Ginseng Polysaccharides Protect Against Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Induced Damage via PI3K/Akt Signalling Pathway in Bovine Ovarian Granulosa Cells

Highlights

- Ginseng polysaccharides protect ovarian granulosa cells by alleviating endoplasmic reticulum stress and inhibiting subsequent necroptosis via the RIPK3/MLKL pathway.

- The polysaccharides restore cellular proliferation and estrogen synthesis compromised by ERS, primarily through activation of the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway, a mechanism corroborated by in vivo studies.

- The study identifies ginseng polysaccharides as a promising natural agent for protecting ovarian function, offering a potential preventive or therapeutic strategy against ovarian disorders driven by endoplasmic reticulum stress and necroptosis, such as premature ovarian insufficiency.

- It establishes a clear molecular pathway where these polysaccharides alleviate ER stress, inhibit the downstream RIPK3/MLKL-mediated necroptosis, and activate pro-survival PI3K/Akt signalling to restore cell health, providing a validated target for future interventions.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Treatments

2.2. Chemicals and Reagents

2.3. Ovarian Granulosa Cell (GC) Culture and Treatment

2.4. RNA Extraction and Real Time-Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

2.5. CCK-8 Assay

2.6. 5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) Assay

2.7. Western Blotting Analysis

2.8. Flow Cytometry Assay

2.9. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) for Estrogen (E2)

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Ginseng Polysaccharides Inhibit Tm-Induced Necroptosis in Ovarian GCs

