An Exceptionally Complex Chromosome Rearrangement in the Great Tit (Parus major): Genetic Composition, Meiotic Behavior and Population Frequency

Highlights

- A complex rearrangement on chromosome 1A, combining a ~55 Mb inversion and >30 Mb of copy-number expansion, is present in ~19% of the great tits in the Siberian population. A similar rearrangement has been previously detected in 5% of birds in the European population.

- The amplified region includes a sequence homologous to the FAM118A locus conserved in vertebrates with a nested 630 bp tandem repeat, expanded to ~50,000 copies in the rearranged chromosome.

- The rearranged chromosome provides a natural system to investigate the genomic consequences and evolutionary maintenance of large inversion–amplification complexes.

- The FAM118A expansion provides a framework for assessing potential functional and adaptive effects of extreme gene amplification in a wild population.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Fibroblast Cell Cultures and Mitotic Metaphase Chromosomes

2.3. C-Banding, Synaptonemal Complex (SC) Spreading, and Immunostaining

2.4. Chromosome Measurements and Recombination Maps

2.5. Hybridization Probes and FISH

2.6. Microscopic Analysis

2.7. Library Preparation and Sequencing

2.8. Hi-C Contact Map Construction

2.9. CNV Analysis

2.10. Reconstruction and Analysis of the FAM118A-Homologous Locus

2.11. Population Frequency Estimates and Statistical Analyses

3. Results

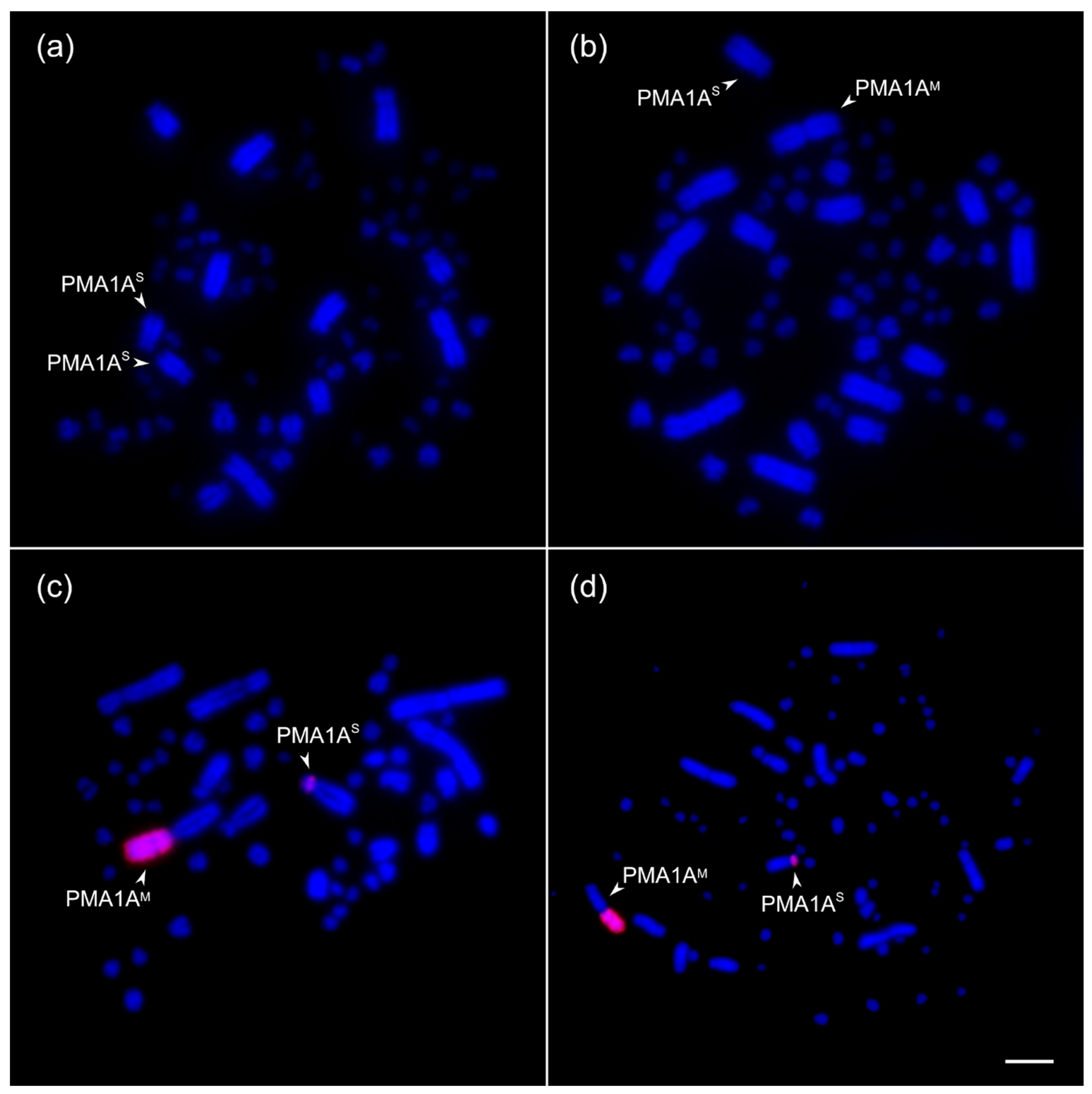

3.1. Mitotic Chromosome Analysis Reveals PMA1A Heteromorphism in Natural Populations of the Great Tit

3.2. The Rearranged Chromosome Is Present in a Low Frequency in the Siberian Population

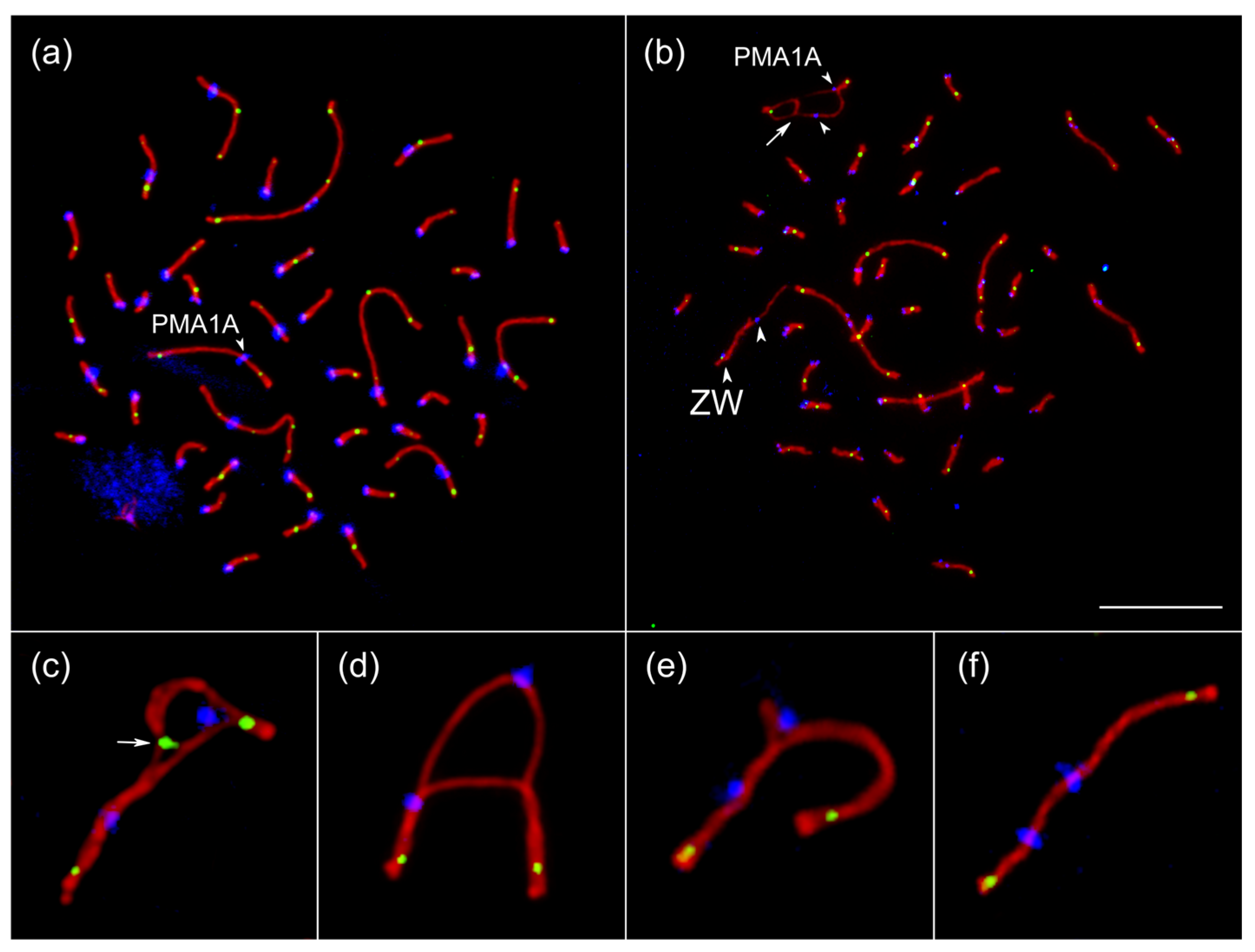

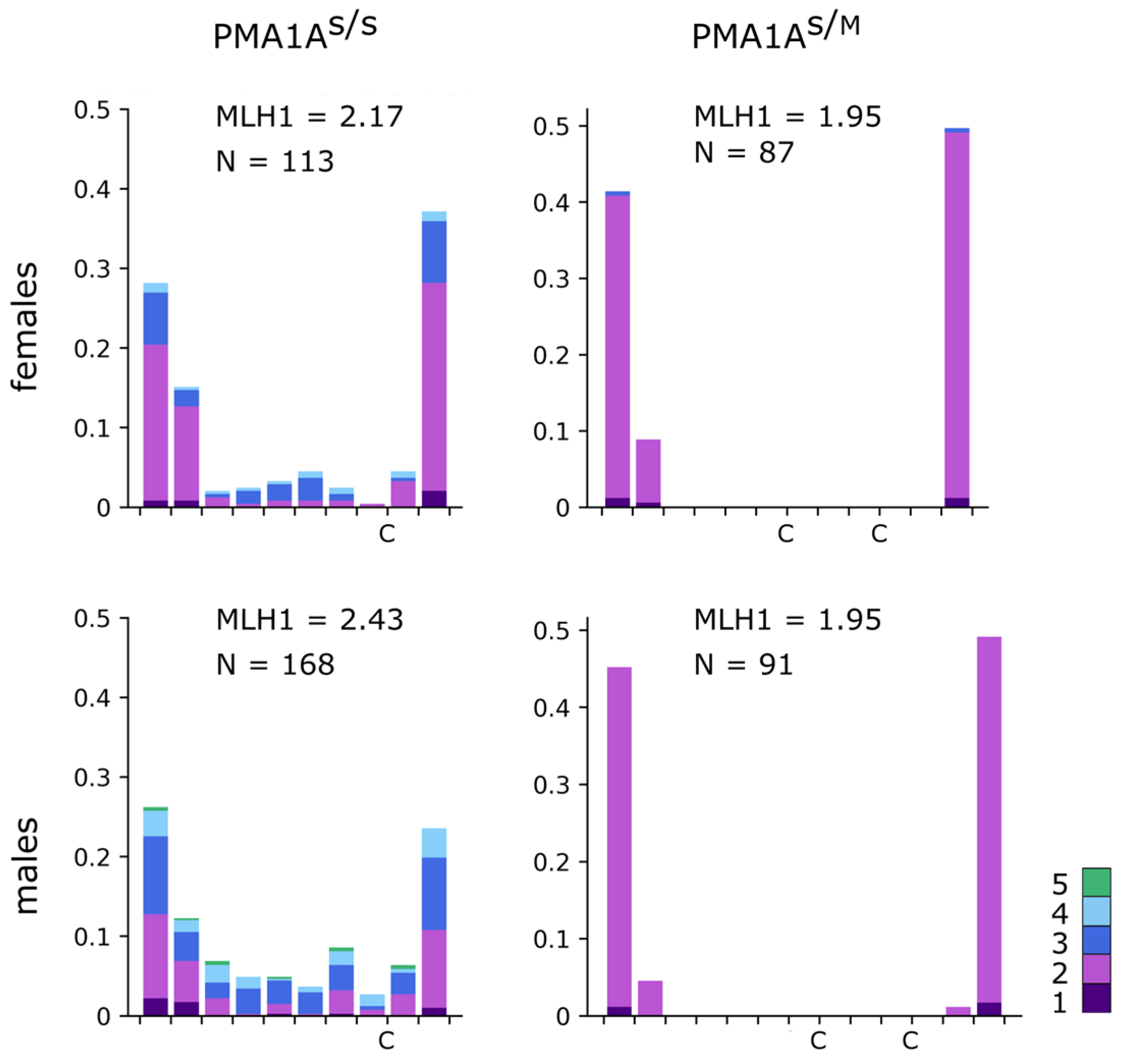

3.3. Chromosome Synapsis and Recombination Patterns Indicate Inversion and Additional Genetic Material in PMA1AM

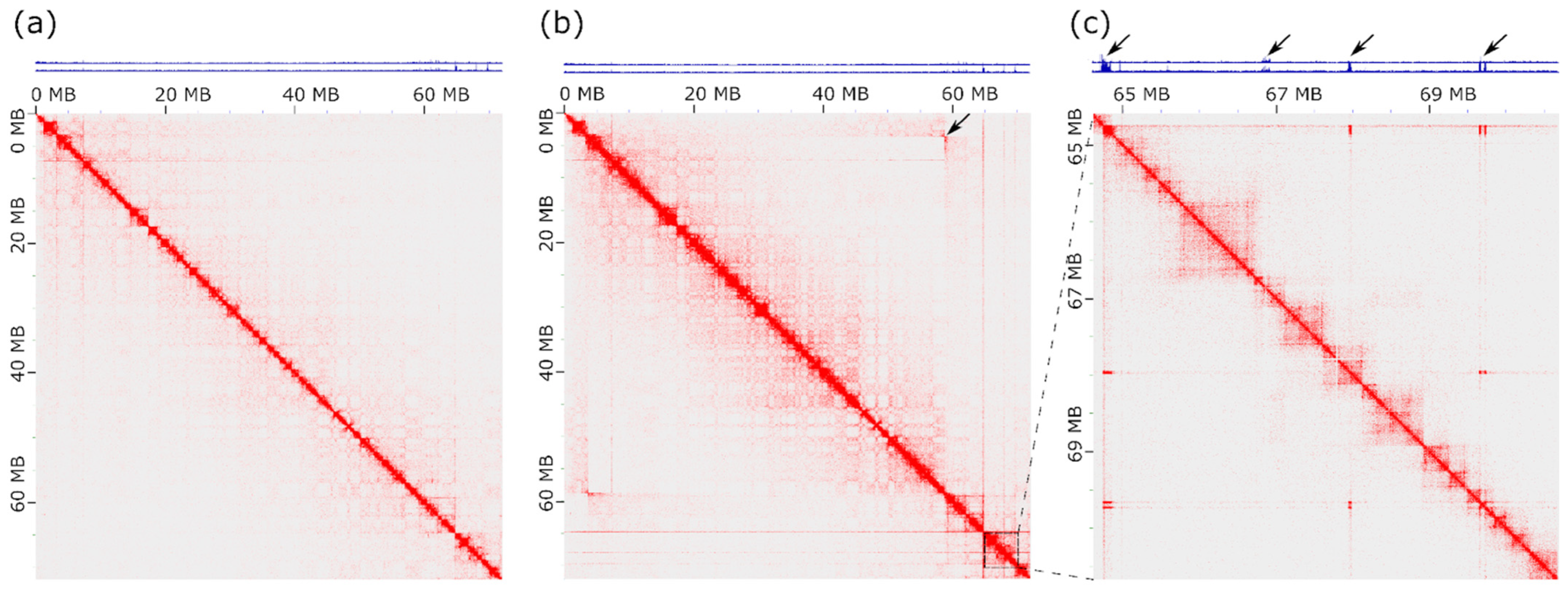

3.4. Hi-C Analysis Defines the Boundaries of the Inversion in PMA1AM

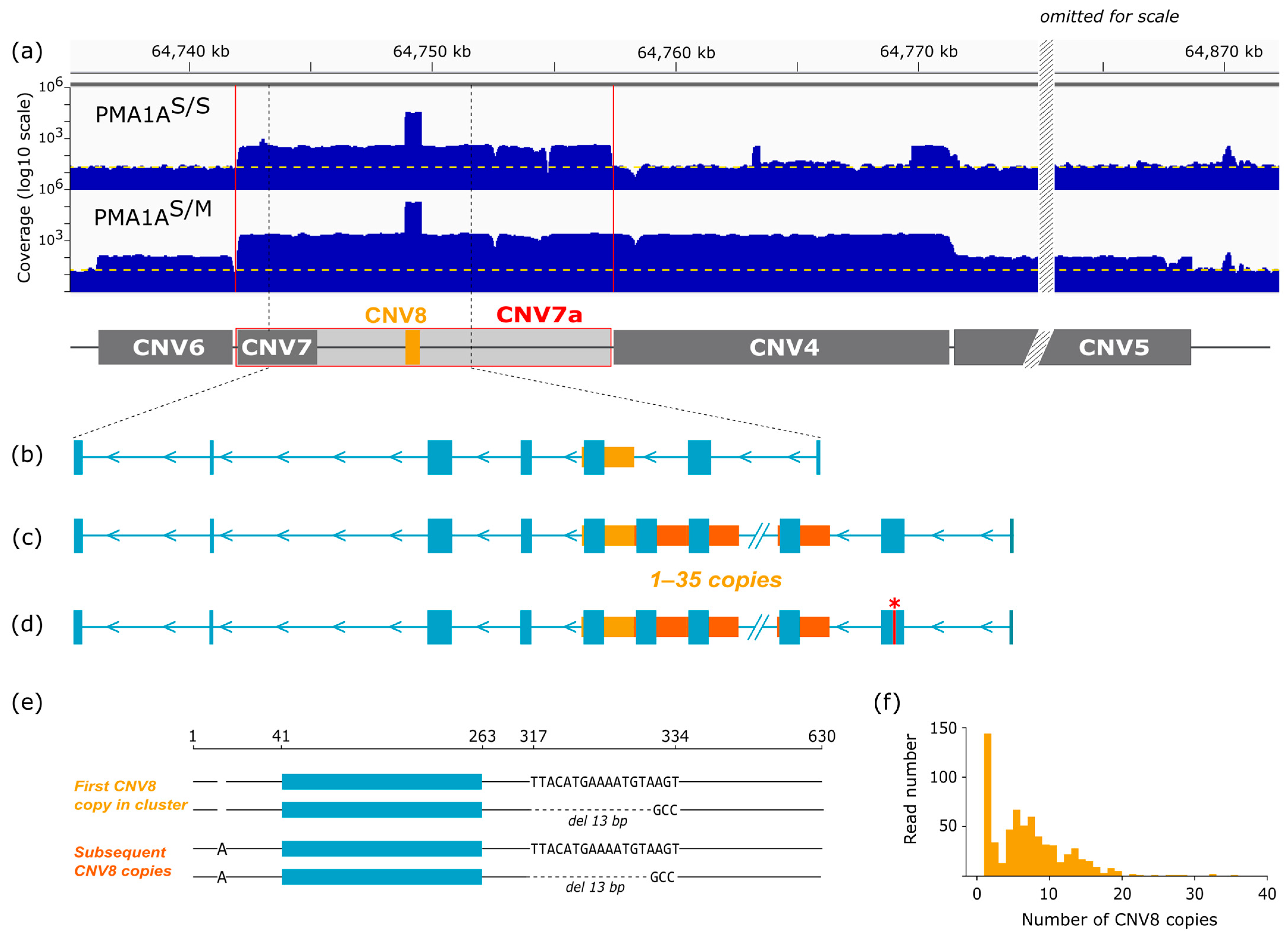

3.5. CNV Analysis Reveals Extensive Amplification of a Short Repetitive Sequence

3.6. Long-Read Analysis Identifies Large-Scale Amplification of the FAM118A Locus

3.7. Siberian and European Great Tits Share a Complex Rearrangement in PMA1A

