Western Diet Dampens T Regulatory Cell Function to Fuel Hepatic Inflammation in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Mice

2.2. MASLD Diet

2.3. Ex Vivo Analysis of Treg Function

2.4. Treg Depletion

2.5. In Vivo Treg Induction

2.6. Human Tissue

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

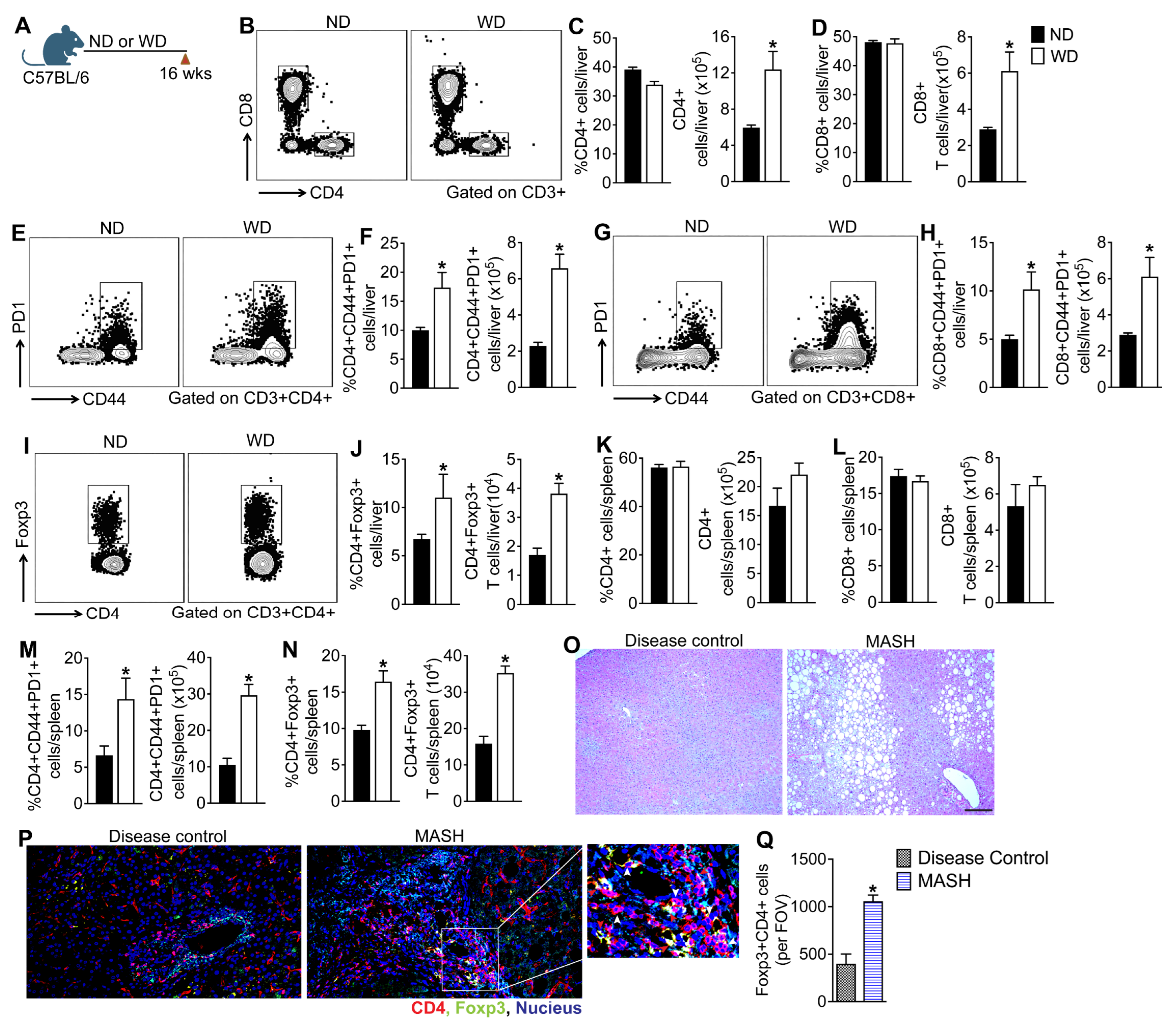

3.1. MASLD Progression in Mice Fed a WD Is Associated with Aberrant Activation of Hepatic and Systemic T Cells

3.2. Myeloid Cells Promote Hepatic Inflammation and Fibrosis in the Absence of Lymphoid Cells

3.3. Depletion of Foxp3+ Regulatory T Cells Reduces Hepatic Steatosis but Exacerbates WD-Induced Hepatic Inflammation

3.4. Depletion of Foxp3+ Regulatory T Cells Exacerbates WD-Induced Hepatic Fibrosis

3.5. Induction of Tregs in WD-Fed Mice Attenuates Hepatic Inflammation and Steatosis

3.6. Treg Expansion Therapy Protects Mice from WD-Induced Liver Fibrosis

3.7. Dietary Glucose and Palmitate Impair Hepatic Treg Function

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anstee, Q.M.; Targher, G.; Day, C.P. Progression of NAFLD to diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease or cirrhosis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 10, 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Stepanova, M.; Ong, J.; Trimble, G.; AlQahtani, S.; Younossi, I.; Ahmed, A.; Racila, A.; Henry, L. Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Is the Most Rapidly Increasing Indication for Liver Transplantation in the United States. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 19, 580–589e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepanova, M.; Kabbara, K.; Mohess, D.; Verma, M.; Roche-Green, A.; AlQahtani, S.; Ong, J.; Burra, P.; Younossi, Z.M. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the most common indication for liver transplantation among the elderly: Data from the United States Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. Hepatol. Commun. 2022, 6, 1506–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rai, R.P.; Liu, Y.; Iyer, S.S.; Liu, S.; Gupta, B.; Desai, C.; Kumar, P.; Smith, T.; Singhi, A.D.; Nusrat, A.; et al. Blocking integrin alpha4beta7-mediated CD4 T cell recruitment to the intestine and liver protects mice from western diet-induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammerich, L.; Tacke, F. Hepatic inflammatory responses in liver fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 20, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woestemeier, A.; Scognamiglio, P.; Zhao, Y.; Wagner, J.; Muscate, F.; Casar, C.; Siracusa, F.; Cortesi, F.; Agalioti, T.; Muller, S.; et al. Multicytokine-producing CD4+ T cells characterize the livers of patients with NASH. JCI Insight 2023, 8, e153831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chapman, N.M.; Boothby, M.R.; Chi, H. Metabolic coordination of T cell quiescence and activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakaguchi, S.; Mikami, N.; Wing, J.B.; Tanaka, A.; Ichiyama, K.; Ohkura, N. Regulatory T Cells and Human Disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 38, 541–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, S. T Cells in Fibrosis and Fibrotic Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Germain, R.N. T-cell development and the CD4-CD8 lineage decision. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002, 2, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Josefowicz, S.Z.; Lu, L.F.; Rudensky, A.Y. Regulatory T cells: Mechanisms of differentiation and function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 30, 531–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ghazarian, M.; Revelo, X.S.; Nohr, M.K.; Luck, H.; Zeng, K.; Lei, H.; Tsai, S.; Schroer, S.A.; Park, Y.J.; Chng, M.H.Y.; et al. Type I Interferon Responses Drive Intrahepatic T cells to Promote Metabolic Syndrome. Sci. Immunol. 2017, 2, eaai7616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Seike, T.; Mizukoshi, E.; Yamada, K.; Okada, H.; Kitahara, M.; Yamashita, T.; Arai, K.; Terashima, T.; Iida, N.; Fushimi, K.; et al. Fatty acid-driven modifications in T-cell profiles in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 55, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soderberg, C.; Marmur, J.; Eckes, K.; Glaumann, H.; Sallberg, M.; Frelin, L.; Rosenberg, P.; Stal, P.; Hultcrantz, R. Microvesicular fat, inter cellular adhesion molecule-1 and regulatory T-lymphocytes are of importance for the inflammatory process in livers with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. APMIS 2011, 119, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rau, M.; Schilling, A.K.; Meertens, J.; Hering, I.; Weiss, J.; Jurowich, C.; Kudlich, T.; Hermanns, H.M.; Bantel, H.; Beyersdorf, N.; et al. Progression from Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver to Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Is Marked by a Higher Frequency of Th17 Cells in the Liver and an Increased Th17/Resting Regulatory T Cell Ratio in Peripheral Blood and in the Liver. J. Immunol. 2016, 196, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rau, M.; Rehman, A.; Dittrich, M.; Groen, A.K.; Hermanns, H.M.; Seyfried, F.; Beyersdorf, N.; Dandekar, T.; Rosenstiel, P.; Geier, A. Fecal SCFAs and SCFA-producing bacteria in gut microbiome of human NAFLD as a putative link to systemic T-cell activation and advanced disease. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2018, 6, 1496–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, H.; Tsung, A.; Mishra, L.; Huang, H. Regulatory T cell: A double-edged sword from metabolic-dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis to hepatocellular carcinoma. EBioMedicine 2024, 101, 105031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barrow, F.; Khan, S.; Fredrickson, G.; Wang, H.; Dietsche, K.; Parthiban, P.; Robert, S.; Kaiser, T.; Winer, S.; Herman, A.; et al. Microbiota-Driven Activation of Intrahepatic B Cells Aggravates NASH Through Innate and Adaptive Signaling. Hepatology 2021, 74, 704–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Her, Z.; Tan, J.H.L.; Lim, Y.S.; Tan, S.Y.; Chan, X.Y.; Tan, W.W.S.; Liu, M.; Yong, K.S.M.; Lai, F.; Ceccarello, E.; et al. CD4(+) T Cells Mediate the Development of Liver Fibrosis in High Fat Diet-Induced NAFLD in Humanized Mice. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 580968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dywicki, J.; Buitrago-Molina, L.E.; Noyan, F.; Davalos-Misslitz, A.C.; Hupa-Breier, K.L.; Lieber, M.; Hapke, M.; Schlue, J.; Falk, C.S.; Raha, S.; et al. The Detrimental Role of Regulatory T Cells in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Hepatol. Commun. 2022, 6, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Savage, T.M.; Fortson, K.T.; de Los Santos-Alexis, K.; Oliveras-Alsina, A.; Rouanne, M.; Rae, S.S.; Gamarra, J.R.; Shayya, H.; Kornberg, A.; Cavero, R.; et al. Amphiregulin from regulatory T cells promotes liver fibrosis and insulin resistance in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Immunity 2024, 57, 303–318.