Preclinical PET and SPECT Imaging in Small Animals: Technologies, Challenges and Translational Impact

Highlights

- Advances in PET and SPECT technology significantly improved spatial resolution, sensitivity and quantitative accuracy in small-animal imaging.

- Experimental conditions and QC procedures critically affect data reliability and reproducibility in preclinical molecular imaging.

- Enhanced imaging performance increases the translational value of animal models by enabling more precise assessment of biological processes relevant to human disease.

- Technological progress in multimodal and hybrid systems expands the scope of preclinical research, allowing comprehensive functional–anatomical assessment within a single imaging workflow.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Fundamentals of Preclinical PET and SPECT

2.1. Principles of Nuclear Imaging

2.2. Radionuclides and Radiopharmaceuticals Used in PET and SPECT

2.3. Emerging Theranostic Radionuclide Platforms for Preclinical Imaging and Therapy

2.4. Physical Determinants of Image Formation

2.5. Biological Considerations in Tracer Use

3. Preclinical PET and SPECT Instrumentation and Technological Development

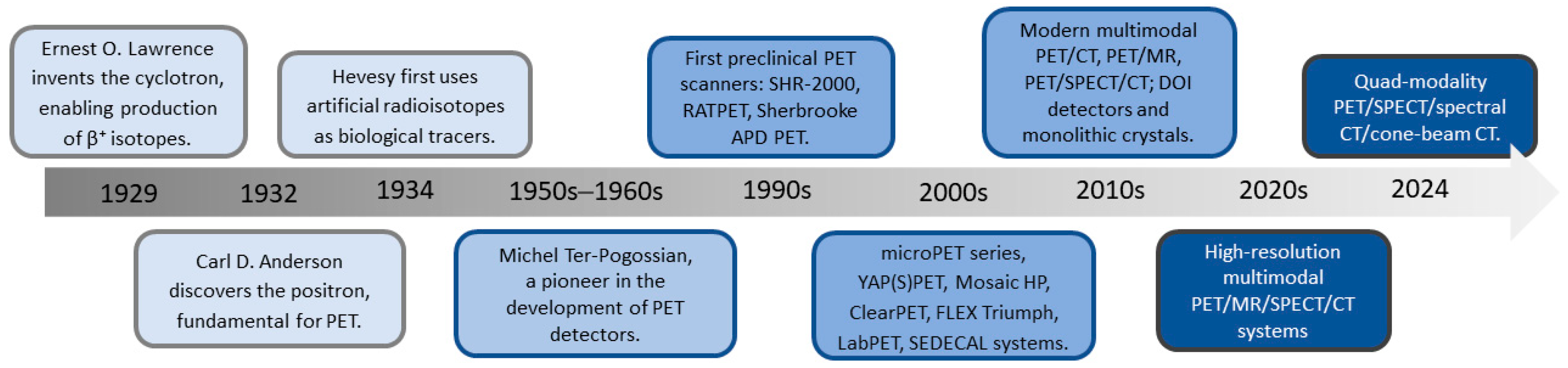

3.1. Evolution of Preclinical PET Technology

3.2. Physical Determinants of PET Resolution and Accuracy in Multimodal Imaging

3.3. Evolution of Preclinical SPECT Technology

3.4. Physical and Methodological Factors Affecting Quantification in Preclinical SPECT

3.5. Advances in Multimodal, Hybrid, and Quad-Modality Imaging Platforms in Preclinical PET and SPECT

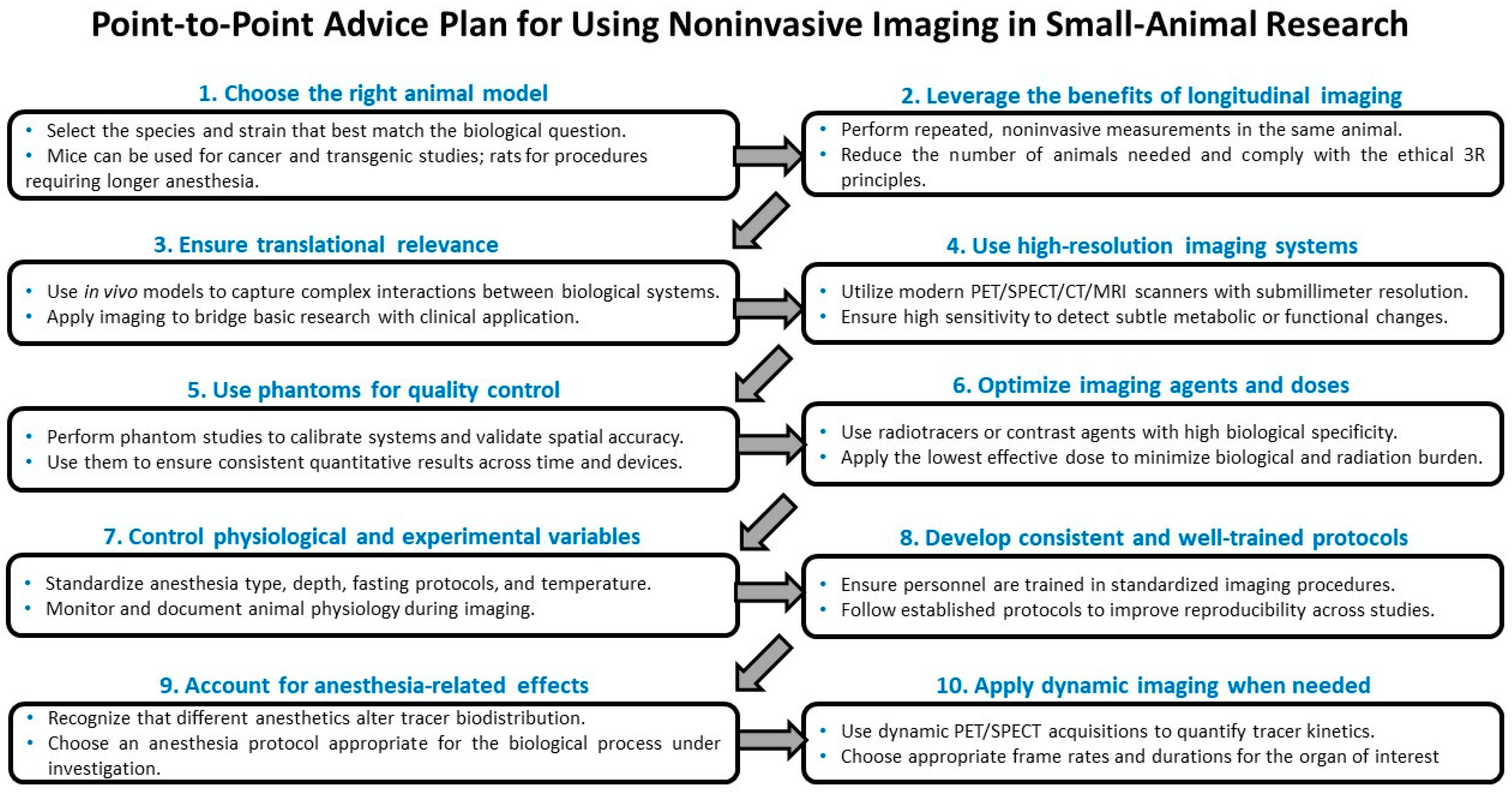

4. Applications of Noninvasive Imaging in Small-Animal Models

4.1. Role of Small-Animal Models in Biomedical Research

4.2. Longitudinal Imaging and Ethical Advantages

4.3. Translational Relevance and Model Selection

4.4. Physiological Factors Influencing Imaging Outcomes

4.5. Representative Methodological Examples: FDG Biodistribution, Anesthetic Effects, and Dynamic Acquisition Strategies

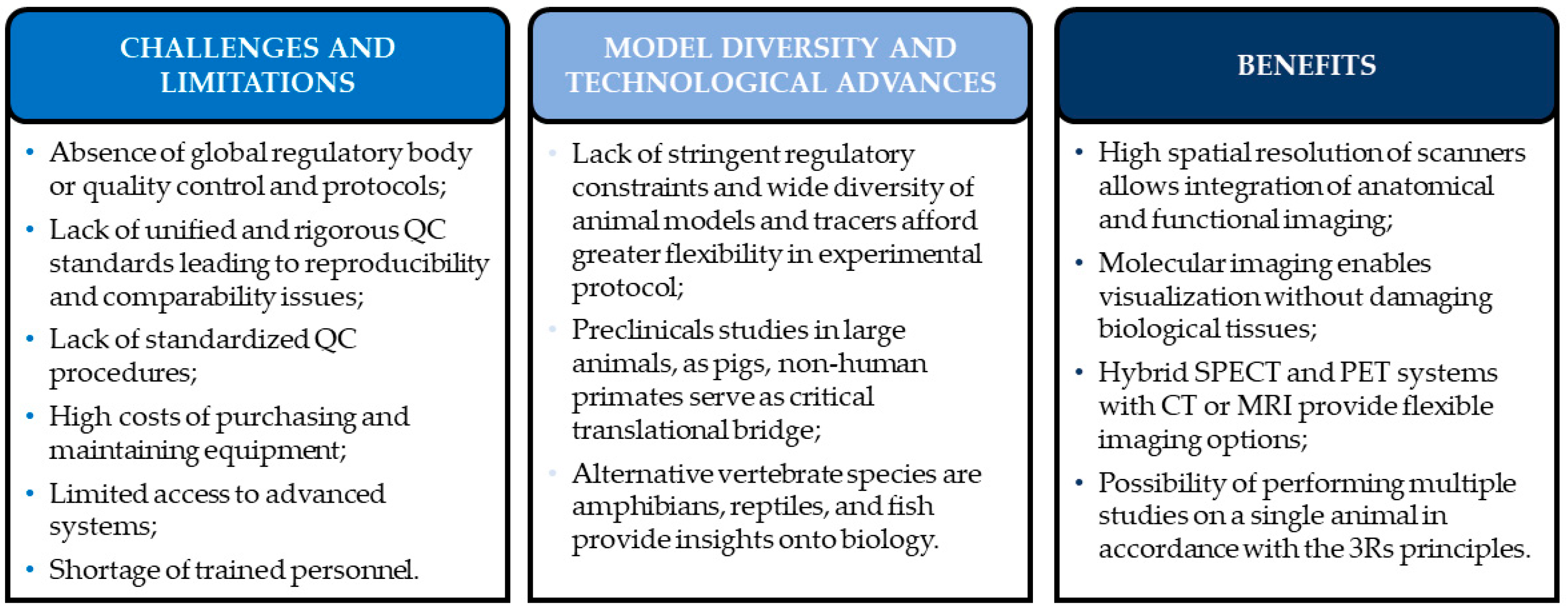

5. Challenges, Limitations and Benefits in Preclinical Imaging Studies

5.1. Limitations of Preclinical Imaging Studies