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moses, M.J.; Poorman, P.A.; Roderick, T.H.; Davisson, M.T. Synaptonemal Complex Analysis of Mouse Chromosomal Rearrangements. Chromosoma 1982, 84, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, E.; Blanco, J.; Vidal, F. Recombination in Heterozygote Inversion Carriers. Hum. Reprod. 2007, 22, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgasheva, A.A.; Borodin, P.M. Synapsis and Recombination in Inversion Heterozygotes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2010, 38, 1676–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellenreuther, M.; Bernatchez, L. Eco-Evolutionary Genomics of Chromosomal Inversions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2018, 33, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, M. How and Why Chromosome Inversions Evolve. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, B.M.; Griffin, D.K. Intrachromosomal Rearrangements in Avian Genome Evolution: Evidence for Regions Prone to Breakpoints. Heredity 2012, 108, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knief, U.; Müller, I.A.; Stryjewski, K.F.; Metzler, D.; Sorenson, M.D.; Wolf, J.B.W. Evolution of Chromosomal Inversions Across an Avian Radiation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41, msae092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, D.M.; Price, T.D. Chromosomal Inversion Differences Correlate with Range Overlap in Passerine Birds. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1, 1526–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, L.Y.; Maney, D.L.; Thomas, J.W. Chromosome-Wide Linkage Disequilibrium Caused by an Inversion Polymorphism in the White-Throated Sparrow (Zonotrichia albicollis). Heredity 2011, 106, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Küpper, C.; Stocks, M.; Risse, J.E.; Dos Remedios, N.; Farrell, L.L.; McRae, S.B.; Morgan, T.C.; Karlionova, N.; Pinchuk, P.; Verkuil, Y.I.; et al. A Supergene Determines Highly Divergent Male Reproductive Morphs in the Ruff. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundberg, M.; Åkesson, S.; Bensch, S. Characterization of a Divergent Chromosome Region in the Willow Warbler Phylloscopus Trochilus Using Avian Genomic Resources. J. Evol. Biol. 2011, 24, 1241–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knief, U.; Hemmrich-Stanisak, G.; Wittig, M.; Franke, A.; Griffith, S.C.; Kempenaers, B.; Forstmeier, W. Fitness Consequences of Polymorphic Inversions in the Zebra Finch Genome. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.; Forstmeier, W.; Suh, A.; Bambach, L.; Borges, I.; Low, G.W.; Dion-Côté, A.-M.; Knief, U.; Wolf, J.; Kempenaers, B. Evolution of Large Polymorphic Inversions in a Panmictic Songbird. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2025, 42, msaf262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Zhang, F.; Lupski, J.R. Mechanisms for Human Genomic Rearrangements. Pathogenetics 2008, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, R.L.; Brand, H.; Redin, C.E.; Hanscom, C.; Antolik, C.; Stone, M.R.; Glessner, J.T.; Mason, T.; Pregno, G.; Dorrani, N.; et al. Defining the Diverse Spectrum of Inversions, Complex Structural Variation, and Chromothripsis in the Morbid Human Genome. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollger, M.R.; Guitart, X.; Dishuck, P.C.; Mercuri, L.; Harvey, W.T.; Gershman, A.; Diekhans, M.; Sulovari, A.; Munson, K.M.; Lewis, A.P.; et al. Segmental Duplications and Their Variation in a Complete Human Genome. Science 2022, 376, eabj6965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, M.L.; Tan, F.J.; Lai, D.C.; Celniker, S.E.; Hoskins, R.A.; Dunham, M.J.; Zheng, Y.; Koshland, D. Competitive Repair by Naturally Dispersed Repetitive DNA During Non-Allelic Homologous Recombination. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1001228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, C.M.B.; Lupski, J.R. Mechanisms Underlying Structural Variant Formation in Genomic Disorders. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 17, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, B.J.; Dunham, M.J.; Raghuraman, M.K. A Unifying Model That Explains the Origins of Human Inverted Copy Number Variants. PLoS Genet. 2024, 20, e1011091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zody, M.C.; Jiang, Z.; Fung, H.-C.; Antonacci, F.; Hillier, L.W.; Cardone, M.F.; Graves, T.A.; Kidd, J.M.; Cheng, Z.; Abouelleil, A.; et al. Evolutionary Toggling of the MAPT 17q21.31 Inversion Region. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 1076–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porubsky, D.; Sanders, A.D.; Höps, W.; Hsieh, P.; Sulovari, A.; Li, R.; Mercuri, L.; Sorensen, M.; Murali, S.C.; Gordon, D.; et al. Recurrent Inversion Toggling and Great Ape Genome Evolution. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanciano, S.; Cristofari, G. Flip-Flop Genomics: Charting Inversions in the Human Population. Cell 2022, 185, 1811–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuy, J.; Grochowski, C.M.; Carvalho, C.M.B.; Lindstrand, A. Complex Genomic Rearrangements: An Underestimated Cause of Rare Diseases. Trends Genet. 2022, 38, 1134–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloissnig, S.; Pani, S.; Ebler, J.; Hain, C.; Tsapalou, V.; Söylev, A.; Hüther, P.; Ashraf, H.; Prodanov, T.; Asparuhova, M.; et al. Structural Variation in 1,019 Diverse Humans Based on Long-Read Sequencing. Nature 2025, 644, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innan, H.; Kondrashov, F. The Evolution of Gene Duplications: Classifying and Distinguishing Between Models. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010, 11, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, K.T.; Cuff, L.E.; Neidle, E.L. Copy Number Change: Evolving Views on Gene Amplification. Future Microbiol. 2013, 8, 887–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Evolution by Gene Duplication: An Update. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2003, 18, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrichsen, C.N.; Vinckenbosch, N.; Zöllner, S.; Chaignat, E.; Pradervand, S.; Schütz, F.; Ruedi, M.; Kaessmann, H.; Reymond, A. Segmental Copy Number Variation Shapes Tissue Transcriptomes. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondrashov, F.A. Gene Duplication as a Mechanism of Genomic Adaptation to a Changing Environment. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2012, 279, 5048–5057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Völker, M.; Backström, N.; Skinner, B.M.; Langley, E.J.; Bunzey, S.K.; Ellegren, H.; Griffin, D.K. Copy Number Variation, Chromosome Rearrangement, and Their Association with Recombination During Avian Evolution. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Li, C.; Li, Q.; Li, B.; Larkin, D.M.; Lee, C.; Storz, J.F.; Antunes, A.; Greenwold, J.; Meredith, R.W.; et al. Comparative Genomics Reveals Insights into Avian Genome Evolution and Adaptation. Science 2014, 346, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minias, P.; Pikus, E.; Whittingham, L.A.; Dunn, P.O. Evolution of Copy Number at the MHC Varies Across the Avian Tree of Life. Genome Biol. Evol. 2019, 11, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minias, P.; Whittingham, L.A.; Dunn, P.O. Coloniality and Migration are Related to Selection on MHC Genes in Birds. Evolution 2017, 71, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minias, P.; He, K.; Dunn, P.O. The Strength of Selection is Consistent Across Both Domains of the MHC Class I Peptide-Binding Groove in Birds. BMC Ecol. Evol. 2021, 21, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, V.N.; Gossmann, T.I.; Schachtschneider, K.M.; Garroway, C.J.; Madsen, O.; Verhoeven, K.J.F.; de Jager, V.; Megens, H.-J.; Warren, W.C.; Minx, P.; et al. Evolutionary Signals of Selection on Cognition from the Great Tit Genome and Methylome. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nussey, D.H.; Postma, E.; Gienapp, P.; Visser, M.E. Selection on Heritable Phenotypic Plasticity in a Wild Bird Population. Science 2005, 310, 304–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charmantier, A.; McCleery, R.H.; Cole, L.R.; Perrins, C.; Kruuk, L.E.B.; Sheldon, B.C. Adaptive Phenotypic Plasticity in Response to Climate Change in a Wild Bird Population. Science 2008, 320, 