Extracellular Vesicle Associated Proteomic Biomarkers in Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

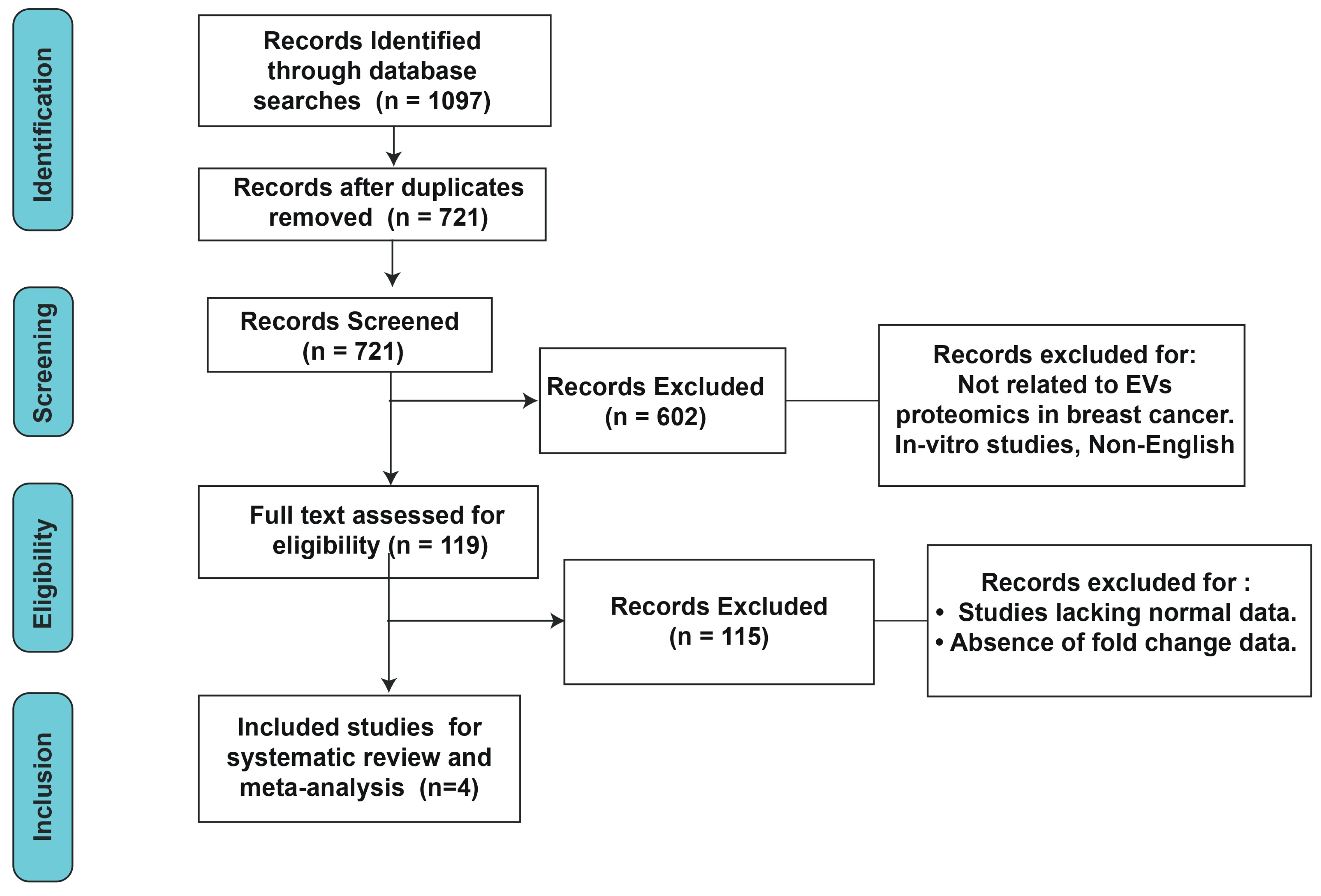

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Meta-Analysis

2.5. Functional Enrichment and Pathway Analysis

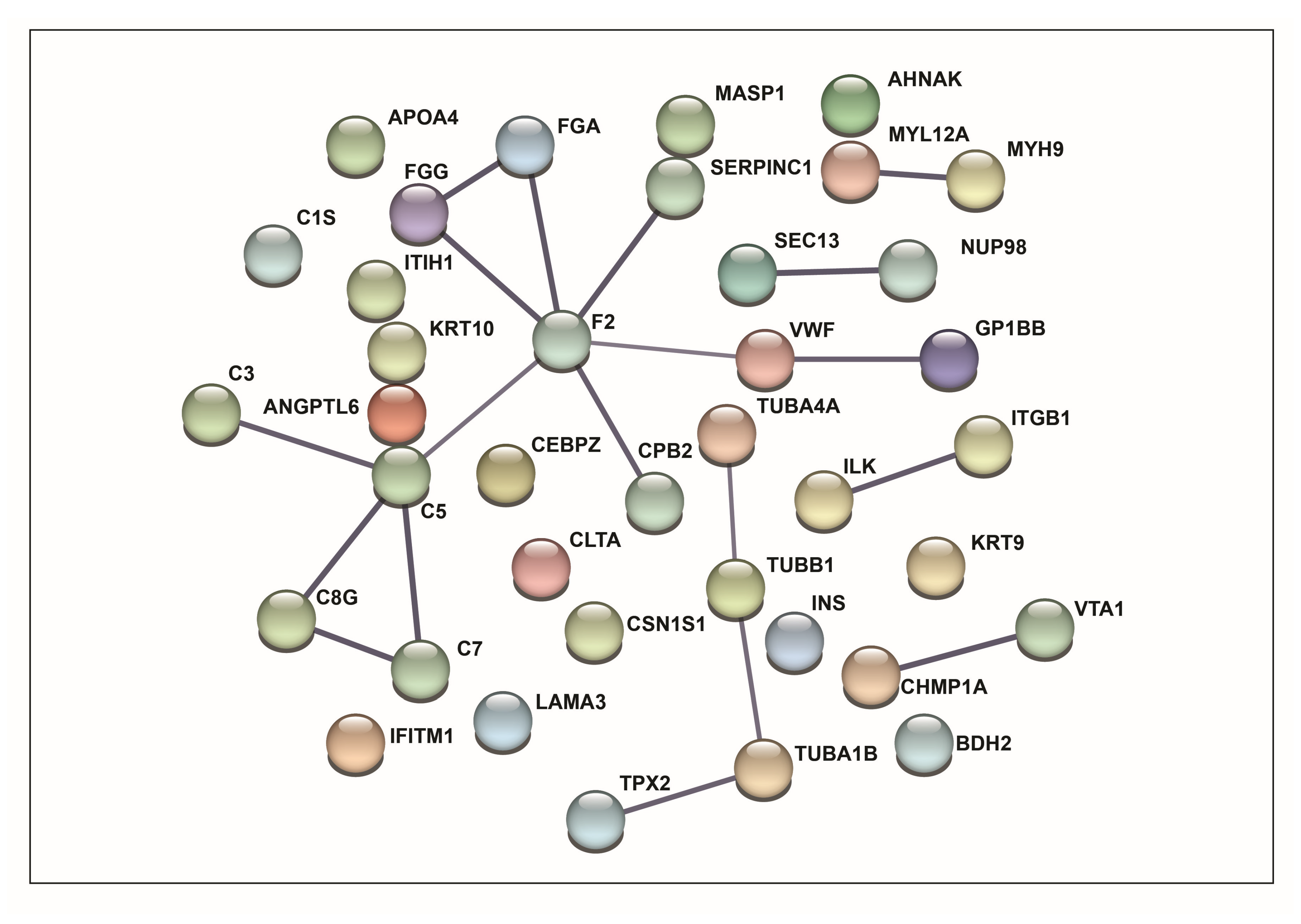

3. Results

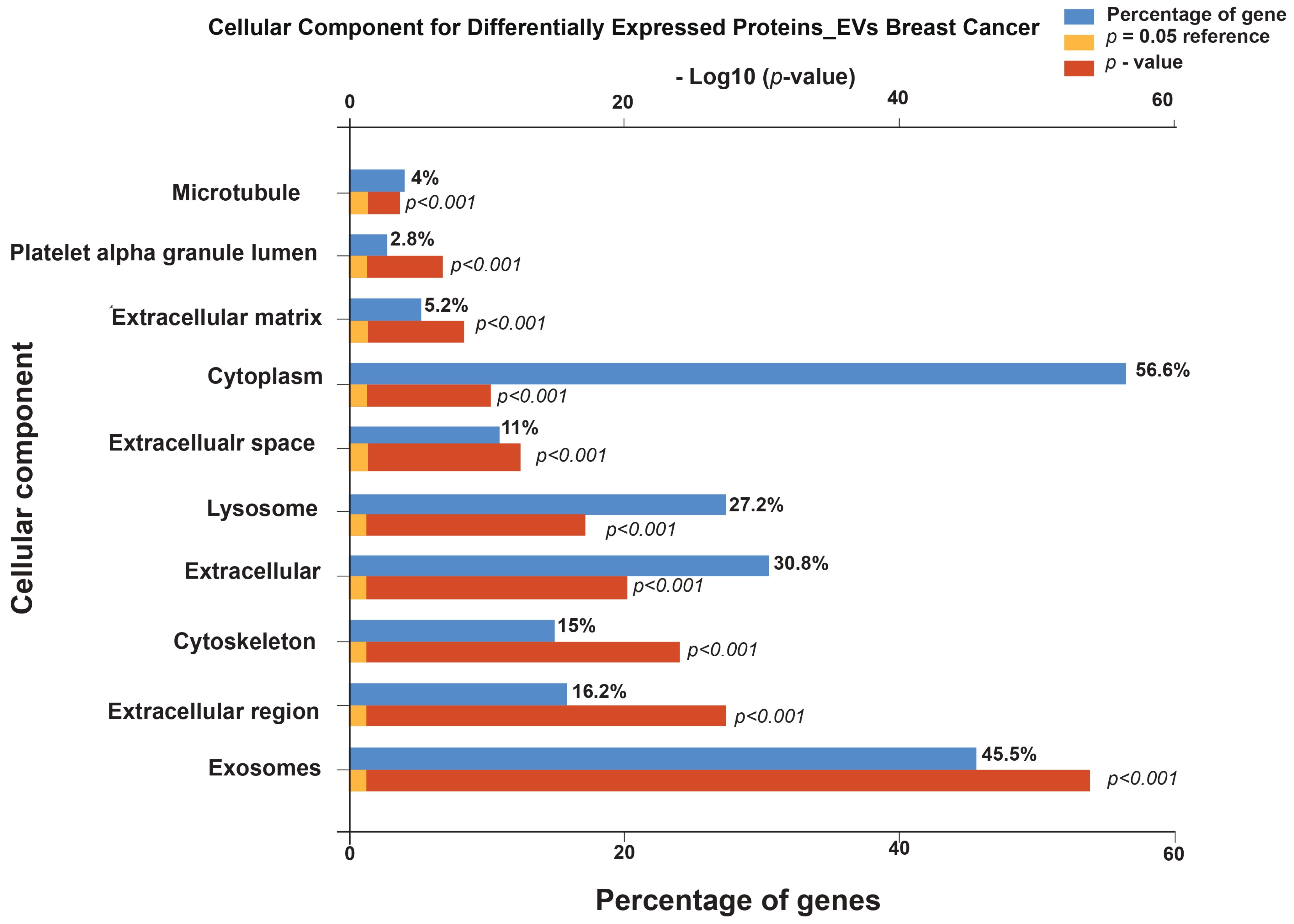

