Ameliorative Effects of Vitamin E and Lutein on Hydrogen Peroxide-Triggered Oxidative Cytotoxicity via Combined Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and Manipulations

2.2. Cell Viability Assay

2.3. ROS Assay

2.4. Antioxidant Measurements

2.5. RNA Extraction

2.6. Transcriptome Sample Preparation, Library Construction, and Sequencing

2.7. Transcriptome Data Analysis

2.8. Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR) Validation

2.9. Metabolites Extraction

2.10. Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography-Quadrupole Time-of-Flight-Tandem Mass Spectroscopy (UPLC-QTOF-MS/MS) Analysis

2.11. Metabolome Data Analysis

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

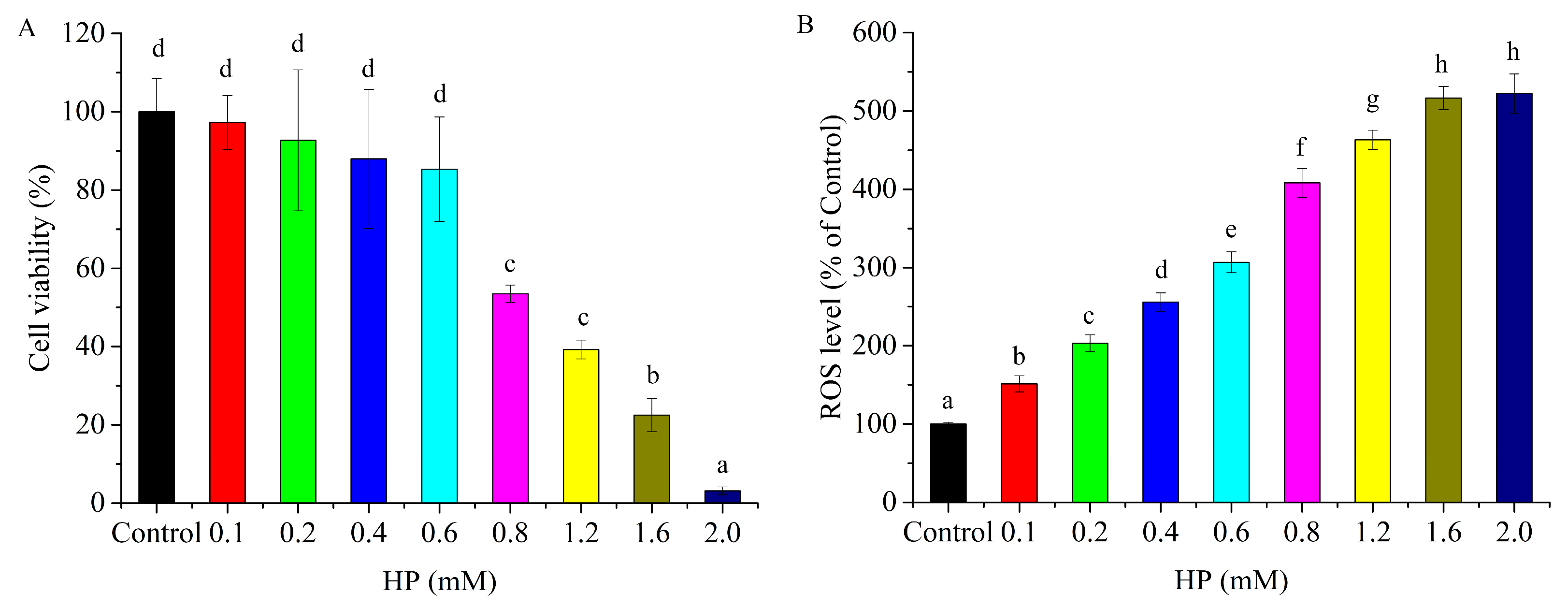

3.1. HP Caused HepG2 Cell Cytotoxicity

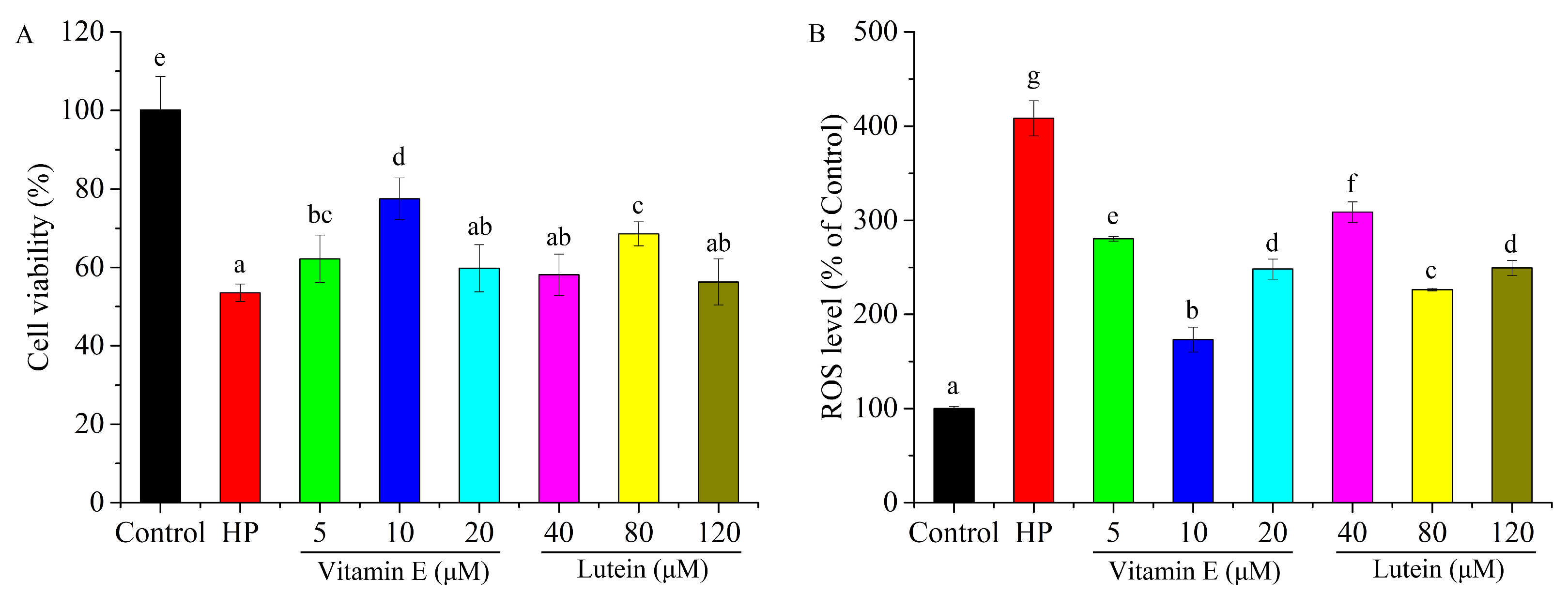

