Next-Gen Stroke Models: The Promise of Assembloids and Organ-on-a-Chip Systems

Abstract

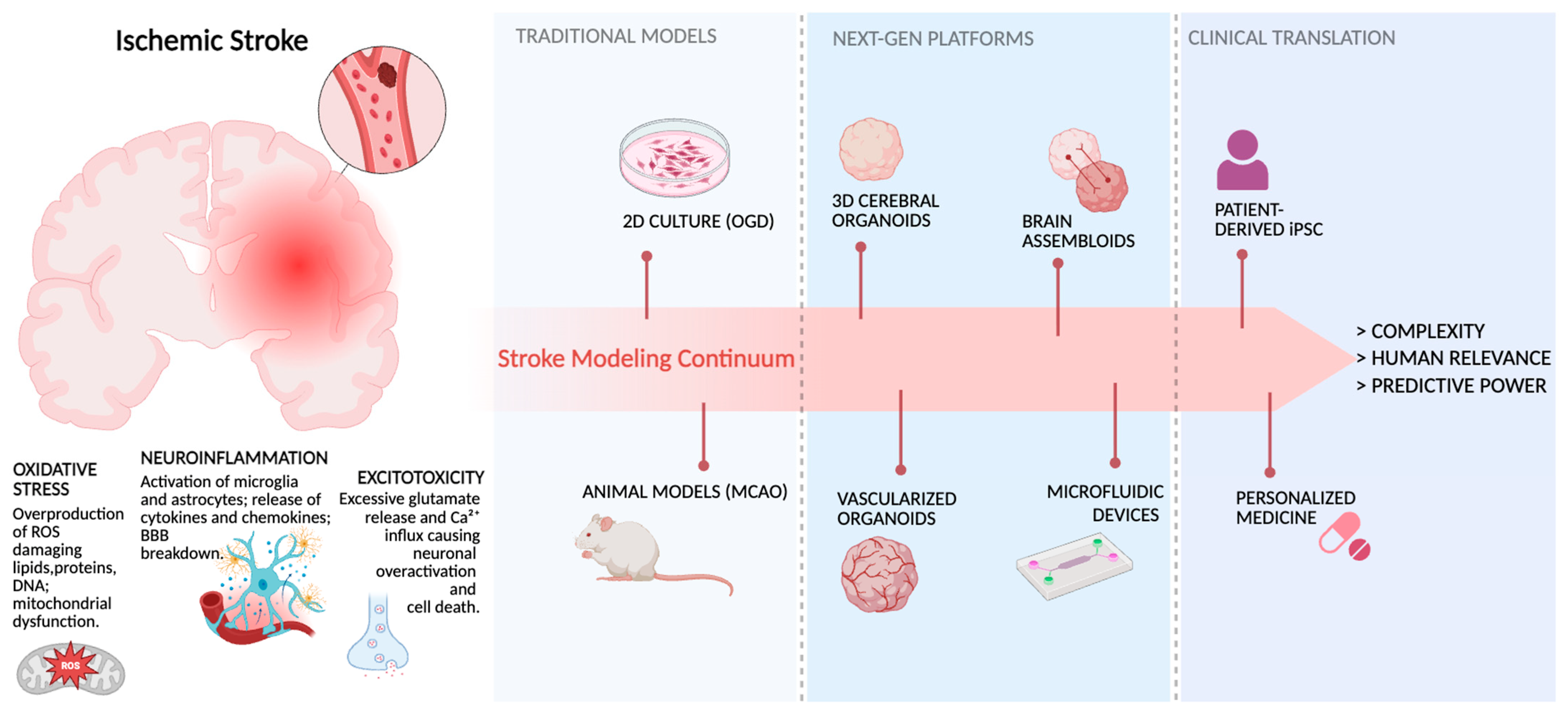

1. Introduction

2. When Models Fail: Limitations of 2D and Animal Models in Stroke Research

Bridging the Gap: The Unmet Needs in Stroke Modelling

3. Integrating Bioengineering Tools to Advance Brain Organoid Models

3.1. Microfluidic Devices

3.2. Organ-on-a-Chip Systems

3.3. 3D Bioprinting

3.4. Electrochemical Biosensors

3.5. Brain Assembloids and Multi-Regional Models

- Multi-regional assembloids, which combine organoids from different brain areas, such as dorsal cortex and ventral basal ganglia, or thalamus and cortex, to investigate phenomena like interneuron migration and thalamo-cortical circuit formation [50,51]. These assembloids can be generated from healthy human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), patient-derived or genetically modified hiPSCs, human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), or even primary tissue [48].

