Retinal Degeneration in Alzheimer’s Disease 5xFAD Mice Fed DHA-Enriched Diets

Highlights

- The adequate intake of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n − 3) is important for preventing cognitive decline and assuring brain optimal function, especially in early Alzheimer’s disease (AD) stages.

- The pivotal role of DHA for protecting retinal integrity in AD remains elusive.

- The neuroprotective effects of DHA supplementation in 5xFAD mice were found in the retina, from both fish oil and DHASCO commercial oil, concerning the retinal layer thickness, TAU protein aggregates, and retinal ganglion cell layer density, respectively.

- These retinal alterations promoted by dietary DHA reinforce the retina as a valuable site for detecting and monitoring AD.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Mice, Experimental Design, and Diets

2.3. Fatty Acid Composition of the Experimental Diets

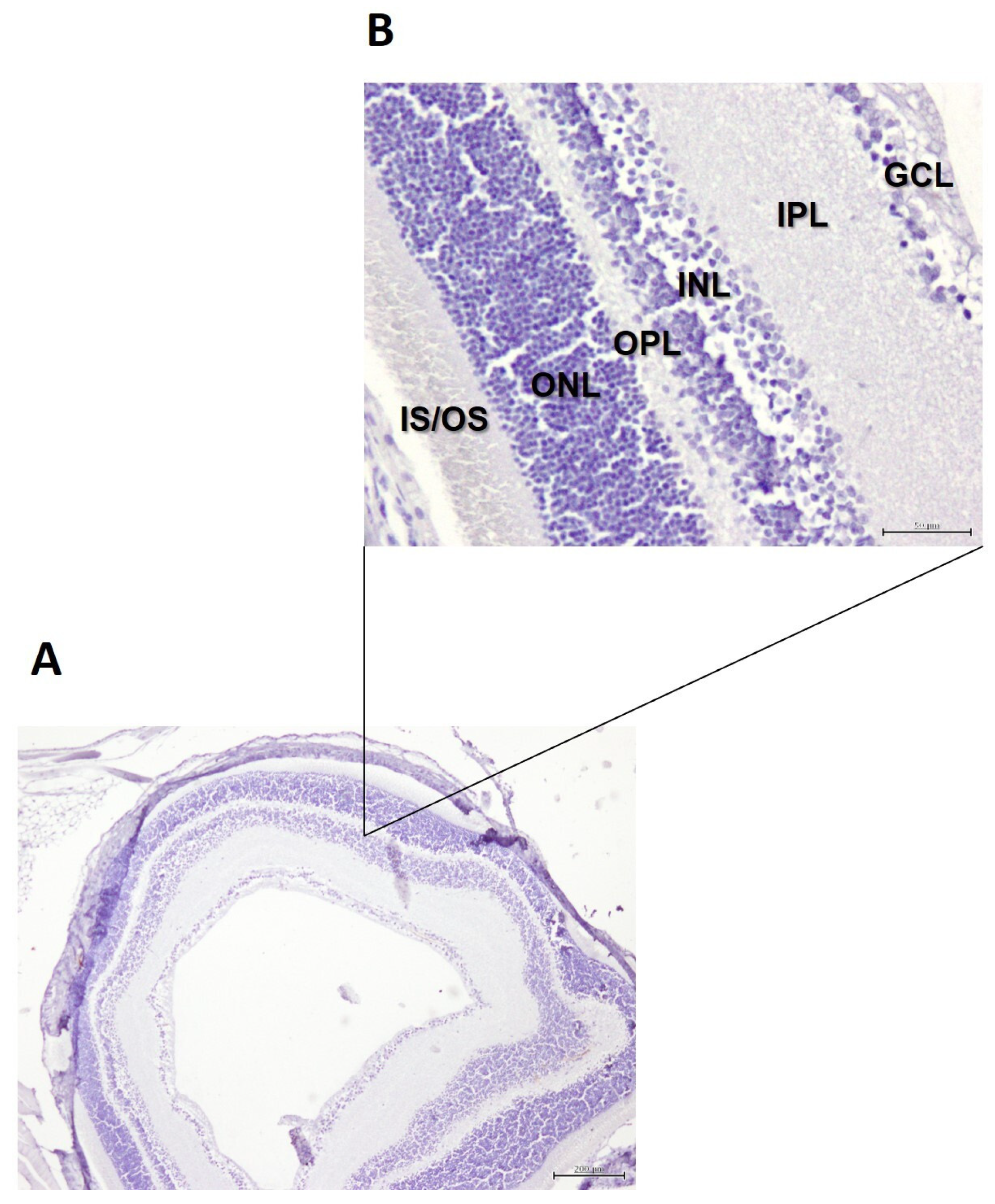

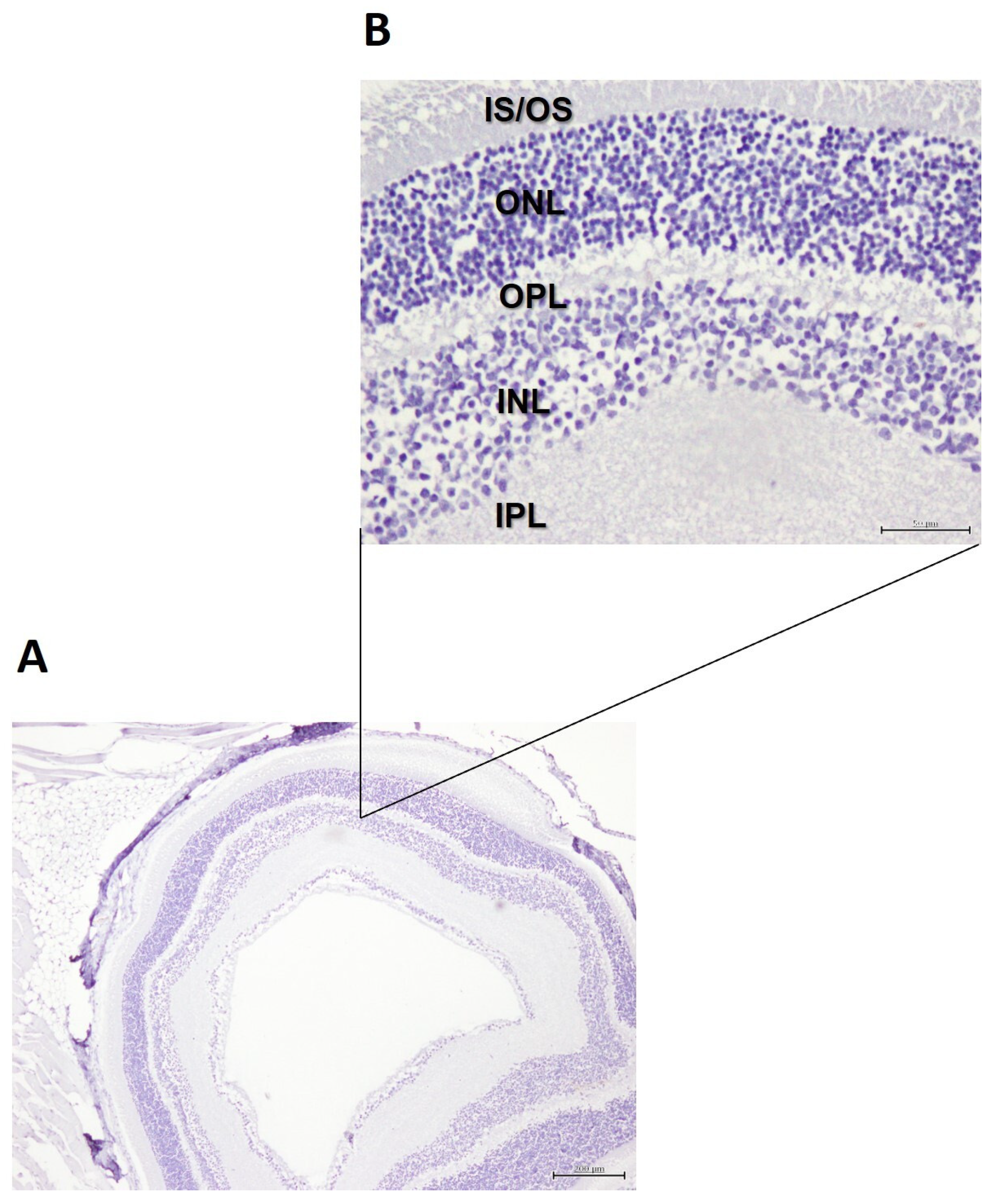

2.4. Histology of the Retina

2.5. Quantification of Cell Density in the GCL of the Retina

2.6. Retinal Immunohistochemistry

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

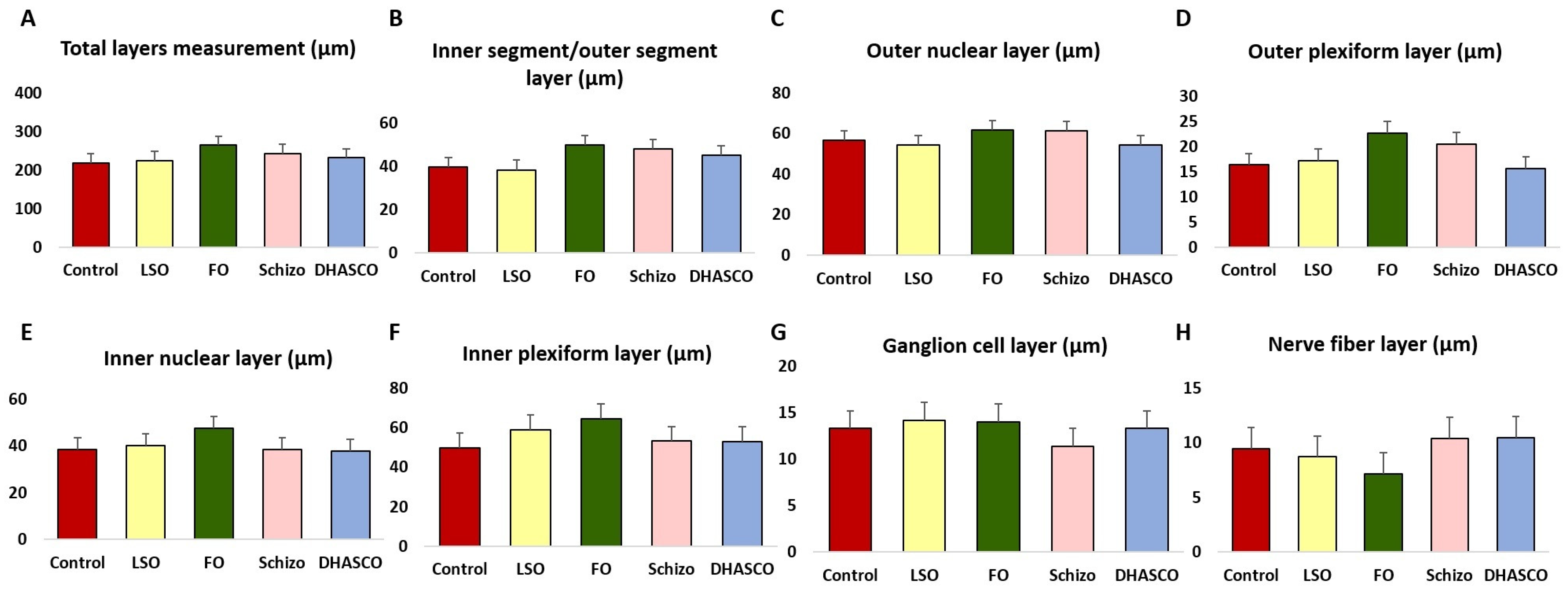

3.1. Retinal Layer Thickness in the Retina of 5xFAD Mice Fed DHA-Enriched Diets

