Astrocyte-Mediated Plasticity: Multi-Scale Mechanisms Linking Synaptic Dynamics to Learning and Memory

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

3. Classical Core Mechanisms of Astrocyte-Mediated Synaptic Plasticity

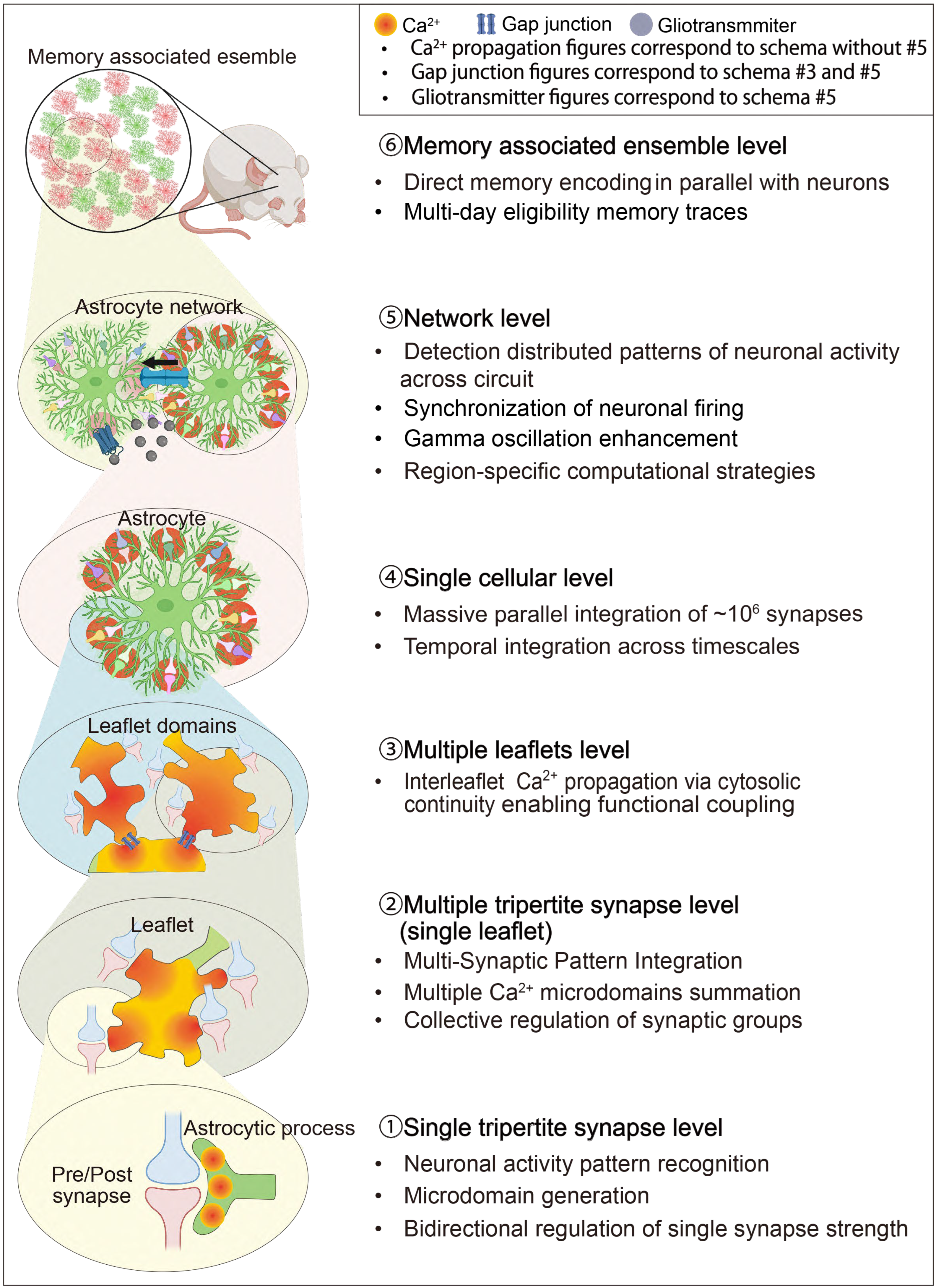

4. Beyond the Classical Tripartite Model

4.1. Microdomains and Leaflet Domains: Hierarchical Units of Astrocytic Integration

4.1.1. Microdomains: Synapse-Specific Read–Write Units

4.1.2. Leaflet Domains: Structural Basis for Multi-Synaptic Integration

4.2. Astrocytes as Network Coordinators

4.2.1. Network-Level Coordination

4.2.2. Temporal Integration and Metaplasticity

4.2.3. Region-Specific Coordination and Adaptive Plasticity

4.2.4. Adhesion-Based Mechanisms for Astrocytic Control of Neural Circuits

4.3. Astrocyte Ensembles in Memory Regulate Memory Processing

4.3.1. Early Evidence for Astrocytic Contributions to Memory

4.3.2. Astrocytic Ensembles as Memory Engram Components

4.4. Astrocytic Computational Frameworks and the Neuron–Astrocyte Associative Memory (NAAM) Model

5. Future Directions

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Astrocytes participate in memory formation through diverse mechanisms, including parallel processing and integration of inputs from multiple synapses, the structural and functional regulation of synapses, circuit-level neuronal regulation and the encoding of memory within astrocyte ensembles. These processes operate hierarchically across microdomains, multi-synaptic leaflets, single-cell territories, and network-level ensembles, enabling astrocytes to couple local plasticity with large-scale circuit adaptation.

- (2)

- Explaining the brain’s remarkable computational and mnemonic capabilities may require moving beyond neuron- and synapse-centric views to include astrocytic dynamics, as increasingly supported by emerging experimental and computational frameworks. These models propose that slow, integrative calcium states within astrocytes could complement fast neuronal signaling by providing temporally extended, activity-silent forms of information storage. Incorporating astrocytes into memory theory may therefore help reconcile how the brain achieves high capacity, stability, and robustness with limited metabolic cost. The stability and robustness potentially conferred by such astrocytic memory codes along with possible metabolic efficiency gains remain theoretically compelling but require further experimental validation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bazargani, N.; Attwell, D. Astrocyte Calcium Signaling: The Third Wave. Nat. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covelo, A.; Araque, A. Neuronal Activity Determines Distinct Gliotransmitter Release from a Single Astrocyte. Elife 2018, 7, e32237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panatier, A.; Vallée, J.; Haber, M.; Murai, K.K.; Lacaille, J.-C.; Robitaille, R. Astrocytes Are Endogenous Regulators of Basal Transmission at Central Synapses. Cell 2011, 146, 785–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, O.; Casper, K.B.; Kubera, C.; Zhang, J.; Revilla-Sanchez, R.; Sul, J.-Y.; Takano, H.; Moss, S.J.; McCarthy, K.; Haydon, P.G. Astrocytic Purinergic Signaling Coordinates Synaptic Networks. Science 2005, 310, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volterra, A.; Meldolesi, J. Astrocytes, from Brain Glue to Communication Elements: The Revolution Continues. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005, 6, 626–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, R.; Nevian, T. Astrocyte Signaling Controls Spike Timing-Dependent Depression at Neocortical Synapses. Nat. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 746–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, M.; Perea, G.; Fernandez de Sevilla, D.; Gómez-Gonzalo, M.; Núñez, A.; Martín, E.D.; Araque, A. Astrocytes Mediate in Vivo Cholinergic-Induced Synaptic Plasticity. PLoS Biol. 2012, 10, e1001259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcón-Moya, R.; Pérez-Rodríguez, M.; Prius-Mengual, J.; Andrade-Talavera, Y.; Arroyo-García, L.E.; Pérez-Artés, R.; Mateos-Aparicio, P.; Guerra-Gomes, S.; Oliveira, J.F.; Flores, G.; et al. Astrocyte-Mediated Switch in Spike Timing-Dependent Plasticity during Hippocampal Development. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofuji, P.; Newman, E.A. Potassium Buffering in the Central Nervous System. Neuroscience 2004, 129, 1045–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy-Royal, C.; Dupuis, J.; Groc, L.; Oliet, S.H.R. Astroglial Glutamate Transporters in the Brain: Regulating Neurotransmitter Homeostasis and Synaptic Transmission. J. Neurosci. Res. 2017, 95, 2140–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, E.; Lengacher, S.; Dias, S.; Magistretti, P.J.; Finsterwald, C. Astrocytes as Key Regulators of Brain Energy Metabolism: New Therapeutic Perspectives. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 825816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, J.P.; Rusakov, D.A. The Nanoworld of the Tripartite Synapse: Insights from Super-Resolution Microscopy. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2017, 11, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arizono, M.; Inavalli, V.V.G.K.; Panatier, A.; Pfeiffer, T.; Angibaud, J.; Levet, F.; Ter Veer, M.J.T.; Stobart, J.; Bellocchio, L.; Mikoshiba, K.; et al. Structural Basis of Astrocytic Ca2+ Signals at Tripartite Synapses. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benoit, L.; Hristovska, I.; Liaudet, N.; Jouneau, P.-H.; Fertin, A.; de Ceglia, R.; Litvin, D.; Di Castro, M.A.; Jevtic, M.; Zalachoras, I.; et al. Astrocytes Functionally Integrate Multiple Synapses via Specialized Leaflet Domains. Cell 2025, 188, 6453–6472.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindocci, E.; Savtchouk, I.; Liaudet, N.; Becker, D.; Carriero, G.; Volterra, A. Three-Dimensional Ca2+ Imaging Advances Understanding of Astrocyte Biology. Science 2017, 356, eaai8185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stobart, J.L.; Ferrari, K.D.; Barrett, M.J.P.; Glück, C.; Stobart, M.J.; Zuend, M.; Weber, B. Cortical Circuit Activity Evokes Rapid Astrocyte Calcium Signals on a Similar Timescale to Neurons. Neuron 2018, 98, 726–735.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, M.R.; Kwon, W.; Woo, J.; Ko, Y.; Maleki, E.; Yu, K.; Murali, S.; Sardar, D.; Deneen, B. Learning-Associated Astrocyte Ensembles Regulate Memory Recall. Nature 2025, 637, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citri, A.; Malenka, R.C. Synaptic Plasticity: Multiple Forms, Functions, and Mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology 2008, 33, 18–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, J.C.; Grienberger, C. Synaptic Plasticity Forms and Functions. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2020, 43, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langille, J.J.; Brown, R.E. The Synaptic Theory of Memory: A Historical Survey and Reconciliation of Recent Opposition. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R.G.D.O. Hebb: The Organization of Behavior, Wiley: New York; 1949. Brain Res. Bull. 1999, 50, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos-Aparicio, P.; Rodríguez-Moreno, A. The Impact of Studying Brain Plasticity. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2019, 13, 66. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, S.J.; Grimwood, P.D.; Morris, R.G. Synaptic Plasticity and Memory: An Evaluation of the Hypothesis. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2000, 23, 649–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusi, S. Memory Capacity of Neural Network Models. In The Oxford Handbook of Human Memory, Two Volume Pack; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2024; pp. 740–764. ISBN 9780190917982. [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano, G. Homeostatic Synaptic Plasticity: Local and Global Mechanisms for Stabilizing Neuronal Function. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012, 4, a005736. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, W.C.; Jones, O.D.; Glanzman, D.L. Is Plasticity of Synapses the Mechanism of Long-Term Memory Storage? NPJ Sci. Learn. 2019, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; McLaughlin, D.W.; Peskin, C.S. A Biochemical Description of Postsynaptic Plasticity-with Timescales Ranging from Milliseconds to Seconds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2311709121. [Google Scholar]

