Preserved Function of Endothelial Colony-Forming Cells in Female Rats with Intrauterine Growth Restriction: Protection Against Arterial Hypertension and Arterial Stiffness?

Highlights

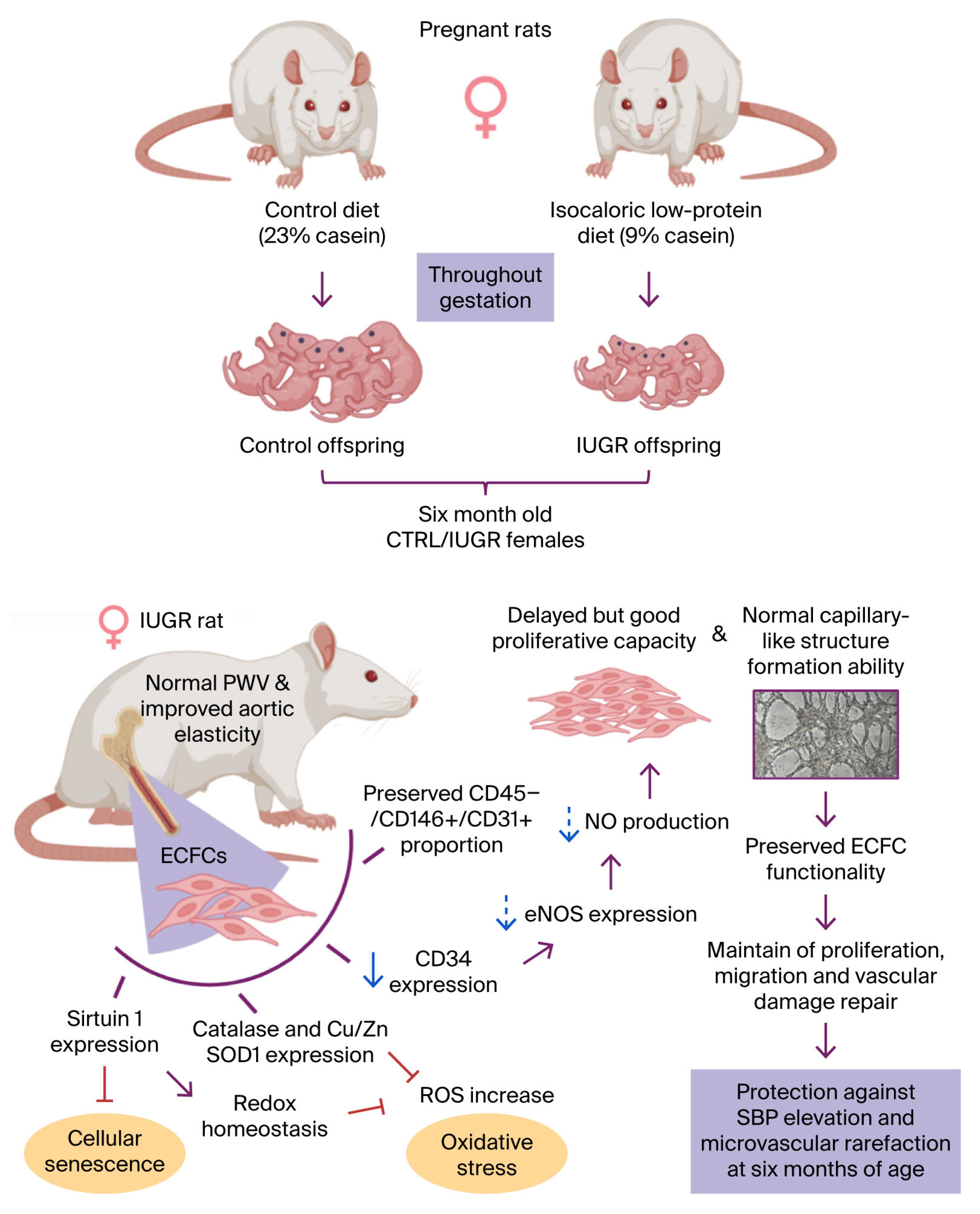

- Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) is a risk factor for long-term vascular outcomes.

- A sexual dimorphism has been identified: compared to control, only IUGR male rats displayed vascular dysfunctions at 6 months of age.

- IUGR female rats show only minor changes in endothelial colony forming cells (ECFCs) functions.

- The absence of ECFC alterations could protect IUGR females against vascular dysfunctions.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Model

