Three-Dimensional Human Liver Micro Organoids and Bone Co-Culture Mimics Alcohol-Induced BMP Dysregulation and Bone Remodeling Defects

Highlights

- The present study established a long-term 3D human liver–bone co-culture model mimicking alcohol-induced hepatic osteodystrophy (HOD) with fibrogenic liver changes and bone defects.

- Chronic 50 mM alcohol triggers hepatic CYP2E1 activation, EMT/fibrosis, BMP imbalance (↓BMP2, ↑BMP13), reduced osteoblast mineralization, and chondrogenic shift in bone progenitors.

- The present study provides an organoid-based platform for studying the liver–bone axis and BMP dysregulation in HOD, surpassing monocultures or animal models.

- The present study enables the screening of BMP-targeted therapies to restore bone homeostasis in alcohol-related chronic liver disease.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Chemical and Reagents

2.3. Preparation and Sterilization of Agarose Plates

2.4. Preparation of Human Platelet-Rich Plasma (hPRP) Scaffolds

2.5. Cell Seeding

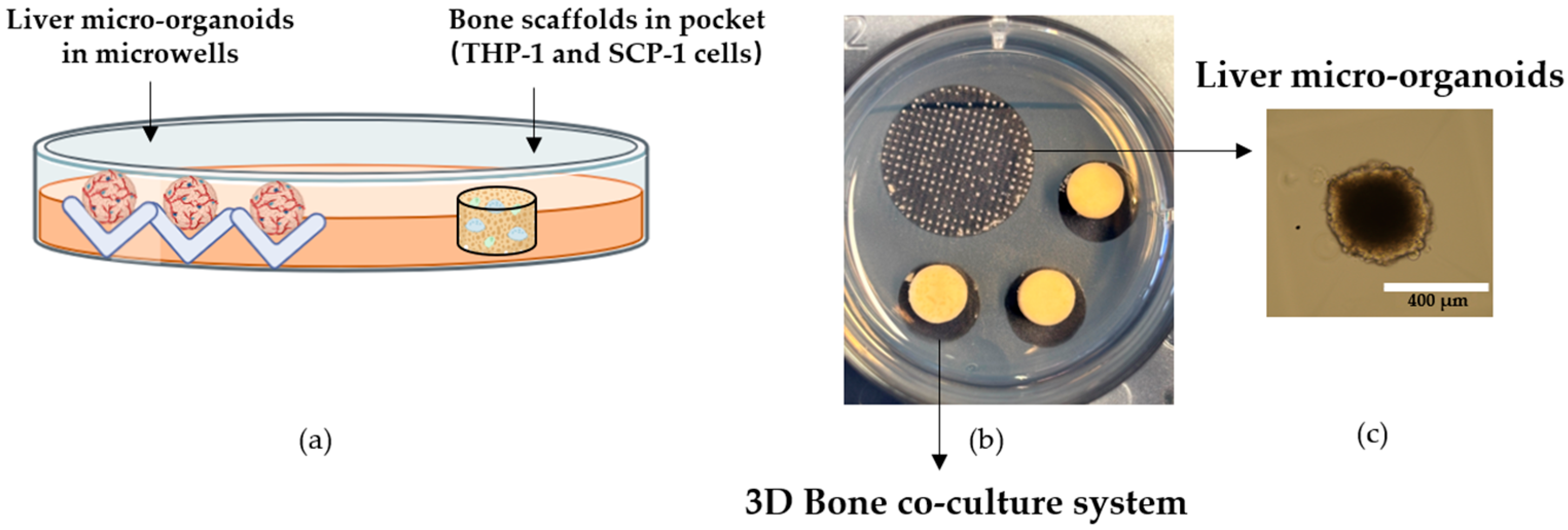

2.5.1. Bone Co-Culture System

2.5.2. Liver Micro-Organoids

2.5.3. Development of 3D Human In Vitro Liver–Bone Co-Culture System

2.5.4. Stimulation of the Liver–Bone System with Alcohol

2.6. Measurement of Mitochondrial Activity

2.7. Measurement of UDP-Glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) Activity (Phase II Enzymes)

2.8. Measurement of Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) Activity

2.9. Measurement of Tartrate-Resistant Acid Phosphatase (TRAP) Activity

2.10. DNA Isolation and Quantification

2.11. Intracellular Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Activity

2.12. Luciferase Reporter Assay

2.13. Semi-Quantitative Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) Analysis

2.14. Dot Blot Analysis

2.15. Western Blot Analysis

2.16. Mineral Content of Bone Scaffold

2.17. Stiffness of Bone Scaffold

2.18. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Long-Term Viability and Functional Maintenance of In Vitro Liver Micro-Organoids for at Least 21 Days