5.2. Advantages, Model Diversity and Technological Advances in Preclinical Imaging

5.3. Technological Progress and Ethical Benefits in Preclinical Imaging

5.4. Role of Artificial Intelligence in Preclinical PET and SPECT Imaging

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Aβ | Amyloid beta protein |

| APD | Avalanche photodiode |

| BGO | Bismuth germanate |

| CBF | Cerebral blood flow |

| CZT | Cadmium zinc telluride |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DOI | Depth of interaction |

| DTPA | Diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid |

| FBP | Filtered back-projection |

| FCH | Fluorocholine |

| FDG | Fluorodeoxyglucose |

| FLT | Fluorothymidine |

| FOV | Field of view |

| GFR | Glomerular filtration rate |

| GLUT | Glucose transporter |

| GTM | Geometric transfer matrix |

| HMPAO | Hexamethylpropyleneamine oxime |

| LGSO | Lutetium gadolinium oxyorthosilicate |

| LOR | Line of response |

| LSO | Lutetium oxyorthosilicate |

| LuYAP | Lutetium–yttrium aluminum perovskite |

| LYSO | Lutetium–yttrium oxyorthosilicate |

| MAG3 | Mercaptoacetyltriglycine |

| MDP | Methylene diphosphonate |

| MIBG | Metaiodobenzylguanidine |

| MIBI | Methoxyisobutylisonitrile |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| Na+/K+-ATPase | Sodium–potassium adenosine triphosphatase |

| NET | Norepinephrine transporter |

| OSEM | Ordered subsets expectation maximization |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| PET/CT | Integrated positron emission tomography and computed tomography system |

| PET/MR | Integrated positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance system |

| PET/SPECT/CT | Integrated positron emission tomography, single-photon emission computed tomography and computed tomography system |

| PIB | Pittsburgh compound B |

| PMT | Photomultiplier tube |

| PSF | Point spread function |

| PSMA | Prostate-specific membrane antigen |

| PVE | Partial volume effect |

| QC | Quality control |

| SNR | Signal-to-noise ratio |

| SPECT | Single-photon emission computed tomography |

| SPECT/CT | Integrated single-photon emission computed tomography and computed tomography system |