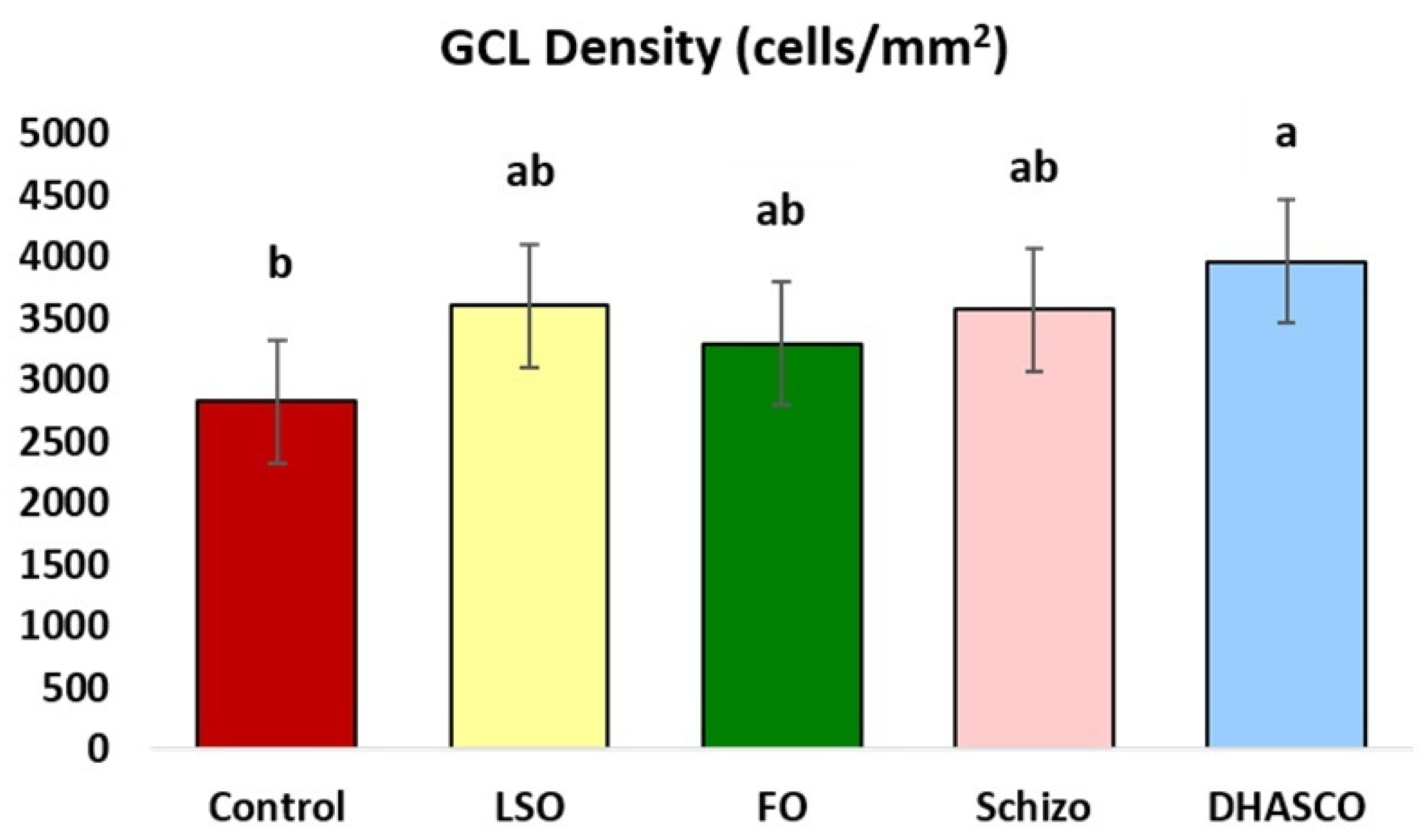

3.2. Ganglion Cell Layer (GCL) Density in the Retina of 5xFAD Mice Fed DHA-Enriched Diets

3.3. Immunohistochemical Staining for β-Amyloid Plaques in the Retina of 5xFAD Mice Fed DHA-Enriched Diets

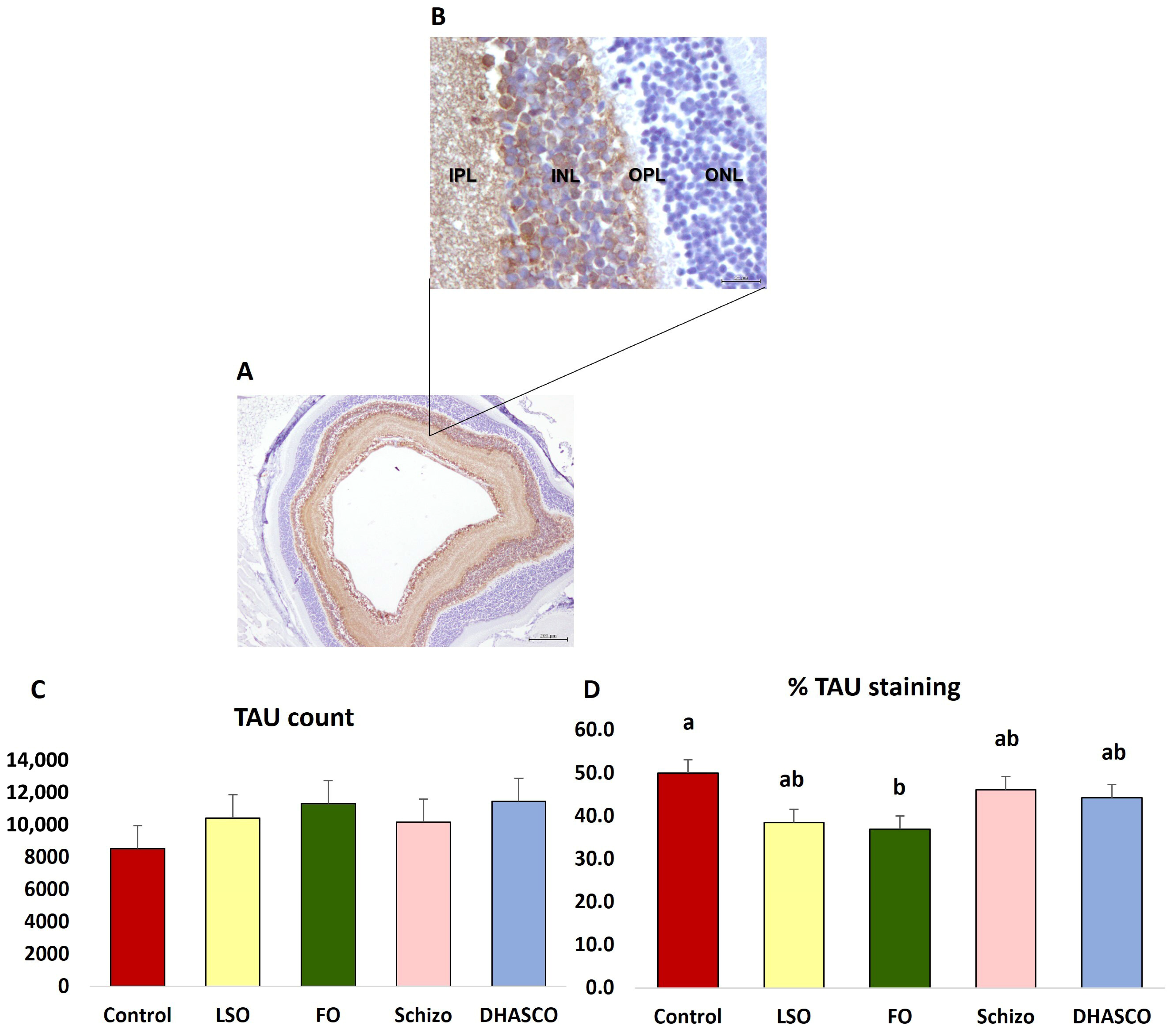

3.4. Immunohistochemical Staining for TAU in the Retina of 5xFAD Mice Fed DHA-Enriched Diets

3.5. Immunohistochemical Staining for IBA1 in the Retina of 5xFAD Mice Fed DHA-Enriched Diets

3.6. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) Using Retinal Layer Thickness, GCL Density, and TAU Immunohistochemistry in the Retina of 5xFAD Mice Fed DHA-Enriched Diets

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bambo, M.P.; Garcia-Martin, E.; Pinilla, J.; Herrero, R.; Satue, M.; Otin, S.; Fuertes, I.; Marques, M.L.; Pablo, L.E. Detection of retinal nerve fiber layer degeneration in patients with Alzheimer’s disease using optical coherence tomography: Searching new biomarkers. Acta Ophthalmol. 2014, 92, e581–e582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiquita, S.; Rodrigues-Neves, A.C.; Baptista, F.I.; Carecho, R.; Moreira, P.I.; Castelo-Branco, M.; Ambrósio, A.F. The retina as a window or mirror of the brain changes detected in Alzheimer’s disease: Critical aspects to unravel. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 5416–5435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masland, R.H. The neuronal organization of the retina. Neuron 2012, 76, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlina, W. Histology. A Text and Atlas: With Correlated Cell and Molecular Biology, 8th ed.; Wolters Kluver Health: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Swinkels, D.; Baes, M. The essential role of docosahexaenoic acid and its derivatives for retinal integrity. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 247, 108440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Thomas, C.J.; Radcliffe, J.; Itsiopoulos, C. Omega-3 fatty acids in early prevention of inflammatory neurodegenerative disease: A focus on Alzheimer’s disease. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 172801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras-Sandoval, D.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Pérez-Rojas, J.M. Role of docosahexaenoic acid in the modulation of glial cells in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroinflammation 2016, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Létondor, A.; Buaud, B.; Vaysse, C.; Richard, E.; Layé, S.; Pallet, V.; Alfos, S. EPA/DHA and vitamin A supplementation improves spatial memory and alleviates the age-related decrease in hippocampal RXRγ and kinase expression in rats. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2016, 8, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pádua, M.S.; Guil-Guerrero, J.L.; Lopes, P.A. Behaviour hallmarks in Alzheimer’s disease 5xFAD mouse model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pádua, M.S.; Guil-Guerrero, J.L.; Prates, J.A.M.; Lopes, P.A. Insights on the use of transgenic mice models in Alzheimer’s disease research. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, H.; Cole, S.L.; Logan, S.; Maus, E.; Shao, P.; Craft, J.; Guillozet-Bongaarts, A.; Ohno, M.; Disterhoft, J.; Eldik, L.V.; et al. Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations: Potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 10129–10140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowsky, J.L.; Zheng, H. Practical considerations for choosing a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2017, 12, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayabe, T.; Ano, Y. Alzheimer model 5xfad mice and applications to dementia: Transgenic mouse models, a focus on neuroinflammation, microglia, and food-derived components. In Genetics, Neurology, Behavior, and Diet in Dementia; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 833–847. [Google Scholar]