3.2. Induction of Alcohol-Metabolizing Enzyme and Fibrogenic Markers Following Alcohol Exposure in In Vitro Liver Micro-Organoids

3.3. Alcohol Promotes EMT-Regulating Gene Expression, Matrix-Associated Protein Release, and Liver Damage Markers in Liver Micro-Organoids

3.4. Alcohol Does Not Significantly Affect Bone Co-Culture System Function

3.5. Alcohol Exposure Weakens Bone Quality by Inhibiting Mineralization in Liver–Bone Co-Culture System

3.6. Alcohol Exposure Downregulates BMP2 and Upregulates BMP13 in Liver Micro-Organoids

3.7. Hepatic BMPs Trigger Bone BMP Pathway Activation with Downstream Nuclear Signaling

3.8. Alcohol Impairs Osteogenic Differentiation by Downregulating RUNX2 and Modulating Lineage-Associated Transcription Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AP | Alkaline phosphatase |

| ALD | Alcoholic liver disease |

| BMPs | Bone morphogenetic proteins |

| BMCs | Bone mesenchymal stem cells |

| CLD | Chronic liver disease |

| CYPs | Cytochrome p450 |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| FCS | Fetal calf serum |

| HSCs | Hepatic stellate cells |

| HOD | Hepatic osteodystrophy |

| hPRP | Human platelet-rich plasma |

| GLU | Glutamine |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| MMP9 | Matrix metalloproteinase-9 |