2.2. Assessment of Pulse Wave Velocity (PWV)

2.3. Arterial Stiffness Evaluation

2.4. Isolation of ECFCs

2.5. ECFC Quantification Using Flow Cytometry

2.6. CD34 Expression Measurement by Immunofluorescence

2.7. ECFC Proliferation Test

2.8. Capillary-like Structure Formation

2.9. Measurement of NO Production

2.10. Measurement of Superoxide Anion Production

2.11. Protein Expression by Western Blotting

2.12. Senescence Detection in ECFCs

2.13. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of Arterial Stiffness

3.2. ECFC Quantification and Phenotyping

3.3. ECFC Function

3.3.1. Proliferation Capacity

3.3.2. Capillary-like Outgrowth Development

3.4. NO Pathway

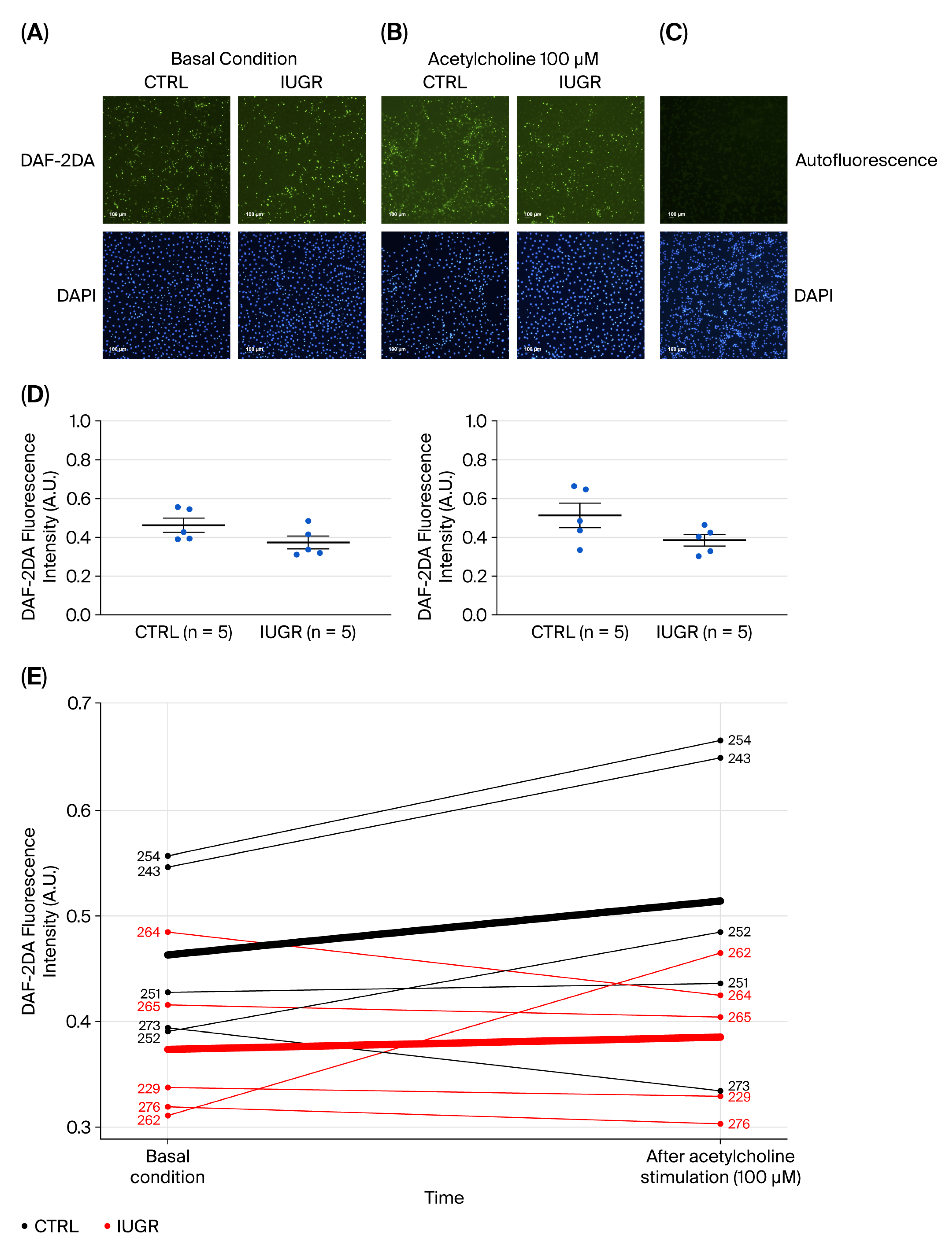

3.4.1. NO Production

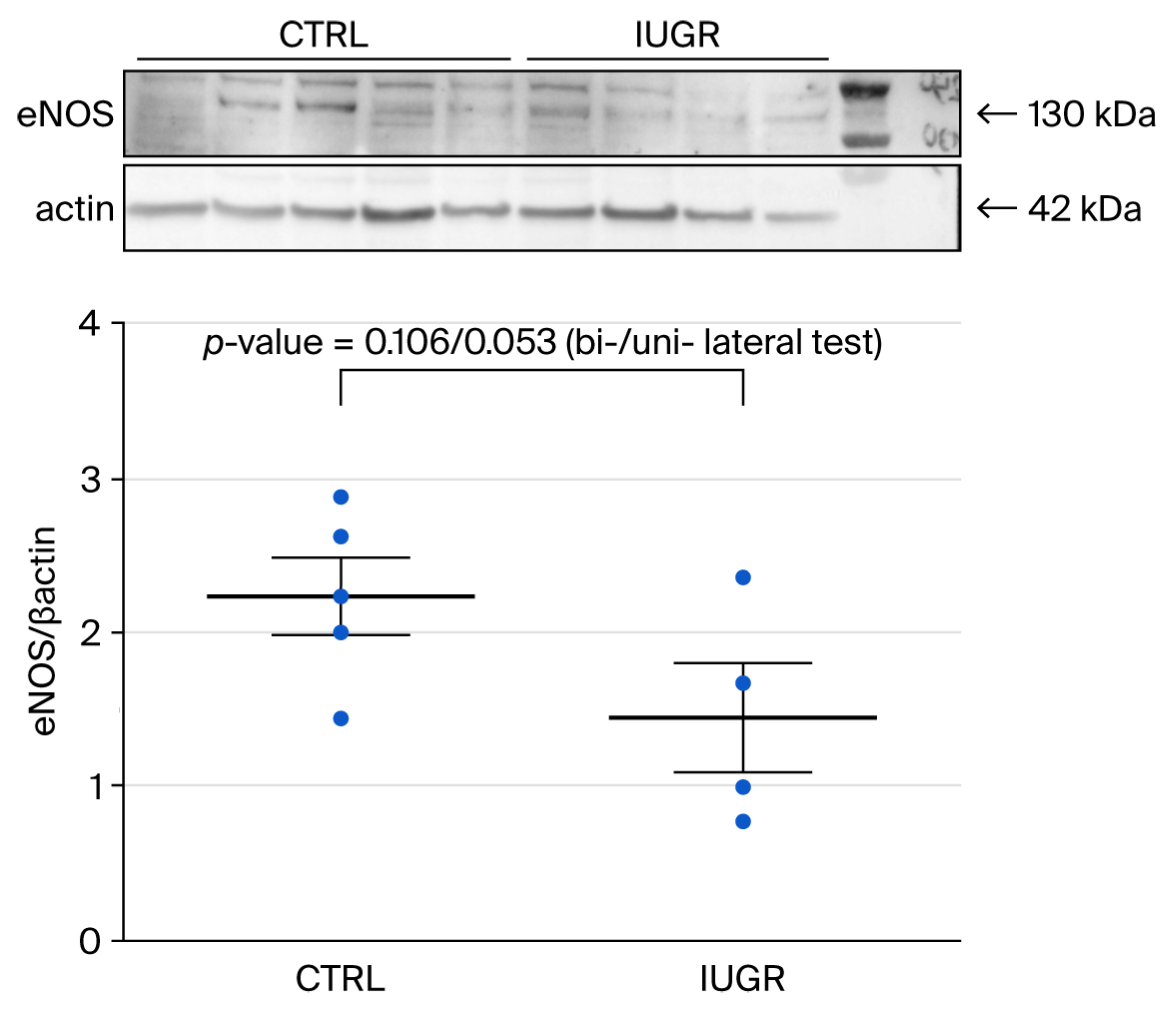

3.4.2. eNOS Expression

3.5. Processes Influencing Number and Function of ECFCs

3.5.1. Oxidative Stress

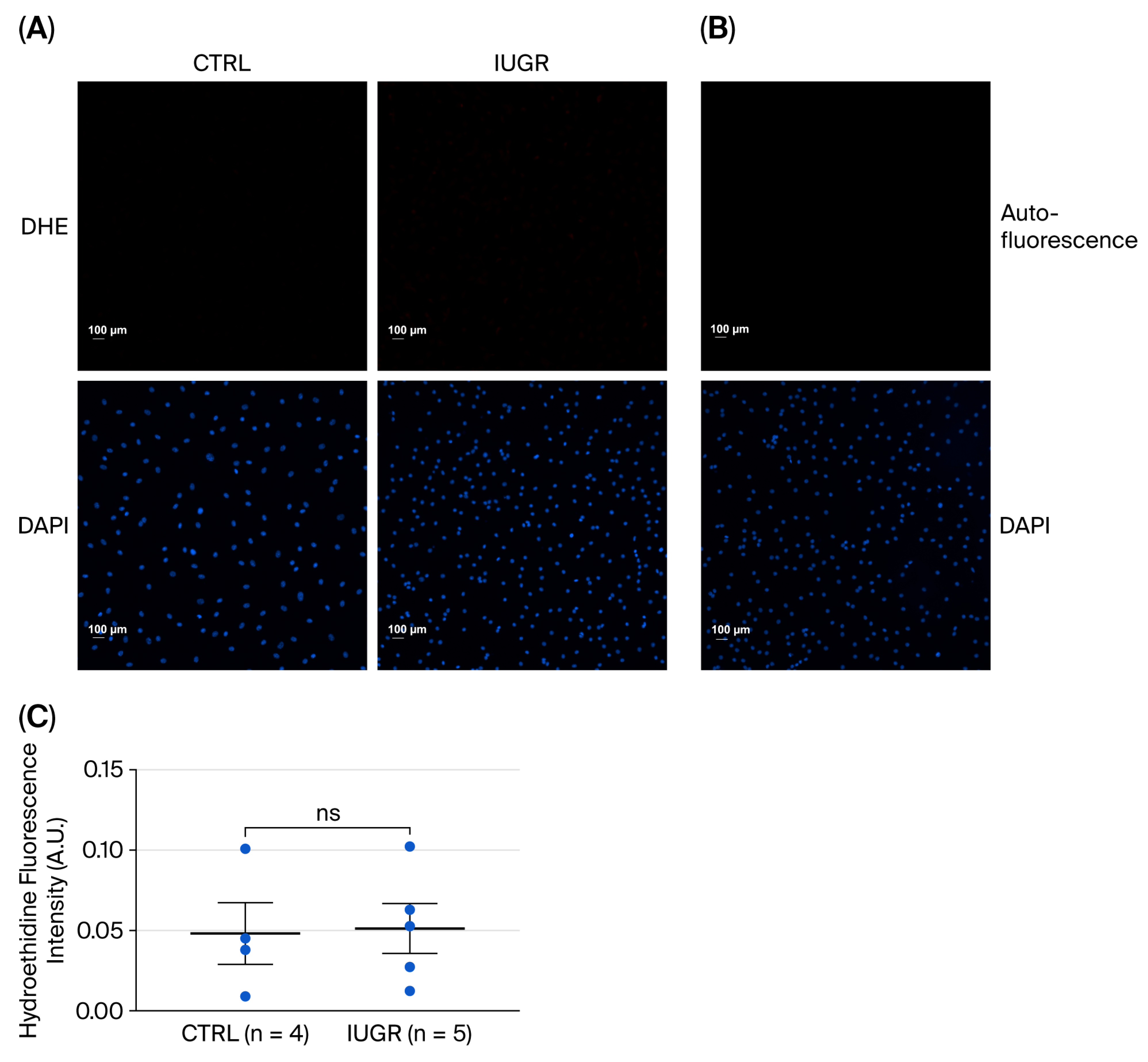

Superoxide Anion Production

Antioxidant Defenses

3.5.2. Cellular Senescence