3.2. Ginseng Polysaccharides Alleviate Tm-Induced ERS

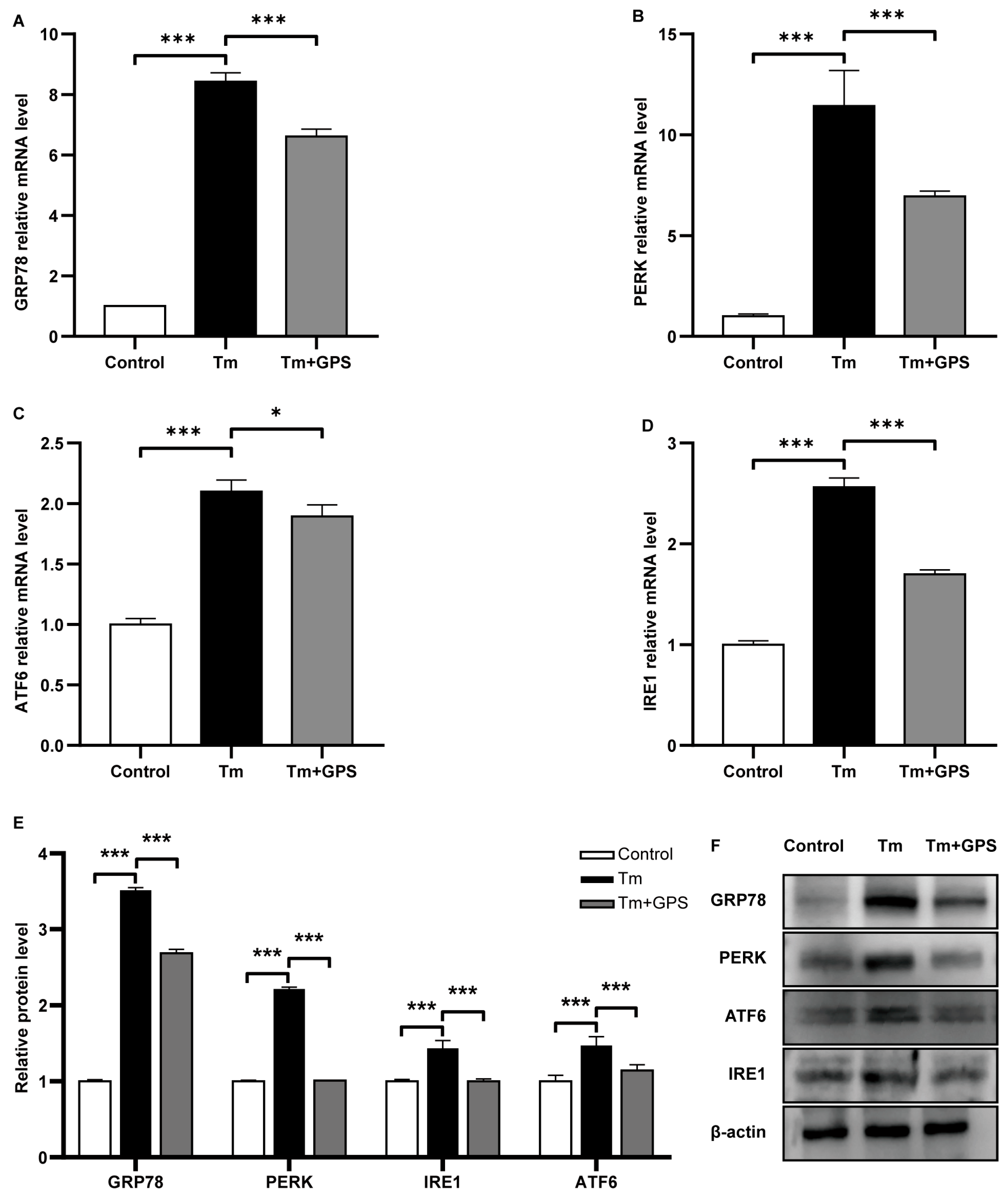

3.3. Ginseng Polysaccharides Alleviate Tm-Induced Impairment of Ovarian GC Proliferation via a PI3K/AKT-Dependent Mechanism