| SSTR | Somatostatin receptor |

| SSTR2 | Somatostatin receptor subtype 2 |

| TAC | Time–activity curve |

| TlCl | Thallium chloride |

| TOF | Time of flight |

References

- Curie, E. Madame Curie: A Biography; Grand Central Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Saenger, E.L.; Adamek, G.D. Marie Curie and nuclear medicine: Closure of a circle. Med. Phys. 1999, 26, 1761–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantis, A.; Magiorkinis, E.; Papadimitriou, A.; Androutsos, G. The contribution of Maria Sklodowska-Curie and Pierre Curie to Nuclear and Medical Physics. A hundred and ten years after the discovery of radium. Hell. J. Nucl. Med. 2008, 11, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- The Human Genome. Science genome map. Science 2001, 291, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lander, E.S.; Linton, L.M.; Birren, B.; Nusbaum, C.; Zody, M.C.; Baldwin, J.; Devon, K.; Dewar, K.; Doyle, M.; FitzHugh, W.; et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 2001, 409, 860–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendee, W.R.; Chien, S.; Maynard, C.D.; Dean, D.J. The National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering: History, Status, and Potential Impact. Radiology 2002, 222, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Systems and Methods for Small Animal Imaging (SBIR/STTR). Available online: http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-EB-03-002.html (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Junior, A.G. Non-genetic rats models for atherosclerosis research from past to present. Front. Biosci. 2019, 11, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, A.E.N.; de Queiroz, J.L.C.; Maciel, B.L.L.; de Araújo Morais, A.H. Experimental Models and Their Applicability in Inflammation Studies: Rodents, Fish, and Nematodes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakoff, D. The Rise of the Mouse, Biomedicine’s Model Mammal. Science (1979) 2000, 288, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilkenny, C.; Browne, W.J.; Cuthill, I.C.; Emerson, M.; Altman, D.G. Improving Bioscience Research Reporting: The ARRIVE Guidelines for Reporting Animal Research. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuccurullo, V.; Di Stasio, G.D.; Schillirò, M.L.; Mansi, L. Small-Animal Molecular Imaging for Preclinical Cancer Research: μPET and μSPECT. Curr. Radiopharm. 2016, 9, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.E.; Strong, R.; Sharp, Z.D.; Nelson, J.F.; Astle, C.M.; Flurkey, K.; Nadon, N.L.; Wilkinson, J.E.; Frenkel, K.; Carter, C.S.; et al. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature 2009, 460, 392–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, R.J.; Fagan, A.M.; Holtzman, D.M. Multimodal techniques for diagnosis and prognosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 2009, 461, 916–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, S.; Inal, J.M. Animal Models of Human Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summary Report on the Statistics on the Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes in the Member States of the European Union and Norway in 2018. Available online: https://www.understandinganimalresearch.org.uk/news/eu-wide-animals-in-research-statistics-for-2018-released (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- European Animal Research Association (EARA). Available online: https://www.eara.eu/ (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Raies, A.B.; Bajic, V.B. In silico toxicology: Computational methods for the prediction of chemical toxicity. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2016, 6, 147–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, M.L.; Gambhir, S.S. A Molecular Imaging Primer: Modalities, Imaging Agents, and Applications. Physiol. Rev. 2012, 92, 897–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiraga, Ł.; Kucharzewska, P.; Paisey, S.; Cheda, Ł.; Domańska, A.; Rogulski, Z.; Rygiel, T.P.; Boffi, A.; Król, M. Nuclear imaging for immune cell tracking in vivo—Comparison of various cell labeling methods and their application. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 445, 214008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, D.J.; Cherry, S.R. Small-Animal Preclinical Nuclear Medicine Instrumentation and Methodology. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2008, 38, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, K.; Flavell, R.; Wilson, D.M. Exploring Metabolism In Vivo Using Endogenous 11 C Metabolic Tracers. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2017, 47, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhaylongsod, F.G.; Lowe, V.J.; Patz, E.F.; Vaughn, A.L.; Coleman, R.E.; Wolfe, W.G. Detection of primary and recurrent lung cancer by means of F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET). J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1995, 110, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crișan, G.; Moldovean-Cioroianu, N.S.; Timaru, D.-G.; Andrieș, G.; Căinap, C.; Chiș, V. Radiopharmaceuticals for PET and SPECT Imaging: A Literature Review over the Last Decade. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, G.; Bruselli, L.; Kuwert, T.; Kim, E.E.; Flotats, A.; Israel, O.; Dondi, M.; Watanabe, N. A review on the clinical uses of SPECT/CT. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2010, 37, 1959–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertz, S. Radioactive Iodine in the Study of Thyroid Physiology. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1946, 131, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.; Domnanich, K.A.; Umbricht, C.A.; van der Meulen, N.P. Scandium and terbium radionuclides for radiotheranostics: Current state of development towards clinical application. Br. J. Radiol. 2018, 91, 20180074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.; Zhernosekov, K.; Köster, U.; Johnston, K.; Dorrer, H.; Hohn, A.; van der Walt, N.T.; Türler, A.; Schibli, R. A Unique Matched Quadruplet of Terbium Radioisotopes for PET and SPECT and for α- and β−Radionuclide Therapy: An In Vivo Proof-of-Concept Study with a New Receptor-Targeted Folate Derivative. J. Nucl. Med. 2012, 53, 1951–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Sagastume, E.A.; Lee, D.; McAlister, D.; DeGraffenreid, A.J.; Olewine, K.R.; Graves, S.; Copping, R.; Mirzadeh, S.; Zimmerman, B.E.; et al. 203/212Pb Theranostic Radiopharmaceuticals for Image-guided Radionuclide Therapy for Cancer. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 27, 7003–7031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Iorio, V.; Sarnelli, A.; Boschi, S.; Sansovini, M.; Genovese, R.M.; Stefanescu, C.; Ghizdovat, V.; Jalloul, W.; Young, J.; Sosabowski, J.; et al. Recommendations on the Clinical Application and Future Potential of α-Particle Therapy: A Comprehensive Review of the Results from the SECURE Project. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizvi, S.M.A.; Song, E.Y.; Raja, C.; Beretov, J.; Morgenstern, A.; Apostolidis, C.; Russell, P.J.; Kearsley, J.H.; Abbas, K.; Allen, B.J. Preparation and testing of bevacizumab radioimmunoconjugates with Bismuth-213 and Bismuth-205/Bismuth-206. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2008, 7, 1547–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellico, J.; Gawne, P.J.; de Rosales, R.T.M. Radiolabelling of nanomaterials for medical imaging and therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 3355–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, D.L.; Humm, J.L.; Todd-Pokropek, A.; van Aswegen, A. Available online: https://www-pub.iaea.org/MTCD/Publications/PDF/Pub1617web-1294055.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Moore, S.C.; Kouris, K.; Cullum, I. Collimator design for single photon emission tomography. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 1992, 19, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, H. (Ed.) Molecular Imaging of Small Animals; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Van Audenhaege, K.; Van Holen, R.; Vandenberghe, S.; Vanhove, C.; Metzler, S.D.; Moore, S.C. Review of SPECT collimator selection, optimization, and fabrication for clinical and preclinical imaging. Med. Phys. 2015, 42, 4796–4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambhir, S.S.; Czernin, J.; Schwimmer, J.; Silverman, D.H.; Coleman, R.E.; Phelps, M.E. A tabulated summary of the FDG PET literature. J. Nucl. Med. 2001, 42, S1–S93. [Google Scholar]