800–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stonehouse, J.C.; Spurgin, L.G.; Laine, V.N.; Bosse, M.; Great Tit HapMap Consortium; Groenen, M.A.M.; van Oers, K.; Sheldon, B.C.; Visser, M.E.; Slate, J. The Genomics of Adaptation to Climate in European Great Tit (Parus major) Populations. Evol. Lett. 2024, 8, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosse, M.; Spurgin, L.G.; Laine, V.N.; Cole, E.F.; Firth, J.A.; Gienapp, P.; Gosler, A.G.; McMahon, K.; Poissant, J.; Verhagen, I.; et al. Recent Natural Selection Causes Adaptive Evolution of an Avian Polygenic Trait. Science 2017, 358, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, V.H.; Laine, V.N.; Bosse, M.; Spurgin, L.G.; Derks, M.F.L.; van Oers, K.; Dibbits, B.; Slate, J.; Crooijmans, R.P.M.A.; Visser, M.E.; et al. The Genomic Complexity of a Large Inversion in Great Tits. Genome Biol. Evol. 2019, 11, 1870–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pristyazhnyuk, I.E.; Malinovskaya, L.P.; Borodin, P.M. Establishment of the Primary Avian Gonadal Somatic Cell Lines for Cytogenetic Studies. Animals 2022, 12, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, R.; Barragan, M.J.L.; Bullejos, M.; Marchal, J.A.; Diaz De La Guardia, R.; Sanchez, A. New C-Band Protocol by Heat Denaturation in the Presence of Formamide. Hereditas 2002, 137, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, A.H.F.M.; Plug, A.W.; Van Vugt, M.J.; De Boer, P. A Drying-Down Technique for the Spreading of Mammalian Meiocytes from the Male and Female Germline. Chromosome Res. 1997, 5, 66–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, L.K.; Reeves, A.; Webb, L.M.; Ashley, T. Distribution of Crossing over on Mouse Synaptonemal Complexes Using Immunofluorescent Localization of MLH1 protein. Genetics 1999, 151, 1569–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, A. MicroMeasure: A New Computer Program for the Collection and Analysis of Cytogenetic Data. Génome 2001, 44, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BACPAC Genomics. CHORI-261: Chicken BAC Library; BACPAC Genomics: Emeryville, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J.; Coulouris, G.; Zaretskaya, I.; Cutcutache, I.; Rozen, S.; Madden, T.L. Primer-BLAST: A Tool to Design Target-Specific Primers for Polymerase Chain Reaction. BMC Bioinform. 2012, 13, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liehr, T.; Kreskowski, K.; Ziegler, M.; Piaszinski, K.; Rittscher, K. The Standard FISH Procedure. In Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization (FISH): Application Guide; Liehr, T., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 109–118. ISBN 978-3-662-52959-1. [Google Scholar]