3.1. Functional Enrichment Analysis

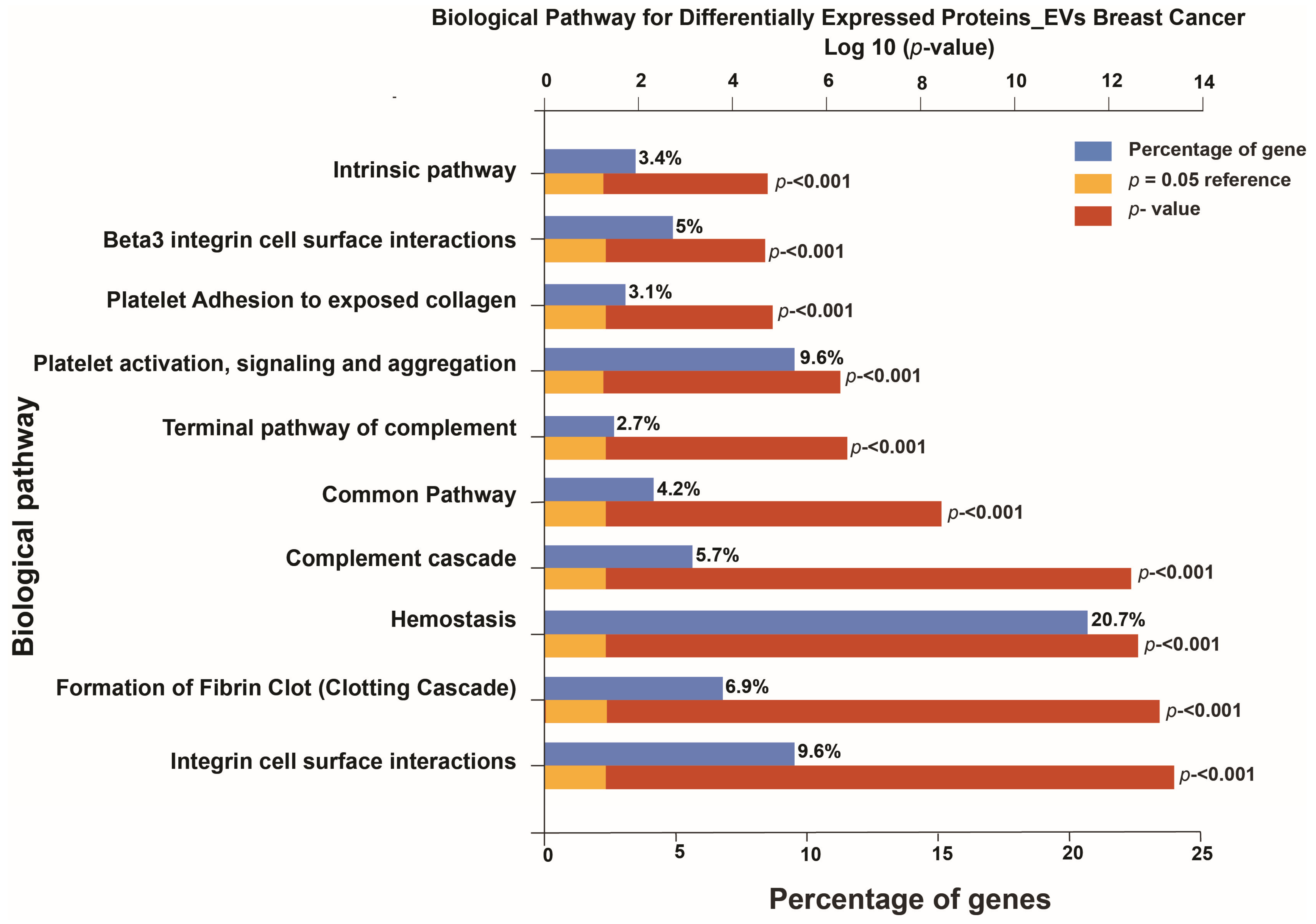

3.2. Pathway Analysis

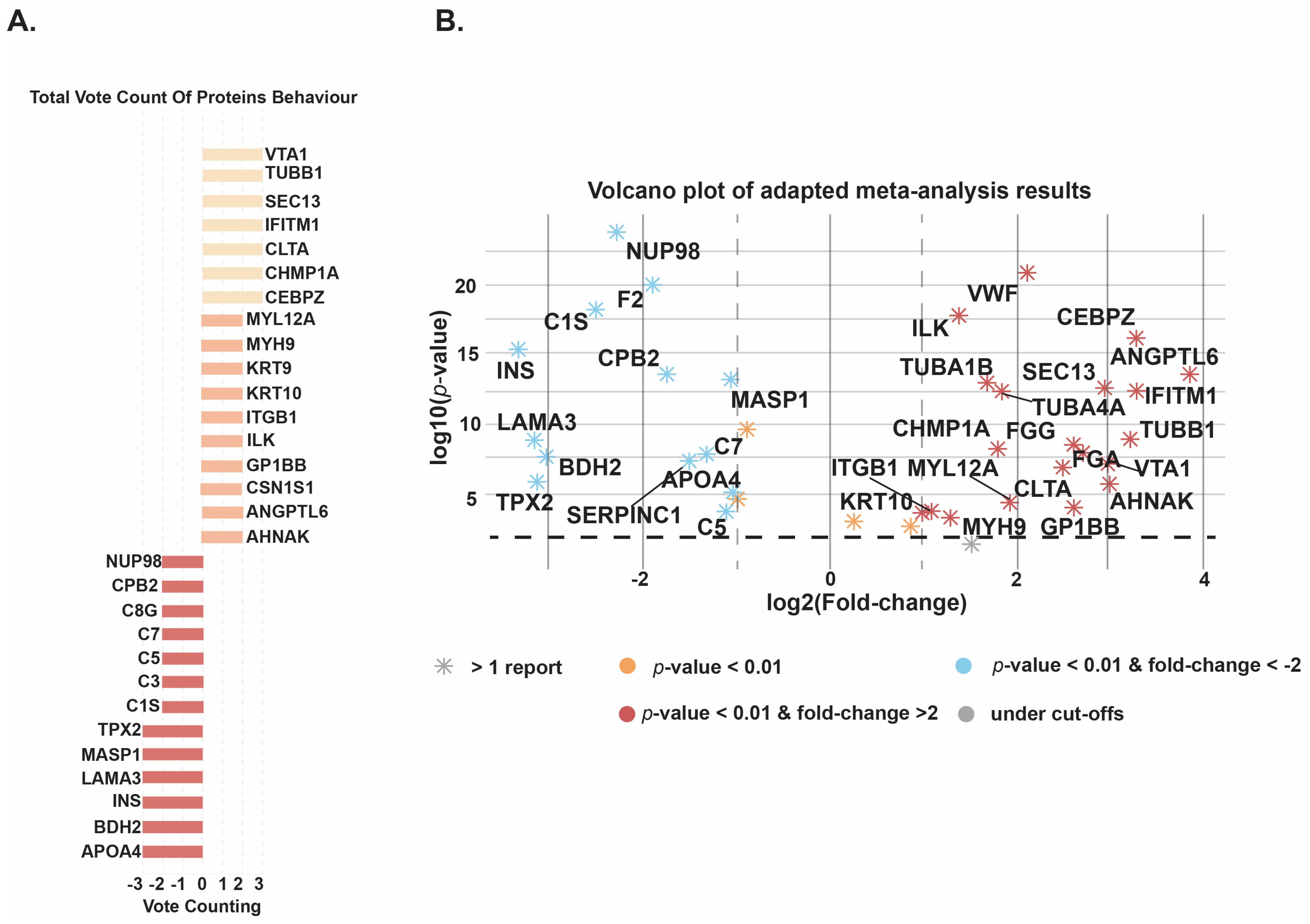

3.3. Meta-Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. Early Diagnosis of Breast Cancer. Sensors 2017, 17, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, F.J.; Pinker-Domenig, K. Diagnosis and Staging of Breast Cancer: When and How to Use Mammography, Tomosynthesis, Ultrasound, Contrast-Enhanced Mammography, and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. In Diseases of the Chest, Breast, Heart and Vessels 2019–2022: Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging; Hodler, J., Kubik-Huch, R.A., von Schulthess, G.K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 155–166. [Google Scholar]