3.2. Effects of Vitamin E and Lutein on HepG2 Cell Cytotoxicity

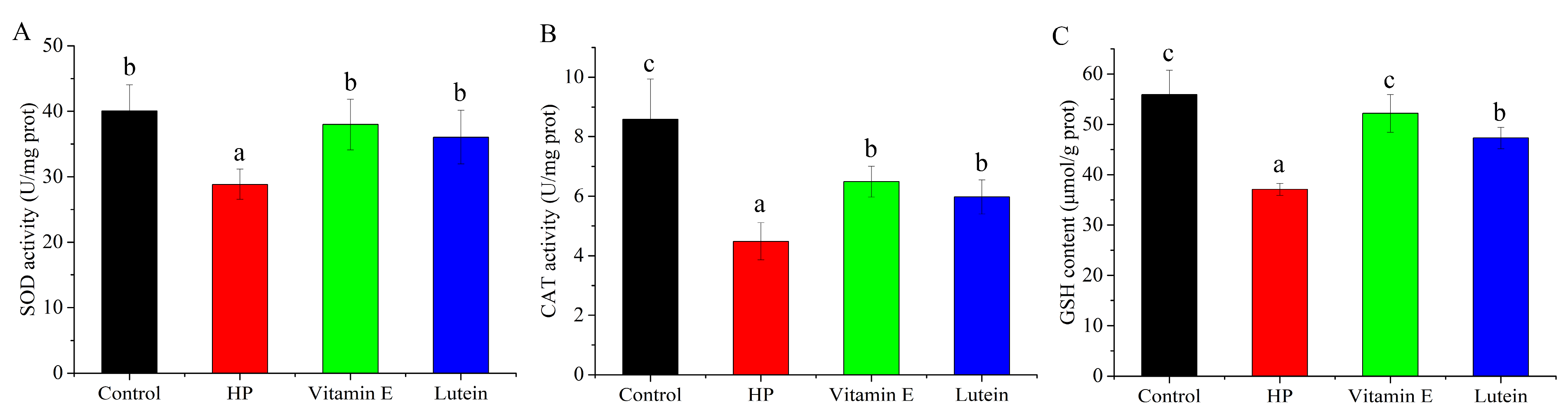

3.3. Effects of Vitamin E and Lutein on Antioxidant System of HepG2 Cell Under Oxidative Stress

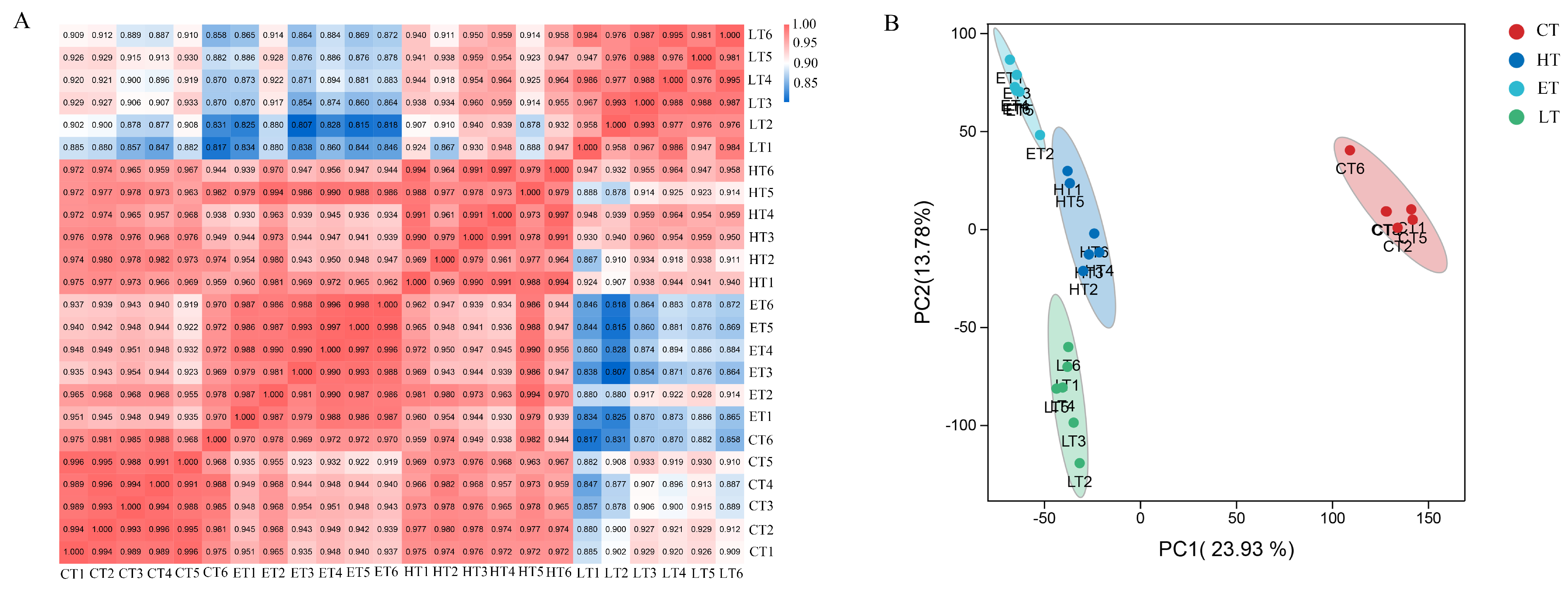

3.4. Transcriptome Data Quality Assessment of Vitamin E-, Lutein-, or HP-Treated HepG2 Cells

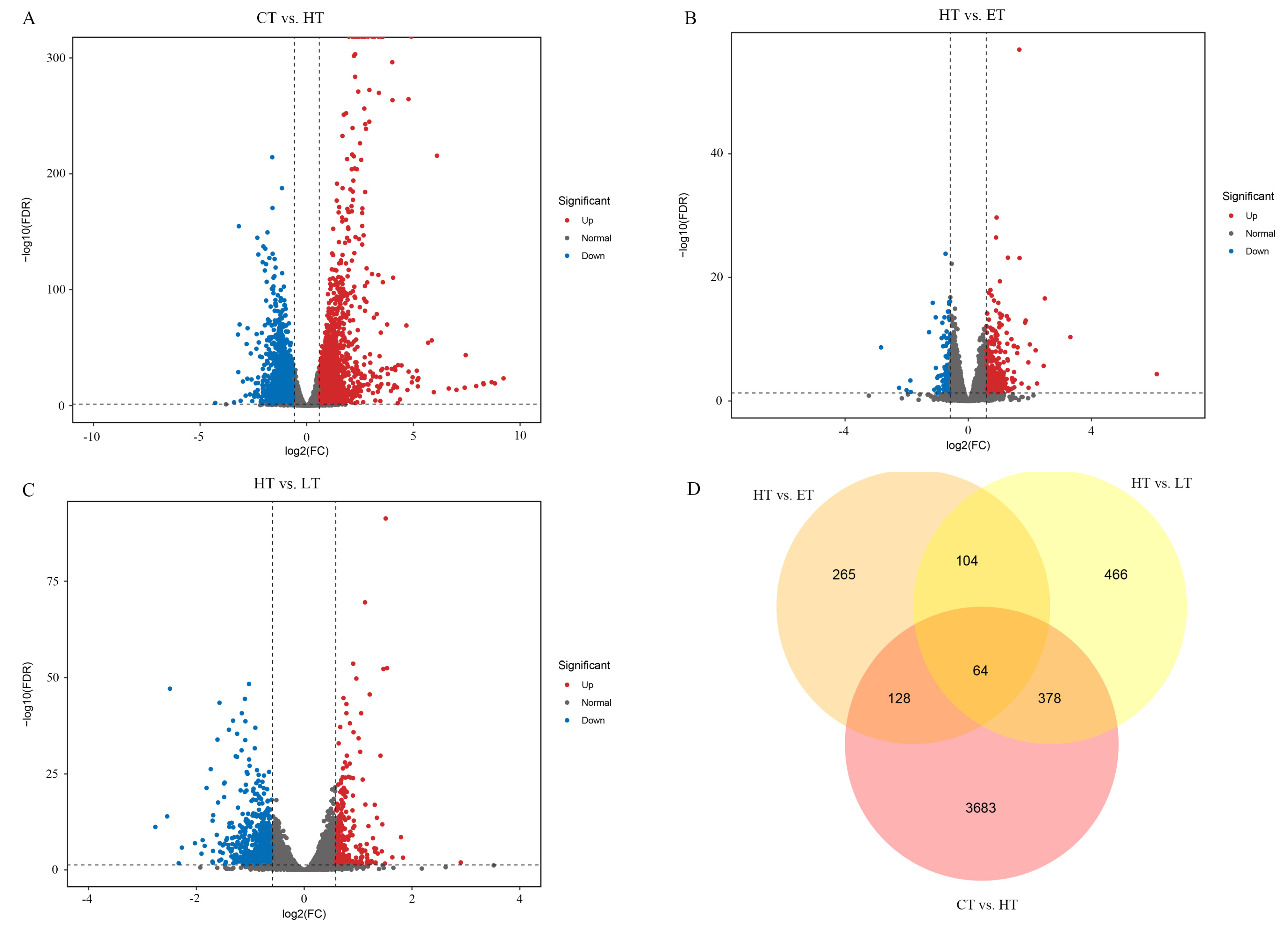