4. NVU-on-Chip: An Integrated Model for the Study of IS

Patient-Derived Models for Precision Medicine in Stroke

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NVU | neurovascular unit |

| OGD | oxygen and glucose deprivation |

| GOX/CAT | glucose oxidase and catalase system |

| ECM | extracellular matrix |

| SVZ | subventricular zone |

| iPSC | Patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cell |

| HUVECs | human umbilical vein endothelial cells |

| ECs | endothelial cells |

| OoC | Organ-on-a-chip |

| PDMS | Polydimethylsiloxane |

| TPP | two-photon polymerization |

| NSE | neuron-specific enolase |

| hESCs | human embryonic stem cells |

| PDOs | patient-derived organoids |

References

- GBD 2021 Stroke Risk Factor Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 973–1003. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, B.C.V.; De Silva, D.A.; Macleod, M.R.; Coutts, S.B.; Schwamm, L.H.; Davis, S.M.; Donnan, G.A. Ischaemic stroke. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2019, 5, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, B.; Wu, L.; Peng, Y. In vitro modelling of the neurovascular unit for ischemic stroke research: Emphasis on human cell applications and 3D model design. Exp. Neurol. 2024, 381, 114942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoshnam, S.E.; Winlow, W.; Farzaneh, M.; Farbood, Y.; Moghaddam, H.F. Pathogenic mechanisms following ischemic stroke. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 38, 1167–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardozzi, G.; Castelli, V.; Giorgi, C.; Cimini, A.; d’Angelo, M. Neuroinflammation strokes the brain: A double-edged sword in ischemic stroke. Neural Regen. Res. 2025, 21, 1715–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haupt, M.; Gerner, S.T.; Bähr, M.; Doeppner, T.R. Quest for Quality in Translational Stroke Research—A New Dawn for Neuroprotection? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Breedam, E.; Ponsaerts, P. Promising Strategies for the Development of Advanced In Vitro Models with High Predictive Power in Ischaemic Stroke Research. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, P.M.; Gavins, F.N.E. Modeling Ischemic Stroke In Vitro: The Status Quo and Future Perspectives. Stroke J. Cereb. Circ. 2016, 47, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.A.; Kharwar, A.; Dandekar, M.P. A Review on Preclinical Models of Ischemic Stroke: Insights Into the Pathomechanisms and New Treatment Strategies. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2022, 20, 1667–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koizumi, J.; Yoshida, Y.; Nakazawa, T.; Ooneda, G. Experimental studies of ischemic brain edema. Nosotchu 1986, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longa, E.Z.; Weinstein, P.R.; Carlson, S.; Cummins, R. Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke 1989, 20, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.-S.; Jin, H.; Sun, X.; Huang, S.; Zhang, F.-L.; Guo, Z.-N.; Yang, Y. Free Radical Damage in Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury: An Obstacle in Acute Ischemic Stroke after Revascularization Therapy. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 3804979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wei, X.; Kong, L.; Liu, X.; Cheng, L.; Yan, S.; Zhang, X.; Chen, L. NOD2 is Involved in the Inflammatory Response after Cerebral Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury and Triggers NADPH Oxidase 2-Derived Reactive Oxygen Species. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 11, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybachuk, O.; Kopach, O.; Krotov, V.; Voitenko, N.; Pivneva, T. Optimized Model of Cerebral Ischemia In situ for the Long-Lasting Assessment of Hippocampal Cell Death. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiede, L.M.; Cook, E.A.; Morsey, B.; Fox, H.S. Oxygen matters: Tissue culture oxygen levels affect mitochondrial function and structure as well as responses to HIV viroproteins. Cell Death Dis. 2011, 2, e246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Sun, X.; Xu, L.; Sun, R.; Ma, Z.; Deng, X.; Liu, B.; Fu, Q.; Qu, R.; Ma, S. Baicalin attenuates in vivo and in vitro hyperglycemia-exacerbated ischemia/reperfusion injury by regulating mitochondrial function in a manner dependent on AMPK. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 815, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centeno, E.G.Z.; Cimarosti, H.; Bithell, A. 2D versus 3D human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cultures for neurodegenerative disease modelling. Mol. Neurodegener. 2018, 13, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humpel, C. Organotypic brain slice cultures: A review. Neuroscience 2015, 305, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, M.A.; Renner, M.; Martin, C.-A.; Wenzel, D.; Bicknell, L.S.; Hurles, M.E.; Homfray, T.; Penninger, J.M.; Jackson, A.P.; Knoblich, J.A. Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature 2013, 501, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelava, I.; Lancaster, M.A. Dishing out mini-brains: Current progress and future prospects in brain organoid research. Dev. Biol. 2016, 420, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gattazzo, F.; Urciuolo, A.; Bonaldo, P. Extracellular matrix: A dynamic microenvironment for stem cell niche. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Gen. Subj. 2014, 1840, 2506–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Meng, T.; Yang, J.; Hu, N.; Zhao, H.; Tian, T. Three-dimensional in vitro tissue culture models of brain organoids. Exp. Neurol. 2021, 339, 113619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, B.; Choi, B.; Park, H.; Yoon, K.-J. Past, Present, and Future of Brain Organoid Technology. Mol. Cells 2019, 42, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, C.; Turrero Garcia, M.; Decimo, I.; Bifari, F.; Eelen, G.; Quaegebeur, A.; Boon, R.; Zhao, H.; Boeckx, B.; Chang, J.; et al. Relief of hypoxia by angiogenesis promotes neural stem cell differentiation by targeting glycolysis. EMBO J. 2016, 35, 924–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhrberg, C.; Bautch, V.L. Neurovascular development and links to disease. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013, 70, 1675–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Q.-J.; Wen, J.-Q.; Xu, X.-X.; Xie, H.-Q. Generation of vascularized brain organoids: Technology, applications, and prospects. Organoid Res. 2025, 1, 8162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wälchli, T.; Bisschop, J.; Carmeliet, P.; Zadeh, G.; Monnier, P.P.; De Bock, K.; Radovanovic, I. Shaping the brain vasculature in development and disease in the single-cell era. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2023, 24, 271–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, M.T.; Pollock, K.M.; Rose, M.D.; Cary, W.A.; Stewart, H.R.; Zhou, P.; Nolta, J.A.; Waldau, B. Generation of human vascularized brain organoids. Neuroreport 2018, 29, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dao, L.; You, Z.; Lu, L.; Xu, T.; Sarkar, A.K.; Zhu, H.; Liu, M.; Calandrelli, R.; Yoshida, G.; Lin, P.; et al. Modeling blood-brain barrier formation and cerebral cavernous malformations in human PSC-derived organoids. Cell Stem Cell 2024, 31, 818–833.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Sun, L.; Wang, M.; Liu, J.; Zhong, S.; Li, R.; Li, P.; Guo, L.; Fang, A.; Chen, R.; et al. Vascularized human cortical organoids (vOrganoids) model cortical development in vivo. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cakir, B.; Xiang, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Kural, M.H.; Parent, M.; Kang, Y.-J.; Chapeton, K.; Patterson, B.; Yuan, Y.; He, C.-S.; et al. Development of human brain organoids with functional vascular-like system. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 1169–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, O.; Jin, Y.B.; Kim, J.; Lee, M.-O. Blood vessel formation in cerebral organoids formed from human embryonic stem cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 521, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wan, Z.; Kamm, R.D. Vascularized organoids on a chip: Strategies for engineering organoids with functional vasculature. Lab. Chip 2021, 21, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, F.; Qu, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhong, R.; Luo, Y. Organ-on-a-Chip: New Platform for Biological Analysis. Anal. Chem. Insights 2015, 10, ACI.S28905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paloschi, V.; Sabater-Lleal, M.; Middelkamp, H.; Vivas, A.; Johansson, S.; van der Meer, A.; Tenje, M.; Maegdefessel, L. Organ-on-a-chip technology: A novel approach to investigate cardiovascular diseases. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, 2742–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakeri, A.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Landau, S.; Perera, K.; Lee, J.; Radisic, M. Engineering Organ-on-a-Chip Systems for Vascular Diseases. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2023, 43, 2241–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denecke, K.M.; McBain, C.A.; Hermes, B.G.; Teertam, S.K.; Farooqui, M.; Virumbrales-Muñoz, M.; Panackal, J.; Beebe, D.J.; Famakin, B.; Ayuso, J.M. Microfluidic Model to Evaluate Astrocyte Activation in Penumbral Region following Ischemic Stroke. Cells 2022, 11, 2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.; Brady, E.; Zheng, Y.; Moore, E.; Stevens, K.R. Engineering the multiscale complexity of vascular networks. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2022, 7, 702–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.-H.; Yun Bae, C.; Kwon, S.; Park, J.-K. User-friendly 3D bioassays with cell-containing hydrogel modules: Narrowing the gap between microfluidic bioassays and clinical end-users’ needs. Lab. Chip 2015, 15, 2379–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhou, C.; Lu, K.; Liu, Y.; Xuan, L.; Wang, X. Organoid-on-a-chip: Current challenges, trends, and future scope toward medicine. Biomicrofluidics 2023, 17, 051505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukelis, K.; Koutsomarkos, N.; Mikos, A.G.; Chatzinikolaidou, M. Advances in 3D bioprinting for regenerative medicine applications. Regen. Biomater. 2024, 11, rbae033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Yang, X.; Ma, Z.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Yang, H.; Qiang, L.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Y.; et al. Developments and Opportunities for 3D Bioprinted Organoids. Int. J. Bioprinting 2021, 7, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Ding, H.; Wu, S.; Xiong, N.; Hong, Y.; Zhu, W.; Chen, X.; Han, X.; Tao, M.; Wang, Y.; et al. Artificial Meshed Vessel-Induced Dimensional Breaking Growth of Human Brain Organoids and Multiregional Assembloids. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 26201–26214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Cong, L.; Cong, X. Patient-Derived Organoids in Precision Medicine: Drug Screening, Organoid-on-a-Chip and Living Organoid Biobank. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 762184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, E.; Palma, C.; Vesentini, S.; Occhetta, P.; Rasponi, M. Integrating Biosensors in Organs-on-Chip Devices: A Perspective on Current Strategies to Monitor Microphysiological Systems. Biosensors 2020, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu Chen, C.; Wang, E.; Lee, T.-H.; Huang, C.-C.; Tai, C.-S.; Lin, Y.-R.; Chen, W.-L. Point-of-Care NSE Biosensor for Objective Assessment of Stroke Risk. Biosensors 2025, 15, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajongbolo, A.O.; Langhans, S.A. Brain Organoids and Assembloids—From Disease Modeling to Drug Discovery. Cells 2025, 14, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanton, S.; Paşca, S.P. Human assembloids. Development 2022, 149, dev201120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pașca, S.P.; Arlotta, P.; Bateup, H.S.; Camp, J.G.; Cappello, S.; Gage, F.H.; Knoblich, J.A.; Kriegstein, A.R.; Lancaster, M.A.; Ming, G.-L.; et al. A nomenclature consensus for nervous system organoids and assembloids. Nature 2022, 609, 907–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagley, J.A.; Reumann, D.; Bian, S.; Lévi-Strauss, J.; Knoblich, J.A. Fused cerebral organoids model interactions between brain regions. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Patterson, B.; Kang, Y.-J.; Govindaiah, G.; Roselaar, N.; Cakir, B.; Kim, K.-Y.; Lombroso, A.P.; Hwang, S.-M.; et al. Fusion of Regionally Specified hPSC-Derived Organoids Models Human Brain Development and Interneuron Migration. Cell Stem Cell 2017, 21, 383–398.