- Schöll, M.; Damián, A.; Engler, H. Fluorodeoxyglucose PET in Neurology and Psychiatry. PET Clin. 2014, 9, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fueger, B.J.; Czernin, J.; Hildebrandt, I.; Tran, C.; Halpern, B.S.; Stout, D.; Phelps, M.E.; Weber, W.A. Impact of animal handling on the results of 18F-FDG PET studies in mice. J. Nucl. Med. 2006, 47, 999–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, T.L.; Dence, C.S.; Engelbach, J.A.; Herrero, P.; Gropler, R.J.; Welch, M.J. Techniques necessary for multiple tracer quantitative small-animal imaging studies. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2005, 32, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meester, E.J.; Krenning, B.J.; de Swart, J.; Segbers, M.; Barrett, H.E.; Bernsen, M.R.; Van der Heiden, K.; de Jong, M. Perspectives on Small Animal Radionuclide Imaging; Considerations and Advances in Atherosclerosis. Front. Med. 2019, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.W.; Rakic, P. Three-dimensional counting: An accurate and direct method to estimate numbers of cells in sectioned material. J. Comp. Neurol. 1988, 278, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanekal, S.; Sahai, A.; Jones, R.E.; Brown, D. Storage-phosphor autoradiography: A rapid and highly sensitive method for spatial imaging and quantitation of radioisotopes. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 1995, 33, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcari, N.; Bisogni, M.G.; Del Guerra, A. Positron emission tomography: Its 65 years and beyond. La Riv. Del Nuovo C. 2024, 46, 693–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiewitz, O.; Hevesy, G. Radioactive Indicators in the Study of Phosphorus Metabolism in Rats. Nature 1935, 136, 754–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, W.G. Georg Charles de Hevesy: The father of nuclear medicine. J. Nucl. Med. 1979, 20, 590–594. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstadter, R. Alkali Halide Scintillation Counters. Phys. Rev. 1948, 74, 100–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanno, I.; Takahashi, M.; Yamaya, T. Michel M. Ter-Pogossian (1925–1996): A pioneer of positron emission tomography weighted in fast imaging and Oxygen-15 application. Radiol. Phys. Technol. 2020, 13, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radon, J. Über die Bestimmung von Funktionen durch ihre Integralwerte längs gewisser Mannigfaltigkeiten. Ber. Sächs. Akad. Wiss. Leipz. 1917, 69, 262–277. [Google Scholar]

