Insulin Growth Factor Binding Protein-6 and the Liver

Highlights

- IGFBP-6 is a context-dependent regulator in the liver—enriched in stellate/cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF) compartments and shaped by lobular zonation—controlling IGF-II availability and exerting IGF-independent actions.

- Profibrotic, inflammatory, hypoxia/redox, and metabolic cues (including PTMs like O-GlcNAc) dynamically tune IGFBP-6 abundance and function across disease states and liver cancers.

- Research and clinical assays should shift from bulk abundance to function + location—PTM-aware proteomics, extracellular-vesicle profiling, and spatial readouts—to correctly interpret IGFBP-6 and IGF-II activity.

- Translational strategies include composite biomarkers and patient selection frameworks that use total/modified IGFBP-6 to guide IGF-axis therapies or microenvironment-targeted approaches.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The IGF Signaling Axis and IGFBP-6

2.1. Overview of the IGF-II Receptor Landscape

2.2. IGFBP-6: Dual IGF-Dependent and IGF-Independent Actions

3. IGFBP-6 in the Liver: Cellular Compartmentalization and Regulation

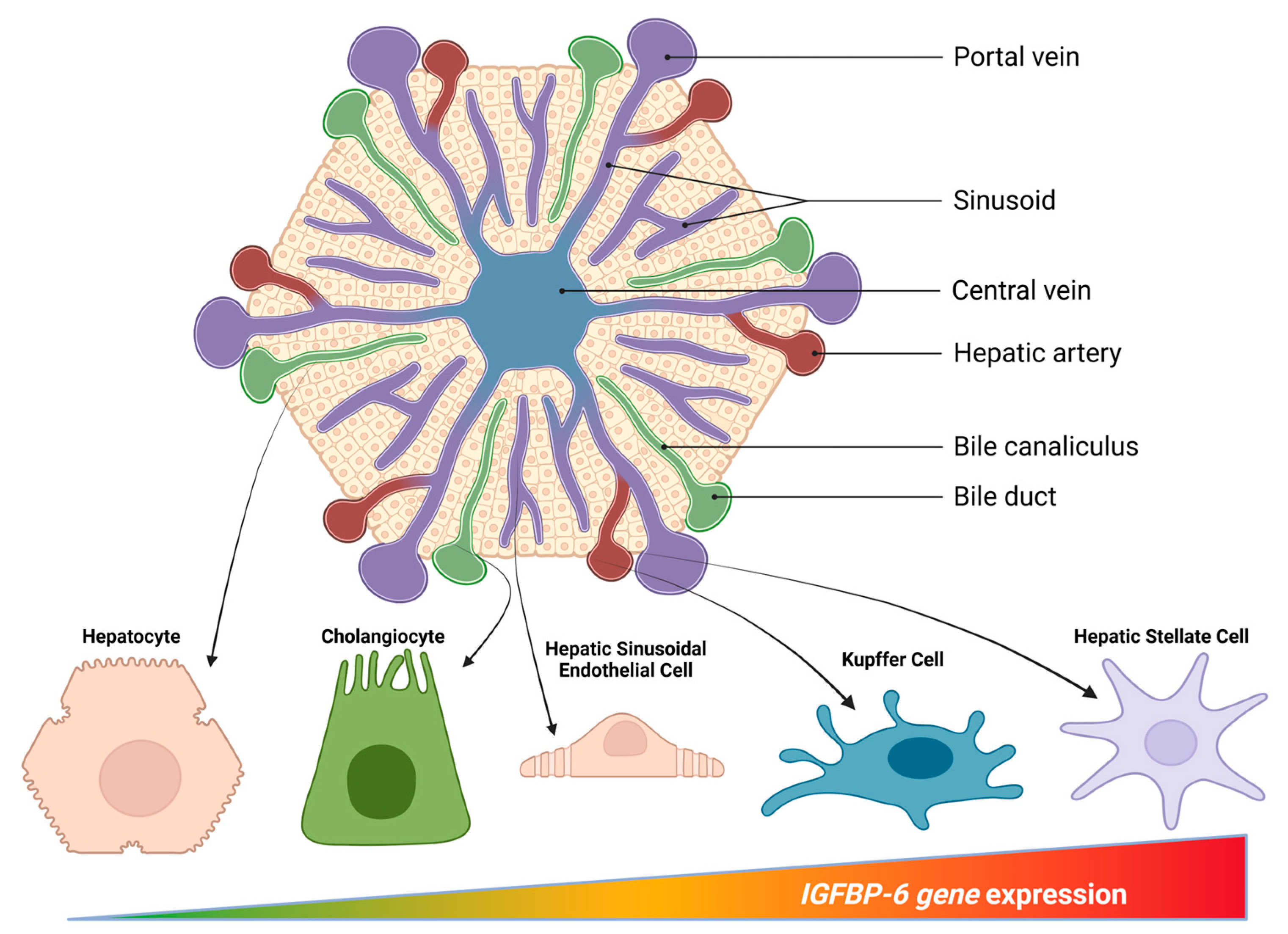

3.1. Cellular Sources Within the Hepatic Microenvironment

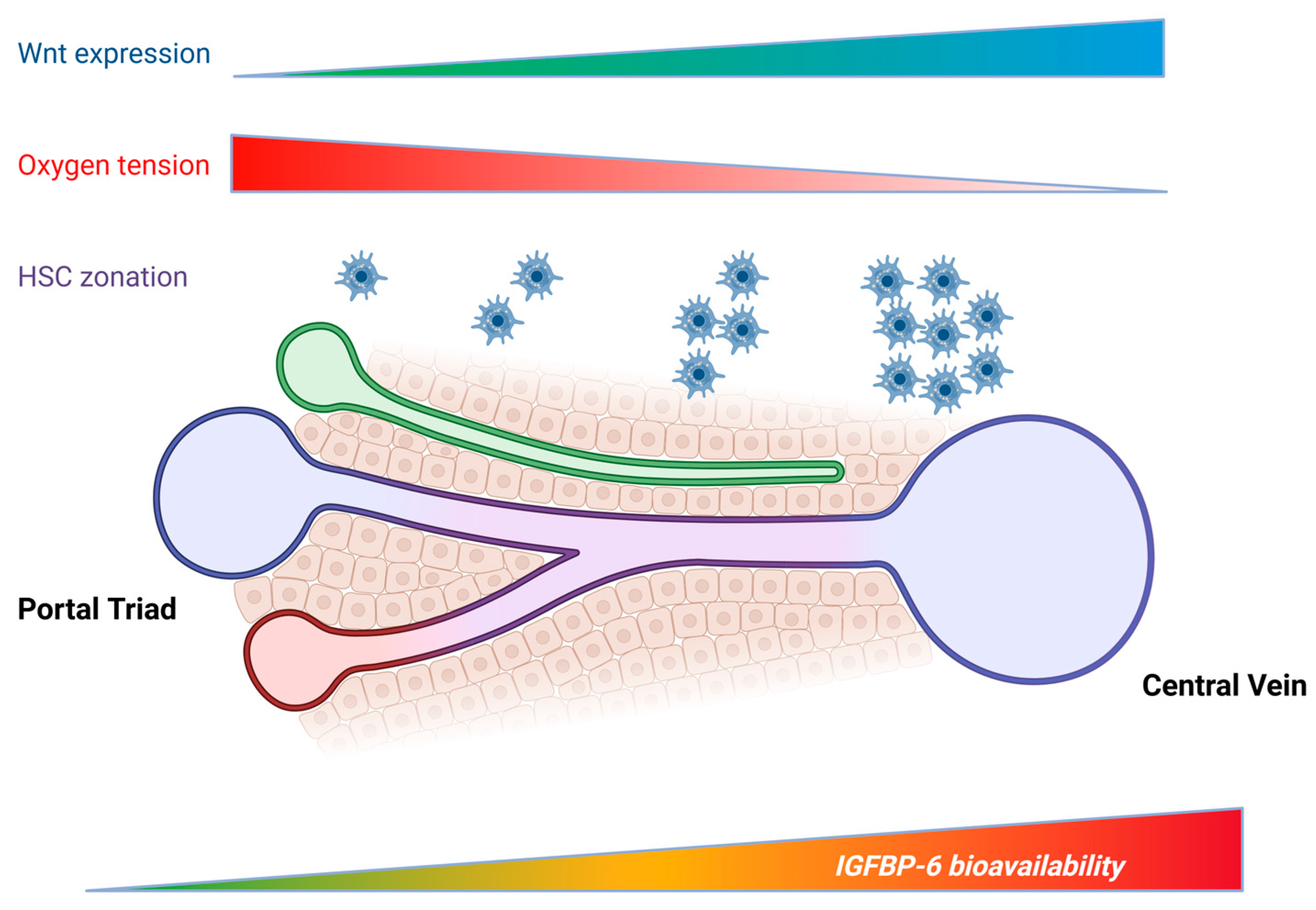

3.2. Spatial Context and Lobular Zonation

3.3. Regulation by Profibrotic, Metabolic, and Inflammatory Cues

3.3.1. TGF-β and Growth-Factor Programs in Stellate Cells

3.3.2. Inflammatory Cytokines and Innate Stimuli

3.3.3. Hypoxia, Redox Status, and HIF Signaling

3.3.4. Metabolic Cues and Nutrient Sensors

3.3.5. Post-Translational Modification and IGF-II Sequestration

3.3.6. Integration Across Pathways and Disease Stages

4. IGFBP-6 in Liver Diseases

4.1. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD)

