Ovulatory Signal-Driven H3K4me3 and H3K27ac Remodeling in Mural Granulosa Cells Orchestrates Oocyte Maturation and Ovulation

Highlights

- During ovulatory signal-induced ovulation, a precisely timed transcriptional reprogramming in mural granulosa cells (MGCs) is evoked, with distinct temporal waves that reflect the progression from oocyte maturation to ovulatory response.

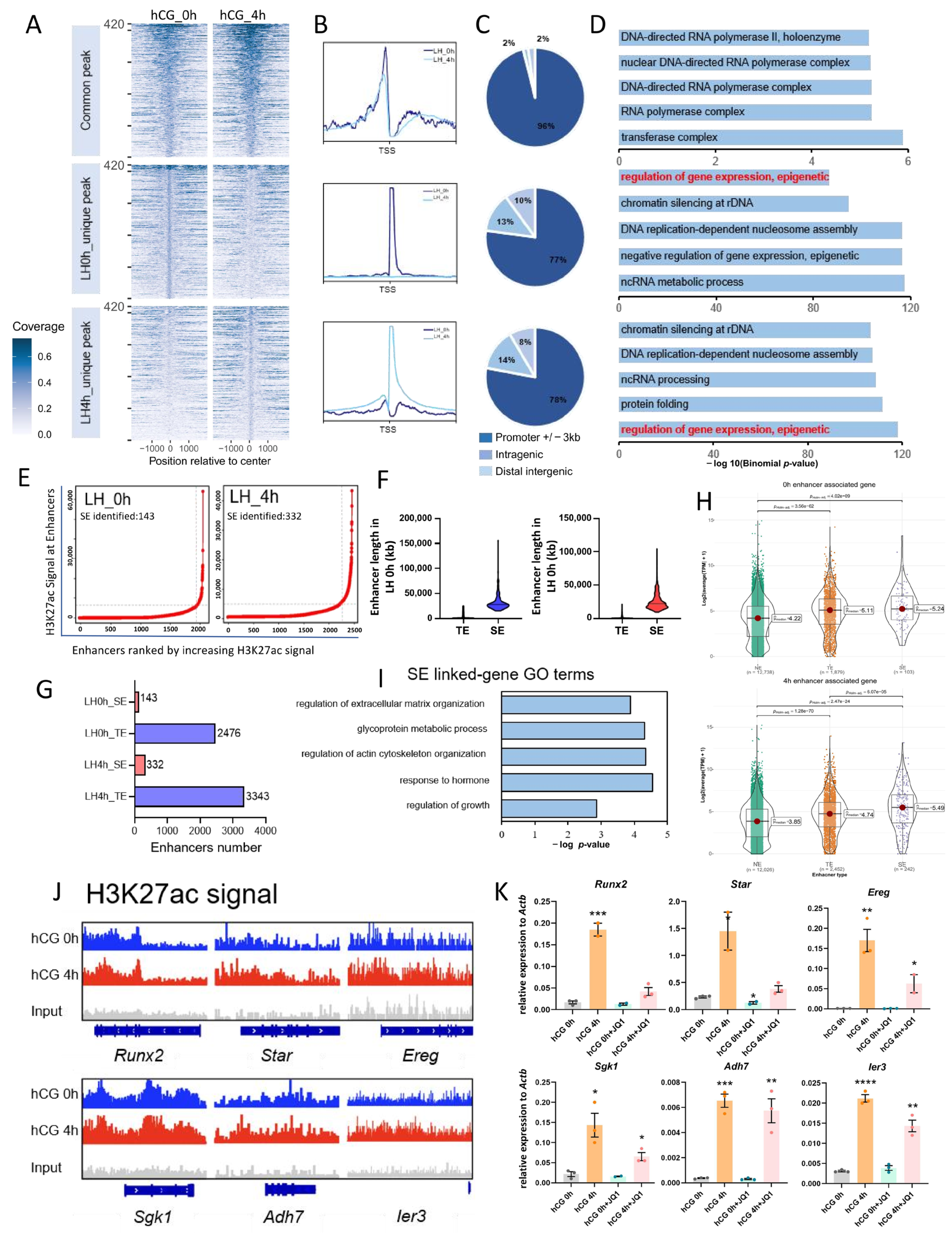

- H3K4me3 and H3K27ac represent two core histone-modification programs underlying LH-induced transcription. H3K4me3 activates target gene expression primarily by enriching in gene promoter regions; H3K27ac regulates MGCs transcription by establishing enhancers, especially SEs.