- Goertzen, A.L.; Bao, Q.; Bergeron, M.; Blankemeyer, E.; Blinder, S.; Cañadas, M.; Chatziioannou, A.F.; Dinelle, K.; Elhami, E.; Jans, H.-S.; et al. NEMA NU 4-2008 Comparison of Preclinical PET Imaging Systems. J. Nucl. Med. 2012, 53, 1300–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, C.S.; Zaidi, H. Current Trends in Preclinical PET System Design. PET Clin. 2007, 2, 125–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatziioannou, A. PET Scanners Dedicated to Molecular Imaging of Small Animal Models. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2002, 4, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeswaran, S.; Bailey, D.L.; Hume, S.P.; Townsend, D.W.; Geissbuhler, A.; Young, J.; Jones, T. 2D and 3D imaging of small animals and the human radial artery with a high resolution detector for PET. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 1992, 11, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirrashedi, M.; Zaidi, H.; Ay, M.R. Advances in Preclinical PET Instrumentation. PET Clin. 2020, 15, 403–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomfield, P.M.; Rajeswaran, S.; Spinks, T.J.; Hume, S.P.; Myers, R.; Ashworth, S.; Clifford, K.M.; Jones, W.F.; Byars, L.G.; Young, J.; et al. The design and physical characteristics of a small animal positron emission tomograph. Phys. Med. Biol. 1995, 40, 1105–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoess, C.; Siegel, S.; Smith, A.; Newport, D.; Richerzhagen, N.; Winkeler, A.; Jacobs, A.; Goble, R.N.; Graf, R.; Wienhard, K.; et al. Performance evaluation of the microPET R4 PET scanner for rodents. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2003, 30, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Guerra, A.; Di Domenico, G.; Scandola, M.; Zavattini, G. High spatial resolution small animal YAP-PET. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 1998, 409, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcari, N.; Del Guerra, A.; Bartoli, A.; Bianchi, D.; Lazzarotti, M.; Sensi, L.; Menichetti, L.; Lecchi, M.; Erba, P.A.; Mariani, G.; et al. Evaluation of the performance of the YAP-(S)PET scanner and its application in neuroscience. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 2007, 571, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, M.C.; Reder, S.; Weber, A.W.; Ziegler, S.I.; Schwaiger, M. Performance evaluation of the Philips MOSAIC small animal PET scanner. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2007, 34, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sempere Roldan, P.; Chereul, E.; Dietzel, O.; Magnier, L.; Pautrot, C.; Rbah, L.; Sappey-Marinier, D.; Wagner, A.; Zimmer, L.; Janier, M.; et al. Raytest ClearPETTM, a new generation small animal PET scanner. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 2007, 571, 498–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.; Ratib, O.; Zaidi, H. Performance Evaluation of the FLEX Triumph X-PET Scanner Using the National Electrical Manufacturers Association NU-4 Standards. J. Nucl. Med. 2010, 51, 1608–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergeron, M.; Cadorette, J.; Bureau-Oxton, C.; Beaudoin, J.-F.; Tetrault, M.-A.; Leroux, J.-D.; Lepage, M.D.; Robert, G.; Fontaine, R.; Lecomte, R. Performance evaluation of the LabPET12, a large axial FOV APD-based digital PET scanner. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium Conference Record (NSS/MIC), Orlando, FL, USA, 25–31 October 2009; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 4017–4021. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, R.; Ratib, O.; Zaidi, H. NEMA NU-04-based performance characteristics of the LabPET-8TM small animal PET scanner. Phys. Med. Biol. 2011, 56, 6649–6664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, M.; Cadorette, J.; Beaudoin, J.-F.; Lepage, M.D.; Robert, G.; Selivanov, V.; Tetrault, M.-A.; Viscogliosi, N.; Norenberg, J.P.; Fontaine, R.; et al. Performance Evaluation of the LabPET APD-Based Digital PET Scanner. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2009, 56, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolli, O.; Eleftheriou, A.; Cecchetti, M.; Camarlinghi, N.; Belcari, N.; Tsoumpas, C. PET iterative reconstruction incorporating an efficient positron range correction method. Phys. Medica 2016, 32, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emond, E.C.; Groves, A.M.; Hutton, B.F.; Thielemans, K. Effect of positron range on PET quantification in diseased and normal lungs. Phys. Med. Biol. 2019, 64, 205010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, C.S.; Hoffman, E.J. Calculation of positron range and its effect on the fundamental limit of positron emission tomography system spatial resolution. Phys. Med. Biol. 1999, 44, 781–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, M.; Loignon-Houle, F.; Auger, É.; Lapointe, G.; Dussault, J.-P.; Lecomte, R. On the implementation of acollinearity in PET Monte Carlo simulations. Phys. Med. Biol. 2024, 69, 18NT01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, G.C.d.A.; Gontijo, R.M.G.; da Silva, J.B.; Mamede, M.; Ferreira, A.V. Spatial resolution of a preclinical PET tomograph. Braz. J. Radiat. Sci. 2021, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ali, H.H.; Bodholdt, R.P.; Jørgensen, J.T.; Myschetzky, R.; Kjaer, A. Importance of Attenuation Correction (AC) for Small Animal PET Imaging. Diagnostics 2012, 2, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.; Zaidi, H. Scatter Characterization and Correction for Simultaneous Multiple Small-Animal PET Imaging. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2014, 16, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, P.L.; Stout, D.B.; Komisopoulou, E.; Chatziioannou, A.F. A method of image registration for small animal, multi-modality imaging. Phys. Med. Biol. 2006, 51, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandervoort, E.; Camborde, M.-L.; Jan, S.; Sossi, V. Monte Carlo modelling of singles-mode transmission data for small animal PET scanners. Phys. Med. Biol. 2007, 52, 3169–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, E.; Irazola, L.; Collantes, M.; Ecay, M.; Cuenca, T.; Martí-Climent, J.M.; Peñuelas, I. Performance evaluation of a preclinical SPECT/CT system for multi-animal and multi-isotope quantitative experiments. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, H.; Willowson, K.P.; Bailey, D.L. Partial volume effect in SPECT & PET imaging and impact on radionuclide dosimetry estimates. Asia Ocean. J. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2023, 11, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franc, B.L.; Acton, P.D.; Mari, C.; Hasegawa, B.H. Small-Animal SPECT and SPECT/CT: Important Tools for Preclinical Investigation. J. Nucl. Med. 2008, 49, 1651–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, D.A.; Ivanovic, M.; Franceschi, D.; Strand, S.E.; Erlandsson, K.; Franceschi, M.; Atkins, H.L.; Coderre, J.A.; Susskind, H.; Button, T. Pinhole SPECT: An approach to in vivo high resolution SPECT imaging in small laboratory animals. J. Nucl. Med. 1994, 35, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vastenhouw, B.; Beekman, F. Submillimeter total-body murine imaging with U-SPECT-I. J. Nucl. Med. 2007, 48, 487–493. [Google Scholar]