4.2. Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease (ALD)

4.3. Viral Hepatitis

4.4. Cholestatic and Autoimmune Biliary Disease

4.5. Autoimmune Hepatitis

4.6. Cirrhosis, Portal Hypertension, and Systemic Decompensation

4.7. Hepatic Ischemia–Reperfusion (I/R)

4.8. Liver Regeneration

5. IGFBP-6 and Liver Cancers

5.1. IGFBP-6 and Hepatocellular Carcinoma

5.2. IGFBP-6 and Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

5.3. Translational Implications: Biomarkers, Patient Selection, and PTM-Aware Targeting

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IGFBP-6 | Insulin growth factor binding protein-6 |

| IGF | Insulin growth factor |

| TGF-β | Tumor growth factor-β |

| PDGF | Platelet-derived growth factor |

| PTM | Post-translational modification |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| AKT | Protein kinase B |

| RAS | Rat sarcoma |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| IGF-1R | IGF-1 receptor |

| CI-MPR | Cation-independent mannose-6-phosphate receptor |

| IR-A | Insulin receptor isoform A |

| TCF | T-cell factor |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia inducible factor-1α |

| LSEC | Liver sinusoidal endothelial cell |

| HSC | Hepatic stellate cell |

| aHSC | Activated hepatic stellate cell |

| qHSC | Quiescent hepatic stellate cell |

| CAF | Cancer-associated fibroblast |

| CCA | Cholangiocarcinoma |

| RSPO3 | R-spondin-3 |

| SMAD | Suppressor of mothers against decapentaplegic homolog |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1β |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| α-SMA | α-smooth muscle actin |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| IRE1 | Inositol requiring enzyme 1 |

| PDGFR | PDGF receptor |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor-κB |

