The Potential Clinical Relevance of Necrosis–Necroptosis Pathways for Hypoxic–Ischaemic Encephalopathy

Highlights

- Necroptosis makes a major contribution to both early and delayed brain injury after perinatal hypoxia-ischaemia.

- Necroptotic signalling starts soon after hypoxia–ischaemia, remains active into the tertiary phase and is only partly suppressed by hypothermia.

- Necroptosis and its upstream inflammatory drivers are potentially viable targets for adjunct therapies.

- Recognising necroptosis as a key pathway suggests new approaches to alleviate cell death in future neuroprotective trials.

Abstract

1. Background

2. Necrosis Versus Necroptosis

3. Other Important Cell Death Pathways

- Anoikis is a distinct intrinsic apoptosis triggered by loss of integrin-mediated cell anchorage and has been demonstrated in neonatal rodent HI models [42,43,44]. It is thought to contribute to neuronal death when extracellular matrix connections are disrupted, although this remains to be confirmed in human neonatal brain injury.

- Autophagy-dependent cell death is supported by evidence from multiple animal models and observations in human infants [45,46,47,48]. This form of self-digestion-related death typically arises in the secondary phase and is marked by accumulation of autophagosomes and impaired autophagic flux in vulnerable neurons [49].

- Ferroptosis, an iron-catalysed, lipid peroxidation-driven cell death, has been shown to contribute to hippocampal neuron injury in neonatal rodent HI models [55,56]. Although direct demonstration of ferroptosis in human HIE is limited, ferroptosis-associated markers like iron accumulation are apparent in infant brains measured with MRI [57].

- Lysosome-dependent cell death, involving lysosomal membrane permeabilization and release of proteases, is suggested to exacerbate HI brain injury in rodent studies [58]. Neonatal HI disrupts neural lysosomal integrity and protein distribution [58], which can amplify cellular injury, although there is still no clear evidence of this mechanism in human neonates.

- Mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT)-driven necrosis is another injury mechanism reported in rodent and piglet studies of neonatal HI [59,60,61,62,63]. Excessive opening of the mitochondrial permeability pore during the secondary energy failure leads to energy collapse and necrotic cell death; this has made mitochondria a therapeutic target, but interventions like cyclosporine (an MPT blocker) have had mixed success in improving outcomes [60,62].

- NETotic cell death is another recently described cell death pathway wherein neutrophils release extracellular traps (NETs) that can kill cells and propagate inflammation. Initially recognised in animal studies of neonatal infection [64], NETosis has more recently been observed after neonatal HI in rodents even during therapeutic hypothermia [65], indicating that neutrophil infiltration and NET release in the injured brain may sustain inflammation. Importantly, potentially this may be a part of why cooling alone is not fully protective.

- Parthanatos is a distinct, caspase-independent death pathway triggered by intense metabolic stress that stimulates poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1), leading to the release of apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) from mitochondria [66]. This mechanism causes a form of cell death resembling necrosis and can occur rapidly after HI [67]. However, despite early evidence of parthanatos-mediated neuronal death in neonatal HI, neuroprotective strategies targeting parthanatos have had inconsistent effects [68].

- Pyroptosis is an inflammatory form of programmed cell death governed by the NLRP3 inflammasome and executed by caspase-1. It has been demonstrated in neonatal rodents after HI [69,70]. Further, pyroptosis-associated markers have been consistently detected in the brains of human infants dying with HIE [71].

4. Accidental Necrosis Is the Primary Cell Death Pathway During Hypoxia–Ischemia

5. Apoptosis and Necrosis During the Secondary Phase After Hypoxia–Ischemia

6. Is This Early Form of Necrosis, Necroptosis?

7. Tertiary Phase and Necroptosis

8. When Is Late Necroptosis Initiated?

9. Effects of Hypothermia on Cell Death Pathways

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Lee, A.C.; Kozuki, N.; Blencowe, H.; Vos, T.; Bahalim, A.; Darmstadt, G.L.; Niermeyer, S.; Ellis, M.; Robertson, N.J.; Cousens, S.; et al. Intrapartum-related neonatal encephalopathy incidence and impairment at regional and global levels for 2010 with trends from 1990. Pediatr. Res. 2013, 74, 50–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuck, T.A.; Rice, M.M.; Bailit, J.L.; Grobman, W.A.; Reddy, U.M.; Wapner, R.J.; Thorp, J.M.; Caritis, S.N.; Prasad, M.; Tita, A.T.; et al. Preterm neonatal morbidity and mortality by gestational age: A contemporary cohort. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 215, 103.e101–103.e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salhab, W.A.; Perlman, J.M. Severe fetal acidemia and subsequent neonatal encephalopathy in the larger premature infant. Pediatr. Neurol. 2005, 32, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalak, L.F.; Rollins, N.; Morriss, M.C.; Brion, L.P.; Heyne, R.; Sanchez, P.J. Perinatal acidosis and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in preterm infants of 33 to 35 weeks’ gestation. J. Pediatr. 2012, 160, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopagondanahalli, K.R.; Li, J.; Fahey, M.C.; Hunt, R.W.; Jenkin, G.; Miller, S.L.; Malhotra, A. Preterm Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy. Front. Pediatr. 2016, 4, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battin, M.; Sadler, L.; Masson, V.; Farquhar, C. Neonatal Encephalopathy Working Group of the, P. Neonatal encephalopathy in New Zealand: Demographics and clinical outcome. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2016, 52, 632–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, M.; Agren, J.; Norden-Lindeberg, S.; Ohlin, A.; Hanson, U. Neonatal encephalopathy and the association to asphyxia in labor. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 211, 667.e1–667.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshiro, R.; Mdoe, P.; Perlman, J.M. A Global View of Neonatal Asphyxia and Resuscitation. Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawn, J.E.; Cousens, S.; Zupan, J.; Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team. 4 million neonatal deaths: When? Where? Why? Lancet 2005, 365, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, N.J.; Kuint, J.; Counsell, T.J.; Rutherford, T.A.; Coutts, A.; Cox, I.J.; Edwards, A.D. Characterization of cerebral white matter damage in preterm infants using 1H and 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2000, 20, 1446–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penrice, J.; Cady, E.B.; Lorek, A.; Wylezinska, M.; Amess, P.N.; Aldridge, R.F.; Stewart, A.; Wyatt, J.S.; Reynolds, E.O. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the brain in normal preterm and term infants, and early changes after perinatal hypoxia-ischemia. Pediatr. Res. 1996, 40, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrice, J.; Lorek, A.; Cady, E.B.; Amess, P.N.; Wylezinska, M.; Cooper, C.E.; D’Souza, P.; Brown, G.C.; Kirkbride, V.; Edwards, A.D.; et al. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the brain during acute hypoxia-ischemia and delayed cerebral energy failure in the newborn piglet. Pediatr. Res. 1997, 41, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorek, A.; Takei, Y.; Cady, E.B.; Wyatt, J.S.; Penrice, J.; Edwards, A.D.; Peebles, D.; Wylezinska, M.; Owen-Reece, H.; Kirkbride, V.; et al. Delayed (“secondary”) cerebral energy failure after acute hypoxia-ischemia in the newborn piglet: Continuous 48-h studies by phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Pediatr. Res. 1994, 36, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennet, L.; Booth, L.; Malpas, S.C.; Quaedackers, J.S.; Jensen, E.; Dean, J.; Gunn, A.J. Acute systemic complications in the preterm fetus after asphyxia: Role of cardiovascular and blood flow responses. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2006, 33, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallard, E.C.; Williams, C.E.; Johnston, B.M.; Gluckman, P.D. Increased vulnerability to neuronal damage after umbilical cord occlusion in fetal sheep with advancing gestation. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1994, 170, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keunen, H.; Blanco, C.E.; van Reempts, J.L.; Hasaart, T.H. Absence of neuronal damage after umbilical cord occlusion of 10, 15, and 20 minutes in midgestation fetal sheep. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1997, 176, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleiss, B.; Gressens, P. Tertiary mechanisms of brain damage: A new hope for treatment of cerebral palsy? Lancet Neurol. 2012, 11, 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