- Nuyts, J.; Vunckx, K.; Defrise, M.; Vanhove, C. Small animal imaging with multi-pinhole SPECT. Methods 2009, 48, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, A.B.; Franc, B.L.; Gullberg, G.T.; Hasegawa, B.H. Assessment of the sources of error affecting the quantitative accuracy of SPECT imaging in small animals. Phys. Med. Biol. 2008, 53, 2233–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seret, A.; Nguyen, D.; Bernard, C. Quantitative capabilities of four state-of-the-art SPECT-CT cameras. EJNMMI Res. 2012, 2, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, D.P.; MacDonald, L.R.; Beekman, F.J.; Yuchuan Wang Patt, B.E.; Iwanczyk, J.S.; Tsui, B.M.W.; Hoffman, E.J. Performance evaluation of A-SPECT: A high resolution desktop pinhole SPECT system for imaging small animals. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2002, 49, 2139–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, B.-K.; Seo, Y.; Bacharach, S.L.; Carrasquillo, J.A.; Libutti, S.K.; Shukla, H.; Hasegawa, B.H.; Hawkins, R.A.; Franc, B.L. Partial-volume correction in PET: Validation of an iterative postreconstruction method with phantom and patient data. J. Nucl. Med. 2007, 48, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chang, L.-T. A Method for Attenuation Correction in Radionuclide Computed Tomography. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 1978, 25, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerdekoohi, S.K.; Vosoughi, N.; Tanha, K.; Assadi, M.; Ghafarian, P.; Rahmim, A.; Ay, M.R. Implementation of absolute quantification in small-animal SPECT imaging: Phantom and animal studies. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2017, 18, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, B.F.; Buvat, I.; Beekman, F.J. Review and current status of SPECT scatter correction. Phys. Med. Biol. 2011, 56, R85–R112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, M.S.; Rahmim, A.; Arabi, H.; Sanaat, A.; Zeraatkar, N.; Bouchareb, Y.; Liu, C.; Alavi, A.; King, M.; Boellaard, R.; et al. Critical review of partial volume correction methods in PET and SPECT imaging: Benefits, pitfalls, challenges, and future outlook. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouchareb, Y.; AlSaadi, A.; Zabah, J.; Jain, A.; Al-Jabri, A.; Phiri, P.; Shi, J.Q.; Delanerolle, G.; Sirasanagandla, S.R. Technological Advances in SPECT and SPECT/CT Imaging. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.; Wong, K.H.; Sun, M.; Franc, B.L.; Hawkins, R.A.; Hasegawa, B.H. Correction of photon attenuation and collimator response for a body-contouring SPECT/CT imaging system. J. Nucl. Med. 2005, 46, 868–877. [Google Scholar]

- Kastis, G.A.; Furenlid, L.R.; Wilson, D.W.; Peterson, T.E.; Barber, H.B.; Barrett, H.H. Compact CT/SPECT Small-Animal Imaging System. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2004, 51, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Li, X.; Xu, L.; Kuang, Y. PET/SPECT/spectral-CT/CBCT imaging in a small-animal radiation therapy platform: A Monte Carlo study—Part I: Quad-modal imaging. Med. Phys. 2024, 51, 2941–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wang, H.; Xu, L.; Kuang, Y. PET/SPECT/Spectral-CT/CBCT imaging in a small-animal radiation therapy platform: A Monte Carlo study—Part II: Biologically guided radiotherapy. Med. Phys. 2024, 51, 3619–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, H.A. The August Krogh principle: “For many problems there is an animal on which it can be most conveniently studied”. J. Exp. Zool. 1975, 194, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namati, E.; Thiesse, J.; Sieren, J.C.; Ross, A.; Hoffman, E.A.; McLennan, G. Longitudinal assessment of lung cancer progression in the mouse using in vivo micro-CT imaging. Med. Phys. 2010, 37, 4793–4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannheim, J.G.; Kara, F.; Doorduin, J.; Fuchs, K.; Reischl, G.; Liang, S.; Verhoye, M.; Gremse, F.; Mezzanotte, L.; Huisman, M.C. Standardization of Small Animal Imaging—Current Status and Future Prospects. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2018, 20, 716–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, W.M.S.; Burch, R.L. The Principles of Humane Experimental Technique; Methuen: London, UK, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Kiessling, F.; Pichler, B.J.; Hauff, P. Small Animal Imaging: Basics and Practical Guide; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, P.; Roy, S.; Ghosh, D.; Nandi, S.K. Role of animal models in biomedical research: A review. Lab. Anim. Res. 2022, 38, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, N.T.; Demas, G.E. Neuroendocrine-immune circuits, phenotypes, and interactions. Horm. Behav. 