| MSCs | Mesenchymal stem cells |

| NTX | N-terminal telopeptide |

| P/S | Penicillin/streptomycin |

| PRP | Platelet-rich plasma |

| TRAP | Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase |

| TNAP | Non-specific alkaline phosphatase |

| UGT | UDP-glucuronosyltransferase |

References

- Ehnert, S.; Aspera-Werz, R.H.; Ruoß, M.; Dooley, S.; Hengstler, J.G.; Nadalin, S.; Relja, B.; Badke, A.; Nussler, A.K. Hepatic Osteodystrophy-Molecular Mechanisms Proposed to Favor Its Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collier, J. Bone disorders in chronic liver disease. Hepatology 2007, 46, 1271–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Shi, T.S.; Shen, S.Y.; Shi, Y.; Gao, H.L.; Wu, J.; Lu, X.; Gao, X.; Ju, H.X.; Wang, W.; et al. Defects in a liver-bone axis contribute to hepatic osteodystrophy disease progression. Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 441–457.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Peng, X.; Li, N.; Gou, L.; Xu, T.; Wang, Y.; Qin, J.; Liang, H.; Ma, P.; Li, S.; et al. Emerging role of liver-bone axis in osteoporosis. J. Orthop. Transl. 2024, 48, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osna, N.A.; Donohue, T.M., Jr.; Kharbanda, K.K. Alcoholic Liver Disease: Pathogenesis and Current Management. Alcohol Res. 2017, 38, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarjuna, D.; Karthikeyan, E. Alcohol-associated liver disease: A review. Gastroenterol. Endosc. 2025, 3, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Alcohol Taxation and Pricing Policies and Their Impact on Alcohol Consumption in Ukraine from 2011–2021: Country Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Information System on Alcohol and Health. Levels of Consumption. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/topic-details/GHO/levels-of-consumption (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Page, A.; Paoli, P.P.; Hill, S.J.; Howarth, R.; Wu, R.; Kweon, S.M.; French, J.; White, S.; Tsukamoto, H.; Mann, D.A.; et al. Alcohol directly stimulates epigenetic modifications in hepatic stellate cells. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patidar, P.; Hirani, N.; Bharti, S.; Baig, M.S. Key regulators of hepatic stellate cell activation in alcohol liver Disease: A comprehensive review. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 141, 112938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, Y.H.; Huang, Y.H.; Chu, T.H.; Chen, C.L.; Lin, P.R.; Huang, S.C.; Wu, D.C.; Huang, C.C.; Hu, T.H.; Kao, Y.H.; et al. BMP-2 restoration aids in recovery from liver fibrosis by attenuating TGF-β1 signaling. Lab. Investig. 2018, 98, 999–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desroches-Castan, A.; Tillet, E.; Ricard, N.; Ouarné, M.; Mallet, C.; Belmudes, L.; Couté, Y.; Boillot, O.; Scoazec, J.Y.; Bailly, S.; et al. Bone Morphogenetic Protein 9 Is a Paracrine Factor Controlling Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cell Fenestration and Protecting Against Hepatic Fibrosis. Hepatology 2019, 70, 1392–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschl, V.; Seitz, T.; Sommer, J.; Thasler, W.; Bosserhoff, A.; Hellerbrand, C. Bone morphogenetic protein 13 in hepatic stellate cells and hepatic fibrosis. J. Cell. Biochem. 2022, 123, 1544–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordukalo-Nikšić, T.; Kufner, V.; Vukičević, S. The Role Of BMPs in the Regulation of Osteoclasts Resorption and Bone Remodeling: From Experimental Models to Clinical Applications. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 869422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Mackenzie, N.C.; Shanahan, C.M.; Shroff, R.C.; Farquharson, C.; MacRae, V.E. BMP-9 regulates the osteoblastic differentiation and calcification of vascular smooth muscle cells through an ALK1 mediated pathway. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2015, 19, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Bhargav, D.; Wei, A.; Williams, L.A.; Tao, H.; Ma, D.D.; Diwan, A.D. BMP-13 emerges as a potential inhibitor of bone formation. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2009, 5, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnappa, B.C.; Rubin, E. Modeling alcohol’s effects on organs in animal models. Alcohol Res. Health 2000, 24, 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Osyczka, A.M.; Diefenderfer, D.L.; Bhargave, G.; Leboy, P.S. Different effects of BMP-2 on marrow stromal cells from human and rat bone. Cells Tissues Organs 2004, 176, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Xin, Y.; Hammour, M.M.; Braun, B.; Ehnert, S.; Springer, F.; Vosough, M.; Menger, M.M.; Kumar, A.; Nüssler, A.K.; et al. Establishment of a human 3D in vitro liver-bone model as a potential system for drug toxicity screening. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 333–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, A.M.; Singal, A.G.; Tapper, E.B. Contemporary Epidemiology of Chronic Liver Disease and Cirrhosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 2650–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsen, T.H.; Sheron, N.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Carrieri, P.; Dusheiko, G.; Bugianesi, E.; Pryke, R.; Hutchinson, S.J.; Sangro, B.; Martin, N.K.; et al. The EASL–Lancet Liver Commission: Protecting the next generation of Europeans against liver disease complications and premature mortality. Lancet 2022, 399, 61–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prince, D.S.; Nash, E.; Liu, K. Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease: Evolving Concepts and Treatments. Drugs 2023, 83, 1459–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, M.; Kleber, A.; Ruckelshausen, T.; Betzholz, R.; Manz, A. Differentiation of the human liver progenitor cell line (HepaRG) on a microfluidic-based biochip. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2019, 13, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, J.; Li, Y. In vitro inhibition of hepatic stellate cell activation by the autophagy-related lipid droplet protein ATG2A. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Kim, S.; Heo, J.; Shum, D.; Lee, S.-Y.; Lee, M.; Kim, A.R.; Seo, H.R. Identification of hepatic fibrosis inhibitors through morphometry analysis of a hepatic multicellular spheroids model. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böcker, W.; Yin, Z.; Drosse, I.; Haasters, F.; Rossmann, O.; Wierer, M.; Popov, C.; Locher, M.; Mutschler, W.; Docheva, D.; et al. Introducing a single-cell-derived human mesenchymal stem cell line expressing hTERT after lentiviral gene transfer. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2008, 12, 1347–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghezelayagh, Z.; Zabihi, M.; Zarkesh, I.; Gonçalves, C.A.C.; Larsen, M.; Hagh-parast, N.; Pakzad, M.; Vosough, M.; Arjmand, B.; Baharvand, H.; et al. Improved Differentiation of hESC-Derived Pancreatic Progenitors by Using Human Fetal Pancreatic Mesenchymal Cells in a Micro-scalable Three-Dimensional Co-culture System. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2022, 18, 360–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahmatkesh, E.; Othman, A.; Braun, B.; Aspera, R.; Ruoß, M.; Piryaei, A.; Vosough, M.; Nüssler, A. In vitro modeling of liver fibrosis in 3D microtissues using scalable micropatterning system. Arch. Toxicol. 2022, 96, 1799–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häussling, V.; Deninger, S.; Vidoni, L.; Rinderknecht, H.; Ruoß, M.; Arnscheidt, C.; Athanasopulu, K.; Kemkemer, R.; Nussler, A.K.; Ehnert, S. Impact of Four Protein Additives in Cryogels on Osteogenic Differentiation of Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Bioengineering 2019, 6, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, W.; Häussling, V.; Aspera-Werz, R.H.; Springer, F.; Rinderknecht, H.; Braun, B.; Küper, M.A.; Nussler, A.K.; Ehnert, S. Material-Dependent Formation and Degradation of Bone Matrix-Comparison of Two Cryogels. Bioengineering 2020, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häussling, V.; Aspera-Werz, R.H.; Rinderknecht, H.; Springer, F.; Arnscheidt, C.; Menger, M.M.; Histing, T.; Nussler, A.K.; Ehnert, S. 3D Environment Is Required In Vitro to Demonstrate Altered Bone Metabolism Characteristic for Type 2 Diabetics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammour, M.M.; Othman, A.; Aspera-Werz, R.; Braun, B.; Weis-Klemm, M.; Wagner, S.; Nadalin, S.; Histing, T.; Ruoß, M.; Nüssler, A.K. Optimisation of the HepaRG cell line model for drug toxicity studies using two different cultivation conditions: Advantages and limitations. Arch. Toxicol. 2022, 96, 2511–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspera-Werz, R.H.; Ehnert, S.; Heid, D.; Zhu, S.; Chen, T.; Braun, B.; Sreekumar, V.; Arnscheidt, C.; Nussler, A.K. Nicotine and Cotinine Inhibit Catalase and Glutathione Reductase Activity Contributing to the Impaired Osteogenesis of SCP-1 Cells Exposed to Cigarette Smoke. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 3172480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Weng, W.; Zhang, S.; Rinderknecht, H.; Braun, B.; Breinbauer, R.; Gupta, P.; Kumar, A.; Ehnert, S.; Histing, T.; et al. Maqui Berry and Ginseng Extracts Reduce Cigarette Smoke-Induced Cell Injury in a 3D Bone Co-Culture Model. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Häussling, V.; Aspera-Werz, R.H.; Chen, T.; Braun, B.; Weng, W.; Histing, T.; Nussler, A.K. Bisphosphonates Reduce Smoking-Induced Osteoporotic-Like Alterations by Regulating RANKL/OPG in an Osteoblast and Osteoclast Co-Culture Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godel, M.; Morena, D.; Ananthanarayanan, P.; Buondonno, I.; Ferrero, G.; Hattinger, C.M.; Di Nicolantonio, F.; Serra, M.; Taulli, R.; Cordero, F.; et al. Small Nucleolar RNAs Determine Resistance to Doxorubicin in Human Osteosarcoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspera-Werz, R.H.; Chen, T.; Ehnert, S.; Zhu, S.; Fröhlich, T.; Nussler, A.K. Cigarette Smoke Induces the Risk of Metabolic Bone Diseases: Transforming Growth Factor Beta Signaling Impairment via Dysfunctional Primary Cilia Affects Migration, Proliferation, and Differentiation of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Huo, R.; Yan, Z.; Xu, H.; Li, H.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, L.; Weng, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; et al. Mesenchymal Behavior of the Endothelium Promoted by SMAD6 Downregulation Is Associated with Brain Arteriovenous Malformation Microhemorrhage. Stroke 2020, 51, 2197–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.W.; Holmgren, P. Comparison of blood-ethanol concentration in deaths attributed to acute alcohol poisoning and chronic alcoholism. J. Forensic Sci. 2003, 48, 874–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, B.; Addante, A.; Sánchez, A. BMP Signalling at the Crossroad of Liver Fibrosis and Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Li, Y.Y.; Nio, K.; Tang, H. Unveiling the Impact of BMP9 in Liver Diseases: Insights into Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Potential. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Zou, J.; Wang, W.; Yang, A. BMP2 induces hMSC osteogenesis and matrix remodeling. Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 23, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Mao, K.; Li, J.; Cui, Q.; Wang, G.-J. Alcohol-Induced Adipogenesis in Bone and Marrow: A Possible Mechanism for Osteonecrosis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res.® 2003, 410, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.A.; Doratt, B.M.; Qiao, Q.; Blanton, M.; Grant, K.A.; Messaoudi, I. Integrated single cell analysis shows chronic alcohol drinking disrupts monocyte differentiation in the bone marrow. Stem Cell Rep. 2023, 18, 1884–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Q.; Wang, Y.; Saleh, K.J.; Wang, G.J.; Balian, G. Alcohol-induced adipogenesis in a cloned bone-marrow stem cell. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2006, 88, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wei, W.; Krzeszinski, J.Y.; Wang, Y.; Wan, Y. A Liver-Bone Endocrine Relay by IGFBP1 Promotes Osteoclastogenesis and Mediates FGF21-Induced Bone Resorption. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 811–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Qin, L.; Chen, S.; Huo, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, F.; Yi, W.; Mei, Y.; Xiao, G. Bone-derived factors mediate crosstalk between skeletal and extra-skeletal organs. Bone Res. 2025, 13, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiProspero, T.J.; Brown, L.G.; Fachko, T.D.; Lockett, M.R. HepaRG cells adopt zonal-like drug-metabolizing phenotypes under physiologically relevant oxygen tensions and Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2022, 50, 1098–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Yuan, W.G.; He, P.; Lei, J.H.; Wang, C.X. Liver fibrosis and hepatic stellate cells: Etiology, pathological hallmarks and therapeutic targets. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 10512–10522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocherova, I.; Bryja, A.; Mozdziak, P.; Angelova Volponi, A.; Dyszkiewicz-Konwińska, M.; Piotrowska-Kempisty, H.; Antosik, P.; Bukowska, D.; Bruska, M.; Iżycki, D.; et al. Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs) Co-Culture with Osteogenic Cells: From Molecular Communication to Engineering Prevascularised Bone Grafts. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, M.; Tam, H.; Zheng, H.; Tracy, T.S. CYP2C9-CYP3A4 protein-protein interactions: Role of the hydrophobic N terminus. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2010, 38, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsden, D.; Tweedie, D.J.; Chan, T.S.; Tracy, T.S. Altered CYP2C9 activity following modulation of CYP3A4 levels in human hepatocytes: An example of protein-protein interactions. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2014, 42, 1940–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Huang, S.; Jiang, H.; Ma, Q.; Qiu, J.; Luo, Q.; Cao, C.; Xu, Y.; Chen, F.; Chen, Y.; et al. Alcohol-related liver disease (ALD): Current perspectives on pathogenesis, therapeutic strategies, and animal models. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1432480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussler, A.K.; Wildemann, B.; Freude, T.; Litzka, C.; Soldo, P.; Friess, H.; Hammad, S.; Hengstler, J.G.; Braun, K.F.; Trak-Smayra, V.; et al. Chronic CCl4 intoxication causes liver and bone damage similar to the human pathology of hepatic osteodystrophy: A mouse model to analyse the liver-bone axis. Arch. Toxicol. 2014, 88, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Latchoumycandane, C.; McMullen, M.R.; Pratt, B.T.; Zhang, R.; Papouchado, B.G.; Nagy, L.E.; Feldstein, A.E.; McIntyre, T.M. Chronic alcohol exposure increases circulating bioactive oxidized phospholipids. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 22211–22220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åberg, F.; Byrne, C.D.; Pirola, C.J.; Männistö, V.; Sookoian, S. Alcohol consumption and metabolic syndrome: Clinical and epidemiological impact on liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2023, 78, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, T.; Fuchs, B.C.; Yamada, S.; Lauwers, G.Y.; Kulu, Y.; Goodwin, J.M.; Lanuti, M.; Tanabe, K.K. Mouse model of carbon tetrachloride induced liver fibrosis: Histopathological changes and expression of CD133 and epidermal growth factor. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, J.; Lin, D.; Zhang, J.; Habib, P.; Smith, P.; Murtha, J.; Fu, Z.; Yao, Z.; Qi, Y.; Keller, E.T. Chronic alcohol ingestion induces osteoclastogenesis and bone loss through IL-6 in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2000, 106, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Almeida, J.M.; Pazmino, V.F.C.; Novaes, V.C.N.; Bomfim, S.R.M.; Nagata, M.J.H.; Oliveira, F.L.P.; Matheus, H.R.; Ervolino, E. Chronic consumption of alcohol increases alveolar bone loss. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, S.A.; Buckendahl, P.; Sampson, H.W. Alcohol consumption inhibits osteoblastic cell proliferation and activity in vivo. Alcohol 1998, 16, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Huang, Y.L.; Wu, Q.; Chai, L.; Jiang, Z.Z.; Zeng, Y.; Wan, S.R.; Tan, X.Z.; Long, Y.; Gu, J.L.; et al. Chronic Ethanol Consumption Induces Osteopenia via Activation of Osteoblast Necroptosis. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 3027954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamiya, N.; Kobayashi, T.; Mochida, Y.; Yu, P.B.; Yamauchi, M.; Kronenberg, H.M.; Mishina, Y. Wnt inhibitors Dkk1 and Sost are downstream targets of BMP signaling through the type IA receptor (BMPRIA) in osteoblasts. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010, 25, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Li, W.; Jiang, K.; Lin, Z.; Qian, C.; Wu, M.; Xia, Y.; Li, N.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, H.; et al. Regulation of bone homeostasis: Signaling pathways and therapeutic targets. MedComm 2024, 5, e657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beederman, M.; Lamplot, J.D.; Nan, G.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Yin, L.; Li, R.; Shui, W.; Zhang, H.; Kim, S.H.; et al. BMP signaling in mesenchymal stem cell differentiation and bone formation. J. Biomed. Sci. Eng. 2013, 6, 32–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Q.; Song, W.X.; Luo, Q.; Tang, N.; Luo, J.; Luo, X.; Chen, J.; Bi, Y.; He, B.C.; Park, J.K.; et al. A comprehensive analysis of the dual roles of BMPs in regulating adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal progenitor cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2009, 18, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, L. BMP signaling and stem cell regulation. Dev. Biol. 2005, 284, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerjevic, L.N.; Liu, N.; Lu, S.; Harrison-Findik, D.D. Alcohol Activates TGF-Beta but Inhibits BMP Receptor-Mediated Smad Signaling and Smad4 Binding to Hepcidin Promoter in the Liver. Int. J. Hepatol. 2012, 2012, 459278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, W.G.; Kim, E.J.; Kim, D.K.; Ryoo, H.M.; Lee, K.B.; Kim, S.H.; Choi, H.S.; Koh, J.T. BMP2 protein regulates osteocalcin expression via Runx2-mediated Atf6 gene transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berasi, S.P.; Varadarajan, U.; Archambault, J.; Cain, M.; Souza, T.A.; Abouzeid, A.; Li, J.; Brown, C.T.; Dorner, A.J.; Seeherman, H.J.; et al. Divergent activities of osteogenic BMP2, and tenogenic BMP12 and BMP13 independent of receptor binding affinities. Growth Factors 2011, 29, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Svoboda, K.K.H.; Feng, J.Q.; Jiang, X. The biological function of type I receptors of bone morphogenetic protein in bone. Bone Res. 2016, 4, 16005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, C. The role of bone morphogenetic proteins in liver fibrosis. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 12, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersten, V.; Seitz, T.; Sommer, J.; Thasler, W.E.; Bosserhoff, A.; Hellerbrand, C. Bone Morphogenetic Protein 13 Has Protumorigenic Effects on Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells In Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaither, K.A.; Yue, G.; Singh, D.K.; Trudeau, J.; Ponraj, K.; Davydova, N.Y.; Lazarus, P.; Davydov, D.R.; Prasad, B. Effects of Chronic Alcohol Intake on the Composition of the Ensemble of Drug-Metabolizing Enzymes and Transporters in the Human Liver. J. Xenobiotics 2025, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Chen, W.; Masson, A.; Li, Y.-P. Cell signaling and transcriptional regulation of osteoblast lineage commitment, differentiation, bone formation, and homeostasis. Cell Discov. 2024, 10, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.H.; Hatzopoulos, A.K. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling in inflammation. Exp. Biol. Med. 2019, 244, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Teng, X.; Zheng, Q.; Chen, P. The regulatory mechanism of p38/MAPK in the chondrogenic differentiation from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2019, 14, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Gao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Guan, M.X. The role of mitochondria in osteogenic, adipogenic and chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Protein Cell 2017, 8, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoudam, T.; Gao, H.; Jiang, Y.; Huda, N.; Yang, Z.; Ma, J.; Liangpunsakul, S. Mitochondrial quality control in alcohol-associated liver disease. Hepatol. Commun. 2024, 8, e0534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmegeed, M.A.; Ha, S.K.; Choi, Y.; Akbar, M.; Song, B.J. Role of CYP2E1 in Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Hepatic Injury by Alcohol and Non-Alcoholic Substances. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 2017, 10, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, L.; He, X.; Farmer, P.; Boden, S.; Kozlowski, M.; Rubin, J.; Nanes, M.S. Inhibition of osteoblast differentiation by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Endocrinology 2000, 141, 3956–3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Li, Y.; Shu, T.; Wang, J. Cytokines and inflammation in adipogenesis: An updated review. Front. Med. 2019, 13, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yin, H.; Yan, Z.; Li, H.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Wei, F.; Tian, G.; Ning, C.; Li, H.; et al. The immune microenvironment in cartilage injury and repair. Acta Biomater. 2022, 140, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.; Zheng, Q.; Engin, F.; Munivez, E.; Chen, Y.; Sebald, E.; Krakow, D.; Lee, B. Dominance of SOX9 function over RUNX2 during skeletogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 19004–19009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, K.N.; Lie, J.D.; Wan, C.K.V.; Cameron, M.; Austel, A.G.; Nguyen, J.K.; Van, K.; Hyun, D. Osteoporosis: A Review of Treatment Options. Pharm. Ther. 2018, 43, 92–104. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Hong, M.; Tan, H.Y.; Wang, N.; Feng, Y. Insights into the Role and Interdependence of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Liver Diseases. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 4234061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xin, Y.; Chen, G.; Hammour, M.M.; Gao, X.; Springer, F.; Maurer, E.; Nüssler, A.K.; Aspera-Werz, R.H. Three-Dimensional Human Liver Micro Organoids and Bone Co-Culture Mimics Alcohol-Induced BMP Dysregulation and Bone Remodeling Defects. Cells 2026, 15, 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030274

Xin Y, Chen G, Hammour MM, Gao X, Springer F, Maurer E, Nüssler AK, Aspera-Werz RH. Three-Dimensional Human Liver Micro Organoids and Bone Co-Culture Mimics Alcohol-Induced BMP Dysregulation and Bone Remodeling Defects. Cells. 2026; 15(3):274. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030274

Chicago/Turabian StyleXin, Yuxuan, Guanqiao Chen, Mohammad Majd Hammour, Xiang Gao, Fabian Springer, Elke Maurer, Andreas K. Nüssler, and Romina H. Aspera-Werz. 2026. "Three-Dimensional Human Liver Micro Organoids and Bone Co-Culture Mimics Alcohol-Induced BMP Dysregulation and Bone Remodeling Defects" Cells 15, no. 3: 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030274

APA StyleXin, Y., Chen, G., Hammour, M. M., Gao, X., Springer, F., Maurer, E., Nüssler, A. K., & Aspera-Werz, R. H. (2026). Three-Dimensional Human Liver Micro Organoids and Bone Co-Culture Mimics Alcohol-Induced BMP Dysregulation and Bone Remodeling Defects. Cells, 15(3), 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030274