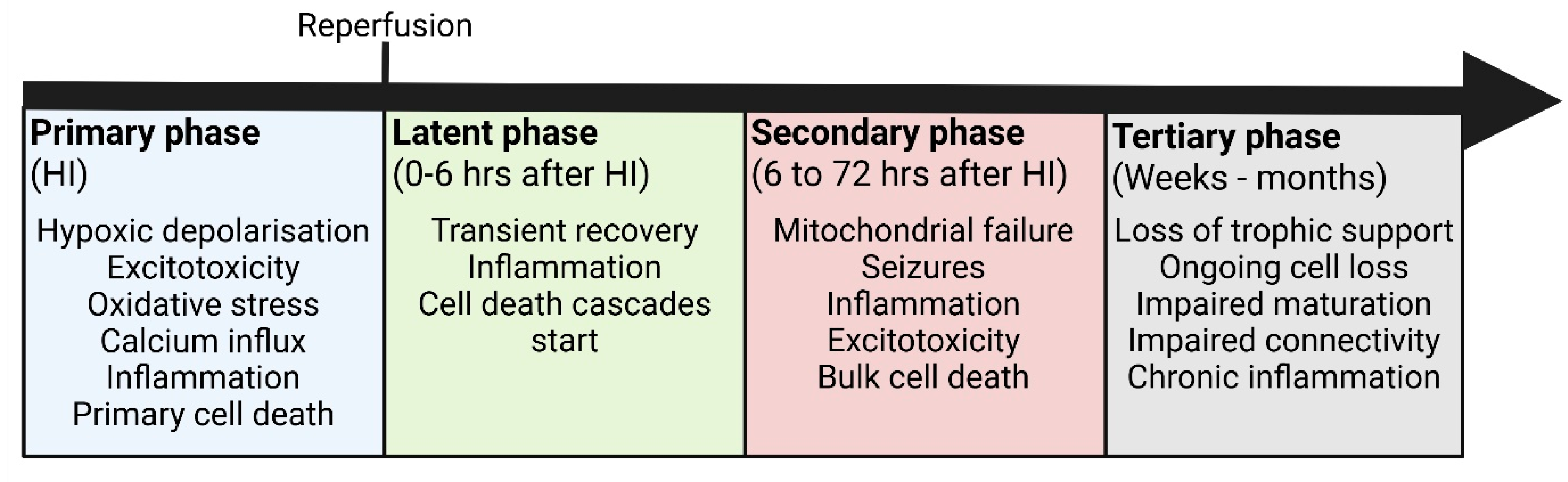

- Wassink, G.; Gunn, E.R.; Drury, P.P.; Bennet, L.; Gunn, A.J. The mechanisms and treatment of asphyxial encephalopathy. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagberg, H.; David Edwards, A.; Groenendaal, F. Perinatal brain damage: The term infant. Neurobiol. Dis. 2016, 92, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, S.K.; Lear, C.A.; Galinsky, R.; Wassink, G.; Davidson, J.O.; Juul, S.; Robertson, N.J.; Gunn, A.J.; Bennet, L. The fetus at the tipping point: Modifying the outcome of fetal asphyxia. J. Physiol. 2018, 596, 5571–5592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Heuij, L.G.; Fraser, M.; Miller, S.L.; Jenkin, G.; Wallace, E.M.; Davidson, J.O.; Lear, C.A.; Lim, R.; Wassink, G.; Gunn, A.J.; et al. Delayed intranasal infusion of human amnion epithelial cells improves white matter maturation after asphyxia in preterm fetal sheep. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2019, 39, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, J.O.; Gonzalez, F.; Gressens, P.; Gunn, A.J.; Newborn Brain Society, G.; Publications, C. Update on mechanisms of the pathophysiology of neonatal encephalopathy. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021, 26, 101267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lear, B.A.; Lear, C.A.; Davidson, J.O.; Sae-Jiw, J.; Lloyd, J.M.; Gunn, A.J.; Bennet, L. Tertiary cystic white matter injury as a potential phenomenon after hypoxia-ischaemia in preterm f sheep. Brain Commun. 2021, 3, fcab024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lear, B.A.; Lear, C.A.; Dhillon, S.K.; Davidson, J.O.; Gunn, A.J.; Bennet, L. Evolution of grey matter injury over 21 days after hypoxia-ischaemia in preterm fetal sheep. Exp. Neurol. 2023, 363, 114376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northington, F.J.; Chavez-Valdez, R.; Martin, L.J. Neuronal cell death in neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. Ann. Neurol. 2011, 69, 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Chang, E.; Zhao, H.; Ma, D. Regulated cell death in hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy: Recent development and mechanistic overview. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, L.J.; Shi, L.; Hoerder-Suabedissen, A.; Molnar, Z. Neonatal Hypoxia Ischaemia: Mechanisms, Models, and Therapeutic Challenges. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arcy, M.S. Cell death: A review of the major forms of apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy. Cell Biol. Int. 2019, 43, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerasinghe, P.; Buja, L.M. Oncosis: An important non-apoptotic mode of cell death. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2012, 93, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festjens, N.; Vanden Berghe, T.; Vandenabeele, P. Necrosis, a well-orchestrated form of cell demise: Signalling cascades, important mediators and concomitant immune response. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1757, 1371–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.; Mu, W. Necrostatin-1 and necroptosis inhibition: Pathophysiology and therapeutic implications. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 163, 105297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degterev, A.; Huang, Z.; Boyce, M.; Li, Y.; Jagtap, P.; Mizushima, N.; Cuny, G.D.; Mitchison, T.J.; Moskowitz, M.A.; Yuan, J. Chemical inhibitor of nonapoptotic cell death with therapeutic potential for ischemic brain injury. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2005, 1, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, C.; Baburamani, A.A.; Kichev, A.; Hagberg, H. Oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in the development of neonatal hypoxic-ischaemic brain injury. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2017, 45, 1067–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Valdez, R.; Martin, L.J.; Flock, D.L.; Northington, F.J. Necrostatin-1 attenuates mitochondrial dysfunction in neurons and astrocytes following neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. Neuroscience 2012, 219, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lear, B.A.; Lear, C.A.; Dhillon, S.K.; King, V.J.; Dean, J.M.; Davidson, J.O.; Gunn, A.J.; Bennet, L. Delayed necrostatin-1s infusion attenuates cystic white matter injury in preterm fetal sheep. Neurotherapeutics 2025, e00775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Guan, X.; Guo, W.; Lu, B. Therapeutic potential of a TrkB agonistic antibody for ischemic brain injury. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 127, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Xiong, X. Serum Level of RIPK1/3 Correlated With the Prognosis in ICU Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2024, 12, e70085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.D.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, S.J.; Guo, M. Alteration of serum MLKL Levels and their association with severity and clinical outcomes in human severe traumatic brain injury: A orospective cohort study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2024, 17, 5069–5084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; He, S.; Chen, S.; Liao, D.; Wang, L.; Yan, J.; Liu, W.; Lei, X.; et al. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3 kinase. Cell 2012, 148, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galluzzi, L.; Vitale, I.; Aaronson, S.A.; Abrams, J.M.; Adam, D.; Agostinis, P.; Alnemri, E.S.; Altucci, L.; Amelio, I.; Andrews, D.W.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 486–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.Q.; Pang, R.; Robertson, N.J.; Dean, J.M.; Bennet, L.; Davidson, J.O.; Gunn, A.J. The advantages and limitations of animal models for understanding acute neonatal brain injury. Semin. Perinatol. 