- Ismeurt, C.; Giannoni, P.; Claeysen, S. The 5XFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. In Diagnosis and Management in Dementia; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 207–221. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Jiang, K.; McIlmoyle, B.; To, E.; Qinyuan, A.X.; Hirsch-Reinshagen, V.; Mackenzie, I.R.; Hsiung, G.-Y.R.; Eadie, B.D.; Sarunic, M.V.; et al. Amyloid Beta immunoreactivity in the retinal ganglion cell layer of the Alzheimer’s eye. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-de-Eguileta, A.; Cerveró, A.; Ruiz de Sabando, A.; Sánchez-Juan, P.; Casado, A. Ganglion cell layer thinning in Alzheimer’s disease. Medicina 2020, 56, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanks, J.C.; Hinton, D.R.; Sadun, A.A.; Miller, C.A. Retinal ganglion cell degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 1989, 501, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Morgia, C.; Ross-Cisneros, F.N.; Sadun, A.A.; Carelli, V. Retinal ganglion cells and circadian rhythms in Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and beyond. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevan, R.J.; Hughes, T.R.; Williams, P.A.; Good, M.A.; Morgan, B.P.; Morgan, J.E. Retinal ganglion cell degeneration correlates with hippocampal spine loss in experimental Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. Comm. 2020, 8, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zutphen, L.F.M.; Baumans, V.; Beynen, A.C. Principles of Laboratory Animal Science: A Contribution to the Humane Use and Care of Animals and to the Quality of Experimental Results, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; p. 416. [Google Scholar]

- Folch, J.; Lees, M.; Stanley, G.H. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1957, 226, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandarra, N.M.; Batista, I.; Nunes, M.L.; Empis, J.M.; Christie, W.W. Seasonal changes in lipid composition of sardine (Sardina pilchardus). J. Food Sci. 1997, 62, 40–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A.; Pike, C. Staining and quantification of β-amyloid pathology in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. In Aging: Methods and Protocols; Curran, S., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2020; Chapter 19; pp. 211–221. [Google Scholar]