- Belaghzal, H.; Dekker, J.; Gibcus, J.H. Hi-C 2.0: An Optimized Hi-C Procedure for High-Resolution Genome-Wide Mapping of Chromosome Conformation. Methods 2017, 123, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, N.C.; Shamim, M.S.; Machol, I.; Rao, S.S.P.; Huntley, M.H.; Lander, E.S.; Aiden, E.L. Juicer Provides a One-Click System for Analyzing Loop-Resolution Hi-C Experiments. Cell Syst. 2016, 3, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Ay, F.; Lee, C.; Gulsoy, G.; Deng, X.; Cook, S.; Hesson, J.; Cavanaugh, C.; Ware, C.B.; Krumm, A.; et al. Using DNase Hi-C Techniques to Map Global and Local Three-Dimensional Genome Architecture at High Resolution. Methods 2018, 142, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and Accurate Long-Read Alignment with Burrows-Wheeler Transform. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R.; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marçais, G.; Kingsford, C. A fast, Lock-Free Approach for Efficient Parallel Counting of Occurrences of k-Mers. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 764–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonechnikov, K.; Golosova, O.; Fursov, M.; The UGENE Team. Unipro UGENE: A Unified Bioinformatics Toolkit. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1166–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and Applications. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Minimap2: Pairwise Alignment for Nucleotide Sequences. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3094–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Misawa, K.; Kuma, K.; Miyata, T. MAFFT: A Novel Method for Rapid Multiple Sequence Alignment Based on Fast Fourier Transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 3059–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, A. AliView: A Fast and Lightweight Alignment Viewer and Editor for Large Datasets. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 3276–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H. Protein-to-Genome Alignment with Miniprot. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahadevaiah, S.; Mittwoch, U.; Moses, M.J. Pachytene Chromosomes in Male and Female Mice Heterozygous for the Is(7;1)40H insertion. Chromosoma 1984, 90, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.L.; Del Cerro, A.; Fernández, A.; Díez, M. The Relationship Between Synapsis and Chiasma Distribution in Grasshopper Bivalents Heterozygous for Supernumerary Segments. Heredity 1993, 70, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Priore, L.; Pigozzi, M.I. Heterologous Synapsis and Crossover Suppression in Heterozygotes for a Pericentric Inversion in the Zebra Finch. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2015, 147, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogan, K.M.; Jarrell, G.H.; Ryder, E.J.; Greenbaum, I.F. Heterosynapsis and Axial Equalization of the Sex Chromosomes of the Northern Bobwhite quail. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 2008, 60, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henzel, J.V.; Nabeshima, K.; Schvarzstein, M.; Turner, B.E.; Villeneuve, A.M.; Hillers, K.J. An Asymmetric Chromosome Pair Undergoes Synaptic Adjustment and Crossover Redistribution During Caenorhabditis elegans Meiosis: Implications for Sex Chromosome Evolution. Genetics 2011, 187, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgasheva, A.; Malinovskaya, L.; Zadesenets, K.S.; Slobodchikova, A.; Shnaider, E.; Rubtsov, N.; Borodin, P. Highly Conservative Pattern of Sex Chromosome Synapsis and Recombination in Neognathae Birds. Genes 2021, 12, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisachov, A.P.; Trifonov, V.A.; Giovannotti, M.; Ferguson-Smith, M.A.; Borodin, P.M. Immunocytological Analysis of Meiotic Recombination in Two Anole Lizards (Squamata, Dactyloidae). Comp. Cytogenet. 2017, 11, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinovskaya, L.P.; Tishakova, K.; Shnaider, E.P.; Borodin, P.M.; Torgasheva, A.A. Heterochiasmy and Sexual Dimorphism: The Case of the Barn Swallow (Hirundo rustica, Hirundinidae, Aves). Genes 2020, 11, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Priore, L.; Pigozzi, M.I. DNA Organization along Pachytene Chromosome Axes and Its Relationship with Crossover Frequencies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durand, N.C.; Robinson, J.T.; Shamim, M.S.; Machol, I.; Mesirov, I.; Lander, E.S.; Aiden, E.L. Juicebox Provides a Visualization System for Hi-C Contact Maps with Unlimited Zoom. Cell Syst. 2016, 3, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukyanchikova, V.; Nuriddinov, M.; Belokopytova, P.; Taskina, A.; Liang, J.; Reijnders, M.J.M.F.; Ruzzante, L.; Feron, R.; Waterhouse, R.M.; Wu, Y.; et al. Anopheles Mosquitoes Reveal New Principles of 3D Genome Organization in Insects. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, V.H.; Laine, V.N.; Bosse, M.; van Oers, K.; Dibbits, B.; Visser, M.E.; Crooijmans, R.P.M.A.; Groenen, M.A.M. CNVs are Associated with Genomic Architecture in a Songbird. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Zhang, R.; Machado-Stredel, F.; Alström, P.; Johansson, U.S.; Irestedt, M.; Mays, H.L.; McKay, B.D.; Nishiumi, I.; Cheng, Y.; et al. Great Journey of Great Tits (Parus major group): Origin, Diversification and Historical Demographics of a Broadly Distributed Bird Lineage. J. Biogeogr. 2020, 47, 1585–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurgin, L.G.; Bosse, M.; Adriaensen, F.; Albayrak, T.; Barboutis, C.; Belda, E.; Bushuev, A.; Cecere, J.G.; Charmantier, A.; Cichon, M.; et al. The Great Tit HapMap project: A Continental-Scale Analysis of Genomic Variation in a Songbird. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2024, 24, e13969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvist, L.; Ruokonen, M.; Lumme, J.; Orell, M. The Colonization History and Present-Day Population Structure of the European Great Tit (Parus major major). Heredity 1999, 82, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvist, L.; Martens, J.; Higuchi, H.; Nazarenko, A.A.; Valchuk, O.P.; Orell, M. Evolution and Genetic Structure of the Great Tit (Parus major) Complex. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2003, 270, 1447–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, A.; Rohwer, S.; Drovetski, S.V.; Zink, R.M. Different Post-Pleistocene Histories of Eurasian Parids. J. Hered. 2006, 97, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, V.H. Structural Variants in the Great Tit Genome and Their Effect on Seasonal Timing. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, P.C.; Leo, P.J.; Pointon, J.J.; Harris, J.; Cremin, K.; Bradbury, L.A.; Stebbings, S.; Harrison, A.A. Australian Osteoporosis Genetics Consortium; Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium; et al. Exome-Wide Study of Ankylosing Spondylitis Demonstrates Additional Shared Genetic Background with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. NPJ Genom. Med. 2016, 1, 16008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonhomme, D.; Vaysset, H.; Ednacot, E.M.Q.; Rodrigues, V.; Salloum, Y.; Cury, J.; Wang, A.; Benchetrit, A.; Affaticati, P.; Trejo, V.H.; et al. A Human Homolog of SIR2 Antiphage Proteins Mediates Immunity via the Toll-like Receptor Pathway. Science 2025, 389, eadr8536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, M.J.; Jiggins, C.D. Supergenes and Their Role in Evolution. Heredity 2014, 113, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuttle, E.M.; Bergland, A.O.; Korody, M.L.; Brewer, M.S.; Newhouse, D.J.; Minx, P.; Stager, M.; Betuel, A.; Cheviron, Z.A.; Warren, W.C.; et al. Divergence and Functional Degradation of a Sex Chromosome-like Supergene. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traut, W.; Winking, H.; Adolph, S. An Extra Segment in Chromosome 1 of Wild Mus Musculus: A C-Band Positive Homogeneously Staining Region. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 1984, 38, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agulnik, S.; Adolph, S.; Winking, H.; Traut, W. Zoogeography of the Chromosome 1 HSR in Natural Populations of the House Mouse (Mus musculus). Hereditas 1993, 119, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borodin, P.M.; Gorlov, I.; Ladygina, T.Y. Double Insertion of Homogeneously Staining Regions in Chromosome 1 of Wild Mus Musculus Musculus: Effects on Chromosome Pairing and Recombination. J. Hered. 1990, 81, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traut, W.; Rahn, I.M.; Winking, H.; Kunze, B.; Weichehan, D. Evolution of a 6-200 Mb Long-Range Repeat Cluster in the Genus Mus. Chromosoma 2001, 110, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negorev, D.G.; Vladimirova, O.V.; Ivanov, A.; Rauscher, F.; Maul, G.G. Differential Role of Sp100 Isoforms in Interferon-Mediated Repression of Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Immediate-Early Protein Expression. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 8019–8029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habiger, C.; Jäger, G.; Walter, M.; Iftner, T.; Stubenrauch, F. Interferon Kappa Inhibits Human Papillomavirus 31 Transcription by Inducing Sp100 Proteins. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichenhan, D.; Traut, W.; Kunze, B.; Winking, H. Distortion of Mendelian Recovery Ratio for a Mouse HSR Is Caused by Maternal and Zygotic Effects. Genet. Res. 1996, 68, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade Silva, D.M.Z.; Akera, T. Meiotic Drive of Non-Centromeric Loci in Mammalian MII Eggs. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2023, 81, 102082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Experimental Procedure | Genotype | Sex | Number of Birds | Total Number of Birds per Procedure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population karyotyping | Mixed * | Male, female | 46 * | 46 * |