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, Y.; Li, M.-Y.; Birey, F.; Ikeda, K.; Revah, O.; Thete, M.V.; Park, J.-Y.; Puno, A.; Lee, S.H.; Porteus, M.H.; et al. Generation of human striatal organoids and cortico-striatal assembloids from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 1421–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birey, F.; Andersen, J.; Makinson, C.D.; Islam, S.; Wei, W.; Huber, N.; Fan, H.C.; Metzler, K.R.C.; Panagiotakos, G.; Thom, N.; et al. Assembly of functionally integrated human forebrain spheroids. Nature 2017, 545, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Clevers, H.; Shen, X. Promises and Challenges of Organoid-Guided Precision Medicine. Med 2021, 2, 1011–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrestizala-Arenaza, N.; Cerchio, S.; Cavaliere, F.; Magliaro, C. Limitations of human brain organoids to study neurodegenerative diseases: A manual to survive. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1419526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, M.; Grant, G.A.; Lee, W. The neurovascular unit-on-a-chip: Modeling ischemic stroke to stem cell therapy. Neural Regen. Res. 2023, 19, 1431–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Xiong, X.; Zhang, L.; Shen, J. Neurovascular Unit: A critical role in ischemic stroke. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2021, 27, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolden, C.T.; Skibber, M.A.; Olson, S.D.; Zamorano Rojas, M.; Milewicz, S.; Gill, B.S.; Cox, C.S. Validation and characterization of a novel blood–brain barrier platform for investigating traumatic brain injury. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, R.; Kim, H. Characterization of a microfluidic in vitro model of the blood-brain barrier (μBBB). Lab. Chip 2012, 12, 1784–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatine, G.D.; Barrile, R.; Workman, M.J.; Sances, S.; Barriga, B.K.; Rahnama, M.; Barthakur, S.; Kasendra, M.; Lucchesi, C.; Kerns, J.; et al. Human iPSC-Derived Blood-Brain Barrier Chips Enable Disease Modeling and Personalized Medicine Applications. Cell Stem Cell 2019, 24, 995–1005.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z.; Park, J.; Kim, K.-M.; Jin, H.-J.; Wu, H.; Rajadas, J.; Kim, D.-H.; Steinberg, G.K.; Lee, W. A neurovascular-unit-on-a-chip for the evaluation of the restorative potential of stem cell therapies for ischaemic stroke. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 5, 847–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Wu, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Su, J. AI-enabled organoids: Construction, analysis, and application. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 31, 525–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Kowalczewski, A.; Vu, D.; Liu, X.; Salekin, A.; Yang, H.; Ma, Z. Organoid intelligence: Integration of organoid technology and artificial intelligence in the new era of in vitro models. Med. Nov. Technol. Devices 2024, 21, 100276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chang, C.; Wang, R.; Li, X.; Bao, X. The advantages of multi-level omics research on stem cell-based therapies for ischemic stroke. Neural Regen. Res. 2023, 19, 1998–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Khutsishvili, D.; Tang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Cai, Y.; Dai, X.; Ma, S. Bridging the organoid translational gap: Integrating standardization and micropatterning for drug screening in clinical and pharmaceutical medicine. Life Med. 2024, 3, lnae016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model Type | Biological Complexity | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations | Stroke-Relevant Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D cell culture | ★✩✩✩ (low) | Flat monolayers defined and customizable cellular composition, high experimental throughput. | Easy to handle, cost- efficient, reproducible, suitable for mechanistic studies and drug screening. | Lack 3D architecture, limited cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions, low physiological relevance. | OGD/OGD-R assays, neuroprotection screening, oxidative stress and apoptosis pathways. |