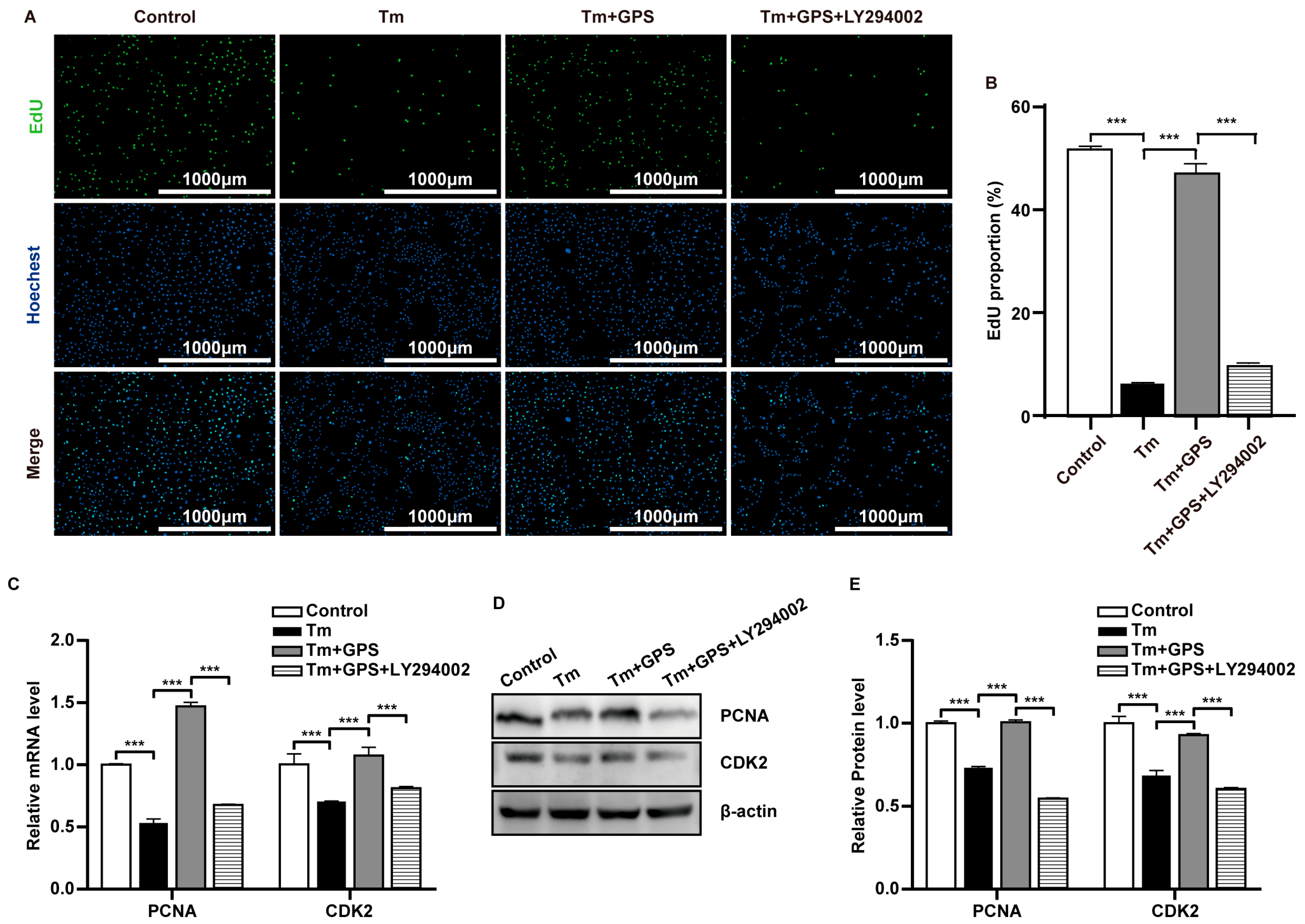

3.4. Ginseng Polysaccharides Prevent Tm-Induced Impairment of Estrogen Secretion via a PI3K/AKT-Dependent Mechanism

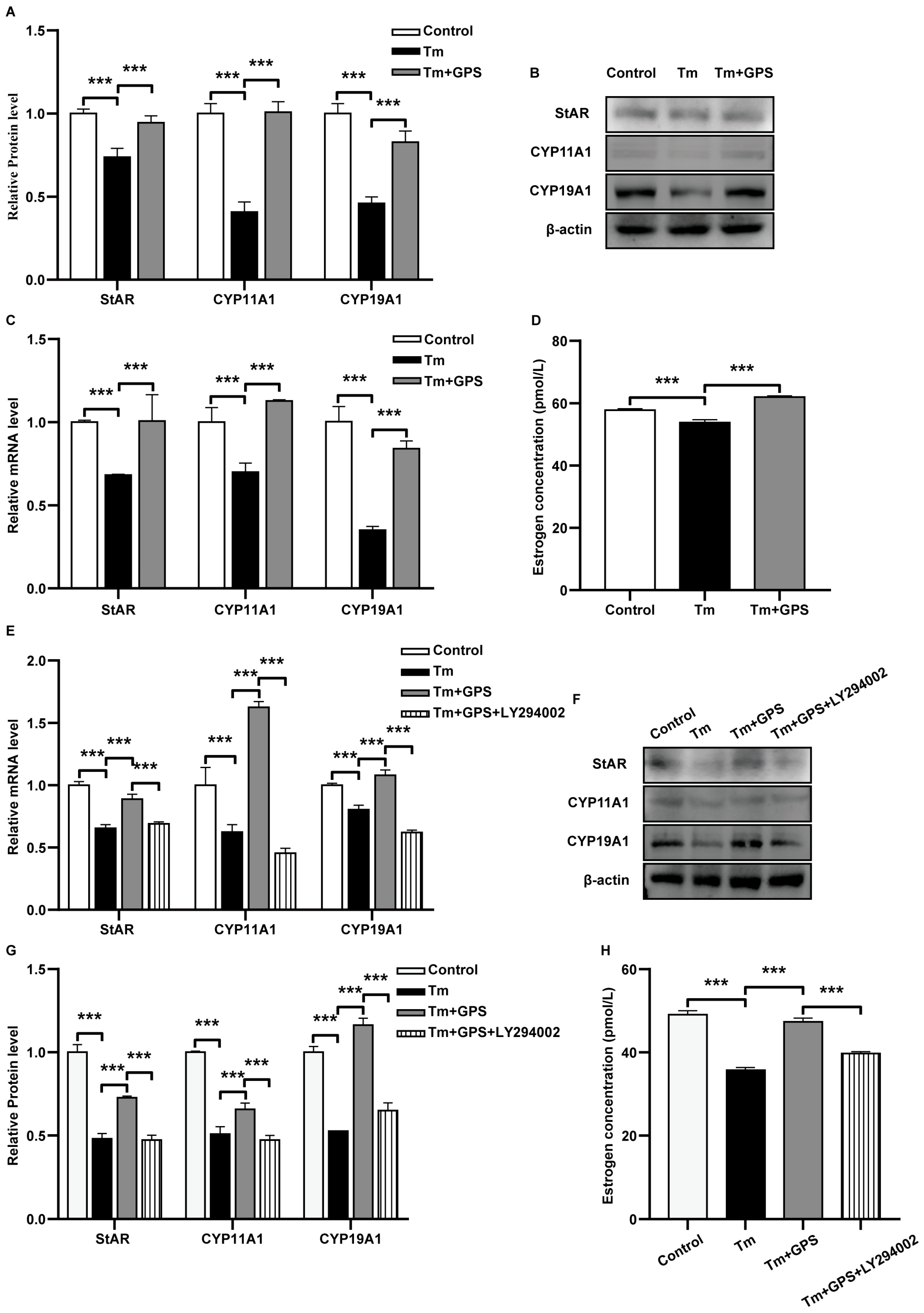

3.5. GPS Alleviates ER Stress-Induced Ovarian Injury In Vivo

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hammond, J.M.; Hsu, C.-J.; Mondschein, J.S.; Canning, S.F. PARACRINE AND AUTOCRINE FUNCTIONS OF GROWTH FACTORS IN THE OVARIAN FOLLICLE. J. Anim. Sci. 1988, 66, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manabe, N.; Goto, Y.; Matsuda-Minehata, F.; Inoue, N.; Maeda, A.; Sakamaki, K.; Miyano, T. Regulation Mechanism of Selective Atresia in Porcine Follicles: Regulation of Granulosa Cell Apoptosis During Atresia. J. Reprod. Dev. 2004, 50, 493–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecconi, S.; Ciccarelli, C.; Barberi, M.; Macchiarelli, G.; Canipari, R. Granulosa Cell-Oocyte Interactions. Eur. J. Obs. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2004, 115, S19–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.X.; Jiang, Z.Y.; Wu, Y.W.; Sha, Q.Q.; Liu, Y.; Ding, J.Y.; Xi, W.D.; Li, J.; Fan, H.Y. CNOT6/6L-Mediated mRNA Degradation in Ovarian Granulosa Cells Is a Key Mechanism of Gonadotropin-Triggered Follicle Development. Cell Rep. 2021, 37, 110007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, J.J.; Roche, J.F. Development of Nonovulatory Antral Follicles in Heifers: Changes in Steroids in Follicular Fluid and Receptors for Gonadotropins. Endocrinology 1983, 112, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.; Li, Y.; Song, D.; Ding, J.; Mei, S.; Sun, S.; Cheng, W.; Yu, J.; Zhou, L.; Kuang, Y.; et al. Iron-Overloaded Follicular Fluid Increases the Risk of Endometriosis-Related Infertility by Triggering Granulosa Cell Ferroptosis and Oocyte Dysmaturity. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Han, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhao, R.; Dai, S.; Guo, Y.; Li, N.; Yang, F.; Zeng, S. The Assembly and Activation of the PANoptosome Promote Porcine Granulosa Cell Programmed Cell Death during Follicular Atresia. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 15, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, G.R.; Yadav, P.K.; Yadav, A.K.; Tiwari, M.; Gupta, A.; Sharma, A.; Sahu, K.; Pandey, A.N.; Pandey, A.K.; Chaube, S.K. Necrosis and Necroptosis in Germ Cell Depletion from Mammalian Ovary. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 8019–8027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Cui, Z.; Li, C.; Lu, K.; Chen, K.; Cui, W.; Wu, Y.; Xia, D. Exposure to Perfluorodecanoic Acid Impairs Follicular Development via Inducing Granulosa Cell Necroptosis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 287, 117268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Gao, Q.; Wei, J.; Xie, W.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, Z.; Han, Y.; Weng, Q. Seasonal Changes in Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Ovarian Steroidogenesis in the Muskrats (Ondatra zibethicus). Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1123699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Q.; Lu, W.; Fan, S.; Xie, W.; Zhang, H.; Han, Y.; Weng, Q. Seasonal Changes in Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Steroidogenesis in the Ovary of the Wild Ground Squirrels (Citellus dauricus Brandt). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2023, 343, 114368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, M.; Takahashi, N.; Azhary, J.M.; Kunitomi, C.; Fujii, T.; Osuga, Y. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress: A Key Regulator of the Follicular Microenvironment in the Ovary. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 27, gaaa088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-F.; Liu, Y.; Zi, X.-D.; Li, H.; Lu, J.-Y.; Jing, T. Molecular Cloning, Sequence, and Expression Patterns of DNA Damage Induced Transcript 3 (DDIT3) Gene in Female Yaks (Bos grunniens). Anim. Biotechnol. 2023, 34, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Shen, R.; Song, R.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shi, H.; Kong, X.; Hua, Y.; Zhang, L. New Insights into the Tenderization Pattern of Yak Meat by ROS-ERS: Promotion of ERS-Associated Apoptosis through Feedback Regulation of PERK/IRE1/ATF6 and Caspase-12 Activity. Food Chem. 2025, 470, 142705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, W.; Jin, L.; Wu, C.; Liao, H.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, Z.; Han, W.; Chen, Q.; Ding, C. Treatment with FAP-Targeted Zinc Ferrite Nanoparticles for Rheumatoid Arthritis by Inducing Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Mitochondrial Damage. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 21, 100702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, M.; Feng, H.; Yao, Y.; Chen, R.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, C. Epigallocatechin Gallate Ameliorates Granulosa Cell Developmental via the Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2 Alpha/Activating Transcription Factor 4 Pathway in Hyperthyroid Female Rats. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Xu, G.; Wang, H.; Shu, X.; Ding, H.; Ma, X.; Guo, J.; Wang, J.; et al. Ameliorative Effect of Itaconic Acid/IRG1 Against Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Induced Necroptosis in Granulosa Cells via PERK-ATF4-AChE Pathway in Bovine. Cells 2025, 14, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.; Yu, Y.; Qiao, J. Dual Role for the Unfolded Protein Response in the Ovary: Adaption and Apoptosis. Protein Cell 2017, 8, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Chen, H.; Lin, P.; Wang, A.; Wang, L.; Jin, Y. ATF6 Knockdown Decreases Apoptosis, Arrests the S Phase of the Cell Cycle, and Increases Steroid Hormone Production in Mouse Granulosa Cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2017, 312, C341–C353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Lv, C.; Lu, J. Natural Occurring Polysaccharides from Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer: A Review of Isolation, Structures, and Bioactivities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 133, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Shao, S.; Wang, D.; Zhao, D.; Wang, M. Recent Progress in Polysaccharides from Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 494–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.-M.; Jiang, S.; Li, S.-S.; Sun, Y.-S.; Wang, S.-H.; Liu, W.-C.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.-P.; Zhang, R.; Li, W. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Activated PERK-eIF2α-ATF4 Signaling Pathway Is Involved in the Ameliorative Effects of Ginseng Polysaccharides against Cisplatin-Induced Nephrotoxicity in Mice. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 8958–8966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, H.; Han, Q.; Lan, J.; Chen, G.; Cao, G.; Yang, C. Effects of Astragalus and Ginseng Polysaccharides on Growth Performance, Immune Function and Intestinal Barrier in Weaned Piglets Challenged with Lipopolysaccharide. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2020, 104, 1096–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, C.; Qi, X.; Liu, X.; Hu, M.; Zhao, Q.; Guan, L.; Xu, L. Integrated Network Pharmacology, Molecular Docking and in Vivo Experiments to Elucidate the Extenuative Mechanisms of Ginseng Polysaccharide against Toxoplasma Gondii-Induced Testicular Toxicity. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 148, 114147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Sun, H.-M.; Wu, B.; Sun, T.-Y.; Han, L.-Z.; Wang, G.; Shang, Y.-F.; Yang, S.; Zhou, D.-S. Artesunate Delays the Dysfunction of Age-Related Intestinal Epithelial Barrier by Mitigating Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress/Unfolded Protein Response. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2023, 210, 111760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Aretia, D.; Hernández-Coronado, C.G.; Guzmán, A.; Medina-Moctezuma, Z.B.; Gutiérrez, C.G.; Rosales-Torres, A.M. Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Mediates FSH-Induced Cell Viability but Not Steroidogenesis in Bovine Granulosa Cells. Theriogenology 2024, 213, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Dong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ding, H.; Wang, J.; Zhao, J.; Liu, H.; Lv, W. Melatonin Attenuates Oxidative Stress-Induced Apoptosis of Bovine Ovarian Granulosa Cells by Promoting Mitophagy via SIRT1/FoxO1 Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Tan, W.; Li, W.; Li, W.; Zhu, S.; Zhong, J.; Shang, C.; Chen, Y. miR-1226-3p Promotes Sorafenib Sensitivity of Hepatocellular Carcinoma via Downregulation of DUSP4 Expression. J. Cancer 2019, 10, 2745–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.-M.; Wang, Z.; Li, S.-P.; Wang, M.; Yan, W.-T.; Liu, F.-X.; Wang, C.-D.; Zhang, X.-D.; Chen, D.; Yan, J.; et al. RIP3/MLKL-Mediated Neuronal Necroptosis Induced by Methamphetamine at 39 °C. Neural Regen. Res. 2020, 15, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Liu, J.; Cao, J.; Wang, G.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, S. Macrophage Infiltration Initiates RIP3/MLKL-Dependent Necroptosis in Paclitaxel-Induced Neuropathic Pain. Mediat. Inflamm. 2022, 2022, 1567210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, R.; Pal, R.; Ganguly, B.; Majhi, B.; Dutta, S. Mono-Quinoxaline-Induced DNA Structural Alteration Leads to ZBP1/RIP3/MLKL-Driven Necroptosis in Cancer Cells. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 270, 116377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Guo, J.; Yang, N.; Huang, Y.; Hu, T.; Rao, C. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Mediated Cell Death in Liver Injury. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Zhang, N.; Chen, S.; Hu, K.; Li, Y.; Fang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, L. Cadmium (Cd) and 2,2′,4,4′-Tetrabromodiphenyl Ether (BDE-47) Co-Exposure Induces Acute Kidney Injury through Oxidative Stress and RIPK3-Dependent Necroptosis. Environ. Toxicol. 2023, 38, 2332–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Sui, D.; Fu, W.; Sun, L.; Li, Y.; Yu, P.; Yu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, H. Protective Effects of Polysaccharides from Panax ginseng on Acute Gastric Ulcers Induced by Ethanol in Rats. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 2741–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-H.; Byon, Y.-Y.; Ko, E.-J.; Song, J.-Y.; Yun, Y.-S.; Shin, T.; Joo, H.-G. Immunomodulatory Activity of Ginsan, a Polysaccharide of Panax ginseng, on Dendritic Cells. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2009, 13, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-L.; Xi, Q.-Y.; Yang, L.; Li, H.-Y.; Jiang, Q.-Y.; Shu, G.; Wang, S.-B.; Gao, P.; Zhu, X.-T.; Zhang, Y.-L. The Effect of Dietary Panax ginseng Polysaccharide Extract on the Immune Responses in White Shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei. Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2011, 30, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Prisco, G.V.; Huang, W.; Buffington, S.A.; Hsu, C.-C.; Bonnen, P.E.; Placzek, A.N.; Sidrauski, C.; Krnjević, K.; Kaufman, R.J.; Walter, P.; et al. Translational Control of mGluR-Dependent Long-Term Depression and Object-Place Learning by eIF2α. Nat. Neurosci. 2014, 17, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, G.; Ragetli, R.; Mnich, K.; Doble, B.W.; Kammouni, W.; Logue, S.E. IRE1 Signaling Increases PERK Expression during Chronic ER Stress. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Hossain, M.M.; Read, D.E.; Hetz, C.; Samali, A.; Gupta, S. PERK Regulated miR-424(322)-503 Cluster Fine-Tunes Activation of IRE1 and ATF6 during Unfolded Protein Response. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 18304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Li, N.; Wang, T. PERK Prevents Rhodopsin Degradation during Retinitis Pigmentosa by Inhibiting IRE1-Induced Autophagy. J. Cell Biol. 2023, 222, e202208147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, M.; Moser, J.; Hoffman, T.E.; Watts, L.P.; Min, M.; Musteanu, M.; Rong, Y.; Ill, C.R.; Nangia, V.; Schneider, J.; et al. Rapid Adaptation to CDK2 Inhibition Exposes Intrinsic Cell-Cycle Plasticity. Cell 2023, 186, 2628–2643.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, M.; Pepperkok, R.; Lukas, J.; Baldin, V.; Ansorge, W.; Bartek, J.; Draetta, G. Regulation of the Cell Cycle by the Cdk2 Protein Kinase in Cultured Human Fibroblasts. J. Cell Biol. 1993, 121, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, P.R.; Allan, L.A. Cell-Cycle Control in the Face of Damage—A Matter of Life or Death. Trends Cell Biol. 2009, 19, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yuan, X.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Xu, L.; Wu, Y. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Mediated MDRV P10.8 Protein-Induced Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis Through the PERK/eIF2α Pathway. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Li, Q.; Cao, Y.; Shen, Y.; Chen, P.; Yan, J.; Li, J. Vitamin E Regulates Bovine Granulosa Cell Apoptosis via NRF2-Mediated Defence Mechanism by Activating PI3K/AKT and ERK1/2 Signalling Pathways. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2021, 56, 1066–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Pei, N.; Jia, H.; Yin, Y.; Xu, H.; Tian, T.; Liu, C.; Xu, L.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; et al. GAS1 Affects Proliferation, Apoptosis, and Steroid Hormone Levels by Regulating Mitochondrial Functions and the PI3K/AKT Pathway in Bovine Granulosa Cells. Theriogenology 2025, 248, 117597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, K.; Wang, X.; He, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Quan, F. The Wilms Tumor Gene (WT1) (+/-KTS) Isoforms Regulate Steroidogenesis by Modulating the PI3K/AKT and ERK1/2 Pathways in Bovine Granulosa Cells†. Biol. Reprod. 2019, 100, 1344–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhang, W.; Shi, X.; Xu, S. Di-(2-Ethyl Hexyl) Phthalate Induced Oxidative Stress Promotes Microplastics Mediated Apoptosis and Necroptosis in Mice Skeletal Muscle by Inhibiting PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway. Toxicology 2022, 474, 153226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Chang, X.; Zhu, H.; Wang, D.; Chen, G. PI3K Mediates Tumor Necrosis Factor Induced-Necroptosis through Initiating RIP1-RIP3-MLKL Signaling Pathway Activation. Cytokine 2020, 129, 155046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, K.