2025, 41, 152129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maj, H.; Mallard, C.; Eklind, S.; Gustafson-Brywe, K.; Hagberg, H. Global gene expression in the immature brain after hypoxia-ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2004, 24, 1317–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savard, A.; Lavoie, K.; Brochu, M.E.; Grbic, D.; Lepage, M.; Gris, D.; Sebire, G. Involvement of neuronal IL-1beta in acquired brain lesions in a rat model of neonatal encephalopathy. J. Neuroinflammation 2013, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savard, A.; Brochu, M.E.; Chevin, M.; Guiraut, C.; Grbic, D.; Sebire, G. Neuronal self-injury mediated by IL-1beta and MMP-9 in a cerebral palsy model of severe neonatal encephalopathy induced by immune activation plus hypoxia-ischemia. J. Neuroinflammation 2015, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, M.; Shibata, M.; Tadakoshi, M.; Gotoh, K.; Komatsu, M.; Waguri, S.; Kawahara, N.; Kuida, K.; Nagata, S.; Kominami, E.; et al. Inhibition of autophagy prevents hippocampal pyramidal neuron death after hypoxic-ischemic injury. Am. J. Pathol. 2008, 172, 454–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginet, V.; Puyal, J.; Clarke, P.G.; Truttmann, A.C. Enhancement of autophagic flux after neonatal cerebral hypoxia-ischemia and its region-specific relationship to apoptotic mechanisms. Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 175, 1962–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginet, V.; Pittet, M.P.; Rummel, C.; Osterheld, M.C.; Meuli, R.; Clarke, P.G.; Puyal, J.; Truttmann, A.C. Dying neurons in thalamus of asphyxiated term newborns and rats are autophagic. Ann. Neurol. 2014, 76, 695–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Q.; Harris, V.A.; Kumar, S.; Mansour, H.M.; Black, S.M. Autophagy in neonatal hypoxia ischemic brain is associated with oxidative stress. Redox Biology 2015, 6, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, D.; Sun, D.; Wang, X.; Yi, L.; Kulikowicz, E.; Reyes, M.; Zhu, J.; Yang, Z.J.; Jiang, W.; Koehler, R.C. Impaired autophagosome clearance contributes to neuronal death in a piglet model of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shoji-Kawata, S.; Sumpter, R.M., Jr.; Wei, Y.; Ginet, V.; Zhang, L.; Posner, B.; Tran, K.A.; Green, D.R.; Xavier, R.J.; et al. Autosis is a Na+,K+-ATPase-regulated form of cell death triggered by autophagy-inducing peptides, starvation, and hypoxia-ischemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 20364–20371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depierre, P.; Ginet, V.; Truttmann, A.C.; Puyal, J. Neuronal autosis is Na/K-ATPase alpha 3-dependent and involved in hypoxic-ischemic neuronal death. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, M.E.; Han, B.H.; Choi, J.; Knudson, C.M.; Korsmeyer, S.J.; Parsadanian, M.; Holtzman, D.M. BAX contributes to apoptotic-like death following neonatal hypoxia-ischemia: Evidence for distinct apoptosis pathways. Mol. Med. 2001, 7, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levison, S.W.; Rocha-Ferreira, E.; Kim, B.H.; Hagberg, H.; Fleiss, B.; Gressens, P.; Dobrowolski, R. Mechanisms of Tertiary Neurodegeneration after Neonatal Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Damage. Pediatr. Med. 2022, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitale, I.; Pietrocola, F.; Guilbaud, E.; Aaronson, S.A.; Abrams, J.M.; Adam, D.; Agostini, M.; Agostinis, P.; Alnemri, E.S.; Altucci, L.; et al. Apoptotic cell death in disease-Current understanding of the NCCD 2023. Cell Death Differ. 2023, 30, 1097–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Zhu, X.; Sun, S.; Yang, W.; Liu, S.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Li, J.; Shen, T.; Hei, M. Inhibition of TLR4 prevents hippocampal hypoxic-ischemic injury by regulating ferroptosis in neonatal rats. Exp. Neurol. 2021, 345, 113828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Zhang, T.L.; Zheng, J.Y.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Lin, Z.L.; Fu, X.Q. Ferroptosis is Involved in Hypoxic-ischemic Brain Damage in Neonatal Rats. Neuroscience 2022, 487, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Wei, T.; Xiao, P.; Ye, Q.; Li, Y.; Lu, W.; Huang, J. Multimodal MRI Techniques Reveal Brain Iron Deposition and Glymphatic Dysfunction in newborns with Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy. Acad. Radiol. 2025, 32, 6227–6237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troncoso, M.; Bannoud, N.; Carvelli, L.; Asensio, J.; Seltzer, A.; Sosa, M.A. Hypoxia-ischemia alters distribution of lysosomal proteins in rat cortex and hippocampus. Biol. Open 2018, 7, bio036723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northington, F.J.; Zelaya, M.E.; O’Riordan, D.P.; Blomgren, K.; Flock, D.L.; Hagberg, H.; Ferriero, D.M.; Martin, L.J. Failure to complete apoptosis following neonatal hypoxia-ischemia manifests as “continuum” phenotype of cell death and occurs with multiple manifestations of mitochondrial dysfunction in rodent forebrain. Neuroscience 2007, 149, 822–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Chavez-Valdez, R.; Flock, D.L.; Avaritt, O.; Saraswati, M.; Robertson, C.; Martin, L.J.; Northington, F.J. An Inhibitor of the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore Lacks Therapeutic Efficacy Following Neonatal Hypoxia Ischemia in Mice. Neuroscience 2019, 406, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilton, G.D.; Nunez, J.L.; Bambrick, L.; Thompson, S.M.; McCarthy, M.M. Glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity in neonatal hippocampal neurons is mediated by mGluR-induced release of Ca from intracellular stores and is prevented by estradiol. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006, 24, 3008–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, R.S.; Lee, T.F.; Liu, J.Q.; Chaudhary, H.; Brocks, D.R.; Bigam, D.L.; Cheung, P.Y. Cyclosporine treatment reduces oxygen free radical generation and oxidative stress in the brain of hypoxia-reoxygenated newborn piglets. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, M.W.; Santos, P.; Kulikowicz, E.; Koehler, R.C.; Lee, J.K.; Martin, L.J. Targeting the mitochondrial permeability transition pore for neuroprotection in a piglet model of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J. Neurosci. Res. 2021, 99, 1550–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, A.S.; O’Brien, X.M.; Laforce-Nesbitt, S.S.; Parisi, V.E.; Hirakawa, M.P.; Bliss, J.M.; Reichner, J.S. NETosis in neonates: Evidence of a reactive oxygen species-independent pathway in response to fungal challenge. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 213, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernis, M.E.; Zweyer, M.; Maes, E.; Schleehuber, Y.; Sabir, H. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Release following Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Injury in Newborn Rats Treated with Therapeutic Hypothermia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Wang, X.; Huang, Z.; Qiu, L.; Xu, F.; Vahsen, N.; Nilsson, M.; Eriksson, P.S.; Hagberg, H.; Culmsee, C.; et al. Apoptosis-inducing factor is a major contributor to neuronal loss induced by neonatal cerebral hypoxia-ischemia. Cell Death Diff. 2007, 14, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joly, L.M.; Benjelloun, N.; Plotkine, M.; Charriaut-Marlangue, C. Distribution of Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation and cell death after cerebral ischemia in the neonatal rat. Pediatr. Res. 2003, 53, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klofers, M.; Kohaut, J.; Bendix, I.; Herz, J.; Boos, V.; Felderhoff-Muser, U.; Dzietko, M. Effects of poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase-1 inhibition in a neonatal rodent model of hypoxic-ischemic injury. Biomed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 2924848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sha, S.; Jin, N.; Zhou, R.; Ruan, Y.; Ouyang, Y. The Activation of PKM2 Induces Pyroptosis in Hippocampal Neurons via the NLRP3/Caspase-1/GSDMD Pathway in Neonatal Rats With Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Injury. Brain Behav. 2024, 14, e70108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, K.; Zhu, X.; Yu, J.; Chen, L.; Liu, S.; Yan, M.; Yang, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; et al. Effects of HMGB1/RAGE/cathespin B inhibitors on alleviating hippocampal injury by regulating microglial pyroptosis and caspase activation in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain damage. J. Neurochem. 2023, 167, 410–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Sun, B.; Lu, X.X.; Liu, Y.L.; Li, M.; Xu, L.X.; Feng, C.X.; Ding, X.; Feng, X. The role of microglia mediated pyroptosis in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain damage. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 521, 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samaiya, P.K.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Kumar, A. Mitochondrial dysfunction in perinatal asphyxia: Role in pathogenesis and potential therapeutic interventions. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2021, 476, 4421–4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartings, J.A.; Shuttleworth, C.W.; Kirov, S.A.; Ayata, C.; Hinzman, J.M.; Foreman, B.; Andrew, R.D.; Boutelle, M.G.; Brennan, K.C.; Carlson, A.P.; et al. The continuum of spreading depolarizations in acute cortical lesion development: Examining Leao’s legacy. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2017, 37, 1571–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szydlowska, K.; Tymianski, M. Calcium, ischemia and excitotoxicity. Cell Calcium 2010, 47, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drury, P.P.; Bennet, L.; Booth, L.C.; Davidson, J.O.; Wassink, G.; Gunn, A.J. Maturation of the mitochondrial redox response to profound asphyxia in fetal sheep. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Orrenius, S.; Zhivotovsky, B.; Nicotera, P. Regulation of cell death: The calcium-apoptosis link. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 4, 552–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, V.L.; Kizushi, V.M.; Huang, P.L.; Snyder, S.H.; Dawson, T.M. Resistance to neurotoxicity in cortical cultures from neuronal nitric oxide synthase-deficient mice. J. Neurosci. 1996, 16, 2479–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drury, P.P.; Davidson, J.O.; van den Heuij, L.G.; Tan, S.; Silverman, R.B.; Ji, H.; Blood, A.B.; Fraser, M.; Bennet, L.; Gunn, A.J. Partial neuroprotection by nNOS inhibition during profound asphyxia in preterm fetal sheep. Exp. Neurol. 2013, 250, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rubbo, H.; Radi, R.; Trujillo, M.; Telleri, R.; Kalyanaraman, B.; Barnes, S.; Kirk, M.; Freeman, B.A. Nitric oxide regulation of superoxide and peroxynitrite-dependent lipid peroxidation. Formation of novel nitrogen-containing oxidized lipid derivatives. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 26066–26075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northington, F.J.; Ferriero, D.M.; Flock, D.L.; Martin, L.J. Delayed neurodegeneration in neonatal rat thalamus after hypoxia-ischemia is apoptosis. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 1931–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.E.; Gunn, A.J.; Mallard, C.; Gluckman, P.D. Outcome after ischemia in the developing sheep brain: An electroencephalographic and histological study. Ann. Neurol. 