| Brain organoids | ★★✩✩ (medium) | 3D self-organized structures, early neurodevelopmental features, regional specification possible. | Human-specific architecture, recapitulate neurogenesis and cortical layer formation, long-term culture. | High variability, limited vascularization, restricted maturation, weak NVU representation. | Modeling developmental susceptibility to ischemia, cell-type specific responses, personalized hiPSC models. |

| Assembloids | ★★★✩ (medium high) | Fusion of region-specific organoids, long-range connectivity. | Mimic inter-regional communication, better network-level physiology. | Variability in fusion and connectivity, limited scalability, still non- vascularized | Studying propagation of ischemic stress between brain regions, circuit-level vulnerability. |

| Microfluidics-devices | ★★✩✩ (medium) | Microscale channels, controlled flow, gradients and microenvironment. | High precision, recreate shear stress, nutrient flow, O2/glucose gradients. | Require technical expertise, limited multicellular complexity. | Modeling perfusion deficits, OGD-R kinetics, real-time barrier assessment. |

| 3D Bioprinting | ★★✩✩ (medium) | Leyered, spatially controlled printing of cells + ECM biomaterials. | Tunable architecture, controlled cell orientation, reproducible geometry. | Complex protocols, limited maturation, ECM bioinks not fully brain-like. | Testing neuroprotective scaffolds, oxygen diffusion patterns, cell-specific survival. |

| Electrochemical biosensor | ★★★✩ (medium-high) | Real-time monitoring of metabolic and injury markers directly within model | High temporaly resolution non-desctructive measurements, integrates with OoC systems. | Tipically require custom engineering, may need calibration. | Tracking lactate, glucose, ROS, barrier integrity during OGD/R. |

| Nvu-on-a-chip | ★★★★ (high) | Spatially organized ECs, pericytes, astrocytes ± neurons; perfusable barrier. | Recreates BBB physiology, quantitative permeability readouts, dynamic monitoring. | Still simplified vs in vivo NVU, material-related constraints. | BBB breakdown, leukocyte trafficking, vascular inflammation, reperfusion injury. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lombardozzi, G.; Szebényi, K.; Giorgi, C.; Topi, S.; d’Angelo, M.; Castelli, V.; Cimini, A. Next-Gen Stroke Models: The Promise of Assembloids and Organ-on-a-Chip Systems. Cells 2025, 14, 1986. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241986

Lombardozzi G, Szebényi K, Giorgi C, Topi S, d’Angelo M, Castelli V, Cimini A. Next-Gen Stroke Models: The Promise of Assembloids and Organ-on-a-Chip Systems. Cells. 2025; 14(24):1986. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241986

Chicago/Turabian StyleLombardozzi, Giorgia, Kornélia Szebényi, Chiara Giorgi, Skender Topi, Michele d’Angelo, Vanessa Castelli, and Annamaria Cimini. 2025. "Next-Gen Stroke Models: The Promise of Assembloids and Organ-on-a-Chip Systems" Cells 14, no. 24: 1986. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241986

APA StyleLombardozzi, G., Szebényi, K., Giorgi, C., Topi, S., d’Angelo, M., Castelli, V., & Cimini, A. (2025). Next-Gen Stroke Models: The Promise of Assembloids and Organ-on-a-Chip Systems. Cells, 14(24), 1986. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241986