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Shi, X.; Gong, D. The Antagonistic Effect of Melatonin on TBBPA-Induced Apoptosis and Necroptosis via PTEN/PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway in Swine Testis Cells. Environ. Toxicol. 2022, 37, 2281–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ma, C.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, L. Alleviation of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Protects against Cisplatin-Induced Ovarian Damage. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2018, 16, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, W.; Yunqi, Z.; Zimeng, L.; Kangning, X.; Deji, L.; Chen, Q.; Yong, Z.; Fusheng, Q. Large Extracellular Vesicles in Bovine Follicular Fluid Inhibit the Apoptosis of Granulosa Cell and Stimulate the Production of Steroid Hormones. Theriogenology 2023, 195, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoham, Z.; Schachter, M. Estrogen Biosynthesis—Regulation, Action, Remote Effects, and Value of Monitoring in Ovarian Stimulation Cycles. Fertil. Steril. 1996, 65, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batalha, I.M.; Maylem, E.R.S.; Spicer, L.J.; Pena Bello, C.A.; Archilia, E.C.; Schütz, L.F. Effects of Asprosin on Estradiol and Progesterone Secretion and Proliferation of Bovine Granulosa Cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2023, 565, 111890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Qu, J.; Mou, L.; Liu, C. Apigenin Improves Testosterone Synthesis by Regulating Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 177, 117075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, S.; Chen, Y.; Tang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, S.; You, T.; Xu, H. Male Reproductive Toxicity of Polystyrene Microplastics: Study on the Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Signaling Pathway. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2023, 172, 113577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, D.; Wen, X.; Guan, X.; Fang, H.; Liu, Y.; Qin, M.; Wang, H.; Xu, J.; Lv, J.; Zhao, J.; et al. Pubertal Lead Exposure Affects Ovary Development, Folliculogenesis and Steroidogenesis by Activation of IRE1α-JNK Signaling Pathway in Rat. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 257, 114919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wang, L.; Lin, P.; Jiang, T.; Wang, N.; Zhao, F.; Chen, H.; Tang, K.; Zhou, D.; Wang, A.; et al. An Immortalized Steroidogenic Goat Granulosa Cell Line as a Model System to Study the Effect of the Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER)-Stress Response on Steroidogenesis. J. Reprod. Dev. 2017, 63, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanger, D.; Calder, M.D.; Gianetto-Berruti, A.; Lui, E.M.; Watson, A.J.; Feyles, V. Effects of American Ginseng on Preimplantation Development and Pregnancy in Mice. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2016, 44, 981–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Q.-Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Zeng, B.; Wang, F.; Wang, L.-N.; Jiang, Q.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-L. Effect of Ginseng Polysaccharides on the Immunity and Growth of Piglets by Dietary Supplementation during Late Pregnancy and Lactating Sows. Anim. Sci. J. 2017, 88, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Fan, M.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, S.; Li, W. Red Ginseng Improves D-Galactose-Induced Premature Ovarian Failure in Mice Based on Network Pharmacology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Genes | Species | Primer Sequences (5′–3′) | Annealing Temperature, °C | Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCNA | Bovine | F: AAGCCACTCCACTGTCTCCTAC | 61 | NM_001034494.1 |