- de Mello-Sampayo, C.; Pádua, M.S.; Silva, M.R.; Lourenço, M.; Pinto, R.M.A.; Carvalho, S.; Correia, J.; Martins, C.F.; Gomes, R.; Gomes-Bispo, A.; et al. Neuronal count, brain injury, and sustained cognitive function in 5×FAD Alzheimer’s disease mice fed DHA-enriched diets. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAS/STAT. SAS User’s Guide, Version 9.1; SAS Institute: Cary, NC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ashok, A.; Singh, N.; Chaudhary, S.; Bellamkonda, V.; Kritikos, A.E.; Wise, A.S.; Rana, N.; McDonald, D.; Ayyagari, R. Retinal degeneration and Alzheimer’s disease: An evolving link. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhong, L.; Han, X.; Xiong, G.; Xu, D.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, H.; Chiu, K.; Xu, Y. Brain and retinal abnormalities in the 5xFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease at early stages. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 681831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, J.; Kwapong, W.R.; Shen, T.; Fu, H.; Xu, Y.; Lu, Q.; Liu, S.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Early detection of dementia through retinal imaging and trustworthy AI. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.-J.; Huang, L.-F.; Deng, J.-L.; Wang, Y.-M.; Guo, C.; Peng, X.-N.; Liu, Z.; Gao, J.-M. Cognitive enhancement and neuroprotective effects of OABL, a sesquiterpene lactone in 5xFAD Alzheimer’s disease mice model. Redox Biol. 2022, 50, 102229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eimer, W.A.; Vassar, R. Neuron loss in the 5XFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease correlates with intraneuronal Aβ42 accumulation and caspase-3 activation. Mol. Neurodegener. 2013, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, S.D.; Baranger, K.; Gauthier, C.; Jacquet, M.; Bernard, A.; Escoffier, G.; Marchetti, E.; Khrestchatisky, M.; Rivera, S.; Roman, F.S. Evidence for early cognitive impairment related to frontal cortex in the 5XFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2013, 33, 781–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boza-Serrano, A.; Yang, Y.; Paulus, A.; Deierborg, T. Innate immune alterations are elicited in microglial cells before plaque deposition in the Alzheimer’s disease mouse model 5xFAD. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forner, S.; Kawauchi, S.; Balderrama-Gutierrez, G.; Kramár, E.A.; Matheos, D.P.; Phan, J.; Javonillo, D.I.; Tran, K.M.; Hingco, E.; Cunha, C.; et al. Systematic phenotyping and characterization of the 5xFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.Y.; Liu, P.-K.; Wen, Y.-T.; Quinn, P.M.J.; Levi, S.R.; Wang, N.-K.; Tsai, R.-K. Role of oxidative stress in ocular diseases associated with retinal ganglion cells degeneration. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, A.; Coelho, I.; Motta, C.; Cardoso, C.; Gomes-Bispo, A.; Afonso, C.; Prates, J.A.M.; Bandarra, N.M.; Silva, J.A.L.; Castanheira, I. Seasonal variation of chub mackerel (Scomber colias) selenium and vitamin B12 content and its potential role in human health. J. Food Comp. Analys. 2022, 109, 104502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penniston, K.L.; Tanumihardjo, S.A. The acute and chronic toxic effects of vitamin A. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 83, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carazo, A.; Macáková, K.; Matoušová, K.; Krčmová, L.K.; Protti, M.; Mladěnka, P. Vitamin A update: Forms, sources, kinetics, detection, function, deficiency, therapeutic use and toxicity. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrón, E.; Mares, J.; Clemons, T.E.; Swaroop, A.; Chew, E.Y.; Keenan, T.D.L. AREDS and AREDS2 Research Groups. Dietary nutrient intake and progression to late age-related macular degeneration in the age-related eye disease studies 1 and 2. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, C.Y.; Mok, V.; Foster, P.J.; Trucco, E.; Chen, C.; Wong, T.Y. Retinal imaging in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2021, 92, 983–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banghart, M.; Lee, K.; Bahrainian, M.; Staggers, K.; Amos, C.; Liu, Y.; Domalpally, A.; Frankfort, B.J.; Sohn, E.H.; Abramoff, M.; et al. Total retinal thickness: A neglected factor in the evaluation of inner retinal thickness. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2022, 7, e001061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.N.; Marsh, J.W.; Tsipursky, M.S.; Boppart, S.A. Ratiometric analysis of in vivo optical coherence tomography retinal layer thicknesses for detection of changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Transl. Biophotonics 2023, 5, e202300003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, N.J.; Koronyo, Y.; Black, K.L.; Koronyo-Hamaoui, M. Ocular indicators of Alzheimer’s: Exploring disease in the retina. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 132, 767–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koronyo, Y.; Biggs, D.; Barron, E.; Boyer, D.S.; Pearlman, J.A.; Au, W.J.; Kile, S.J.; Blanco, A.; Fuchs, D.T.; Ashfaq, A.; et al. Retinal amyloid pathology and proof-of-concept imaging trial in Alzheimer’s disease. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e93621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, N.; Shi, H.; Oviatt, M.; Doustar, J.; Rentsendorj, A.; Fuchs, D.T.; Sheyn, J.; Black, K.L.; Koronyo, Y.; Koronyo-Hamaoui, M. Alzheimer’s retinopathy: Seeing disease in the eyes. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.A.; Boerkoel, P.; Hirsch-Reinshagen, V.; Mackenzie, I.R.; Hsiung, G.R.; Charm, G.; To, E.F.; Liu, A.Q.; Schwab, K.; Jiang, K.; et al. Müller cell degeneration and microglial dysfunction in the Alzheimer’s retina. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2022, 10, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaire, B.P.; Koronyo, Y.; Fuchs, D.T.; Shi, H.; Rentsendorj, A.; Danziger, R.; Vit, J.P.; Mirzaei, N.; Doustar, J.; Sheyn, J.; et al. Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology in the Retina. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2024, 101, 101273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palko, S.I.; Benoit, M.R.; Yao, A.Y.; Mohan, R.; Yan, R. ER-stress response in retinal Müller glia occurs significantly earlier than amyloid pathology in the Alzheimer’s mouse brain and retina. Glia 2024, 72, 1067–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, C.Y.; Troncoso, J.C.; Knox, D.; Stark, W.; Eberhart, C.G. Beta-amyloid, phospho-tau and alpha-synuclein deposits similar to those in the brain are not identified in the eyes of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease patients. Brain Pathol. 2014, 24, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, E.A.; McGuone, D.; Frosch, M.P.; Hyman, B.T.; Laver, N.; Stemmer-Rachamimov, A. Absence of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes in eyes of subjects with Alzheimer disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2017, 76, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schön, C.; Hoffmann, N.A.; Ochs, S.M.; Burgold, S.; Filser, S.; Steinbach, S.; Seeliger, M.W.; Arzberger, T.; Goedert, M.; Kretzschmar, H.A.; et al. Long-term in vivo imaging of fibrillar tau in the retina of P301S transgenic mice. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e53547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Haan, J.; Verbraak, F.D.; Visser, P.J.; Bouwman, F.H. Retinal thickness in Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2017, 6, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, A.; Pediconi, N.; Oieni, F.; Pizzarelli, R.; Rosito, M.; Giubettini, M.; Santini, T.; Limatola, C.; Ruocco, G.; Ragozzino, D.; et al. Neuroinflammatory processes, A1 astrocyte activation and protein aggregation in the retina of Alzheimer’s disease patients, possible biomarkers for early diagnosis. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Koronyo, Y.; Mirzaei, N.; Yang, C.; Fuchs, D.T.; Black, K.L.; Koronyo-Hamaoui, M.; Gao, L. Label-free hyperspectral imaging and deep-learning prediction of retinal amyloid β-protein and phosphorylated tau. PNAS Nexus 2022, 1, pgac164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart de Ruyter, F.J.; Morrema, T.H.J.; den Haan, J.; Netherlands, B.B.; Twisk, J.W.R.; de Boer, J.F.; Scheltens, P.; Boon, B.D.C.; Thal, D.R.; Rozemuller, A.J.; et al. Phosphorylated tau in the retina correlates with tau pathology in the brain in Alzheimer’s disease and primary tauopathies. Acta Neuropathol. 2023, 145, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuñez-Diaz, C.; Andersson, E.; Schultz, N.; Pocevičiūtė, D.; Hansson, O.; Netherlands, B.B.; Nilsson, K.P.R.; Wennström, M. The fluorescent ligand bTVBT2 reveals increased p-tau uptake by retinal microglia in Alzheimer’s disease patients and AppNL-F/NL-F mice. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2024, 16, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Mirzaei, N.; Koronyo, Y.; Davis, M.R.; Robinson, E.; Braun, G.M.; Jallow, O.; Rentsendorj, A.; Ramanujan, V.K.; Fert-Bober, J.; et al. Identification of retinal tau oligomers, citrullinated tau, and other tau isoforms in early and advanced AD and relations to disease status. Acta Neuropathol. 2024, 148, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkiewicz, G.; Ronisz, A.; Van Ginderdeuren, R.; Lemmens, S.; Bouwman, F.H.; Hoozemans, J.J.M.; Morrema, T.H.J.; Rozemuller, A.J.; Hart de Ruyter, F.J.; De Groef, L.; et al. Primary retinal tauopathy: A tauopathy with a distinct molecular pattern. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uras, I.; Karayel-Basar, M.; Sahin, B.; Baykal, A.T. Detection of early proteomic alterations in 5xFAD Alzheimer’s disease neonatal mouse model via MALDI-MSI. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023, 19, 4572–4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oblak, A.L.; Lin, P.B.; Kotredes, K.P.; Pandey, R.S.; Garceau, D.; Williams, H.M.; Uyar, A.; O’Rourke, R.; O’Rourke, S.; Ingraham, C.; et al. Comprehensive evaluation of the 5XFAD mouse model for preclinical testing applications: A MODEL-AD study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 713726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.; Park, S.; Lee, H.; Kim, Y. Thioflavin-positive tau aggregates complicating quantification of amyloid plaques in the brain of 5XFAD transgenic mouse model. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnetti, L.; Chipi, E.; Salvadori, N.; D’Andrea, K.; Eusebi, P. Prevalence and risk of progression of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease stages: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2019, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koronyo, Y.; Rentsendorj, A.; Mirzaei, N.; Regis, G.C.; Sheyn, J.; Shi, H.; Barron, E.; Cook-Wiens, G.; Rodriguez, A.R.; Medeiros, R.; et al. Retinal pathological features and proteome signatures of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2023, 145, 409–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanks, J.C.; Schmidt, S.Y.; Torigoe, Y.; Porrello, K.V.; Hinton, D.R.; Blanks, R.H. Retinal pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. II. Regional neuron loss and glial changes in GCL. Neurobiol. Aging 1996, 17, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, F.; Fumi, D.; Bassis, L.; Pippo, M.D.; Abdolrahimzadeh, S. The role of the ganglion cell layer as an OCT biomarker in neurodegenerative diseases. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2025, 24, 26039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dräger, U.C.; Olsen, J.F. Ganglion cell distribution in the retina of the mouse. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1981, 20, 285–293. [Google Scholar]