β-Galactosidase Activity

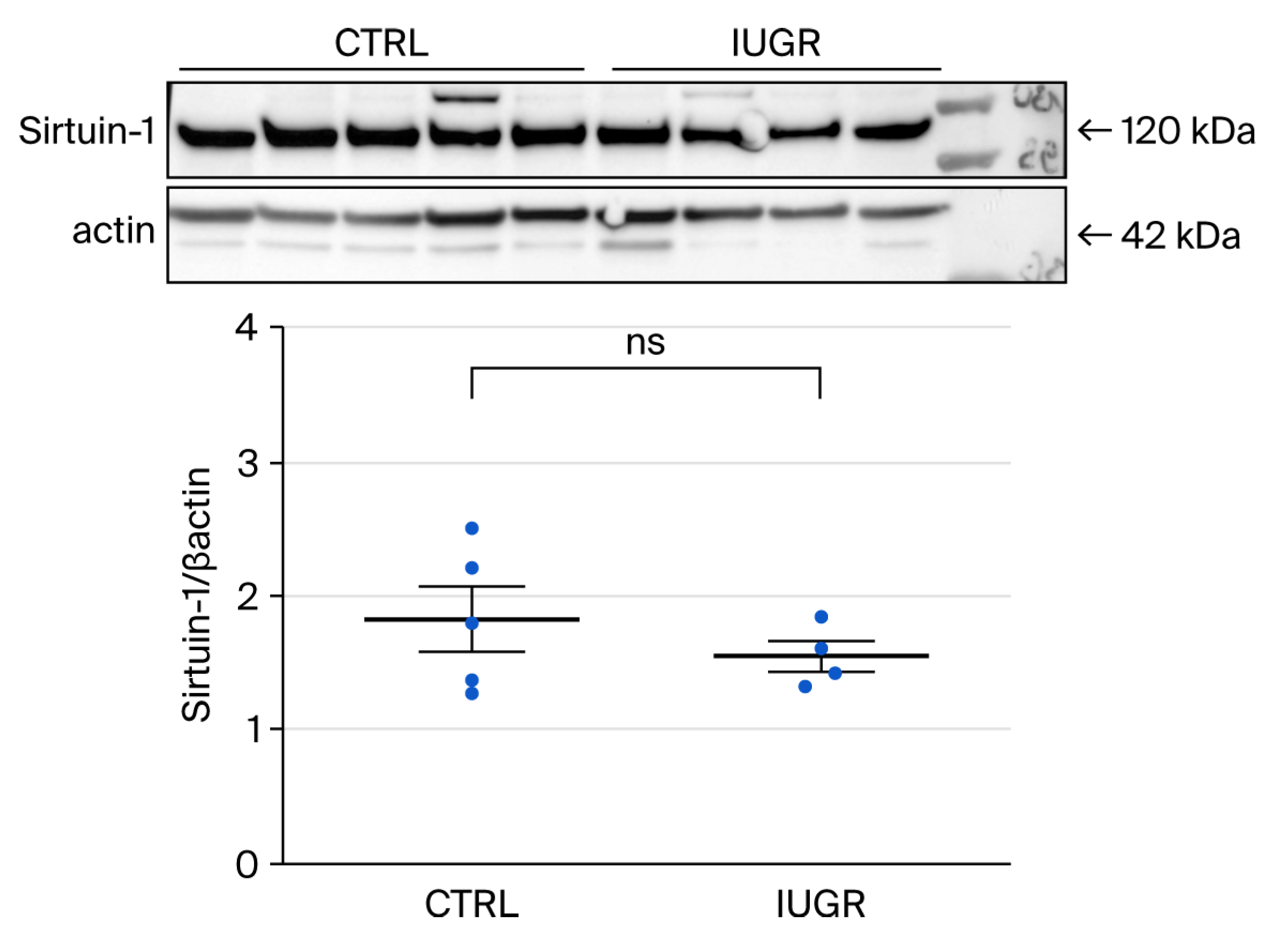

Sirtuin-1 Expression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

7. Translational Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHT | Arterial hypertension |

| BrdU | 5′-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine |

| CTRL | Control |

| DAF-2DA | 4,5-Diaminofluorescein diacetate |

| DHE | Dihydroethidine |

| EBM2 | Endothelial basal cell growth culture medium-2 |

| ECFCs | Endothelial colony-forming cells |

| ECG | Electrocardiography |

| eNOS | Endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| EPCs | Endothelial progenitor cells |

| FCS | Fetal calf serum |

| HEPES | 4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid |

| IUGR | Intrauterine growth restriction |

| MNCs | Mononuclear cells |

| MV2 | Endothelial cell growth medium |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PWV | Pulse wave velocity |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