- Our study demonstrates that super-enhancers (SEs) constitute a key regulatory axis through which the ovulatory signal amplifies gene activation in MGCs.

- The integration of temporal transcriptional changes with dynamic promoter and SE remodeling provides a framework for how gonadotropins coordinate MGC function through chromatin architecture, offering new mechanistic insights into the epigenetic orchestration of follicular development.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Collection of Mouse MGCs

2.3. In Vitro Culture of Mouse MGCs

2.4. Inhibitor Treatment

2.5. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-qPCR)

2.6. Quality Assessment and Analysis of MGCs Transcriptome Data

2.7. CHIP-Seq Data Analysis

2.8. Super-Enhancer Analysis

2.9. Immunohistochemical Staining

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Transcriptome-Wide Changes Induced by LH/hCG in Mouse MGCs

3.2. Functional Enrichment Analysis of DEGs Induced by LH Signaling

3.3. LH Signaling Induces Dynamic Changes in H3K4me3 and H3K27ac in Mouse MGCs

3.4. Integrative Analysis of the Effects of H3K4me3 and H3K27ac Modifications on Transcriptional Activity in Mouse MGCs

3.5. H3K4me3 and H3K27ac Affect Transcriptional Activity of Mouse MGCs Through Promoters and Enhancers, Respectively

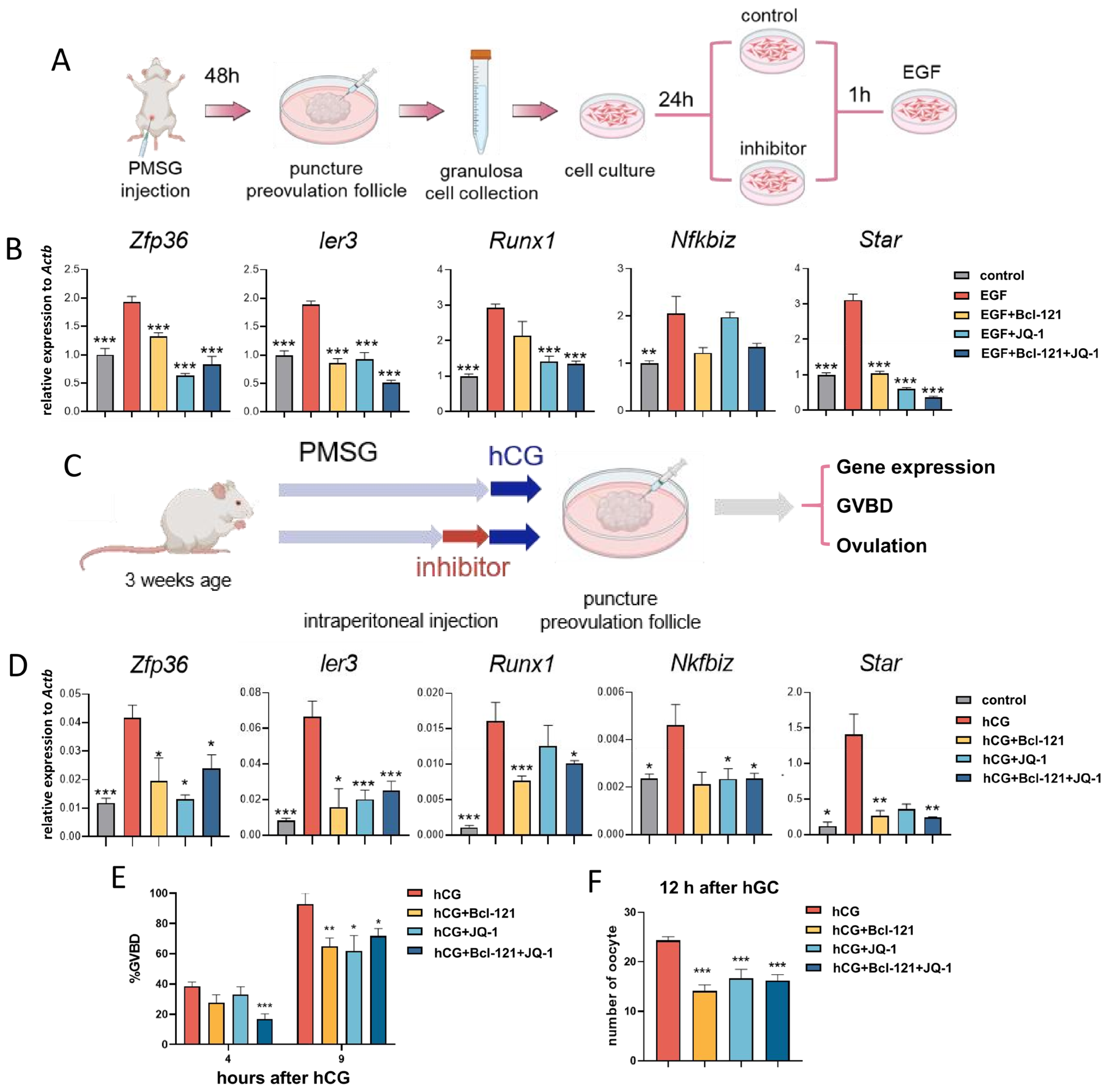

3.6. Disruption of H3K27ac and H3K4me3 Modifications Leads to Impaired Oocyte Maturation and Ovulation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LH | luteinizing hormone |

| MGCs | mural granulosa cells |

| SEs | super-enhancers |

| GCs | granulosa cells |

| CCs | cumulus cells |

| LHR | luteinizing hormone receptor |

| hCG | human chorionic gonadotropin |

| COC | cumulus–oocyte complex |

| GVBD | germinal vesicle breakdown |

| PB1 | first polar body |

| PCOS | polycystic ovary syndrome |

| CL | corpus luteum |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor |

| EGF | epidermal growth factor |

| EGFR | EGF receptor |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| CT | threshold cycle |