- Muthuswamy, A.; Chen, H.; Hu, Y.; Turner, O.C.; Aina, O.H. Mammalian retinal cell quantification. Toxicol. Pathol. 2020, 49, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claes, M.; Moons, L. Retinal ganglion cells: Global number, density and vulnerability to Glaucomatous injury in common laboratory mice. Cells 2022, 11, 2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marziani, E.; Pomati, S.; Ramolfo, P.; Cigada, M.; Giani, A.; Mariani, C.; Staurenghi, G. Evaluation of retinal nerve fiber layer and ganglion cell layer thickness in Alzheimer’s disease using Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, 5953–5958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-de-Eguileta, A.; Lage, C.; López-García, S.; Pozueta, A.; García-Martínez, M.; Kazimierczak, M.; Bravo, M.; de Arcocha-Torres, M.; Banzo, I.; Jimenez-Bonilla, J.; et al. Ganglion cell layer thinning in prodromal Alzheimer’s disease defined by amyloid PET. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2019, 5, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett-Young, A.; Ambler, A.; Cheyne, K.; Guiney, H.; Kokaua, J.; Steptoe, B.; Tham, Y.C.; Wilson, G.A.; Wong, T.Y.; Poulton, R. Associations between retinal nerve fiber layer and ganglion cell layer in middle age and cognition from childhood to adulthood. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022, 140, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An open-source Platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beretta, C.A.; Liu, S.; Stegemann, A.; Gan, Z.; Wang, L.; Linette, L.T.; Kuner, R. Quanty-cFOS, a novel ImageJ/Fiji algorithm for automated counting of immunoreactive cells in tissue sections. Cells 2023, 12, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Zeng, R.; Wu, G.; Hu, Y.; Yu, H. Beyond vision: A view from eye to Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2024, 11, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, P. Mechanisms of action of (n-3) fatty acids. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 592S–599S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Control | LSO | FO | Schizo | DHASCO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty acid composition (% of total fatty acids) | |||||