| SIPS | Stress-induced premature senescence |

| SOD1 | Cu/Zn Superoxide dismutase |

| VEGFR-2 | Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 |

References

- Neves, M.F.; Kasal, D.A.; Cunha, A.R.; Medeiros, F. Vascular dysfunction as target organ damage in animal models of hypertension. Int. J. Hypertens. 2012, 2012, 187526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomiyama, H.; Ishizu, T.; Kohro, T.; Matsumoto, C.; Higashi, Y.; Takase, B.; Suzuki, T.; Ueda, S.; Yamazaki, T.; Furumoto, T.; et al. Longitudinal association among endothelial function, arterial stiffness and subclinical organ damage in hypertension. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018, 253, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.L. Arterial stiffness and hypertension. Clin. Hypertens. 2023, 29, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingram, D.A.; Mead, L.E.; Moore, D.B.; Woodard, W.; Fenoglio, A.; Yoder, M.C. Vessel wall-derived endothelial cells rapidly proliferate because they contain a complete hierarchy of endothelial progenitor cells. Blood 2005, 105, 2783–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Li, Z.; Zhang, W.; Du, Z.; Liu, K.; Yang, D.; Gong, S. Isolation and characterization of endothelial colony-forming cells from mononuclear cells of rat bone marrow. Exp. Cell Res. 2018, 370, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asahara, T.; Kawamoto, A.; Masuda, H. Concise review: Circulating endothelial progenitor cells for vascular medicine. Stem Cells 2011, 29, 1650–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina, R.J.; Barber, C.L.; Sabatier, F.; Dignat-George, F.; Melero-Martin, J.M.; Khosrotehrani, K.; Ohneda, O.; Randi, A.M.; Chan, J.K.Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; et al. Endothelial Progenitors: A Consensus Statement on Nomenclature. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2017, 6, 1316–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasev, D.; Koolwijk, P.; van Hinsbergh, V.W. Therapeutic Potential of Human-Derived Endothelial Colony-Forming Cells in Animal Models. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2016, 22, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, R.J.; O’Neill, C.L.; Humphreys, M.W.; Gardiner, T.A.; Stitt, A.W. Outgrowth endothelial cells: Characterization and their potential for reversing ischemic retinopathy. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 5906–5913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanpour, M.; Salybekov, A.A.; Kobayashi, S.; Asahara, T. CD34 positive cells as endothelial progenitor cells in biology and medicine. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1128134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldicke, T.; Tesar, M.; Griesel, C.; Rohde, M.; Grone, H.J.; Waltenberger, J.; Kollet, O.; Lapidot, T.; Yayon, A.; Weich, H. Anti-VEGFR-2 scFvs for cell isolation. Single-chain antibodies recognizing the human vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2/flk-1) on the surface of primary endothelial cells and preselected CD34+ cells from cord blood. Stem Cells 2001, 19, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligi, I.; Simoncini, S.; Tellier, E.; Vassallo, P.F.; Sabatier, F.; Guillet, B.; Lamy, E.; Sarlon, G.; Quemener, C.; Bikfalvi, A.; et al. A switch toward angiostatic gene expression impairs the angiogenic properties of endothelial progenitor cells in low birth weight preterm infants. Blood 2011, 118, 1699–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakogiannis, C.; Tousoulis, D.; Androulakis, E.; Briasoulis, A.; Papageorgiou, N.; Vogiatzi, G.; Kampoli, A.M.; Charakida, M.; Siasos, G.; Latsios, G.; et al. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells as biomarkers for prediction of cardiovascular outcomes. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012, 19, 2597–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, G.; Tao, J. Endothelial progenitor cells in cardiovascular diseases. Aging Med. 2018, 1, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.M.; Zalos, G.; Halcox, J.P.; Schenke, W.H.; Waclawiw, M.A.; Quyyumi, A.A.; Finkel, T. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells, vascular function, and cardiovascular risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, R.; Fukuda, N.; Katakawa, M.; Tsunemi, A.; Tahira, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; Ueno, T.; Soma, M. Effects of an angiotensin II receptor blocker on the impaired function of endothelial progenitor cells in patients with essential hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 2014, 27, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lineen, J.R.; Kuliszewski, M.; Dacouris, N.; Liao, C.; Rudenko, D.; Deva, D.P.; Goldstein, M.; Leong-Poi, H.; Wald, R.; Yan, A.T.; et al. Early outgrowth pro-angiogenic cell number and function do not correlate with left ventricular structure and function in conventional hemodialysis patients: A cross-sectional study. Can. J. Kidney Health Dis. 2015, 2, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.W.; Huang, P.H.; Huang, S.S.; Leu, H.B.; Huang, C.C.; Wu, T.C.; Chen, J.W.; Lin, S.J. Decreased circulating endothelial progenitor cell levels and function in essential hypertensive patients with electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy. Hypertens. Res. 2011, 34, 999–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassano, V.; Tripepi, G.; Perticone, M.; Miceli, S.; Scopacasa, I.; Armentaro, G.; Greco, M.; Maio, R.; Hribal, M.L.; Sesti, G.; et al. Endothelial progenitor cells predict vascular damage progression in naive hypertensive patients according to sex. Hypertens. Res. 2021, 44, 1451–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marketou, M.E.; Kalyva, A.; Parthenakis, F.I.; Pontikoglou, C.; Maragkoudakis, S.; Kontaraki, J.E.; Chlouverakis, G.; Zacharis, E.A.; Patrianakos, A.; Papadaki, H.A.; et al. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells in hypertensive patients with increased arterial stiffness. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2014, 16, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispi, F.; Miranda, J.; Gratacos, E. Long-term cardiovascular consequences of fetal growth restriction: Biology, clinical implications, and opportunities for prevention of adult disease. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, S869–S879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battista, M.C.; Oligny, L.L.; St-Louis, J.; Brochu, M. Intrauterine growth restriction in rats is associated with hypertension and renal dysfunction in adulthood. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 283, E124–E131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, T.; Murai-Takeda, A.; Kawabe, H.; Itoh, H. Low birth weight trends: Possible impacts on the prevalences of hypertension and chronic kidney disease. Hypertens. Res. 2020, 43, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martyn, C.N.; Greenwald, S.E. Impaired synthesis of elastin in walls of aorta and large conduit arteries during early development as an initiating event in pathogenesis of systemic hypertension. Lancet 1997, 350, 953–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tauzin, L.; Rossi, P.; Giusano, B.; Gaudart, J.; Boussuges, A.; Fraisse, A.; Simeoni, U. Characteristics of arterial stiffness in very low birth weight premature infants. Pediatr. Res. 2006, 60, 592–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, H.; Gazelius, B.; Norman, M. Impaired acetylcholine-induced vascular relaxation in low birth weight infants: Implications for adult hypertension? Pediatr. Res. 2000, 47, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeson, C.P.; Whincup, P.H.; Cook, D.G.; Donald, A.E.; Papacosta, O.; Lucas, A.; Deanfield, J.E. Flow-mediated dilation in 9- to 11-year-old children: The influence of intrauterine and childhood factors. Circulation 1997, 96, 2233–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertagnolli, M.; Xie, L.F.; Paquette, K.; He, Y.; Cloutier, A.; Fernandes, R.O.; Beland, C.; Sutherland, M.R.; Delfrate, J.; Curnier, D.; et al. Endothelial Colony-Forming Cells in Young Adults Born Preterm: A Novel Link Between Neonatal Complications and Adult Risks for Cardiovascular Disease. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassallo, P.F.; Simoncini, S.; Ligi, I.; Chateau, A.L.; Bachelier, R.; Robert, S.; Morere, J.; Fernandez, S.; Guillet, B.; Marcelli, M.; et al. Accelerated senescence of cord blood endothelial progenitor cells in premature neonates is driven by SIRT1 decreased expression. Blood 2014, 123, 2116–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guvendag Guven, E.S.; Karcaaltincaba, D.; Kandemir, O.; Kiykac, S.; Mentese, A. Cord blood oxidative stress markers correlate with umbilical artery pulsatility in fetal growth restriction. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013, 26, 576–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, B.M.; Cook, L.G.; Danchuk, S.; Puschett, J.B. Uncoupled endothelial nitric oxide synthase and oxidative stress in a rat model of pregnancy-induced hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 2007, 20, 1297–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imanishi, T.; Hano, T.; Nishio, I. Angiotensin II accelerates endothelial progenitor cell senescence through induction of oxidative stress. J. Hypertens. 2005, 23, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imanishi, T.; Tsujioka, H.; Akasaka, T. Endothelial progenitor cells dysfunction and senescence: Contribution to oxidative stress. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2008, 4, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, M.; Ishikawa, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Itoh, T.; Minami, Y.; Nakamura, M. Association between oxidative DNA damage and telomere shortening in circulating endothelial progenitor cells obtained from metabolic syndrome patients with coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 2008, 198, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thum, T.; Fraccarollo, D.; Galuppo, P.; Tsikas, D.; Frantz, S.; Ertl, G.; Bauersachs, J. Bone marrow molecular alterations after myocardial infarction: Impact on endothelial progenitor cells. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006, 70, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simoncini, S.; Coppola, H.; Rocca, A.; Bachmann, I.; Guillot, E.; Zippo, L.; Dignat-George, F.; Sabatier, F.; Bedel, R.; Wilson, A.; et al. Endothelial Colony-Forming Cells Dysfunctions Are Associated with Arterial Hypertension in a Rat Model of Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, H.; Al-Khalidi, K.; Gremlich, S.; Viertl, D.; Simeoni, U.; Armengaud, J.B.; Yzydorczyk, C. The hidden impact of intrauterine growth restriction in the pathogenesis of metabolic syndrome: Functional and structural alterations in rat visceral adipose tissue. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2026, 147, 110096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mivelaz, Y.; Yzydorczyk, C.; Barbier, A.; Cloutier, A.; Fouron, J.C.; de Blois, D.; Nuyt, A.M. Neonatal oxygen exposure leads to increased aortic wall stiffness in adult rats: A Doppler ultrasound study. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2011, 2, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Fu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Xing, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Yuan, L.; Gao, F. A novel methodology for rat aortic pulse wave velocity assessment by Doppler ultrasound: Validation against invasive measurements. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2019, 317, H1376–H1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bensley, J.G.; De Matteo, R.; Harding, R.; Black, M.J. Preterm birth with antenatal corticosteroid administration has injurious and persistent effects on the structure and composition of the aorta and pulmonary artery. Pediatr. Res. 2012, 71, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyard, F.; Yzydorczyk, C.; Castro, M.M.; Cloutier, A.; Bertagnolli, M.; Sartelet, H.; Germain, N.; Comte, B.; Schulz, R.; DeBlois, D.; et al. Remodeling of aorta extracellular matrix as a result of transient high oxygen exposure in newborn rats: Implication for arterial rigidity and hypertension risk. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smadja, D.M.; Melero-Martin, J.M.; Eikenboom, J.; Bowman, M.; Sabatier, F.; Randi, A.M. Standardization of methods to quantify and culture endothelial colony-forming cells derived from peripheral blood: Position paper from the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis SSC. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2019, 17, 1190–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauge, L.; Sabatier, F.; Boutouyrie, P.; D’Audigier, C.; Peyrard, S.; Bozec, E.; Blanchard, A.; Azizi, M.; Dizier, B.; Dignat-George, F.; et al. Forearm ischemia decreases endothelial colony-forming cell angiogenic potential. Cytotherapy 2014, 16, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandvuillemin, I.; Buffat, C.; Boubred, F.; Lamy, E.; Fromonot, J.; Charpiot, P.; Simoncini, S.; Sabatier, F.; Dignat-George, F.; Peyter, A.C.; et al. Arginase upregulation and eNOS uncoupling contribute to impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation in a rat model of intrauterine growth restriction. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2018, 315, R509–R520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debacq-Chainiaux, F.; Erusalimsky, J.D.; Campisi, J.; Toussaint, O. Protocols to detect senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (SA-betagal) activity, a biomarker of senescent cells in culture and in vivo. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 1798–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, G.M.G. Linear Mixed Models in Practice; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1997; p. 306. [Google Scholar]