| TPM | transcripts per kilobase per million mapped reads |

| DEGs | differentially expressed genes |

| STEM | Short Time-series Expression Miner |

| ROSE | Rank Ordering of Super-Enhancers |

| TEs | typical enhancers |

| BSA | bovine serum albumin |

| ANOVA | one-way analysis of variance |

| NE | no enhancer |

References

- Alam, M.H.; Miyano, T. Interaction between growing oocytes and granulosa cells in vitro. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2020, 19, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wigglesworth, K.; Lee, K.B.; Emori, C.; Sugiura, K.; Eppig, J.J. Transcriptomic diversification of developing cumulus and mural granulosa cells in mouse ovarian follicles. Biol. Reprod. 2015, 92, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeppesen, J.V.; Kristensen, S.G.; Nielsen, M.E.; Humaidan, P.; Dal Canto, M.; Fadini, R.; Schmidt, K.T.; Ernst, E.; Yding, A.C. LH-receptor gene expression in human granulosa and cumulus cells from antral and preovulatory follicles. J. Clin. Endocr. Metab. 2012, 97, E1524–E1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Cai, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, M.; Liu, B.; Chen, Z.; Yang, T.; Fang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; et al. HDAC3 maintains oocyte meiosis arrest by repressing amphiregulin expression before the LH surge. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, F.; Teveroni, E.; Cicchinelli, M.; Iavarone, F.; Astorri, A.L.; Maulucci, G.; Serantoni, C.; Hatem, D.; Gallo, D.; Di Nardo, C.; et al. Secretory Profile Analysis of Human Granulosa Cell Line Following Gonadotropin Stimulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kon, H.; Tohei, A.; Hokao, R.; Shinoda, M. Estrous cycle stage-independent treatment of PMSG and hCG can induce superovulation in adult Wistar-Imamichi rats. Exp. Anim. 2005, 54, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Cai, Q.; Xu, Y. The Ubiquitin-CXCR4 Axis Plays an Important Role in Acute Lung Infection-Enhanced Lung Tumor Metastasis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 4706–4716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montag, M.; van der Ven, K.; Rosing, B.; van der Ven, H. Polar body biopsy: A viable alternative to preimplantation genetic diagnosis and screening. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2009, 18, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, L.A.; Egbert, J.R. Regulation of Mammalian Oocyte Meiosis by Intercellular Communication Within the Ovarian Follicle. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2017, 79, 237–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migone, F.F.; Cowan, R.G.; Williams, R.M.; Gorse, K.J.; Zipfel, W.R.; Quirk, S.M. In vivo imaging reveals an essential role of vasoconstriction in rupture of the ovarian follicle at ovulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 2294–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, D.L.; Robker, R.L. Molecular mechanisms of ovulation: Co-ordination through the cumulus complex. Hum. Reprod. Update 2007, 13, 289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espey, L.L. Current status of the hypothesis that mammalian ovulation is comparable to an inflammatory reaction. Biol. Reprod. 1994, 50, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macchiarelli, G.; Jiang, J.Y.; Nottola, S.A.; Sato, E. Morphological patterns of angiogenesis in ovarian follicle capillary networks. A scanning electron microscopy study of corrosion cast. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2006, 69, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.Y.; Liu, Z.; Shimada, M.; Sterneck, E.; Johnson, P.F.; Hedrick, S.M.; Richards, J.S. MAPK3/1 (ERK1/2) in ovarian granulosa cells are essential for female fertility. Science 2009, 324, 938–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.J.; Park, J.I.; Moon, W.J.; Dam, P.T.; Cho, M.K.; Chun, S.Y. Cumulus cell-expressed type I interferons induce cumulus expansion in mice. Biol. Reprod. 