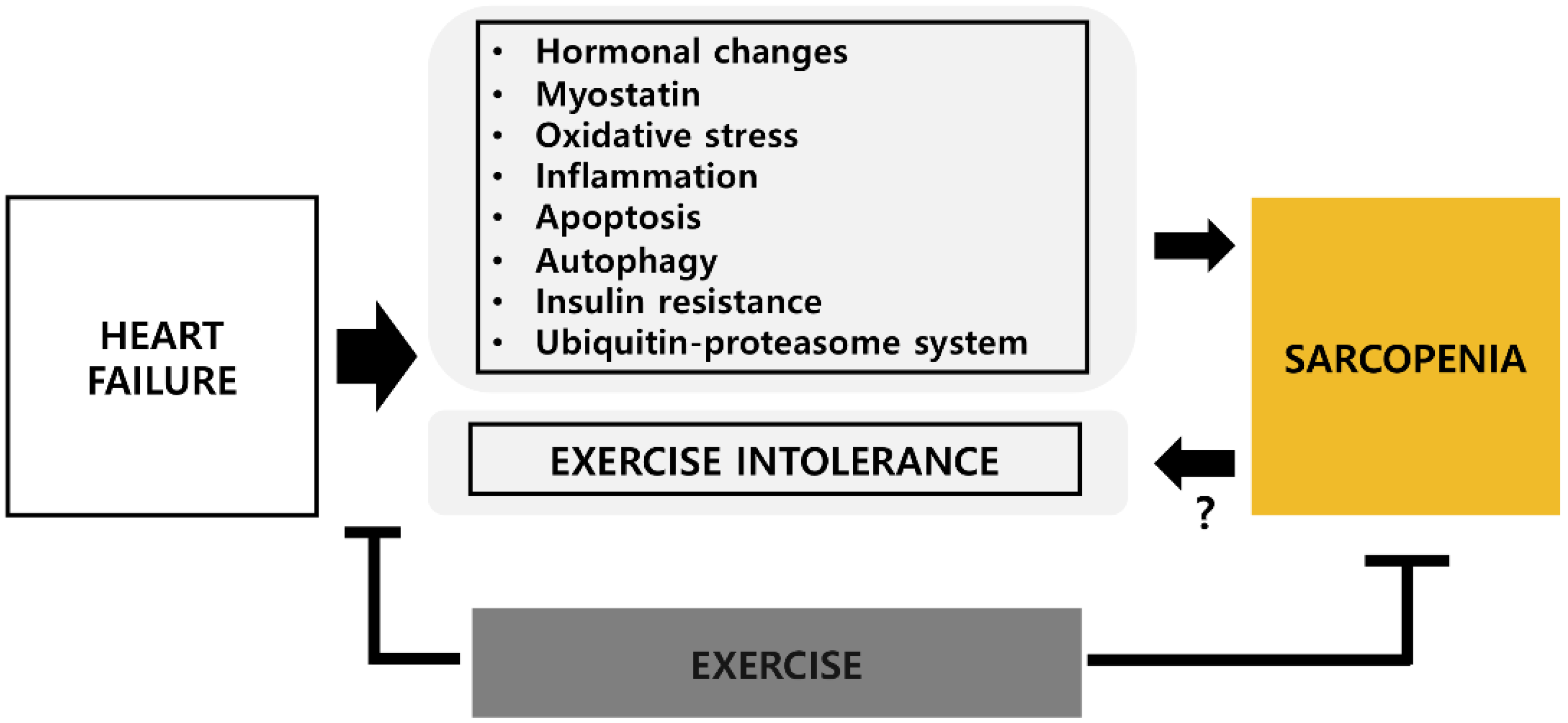

2. Potential Mechanisms of Sarcopenia in Heart Failure

2.1. Hormonal Changes

2.2. Myostatin

2.3. Oxidative Stress

2.4. Inflammation

2.5. Apoptosis

2.6. Autophagy

2.7. Ubiquitin-Proteasome System

2.8. Insulin Resistance

3. Exercise Intolerance and Sarcopenia in HF

4. Effects of Exercise on HF-Related Sarcopenia

4.1. Physical Activity

4.2. Exercise Training

4.2.1. Aerobic Exercise Training

4.2.2. Resistance Exercise Training

4.2.3. Combined Exercise Training

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roger, V.L. Epidemiology of Heart Failure. Circ. Res. 2013, 113, 646–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunwald, E. Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2013, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponikowski, P.; Voors, A.A.; Anker, S.D.; Bueno, H.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Coats, A.J.S.; Falk, V.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; Harjola, V.-P.; Jankowska, E.A.; et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 2129–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, W.J.; Haykowsky, M.J.; Seo, Y.; Stehling, E.; Forman, D.E. Impaired Exercise Tolerance in Heart Failure: Role of Skeletal Muscle Morphology and Function. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2018, 15, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekfani, T.; Pellicori, P.; Morris, D.A.; Ebner, N.; Valentova, M.; Steinbeck, L.; Wachter, R.; Elsner, S.; Sliziuk, V.; Schefold, J.C.; et al. Sarcopenia in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Impact on muscle strength, exercise capacity and quality of life. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 222, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2018, 48, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunjes, D.L.; Kennel, P.J.; Schulze, P.C. Exercise capacity, physical activity, and morbidity. Heart Fail. Rev. 2017, 22, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, A.; Saitoh, M.; Valentova, M.; Sandek, A.; Evertz, R.; Ebner, N.; Loncar, G.; Springer, J.; Doehner, W.; Lainscak, M.; et al. Comparison of sarcopenia and cachexia in men with chronic heart failure: Results from the Studies Investigating Co-morbidities Aggravating Heart Failure (SICA-HF). Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2018, 20, 1580–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fülster, S.; Tacke, M.; Sandek, A.; Ebner, N.; Tschöpe, C.; Doehner, W.; Anker, S.D.; Von Haehling, S. Muscle wasting in patients with chronic heart failure: Results from the studies investigating co-morbidities aggravating heart failure (SICA-HF). Eur. Heart J. 2012, 34, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haykowsky, M.J.; Brubaker, P.H.; Morgan, T.M.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Eggebeen, J.; Kitzman, D.W. Impaired Aerobic Capacity and Physical Functional Performance in Older Heart Failure Patients with Preserved Ejection Fraction: Role of Lean Body Mass. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2013, 68, 968–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narumi, T.; Watanabe, T.; Kadowaki, S.; Takahashi, T.; Yokoyama, M.; Kinoshita, D.; Honda, Y.; Funayama, A.; Nishiyama, S.; Takahashi, H.; et al. Sarcopenia evaluated by fat-free mass index is an important prognostic factor in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2015, 26, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, J.; Springer, J.-I.; Anker, S.D. Muscle wasting and sarcopenia in heart failure and beyond: Update 2017. ESC Heart Fail. 2017, 4, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.-Z.; No, M.-H.; Heo, J.-W.; Park, D.-H.; Kang, J.-H.; Kim, S.H.; Kwak, H.-B. Role of exercise in age-related sarcopenia. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2018, 14, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collamati, A.; Marzetti, E.; Calvani, R.; Tosato, M.; D’Angelo, E.; Sisto, A.N.; Landi, F. Sarcopenia in heart failure: Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2016, 13, 615–624. [Google Scholar]