| Individual fatty acids | |||||

| 12:0 | 0.02 ± 0.04 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.03 |

| 13:0 | 0.18 ± 0.15 | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 0.18 ± 0.00 |

| 14:0 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 1.17 ± 0.03 | 2.04 ± 0.15 | 0.25 ± 0.02 |

| 16:0 | 12.39 ± 1.39 | 9.71 ± 0.01 | 11.39 ± 0.05 | 12.87 ± 0.18 | 9.62 ± 0.10 |

| 16:1n − 7 | 0.09 ± 0.08 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 2.07 ± 0.08 | 1.88 ± 0.13 | 0.08 ± 0.07 |

| 17:0 | 0.07 ± 0.06 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 0.10 ± 0.00 | 0.11 ± 0.00 | 0.05 ± 0.05 |

| 18:0 | 4.74 ± 0.22 | 4.70 ± 0.13 | 3.94 ± 0.04 | 3.84 ± 0.15 | 3.81 ± 0.02 |

| 18:1n − 9 | 22.72 ± 0.38 | 21.92 ± 0.41 | 21.20 ± 0.10 | 18.74 ± 0.43 | 18.47 ± 0.11 |

| 18:1n − 7 | 1.36 ± 0.04 | 1.15 ± 0.01 | 2.12 ± 0.03 | 2.63 ± 0.06 | 1.11 ± 0.01 |

| 18:2n − 6 | 50.67 ± 0.44 | 40.28 ± 0.10 | 38.12 ± 0.37 | 38.93 ± 0.59 | 40.51 ± 0.41 |

| 18:3n − 3 | 5.76 ± 0.18 | 20.07 ± 0.52 | 4.60 ± 0.05 | 4.46 ± 0.08 | 4.65 ± 0.06 |

| 18:4n − 3 | nd | 0.03 ± 0.05 | 0.54 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.03 | nd |

| 20:0 | nd | 0.30 ± 0.02 | 0.26 ± 0.01 | 0.30 ± 0.02 | 0.33 ± 0.00 |

| 20:1n − 9 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 2.92 ± 0.08 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ± 0.02 |

| 20:4n − 6 | nd | nd | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.04 | 0.18 ± 0.00 |

| 20:5n − 3 | nd | nd | 2.59 ± 0.09 | 0.42 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.10 |

| 22:0 | 0.35 ± 0.02 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 0.28 ± 0.00 | 0.30 ± 0.04 | 0.31 ± 0.01 |

| 22:5n − 6 | nd | nd | nd | 1.67 ± 0.05 | 3.37 ± 0.07 |

| 22:6n − 3 | nd | nd | 2.90 ± 0.09 | 10.01 ± 0.40 | 15.86 ± 0.37 |

| Sums and ratio of fatty acids | |||||

| SFA | 18.38 ± 1.44 | 15.44 ± 0.16 | 17.64 ± 0.03 | 19.98 ± 0.23 | 14.60 ± 0.14 |

| MUFA | 24.37 ± 0.43 | 23.35 ± 0.39 | 31.63 ± 0.16 | 23.52 ± 0.33 | 19.84 ± 0.11 |

| PUFA | 56.50 ± 0.51 | 60.43 ± 0.52 | 49.84 ± 0.20 | 55.75 ± 0.27 | 64.80 ± 0.15 |

| n − 3 PUFA | 5.76 ± 0.18 | 20.09 ± 0.54 | 11.24 ± 0.17 | 15.05 ± 0.43 | 20.71 ± 0.49 |

| n − 6 PUFA | 50.67 ± 0.44 | 40.30 ± 0.08 | 38.33 ± 0.36 | 40.65 ± 0.52 | 44.06 ± 0.35 |

| n − 3/n − 6 | 0.11 ± 0.00 | 0.50 ± 0.01 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 0.37 ± 0.01 | 0.47 ± 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pinho, M.S.; Ahfaz, H.; Carvalho, S.; Correia, J.; Spínola, M.; Pestana, J.M.; Bandarra, N.M.; Lopes, P.A. Retinal Degeneration in Alzheimer’s Disease 5xFAD Mice Fed DHA-Enriched Diets. Cells 2026, 15, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010008

Pinho MS, Ahfaz H, Carvalho S, Correia J, Spínola M, Pestana JM, Bandarra NM, Lopes PA. Retinal Degeneration in Alzheimer’s Disease 5xFAD Mice Fed DHA-Enriched Diets. Cells. 2026; 15(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010008

Chicago/Turabian StylePinho, Mário S., Husaifa Ahfaz, Sandra Carvalho, Jorge Correia, Maria Spínola, José M. Pestana, Narcisa M. Bandarra, and Paula A. Lopes. 2026. "Retinal Degeneration in Alzheimer’s Disease 5xFAD Mice Fed DHA-Enriched Diets" Cells 15, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010008

APA StylePinho, M. S., Ahfaz, H., Carvalho, S., Correia, J., Spínola, M., Pestana, J. M., Bandarra, N. M., & Lopes, P. A. (2026). Retinal Degeneration in Alzheimer’s Disease 5xFAD Mice Fed DHA-Enriched Diets. Cells, 15(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010008