- Taffé, P. Probabilité et Statistique Pour les Sciences de la Santé: Apprentissage au Moyen du Logiciel Stata; Stata Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2014; p. 559. [Google Scholar]

- Keshavjee, B.; Lambelet, V.; Coppola, H.; Viertl, D.; Prior, J.O.; Kappeler, L.; Armengaud, J.B.; Chouraqui, J.P.; Chehade, H.; Vanderriele, P.E.; et al. Stress-Induced Premature Senescence Related to Oxidative Stress in the Developmental Programming of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in a Rat Model of Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komnenov, D.; Rossi, N.F. Fructose-induced salt-sensitive blood pressure differentially affects sympathetically mediated aortic stiffness in male and female Sprague-Dawley rats. Physiol. Rep. 2023, 11, e15687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallinhart, P.E.; Lee, Y.U.; Lee, A.; Anghelescu, M.; Tonniges, J.R.; Calomeni, E.; Agarwal, G.; Lincoln, J.; Trask, A.J. Dissociation of pulse wave velocity and aortic wall stiffness in diabetic db/db mice: The influence of blood pressure. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1154454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagenseil, J.E.; Mecham, R.P. Elastin in large artery stiffness and hypertension. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2012, 5, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schank, J.C.; McClintock, M.K. A coupled-oscillator model of ovarian-cycle synchrony among female rats. J. Theor. Biol. 1992, 157, 317–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.D.; Kapadia, P.; Spiegel, J.; Cullen, A.E.; LaFarga, J.; Walker, A.E. The impact of age and sex on cerebral and large artery stiffness and the response to pulse pressure. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2025, 329, H1594–H1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendergast, B.J.; Onishi, K.G.; Zucker, I. Female mice liberated for inclusion in neuroscience and biomedical research. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014, 40, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalley, T.; Dubi, M.; Fumeaux, L.; Merli, M.S.; Sarre, A.; Schaer, N.; Simeoni, U.; Yzydorczyk, C. Sexual Dimorphism in Cardiometabolic Diseases: From Development to Senescence and Therapeutic Approaches. Cells 2025, 14, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingram, D.A.; Mead, L.E.; Tanaka, H.; Meade, V.; Fenoglio, A.; Mortell, K.; Pollok, K.; Ferkowicz, M.J.; Gilley, D.; Yoder, M.C. Identification of a novel hierarchy of endothelial progenitor cells using human peripheral and umbilical cord blood. Blood 2004, 104, 2752–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estes, M.L.; Mund, J.A.; Ingram, D.A.; Case, J. Identification of endothelial cells and progenitor cell subsets in human peripheral blood. Curr. Protoc. Cytom. 2010, 52, 9–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, C.C.; Cazzola, M.; De Fabritiis, P.; De Vincentiis, A.; Gianni, A.M.; Lanza, F.; Lauria, F.; Lemoli, R.M.; Tarella, C.; Zanon, P.; et al. CD34-positive cells: Biology and clinical relevance. Haematologica 1995, 80, 367–387. [Google Scholar]