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| MASLD | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease |

| MASH | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis |

| ALD | Alcohol-associated liver disease |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| PSC | Primary sclerosing cholangitis |

| I/R | Ischemia–reperfusion |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| GH | Growth hormone |

| PBC | Primary biliary cholangitis |

| AIH | Autoimmune hepatitis |

| HVPG | Hepatic venous-portal gradient |

| DAMP | Damage-associated molecular pattern |

| EV | Extracellular vesicle |

| PHx | Partial hepatectomy |

| LIHC | Liver hepatocellular carcinoma |

| iCCA | Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

References

- Annunziata, M.; Granata, R.; Ghigo, E. The IGF System. Acta Diabetol. 2011, 48, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollak, M. The Insulin and Insulin-like Growth Factor Receptor Family in Neoplasia: An Update. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 1, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.I.; Clemmons, D.R. Insulin-like Growth Factors and Their Binding Proteins: Biological Actions. Endocr. Rev. 1995, 16, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, R.C. Signaling Pathways of the Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Proteins. Endocr. Rev. 2023, 44, 753–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Moshe, S.; Itzkovitz, S. Spatial Heterogeneity in the Mammalian Liver. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aizarani, N.; Saviano, A.; Sagar; Mailly, L.; Durand, S.; Herman, J.S.; Pessaux, P.; Baumert, T.F.; Grün, D. A Human Liver Cell Atlas Reveals Heterogeneity and Epithelial Progenitors. Nature 2019, 572, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marx, V. Method of the Year: Spatially Resolved Transcriptomics. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, T.; Satija, R. Integrative Single-Cell Analysis. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R. The Biology and Function of Fibroblasts in Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 582–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahai, E.; Astsaturov, I.; Cukierman, E.; DeNardo, D.G.; Egeblad, M.; Evans, R.M.; Fearon, D.; Greten, F.R.; Hingorani, S.R.; Hunter, T.; et al. A Framework for Advancing Our Understanding of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perks, C.M. Role of the Insulin-like Growth Factor (IGF) Axis in Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samani, A.A.; Yakar, S.; LeRoith, D.; Brodt, P. The Role of the IGF System in Cancer Growth and Metastasis: Overview and Recent Insights. Endocr. Rev. 2007, 28, 20–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Yi, Z.; Wang, X.; Sun, J.; Li, L.; Wu, Q.; Chen, Y.; et al. Insulin-like Growth Factor 2 Drives Fibroblast-Mediated Tumor Immunoevasion and Confers Resistance to Immunotherapy. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, 14882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Shewy, H.M.; Luttrell, L.M. Chapter 24 Insulin-like Growth Factor-2/Mannose-6 Phosphate Receptors. Vitam. Horm. 2009, 80, 667–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Jones, E.Y.; Forbes, B.E. Chapter 25 Interactions of IGF-II with the IGF2R/Cation-Independent Mannose-6-Phosphate Receptor: Mechanism and Biological Outcomes. Vitam. Horm. 2009, 80, 699–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, L.J.; Misra, S.K.; Ishihara, M.; Battaile, K.P.; Grant, O.C.; Sood, A.; Woods, R.J.; Kim, J.J.P.; Tiemeyer, M.; Ren, G.; et al. Allosteric Regulation of Lysosomal Enzyme Recognition by the Cation-Independent Mannose 6-Phosphate Receptor. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, H. The IGF1 Signaling Pathway: From Basic Concepts to Therapeutic Opportunities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blyth, A.J.; Kirk, N.S.; Forbes, B.E. Understanding IGF-II Action Through Insights into Receptor Binding and Activation. Cells 2020, 9, 2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.K.; Westwood, M. Biology and Significance of Signalling Pathways Activated by IGF-II. Growth Factors 2012, 30, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.D.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, P.J.; Qin, S.R.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.C.; et al. The IGF2/IGF1R/Nanog Signaling Pathway Regulates the Proliferation of Acute Myeloid Leukemia Stem Cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvino, C.L.; Ong, S.C.; McNeil, K.A.; Delaine, C.; Booker, G.W.; Wallace, J.C.; Forbes, B.E. Understanding the Mechanism of Insulin and Insulin-like Growth Factor (IGF) Receptor Activation by IGF-II. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roghani, M.; Hossenlopp, P.; Lepage, P.; Balland, A.; Binoux, M. Isolation from Human Cerebrospinal Fluid of a New Insulin-like Growth Factor-Binding Protein with a Selective Affinity for IGF-II. FEBS Lett. 1989, 255, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboalola, D.; Han, V.K.M. Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein-6 Alters Skeletal Muscle Differentiation of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Stem Cells Int. 2017, 2017, 2348485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva, C.R.; Halloran, B.; Hjelmeland, A.B.; Vazquez, A.; Bailey, S.M.; Sarkaria, J.N.; Griguer, C.E. IGFBP6 Controls the Expansion of Chemoresistant Glioblastoma Through Paracrine IGF2/IGF-1R Signaling. Cell Commun. Signal. 2018, 16, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboalola, D.; Han, V.K.M. Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein-6 Promotes the Differentiation of Placental Mesenchymal Stem Cells into Skeletal Muscle Independent of Insulin-like Growth Factor Receptor-1 and Insulin Receptor. Stem Cells Int. 2019, 2019, 9245938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liso, A.; Capitanio, N.; Gerli, R.; Conese, M. From Fever to Immunity: A New Role for IGFBP-6? J. Cell Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 4588–4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, L.A.; Fu, P.; Yang, Z. Insulin-like Growth Factor-Binding Protein-6 and Cancer. Clin. Sci. 2013, 124, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, L.A. Recent Insights into the Actions of IGFBP-6. J. Cell Commun. Signal 2015, 9, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liso, A.; Venuto, S.; Coda, A.R.D.; Giallongo, C.; Alberto Palumbo, G.; Tibullo, D. IGFBP-6: At the Crossroads of Immunity, Tissue Repair and Fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, P.; Yang, Z.; Bach, L.A. Prohibitin-2 Binding Modulates Insulin-like Growth Factor-Binding Protein-6 (IGFBP-6)-Induced Rhabdomyosarcoma Cell Migration. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 29890–29900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Jin, Z.; Liu, Z.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, J.; Fang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Ning, B. Pantothenic Acid Ameliorates Hepatic Fibrosis by Targeting IGFBP6 to Regulate the TGF-β/SMADs Pathway. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, N.; Zhang, J.; Huqun; Miyazawa, H.; Tanaka, T.; Su, X.; Hagiwara, K. Identification of IGFBP-6 as an Effector of the Tumor Suppressor Activity of SEMA3B. Oncogene 2008, 27, 6581–6589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denys, H.; Jadidizadeh, A.; Nik, S.A.; Van Dam, K.; Aerts, S.; Alman, B.A.; Cassiman, J.J.; Tejpar, S. Identification of IGFBP-6 as a Significantly Downregulated Gene by β-Catenin in Desmoid Tumors. Oncogene 2004, 23, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lu, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Y.; Fu, P.; Gallicchio, M.A.; Bach, L.A.; Duan, C. IGF Binding Protein-6 Expression in Vascular Endothelial Cells Is Induced by Hypoxia and Plays a Negative Role in Tumor Angiogenesis. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 130, 2003–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacParland, S.A.; Liu, J.C.; Ma, X.Z.; Innes, B.T.; Bartczak, A.M.; Gage, B.K.; Manuel, J.; Khuu, N.; Echeverri, J.; Linares, I.; et al. Single Cell RNA Sequencing of Human Liver Reveals Distinct Intrahepatic Macrophage Populations. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Human Protein Atlas. Available online: https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000167779-IGFBP6/Single%2Bcell/Liver (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Gentilini, A.; Feliers, D.; Pinzani, M.; Woodruff, K.; Abboud, S. Characterization and Regulation of Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Proteins in Human Hepatic Stellate Cells. J. Cell Physiol. 1998, 174, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Kim, S.Y.; Adewale, F.; Zhou, Y.; Aldler, C.; Ni, M.; Wei, Y.; Burczynski, M.E.; Atwal, G.S.; Sleeman, M.W.; et al. Single-Cell RNA Transcriptome Landscape of Hepatocytes and Non-Parenchymal Cells in Healthy and NAFLD Mouse Liver. iScience 2021, 24, 103233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montori, M.; Scorzoni, C.; Argenziano, M.E.; Balducci, D.; De Blasio, F.; Martini, F.; Buono, T.; Benedetti, A.; Marzioni, M.; Maroni, L. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in Cholangiocarcinoma: Current Knowledge and Possible Implications for Therapy. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remsing Rix, L.L.; Sumi, N.J.; Hu, Q.; Desai, B.; Bryant, A.T.; Li, X.; Welsh, E.A.; Fang, B.; Kinose, F.; Kuenzi, B.M.; et al. IGF-Binding Proteins Secreted by Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Induce Context-Dependent Drug Sensitization of Lung Cancer Cells. Sci. Signal. 2022, 15, eabj5879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caligiuri, A.; Parola, M.; Marra, F.; Cannito, S.; Gentilini, A. Cholangiocarcinoma Tumor Microenvironment Highlighting Fibrosis and Matrix Components. Hepatoma Res. 2023, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iosef, C.; Gkourasas, T.; Jia, C.Y.H.; Li, S.S.C.; Han, V.K.M. A Functional Nuclear Localization Signal in Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein-6 Mediates Its Nuclear Import. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 1214–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conese, M.; Pace, L.; Pignataro, N.; Catucci, L.; Ambrosi, A.; Di Gioia, S.; Tartaglia, N.; Liso, A. Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein 6 Is Secreted in Extracellular Vesicles upon Hyperthermia and Oxidative Stress in Dendritic Cells but Not in Monocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, R.P.; Porat-Shliom, N. Liver Zonation—Revisiting Old Questions with New Technologies. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 732929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, J.; Henderson, N.C. Liver Zonation, Revisited. Hepatology 2022, 76, 1219–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, C.; Monga, S.P.; Nejak-Bowen, K. Role and Regulation of Wnt/β-Catenin in Hepatic Perivenous Zonation and Physiological Homeostasis. Am. J. Pathol. 2022, 192, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kietzmann, T. Metabolic Zonation of the Liver: The Oxygen Gradient Revisited. Redox Biol. 2017, 11, 622–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kietzmann, T. Liver Zonation in Health and Disease: Hypoxia and Hypoxia-Inducible Transcription Factors as Concert Masters. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, A.; Saito, Y.; Wang, G.; Sun, Q.; Yin, C.; Lee, K.H.; Geng, Y.; Rajbhandari, P.; Hernandez, C.; Steffani, M.; et al. Hepatic Stellate Cells Control Liver Zonation, Size and Functions via R-Spondin 3. Nature 2025, 640, 752–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, F.; Andersson, A.; Saarenpää, S.; Larsson, L.; Van Hul, N.; Kanatani, S.; Masek, J.; Ellis, E.; Barragan, A.; Mollbrink, A.; et al. Spatial Transcriptomics to Define Transcriptional Patterns of Zonation and Structural Components in the Mouse Liver. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 7046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakubovsky, O.; Afriat, A.; Egozi, A.; Halpern, K.B.; Barkai, T.; Harnik, Y.; Kohanim, Y.K.; Novoselsky, R.; Golani, O.; Goliand, I.; et al. A Spatial Transcriptomics Atlas of Live Donors Reveals Unique Zonation Patterns in the Healthy Human Liver. BioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LISTA: LIver Spatio-Temporal Atlas. Available online: https://db.cngb.org/stomics/lista/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Duc, P.M.; Thuy, L.T.T.; Hai, H.; Ha, N.T.; Anh, P.T.; Ikenaga, H.; Fuji, H.; Yuasa, H.; Matsubara, T.; Huyen, V.T.; et al. A Single-Cell Fixed RNA Profiling of Liver Fibrosis Progression and Regression Reveals SEMA4D and LMCD1 as Key Mediators of Fibrogenesis. BioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wen, X.M.; Lui, E.L.H.; Friedman, S.L.; Cui, W.; Ho, N.P.S.; Li, L.; Ye, T.; Fan, S.T.; Zhang, H. Therapeutic Targeting of the PDGF and TGF-Β-Signaling Pathways in Hepatic Stellate Cells by PTK787/ZK22258. Lab. Investig. 2009, 89, 1152–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Tsushima, T.; Miyakawa, M.; Isozaki, O.; Yamada, H.; Xu, Z.R.; Iwamoto, Y. Effect of Cytokines on Production of Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Proteins (IGFBPs) from Human Fibroblasts in Culture. Endocr. J. 1999, 46, S63–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liso, A.; Castellani, S.; Massenzio, F.; Trotta, R.; Pucciarini, A.; Bigerna, B.; De Luca, P.; Zoppoli, P.; Castiglione, F.; Palumbo, M.C.; et al. Human Monocyte-Derived Dendritic Cells Exposed to Hyperthermia Show a Distinct Gene Expression Profile and Selective Upregulation of IGFBP6. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 60826–60840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laselva, O.; Criscione, M.L.; Allegretta, C.; Di Gioia, S.; Liso, A.; Conese, M. Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein (IGFBP-6) as a Novel Regulator of Inflammatory Response in Cystic Fibrosis Airway Cells. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 905468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longhitano, L.; Tibullo, D.; Vicario, N.; Giallongo, C.; La Spina, E.; Romano, A.; Lombardo, S.; Moretti, M.; Masia, F.; Coda, A.R.D.; et al. IGFBP-6/Sonic Hedgehog/TLR4 Signalling Axis Drives Bone Marrow Fibrotic Transformation in Primary Myelofibrosis. Aging 2021, 13, 25055–25071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minchenko, O.H.; Kharkova, A.P.; Minchenko, D.O.; Karbovskyi, L.L. Effect of Hypoxia on the Expression of Genes That Encode Some IGFBP and CCN Proteins in U87 Glioma Cells Depends on IRE1 Signaling. Ukr. Biochem. J. 2015, 87, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coda, A.R.D.; Liso, A.; Bellanti, F. Redox Biology and Insulin-like Growth Factor-Binding Protein-6: A Potential Relationship. Biology 2025, 14, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhitano, L.; Vicario, N.; Forte, S.; Giallongo, C.; Broggi, G.; Caltabiano, R.; Barbagallo, G.M.V.; Altieri, R.; Raciti, G.; Di Rosa, M.; et al. Lactate Modulates Microglia Polarization via IGFBP6 Expression and Remodels Tumor Microenvironment in Glioblastoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2023, 72, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannaerts, I.; Schroyen, B.; Verhulst, S.; Van Lommel, L.; Schuit, F.; Nyssen, M.; Van Grunsven, L.A. Gene Expression Profiling of Early Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation Reveals a Role for Igfbp3 in Cell Migration. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e84071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Ding, M.; Zhou, H.; Li, X. Epigenetic Modification in Liver Fibrosis: Promising Therapeutic Direction with Significant Challenges Ahead. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 14, 1009–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Shabbiri, K.; Ijaz, B.; Asad, S.; Nazar, N.; Nazar, S.; Fouzia, K.; Kausar, H.; Gull, S.; Sarwar, M.T.; et al. Serine 204 Phosphorylation and O-GlcNAC Interplay of IGFBP-6 as Therapeutic Indicator to Regulate IGF-II Functions in Viral Mediated Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Virol. J. 2011, 8, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, L.A. Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein-6: The “forgotten” Binding Protein? Horm. Metab. Res. 1999, 31, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, T.L.; Fourman, L.T.; Zheng, I.; McClure, C.M.; Feldpausch, M.N.; Torriani, M.; Corey, K.E.; Chung, R.T.; Lee, H.; Kleiner, D.E.; et al. Relationship of IGF-1 and IGF-Binding Proteins to Disease Severity and Glycemia in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, e520–e533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosique-Oramas, D.; Martínez-Castillo, M.; Raya, A.; Medina-Ávila, Z.; Aragón, F.; Limón-Castillo, J.; Hernández-Barragán, A.; Santoyo, A.; Montalvo-Javé, E.; Pérez-Hernández, J.L.; et al. Production of Insulin-like Growth Factor-Binding Proteins during the Development of Hepatic Fibrosis Due to Chronic Hepatitis C. Rev. Gastroenterol. México (Engl. Ed.) 2020, 85, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, M.; Joenväärä, S.; Saraswat, M.; Tohmola, T.; Saarela, T.; Tenca, A.; Arola, J.; Renkonen, R.; Färkkilä, M. Quantitative Bile and Serum Proteomics for the Screening and Differential Diagnosis of Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A.H.; Ytting, H.; Nielsen, A.B.; Werge, M.P.; Rashu, E.B.; Hetland, L.E.; Thing, M.; Nabilou, P.; Burisch, J.; Junker, A.E.; et al. Diagnostics of Autoimmune Hepatitis Enabled by Non-Invasive Clinical Proteomics. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 62, 901–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach, L.A. Current Ideas on the Biology of IGFBP-6: More than an IGF-II Inhibitor? Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2016, 30–31, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinella, M.E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Ratziu, V.; Francque, S.M.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kanwal, F.; Romero, D.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Anstee, Q.M.; Arab, J.P.; et al. A Multisociety Delphi Consensus Statement on New Fatty Liver Disease Nomenclature. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 1966–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacke, F.; Horn, P.; Wai-Sun Wong, V.; Ratziu, V.; Bugianesi, E.; Francque, S.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Valenti, L.; Roden, M.; Schick, F.; et al. EASL–EASD–EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). J. Hepatol. 2024, 81, 492–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.K.; Bansal, M.B. Pathogenesis of MASLD and MASH—Role of Insulin Resistance and Lipotoxicity. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 59, S10–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourman, L.T.; Billingsley, J.M.; Agyapong, G.; Ho Sui, S.J.; Feldpausch, M.N.; Purdy, J.; Zheng, I.; Pan, C.S.; Corey, K.E.; Torriani, M.; et al. Effects of Tesamorelin on Hepatic Transcriptomic Signatures in HIV-Associated NAFLD. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e140134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourman, L.T.; Stanley, T.L.; Billingsley, J.M.; Sui, S.J.H.; Feldpausch, M.N.; Boutin, A.; Zheng, I.; McClure, C.M.; Corey, K.E.; Torriani, M.; et al. Delineating Tesamorelin Response Pathways in HIV-Associated NAFLD Using a Targeted Proteomic and Transcriptomic Approach. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, A.; Arians, M.; Burg-Roderfeld, M.; Karrasch, T.; Schäffler, A.; Roderfeld, M.; Roeb, E. Circulating Adipokines and Hepatokines Serve as Diagnostic Markers during Obesity Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabb, D.W.; Im, G.Y.; Szabo, G.; Mellinger, J.L.; Lucey, M.R. Diagnosis and Treatment of Alcohol-Associated Liver Diseases: 2019 Practice Guidance From the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2020, 71, 306–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackowiak, B.; Fu, Y.; Maccioni, L.; Gao, B. Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedić, O.; Nikolić, J.A.; Hajduković-Dragojlović, L.; Todorović, V.; Masnikosa, R. Alterations of IGF-Binding Proteins in Patients with Alcoholic Liver Cirrhosis. Alcohol. 2000, 21, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.H.; Doiron, K.; Patterson, A.D.; Gonzalez, F.J.; Fornace, A.J. Identification of Serum Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein 1 as Diagnostic Biomarker for Early-Stage Alcohol-Induced Liver Disease. J. Transl. Med. 2013, 11, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arab, J.P.; Cabrera, D.; Sehrawat, T.S.; Jalan-Sakrikar, N.; Verma, V.K.; Simonetto, D.; Cao, S.; Yaqoob, U.; Leon, J.; Freire, M.; et al. Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation Promotes Alcohol-Induced Steatohepatitis through Igfbp3 and SerpinA12. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzak, A.; Adamek, A. The Insulin-like Growth Factor (IGF) Signaling Axis and Hepatitis C Virus-Associated Carcinogenesis (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2012, 41, 1919–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschfield, G.M.; Beuers, U.; Corpechot, C.; Invernizzi, P.; Jones, D.; Marzioni, M.; Schramm, C. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: The Diagnosis and Management of Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. J. Hepatol. 2017, 67, 145–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlus, C.L.; Arrivé, L.; Bergquist, A.; Deneau, M.; Forman, L.; Ilyas, S.I.; Lunsford, K.E.; Martinez, M.; Sapisochin, G.; Shroff, R.; et al. AASLD Practice Guidance on Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis and Cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology 2023, 77, 659–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, A.; Ma, X.; Takahashi, A.; Vierling, J.M. Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Lancet 2024, 404, 1053–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalekos, G.; Gatselis, N.; Drenth, J.P.; Heneghan, M.; Jørgensen, M.; Lohse, A.W.; Londoño, M.; Muratori, L.; Papp, M.; Samyn, M.; et al. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Autoimmune Hepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2025, 83, 453–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saghir, S.A.M.; Al Hroob, A.M.; Alshehade, S.A.; Alnaimat, S.; Al Yousfi, N.A.; Al-Rawashdeh, S.A.B.; Al Rawashdeh, M.A.; Alshawsh, M.A. Proteomic Approaches for Biomarker Discovery and Clinical Applications in Autoimmune Diseases. Clin. Chim. Acta 2026, 578, 120533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guixé-Muntet, S.; Quesada-Vázquez, S.; Gracia-Sancho, J. Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Options for Cirrhotic Portal Hypertension. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 9, 646–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, R.; Cao, S.; Shah, V.H. The Pathophysiology of Portal Hypertension. Clin. Liver Dis. 2024, 28, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotani, K.; Kawada, N. Recent Advances in the Pathogenesis and Clinical Evaluation of Portal Hypertension in Chronic Liver Disease. Gut Liver 2024, 18, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, S.; Danielsen, K.V.; Hobolth, L.; Mortensen, C.; Kimer, N. Diagnosis of Portal Hypertension. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assy, N.; Pruzansky, Y.; Gaitini, D.; Shen Orr, Z.; Hochberg, Z.; Baruch, Y. Growth Hormone-Stimulated IGF-1 Generation in Cirrhosis Reflects Hepatocellular Dysfunction. J. Hepatol. 2008, 49, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, C.G.; Colombo, B.d.S.; Ronsoni, M.F.; e Silva, P.E.S.; Fayad, L.; Silva, T.E.; Wildner, L.M.; Bazzo, M.L.; Dantas-Correa, E.B.; Narciso-Schiavon, J.L.; et al. Circulating Insulin-like Growth Factor-Binding Protein 3 as Prognostic Biomarker in Liver Cirrhosis. World J. Hepatol. 2016, 8, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartl, L.; Schwarz, M.; Simbrunner, B.; Jachs, M.; Wolf, P.; Bauer, D.J.M.; Scheiner, B.; Balcar, L.; Semmler, G.; Hofer, B.S.; et al. Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 in Cirrhosis Is Linked to Hepatic Dysfunction and Fibrogenesis and Predicts Liver-related Mortality. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 61, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, C.; Yaqoob, U.; Lu, J.; Xie, M.; Anwar, A.; Jalan-Sakrikar, N.; Jerez, S.; Sehrawat, T.S.; Navarro-Corcuera, A.; Kostallari, E.; et al. Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells Contribute to Portal Hypertension through Collagen Type IV–Driven Sinusoidal Remodeling. JCI Insight 2024, 9, e174775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, C.; Jiménez-Castro, M.B.; Gracia-Sancho, J. Hepatic Ischemia and Reperfusion Injury: Effects on the Liver Sinusoidal Milieu. J. Hepatol. 2013, 59, 1094–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.L.; Cai, Y.; Chen, Y.H.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, X.X.; Ye, L.P.; Li, S.W. Novel Targets and Therapeutic Strategies to Protect Against Hepatic Ischemia Reperfusion Injury. Front. Med. 2022, 8, 757336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Palmer, A.; Lupu, L.; Huber-Lang, M. Inflammatory Response to the Ischaemia–Reperfusion Insult in the Liver after Major Tissue Trauma. Eur. J. Trauma. Emerg. Surg. 2022, 48, 4431–4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Koh, H.W.; Bae, U.J.; Park, B.H. Aggravation of Post-Ischemic Liver Injury by Overexpression of Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein 3. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tazuke, S.I.; Mazure, N.M.; Sugawara, J.; Carland, G.; Faessen, G.H.; Suen, L.F.; Irwin, J.C.; Powell, D.R.; Giaccia, A.J.; Giudice, L.C. Hypoxia Stimulates Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein 1 (IGFBP-1) Gene Expression in HepG2 Cells: A Possible Model for IGFBP-1 Expression in Fetal Hypoxia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 10188–10193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taub, R. Transcriptional Control of Liver Regeneration. FASEB J. 1996, 10, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, A.I.; Guidotti, L.G.; Pezacki, J.P.; Chisari, F.V.; Schultz, P.G. Gene Expression during the Priming Phase of Liver Regeneration after Partial Hepatectomy in Mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 11181–11186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korchilava, B.; Khachidze, T.; Megrelishvili, N.; Svanadze, L.; Kakabadze, M.; Tsomaia, K.; Jintcharadze, M.; Kordzaia, D. Liver Regeneration after Partial Hepatectomy: Triggers and Mechanisms. World J. Hepatol. 2025, 17, 107378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, F.; Köhler, U.A.; Speicher, T.; Werner, S. Regulation of Liver Regeneration by Growth Factors and Cytokines. EMBO Mol. Med. 2010, 2, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leu, J.I.; Crissey, M.A.S.; Leu, J.P.; Ciliberto, G.; Taub, R. Interleukin-6-Induced STAT3 and AP-1 Amplify Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 1-Mediated Transactivation of Hepatic Genes, an Adaptive Response to Liver Injury. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001, 21, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demori, I.; Balocco, S.; Voci, A.; Fugassa, E. Increased Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein-4 Expression after Partial Hepatectomy in the Rat. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2000, 278, G384–G389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leu, J.I.; Crissey, M.A.S.; Craig, L.E.; Taub, R. Impaired Hepatocyte DNA Synthetic Response Posthepatectomy in Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein 1-Deficient Mice with Defects in C/EBPβ and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase/Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase Regulation. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 23, 1251–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Human Protein Atlas. Available online: https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000167779-IGFBP6/cancer (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Enguita-Germán, M.; Fortes, P. Targeting the Insulin-like Growth Factor Pathway in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. World J. Hepatol. 2014, 6, 716–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Wang, S.; Xia, L.; Sun, Z.; Chan, K.M.; Bernards, R.; Qin, W.; Chen, J.; Xia, Q.; Jin, H. Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Signaling Pathways and Therapeutic Advances. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Chua, M.S.; Yang, D.; Tsalenko, A.; Peter, B.J.; So, S. Antibody Arrays Identify Potential Diagnostic Markers of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Biomark. Insights 2008, 3, BMI.S595-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, B.; Qian, Y.; Liu, F. IGF1/IGF1R Signaling Promotes the Expansion of Liver CSCs and Serves as a Potential Therapeutic Target in HCC. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, H.; Wan, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Ge, C.; Liu, Y.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, D.; Shi, G.; et al. Single-Cell Transcriptomic Architecture and Intercellular Crosstalk of Human Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 1118–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, D.; Ben-Shmuel, A.; Erez, N.; Scherz-Shouval, R. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in the Single-Cell Era. Nat. Cancer 2022, 3, 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Liu, E.; Zong, Y.; Yu, W.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, J.; Gu, M.; Meng, Z.; Li, J.; et al. Deciphering Cholangiocarcinoma Heterogeneity and Specific Progenitor Cell Niche of Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma at Single-Cell Resolution. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 18, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Stimulus/Context | Model/Cell Type | Direction on IGFBP-6 | Mechanism/Pathway | Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGF-β (fibrogenic cue) | Primary and cultured HSCs (mouse/human) | ↑ | SMAD2/3 signaling | Fibrosis-linked effector in HSCs | [31] |