- Saccà, L. Growth hormone: A newcomer in cardiovascular medicine. Cardiovasc. Res. 1997, 36, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cittadini, A.; Marra, A.M.; Arcopinto, M.; Bobbio, E.; Salzano, A.; Sirico, D.; Napoli, R.; Colao, A.; Longobardi, S.; Baliga, R.R.; et al. Growth Hormone Replacement Delays the Progression of Chronic Heart Failure Combined with Growth Hormone Deficiency: An Extension of a Randomized Controlled Single-Blind Study. JACC Heart Fail. 2013, 1, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezus, E.; Burlui, M.A.; Cardoneanu, A.; Rezus, C.; Codreanu, C.; Pârvu, M.; Rusu-Zota, G.; Tamba, B.I. Inactivity and Skeletal Muscle Metabolism: A Vicious Cycle in Old Age. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brioche, T.; Kireev, R.A.; Cuesta, S.; Gratas-Delamarche, A.; Tresguerres, J.A.; Gómez-Cabrera, M.C.; Viña, J. Growth Hormone Replacement Therapy Prevents Sarcopenia by a Dual Mechanism: Improvement of Protein Balance and of Antioxidant Defenses. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2013, 69, 1186–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, F.; Röhrig, G.; Von Haehling, S.; Traish, A. Testosterone Deficiency and Testosterone Treatment in Older Men. Gerontology 2016, 63, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storer, T.W.; Basaria, S.; Traustadottir, T.; Harman, S.M.; Pencina, K.; Li, Z.; Travison, T.G.; Miciek, R.; Tsitouras, P.; Hally, K.; et al. Effects of Testosterone Supplementation for 3-Years on Muscle Performance and Physical Function in Older Men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 102, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehr, E.; Pilz, S.; Boehm, B.O.; März, W.; Grammer, T.; Obermayer-Pietsch, B. Low free testosterone is associated with heart failure mortality in older men referred for coronary angiography. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2011, 13, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, E.A.; Biel, B.; Majda, J.; Szklarska, A.; Lopuszanska, M.; Medras, M.; Anker, S.D.; Banasiak, W.; Poole-Wilson, P.A.; Ponikowski, P. Anabolic Deficiency in Men with Chronic Heart Failure. Circulation 2006, 114, 1829–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, E.A.; Filippatos, G.; Ponikowska, B.; Borodulin-Nadzieja, L.; Anker, S.D.; Banasiak, W.; Poole-Wilson, P.A.; Ponikowski, P. Reduction in Circulating Testosterone Relates to Exercise Capacity in Men with Chronic Heart Failure. J. Card. Fail. 2009, 15, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherron, A.C.; Lawler, A.M.; Lee, S.-J. Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-p superfamily member. Nature 1997, 387, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendias, C.L.; Kayupov, E.; Bradley, J.R.; Brooks, S.V.; Claflin, D.R. Decreased specific force and power production of muscle fibers from myostatin-deficient mice are associated with a suppression of protein degradation. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011, 111, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruson, D.; Ahn, S.A.; Ketelslegers, J.-M.; Rousseau, M.F. Increased plasma myostatin in heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2011, 13, 734–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenk, K.; Erbs, S.; Höllriegel, R.; Beck, E.; Linke, A.; Gielen, S.; Winkler, S.M.; Sandri, M.; Hambrecht, R.; Schuler, G.; et al. Exercise training leads to a reduction of elevated myostatin levels in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2011, 19, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyuna, L.A.; E Albuquerque, R.P.; Chen, C.-H.; Mochly-Rosen, D.; Ferreira, J.C.B. Targeting mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in heart failure: Challenges and opportunities. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 129, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libera, L.; Zennaro, R.; Sandri, M.; Ambrosio, G.B.; Vescovo, G. Apoptosis and atrophy in rat slow skeletal muscles in chronic heart failure. Am. J. Physiol. Content 1999, 277, C982–C986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirakawa, R.; Yokota, T.; Nakajima, T.; Takada, S.; Yamane, M.; Furihata, T.; Maekawa, S.; Nambu, H.; Katayama, T.; Fukushima, A.; et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation in blood cells is associated with disease severity and exercise intolerance in heart failure patients. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dröge, W. Redox regulation in anabolic and catabolic processes. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2006, 9, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymes, C.; Bendall, J.K.; Ratajczak, P.; Cave, A.C.; Samuel, J.-L.; Hasenfuss, G.; Shah, A.M. Increased myocardial NADPH oxidase activity in human heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 41, 2164–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-M.; Gall, N.P.; Grieve, D.J.; Chen, M.; Shah, A.M. Activation of NADPH Oxidase During Progression of Cardiac Hypertrophy to Failure. Hypertension 2002, 40, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechara, L.R.; Moreira, J.B.; Jannig, P.R.; Voltarelli, V.A.; Dourado, P.M.; Vasconcelos, A.R.; Scavone, C.; Ramires, P.R.; Brum, P.C. NADPH oxidase hyperactivity induces plantaris atrophy in heart failure rats. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014, 175, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, B.; Kalman, J.; Mayer, L.; Fillit, H.M.; Packer, M. Elevated Circulating Levels of Tumor Necrosis Factor in Severe Chronic Heart Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990, 323, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, M.; Bowen, T.S.; Rolim, N.; Dieterlen, M.-T.; Werner, S.; Hoshi, T.; Fischer, T.; Mangner, N.; Linke, A.; Schuler, G.; et al. Skeletal Muscle Alterations Are Exacerbated in Heart Failure with Reduced Compared with Preserved Ejection Fraction: Mediated by circulating cytokines? Circ. Heart Fail. 2016, 9, e003027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briasoulis, A.; Androulakis, E.; Christophides, T.; Tousoulis, D. The role of inflammation and cell death in the pathogenesis, progression and treatment of heart failure. Heart Fail. Rev. 2016, 21, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaap, L.A.; Pluijm, S.M.; Deeg, D.J.; Visser, M. Inflammatory Markers and Loss of Muscle Mass (Sarcopenia) and Strength. Am. J. Med. 2006, 119, 526.e9–526.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttridge, D.C.; Mayo, M.W.; Madrid, L.V.; Wang, C.-Y.; Baldwin, A.S., Jr. NF-κB-Induced Loss of MyoD Messenger RNA: Possible Role in Muscle Decay and Cachexia. Science 2000, 289, 2363–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaloor, D.; Miller, K.J.; Gephart, J.; Mitchell, P.O.; Pavlath, G.K. Systemic administration of the NF-κB inhibitor curcumin stimulates muscle regeneration after traumatic injury. Am. J. Physiol. 1999, 277, C320–C329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, N.; Herbst, A.; McKenzie, D.; Aiken, J.M. Apoptosis and necrosis mediate skeletal muscle fiber loss in age-induced mitochondrial enzymatic abnormalities. Aging Cell 2015, 14, 1085–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Wang, X.; Miereles, C.; Bailey, J.L.; Debigare, R.; Zheng, B.; Price, S.R.; Mitch, W.E. Activation of caspase-3 is an initial step triggering accelerated muscle proteolysis in catabolic conditions. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 113, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, V.; Jiang, H.; Yu, J.; Möbius-Winkler, S.; Fiehn, E.; Linke, A.; Weigl, C.; Schuler, G.; Hambrecht, R. Apoptosis in skeletal myocytes of patients with chronic heart failure is associated with exercise intolerance. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1999, 33, 959–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Kou, X.; Jia, S.; Yang, X.; Yang, Y.; Chen, N. Autophagy as a Potential Target for Sarcopenia. J. Cell. Physiol. 2015, 231, 1450–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meyer, G.R.Y.; De Keulenaer, G.W.; Martinet, W. Role of autophagy in heart failure associated with aging. Heart Fail. Rev. 2010, 15, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannig, P.R.; Moreira, J.B.N.; Bechara, L.R.G.; Bozi, L.H.M.; Bacurau, A.V.; Monteiro, A.W.A.; Dourado, P.M.; Wisløff, U.; Brum, P.C. Autophagy Signaling in Skeletal Muscle of Infarcted Rats. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, N.; Fujino, H.; Sakamoto, H.; Takegaki, J.; Deie, M. Time course of ubiquitin-proteasome and macroautophagy-lysosome pathways in skeletal muscle in rats with heart failure. Biomed. Res. 2015, 36, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bowen, T.S.; Herz, C.; Rolim, N.P.; Berre, A.-M.O.; Halle, M.; Kricke, A.; Linke, A.; Da Silva, G.J.; Wisloff, U.; Adams, V. Effects of Endurance Training on Detrimental Structural, Cellular, and Functional Alterations in Skeletal Muscles of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. J. Card. Fail. 2018, 24, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumucio, J.P.; Mendias, C.L. Atrogin-1, MuRF-1, and sarcopenia. Endocrine 2012, 43, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangner, N.; Weikert, B.; Bowen, T.S.; Sandri, M.; Höllriegel, R.; Erbs, S.; Hambrecht, R.; Schuler, G.; Linke, A.; Gielen, S.; et al. Skeletal muscle alterations in chronic heart failure: Differential effects on quadriceps and diaphragm. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2015, 6, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikanthan, P.; Hevener, A.L.; Karlamangla, A.S. Sarcopenia Exacerbates Obesity-Associated Insulin Resistance and Dysglycemia: Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doehner, W.; Gathercole, D.; Cicoira, M.; Krack, A.; Coats, A.J.; Camici, P.G.; Anker, S.D. Reduced glucose transporter GLUT4 in skeletal muscle predicts insulin resistance in non-diabetic chronic heart failure patients independently of body composition. Int. J. Cardiol. 