- Bittner, K.C.; Milstein, A.D.; Grienberger, C.; Romani, S.; Magee, J.C. Behavioral Time Scale Synaptic Plasticity Underlies CA1 Place Fields. Science 2017, 357, 1033–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araque, A.; Parpura, V.; Sanzgiri, R.P.; Haydon, P.G. Tripartite Synapses: Glia, the Unacknowledged Partner. Trends Neurosci. 1999, 22, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea, G.; Navarrete, M.; Araque, A. Tripartite Synapses: Astrocytes Process and Control Synaptic Information. Trends Neurosci. 2009, 32, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porto-Pazos, A.B.; Veiguela, N.; Mesejo, P.; Navarrete, M.; Alvarellos, A.; Ibáñez, O.; Pazos, A.; Araque, A. Artificial Astrocytes Improve Neural Network Performance. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, R.; Santello, M.; Nevian, T. The Computational Power of Astrocyte Mediated Synaptic Plasticity. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.; Pan, L.; Liu, X. AstroNet: When Astrocyte Meets Artificial Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gordleeva, S.Y.; Tsybina, Y.A.; Krivonosov, M.I.; Ivanchenko, M.V.; Zaikin, A.A.; Kazantsev, V.B.; Gorban, A.N. Modeling Working Memory in a Spiking Neuron Network Accompanied by Astrocytes. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2021, 15, 631485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunusoglu, A.; Le, D.; Isik, M.; Dikmen, I.C.; Karadag, T. Neuromorphic Circuits with Spiking Astrocytes for Increased Energy Efficiency, Fault Tolerance, and Memory Capacitance. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarellos-González, A.; Pazos, A.; Porto-Pazos, A.B. Computational Models of Neuron-Astrocyte Interactions Lead to Improved Efficacy in the Performance of Neural Networks. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2012, 2012, 476324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho, L.; Contreras, M.; Allen, N.J. Glia as Sculptors of Synaptic Plasticity. Neurosci. Res. 2021, 167, 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, K.J.; Robitaille, R. Purinergic Modulation of Synaptic Signalling at the Neuromuscular Junction. Pflug. Arch. 2006, 452, 608–614. [Google Scholar]