3.5. Characteristics of DEGs Profiling in Vitamin E-, Lutein-, or HP-Treated HepG2 Cells

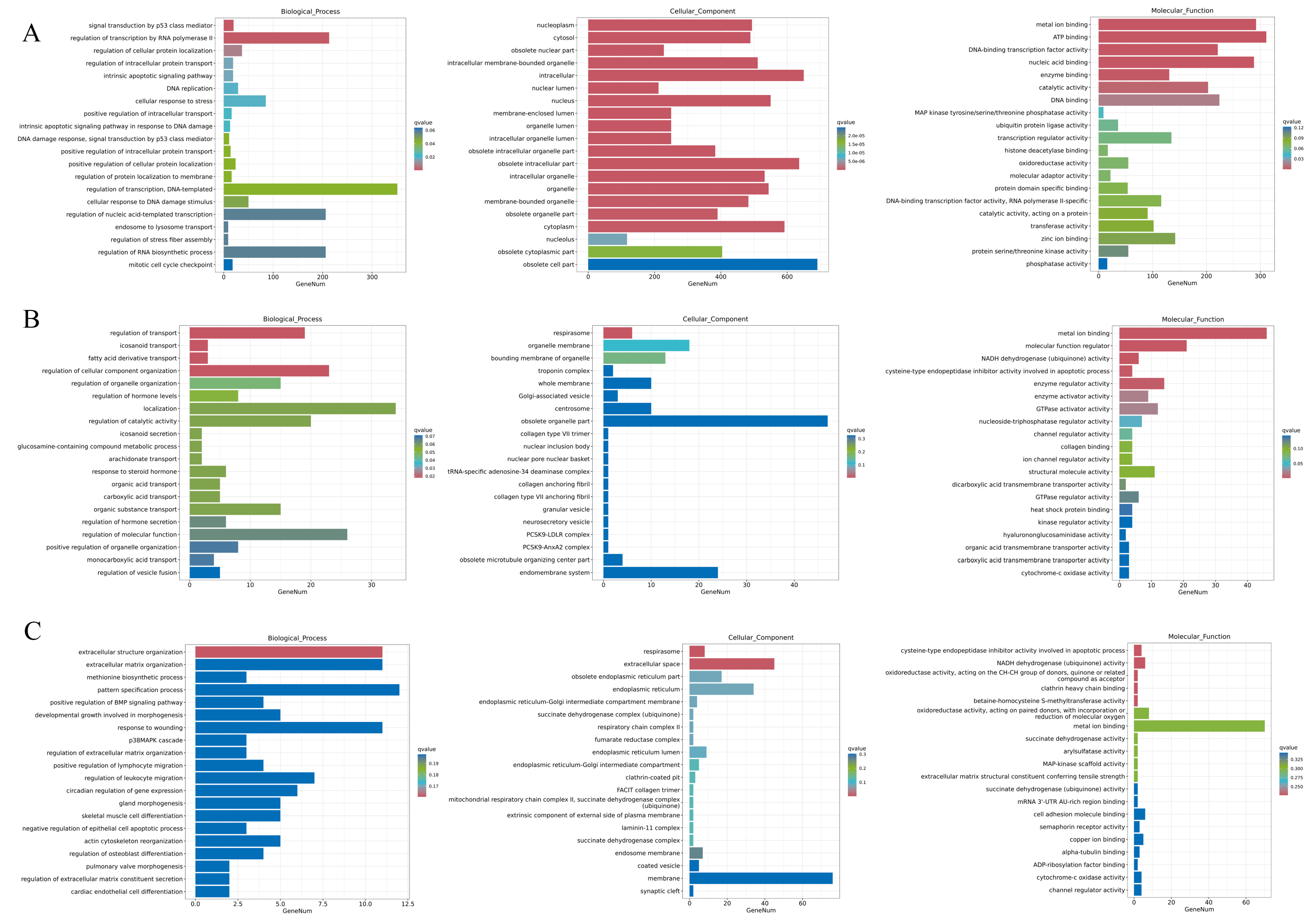

3.6. GO Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

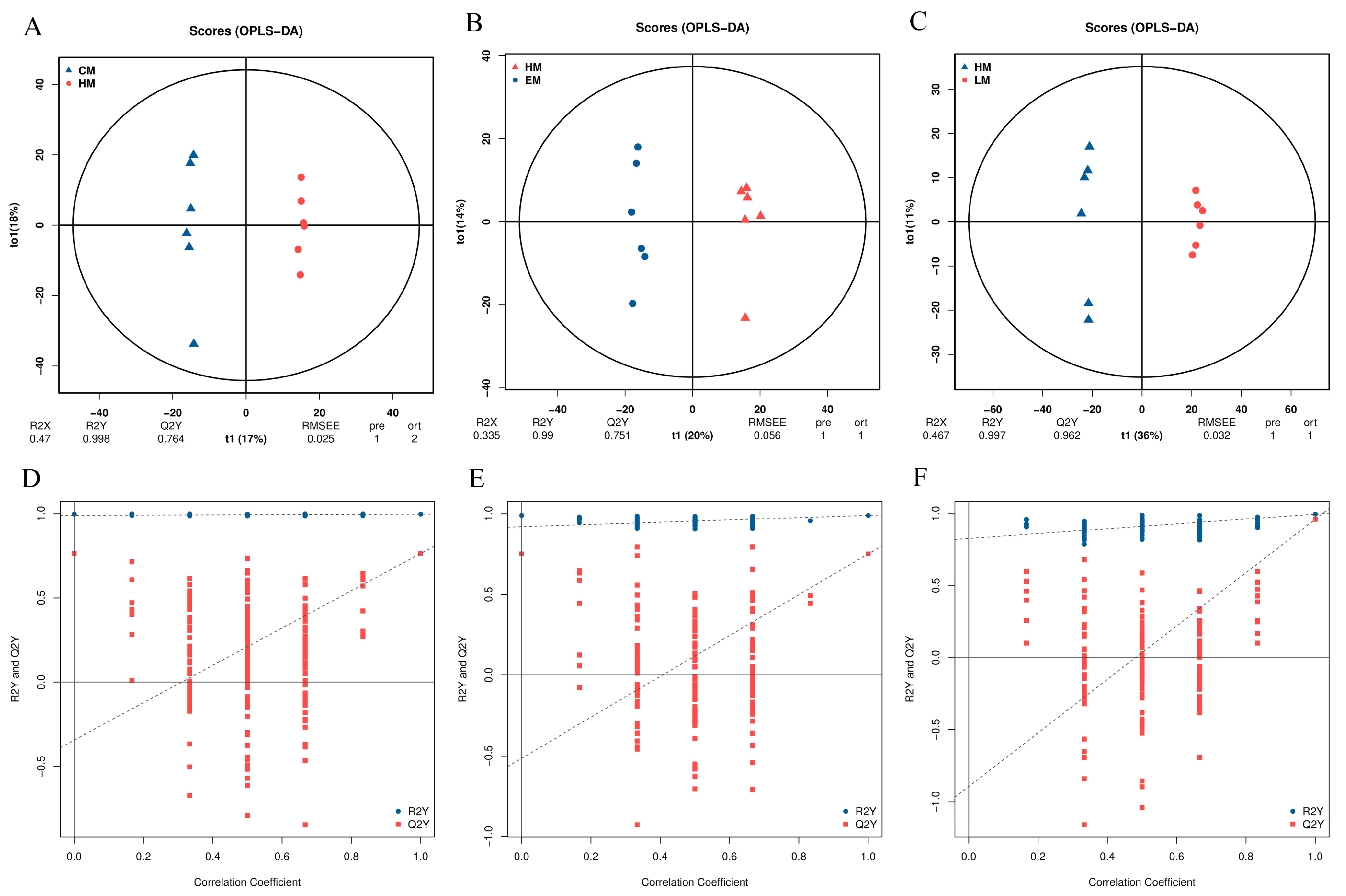

3.7. Metabolome Data Quality Assessment of Vitamin E-, Lutein-, or HP-Treated HepG2 Cells

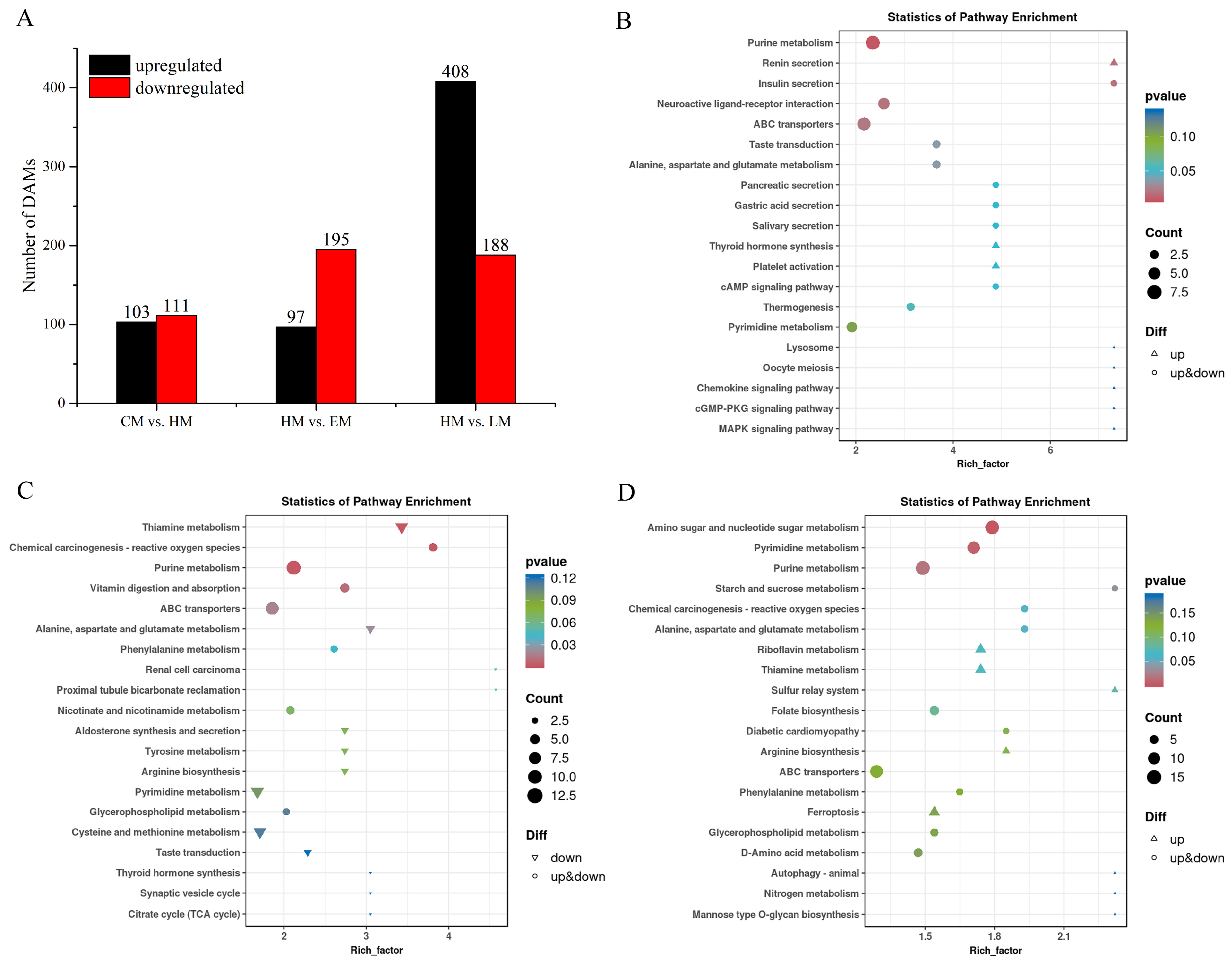

3.8. The Metabolic Pathway Analysis of Vitamin E-, Lutein-, or HP-Treated HepG2 Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| HP | Hydrogen peroxide |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium |

| CCK-8 | Cell Counting Kit-8 |

| DCFH-DA | 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| WST-1 | Water-soluble tetrazolium salt |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| FPKM | Fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction |

| QC | Quality control |

| UPLC-QTOF-MS/MS | Ultra-high Performance Liquid Chromatography-Quadrupole Time-of-flight-Tandem Mass Spectroscopy |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| FC | Fold change |

| OPLS-DA | Orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis |

| VIP | Variable importance in projection |

| ANOVA | One-way analysis of variance |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| TIC | Total ion current |