2010, 138, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doehner, W.; Von Haehling, S.; Anker, S.D. Protective overweight in cardiovascular disease: Moving from ‘paradox’ to ‘paradigm’. Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 2729–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandri, M.; Barberi, L.; Bijlsma, A.Y.; Blaauw, B.; Dyar, K.A.; Milan, G.; Mammucari, C.; Meskers, C.G.M.; Pallafacchina, G.; Paoli, A.; et al. Signalling pathways regulating muscle mass in ageing skeletal muscle. The role of the IGF1-Akt-mTOR-FoxO pathway. Biogerontology 2013, 14, 303–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marburger, C.; Brubaker, P.; Pollock, W.; Morgan, T.; Kitzman, D. Reproducibility of cardiopulmonary exercise testing in elderly patients with congestive heart failure. Am. J. Cardiol. 1998, 82, 905–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensimhon, D.R.; Leifer, E.S.; Ellis, S.J.; Fleg, J.L.; Keteyian, S.J.; Piña, I.L.; Kitzman, D.W.; McKelvie, R.S.; Kraus, W.E.; Forman, D.E.; et al. Reproducibility of Peak Oxygen Uptake and Other Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing Parameters in Patients with Heart Failure (from the Heart Failure and A Controlled Trial Investigating Outcomes of exercise traiNing). Am. J. Cardiol. 2008, 102, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Toda, N.; Okamura, T. Obesity impairs vasodilatation and blood flow increase mediated by endothelial nitric oxide: An overview. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 53, 1228–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemeijer, V.M.; Snijders, T.; Verdijk, L.B.; Van Kranenburg, J.; Groen, B.B.L.; Holwerda, A.M.; Spee, R.F.; Wijn, P.F.F.; Van Loon, L.J.C.; Kemps, H.M.C. Skeletal muscle fiber characteristics in patients with chronic heart failure: Impact of disease severity and relation with muscle oxygenation during exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 2018, 125, 1266–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisaka, T.; Stringer, W.W.; Koike, A.; Agostoni, P.; Wasserman, K. Mechanisms That Modulate Peripheral Oxygen Delivery during Exercise in Heart Failure. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2017, 14, S40–S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rullman, E.; Melin, M.; Mandić, M.; Gonon, A.; Fernandez-Gonzalo, R.; Gustafsson, T. Circulatory factors associated with function and prognosis in patients with severe heart failure. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2019, 109, 655–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, S.D.; Ponikowski, P.; Varney, S.; Chua, T.P.; Clark, A.L.; Webb-Peploe, K.M.; Harrington, D.; Kox, W.J.; A Poole-Wilson, P.; Coats, A.J. Wasting as independent risk factor for mortality in chronic heart failure. Lancet 1997, 349, 1050–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, D.N.; Le, K.U.; Ridout, S.J. Age and regional specificity of peak limb vascular conductance in men. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 98, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prior, S.J.; Ryan, A.S.; Blumenthal, J.B.; Watson, J.M.; Katzel, L.I.; Goldberg, A.P. Sarcopenia Is Associated with Lower Skeletal Muscle Capillarization and Exercise Capacity in Older Adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med Sci. 2016, 71, 1096–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, K.; Schär, M.; Panjrath, G.S.; Zhang, Y.; Sharma, K.; Bottomley, P.A.; Golozar, A.; Steinberg, A.; Gerstenblith, G.; Russell, S.D.; et al. Fatigability, Exercise Intolerance, and Abnormal Skeletal Muscle Energetics in Heart Failure. Circ. Heart Fail. 2017, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, S.A.; Minson, C.T.; Halliwill, J.R. The cardiovascular system after exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 122, 925–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, V.; Linke, A. Impact of exercise training on cardiovascular disease and risk. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2019, 1865, 728–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharman, J.E.; La Gerche, A.; Coombes, J.S. Exercise and Cardiovascular Risk in Patients with Hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 2014, 28, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillard, F.; Laoudj-Chenivesse, D.; Carnac, G.; Mercier, J.; Rami, J.; Riviere, D.; Rolland, Y. Physical Activity and Sarcopenia. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2011, 27, 449–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wannamethee, S.G.; Shaper, A.G. Physical Activity in the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. Sports Med. 2001, 31, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbab-Zadeh, A.; Dijk, E.; Prasad, A.; Fu, Q.; Torres, P.; Zhang, R.; Thomas, J.D.; Palmer, D.; Levine, B.D. Effect of Aging and Physical Activity on Left Ventricular Compliance. Circulation 2004, 110, 1799–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraigher-Krainer, E.; Lyass, A.; Massaro, J.M.; Lee, U.S.; Ho, J.E.; Levy, D.; Kannel, W.B.; Vasan, R.S. Association of physical activity and heart failure with preserved vs. reduced ejection fraction in the elderly: The Framingham Heart Study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2013, 15, 742–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.R.; Correa, B.D.; Pereira, C.G.D.S.; Gobbo, L.A. Physical Activity Decreases the Risk of Sarcopenia and Sarcopenic Obesity in Older Adults with the Incidence of Clinical Factors: 24-Month Prospective Study. Exp. Aging Res. 2020, 46, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helgerud, J.; Høydal, K.; Wang, E.; Karlsen, T.; Berg, P.; Bjerkaas, M.; Simonsen, T.; Helgesen, C.; Hjorth, N.; Bach, R.; et al. Aerobic High-Intensity Intervals Improve VO2max More than Moderate Training. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2007, 39, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lelyavina, T.A.; Galenko, V.L.; Ivanova, O.A.; Komarova, M.Y.; Ignatieva, E.V.; Bortsova, M.A.; Yukina, G.Y.; Khromova, N.V.; Sitnikova, M.Y.; Kostareva, A.; et al. Clinical Response to Personalized Exercise Therapy in Heart Failure Patients with Reduced Ejection Fraction Is Accompanied by Skeletal Muscle Histological Alterations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gielen, S.; Sandri, M.; Kozarez, I.; Kratzsch, J.; Teupser, D.; Thiery, J.; Erbs, S.; Mangner, N.; Lenk, K.; Hambrecht, R.; et al. Exercise Training Attenuates MuRF-1 Expression in the Skeletal Muscle of Patients with Chronic Heart Failure Independent of Age: The randomized Leipzig Exercise Intervention in Chronic Heart Failure and Aging catabolism study. Circulation 2012, 125, 2716–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, T.F.; Bacurau, A.V.N.; Moreira, J.B.N.; Paixão, N.A.; Campos, J.C.; Ferreira, J.C.B.; Leal, M.L.; Negrão, C.E.; Moriscot, A.S.; Wisløff, U.; et al. Exercise Training Prevents Oxidative Stress and Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Overactivity and Reverse Skeletal Muscle Atrophy in Heart Failure. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.D.; Carey, M.F.; Selig, S.; Hayes, A.; Krum, H.; Patterson, J.; Toia, D.; Hare, D.L. Circuit Resistance Training in Chronic Heart Failure Improves Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial ATP Production Rate—A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Card. Fail. 2007, 13, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, F.; Mathieu-Costello, O.; Wagner, P.D.; Richardson, R.S. Acute and chronic exercise in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: Evidence of structural and functional plasticity and intact angiogenic signalling in skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2018, 596, 5149–5161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, T.F.; Bechara, L.R.G.; Bacurau, A.V.N.; Jannig, P.R.; Voltarelli, V.A.; Dourado, P.M.; Vasconcelos, A.R.; Scavone, C.; Ferreira, J.C.B.; Brum, P.C. Exercise training decreases NADPH oxidase activity and restores skeletal muscle mass in heart failure rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 122, 817–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacurau, A.V.; Jannig, P.R.; De Moraes, W.M.; Cunha, T.F.; Medeiros, A.; Barberi, L.; Coelho, M.A.; Bacurau, R.F.; Ugrinowitsch, C.; Musarò, A.; et al. Akt/mTOR pathway contributes to skeletal muscle anti-atrophic effect of aerobic exercise training in heart failure mice. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 214, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenk, K.; Schur, R.; Linke, A.; Erbs, S.; Matsumoto, Y.; Adams, V.; Schuler, G. Impact of exercise training on myostatin expression in the myocardium and skeletal muscle in a chronic heart failure model. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2009, 11, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, R.W.A.; Piedade, W.P.; Soares, L.C.; Souza, P.A.T.; Aguiar, A.F.; Vechetti-Júnior, I.J.; Campos, D.H.S.; Fernandes, A.A.H.; Okoshi, K.; Carvalho, R.F.; et al. Aerobic Exercise Training Prevents Heart Failure-Induced Skeletal Muscle Atrophy by Anti-Catabolic, but Not Anabolic Actions. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, J.B.N.; Bechara, L.R.G.; Bozi, L.H.M.; Jannig, P.R.; Monteiro, A.W.A.; Dourado, P.M.; Wisløff, U.; Brum, P.C. High- versus moderate-intensity aerobic exercise training effects on skeletal muscle of infarcted rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 2013, 114, 1029–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Jia, D.; Feng, R.; Tian, Z. Effects of different types of exercise on skeletal muscle atrophy, antioxidant capacity and growth factors expression following myocardial infarction. Life Sci. 2018, 213, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, M.J.; Pagan, L.U.; Lima, A.R.R.; Reyes, D.R.A.; Martinez, P.F.; Damatto, F.C.; Pontes, T.H.D.; Rodrigues, E.A.; Souza, L.M.; Tosta, I.F.; et al. Effects of aerobic and resistance exercise on cardiac remodelling and skeletal muscle oxidative stress of infarcted rats. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 5352–5362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavazis, A.N.; Smuder, A.J.; Powers, S.K. Effects of short-term endurance exercise training on acute doxorubicin-induced FoxO transcription in cardiac and skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 2014, 117, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heineke, J.; Auger-Messier, M.; Xu, J.; Sargent, M.; York, A.; Welle, S.; Molkentin, J.D. Genetic Deletion of Myostatin from the Heart Prevents Skeletal Muscle Atrophy in Heart Failure. Circulation 2010, 121, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, M.; Schober-Halper, B.; Oesen, S.; Franzke, B.; Tschan, H.; Bachl, N.; Strasser, E.-M.; Quittan, M.; Wagner, K.-H.; Wessner, B. Effects of elastic band resistance training and nutritional supplementation on muscle quality and circulating muscle growth and degradation factors of institutionalized elderly women: The Vienna Active Ageing Study (VAAS). Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 116, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitbart, A.; Auger-Messier, M.; Molkentin, J.D.; Heineke, J. Myostatin from the heart: Local and systemic actions in cardiac failure and muscle wasting. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2011, 300, H1973–H1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haykowsky, M.J.; Kouba, E.J.; Brubaker, P.H.; Nicklas, B.J.; Eggebeen, J.; Kitzman, D.W. Skeletal Muscle Composition and Its Relation to Exercise Intolerance in Older Patients with Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction. Am. J. Cardiol. 2014, 113, 1211–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, A.J.A.; Bharadwaj, M.S.; Van Horn, C.; Nicklas, B.J.; Lyles, M.F.; Eggebeen, J.; Haykowsky, M.J.; Brubaker, P.H.; Kitzman, D.W. Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Content, Oxidative Capacity, and Mfn2 Expression Are Reduced in Older Patients with Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction and Are Related to Exercise Intolerance. JACC Heart Fail. 2016, 4, 636–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, J.-W.; Yoo, S.-Z.; No, M.-H.; Park, D.-H.; Kang, J.-H.; Kim, T.-W.; Kim, C.-J.; Seo, D.-Y.; Han, J.; Yoon, J.-H.; et al. Exercise Training Attenuates Obesity-Induced Skeletal Muscle Remodeling and Mitochondria-Mediated Apoptosis in the Skeletal Muscle. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, S.-Z.; No, M.-H.; Heo, J.-W.; Park, D.-H.; Kang, J.-H.; Kim, J.-H.; Seo, D.Y.; Han, J.; Jung, S.-J.; Kwak, H.-B. Effects of Acute Exercise on Mitochondrial Function, Dynamics, and Mitophagy in Rat Cardiac and Skeletal Muscles. Int. Neurourol. J. 2019, 23, S22–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandic, S.; Myers, J.; Selig, S.E.; Levinger, I. Resistance Versus Aerobic Exercise Training in Chronic Heart Failure. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2011, 9, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuliano, C.; Karahalios, A.; Neil, C.; Allen, J.D.; Levinger, I. The effects of resistance training on muscle strength, quality of life and aerobic capacity in patients with chronic heart failure—A meta-analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 227, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, T.; Palus, S.; Springer, J. Skeletal muscle wasting in chronic heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 2018, 5, 1099–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovljevic, D.G.; Donovan, G.; Nunan, D.; McDonagh, S.; Trenell, M.I.; Grocott-Mason, R.; Brodie, D.A. The effect of aerobic versus resistance exercise training on peak cardiac power output and physical functional capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. Int. J. Cardiol. 2010, 145, 526–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjarnason-Wehrens, B.; Mayer-Berger, W.; Meister, E.; Baum, K.; Hambrecht, R.; Gielen, S. Recommendations for resistance exercise in cardiac rehabilitation. Recommendations of the German Federation for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Prev. Rehabil. 2004, 11, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Peng, X.; Li, K.; Wu, C.-J. Effects of combined aerobic and resistance training in patients with heart failure: A meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Nurs. Health Sci. 2019, 21, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irving, B.A.; Lanza, I.R.; Henderson, G.C.; Rao, R.R.; Spiegelman, B.M.; Nair, K.S. Combined Training Enhances Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Oxidative Capacity Independent of Age. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 1654–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Study Design | Subjects | Exercise Type | Beneficial Effects of Exercise |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lenk et al. [27] | RCT | Chronic HF patients | Type: aerobic exercise (bicycle ergometer) Duration: 12 weeks Frequency: daily Time: 20–30 min/day | In skeletal muscle ⇓ Catabolic gene expression (Myostatin) In serum ⇔ Myostatin level |