| Synapsis and recombination analysis | PMA1AS/S | Male, female | 14 | 19 |

| PMA1AS/M | Male, female | 5 | ||

| Hi-C sequencing | PMA1AS/S | Female | 1 | 2 |

| PMA1AS/M | Female | 1 | ||

| Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) | PMA1AS/S | Female | 2 | 4 |

| PMA1AS/M | Male | 2 | ||

| Nanopore sequencing | PMA1AS/M | Female | 1 | 1 |

| N PMA1AM/M | N PMA1AS/M | N PMA1AS/S | N Total | Frequency of PMA1AS/M | Frequency of PMA1AM | χ2 Test for HWE | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEMALES | 0 | 4 | 13 | 17 | 0.24 ± 0.11 | 0.12 ± 0.06 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Males | 0 | 4 | 22 | 26 | 0.15 ± 0.07 | 0.08 ± 0.04 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| Pooled | 0 | 8 | 35 | 43 | 0.19 ± 0.06 | 0.09 ± 0.03 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Siberian Population | European Population | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variant | Coordinates, Mb | Variant | Coordinates, Mb |

| Inversion | 3.50–56.87 | Inversion | 3–68 |

| CNV1 | 65.86–65.90 | CNV1 | 65.87–65.90 |

| CNV2 | 67.56–67.58 | CNV2 | 67.56–67.58 |

| CNV3 | 67.64–67.66 | CNV3 | 67.64–67.65 |

| CNV4 | 63.45–63.46 | CNVup1 | 63.44–63.46 |

| CNV5 | 63.46–63.56 | CNVup2 | 63.46–63.56 |

| CNV6 | 64.818–64.824 | - | - |

| CNV7 | 64.824–64.828 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Torgasheva, A.; Malinovskaya, L.; Nuriddinov, M.; Zadesenets, K.S.; Gridina, M.; Nurislamov, A.; Korableva, S.; Pristyazhnyuk, I.; Proskuryakova, A.; Tishakova, K.V.; et al. An Exceptionally Complex Chromosome Rearrangement in the Great Tit (Parus major): Genetic Composition, Meiotic Behavior and Population Frequency. Cells 2026, 15, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010052

Torgasheva A, Malinovskaya L, Nuriddinov M, Zadesenets KS, Gridina M, Nurislamov A, Korableva S, Pristyazhnyuk I, Proskuryakova A, Tishakova KV, et al. An Exceptionally Complex Chromosome Rearrangement in the Great Tit (Parus major): Genetic Composition, Meiotic Behavior and Population Frequency. Cells. 2026; 15(1):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010052

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorgasheva, Anna, Lyubov Malinovskaya, Miroslav Nuriddinov, Kira S. Zadesenets, Maria Gridina, Artem Nurislamov, Svetlana Korableva, Inna Pristyazhnyuk, Anastasiya Proskuryakova, Katerina V. Tishakova, and et al. 2026. "An Exceptionally Complex Chromosome Rearrangement in the Great Tit (Parus major): Genetic Composition, Meiotic Behavior and Population Frequency" Cells 15, no. 1: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010052

APA StyleTorgasheva, A., Malinovskaya, L., Nuriddinov, M., Zadesenets, K. S., Gridina, M., Nurislamov, A., Korableva, S., Pristyazhnyuk, I., Proskuryakova, A., Tishakova, K. V., Rubtsov, N. B., Fishman, V. S., & Borodin, P. (2026). An Exceptionally Complex Chromosome Rearrangement in the Great Tit (Parus major): Genetic Composition, Meiotic Behavior and Population Frequency. Cells, 15(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010052