| MTs | Metallothioneins |

| NSTs | Nucleotide sugar transporters |

References

- Li, Z.Q.; Gao, Y.T.; Zhao, C.F.; An, R.; Wu, Y.L.; Huang, Z.P.; Ma, P.; Yang, X.; She, R.; Yang, X.Y. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory function of walnut green husk aqueous extract (WNGH-AE) on human hepatocellular carcinoma cells (HepG2) treated with t-BHP. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0318005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vakifahmetoglu-Norberg, H.; Ouchida, A.T.; Norberg, E. The role of mitochondria in metabolism and cell death. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 482, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertolle, M.E.; Guengerich, F.P. The relationships between cytochromes P450 and H2O2: Production, reaction, and inhibition. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2018, 186, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchida, Y.; Ferdousi, F.; Takahashi, S.; Isoda, H. Comprehensive transcriptome profiling of antioxidant activities by glutathione in human HepG2 cells. Molecules 2024, 29, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunthrarak, C.; Posridee, K.; Noisa, P.; Shim, S.; Thaiudom, S.; Oonsivilai, A.; Oonsivilai, R. Synergistic antioxidant and cytoprotective effects of Thunbergia laurifolia Lindl and Zingiber officinale extracts against PM2.5-induced oxidative stress in A549 and HepG2 cells. Foods 2025, 14, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, C.; Zhou, W.; Yu, M.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Cui, Y.; Cui, W. Vitamin E treatment improves the antioxidant capacity of patients receiving dialysis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2023, 67, e2300269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepidarkish, M.; Morvaridzadeh, M.; Akbari-Fakhrabadi, M.; Almasi-Hashiani, A.; Rezaeinejad, M.; Heshmati, J. Effect of omega-3 fatty acid plus vitamin E Co-Supplementation on lipid profile: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2019, 13, 1649–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enogieru, A.B.; Idemudia, O.U. Antioxidant activity and upregulation of BDNF in lead acetate–exposed rats following pretreatment with vitamin E. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2025, 34, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kavalappa, Y.P.; Gopal, S.S.; Ponesakki, G. Lutein inhibits breast cancer cell growth by suppressing antioxidant and cell survival signals and induces apoptosis. J. Cell. Physiol. 2021, 236, 1798–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armoza, A.; Haim, Y.; Basiri, A.; Wolak, T.; Paran, E. Tomato extract and the carotenoids lycopene and lutein improve endothelial function and attenuate inflammatory NF-κB signaling in endothelial cells. J. Hypertens. 2013, 31, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Lu, H.; Li, L.; Feng, M.; Zou, Z. Integration of transcriptomics and metabonomics revealed the protective effects of hemp seed oil against methionine-choline-deficient diet-induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 2096–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, V.; Arumugam, M.K.; Balachandran, S.; Boopathy, L.; Arumugam, S.; Srirangaramasamy, J.; Devanesan, S.; Suresh, A.; Sampath, S. Anticancer effects of monacolin X against human liver cancer cell line: Exploring the apoptosis using AO/EB and DCFHDA fluorescent staining. Luminescence 2025, 40, e70229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peskin, A.V.; Winterbourn, C.C. A microtiter plate assay for superoxide dismutase using a water-soluble tetrazolium salt (WST-1). Clin. Chim. Acta 2000, 293, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozmen, B.; Ozmen, D.; Erkin, E.; Güner, I.; Habif, S.; Bayindir, O. Lens superoxide dismutase and catalase activities in diabetic cataract. Clin. Biochem. 2002, 35, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, H.; Xu, J.; Bo, T.; Wang, W. Comparative transcriptome analysis uncovers roles of hydrogen sulfide for alleviating cadmium toxicity in Tetrahymena thermophila. BMC Genom. 2020, 22, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, J.; Chen, J.; Zeng, J.; Yang, Z.; Wang, C.; Hong, Z.; Zuo, Z. The protective effects of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) scale collagen hydrolysate against oxidative stress induced by tributyltin in HepG2 cells. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2019, 26, 3612–3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guha, S.; Majumder, K. Structural-features of food-derived bioactive peptides with anti-inflammatory activity: A brief review. J. Food Biochem. 2019, 43, e12531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Lamela, C.; Torrado-Agrasar, A.M. Effects of high-pressure processing (HPP) on antioxidant vitamins (A, C, and E) and antioxidant activity in fruit and vegetable preparations: A review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, X.; Wang, X.; Shen, W.; Ge, X. Preparation of the co-delivery system polymersome for blueberry anthocyanins/lutein and study on its antioxidant and transdermal absorption properties. Food Biosci. 2025, 71, 107382. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Wang, W.; Guo, C. Tetrahydroxy stilbene glucoside ameliorates H2O2-induced human brain microvascular endothelial cell dysfunction invitro by inhibiting oxidative stress and inflammatory responses. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 5219–5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, H.; Guo, S.; Wu, Z.; Nan, X.; Zhu, M.; Mao, K. Postharvest quality and metabolism changes of daylily flower buds treated with hydrogen sulfide during storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2024, 212, 112890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Zhao, C.; Shang, X.; Li, B.; Guo, J.; Wang, J.; Wu, B.; Fu, Y. Ameliorative effects of raisin polyphenol extract on oxidative stress and aging in vitro and in vivo via regulation of Sirt1–Nrf2 signaling pathway. Foods 2025, 14, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marí, M.; de Gregorio, E.; de Dios, C.; Roca-Agujetas, V.; Cucarull, B.; Tutusaus, A.; Morales, A.; Colell, A. Mitochondrial glutathione: Recent insights and role in disease. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mello, T.; Zanieri, F.; Ceni, E.; Galli, A. Oxidative stress in the healthy and wounded hepatocyte: A cellular organelles perspective. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 8327410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. p53 and its downstream proteins as molecular targets of cancer. Mol. Carcinog. 2006, 45, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayalakshmi, P.; Indu, S.; Ireen, C.; Manjunathan, R.; Rajalakshmi, M. Octyl gallate and gallic acid isolated from Terminalia bellirica circumvent breast cancer progression by enhancing the intrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway and elevating the levels of anti-oxidant enzymes. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2023, 195, 7214–7235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakiu, R.; Pacchini, S.; Piva, E.; Schumann, S.; Tolomeo, A.M.; Ferro, D.; Irato, P.; Santovito, G. Metallothionein expression as a physiological response against metal toxicity in the striped rockcod Trematomus hansoni. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashikuni, Y.; Sainz, J.; Nakamura, K.; Takaoka, M.; Enomoto, S.; Iwata, H.; Tanaka, K.; Sahara, M.; Hirata, Y.; Nagai, R.; et al. The ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCG2 protects against pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure by promoting angiogenesis and antioxidant response. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012, 32, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, D.; Karki, K.; Negi, R.; Khanna, S.; Khanna, R.S.; Khanna, H.D. NF-κB p65 subunit DNA-binding activity: Association with depleted antioxidant levels in breast carcinoma patients. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2013, 67, 1275–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skulachev, V.P.; Antonenko, Y.N.; Cherepanov, D.A.; Chernyak, B.V.; Izyumov, D.S.; Khailova, L.S.; Klishin, S.S.; Korshunova, G.A.; Lyamzaev, K.G.; Pletjushkina, O.Y.; et al. Prevention of cardiolipin oxidation and fatty acid cycling as two antioxidant mechanisms of cationic derivatives of plastoquinone (SkQs). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1797, 878–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, M.; Shivanandappa, T. Endosulfan causes oxidative stress in the liver and brain that involves inhibition of NADH dehydrogenase and altered antioxidant enzyme status in rat. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 239, 113593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpi-Santos, R.; de Melo Reis, R.A.; Gomes, F.C.A.; Calaza, K.C. Contribution of Müller cells in the diabetic retinopathy development: Focus on oxidative stress and inflammation. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, G.; Ayalew, H.; Mahmood, T.; Mercier, Y.; Wang, J.; Lin, J.; Wu, S.; Qiu, K.; Qi, G.; Zhang, H. Methionine and vitamin E supplementation improve production performance, antioxidant potential, and liver health in aged laying hens. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, E.C.; D’Antuono, M.; Jermakowicz, A.M.; Ayad, N.G. Methionine cycle inhibition disrupts antioxidant metabolism and reduces glioblastoma cell survival. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 108349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, F.; Han, B.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, X.; Pang, T.; Fan, Y. The Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor vardenafil improves the activation of BMP signaling in response to hydrogen peroxide. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2020, 34, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.H.; Babu, D.; Siraki, A.G. Interactions of the antioxidant enzymes NAD(P)H: Quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) and NRH: Quinone oxidoreductase 2 (NQO2) with pharmacological agents, endogenous biochemicals and environmental contaminants. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2021, 345, 109574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Yang, C.; Chai, S.; Guo, H.; Seim, I.; Yang, G. Evolutionary impacts of purine metabolism genes on mammalian oxidative stress adaptation. Zool. Res. 2022, 43, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, C.; Zatz, R. Linking oxidative stress, the renin-angiotensin system, and hypertension. Hypertension 2011, 57, 373–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, L.; Menikdiwela, K.; LeMieux, M.; Dufour, J.M.; Kaur, G.; Kalupahana, N.; Moustaid-Moussa, N. The renin angiotensin system, oxidative stress and mitochondrial function in obesity and insulin resistance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 1106–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Hu, J.; Zhu, X.; Yin, H.; Yin, J. Oxidative stress-mediated up-regulation of ABC transporters in lung cancer cells. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2022, 36, e23095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kartal, B.; Akcay, A.; Palabiyik, B. Oxidative stress upregulates the transcription of genes involved in thiamine metabolism. Turk. J. Biol. 2018, 42, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, W.; Li, R.; Liu, D.; Lu, H.; He, Z.; Gu, S. Comparative neurotoxic effects and mechanism of cadmium chloride and cadmium sulfate in neuronal cells. Environ. Int. 2025, 203, 109749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copp, R.P.; Wisniewski, T.; Hentati, F.; Larnaout, A.; Hamida, M.B.; Kayden, H.J. Localization of α-tocopherol transfer protein in the brains of patients with ataxia with vitamin E deficiency and other oxidative stress related neurodegenerative disorders. Brain Res. 1999, 822, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.; Ghosh, S.K. Nucleotide sugar transporters of Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba invadens involved in chitin synthesis. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2019, 234, 111224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Wang, D.; Nobile, C.J.; Dong, D.; Ni, Q.; Su, T.; Jiang, C.; Peng, Y. Systematic identification and characterization of five transcription factors mediating the oxidative stress response in Candida albicans. Microb. Pathog. 2024, 187, 106507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Kuang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, H.; Xie, J. GPX3-mediated oxidative stress affects pyrimidine metabolism levels in stomach adenocarcinoma via the AMPK/mTOR pathway. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2024, 2024, 6875417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, Y. Sucrose metabolism: Gateway to diverse carbon use and sugar signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2014, 65, 33–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lv, H.; He, Y.; Guo, S. Ameliorative Effects of Vitamin E and Lutein on Hydrogen Peroxide-Triggered Oxidative Cytotoxicity via Combined Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis. Cells 2025, 14, 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14242020

Lv H, He Y, Guo S. Ameliorative Effects of Vitamin E and Lutein on Hydrogen Peroxide-Triggered Oxidative Cytotoxicity via Combined Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis. Cells. 2025; 14(24):2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14242020

Chicago/Turabian StyleLv, Hongrui, Yongji He, and Shang Guo. 2025. "Ameliorative Effects of Vitamin E and Lutein on Hydrogen Peroxide-Triggered Oxidative Cytotoxicity via Combined Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis" Cells 14, no. 24: 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14242020

APA StyleLv, H., He, Y., & Guo, S. (2025). Ameliorative Effects of Vitamin E and Lutein on Hydrogen Peroxide-Triggered Oxidative Cytotoxicity via Combined Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis. Cells, 14(24), 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14242020