| Lelyavina et al. [74] | RCT | HF patients | Type: aerobic exercise (walking) Duration: 12 weeks Frequency: 4–5 times/week | ⇑ Peak VO2 (mL/kg/min) ⇑ Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) ⇑ Exercise tolerance In skeletal muscle ⇓ Fiber diameter, endomysium thickness |

| Gielen et al. [75] | RCT | Chronic HF patients | Type: aerobic exercise (bicycle ergometer) Duration: 4 weeks Frequency: 4 times/week Time: 20 min/day | ⇑ Peak VO2 (mL/kg/min) In vastus lateralis muscle biopsies ⇓ Catabolic gene expression (MuRF-1) ⇑ Anabolic gene expression (IGF-1) ⇓ Inflammatory gene expression (TNF-) |

| Cunha et al. [76] | RCT | HF patients | Type: aerobic exercise (walking) Duration: 12 weeks Frequency: 3 times/week Time: 50 min/week | ⇑ Peak VO2 (mL/kg/min) In skeletal muscle ⇓ Proteasome activity |

| William et al. [77] | RCT | Chronic HF patients | Type: resistance training (upper and lower body) Duration: 11 weeks Frequency: 3 session/week | ⇑ Peak VO2 (mL/kg/min) ⇑ Lactate threshold (W) ⇑ Peak lactate (mmol/L) ⇑ Capillary density In skeletal muscle ⇑ Oxidative capacity (CS, HAD enzyme activity) ⇑ MAPR (mmol ATP/min/kg) |

| Esposito et al. [78] | RCT | HF patients with reduced ejection fraction | Type: resistance training (knee extensor exercise) Duration: 8 weeks Frequency: 3 times/week | In skeletal muscle ⇑ Type 1 fiber ⇑ Mitochondria volume ⇔ VEGF mRNA |