1992, 31, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunn, A.J.; Gunn, T.R. Changes in risk factors for hypoxic-ischaemic seizures in term infants. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1997, 37, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennet, L.; Roelfsema, V.; Pathipati, P.; Quaedackers, J.S.; Gunn, A.J. Relationship between evolving epileptiform activity and delayed loss of mitochondrial activity after asphyxia measured by near-infrared spectroscopy in preterm fetal sheep. J. Physiol. 2006, 572, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, S.K.; Gunn, E.R.; Lear, B.A.; King, V.J.; Lear, C.A.; Wassink, G.; Davidson, J.O.; Bennet, L.; Gunn, A.J. Cerebral Oxygenation and Metabolism After Hypoxia-Ischemia. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 925951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, C.; Leaw, B.; Mallard, C.; Nair, S.; Jinnai, M.; Hagberg, H. Cell Death in the Developing Brain after Hypoxia-Ischemia. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, C.; Hagberg, H. Role of mitochondria in apoptotic and necroptotic cell death in the developing brain. Clin. Chim. Acta 2015, 451, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portera-Cailliau, C.; Price, D.L.; Martin, L.J. Non-NMDA and NMDA receptor-mediated excitotoxic neuronal deaths in adult brain are morphologically distinct: Further evidence for an apoptosis-necrosis continuum. J. Comp. Neurol. 1997, 378, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Valdez, R.; Martin, L.J.; Northington, F.J. Programmed Necrosis: A Prominent Mechanism of Cell Death following Neonatal Brain Injury. Neurol. Res. Int. 2012, 2012, 257563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northington, F.J.; Chavez-Valdez, R.; Graham, E.M.; Razdan, S.; Gauda, E.B.; Martin, L.J. Necrostatin decreases oxidative damage, inflammation, and injury after neonatal HI. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2011, 31, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truttmann, A.C.; Ginet, V.; Puyal, J. Current Evidence on Cell Death in Preterm Brain Injury in Human and Preclinical Models. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ness, J.K.; Romanko, M.J.; Rothstein, R.P.; Wood, T.L.; Levison, S.W. Perinatal hypoxia-ischemia induces apoptotic and excitotoxic death of periventricular white matter oligodendrocyte progenitors. Dev. Neurosci. 2001, 23, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkerth, R.D. Neuropathologic substrate of cerebral palsy. J. Child Neurol. 2005, 20, 940–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannucci, S.J.; Seaman, L.B.; Brucklacher, R.M.; Vannucci, R.C. Glucose transport in developing rat brain: Glucose transporter proteins, rate constants and cerebral glucose utilization. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1994, 140, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, R.E. Fetal Asphyxia Due to Umbilical-Cord Compression—Metabolic and Brain Pathologic Consequences. Biol. Neonate 1975, 26, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carloni, S.; Perrone, S.; Buonocore, G.; Longini, M.; Proietti, F.; Balduini, W. Melatonin protects from the long-term consequences of a neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in rats. J. Pineal Res. 2008, 44, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Back, S.A.; Han, B.H.; Luo, N.L.; Chricton, C.A.; Xanthoudakis, S.; Tam, J.; Arvin, K.L.; Holtzman, D.M. Selective vulnerability of late oligodendrocyte progenitors to hypoxia-ischemia. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagen, M.W.; Riddle, A.; McClendon, E.; Gong, X.; Shaver, D.; Srivastava, T.; Dean, J.M.; Bai, J.Z.; Fowke, T.M.; Gunn, A.J.; et al. Role of recurrent hypoxia-ischemia in preterm white matter injury severity. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costigan, A.; Hollville, E.; Martin, S.J. Discriminating Between Apoptosis, Necrosis, Necroptosis, and Ferroptosis by Microscopy and Flow Cytometry. Curr. Protoc. 2023, 3, e951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddle, A.; Luo, N.L.; Manese, M.; Beardsley, D.J.; Green, L.; Rorvik, D.A.; Kelly, K.A.; Barlow, C.H.; Kelly, J.J.; Hohimer, A.R.; et al. Spatial heterogeneity in oligodendrocyte lineage maturation and not cerebral blood flow predicts fetal ovine periventricular white matter injury. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 3045–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuki, H.; Okuda, S. Arachidonic acid as a neurotoxic and neurotrophic substance. Prog. Neurobiol. 1995, 46, 607–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Dayani, L.; Rosenberg, P.A.; Li, J. RIP1 kinase mediates arachidonic acid-induced oxidative death of oligodendrocyte precursors. Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol. 2010, 2, 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Scaffidi, P.; Misteli, T.; Bianchi, M.E. Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature 2002, 418, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevin, M.; Chabrier, S.; Allard, M.J.; Sebire, G. Necroptosis blockade potentiates the neuroprotective effect of hypothermia in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, J.; Gao, H.M.; Xing, Y.H.; Lin, Z.; Li, H.J.; Wang, Y.Q. Necroptosis regulated proteins expression is an early prognostic biomarker in patient with sepsis: A prospective observational study. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 84066–84073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashaty, M.G.S.; Reilly, J.P.; Faust, H.E.; Forker, C.M.; Ittner, C.A.G.; Zhang, P.X.; Hotz, M.J.; Fitzgerald, D.; Yang, W.; Anderson, B.J.; et al. Plasma receptor interacting protein kinase-3 levels are associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome in sepsis and trauma: A cohort study. Crit. Care 2019, 23, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, H.; Im, Y.; Ko, R.E.; Lee, J.Y.; Park, J.; Jeon, K. Association of plasma level of high-mobility group box-1 with necroptosis and sepsis outcomes. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.; Yoo, H.; Lee, J.Y.; Park, J.; Jeon, K. Plasma Mitochondrial DNA and Necroptosis as Prognostic Indicators in Critically Ill Patients with Sepsis. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northington, F.J.; Ferriero, D.M.; Graham, E.M.; Traystman, R.J.; Martin, L.J. Early neurodegeneration after hypoxia-ischemia in neonatal rat is necrosis while delayed neuronal death is apoptosis. Neurobiol. Dis. 2001, 8, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northington, F.J.; Ferriero, D.M.; Martin, L.J. Neurodegeneration in the thalamus following neonatal hypoxia-ischemia is programmed cell death. Dev. Neurosci. 2001, 23, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, L.J.; Brambrink, A.M.; Price, A.C.; Kaiser, A.; Agnew, D.M.; Ichord, R.N.; Traystman, R.J. Neuronal death in newborn striatum after hypoxia-ischemia is necrosis and evolves with oxidative stress. Neurobiol. Dis. 2000, 7, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, H.; Qu, Y.; Li, S.; Zhao, F. miRNA-105 attenuates hypoxic-ischemic brain damage in neonatal rats by inhibiting apoptosis and necroptosis. Neurochem. Res. 2025, 50, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, R.D.; Bennet, L.; Naylor, A.; George, S.A.; Dean, J.M.; Gunn, A.J. Effect of cerebral hypothermia and asphyxia on the subventricular zone and white matter tracts in preterm fetal sheep. Brain Res. 2012, 1469, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellema, R.K.; Lima Passos, V.; Zwanenburg, A.; Ophelders, D.R.; De Munter, S.; Vanderlocht, J.; Germeraad, W.T.; Kuypers, E.; Collins, J.J.; Cleutjens, J.P.; et al. Cerebral inflammation and mobilization of the peripheral immune system following global hypoxia-ischemia in preterm sheep. J. Neuroinflammation 2013, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Shi, S.; Yang, C.; Jiang, W.; Luan, Z.; Liu, L.; Yao, R. Oligogenesis in the “oligovascular unit” involves PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling in hypoxic-ischemic neonatal mice. Brain Res. Bull. 2020, 155, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buser, J.R.; Maire, J.; Riddle, A.; Gong, X.; Nguyen, T.; Nelson, K.; Luo, N.L.; Ren, J.; Struve, J.; Sherman, L.S.; et al. Arrested preoligodendrocyte maturation contributes to myelination failure in premature infants. Ann. Neurol. 2012, 71, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, J.M.; McClendon, E.; Hansen, K.; Azimi-Zonooz, A.; Chen, K.; Riddle, A.; Gong, X.; Sharifnia, E.; Hagen, M.; Ahmad, T.; et al. Prenatal cerebral ischemia disrupts MRI-defined cortical microstructure through disturbances in neuronal arborization. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 168ra167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Back, S.A. White matter injury in the preterm infant: Pathology and mechanisms. Acta Neuropathol. 2017, 134, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, J.J.; Kinney, H.C.; Jensen, F.E.; Rosenberg, P.A. Reprint of “The developing oligodendrocyte: Key cellular target in brain injury in the premature infant”. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2011, 29, 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghotra, S.; Vincer, M.; Allen, V.M.; Khan, N. A population-based study of cystic white matter injury on ultrasound in very preterm infants born over two decades in Nova Scotia, Canada. J. Perinatol. 2019, 39, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Haastert, I.C.; Groenendaal, F.; Uiterwaal, C.S.; Termote, J.U.; van der Heide-Jalving, M.; Eijsermans, M.J.; Gorter, J.W.; Helders, P.J.; Jongmans, M.J.; de Vries, L.S. Decreasing incidence and severity of cerebral palsy in prematurely born children. J. Pediatr. 2011, 159, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Yue, Y.; Sun, H.; Cheng, P.; Xu, F.; Li, B.; Li, K.; Zhu, C. Clinical characteristics and long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes of leukomalacia in preterm infants and term infants: A cohort study. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2023, 15, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierrat, V.; Duquennoy, C.; van Haastert, I.C.; Ernst, M.; Guilley, N.; de Vries, L.S. Ultrasound diagnosis and neurodevelopmental outcome of localised and extensive cystic periventricular leucomalacia. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2001, 84, F151–F156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Shankaran, S.; Barks, J.; Do, B.T.; Laptook, A.R.; Das, A.; Ambalavanan, N.; Van Meurs, K.P.; Bell, E.F.; Sanchez, P.J.; et al. Outcome of Preterm Infants with Transient Cystic Periventricular Leukomalacia on Serial Cranial Imaging Up to Term Equivalent Age. J. Pediatr. 2018, 195, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, C.; Ding, A. Nonresolving inflammation. Cell 2010, 140, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardalan, M.; Svedin, P.; Baburamani, A.A.; Supramaniam, V.G.; Ek, J.; Hagberg, H.; Mallard, C. Dysmaturation of Somatostatin Interneurons Following Umbilical Cord Occlusion in Preterm Fetal Sheep. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geddes, R.; Vannucci, R.C.; Vannucci, S.J. Delayed cerebral atrophy following moderate hypoxia-ischemia in the immature rat. Dev. Neurosci. 