| R: TCCTTCTTCATCCTCGATCTTGGG | ||||

| CDK2 | Bovine | F: CGCTCACTGGCATTCCTCTTC | 61 | NM_001014934.1 |

| R: GGACCCATCTGCGTTGATAAGC | ||||

| PI3K | Bovine | F: TGGTGACAAGTGGTGGGACAG | 58 | NM_001206047.2 |

| R: AGGTGTAAGTGCCATCTGGTAGC | ||||

| AKT | Bovine | F: TAAGCAGAAGCCTATCACTCCAGAG | 60 | NM_173986.2 |

| R: GCAGAGCACTCCACATACTTGAC | ||||

| CYP11A1 | Bovine | F: GTCAAAGCCTGCCCACCCATC | 61 | NM_176644.2 |

| R: ATGCCAGCTCCCTCTCCAGTG | ||||

| CYP19A1 | Bovine | F: GTCGTCCTGGTCACCCTTCTG | 61 | NM_174305.1 |

| R: GGTCTCTGGTCTCGTCTGGATG | ||||

| STAR | Bovine | F: ATGGTGCTCCGCCCCTTGG | 61 | NM_174189.3 |

| R: TCTGCGAGAGGACCTGGTTGATG | ||||

| RIPK3 | Bovine | F:GTCCACATTTCAGGGAGGCT | 56 | NM_001435166.1 |

| R:GAAGGATCCCAGAGTCTGTCT | ||||

| MLKL | Bovine | F:GGGAGCAGCACTTCTCTGTTA | 62 | XM_059877358.1 |

| R:GGGGCTGCTAAGTCACAATG | ||||

| GRP78 | Bovine | F:CGTGCGTTTGAGAGCTCAGT | 58 | NM_001075148.1 |

| R:TAGGGCTTCGCAGGAAAACC | ||||

| PERK | Bovine | F:CCAGCAAAGAGGAGCCCAGAATG | 60 | NM_174584.3 |

| R:AAGTGGTTGGTCTTGACGGAGAAAC | ||||

| IRE1 | Bovine | F:CCGAAGTTCAGATGGCATTC | 56 | NM_001077828.1 |

| R:TCTGCAAAGGCTGATGACAG | ||||

| ATF6 | Bovine | F:GGATTTGATGCCTTGGGAGACAG | 59 | XM_024989876.2 |

| R:TGAGGAGATGAGATTGAACAACTTGAG | ||||

| β-actin | Bovine | F: TTGATCTTCATTGTGCTGGGTG | 60 | NM_174226.2 |

| R: CTTCCTGGGCATGGAATCCT | ||||

| PCNA | Mouse | F:GAAGTTTTCTGCAAGTGGAGAG | 54 | NM_011045.2 |

| R:CAGGCTCATTCATCTCTATGGT | ||||

| CDK2 | Mouse | F:CCAGGAGTTACTTCTATGCCTGA | 56 | NM_001428414.1 |

| R:TTCATCCAGGGGAGGTACAAC | ||||

| STAR | Mouse | F:CGGGTCTTGGGTCCTGGATTGT | 62 | NM_011485.5 |

| R:GCTGCCCTCGCTCACCTTAAG | ||||

| CYP11A1 | Mouse | F:GCTCAACCTGCCTCCAGACTTC | 61 | NM_011045.2 |

| R:CCTCCTGCCAGCATCTCGGTAA | ||||

| CYP19A1 | Mouse | F:TCGTCGCAGAGTATCCAGAGGT | 60 | NM_001348171.1 |

| R:CGCATGACCAAGTCCACAACAG | ||||

| GRP78 | Mouse | F:CTGGCCGAGACAACACTGACCT | 63 | NM_001163434.1 |

| R:GCGACGACGGTTCTGGTCTCAC | ||||

| β-actin | Mouse | F:GTCTTCCCCTCCATCGTG | 60 | NM_007393.5 |

| R:AGGGTGAGGATGCCTCTCTT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, H.; Fang, Y.; Huang, L.; Yang, X.; Ma, X.; Lyu, Y.; Jing, G.; Ding, H.; Liu, H.; Lyu, W. Ginseng Polysaccharides Protect Against Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Induced Damage via PI3K/Akt Signalling Pathway in Bovine Ovarian Granulosa Cells. Cells 2026, 15, 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020172

Wang H, Fang Y, Huang L, Yang X, Ma X, Lyu Y, Jing G, Ding H, Liu H, Lyu W. Ginseng Polysaccharides Protect Against Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Induced Damage via PI3K/Akt Signalling Pathway in Bovine Ovarian Granulosa Cells. Cells. 2026; 15(2):172. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020172

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Hongjie, Yi Fang, Lei Huang, Xu Yang, Xin Ma, Yang Lyu, Guo Jing, He Ding, Hongyu Liu, and Wenfa Lyu. 2026. "Ginseng Polysaccharides Protect Against Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Induced Damage via PI3K/Akt Signalling Pathway in Bovine Ovarian Granulosa Cells" Cells 15, no. 2: 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020172

APA StyleWang, H., Fang, Y., Huang, L., Yang, X., Ma, X., Lyu, Y., Jing, G., Ding, H., Liu, H., & Lyu, W. (2026). Ginseng Polysaccharides Protect Against Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Induced Damage via PI3K/Akt Signalling Pathway in Bovine Ovarian Granulosa Cells. Cells, 15(2), 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020172