- Pfrieger, F.W.; Barres, B.A. Synaptic Efficacy Enhanced by Glial Cells in Vitro. Science 1997, 277, 1684–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura, R.; Harris, K.M. Three-Dimensional Relationships between Hippocampal Synapses and Astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 1999, 19, 6897–6906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.I.; Ryan, M.A.; McNabb, M.C.; Kamasawa, N.; Scholl, B. Astrocyte Coverage of Excitatory Synapses Correlates to Measures of Synapse Structure and Function in Ferret Primary Visual Cortex. Glia 2024, 72, 1785–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genoud, C.; Quairiaux, C.; Steiner, P.; Hirling, H.; Welker, E.; Knott, G.W. Plasticity of Astrocytic Coverage and Glutamate Transporter Expression in Adult Mouse Cortex. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4, e343. [Google Scholar]

- Deemyad, T.; Lüthi, J.; Spruston, N. Astrocytes Integrate and Drive Action Potential Firing in Inhibitory Subnetworks. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kol, A.; Adamsky, A.; Groysman, M.; Kreisel, T.; London, M.; Goshen, I. Astrocytes Contribute to Remote Memory Formation by Modulating Hippocampal-Cortical Communication during Learning. Nat. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 1229–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araque, A.; Carmignoto, G.; Haydon, P.G.; Oliet, S.H.R.; Robitaille, R.; Volterra, A. Gliotransmitters Travel in Time and Space. Neuron 2014, 81, 728–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goenaga, J.; Araque, A.; Kofuji, P.; Herrera Moro Chao, D. Calcium Signaling in Astrocytes and Gliotransmitter Release. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1138577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Fellin, T.; Zhu, Y.; Lee, S.-Y.; Auberson, Y.P.; Meaney, D.F.; Coulter, D.A.; Carmignoto, G.; Haydon, P.G. Enhanced Astrocytic Ca2+ Signals Contribute to Neuronal Excitotoxicity after Status Epilepticus. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 10674–10684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Jiang, L.; Goldman, S.A.; Nedergaard, M. Astrocyte-Mediated Potentiation of Inhibitory Synaptic Transmission. Nat. Neurosci. 1998, 1, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigetomi, E.; Suzuki, H.; Hirayama, Y.J.; Sano, F.; Nagai, Y.; Yoshihara, K.; Koga, K.; Tateoka, T.; Yoshioka, H.; Shinozaki, Y.; et al. Disease-Relevant Upregulation of P2Y1 Receptor in Astrocytes Enhances Neuronal Excitability via IGFBP2. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parpura, V.; Basarsky, T.A.; Liu, F.; Jeftinija, K.; Jeftinija, S.; Haydon, P.G. Glutamate-Mediated Astrocyte-Neuron Signalling. Nature 1994, 369, 744–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalo, U.; Palygin, O.; Rasooli-Nejad, S.; Andrew, J.; Haydon, P.G.; Pankratov, Y. Exocytosis of ATP from Astrocytes Modulates Phasic and Tonic Inhibition in the Neocortex. PLoS Biol. 2014, 12, e1001747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henneberger, C.; Papouin, T.; Oliet, S.H.R.; Rusakov, D.A. Long-Term Potentiation Depends on Release of d-Serine from Astrocytes. Nature 2010, 463, 232–236. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, B.-E.; Lee, C.J. GABA as a Rising Gliotransmitter. Front. Neural. Circuits 2014, 8, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, J.T.; Balu, D.; Wolosker, H. D-Serine, the Shape-Shifting NMDA Receptor Co-Agonist. Neurochem. Res. 2020, 45, 1344–1353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lovatt, D.; Xu, Q.; Liu, W.; Takano, T.; Smith, N.A.; Schnermann, J.; Tieu, K.; Nedergaard, M. Neuronal Adenosine Release, and Not Astrocytic ATP Release, Mediates Feedback Inhibition of Excitatory Activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 6265–6270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florian, C.; Vecsey, C.G.; Halassa, M.M.; Haydon, P.G.; Abel, T. Astrocyte-Derived Adenosine and A1 Receptor Activity Contribute to Sleep Loss-Induced Deficits in Hippocampal Synaptic Plasticity and Memory in Mice. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 6956–6962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, J.; Min, J.O.; Kang, D.-S.; Kim, Y.S.; Jung, G.H.; Park, H.J.; Kim, S.; An, H.; Kwon, J.; Kim, J.; et al. Control of Motor Coordination by Astrocytic Tonic GABA Release through Modulation of Excitation/Inhibition Balance in Cerebellum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 5004–5009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltsev, A.; Roshchin, M.; Bezprozvanny, I.; Smirnov, I.; Vlasova, O.; Balaban, P.; Borodinova, A. Bidirectional Regulation by “Star Forces”: Ionotropic Astrocyte’s Optical Stimulation Suppresses Synaptic Plasticity, Metabotropic One Strikes Back. Hippocampus 2023, 33, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Zhou, J.; Sun, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, C. A Computational Model to Investigate GABA-Activated Astrocyte Modulation of Neuronal Excitation. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2020, 2020, 8750167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiacco, T.A.; McCarthy, K.D. Multiple Lines of Evidence Indicate That Gliotransmission Does Not Occur under Physiological Conditions. J. Neurosci. 2018, 38, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, S.A.; Barres, B.A. Looks Can Be Deceiving: Reconsidering the Evidence for Gliotransmission. Neuron 2014, 84, 1112–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves-Ribeiro, J.; Vaz, S.H. The IP3R2 Knockout Mice in Behavior: A Blessing or a Curse? J. Neurochem. 2025, 169, e70062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agulhon, C.; Fiacco, T.A.; McCarthy, K.D. Hippocampal Short- and Long-Term Plasticity Are Not Modulated by Astrocyte Ca2+ Signaling. Science 2010, 327, 1250–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savtchouk, I.; Volterra, A. Gliotransmission: Beyond Black-and-White. J. Neurosci. 2018, 38, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolosker, H.; Balu, D.T.; Coyle, J.T. Astroglial versus Neuronal D-Serine: Check Your Controls! Trends Neurosci. 2017, 40, 520–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papouin, T.; Henneberger, C.; Rusakov, D.A.; Oliet, S.H.R. Astroglial versus Neuronal D-Serine: Fact Checking. Trends Neurosci. 2017, 40, 517–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahlender, D.A.; Savtchouk, I.; Volterra, A. What Do We Know about Gliotransmitter Release from Astrocytes? Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajarillo, E.; Rizor, A.; Lee, J.; Aschner, M.; Lee, E. The Role of Astrocytic Glutamate Transporters GLT-1 and GLAST in Neurological Disorders: Potential Targets for Neurotherapeutics. Neuropharmacology 2019, 161, 107559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataveljic, D.; Pivonkova, H.; de Concini, V.; Hébert, B.; Ezan, P.; Briault, S.; Bemelmans, A.-P.; Pichon, J.; Menuet, A.; Rouach, N. Astroglial Kir4.1 Potassium Channel Deficit Drives Neuronal Hyperexcitability and Behavioral Defects in Fragile X Syndrome Mouse Model. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, S. Lactate Shuttles in Neuroenergetics-Homeostasis, Allostasis and Beyond. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Dube, S.E.; Park, C.B. Brain Energy Homeostasis: The Evolution of the Astrocyte-Neuron Lactate Shuttle Hypothesis. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2025, 29, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christopherson, K.S.; Ullian, E.M.; Stokes, C.C.A.; Mullowney, C.E.; Hell, J.W.; Agah, A.; Lawler, J.; Mosher, D.F.; Bornstein, P.; Barres, B.A. Thrombospondins Are Astrocyte-Secreted Proteins That Promote CNS Synaptogenesis. Cell 2005, 120, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucukdereli, H.; Allen, N.J.; Lee, A.T.; Feng, A.; Ozlu, M.I.; Conatser, L.M.; Chakraborty, C.; Workman, G.; Weaver, M.; Sage, E.H.; et al. Control of Excitatory CNS Synaptogenesis by Astrocyte-Secreted Proteins Hevin and SPARC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, E440-9. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.K.; Stogsdill, J.A.; Pulimood, N.S.; Dingsdale, H.; Kim, Y.H.; Pilaz, L.-J.; Kim, I.H.; Manhaes, A.C.; Rodrigues, W.S., Jr.; Pamukcu, A.; et al. Astrocytes Assemble Thalamocortical Synapses by Bridging NRX1α and NL1 via Hevin. Cell 2016, 164, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.-J.; Jia, M.; Cai, M.; Feng, X.; Huang, L.-N.; Yang, J.-J. Central Neuropeptides as Key Modulators of Astrocyte Function in Neurodegenerative and Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Psychopharmacology 2025, 242, 2353–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, M.; Cuartero, M.I.; Palenzuela, R.; Draffin, J.E.; Konomi, A.; Serra, I.; Colié, S.; Castaño-Castaño, S.; Hasan, M.T.; Nebreda, Á.R.; et al. Astrocytic P38α MAPK Drives NMDA Receptor-Dependent Long-Term Depression and Modulates Long-Term Memory. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2968. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Durkee, C.; Kofuji, P.; Navarrete, M.; Araque, A. Astrocyte and Neuron Cooperation in Long-Term Depression. Trends Neurosci. 2021, 44, 837–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santello, M.; Toni, N.; Volterra, A. Astrocyte Function from Information Processing to Cognition and Cognitive Impairment. Nat. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volterra, A.; Liaudet, N.; Savtchouk, I. Astrocyte Ca2+ Signalling: An Unexpected Complexity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014, 15, 327–335. [Google Scholar]

- Semyanov, A.; Henneberger, C.; Agarwal, A. Making Sense of Astrocytic Calcium Signals—From Acquisition to Interpretation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2020, 21, 551–564. [Google Scholar]