- Asahara, T.; Murohara, T.; Sullivan, A.; Silver, M.; van der Zee, R.; Li, T.; Witzenbichler, B.; Schatteman, G.; Isner, J.M. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science 1997, 275, 964–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xiao, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Cui, Y.; Hao, H.; Wang, M.; Cowan, P.J.; Korthuis, R.J.; Li, G.; Sun, Q.; et al. Circulating Endothelial Progenitor Cells Are Preserved in Female Mice Exposed to Ambient Fine Particulate Matter Independent of Estrogen. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroncek, J.D.; Grant, B.S.; Brown, M.A.; Povsic, T.J.; Truskey, G.A.; Reichert, W.M. Comparison of endothelial cell phenotypic markers of late-outgrowth endothelial progenitor cells isolated from patients with coronary artery disease and healthy volunteers. Tissue Eng. Part A 2009, 15, 3473–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoder, M.C. NO role in EPC function. Blood 2005, 105, 1846–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque Contreras, D.; Vargas Robles, H.; Romo, E.; Rios, A.; Escalante, B. The role of nitric oxide in the post-ischemic revascularization process. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006, 112, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, D.G.; Fukumura, D.; Jain, R.K. Role of eNOS in neovascularization: NO for endothelial progenitor cells. Trends Mol. Med. 2004, 10, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei, S.; Stewart, D.J. Overexpression of endothelial NO synthase induces angiogenesis in a co-culture model. Cardiovasc. Res. 2002, 55, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, A.; Singh, A.; Roy, A.; Mohanty, S.; Naik, N.; Kalaivani, M.; Ramakrishnan, L. Role of endothelial colony forming cells (ECFCs) Tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) in determining ECFCs functionality in coronary artery disease (CAD) patients. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Pittman, R.N.; Popel, A.S. Nitric oxide in the vasculature: Where does it come from and where does it go? A quantitative perspective. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2008, 10, 1185–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacza, Z.; Pankotai, E.; Csordas, A.; Gero, D.; Kiss, L.; Horvath, E.M.; Kollai, M.; Busija, D.W.; Szabo, C. Mitochondrial NO and reactive nitrogen species production: Does mtNOS exist? Nitric Oxide 2006, 14, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koller, A. Perspectives: Microvascular endothelial dysfunction and gender. Eur. Heart J. Suppl. 2014, 16, A16–A19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, C.; Trindade, F.; Ferreira, R.; Neves, J.S.; Leite-Moreira, A.; Amado, F.; Santos, M.; Nogueira-Ferreira, R. Sexual dimorphism in cardiac remodeling: The molecular mechanisms ruled by sex hormones in the heart. J. Mol. Med. 2022, 100, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, M.P.; Sinha, D.; Russell, K.S.; Collinge, M.; Fulton, D.; Morales-Ruiz, M.; Sessa, W.C.; Bender, J.R. Membrane estrogen receptor engagement activates endothelial nitric oxide synthase via the PI3-kinase-Akt pathway in human endothelial cells. Circ. Res. 2000, 87, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, J.A.; Martini, E.R.; Smith, M.M.; Brunt, V.E.; Kaplan, P.F.; Halliwill, J.R.; Minson, C.T. Short-term oral progesterone administration antagonizes the effect of transdermal estradiol on endothelium-dependent vasodilation in young healthy women. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011, 301, H1716–H1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strehlow, K.; Werner, N.; Berweiler, J.; Link, A.; Dirnagl, U.; Priller, J.; Laufs, K.; Ghaeni, L.; Milosevic, M.; Bohm, M.; et al. Estrogen increases bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cell production and diminishes neointima formation. Circulation 2003, 107, 3059–3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiberi, J.; Cesarini, V.; Stefanelli, R.; Canterini, S.; Fiorenza, M.T.; La Rosa, P. Sex differences in antioxidant defence and the regulation of redox homeostasis in physiology and pathology. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2023, 211, 111802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, M.J.; Nissim, A.; Knight, A.R.; Whiteman, M.; Haigh, R.; Winyard, P.G. Oxidative stress in autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 125, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, T.; Peterson, T.E.; Holmuhamedov, E.L.; Terzic, A.; Caplice, N.M.; Oberley, L.W.; Katusic, Z.S. Human endothelial progenitor cells tolerate oxidative stress due to intrinsically high expression of manganese superoxide dismutase. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004, 24, 2021–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barp, J.; Araujo, A.S.; Fernandes, T.R.; Rigatto, K.V.; Llesuy, S.; Bello-Klein, A.; Singal, P. Myocardial antioxidant and oxidative stress changes due to sex hormones. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2002, 35, 1075–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malorni, W.; Straface, E.; Matarrese, P.; Ascione, B.; Coinu, R.; Canu, S.; Galluzzo, P.; Marino, M.; Franconi, F. Redox state and gender differences in vascular smooth muscle cells. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Hao, Q.; Chen, H.; Cheng, X. Sirt1 Regulates Oxidative Stress in Oxygen-Glucose Deprived Hippocampal Neurons. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, C.K.; Chhabra, G.; Ndiaye, M.A.; Garcia-Peterson, L.M.; Mack, N.J.; Ahmad, N. The Role of Sirtuins in Antioxidant and Redox Signaling. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2018, 28, 643–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunelli, E.; Domanico, F.; La Russa, D.; Pellegrino, D. Sex differences in oxidative stress biomarkers. Curr. Drug Targets 2014, 15, 811–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Larrea, M.B.; Leal, A.M.; Martin, C.; Martinez, R.; Lacort, M. Antioxidant action of estrogens in rat hepatocytes. Rev. Esp. Fisiol. 1997, 53, 225–229. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Williams, D.; Walter, G.A.; Thompson, W.E.; Sidell, N. Estrogen increases Nrf2 activity through activation of the PI3K pathway in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2014, 328, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vina, J.; Borras, C.; Gambini, J.; Sastre, J.; Pallardo, F.V. Why females live longer than males? Importance of the upregulation of longevity-associated genes by oestrogenic compounds. FEBS Lett. 2005, 579, 2541–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, H.; Kim, M.K.; Iwakura, A.; Ii, M.; Thorne, T.; Qin, G.; Asai, J.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Sekiguchi, H.; Silver, M.; et al. Estrogen receptors alpha and beta mediate contribution of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells to functional recovery after myocardial infarction. Circulation 2006, 114, 2261–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwakura, A.; Shastry, S.; Luedemann, C.; Hamada, H.; Kawamoto, A.; Kishore, R.; Zhu, Y.; Qin, G.; Silver, M.; Thorne, T.; et al. Estradiol enhances recovery after myocardial infarction by augmenting incorporation of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells into sites of ischemia-induced neovascularization via endothelial nitric oxide synthase-mediated activation of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Circulation 2006, 113, 1605–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattagajasingh, I.; Kim, C.S.; Naqvi, A.; Yamamori, T.; Hoffman, T.A.; Jung, S.B.; DeRicco, J.; Kasuno, K.; Irani, K. SIRT1 promotes endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation by activating endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 14855–14860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.Y.; Han, J.A.; Im, J.S.; Morrone, A.; Johung, K.; Goodwin, E.C.; Kleijer, W.J.; DiMaio, D.; Hwang, E.S. Senescence-associated beta-galactosidase is lysosomal beta-galactosidase. Aging Cell 2006, 5, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, M.; Hazrati, L.N. Evidence of sex differences in cellular senescence. Neurobiol. Aging 2022, 120, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefzadeh, M.J.; Zhao, J.; Bukata, C.; Wade, E.A.; McGowan, S.J.; Angelini, L.A.; Bank, M.P.; Gurkar, A.U.; McGuckian, C.A.; Calubag, M.F.; et al. Tissue specificity of senescent cell accumulation during physiologic and accelerated aging of mice. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzeciak, A.R.; Barnes, J.; Ejiogu, N.; Foster, K.; Brant, L.J.; Zonderman, A.B.; Evans, M.K. Age, sex, and race influence single-strand break repair capacity in a human population. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 45, 1631–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torella, D.; Salerno, N.; Cianflone, E. Senescent cells enhance ischemic aging in the female heart. Aging 2023, 15, 2364–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwakura, A.; Luedemann, C.; Shastry, S.; Hanley, A.; Kearney, M.; Aikawa, R.; Isner, J.M.; Asahara, T.; Losordo, D.W. Estrogen-mediated, endothelial nitric oxide synthase-dependent mobilization of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells contributes to reendothelialization after arterial injury. Circulation 2003, 108, 3115–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faris, P.; Negri, S.; Perna, A.; Rosti, V.; Guerra, G.; Moccia, F. Therapeutic Potential of Endothelial Colony-Forming Cells in Ischemic Disease: Strategies to Improve their Regenerative Efficacy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, N.; Langford-Smith, A.W.W.; Wilkinson, F.L.; Alexander, M.Y. Endothelial Progenitor Cells: New Targets for Therapeutics for Inflammatory Conditions with High Cardiovascular Risk. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| IUGR Male Rats | IUGR Female Rats | ||