- Tsarouchi, M.; Hoxhaj, A.; Portaluri, A.; Sung, J.; Sechopoulos, I.; Pinker-Domenig, K.; Mann, R.M. Breast cancer staging with contrast-enhanced imaging. The benefits and drawbacks of MRI, CEM, and dedicated breast CT. Eur. J. Radiol. 2025, 185, 112013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagopoulou, M.; Esteller, M.; Chatzaki, E. Circulating Cell-Free DNA in Breast Cancer: Searching for Hidden Information towards Precision Medicine. Cancers 2021, 13, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beca, F.; Polyak, K. Intratumor Heterogeneity in Breast Cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016, 882, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alimirzaie, S.; Bagherzadeh, M.; Akbari, M.R. Liquid Biopsy in Breast Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Clin. Genet. 2019, 95, 643–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Cao, H.; Mao, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, N.; Luo, P.; Xue, J.; et al. Liquid biopsy for human cancer: Cancer screening, monitoring, and treatment. Medcomm 2024, 5, e564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xue, F.; Russo, A.; Wan, Y. Proteomic Analysis of Extracellular Vesicles Derived from MDA-MB-231 Cells in Microgravity. Protein J. 2021, 40, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rontogianni, S.; Synadaki, E.; Li, B.; Liefaard, M.C.; Lips, E.H.; Wesseling, J.; Wu, W.; Altelaar, M. Proteomic profiling of extracellular vesicles allows for human breast cancer subtyping. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Feng, J.; Luo, T.; Tan, Y.; Situ, B.; Nieuwland, R.; Guo, J.; Liu, C.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; et al. Rapid and efficient isolation platform for plasma extracellular vesicles: EV-FISHER. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2022, 11, e12281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Niel, G.; D’Angelo, G.; Raposo, G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sódar, B.W.; Kittel, Á.; Pálóczi, K.; Vukman, K.V.; Osteikoetxea, X.; Szabó-Taylor, K.; Németh, A.; Sperlágh, B.; Baranyai, T.; Giricz, Z.; et al. Low-density lipoprotein mimics blood plasma-derived exosomes and microvesicles during isolation and detection. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willms, E.; Johansson, H.J.; Mäger, I.; Lee, Y.; Blomberg, K.E.M.; Sadik, M.; Alaarg, A.; Smith, C.E.; Lehtiö, J.; EL Andaloussi, S.; et al. Cells release subpopulations of exosomes with distinct molecular and biological properties. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linares, R.; Tan, S.; Gounou, C.; Arraud, N.; Brisson, A.R. High-speed centrifugation induces aggregation of extracellular vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 29509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, E.Á.; Turiák, L.; Visnovitz, T.; Cserép, C.; Mázló, A.; Sódar, B.W.; Försönits, A.I.; Petővári, G.; Sebestyén, A.; Komlósi, Z.; et al. Formation of a protein corona on the surface of extracellular vesicles in blood plasma. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10, e12140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, K.K.M.; Al Dhubaib, B.E. Zotero: A bibliographic assistant to researcher. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2011, 2, 304–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llambrich, M.; Correig, E.; Gumà, J.; Brezmes, J.; Cumeras, R. Amanida: An R package for meta-analysis of metabolomics non-integral data. Bioinformatics 2021, 38, 583–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathan, M.; Keerthikumar, S.; Ang, C.-S.; Gangoda, L.; Quek, C.Y.; Williamson, N.A.; Mouradov, D.; Sieber, O.M.; Simpson, R.J.; Salim, A.; et al. FunRich: An open access standalone functional enrichment and interaction network analysis tool. Proteomics 2015, 15, 2597–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING database in 2023: Protein–protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.I.; Park, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, X.; Han, Y.; Zhang, D. Recent advances in extracellular vesicles for therapeutic cargo delivery. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 836–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, S.L.N.; Breakefield, X.O.; Weaver, A.M. Extracellular Vesicles: Unique Intercellular Delivery Vehicles. Trends Cell Biol. 2017, 27, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hessvik, N.P.; Llorente, A. Current knowledge on exosome biogenesis and release. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajimoto, T.; Okada, T.; Miya, S.; Zhang, L.; Nakamura, S.-I. Ongoing activation of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors mediates maturation of exosomal multivesicular endosomes. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trajkovic, K.; Hsu, C.; Chiantia, S.; Rajendran, L.; Wenzel, D.; Wieland, F.; Schwille, P.; Brügger, B.; Simons, M. Ceramide Triggers Budding of Exosome Vesicles into Multivesicular Endosomes. Science 2008, 319, 1244–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvjetkovic, A.; Jang, S.C.; Konečná, B.; Höög, J.L.; Sihlbom, C.; Lässer, C.; Lötvall, J. Detailed Analysis of Protein Topology of Extracellular Vesicles–Evidence of Unconventional Membrane Protein Orientation. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhang, W.; Yang, W.; Feng, Q.; Wang, H. Extracellular signals regulate the biogenesis of extracellular vesicles. Biol. Res. 2022, 55, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, F.; Vayalil, J.; Lee, G.; Wang, Y.; Peng, G. Emerging role of tumor-derived extracellular vesicles in T cell suppression and dysfunction in the tumor microenvironment. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e003217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, J.; Carrese, B.; Peluso, M.S.; Coppola, L.; D’aiuto, M.; Mossetti, G.; Salvatore, M.; Smaldone, G. Influence of Breast Cancer Extracellular Vesicles on Immune Cell Activation: A Pilot Study. Biology 2023, 12, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, P.M.M.; Alkhilaiwi, F.; Cavalli, I.J.; Malheiros, D.; de Souza Fonseca Ribeiro, E.M.; Cavalli, L.R. Extracellular vesicles from triple-negative breast cancer cells promote proliferation and drug resistance in non-tumorigenic breast cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 172, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leone, I.; Santoro, J.; Soricelli, A.; Febbraro, A.; Santoriello, A.; Carrese, B. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer EVs Modulate Growth and Migration of Normal Epithelial Lung Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, P.; Sesé, M.; Guijarro, P.J.; Emperador, M.; Sánchez-Redondo, S.; Peinado, H.; Hümmer, S.; Cajal, S.R.Y. ITGB3-mediated uptake of small extracellular vesicles facilitates intercellular communication in breast cancer cells. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lai, S.; Qu, F.; Li, Z.; Fu, X.; Li, Q.; Zhong, X.; Wang, C.; Li, H. CCL18 promotes breast cancer progression by exosomal miR-760 activation of ARF6/Src/PI3K/Akt pathway. Mol. Ther.—Oncol. 2022, 25, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Lu, Y.; Yu, L.; Han, X.; Wang, H.; Mao, J.; Shen, J.; Wang, B.; Tang, J.; Li, C.; et al. miR-221/222 promote cancer stem-like cell properties and tumor growth of breast cancer via targeting PTEN and sustained Akt/NF-κB/COX-2 activation. Chem. Interact. 2017, 277, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurwitz, S.N.; Meckes, D.G., Jr. Extracellular Vesicle Integrins Distinguish Unique Cancers. Proteomes 2019, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, R.O. Integrins: Versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell 1992, 69, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, G.; Yang, X.; Hu, J.; Zhang, X.; Feng, G.; Wang, H. Integrin α6-Targeted Molecular Imaging of Central Nervous System Leukemia in Mice. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 812277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Qu, J.; He, L.; Peng, H.; Chen, P.; Zhou, Y. α6-Integrin alternative splicing: Distinct cytoplasmic variants in stem cell fate specification and niche interaction. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, E.J.; Na Kim, H.; Hsieh, Y.-T.; Ruan, Y.; Ogana, H.A.; Lee, S.; Pham, J.; Geng, H.; Park, E.; Klemm, L.; et al. Integrin α6 mediates the drug resistance of acute lymphoblastic B-cell leukemia. Blood 2020, 136, 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, P.C.; Dedhar, S. New Perspectives on the Role of Integrin-Linked Kinase (ILK) Signaling in Cancer Metastasis. Cancers 2022, 14, 3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asada, T.; Nakahata, S.; Fauzi, Y.R.; Ichikawa, T.; Inoue, K.; Shibata, N.; Fujii, Y.; Imamura, N.; Hiyoshi, M.; Nanashima, A.; et al. Integrin α6A (ITGA6A)-type Splice Variant in Extracellular Vesicles Has a Potential as a Novel Marker of the Early Recurrence of Pancreatic Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2022, 42, 1763–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arraud, N.; Linares, R.; Tan, S.; Gounou, C.; Pasquet, J.; Mornet, S.; Brisson, A.R. Extracellular vesicles from blood plasma: Determination of their morphology, size, phenotype and concentration. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2014, 12, 614–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyorgy, B.; Modos, K.; Pallinger, E.; Paloczi, K.; Pasztoi, M.; Misjak, P.; Deli, M.A.; Sipos, A.; Szalai, A.; Voszka, I.; et al. Detection and Isolation of Cell-Derived Microparticles Are Compromised by Protein Complexes Resulting from Shared Biophysical Parameters. Blood 2011, 117, e39–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, J.B. What Are We Looking At? Extracellular Vesicles, Lipoproteins, or Both? Circ. Res. 2017, 121, 920–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- héry, C.; Witwer, K.W.; Aikawa, E.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Anderson, J.D.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Antoniou, A.; Arab, T.; Archer, F.; Atkin-Smith, G.K.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1535750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böing, A.N.; van der Pol, E.; Grootemaat, A.E.; Coumans, F.A.W.; Sturk, A.; Nieuwland, R. Single-step isolation of extracellular vesicles by size-exclusion chromatography. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2014, 3, 23430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreu, Z.; Hidalgo, M.R.; Masiá, E.; Romera-Giner, S.; Malmierca-Merlo, P.; López-Guerrero, J.A.; García-García, F.; Vicent, M.J. Comparative profiling of whole-cell and exosome samples reveals protein signatures that stratify breast cancer subtypes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Huang, R.; Wumaier, R.; Lyu, J.; Huang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Liu, W.; Tao, M.; Li, J.; et al. Proteomic Profiling of Serum Extracellular Vesicles Identifies Diagnostic Signatures and Therapeutic Targets in Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 3267–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, M.; Mao, X.-Y.; Chang, H.; Perez-Losada, J.; Mao, J.-H. Distinct Clinical Impact and Biological Function of Angiopoietin and Angiopoietin-like Proteins in Human Breast Cancer. Cells 2021, 10, 2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.; Raposo, G.; Théry, C. Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014, 30, 255–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Zhou, C.; Ma, R.; Guo, Q.; Huang, H.; Hao, J.; Liu, H.; Shi, R.; Liu, B. Prognostic value of increased integrin-beta 1 expression in solid cancers: A meta-analysis. OncoTargets Ther. 2018, 11, 1787–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, C.Y.; Patmore, S.; Smolenski, A.; Howard, J.; Evans, S.; O’SUllivan, J.; McCann, A. The role of von Willebrand factor in breast cancer metastasis. Transl. Oncol. 2021, 14, 101033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Altered Pathway | Number of Proteins from Dataset | Proteins from Background Dataset | p-Value | Bonferroni Method | BH Method | Q-Value (Storey–Tibshirani Method) | Altered Proteins from the Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrin family cell surface interactions | 96 | 1375 | 1.42 × 10−8 | 2.37021 × 10−5 | 2.15474 × 10−8 | 9.5009 × 10−6 | CLTA; CEBPZ; AHSG; COL1A1; FGG; FGA; FGB; ITGA6; FBN1; TLN1; TYK2; GSK3B; MDM4; GAB1; DMP1; TIAM1; ITGAE; ACTN1; MED1; ALDH9A1; ARPC1B; ARPC2; ARPC3; BAIAP2; CALM1; CALM2; CALM3; CDC42; CDH1; CLIP1; COL1A2; COL3A1; COL5A1; COL7A1; CSF1R; CSK; CTNNB1; F11R; FN1; FYN; GNA13; GNAI1; GNAO1; HSPA1A; HSPA1B; ICAM1; ICAM2; ITGA2B; ITGB1; ITGB3; LAMA2; LIMA1; MMP2; NCKAP1; NDRG1; NFKB2; PECAM1; PGK1; PPP2R1A; PPP5C; PRKCD; PTK2; PTPRC; PTPRJ; PXN; RAP1A; RAP1B; RUNX1; STAT5A; STAT5B; TNC; VCAM1; YES1; ZYX; LAMA3; INS; C3; CLU; GSN; FTH1; F10; KNG1; MST1; LRP1; VTN; PGM1; NF1; AP2A1; ARF1; CAPN2; CTTN; DNM1; DNM2; MMP3; RAB11A; SPAG9; |