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Brown, Z.J.; Xia, Y.; Huang, Z.; Shen, C.; Hu, Z.; Beane, J.; Ansa-Addo, E.A.; et al. Regulatory T-cell and neutrophil extracellular trap interaction contributes to carcinogenesis in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2021, 75, 1271–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Herck, M.A.; Vonghia, L.; Kwanten, W.J.; Vanwolleghem, T.; Ebo, D.G.; Michielsen, P.P.; De Man, J.G.; Gama, L.; De Winter, B.Y.; Francque, S.M. Adoptive Cell Transfer of Regulatory T Cells Exacerbates Hepatic Steatosis in High-Fat High-Fructose Diet-Fed Mice. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Roh, Y.S.; Kim, J.W.; Park, S.; Shon, C.; Kim, S.; Eo, S.K.; Kwon, J.K.; Lim, C.W.; Kim, B. Toll-Like Receptor-7 Signaling Promotes Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis by Inhibiting Regulatory T Cells in Mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2018, 188, 2574–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.M.; Rasmussen, J.P.; Rudensky, A.Y. Regulatory T cells prevent catastrophic autoimmunity throughout the lifespan of mice. Nat. Immunol. 2007, 8, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, K.; Desai, C.; Iyer, S.S.; Thorn, N.E.; Kumar, P.; Liu, Y.; Smith, T.; Neish, A.S.; Li, H.; Tan, S.; et al. Loss of Junctional Adhesion Molecule A Promotes Severe Steatohepatitis in Mice on a Diet High in Saturated Fat, Fructose, and Cholesterol. Gastroenterology 2016, 151, 733–746.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penaloza-MacMaster, P.; Kamphorst, A.O.; Wieland, A.; Araki, K.; Iyer, S.S.; West, E.E.; O’Mara, L.; Yang, S.; Konieczny, B.T.; Sharpe, A.H.; et al. Interplay between regulatory T cells and PD-1 in modulating T cell exhaustion and viral control during chronic LCMV infection. J. Exp. Med. 2014, 211, 1905–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Boyman, O.; Kovar, M.; Rubinstein, M.P.; Surh, C.D.; Sprent, J. Selective stimulation of T cell subsets with antibody-cytokine immune complexes. Science 2006, 311, 1924–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Kesarwala, A.H.; Eggert, T.; Medina-Echeverz, J.; Kleiner, D.E.; Jin, P.; Stroncek, D.F.; Terabe, M.; Kapoor, V.; ElGindi, M.; et al. NAFLD causes selective CD4(+) T lymphocyte loss and promotes hepatocarcinogenesis. Nature 2016, 531, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bennett, C.L.; Clausen, B.E. DC ablation in mice: Promises, pitfalls, and challenges. Trends Immunol. 2007, 28, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorburn, J.; Frankel, A.E.; Thorburn, A. Apoptosis by leukemia cell-targeted diphtheria toxin occurs via receptor-independent activation of Fas-associated death domain protein. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003, 9, 861–865. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miyake, Y.; Kaise, H.; Isono, K.; Koseki, H.; Kohno, K.; Tanaka, M. Protective role of macrophages in noninflammatory lung injury caused by selective ablation of alveolar epithelial type II Cells. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 5001–5009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamada, T.; Togashi, Y.; Tay, C.; Ha, D.; Sasaki, A.; Nakamura, Y.; Sato, E.; Fukuoka, S.; Tada, Y.; Tanaka, A.; et al. PD-1(+) regulatory T cells amplified by PD-1 blockade promote hyperprogression of cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 9999–10008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gerriets, V.A.; Kishton, R.J.; Johnson, M.O.; Cohen, S.; Siska, P.J.; Nichols, A.G.; Warmoes, M.O.; de Cubas, A.A.; MacIver, N.J.; Locasale, J.W.; et al. Foxp3 and Toll-like receptor signaling balance T(reg) cell anabolic metabolism for suppression. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 1459–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wei, J.; Long, L.; Yang, K.; Guy, C.; Shrestha, S.; Chen, Z.; Wu, C.; Vogel, P.; Neale, G.; Green, D.R.; et al. Autophagy enforces functional integrity of regulatory T cells by coupling environmental cues and metabolic homeostasis. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bhattacharjee, J.; Kumar, J.M.; Arindkar, S.; Das, B.; Pramod, U.; Juyal, R.C.; Majumdar, S.S.; Nagarajan, P. Role of immunodeficient animal models in the development of fructose induced NAFLD. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2014, 25, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, M.J.; Adili, A.; Piotrowitz, K.; Abdullah, Z.; Boege, Y.; Stemmer, K.; Ringelhan, M.; Simonavicius, N.; Egger, M.; Wohlleber, D.; et al. Metabolic activation of intrahepatic CD8+ T cells and NKT cells causes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and liver cancer via cross-talk with hepatocytes. Cancer Cell 2014, 26, 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snook, J.P.; Kim, C.; Williams, M.A. TCR signal strength controls the differentiation of CD4(+) effector and memory T cells. Sci. Immunol. 2018, 3, eaas9103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shi, H.; Chi, H. Metabolic Control of Treg Cell Stability, Plasticity, and Tissue-Specific Heterogeneity. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Issa, F.; Wood, K.J. Translating tolerogenic therapies to the clinic-where do we stand? Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Komatsu, N.; Mariotti-Ferrandiz, M.E.; Wang, Y.; Malissen, B.; Waldmann, H.; Hori, S. Heterogeneity of natural Foxp3+ T cells: A committed regulatory T-cell lineage and an uncommitted minor population retaining plasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 1903–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tsuji, M.; Komatsu, N.; Kawamoto, S.; Suzuki, K.; Kanagawa, O.; Honjo, T.; Hori, S.; Fagarasan, S. Preferential generation of follicular B helper T cells from Foxp3+ T cells in gut Peyer’s patches. Science 2009, 323, 1488–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, J.H.; Zelenay, S.; Bergman, M.L.; Martins, A.C.; Demengeot, J. Natural Treg cells spontaneously differentiate into pathogenic helper cells in lymphopenic conditions. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009, 39, 948–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, V.; Lakhan, R.; Iyyathurai, J.; Bromberg, J.S. Mechanisms of exTreg induction. Eur. J. Immunol. 2021, 51, 1956–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, K.J.; Qian, Q.F.; Zhou, J.R.; Sun, D.L.; Duan, Y.F.; Zhu, X.; Sartorius, K.; Lu, Y.J. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) in liver fibrosis. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Taylor, A.E.; Carey, A.N.; Kudira, R.; Lages, C.S.; Shi, T.; Lam, S.; Karns, R.; Simmons, J.; Shanmukhappa, K.; Almanan, M.; et al. Interleukin 2 Promotes Hepatic Regulatory T Cell Responses and Protects From Biliary Fibrosis in Murine Sclerosing Cholangitis. Hepatology 2018, 68, 1905–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Michalek, R.D.; Gerriets, V.A.; Jacobs, S.R.; Macintyre, A.N.; MacIver, N.J.; Mason, E.F.; Sullivan, S.A.; Nichols, A.G.; Rathmell, J.C. Cutting edge: Distinct glycolytic and lipid oxidative metabolic programs are essential for effector and regulatory CD4+ T cell subsets. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 3299–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shi, L.Z.; Wang, R.; Huang, G.; Vogel, P.; Neale, G.; Green, D.R.; Chi, H. HIF1alpha-dependent glycolytic pathway orchestrates a metabolic checkpoint for the differentiation of TH17 and Treg cells. J. Exp. Med. 2011, 208, 1367–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Eleftheriadis, T.; Pissas, G.; Karioti, A.; Antoniadi, G.; Antoniadis, N.; Liakopoulos, V.; Stefanidis, I. Dichloroacetate at therapeutic concentration alters glucose metabolism and induces regulatory T-cell differentiation in alloreactive human lymphocytes. J. Basic. Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2013, 24, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, N.; Blagih, J.; Zani, F.; Rees, A.; Hill, D.G.; Jenkins, B.J.; Bull, C.J.; Moreira, D.; Bantan, A.I.M.; Cronin, J.G.; et al. Fructose reprogrammes glutamine-dependent oxidative metabolism to support LPS-induced inflammation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Weinberg, S.E.; Singer, B.D.; Steinert, E.M.; Martinez, C.A.; Mehta, M.M.; Martinez-Reyes, I.; Gao, P.; Helmin, K.A.; Abdala-Valencia, H.; Sena, L.A.; et al. Mitochondrial complex III is essential for suppressive function of regulatory T cells. Nature 2019, 565, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kumagai, S.; Togashi, Y.; Sakai, C.; Kawazoe, A.; Kawazu, M.; Ueno, T.; Sato, E.; Kuwata, T.; Kinoshita, T.; Yamamoto, M.; et al. An Oncogenic Alteration Creates a Microenvironment that Promotes Tumor Progression by Conferring a Metabolic Advantage to Regulatory T Cells. Immunity 2020, 53, 187–203 e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chaudhary, S.; Rai, R.; Pal, P.B.; Tedesco, D.; Rossmiller, D.; Gupta, B.; Singhi, A.D.; Monga, S.P.; Grakoui, A.; Iyer, S.S.; et al. Western Diet Dampens T Regulatory Cell Function to Fuel Hepatic Inflammation in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Cells 2026, 15, 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020165

Chaudhary S, Rai R, Pal PB, Tedesco D, Rossmiller D, Gupta B, Singhi AD, Monga SP, Grakoui A, Iyer SS, et al. Western Diet Dampens T Regulatory Cell Function to Fuel Hepatic Inflammation in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Cells. 2026; 15(2):165. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020165

Chicago/Turabian StyleChaudhary, Sudrishti, Ravi Rai, Pabitra B. Pal, Dana Tedesco, Daniel Rossmiller, Biki Gupta, Aatur D. Singhi, Satdarshan P. Monga, Arash Grakoui, Smita S. Iyer, and et al. 2026. "Western Diet Dampens T Regulatory Cell Function to Fuel Hepatic Inflammation in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease" Cells 15, no. 2: 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020165

APA StyleChaudhary, S., Rai, R., Pal, P. B., Tedesco, D., Rossmiller, D., Gupta, B., Singhi, A. D., Monga, S. P., Grakoui, A., Iyer, S. S., & Raeman, R. (2026). Western Diet Dampens T Regulatory Cell Function to Fuel Hepatic Inflammation in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Cells, 15(2), 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020165