| × | Elevated systolic blood pressure. | √ | Normal systolic blood pressure. |

| × | Microvascular rarefaction. | √ | Absence of microvascular rarefaction. |

| ECFCs of IUGR Male Rats | ECFCs of IUGR Female Rats | ||

| × | Reduction of total number. | × | Slight alterations in CD34 expression. |

| × | Alteration in proliferation capacity. | √ | Delay in proliferation phase between 6 h and 24 h. |

| × | Altered ability to form capillary-like structures. | √ | Preserved ability to form capillary-like structures. |

| × | Reduction in NO production. | × | Slight reduction in NO levels and eNOS expression. |

| × | Presence of oxidative stress and SIPS markers. | √ | Absence of oxidative stress and SIPS markers. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chevalley, T.; Bertholet, F.; Dübi, M.; Merli, M.S.; Charmoy, M.; Bron, S.; Allouche, M.; Sarre, A.; Sekarski, N.; Simoncini, S.; et al. Preserved Function of Endothelial Colony-Forming Cells in Female Rats with Intrauterine Growth Restriction: Protection Against Arterial Hypertension and Arterial Stiffness? Cells 2026, 15, 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020171

Chevalley T, Bertholet F, Dübi M, Merli MS, Charmoy M, Bron S, Allouche M, Sarre A, Sekarski N, Simoncini S, et al. Preserved Function of Endothelial Colony-Forming Cells in Female Rats with Intrauterine Growth Restriction: Protection Against Arterial Hypertension and Arterial Stiffness? Cells. 2026; 15(2):171. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020171

Chicago/Turabian StyleChevalley, Thea, Floriane Bertholet, Marion Dübi, Maria Serena Merli, Mélanie Charmoy, Sybil Bron, Manon Allouche, Alexandre Sarre, Nicole Sekarski, Stéphanie Simoncini, and et al. 2026. "Preserved Function of Endothelial Colony-Forming Cells in Female Rats with Intrauterine Growth Restriction: Protection Against Arterial Hypertension and Arterial Stiffness?" Cells 15, no. 2: 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020171

APA StyleChevalley, T., Bertholet, F., Dübi, M., Merli, M. S., Charmoy, M., Bron, S., Allouche, M., Sarre, A., Sekarski, N., Simoncini, S., Taffé, P., Simeoni, U., & Yzydorczyk, C. (2026). Preserved Function of Endothelial Colony-Forming Cells in Female Rats with Intrauterine Growth Restriction: Protection Against Arterial Hypertension and Arterial Stiffness? Cells, 15(2), 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020171