| PDGF/profibrotic growth-factor milieu | HSC activation | ↑ (inferred) | PDGFR–ERK/PI3K programs that co-activate HSC secretome | Supports inclusion of IGFBP-6 in growth-factor-responsive HSC programs | [54] |

| IL-1β, TNF (inflammatory cytokines) | Human stromal/epithelial systems | ↑ | NF-κB/inflammatory transcription | Non-hepatic primary data; plausible in liver injury | [29] |

| LPS/innate trigger with IGFBP-6 neutralization | Epithelial/immune models | Modulatory (loss → ↑ inflammatory genes) | Feedback control of cytokine programs | Suggests IGFBP-6 restrains excessive inflammation | [57] |

| Hypoxia | Human endothelium | ↑ | HIF-1-dependent transcription | Likely relevant to LSECs/pericentral zones | [34] |

| ER stress/IRE1 arm under hypoxia | Non-hepatic cells | ↑ | IRE1/XBP1-linked stress response | Converges with hypoxia in injured liver | [59] |

| Redox/oxidative stress linkage | Multi-tissue synthesis | Context-dependent | Redox-sensitive regulatory networks | Places IGFBP-6 within immune-fibrotic redox circuits | [60] |

| Lactate/metabolic reprogramming | Human immune cells | ↑/reprograms function | Metabolic–transcriptional coupling | Route by which lipotoxic/steatotic liver may tune IGFBP-6 | [61] |

| Early metabolic activation of HSCs | Cultured HSCs | Family shift (incl. IGFBPs) | Metabolic–ERK/AKT pathways | Supports nutrient/state sensitivity of IGFBP programs | [62] |

| O-GlcNAc at Ser204 (viral hepatitis) | HBV/HCV contexts; biochemical assays | ↓ IGF-II affinity (functional) | Hexosamine pathway → O-GlcNAcylation | Alters sequestration without requiring transcriptional change | [64] |

| Disease/Context | Core Pathogenesis | IGFBP-6 Signal | Stage Dependence | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MASLD/MASH | Insulin resistance, lipotoxicity, immune–stromal activation → steatohepatitis/fibrosis | Cohort profiling shows associations of IGFBP-6 with histologic severity within the IGFBP family | Likely (signals track steatosis/inflammation severity) | [66] |

| ALD | Ethanol/acetaldehyde toxicity, gut–liver axis, ROS, HSC activation | No dedicated IGFBP-6 measurements in classic ALD studies (axis-level changes reported, IGFBP-6 usually absent) | Unknown | - |

| Chronic viral hepatitis | Persistent viral antigens and immune injury → fibrosis | In HCV, IGFBP-6 varies with fibrosis (↑ at F3–F4 vs. controls); in HBV/HCV, O-GlcNAc(Ser204) on IGFBP-6 reduces IGF-II binding | Yes (fibrosis-linked in HCV) | [67] |

| Cholestatic/autoimmune biliary disease | Immune-mediated bile-duct injury, cholestasis, portal fibro-inflammation | Large PSC proteomics: IGFBP-6 not among top discriminatory markers (signal likely subtle/compartmental) | Unclear | [68] |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | Loss of tolerance → T-cell-mediated interface hepatitis | IGFBP-6 not consistently included in recent ML proteomic panels | Unclear | [69] |

| Hepatic ischemia–reperfusion | Ischemia → reperfusion ROS, neutrophils, endothelium activation, DAMPs | IGFBP-6 not yet profiled in I/R cohorts; mechanistic review places IGFBP-6 in redox/immune programs relevant to I/R | Time-locked effects expected | [60] |

| Liver regeneration | IL-6/STAT3 priming → proliferation → redifferentiation | IGFBP-6 kinetics not defined; plausibility from IGFBP-6 repair biology | Time-dependent, but unknown | [60,70] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Coda, A.R.D.; Kasperczyk, S.; Dobrakowski, M.; Kasperczyk, A.; Trecca, M.I.; Liso, A.; Serviddio, G.; Bellanti, F. Insulin Growth Factor Binding Protein-6 and the Liver. Cells 2026, 15, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010077

Coda ARD, Kasperczyk S, Dobrakowski M, Kasperczyk A, Trecca MI, Liso A, Serviddio G, Bellanti F. Insulin Growth Factor Binding Protein-6 and the Liver. Cells. 2026; 15(1):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010077

Chicago/Turabian StyleCoda, Anna Rita Daniela, Sławomir Kasperczyk, Michał Dobrakowski, Aleksandra Kasperczyk, Maria Incoronata Trecca, Arcangelo Liso, Gaetano Serviddio, and Francesco Bellanti. 2026. "Insulin Growth Factor Binding Protein-6 and the Liver" Cells 15, no. 1: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010077

APA StyleCoda, A. R. D., Kasperczyk, S., Dobrakowski, M., Kasperczyk, A., Trecca, M. I., Liso, A., Serviddio, G., & Bellanti, F. (2026). Insulin Growth Factor Binding Protein-6 and the Liver. Cells, 15(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010077