| Beta1 integrin cell surface interactions | 90 | 1348 | 4.67 × 10−7 | 0.000779588 | 4.1031 × 10−5 | 0.000180918 | CLTA; CEBPZ; AHSG; COL1A1; FGG; FGA; FGB; ITGA6; FBN1; TLN1; TYK2; GSK3B; MDM4; GAB1; DMP1; TIAM1; ITGAE; ACTN1; MED1; ALDH9A1; ARPC1B; ARPC2; ARPC3; BAIAP2; CALM1; CALM2; CALM3; CDC42; CDH1; CLIP1; COL1A2; COL3A1; COL5A1; COL7A1; CSF1R; CSK; CTNNB1; FN1; FYN; GNA13; GNAI1; GNAO1; HSPA1A; HSPA1B; ICAM1; ITGA2B; ITGB1; ITGB3; LAMA2; LIMA1; MMP2; NCKAP1; NDRG1; NFKB2; PGK1; PPP2R1A; PPP5C; PRKCD; PTK2; PTPRC; PTPRJ; PXN; RAP1A; RAP1B; RUNX1; STAT5A; STAT5B; TNC; VCAM1; YES1; ZYX; LAMA3; INS; CLU; GSN; FTH1; MST1; LRP1; VTN; PGM1; NF1; AP2A1; ARF1; CAPN2; CTTN; DNM1; DNM2; MMP3; RAB11A; SPAG9; |