- Lia, A.; Henriques, V.J.; Zonta, M.; Chiavegato, A.; Carmignoto, G.; Gómez-Gonzalo, M.; Losi, G. Calcium Signals in Astrocyte Microdomains, a Decade of Great Advances. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2021, 15, 673433. [Google Scholar]

- Pestana, F.; Edwards-Faret, G.; Belgard, T.G.; Martirosyan, A.; Holt, M.G. No Longer Underappreciated: The Emerging Concept of Astrocyte Heterogeneity in Neuroscience. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakh, B.S.; Deneen, B. The Emerging Nature of Astrocyte Diversity. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 42, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht, P.; Duss, S.N.; Becker, D.; Lewis, C.M.; Bohacek, J.; Helmchen, F. Centripetal Integration of Past Events in Hippocampal Astrocytes Regulated by Locus Coeruleus. Nat. Neurosci. 2024, 27, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, X.; Chen, M.B.; Dong, H.; Liu, J.; Südhof, T.C.; Quake, S.R. Spatial Transcriptomics Reveal Neuron-Astrocyte Synergy in Long-Term Memory. Nature 2024, 627, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy-Royal, C.; Ching, S.; Papouin, T. A Conceptual Framework for Astrocyte Function. Nat. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 1848–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denizot, A.; Arizono, M.; Nägerl, U.V.; Berry, H.; De Schutter, E. Control of Ca2+ Signals by Astrocyte Nanoscale Morphology at Tripartite Synapses. Glia 2022, 70, 2378–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kastanenka, K.V.; Moreno-Bote, R.; De Pittà, M.; Perea, G.; Eraso-Pichot, A.; Masgrau, R.; Poskanzer, K.E.; Galea, E. A Roadmap to Integrate Astrocytes into Systems Neuroscience. Glia 2020, 68, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.S.; Ghetti, A.; Pinto-Duarte, A.; Wang, X.; Dziewczapolski, G.; Galimi, F.; Huitron-Resendiz, S.; Piña-Crespo, J.C.; Roberts, A.J.; Verma, I.M.; et al. Astrocytes Contribute to Gamma Oscillations and Recognition Memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E3343-52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellin, T.; Pascual, O.; Gobbo, S.; Pozzan, T.; Haydon, P.G.; Carmignoto, G. Neuronal Synchrony Mediated by Astrocytic Glutamate through Activation of Extrasynaptic NMDA Receptors. Neuron 2004, 43, 729–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewa, K.-I.; Kaseda, K.; Kuwahara, A.; Kubotera, H.; Yamasaki, A.; Awata, N.; Komori, A.; Holtz, M.A.; Kasai, A.; Skibbe, H.; et al. The Astrocytic Ensemble Acts as a Multiday Trace to Stabilize Memory. Nature 2025, 648, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lines, J.; Baraibar, A.; Nanclares, C.; Martin, E.D.; Aguilar, J.; Kofuji, P.; Navarrete, M.; Araque, A. A Spatial Threshold for Astrocyte Calcium Surge. Elife 2024, 12, RP90046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozachkov, L.; Slotine, J.-J.; Krotov, D. Neuron-Astrocyte Associative Memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2417788122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verkhratsky, A.; Nedergaard, M. Physiology of Astroglia. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 239–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arizono, M.; Bannai, H.; Nakamura, K.; Niwa, F.; Enomoto, M.; Matsu-Ura, T.; Miyamoto, A.; Sherwood, M.W.; Nakamura, T.; Mikoshiba, K. Receptor-Selective Diffusion Barrier Enhances Sensitivity of Astrocytic Processes to Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor Stimulation. Sci. Signal. 