2001, 23, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.P.; Wang, W.; Ma, Q.R.; Pan, X.L.; Zhai, H.L.; Wang, J.Y.; Han, Y.; Li, Y.H.; Wang, Y. Necrostatin-1s suppresses RIPK1-driven necroptosis and inflammation in periventricular leukomalacia neonatal mice. Neurochem. Res. 2024, 49, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lear, C.A.; Lear, B.A.; Davidson, J.O.; Sae-Jiw, J.; Lloyd, J.M.; Dhillon, S.K.; Gunn, A.J.; Bennet, L. Tumour necrosis factor blockade after asphyxia in foetal sheep ameliorates cystic white matter injury. Brain 2023, 146, 1453–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, S.; Yang, Y.; Mei, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhu, D.E.; Hoti, N.; Castanares, M.; Wu, M. Cleavage of RIP3 inactivates its caspase-independent apoptosis pathway by removal of kinase domain. Cell. Signal. 2007, 19, 2056–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofengeim, D.; Ito, Y.; Najafov, A.; Zhang, Y.; Shan, B.; DeWitt, J.P.; Ye, J.; Zhang, X.; Chang, A.; Vakifahmetoglu-Norberg, H.; et al. Activation of necroptosis in multiple sclerosis. Cell Rep. 2015, 10, 1836–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Amin, P.; Ofengeim, D. Necroptosis and RIPK1-mediated neuroinflammation in CNS diseases. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 20, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micheau, O.; Lens, S.; Gaide, O.; Alevizopoulos, K.; Tschopp, J. NF-kappaB signals induce the expression of c-FLIP. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001, 21, 5299–5305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinatizadeh, M.R.; Schock, B.; Chalbatani, G.M.; Zarandi, P.K.; Jalali, S.A.; Miri, S.R. The Nuclear Factor Kappa B (NF-kB) signaling in cancer development and immune diseases. Genes Dis. 2021, 8, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galinsky, R.; Lear, C.A.; Dean, J.M.; Wassink, G.; Dhillon, S.K.; Fraser, M.; Davidson, J.O.; Bennet, L.; Gunn, A.J. Complex interactions between hypoxia-ischemia and inflammation in preterm brain injury. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2018, 60, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.L.; Hagberg, H.; Naylor, A.S.; Mallard, C. Neonatal peripheral immune challenge activates microglia and inhibits neurogenesis in the developing murine hippocampus. Dev. Neurosci. 2014, 36, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehrmann, J.; Banati, R.B.; Wiessner, C.; Hossmann, K.A.; Kreutzberg, G.W. Reactive microglia in cerebral ischaemia: An early mediator of tissue damage? Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 1995, 21, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernis, M.E.; Schleehuber, Y.; Zweyer, M.; Maes, E.; Felderhoff-Muser, U.; Picard, D.; Sabir, H. Temporal Characterization of Microglia-Associated Pro- and Anti-Inflammatory Genes in a Neonatal Inflammation-Sensitized Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Injury Model. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 2479626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochfort, K.D.; Cummins, P.M. The blood-brain barrier endothelium: A target for pro-inflammatory cytokines. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2015, 43, 702–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornton, C.; Rousset, C.I.; Kichev, A.; Miyakuni, Y.; Vontell, R.; Baburamani, A.A.; Fleiss, B.; Gressens, P.; Hagberg, H. Molecular mechanisms of neonatal brain injury. Neurol. Res. Int. 2012, 2012, 506320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Nijhawan, D.; Budihardjo, I.; Srinivasula, S.M.; Ahmad, M.; Alnemri, E.S.; Wang, X. Cytochrome c and dATP-dependent formation of Apaf-1/caspase-9 complex initiates an apoptotic protease cascade. Cell 1997, 91, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, H.; Qi, C.; Zhang, K.; Liu, X.; Fei, L.; Chen, S.; Wang, M.; et al. RIPK3/MLKL-mediated neuronal necroptosis modulates the M1/M2 polarization of microglia/macrophages in the ischemic cortex. Cereb. Cortex 2018, 28, 2622–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Leak, R.K.; Shi, Y.; Suenaga, J.; Gao, Y.; Zheng, P.; Chen, J. Microglial and macrophage polarization-new prospects for brain repair. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2015, 11, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X. Microglia/macrophage polarization: Fantasy or evidence of functional diversity? J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2020, 40, S134–S136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellström Erkenstam, N.; Smith, P.L.; Fleiss, B.; Nair, S.; Svedin, P.; Wang, W.; Boström, M.; Gressens, P.; Hagberg, H.; Brown, K.L.; et al. Temporal Characterization of Microglia/Macrophage Phenotypes in a Mouse Model of Neonatal Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Injury. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, X.; Li, D.; Liu, N.; Xue, X.; Fu, J. Periventricular Microglia Polarization and Morphological Changes Accompany NLRP3 Inflammasome-Mediated Neuroinflammation after Hypoxic-Ischemic White Matter Damage in Premature Rats. J. Immunol. Res. 2023, 2023, 5149306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Q.; Idell, S.; Tang, H. M1 Macrophages Are More Susceptible to Necroptosis. J. Cell. Immunol. 