2017, 87, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, R.J.; Shani, M. Are animal models as good as we think? Theriogenology 2008, 69, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jong, M.; Essers, J.; van Weerden, W.M. Imaging preclinical tumour models: Improving translational power. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissleder, R. Scaling down imaging: Molecular mapping of cancer in mice. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriga-Rivera, A.; Tatarinoff, V.; Lovell, N.H.; Morley, J.W.; Suaning, G.J. Long-term anesthetic protocol in rats: Feasibility in electrophysiology studies in visual prosthesis. Vet. Ophthalmol. 2018, 21, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festing, M.F.W. Inbred Strains Should Replace Outbred Stocks in Toxicology, Safety Testing, and Drug Development. Toxicol. Pathol. 2010, 38, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.G.; Tashima, H.; Wakizaka, H.; Nishikido, F.; Higuchi, M.; Takahashi, M.; Yamaya, T. Submillimeter-Resolution PET for High-Sensitivity Mouse Brain Imaging. J. Nucl. Med. 2023, 64, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magota, K.; Kubo, N.; Kuge, Y.; Nishijima, K.; Zhao, S.; Tamaki, N. Performance characterization of the Inveon preclinical small-animal PET/SPECT/CT system for multimodality imaging. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2011, 38, 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, L.; Horvath, I.; Ferreira, S.; Lemos, J.; Costa, P.; Vieira, D.; Veres, D.S.; Szigeti, K.; Summavielle, T.; Máthé, D.; et al. Preclinical Imaging: An Essential Ally in Modern Biosciences. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2014, 18, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhove, C.; Koole, M.; Fragoso Costa, P.; Schottelius, M.; Mannheim, J.; Kuntner, C.; Warnock, G.; McDougald, W.; Tavares, A.; Bernsen, M. Preclinical SPECT and PET: Joint EANM and ESMI procedure guideline for implementing an efficient quality control programme. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2024, 51, 3822–3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougald, W.A.; Mannheim, J.G. Understanding the importance of quality control and quality assurance in preclinical PET/CT imaging. EJNMMI Phys. 2022, 9, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Z.; Xi, P.; Zheng, D.; Xie, Z.; Meng, X.; Ren, Q. The Impact of PET Imaging on Translational Medicine: Insights from Large-Animal Disease Models. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goutal, S.; Tournier, N.; Guillermier, M.; Van Camp, N.; Barret, O.; Gaudin, M.; Bottlaender, M.; Hantraye, P.; Lavisse, S. Comparative test-retest variability of outcome parameters derived from brain [18F]FDG PET studies in non-human primates. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.; Collins, R.; Denvir, M.A.; McDougald, W.A. PET/CT Technology in Adult Zebrafish: A Pilot Study Toward Live Longitudinal Imaging. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 725548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, K.; Clark, M.D.; Torroja, C.F.; Torrance, J.; Berthelot, C.; Muffato, M.; Collins, J.E.; Humphray, S.; McLaren, K.; Matthews, L.; et al. The zebrafish reference genome sequence and its relationship to the human genome. Nature 2013, 496, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvolský, M.; Schaar, M.; Seeger, S.; Rakers, S.; Rafecas, M. Development of a digital zebrafish phantom and its application to dedicated small-fish PET. Phys. Med. Biol. 2022, 67, 175005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marciano, S.; Ionescu, T.M.; Saw, R.S.; Cheong, R.Y.; Kirik, D.; Maurer, A.; Pichler, B.J.; Herfert, K. Combining CRISPR-Cas9 and brain imaging to study the link from genes to molecules to networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2122552119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hevesy, G. The Absorption and Translocation of Lead by Plants. Biochem. J. 1923, 17, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Radiopharmaceutical | Application | Parameter | PET | SPECT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [18F]FDG | Oncology, inflammation, neurology | Glucose uptake; GLUT; glycolysis | ✓ | |