2012, 5, ra27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Castro, M.A.; Chuquet, J.; Liaudet, N.; Bhaukaurally, K.; Santello, M.; Bouvier, D.; Tiret, P.; Volterra, A. Local Ca2+ Detection and Modulation of Synaptic Release by Astrocytes. Nat. Neurosci. 2011, 14, 1276–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, M.W.; Arizono, M.; Panatier, A.; Mikoshiba, K.; Oliet, S.H.R. Astrocytic IP3Rs: Beyond IP3R2. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2021, 15, 695817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakers, K.; Lake, A.M.; Khazanchi, R.; Ouwenga, R.; Vasek, M.J.; Dani, A.; Dougherty, J.D. Astrocytes Locally Translate Transcripts in Their Peripheral Processes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E3830–E3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazaré, N.; Oudart, M.; Moulard, J.; Cheung, G.; Tortuyaux, R.; Mailly, P.; Mazaud, D.; Bemelmans, A.-P.; Boulay, A.-C.; Blugeon, C.; et al. Local Translation in Perisynaptic Astrocytic Processes Is Specific and Changes after Fear Conditioning. Cell Rep. 2020, 32, 108076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Cruz-Gambra, A.; Baleriola, J. Astrocyte-Secreted Factors Modulate Synaptic Protein Synthesis as Revealed by Puromycin Labeling of Isolated Synaptosomes. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2025, 18, 1427036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Mattioli, M.; Gobert, D.; Stern, E.; Gamache, K.; Colina, R.; Cuello, C.; Sossin, W.; Kaufman, R.; Pelletier, J.; Rosenblum, K.; et al. EIF2alpha Phosphorylation Bidirectionally Regulates the Switch from Short- to Long-Term Synaptic Plasticity and Memory. Cell 2007, 129, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ceglia, R.; Ledonne, A.; Litvin, D.G.; Lind, B.L.; Carriero, G.; Latagliata, E.C.; Bindocci, E.; Di Castro, M.A.; Savtchouk, I.; Vitali, I.; et al. Specialized Astrocytes Mediate Glutamatergic Gliotransmission in the CNS. Nature 2023, 622, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giaume, C.; Naus, C.C.; Sáez, J.C.; Leybaert, L. Glial Connexins and Pannexins in the Healthy and Diseased Brain. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 93–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blomstrand, F.; Aberg, N.D.; Eriksson, P.S.; Hansson, E.; Rönnbäck, L. Extent of Intercellular Calcium Wave Propagation Is Related to Gap Junction Permeability and Level of Connexin-43 Expression in Astrocytes in Primary Cultures from Four Brain Regions. Neuroscience 1999, 92, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scemes, E.; Giaume, C. Astrocyte Calcium Waves: What They Are and What They Do. Glia 2006, 54, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, S.R.; Jones, O.D.; Raymond, C.R.; Sah, P.; Abraham, W.C. Mechanisms of Heterosynaptic Metaplasticity. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aten, S.; Kiyoshi, C.M.; Arzola, E.P.; Patterson, J.A.; Taylor, A.T.; Du, Y.; Guiher, A.M.; Philip, M.; Camacho, E.G.; Mediratta, D.; et al. Ultrastructural View of Astrocyte Arborization, Astrocyte-Astrocyte and Astrocyte-Synapse Contacts, Intracellular Vesicle-like Structures, and Mitochondrial Network. Prog. Neurobiol. 2022, 213, 102264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushong, E.A.; Martone, M.E.; Jones, Y.Z.; Ellisman, M.H. Protoplasmic Astrocytes in CA1 Stratum Radiatum Occupy Separate Anatomical Domains. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poskanzer, K.E.; Yuste, R. Astrocytes Regulate Cortical State Switching in Vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E2675-84. [Google Scholar]