2021, 3, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Azzopardi, D.; Strohm, B.; Linsell, L.; Hobson, A.; Juszczak, E.; Kurinczuk, J.J.; Brocklehurst, P.; Edwards, A.D. Implementation and conduct of therapeutic hypothermia for perinatal asphyxial encephalopathy in the UK--analysis of national data. PloS ONE 2012, 7, e38504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlman, J.M.; Wyllie, J.; Kattwinkel, J.; Atkins, D.L.; Chameides, L.; Goldsmith, J.P.; Guinsburg, R.; Hazinski, M.F.; Morley, C.; Richmond, S.; et al. Part 11: Neonatal resuscitation: 2010 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations. Circulation 2010, 122, S516–S538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunn, A.J.; Gunn, T.R.; Gunning, M.I.; Williams, C.E.; Gluckman, P.D. Neuroprotection with prolonged head cooling started before postischemic seizures in fetal sheep. Pediatrics 1998, 102, 1098–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunn, A.J.; Bennet, L.; Gunning, M.I.; Gluckman, P.D.; Gunn, T.R. Cerebral hypothermia is not neuroprotective when started after postischemic seizures in fetal sheep. Pediatr. Res. 1999, 46, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassink, G.; Davidson, J.O.; Lear, C.A.; Juul, S.E.; Northington, F.; Bennet, L.; Gunn, A.J. A working model for hypothermic neuroprotection. J. Physiol. 2018, 596, 5641–5654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmura, A.; Nakajima, W.; Ishida, A.; Yasuoka, N.; Kawamura, M.; Miura, S.; Takada, G. Prolonged hypothermia protects neonatal rat brain against hypoxic-ischemia by reducing both apoptosis and necrosis. Brain Dev. 2005, 27, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.D.; Yue, X.; Squier, M.V.; Thoresen, M.; Cady, E.B.; Penrice, J.; Cooper, C.E.; Wyatt, J.S.; Reynolds, E.O.; Mehmet, H. Specific inhibition of apoptosis after cerebral hypoxia-ischaemia by moderate post-insult hypothermia. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 217, 1193–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.J.; Lee, J.K.; Niedzwiecki, M.V.; Amrein Almira, A.; Javdan, C.; Chen, M.W.; Olberding, V.; Brown, S.M.; Park, D.; Yohannan, S.; et al. Hypothermia shifts neurodegeneration phenotype in neonatal human hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy but not in related piglet models: Possible relationship to toxic conformer and intrinsically disordered prion-like protein accumulation. Cells 2025, 14, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.J.; Chang, Q. DNA damage response and repair, DNA methylation, and cell death in human neurons and experimental animal neurons are different. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2018, 77, 636–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, T.; Blei, A.T.; Takamura, N.; Lin, T.; Guo, D.; Li, H.; O’Gorman, M.R.; Soriano, H.E. Hypothermia inhibits Fas-mediated apoptosis of primary mouse hepatocytes in culture. Cell Transplant. 2004, 13, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Kim, J.Y.; Koike, M.A.; Yoon, Y.J.; Tang, X.N.; Ma, H.; Lee, H.; Steinberg, G.K.; Lee, J.E.; Yenari, M.A. FasL shedding is reduced by hypothermia in experimental stroke. J. Neurochem. 2008, 106, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Guo, S.; Zhang, T.; Li, H. Hypothermia attenuates ischemia/reperfusion-induced endothelial cell apoptosis via alterations in apoptotic pathways and JNK signaling. FEBS Lett. 2009, 583, 2500–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.J.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Fan, B.; Li, G.Y. Neuroprotection by Therapeutic Hypothermia. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, D.D.; Rollins, L.G.; Perkel, J.K.; Wagner, C.L.; Katikaneni, L.P.; Bass, W.T.; Kaufman, D.A.; Horgan, M.J.; Languani, S.; Givelichian, L.; et al. Serum cytokines in a clinical trial of hypothermia for neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2012, 32, 1888–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalak, L.F.; Sanchez, P.J.; Adams-Huet, B.; Laptook, A.R.; Heyne, R.J.; Rosenfeld, C.R. Biomarkers for severity of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy and outcomes in newborns receiving hypothermia therapy. J. Pediatr. 2014, 164, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, C.J.; Youn, Y.A.; Yum, S.K.; Sung, I.K. Cytokine changes in newborns with therapeutic hypothermia after hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. J. Perinatol. 2016, 36, 1092–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha-Ferreira, E.; Kelen, D.; Faulkner, S.; Broad, K.D.; Chandrasekaran, M.; Kerenyi, A.; Kato, T.; Bainbridge, A.; Golay, X.; Sullivan, M.; et al. Systemic pro-inflammatory cytokine status following therapeutic hypothermia in a piglet hypoxia-ischemia model. J. Neuroinflammation 2017, 14, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinello, K.A.; Meehan, C.; Avdic-Belltheus, A.; Lingam, I.; Mutshiya, T.; Yang, Q.; Akin, M.A.; Price, D.; Sokolska, M.; Bainbridge, A. Hypothermia is not therapeutic in a neonatal piglet model of inflammation-sensitized hypoxia–ischemia. Pediatr. Res. 2022, 91, 1416–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lear, B.A.; McDouall, A.J.; Lear, O.J.; Dhillon, S.K.; Lear, C.A.; Northington, F.J.; Bennet, L.; Gunn, A.J. The Potential Clinical Relevance of Necrosis–Necroptosis Pathways for Hypoxic–Ischaemic Encephalopathy. Cells 2025, 14, 1984. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241984

Lear BA, McDouall AJ, Lear OJ, Dhillon SK, Lear CA, Northington FJ, Bennet L, Gunn AJ. The Potential Clinical Relevance of Necrosis–Necroptosis Pathways for Hypoxic–Ischaemic Encephalopathy. Cells. 2025; 14(24):1984. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241984

Chicago/Turabian StyleLear, Benjamin A., Alice J. McDouall, Olivia J. Lear, Simerdeep K. Dhillon, Christopher A. Lear, Frances J. Northington, Laura Bennet, and Alistair J. Gunn. 2025. "The Potential Clinical Relevance of Necrosis–Necroptosis Pathways for Hypoxic–Ischaemic Encephalopathy" Cells 14, no. 24: 1984. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241984

APA StyleLear, B. A., McDouall, A. J., Lear, O. J., Dhillon, S. K., Lear, C. A., Northington, F. J., Bennet, L., & Gunn, A. J. (2025). The Potential Clinical Relevance of Necrosis–Necroptosis Pathways for Hypoxic–Ischaemic Encephalopathy. Cells, 14(24), 1984. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241984