| [18F]FCH/[11C]Choline | Prostate cancer | Membrane turnover | ✓ | |

| [18F]FLT | Proliferation | DNA synthesis | ✓ | |

| [68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE | Neuroendocrine tumors | SSTR2 density | ✓ | |

| [68Ga]Ga-PSMA-11 | Prostate cancer | PSMA expression | ✓ | |

| [18F]NaF | Bone metastases | Osteoblastic activity | ✓ | |

| [11C]PIB | Alzheimer’s disease | Aβ | ✓ | |

| [99mTc]MDP | Bone imaging | Osteoblastic turnover | ✓ | |

| [99mTc]MIBI | Cardiac perfusion | Mitochondrial potential | ✓ | |

| [201Tl]TlCl | Myocardial perfusion | Na+/K+-ATPase | ✓ | |

| [123I]MIBG | Neuroblastoma | NET uptake | ✓ | |

| [111In]Octreotide | Neuroendocrine tumors | SSTR | ✓ | |

| [99mTc]HMPAO | Brain perfusion | CBF | ✓ | |

| [99mTc]MAG3 | Renal imaging | Tubular secretion | ✓ | |

| [99mTc]DTPA | Renal filtration | GFR | ✓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bruzgo-Grzybko, M.; Kalita, I.S.; Olichwier, A.J.; Bielicka, N.; Chabielska, E.; Gromotowicz-Poplawska, A. Preclinical PET and SPECT Imaging in Small Animals: Technologies, Challenges and Translational Impact. Cells 2026, 15, 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010073

Bruzgo-Grzybko M, Kalita IS, Olichwier AJ, Bielicka N, Chabielska E, Gromotowicz-Poplawska A. Preclinical PET and SPECT Imaging in Small Animals: Technologies, Challenges and Translational Impact. Cells. 2026; 15(1):73. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010073

Chicago/Turabian StyleBruzgo-Grzybko, Magdalena, Izabela Suwda Kalita, Adam Jan Olichwier, Natalia Bielicka, Ewa Chabielska, and Anna Gromotowicz-Poplawska. 2026. "Preclinical PET and SPECT Imaging in Small Animals: Technologies, Challenges and Translational Impact" Cells 15, no. 1: 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010073

APA StyleBruzgo-Grzybko, M., Kalita, I. S., Olichwier, A. J., Bielicka, N., Chabielska, E., & Gromotowicz-Poplawska, A. (2026). Preclinical PET and SPECT Imaging in Small Animals: Technologies, Challenges and Translational Impact. Cells, 15(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010073