2015, 92, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapointe, E.; Boyer, A.; Rico, C.; Paquet, M.; Franco, H.L.; Gossen, J.; DeMayo, F.J.; Richards, J.S.; Boerboom, D. FZD1 regulates cumulus expansion genes and is required for normal female fertility in mice. Biol. Reprod. 2012, 87, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edson, M.A.; Nagaraja, A.K.; Matzuk, M.M. The Mammalian Ovary from Genesis to Revelation. Endocr. Rev. 2009, 30, 624–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.D. Models of luteinization. Biol. Reprod. 2000, 63, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romereim, S.M.; Summers, A.E.; Pohlmeier, W.E.; Zhang, P.; Hou, X.; Talbott, H.A.; Cushman, R.A.; Wood, J.R.; Davis, J.S.; Cupp, A.S. Gene expression profiling of bovine ovarian follicular and luteal cells provides insight into cellular identities and functions. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2017, 439, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierralta, W.D.; Kohen, P.; Castro, O.; Munoz, A.; Strauss, J.R.; Devoto, L. Ultrastructural and biochemical evidence for the presence of mature steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) in the cytoplasm of human luteal cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2005, 242, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlyczynska, E.; Kiezun, M.; Kurowska, P.; Dawid, M.; Pich, K.; Respekta, N.; Daudon, M.; Rytelewska, E.; Dobrzyn, K.; Kaminska, B.; et al. New Aspects of Corpus Luteum Regulation in Physiological and Pathological Conditions: Involvement of Adipokines and Neuropeptides. Cells 2022, 11, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, G.K.; Patra, M.K.; Singh, L.K.; Upmanyu, V.; Chakravarti, S.; Karikalan, M.; Bag, S.; Singh, S.K.; Das, G.K.; Kumar, H.; et al. Expression and functional role of kisspeptin and its receptor in the cyclic corpus luteum of buffalo (Bubalus bubalis). Theriogenology 2019, 130, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wulff, C.; Wilson, H.; Largue, P.; Duncan, W.C.; Armstrong, D.G.; Fraser, H.M. Angiogenesis in the human corpus luteum: Localization and changes in angiopoietins, tie-2, and vascular endothelial growth factor messenger ribonucleic acid. J. Clin. Endocr. Metab. 2000, 85, 4302–4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinagawa, M.; Tamura, I.; Maekawa, R.; Sato, S.; Shirafuta, Y.; Mihara, Y.; Okada-Matsumoto, M.; Taketani, T.; Asada, H.; Tamura, H.; et al. C/EBPbeta regulates Vegf gene expression in granulosa cells undergoing luteinization during ovulation in female rats. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carletti, M.Z.; Christenson, L.K. Rapid effects of LH on gene expression in the mural granulosa cells of mouse periovulatory follicles. Reproduction 2009, 137, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eini, F.; Novin, M.G.; Joharchi, K.; Hosseini, A.; Nazarian, H.; Piryaei, A.; Bidadkosh, A. Intracytoplasmic oxidative stress reverses epigenetic modifications in polycystic ovary syndrome. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2017, 29, 2313–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, S.; Shao, Y.; Su, Y.; Li, Q.; Wu, J.; Zhu, J.; Wen, H.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; et al. KLF5 Promotes Tumor Progression and Parp Inhibitor Resistance in Ovarian Cancer. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2304638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, S.; Bellefleur, A.; Beaulieu, E.; Beauparlant, C.J.; Bertolin, K.; Droit, A.; Schoonjans, K.; Murphy, B.D.; Gevry, N. The Ovulatory Signal Precipitates LRH-1 Transcriptional Switching Mediated by Differential Chromatin Accessibility. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Zhou, J.; Tan, T.K.; Chung, T.H.; Chen, Y.; Chooi, J.Y.; Sanda, T.; Fullwood, M.J.; Xiong, S.; Toh, S.; et al. Super Enhancer-Mediated Upregulation of HJURP Promotes Growth and Survival of t(4;14)-Positive Multiple Myeloma. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathy, K.; McKay, A.; Durinck, S.; Shi, M.; Dorighi, K.; Lam, C.; Liang, Y.; Shen, A.; Barnard, G.; Misaghi, S. Chromatin Accessibility Plays an Important Epigenetic Role on Antibody Expression from CMV Promoter and DNA Elements Flanking the CHO TI Host Landing-Pad. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 19, e202400487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Chen, L.; Han, Y.; Wu, F.; Yang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Huo, T.; Zhu, Y.; Yu, C.; Kim, H.; et al. Acetylation of histone H3K27 signals the transcriptional elongation for estrogen receptor alpha. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Hilbert, L.; Oda, H.; Wan, Y.; Heddleston, J.M.; Chew, T.L.; Zaburdaev, V.; Keller, P.; Lionnet, T.; Vastenhouw, N.; et al. Histone H3K27 acetylation precedes active transcription during zebrafish zygotic genome activation as revealed by live-cell analysis. Development 2019, 146, dev179127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madogwe, E.; Tanwar, D.K.; Taibi, M.; Schuermann, Y.; St-Yves, A.; Duggavathi, R. Global analysis of FSH-regulated gene expression and histone modification in mouse granulosa cells. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2020, 87, 1082–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, B.J.; Stocco, D.M. Expression of the steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein: A novel LH-induced mitochondrial protein required for the acute regulation of steroidogenesis in mouse Leydig tumor cells. Endocr. Res. 1995, 21, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Ren, P.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, W.; Ma, Y.; Lai, M.; Yu, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.L. Ovulatory signal-triggered chromatin remodeling in ovarian granulosa cells by HDAC2 phosphorylation activation-mediated histone deacetylation. Epigenetics Chromatin 2023, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Li, G.; Huang, Q.; Wen, J.; Deng, Y.; Jiang, J. TET3-mediated DNA demethylation and chromatin remodeling regulate T-2 toxin-induced human CYP1A1 expression and cytotoxicity in HepG2 cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 211, 115506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M.; Lee, D.; Panigone, S.; Horner, K.; Chen, R.; Theologis, A.; Lee, D.C.; Threadgill, D.W.; Conti, M. Luteinizing hormone-dependent activation of the epidermal growth factor network is essential for ovulation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007, 27, 1914–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigone, S.; Hsieh, M.; Fu, M.; Persani, L.; Conti, M. Luteinizing hormone signaling in preovulatory follicles involves early activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor pathway. Mol. Endocrinol. 2008, 22, 924–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Yue, W.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, X.; Yu, S.; Shen, Q.; Pan, Q.; Xu, W.; Zhang, R.; et al. Super-enhancers conserved within placental mammals maintain stem cell pluripotency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2090251177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giakountis, A.; Moulos, P.; Sarris, M.E.; Hatzis, P.; Talianidis, I. Smyd3-associated regulatory pathways in cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2017, 42, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Bai, K.; Song, Z.; Yang, M.; Li, M.; Wang, S.; Wang, X. H3K4me3 regulates the transcription of RSPO3 in dermal papilla cells to influence hair follicle morphogenesis and development. Epigenetics Chromatin 2025, 18, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−ΔΔC(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirafuta, Y.; Tamura, I.; Ohkawa, Y.; Maekawa, R.; Doi-Tanaka, Y.; Takagi, H.; Mihara, Y.; Shinagawa, M.; Taketani, T.; Sato, S.; et