| Proteoglycan syndecan-mediated signaling events | 89 | 1342 | 7.69 × 10−7 | 0.001281882 | 6.40941 × 10−5 | 0.000282611 | CLTA; CEBPZ; F2; AHSG; COL1A1; FGG; FGA; FGB; ITGA6; TLN1; TYK2; GSK3B; MDM4; GAB1; DMP1; TIAM1; ITGAE; ACTN1; MED1; ALDH9A1; ARPC1B; ARPC2; ARPC3; BAIAP2; CALM1; CALM2; CALM3; CDC42; CDH1; CLIP1; COL1A2; CSF1R; CSK; CTNNB1; EZR; FN1; FYN; GNA13; GNAI1; GNAO1; HSPA1A; HSPA1B; ICAM1; ITGA2B; ITGB1; ITGB3; LIMA1; MMP2; NCKAP1; NDRG1; NFKB2; PGK1; PPP2R1A; PPP5C; PRKCD; PTK2; PTPRC; PTPRJ; PXN; RAP1A; RAP1B; RUNX1; STAT5A; STAT5B; TNC; YES1; ZYX; LAMA3; INS; CLU; BSG; GSN; FTH1; KNG1; MST1; LRP1; VTN; PGM1; NF1; AP2A1; ARF1; CAPN2; CTTN; DNM1; DNM2; MMP3; RAB11A; SDCBP; SPAG9; |

| TRAIL signaling pathway | 86 | 1325 | 3.37 × 10−6 | 0.005617398 | 0.000170224 | 0.000750571 | CLTA; CEBPZ; AHSG; COL1A1; FGG; FGA; FGB; ITGA6; TLN1; TYK2; GSK3B; MDM4; NUMA1; GAB1; DMP1; TIAM1; ITGAE; ACTN1; MED1; ALDH9A1; ARPC1B; ARPC2; ARPC3; BAIAP2; CALM1; CALM2; CALM3; CDC42; CDH1; CFL2; CLIP1; COL1A2; CSF1R; CSK; CTNNB1; FN1; FYN; GNA13; GNAI1; GNAO1; HSPA1A; HSPA1B; ICAM1; ITGA2B; ITGB1; ITGB3; LIMA1; MMP2; NCKAP1; NDRG1; NFKB2; PGK1; PPP2R1A; PPP5C; PRKCD; PTK2; PTPRC; PTPRJ; PXN; RAP1A; RAP1B; RUNX1; STAT5A; STAT5B; TFAP2A; YES1; ZYX; LAMA3; INS; CLU; GSN; FTH1; MST1; LRP1; VTN; PGM1; NF1; AP2A1; ARF1; CAPN2; CTTN; DNM1; DNM2; MMP3; RAB11A; SPAG9; |

| Syndecan-1-mediated signaling events | 85 | 1297 | 2.64 × 10−6 | 0.004401549 | 0.000151778 | 0.000669234 | CLTA; CEBPZ; AHSG; COL1A1; FGG; FGA; FGB; ITGA6; TLN1; TYK2; GSK3B; MDM4; GAB1; DMP1; TIAM1; ITGAE; ACTN1; MED1; ALDH9A1; ARPC1B; ARPC2; ARPC3; BAIAP2; CALM1; CALM2; CALM3; CDC42; CDH1; CLIP1; COL1A2; CSF1R; CSK; CTNNB1; FN1; FYN; GNA13; GNAI1; GNAO1; HSPA1A; HSPA1B; ICAM1; ITGA2B; ITGB1; ITGB3; LIMA1; MMP2; NCKAP1; NDRG1; NFKB2; PGK1; PPP2R1A; PPP5C; PRKCD; PTK2; PTPRC; PTPRJ; PXN; RAP1A; RAP1B; RUNX1; STAT5A; STAT5B; YES1; ZYX; LAMA3; INS; CLU; BSG; GSN; FTH1; MST1; LRP1; VTN; PGM1; NF1; AP2A1; ARF1; CAPN2; CTTN; DNM1; DNM2; MMP3; RAB11A; SDCBP; SPAG9; |

| Glypican pathway | 85 | 1335 | 8.83 × 10−6 | 0.014723522 | 0.000226516 | 0.000998777 | CLTA; CEBPZ; AHSG; COL1A1; FGG; FGA; FGB; ITGA6; TLN1; TYK2; GSK3B; MDM4; GAB1; DMP1; TIAM1; ITGAE; ACTN1; MED1; ALDH9A1; ARPC1B; ARPC2; ARPC3; BAIAP2; CALM1; CALM2; CALM3; CDC42; CDH1; CLIP1; COL1A2; CSF1R; CSK; CTNNB1; FN1; FYN; GNA13; GNAI1; GNAO1; HSPA1A; HSPA1B; ICAM1; ITGA2B; ITGB1; ITGB3; LIMA1; MMP2; NCKAP1; NDRG1; NFKB2; PGK1; PPP2R1A; PPP5C; PRKCD; PTK2; PTPRC; PTPRJ; PXN; RAP1A; RAP1B; RUNX1; STAT5A; STAT5B; YES1; ZYX; LAMA3; INS; CLU; SERPINC1; GSN; FTH1; MST1; LRP1; VTN; SHH; PGM1; NF1; AP2A1; ARF1; CAPN2; CTTN; DNM1; DNM2; MMP3; RAB11A; SPAG9; |