| Authors | Subjects | Exercise Type | Beneficial Effects of Exercise |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cunha et al. [76] | α2A/α2CARKO mice | Type: Treadmill running Duration: 8 weeks Intensity: moderate intensity Frequency: 5 days/week | ⇑ Exercise performance In plantaris muscle ⇑ Cross area of muscle ⇓ Atrogin-1/MAFbx and E3α mRNA levels |

| Cunha et al. [79] | LAD-ligation rat | Type: Treadmill running Duration: 8 weeks Intensity: Moderate intensity Frequency: 5 days/week | ⇑ Exercise performance ⇑ Type 1 fiber percentage ⇓ Serum TNFα In plantaris muscle ⇓ ROS ⇓ NOX2, p47phox and NADPH oxidase ⇓ NF-kB and p38 MAPK |

| Bacurau et al. [80] | α2A/α2CARKO mice | Type: Treadmill running Duration: 8 weeks Intensity: Moderate intensity Frequency: 5 days/week | ⇑ Exercise performance ⇑ Soleus atrophy In soleus muscle ⇑ IGF-1/Akt/mTOR signaling, ⇓ Proteasome activity (p4E-BP1/4E-BP1, p-p70S6K/p70S6K) |

| Lenk et al. [81] | LAD-ligation rat | Type: Treadmill running Duration: 4 weeks Intensity: 30 m/min Frequency: 5 days/week | In gastrocnemius muscle ⇓ Myostatin expression In muscle cell ⇑ Myostatin via TNFα/p38MAPK/NFkB signaling pathway |

| Souza et al. [82] | Aortic stenosis surgery rat | Type: Treadmill running Duration: 10 weeks Intensity: 15 m/min Frequency: 5 days/week | ⇑ Serum IGF-1 In soleus and plantaris muscle ⇑ Cross area of muscle ⇑ CS activity ⇑ PGC1α ⇓ FOXO1 mRNA |

| Moreira et al. [83] | LAD-ligation rat | Type: Treadmill running Duration: 8 weeks Intensity: moderate intensity (60% VO2max vs. 85% VO2max) Frequency: 5 days/week | ⇑ Exercise performance In soleus muscle ⇑ PDK mRNA ⇑ CS activity ⇑ Glycogen content ⇓ Atrogin-1, MuRF1 mRNA In plantaris muscle ⇑ CS activity ⇑ Glycogen content ⇑ Hexokinase ⇓ Atrogin-1 mRNA |

| Cai et al. [84] | Myocardial infarction surgery rat | Type: Resistance exercise (Ladder climbing) Duration: 3 sessions/day, 4 weeks Intensity: moderate intensity Frequency: 5 days/week | In soleus muscle ⇓ ROS ⇓ Atrogin-1 and MuRF-1 ⇑ IGF-1/Akt/ERK |

| Gomes et al. [85] | LAD-ligation rat | Type: Treadmill running vs. resistance exercise (ladder climbing) Duration: 12 weeks Intensity: moderate intensity Frequency: 3 days/week | Treadmill running ⇑ Maximum exercise capacity Ladder climbing ⇑ Maximum carrying load In gastrocnemius muscle ⇓ Lipid hydroperoxide ⇑ Glutathione peroxidase activity ⇑ Superoxide dismutase activity |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cho, J.; Choi, Y.; Sajgalik, P.; No, M.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Kim, S.; Heo, J.-W.; Cho, E.-J.; Chang, E.; Kang, J.-H.; et al. Exercise as a Therapeutic Strategy for Sarcopenia in Heart Failure: Insights into Underlying Mechanisms. Cells 2020, 9, 2284. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9102284

Cho J, Choi Y, Sajgalik P, No M-H, Lee S-H, Kim S, Heo J-W, Cho E-J, Chang E, Kang J-H, et al. Exercise as a Therapeutic Strategy for Sarcopenia in Heart Failure: Insights into Underlying Mechanisms. Cells. 2020; 9(10):2284. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9102284

Chicago/Turabian StyleCho, Jinkyung, Youngju Choi, Pavol Sajgalik, Mi-Hyun No, Sang-Hyun Lee, Sujin Kim, Jun-Won Heo, Eun-Jeong Cho, Eunwook Chang, Ju-Hee Kang, and et al. 2020. "Exercise as a Therapeutic Strategy for Sarcopenia in Heart Failure: Insights into Underlying Mechanisms" Cells 9, no. 10: 2284. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9102284

APA StyleCho, J., Choi, Y., Sajgalik, P., No, M.-H., Lee, S.-H., Kim, S., Heo, J.-W., Cho, E.-J., Chang, E., Kang, J.-H., Kwak, H.-B., & Park, D.-H. (2020). Exercise as a Therapeutic Strategy for Sarcopenia in Heart Failure: Insights into Underlying Mechanisms. Cells, 9(10), 2284. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9102284