al. Integrated Analysis of Transcriptome and Histone Modifications in Granulosa Cells During Ovulation in Female Mice. Endocrinology 2021, 162, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loven, J.; Hoke, H.A.; Lin, C.Y.; Lau, A.; Orlando, D.A.; Vakoc, C.R.; Bradner, J.E.; Lee, T.I.; Young, R.A. Selective inhibition of tumor oncogenes by disruption of super-enhancers. Cell 2013, 153, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whyte, W.A.; Orlando, D.A.; Hnisz, D.; Abraham, B.J.; Lin, C.Y.; Kagey, M.H.; Rahl, P.B.; Lee, T.I.; Young, R.A. Master transcription factors and mediator establish super-enhancers at key cell identity genes. Cell 2013, 153, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.L.; Woods, D.C. Dynamics of avian ovarian follicle development: Cellular mechanisms of granulosa cell differentiation. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2009, 163, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, G.; George, J.W.; Clark, K.L.; Jonas, K.C.; Johnson, G.P.; Southekal, S.; Guda, C.; Hou, X.; Blum, H.R.; Eudy, J.; et al. Hypo-glycosylated hFSH drives ovarian follicular development more efficiently than fully-glycosylated hFSH: Enhanced transcription and PI3K and MAPK signaling. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 36, 1891–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Jo, M.; Lee, E.; Choi, D. AKT is involved in granulosa cell autophagy regulation via mTOR signaling during rat follicular development and atresia. Reproduction 2014, 147, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Xu, T.; Liu, C.; Wu, H.; Weng, L.; Cai, J.; Liang, N.; Ge, H. Correlation between ovarian follicular development and Hippo pathway in polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Ovarian Res. 2024, 17, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkolnik, K.; Tadmor, A.; Ben-Dor, S.; Nevo, N.; Galiani, D.; Dekel, N. Reactive oxygen species are indispensable in ovulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 1462–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.J.; Lin, P.C.; Zhou, S.; Barakat, R.; Bashir, S.T.; Choi, J.M.; Cacioppo, J.A.; Oakley, O.R.; Duffy, D.M.; Lydon, J.P.; et al. Progesterone Receptor Serves the Ovary as a Trigger of Ovulation and a Terminator of Inflammation. Cell Rep. 2020, 31, 107496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, T.; Naito, K.; Aoki, F.; Kume, S.; Tojo, H. Changes in histone modifications during in vitro maturation of porcine oocytes. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2005, 71, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Jiang, T.; Zhu, Y.; Ling, Z.; Yang, B.; Huang, L. A comparative investigation on H3K27ac enhancer activities in the brain and liver tissues between wild boars and domesticated pigs. Evol. Appl. 2022, 15, 1281–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baena, V.; Owen, C.M.; Uliasz, T.F.; Lowther, K.M.; Yee, S.; Terasaki, M.; Egbert, J.R.; Jaffe, L.A. Cellular Heterogeneity of the Luteinizing Hormone Receptor and Its Significance for Cyclic GMP Signaling in Mouse Preovulatory Follicles. Endocrinology 2020, 161, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yung, Y.; Aviel-Ronen, S.; Maman, E.; Rubinstein, N.; Avivi, C.; Orvieto, R.; Hourvitz, A. Localization of luteinizing hormone receptor protein in the human ovary. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 20, 844–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foot, N.J.; Dinh, D.T.; Emery-Corbin, S.J.; Yousef, J.M.; Dagley, L.F.; Russell, D.L. Comparative Analysis of the Progesterone Receptor Interactome in the Human Ovarian Granulosa Cell Line KGN and Other Female Reproductive Cells. Proteomics 2025, 25, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lydon, J.P.; Demayo, F.J.; Funk, C.R.; Mani, S.K.; Hughes, A.R.; Montgomery, C.A.; Shyamala, G.; Conneely, O.M.; Omalley, B.W. Mice Lacking Progesterone Receptor Exhibit Pleiotropic Reproductive Abnormalities. Genes Dev. 1995, 9, 2266–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, O.R.; Frazer, M.L.; Ko, C. Pituitary-ovary-spleen axis in ovulation. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 22, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, O.R.; Kim, H.; El-Amouri, I.; Lin, P.P.; Cho, J.; Bani-Ahmad, M.; Ko, C. Periovulatory Leukocyte Infiltration in the Rat Ovary. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 4551–4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdiec, A.; Bedard, D.; Rao, C.V.; Akoum, A. Human chorionic gonadotropin regulates endothelial cell responsiveness to interleukin 1 and amplifies the cytokine-mediated effect on cell proliferation, migration and the release of angiogenic factors. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2013, 70, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Park, J.Y.; Wilson, K.; Rosewell, K.L.; Brannstrom, M.; Akin, J.W.; Curry, T.J.; Jo, M. The expression of CXCR4 is induced by the luteinizing hormone surge and mediated by progesterone receptors in human preovulatory granulosa cells. Biol. Reprod. 2017, 96, 1256–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Bagchi, I.C.; Bagchi, M.K. Signaling by hypoxia-inducible factors is critical for ovulation in mice. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 3392–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockram, P.E.; Kist, M.; Prakash, S.; Chen, S.; Wertz, I.E.; Vucic, D. Ubiquitination in the regulation of inflammatory cell death and cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, V.; Marchese, A.; Majetschak, M. CXC Chemokine Receptor 4 Is a Cell Surface Receptor for Extracellular Ubiquitin. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 15566–15576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Zhang, Q.; Qian, X.; Li, J.; Qi, Q.; Sun, R.; Han, J.; Zhu, X.; Xie, M.; Guo, X.; et al. Extracellular ubiquitin promotes hepatoma metastasis by mediating M2 macrophage polarization via the activation of the CXCR4/ERK signaling pathway. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fan, Z.; Shliaha, P.V.; Miele, M.; Hendrickson, R.C.; Jiang, X.; Helin, K. H3K4me3 regulates RNA polymerase II promoter-proximal pause-release. Nature 2023, 615, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Nie, Y.; Xu, B.; Mu, C.; Tian, G.G.; Li, X.; Cheng, W.; Zhang, A.; Li, D.; Wu, J. Luteinizing Hormone Receptor Mutation (LHR(N316S)) Causes Abnormal Follicular Development Revealed by Follicle Single-Cell Analysis and CRISPR/Cas9. Interdiscip. Sci. 2024, 16, 976–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, F.; Wang, W.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, R.; An, L.; Tian, J.; Xi, G. Ovulatory Signal-Driven H3K4me3 and H3K27ac Remodeling in Mural Granulosa Cells Orchestrates Oocyte Maturation and Ovulation. Cells 2026, 15, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010034

Wang F, Wang W, Zhang S, Wang Y, Zhang R, An L, Tian J, Xi G. Ovulatory Signal-Driven H3K4me3 and H3K27ac Remodeling in Mural Granulosa Cells Orchestrates Oocyte Maturation and Ovulation. Cells. 2026; 15(1):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010034

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Furui, Wenjing Wang, Shuai Zhang, Yinjuan Wang, Ruimen Zhang, Lei An, Jianhui Tian, and Guangyin Xi. 2026. "Ovulatory Signal-Driven H3K4me3 and H3K27ac Remodeling in Mural Granulosa Cells Orchestrates Oocyte Maturation and Ovulation" Cells 15, no. 1: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010034

APA StyleWang, F., Wang, W., Zhang, S., Wang, Y., Zhang, R., An, L., Tian, J., & Xi, G. (2026). Ovulatory Signal-Driven H3K4me3 and H3K27ac Remodeling in Mural Granulosa Cells Orchestrates Oocyte Maturation and Ovulation. Cells, 15(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010034