| PAR1-mediated thrombin signaling events | 85 | 1296 | 2.55 × 10−6 | 0.004258985 | 0.000151778 | 0.000669234 | CLTA; CEBPZ; F2; AHSG; COL1A1; FGG; FGA; FGB; ITGA6; TLN1; TYK2; GSK3B; MDM4; GAB1; DMP1; TIAM1; ITGAE; ACTN1; MED1; ALDH9A1; ARPC1B; ARPC2; ARPC3; BAIAP2; CALM1; CALM2; CALM3; CDC42; CDH1; CLIP1; COL1A2; CSF1R; CSK; CTNNB1; FN1; FYN; GNA13; GNAI1; GNAO1; HSPA1A; HSPA1B; ICAM1; ITGA2B; ITGB1; ITGB3; LIMA1; MMP2; NCKAP1; NDRG1; NFKB2; PGK1; PLCB3; PPP2R1A; PPP5C; PRKCD; PTK2; PTPRC; PTPRJ; PXN; RAP1A; RAP1B; RUNX1; STAT5A; STAT5B; YES1; ZYX; LAMA3; INS; CLU; GSN; FTH1; MST1; LRP1; VTN; PGM1; NF1; AP2A1; ARF1; CAPN2; CTTN; DNM1; DNM2; MMP3; RAB11A; SPAG9; |

| Thrombin/protease-activated receptor (PAR) pathway | 85 | 1297 | 2.64 × 10−6 | 0.004401549 | 0.000151778 | 0.000669234 | CLTA; CEBPZ; F2; AHSG; COL1A1; FGG; FGA; FGB; ITGA6; TLN1; TYK2; GSK3B; MDM4; GAB1; DMP1; TIAM1; ITGAE; ACTN1; MED1; ALDH9A1; ARPC1B; ARPC2; ARPC3; BAIAP2; CALM1; CALM2; CALM3; CDC42; CDH1; CLIP1; COL1A2; CSF1R; CSK; CTNNB1; FN1; FYN; GNA13; GNAI1; GNAO1; HSPA1A; HSPA1B; ICAM1; ITGA2B; ITGB1; ITGB3; LIMA1; MMP2; NCKAP1; NDRG1; NFKB2; PGK1; PLCB3; PPP2R1A; PPP5C; PRKCD; PTK2; PTPRC; PTPRJ; PXN; RAP1A; RAP1B; RUNX1; STAT5A; STAT5B; YES1; ZYX; LAMA3; INS; CLU; GSN; FTH1; MST1; LRP1; VTN; PGM1; NF1; AP2A1; ARF1; CAPN2; CTTN; DNM1; DNM2; MMP3; RAB11A; SPAG9; |

| Alpha9 beta1 integrin signaling events | 85 | 1302 | 3.11 × 10−6 | 0.005184572 | 0.000167244 | 0.000737431 | CLTA; CEBPZ; AHSG; COL1A1; FGG; FGA; FGB; ITGA6; TLN1; TYK2; GSK3B; MDM4; GAB1; DMP1; TIAM1; ITGAE; ACTN1; MED1; ALDH9A1; ARPC1B; ARPC2; ARPC3; BAIAP2; CALM1; CALM2; CALM3; CDC42; CDH1; CLIP1; COL1A2; CSF1R; CSK; CTNNB1; FN1; FYN; GNA13; GNAI1; GNAO1; HSPA1A; HSPA1B; ICAM1; ITGA2B; ITGB1; ITGB3; LIMA1; MMP2; NCKAP1; NDRG1; NFKB2; PGK1; PPP2R1A; PPP5C; PRKCD; PTK2; PTPRC; PTPRJ; PXN; RAP1A; RAP1B; RUNX1; STAT5A; STAT5B; TNC; VCAM1; YES1; ZYX; LAMA3; INS; CLU; GSN; FTH1; MST1; LRP1; VTN; PGM1; NF1; AP2A1; ARF1; CAPN2; CTTN; DNM1; DNM2; MMP3; RAB11A; SPAG9; |

| Endothelins | 85 | 1304 | 3.32 × 10−6 | 0.005533176 | 0.000170224 | 0.000750571 | CLTA; CEBPZ; AHSG; COL1A1; FGG; FGA; FGB; ITGA6; TLN1; TYK2; GSK3B; MDM4; GAB1; DMP1; TIAM1; ITGAE; ACTN1; MED1; ALDH9A1; ARPC1B; ARPC2; ARPC3; BAIAP2; CALM1; CALM2; CALM3; CDC42; CDH1; CLIP1; COL1A2; COL3A1; CSF1R; CSK; CTNNB1; FN1; FYN; GNA13; GNAI1; GNAO1; HSPA1A; HSPA1B; ICAM1; ITGA2B; ITGB1; ITGB3; LIMA1; MMP2; NCKAP1; NDRG1; NFKB2; PGK1; PLCB3; PPP2R1A; PPP5C; PRKCD; PTK2; PTPRC; PTPRJ; PXN; RAP1A; RAP1B; RUNX1; STAT5A; STAT5B; YES1; ZYX; LAMA3; INS; CLU; GSN; FTH1; MST1; LRP1; VTN; PGM1; NF1; AP2A1; ARF1; CAPN2; CTTN; DNM1; DNM2; MMP3; RAB11A; SPAG9; |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Al-Mahrouqi, N.; Al-Sayegh, H.; Al-Zadjali, S.; Khan, A.A. Extracellular Vesicle Associated Proteomic Biomarkers in Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cells 2026, 15, 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030231

Al-Mahrouqi N, Al-Sayegh H, Al-Zadjali S, Khan AA. Extracellular Vesicle Associated Proteomic Biomarkers in Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cells. 2026; 15(3):231. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030231

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Mahrouqi, Nahad, Hasan Al-Sayegh, Shoaib Al-Zadjali, and Aafaque Ahmad Khan. 2026. "Extracellular Vesicle Associated Proteomic Biomarkers in Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Cells 15, no. 3: 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030231

APA StyleAl-Mahrouqi, N., Al-Sayegh, H., Al-Zadjali, S., & Khan, A. A. (2026). Extracellular Vesicle Associated Proteomic Biomarkers in Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cells, 15(3), 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15030231