- Bocchi, R.; Thorwirth, M.; Simon-Ebert, T.; Koupourtidou, C.; Clavreul, S.; Kolf, K.; Della Vecchia, P.; Bottes, S.; Jessberger, S.; Zhou, J.; et al. Astrocyte Heterogeneity Reveals Region-Specific Astrogenesis in the White Matter. Nat. Neurosci. 2025, 28, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkee, C.A.; Araque, A. Diversity and Specificity of Astrocyte-Neuron Communication. Neuroscience 2019, 396, 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Agulhon, C.; Petravicz, J.; McMullen, A.B.; Sweger, E.J.; Minton, S.K.; Taves, S.R.; Casper, K.B.; Fiacco, T.A.; McCarthy, K.D. What Is the Role of Astrocyte Calcium in Neurophysiology? Neuron 2008, 59, 932–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirvalkar, P.R.; Rapp, P.R.; Shapiro, M.L. Bidirectional Changes to Hippocampal Theta-Gamma Comodulation Predict Memory for Recent Spatial Episodes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 7054–7059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenke, F.; Gerstner, W. Hebbian Plasticity Requires Compensatory Processes on Multiple Timescales. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 372, 20160259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, I.; Martín-Monteagudo, C.; Sánchez Romero, J.; Quintanilla, J.P.; Ganchala, D.; Arevalo, M.-A.; García-Marqués, J.; Navarrete, M. Astrocyte Ensembles Manipulated with AstroLight Tune Cue-Motivated Behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 2025, 28, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamsky, A.; Kol, A.; Kreisel, T.; Doron, A.; Ozeri-Engelhard, N.; Melcer, T.; Refaeli, R.; Horn, H.; Regev, L.; Groysman, M.; et al. Astrocytic Activation Generates DE Novo Neuronal Potentiation and Memory Enhancement. Cell 2018, 174, 59–71.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-H.; Jin, S.-Y.; Yang, J.-M.; Gao, T.-M. The Memory Orchestra: Contribution of Astrocytes. Neurosci. Bull. 2023, 39, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trpevski, D.; Khodadadi, Z.; Carannante, I.; Hellgren Kotaleski, J. Glutamate Spillover Drives Robust All-or-None Dendritic Plateau Potentials-an in Silico Investigation Using Models of Striatal Projection Neurons. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1196182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hires, S.A.; Zhu, Y.; Tsien, R.Y. Optical Measurement of Synaptic Glutamate Spillover and Reuptake by Linker Optimized Glutamate-Sensitive Fluorescent Reporters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 4411–4416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordleeva, S.Y.; Stasenko, S.V.; Semyanov, A.V.; Dityatev, A.E.; Kazantsev, V.B. Bi-Directional Astrocytic Regulation of Neuronal Activity within a Network. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papouin, T.; Dunphy, J.; Tolman, M.; Foley, J.C.; Haydon, P.G. Astrocytic Control of Synaptic Function. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 372, 20160154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochmuth, L.; Hirrlinger, J. Physiological and Pathological Role of MTOR Signaling in Astrocytes. Neurochem. Res. 2024, 50, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winfree, R.L.; Nolan, E.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; Gifford, K.A.; Pechman, K.R.; Schneider, J.; Bennett, D.A.; Petyuk, V.A.; Jefferson, A.L.; et al. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor-1 (FLT1) Interactions with Amyloid-Beta in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Putative Biomarker of Amyloid-Induced Vascular Damage. Neurobiol. Aging 2025, 147, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiou, B.; Neely, E.B.; Mcdevitt, D.S.; Simpson, I.A.; Connor, J.R. Transferrin and H-Ferritin Involvement in Brain Iron Acquisition during Postnatal Development: Impact of Sex and Genotype. J. Neurochem. 2020, 152, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, C.M.; Aksamaz, S.; Schulz, S.; Teutsch, J.; Sicinski, P.; Liss, B.; Kätzel, D. Schizophrenia-Related Cognitive Dysfunction in the Cyclin-D2 Knockout Mouse Model of Ventral Hippocampal Hyperactivity. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, A.H.; Nucifora, F.C., Jr.; Blondel, O.; Sheppard, C.A.; Zhang, C.; Snyder, S.H.; Russell, J.T.; Ryugo, D.K.; Ross, C.A. Differential Cellular Expression of Isoforms of Inositol 1,4,5-Triphosphate Receptors in Neurons and Glia in Brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 1999, 406, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Maekawa, S.; Morita, M. Astrocyte Calcium Waves Propagate Proximally by Gap Junction and Distally by Extracellular Diffusion of ATP Released from Volume-Regulated Anion Channels. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mothet, J.-P.; Pollegioni, L.; Ouanounou, G.; Martineau, M.; Fossier, P.; Baux, G. Glutamate Receptor Activation Triggers a Calcium-Dependent and SNARE Protein-Dependent Release of the Gliotransmitter D-Serine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 5606–5611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miguel-Quesada, C.; Zaforas, M.; Herrera-Pérez, S.; Lines, J.; Fernández-López, E.; Alonso-Calviño, E.; Ardaya, M.; Soria, F.N.; Araque, A.; Aguilar, J.; et al. Astrocytes Adjust the Dynamic Range of Cortical Network Activity to Control Modality-Specific Sensory Information Processing. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordleeva, S.Y.; Ermolaeva, A.V.; Kastalskiy, I.A.; Kazantsev, V.B. Astrocyte as Spatiotemporal Integrating Detector of Neuronal Activity. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henneberger, C.; Bard, L.; Panatier, A.; Reynolds, J.P.; Kopach, O.; Medvedev, N.I.; Minge, D.; Herde, M.K.; Anders, S.; Kraev, I.; et al. LTP Induction Boosts Glutamate Spillover by Driving Withdrawal of Perisynaptic Astroglia. Neuron 2020, 108, 919–936.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halassa, M.M.; Fellin, T.; Takano, H.; Dong, J.-H.; Haydon, P.G. Synaptic Islands Defined by the Territory of a Single Astrocyte. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 6473–6477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, M.K.; Collard, M.; Tse, V.; Reitman, M.E.; Etchenique, R.; Kirst, C.; Poskanzer, K.E. Network-Level Encoding of Local Neurotransmitters in Cortical Astrocytes. Nature 2024, 629, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.J.; Lyons, D.A. Glia as Architects of Central Nervous System Formation and Function. Science 2018, 362, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, F.; Kasai, A.; Soto, J.S.; Yu, X.; Qu, Z.; Hashimoto, H.; Gradinaru, V.; Kawaguchi, R.; Khakh, B.S. Molecular Basis of Astrocyte Diversity and Morphology across the CNS in Health and Disease. Science 2022, 378, eadc9020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stogsdill, J.A.; Ramirez, J.; Liu, D.; Kim, Y.H.; Baldwin, K.T.; Enustun, E.; Ejikeme, T.; Ji, R.-R.; Eroglu, C. Astrocytic Neuroligins Control Astrocyte Morphogenesis and Synaptogenesis. Nature 2017, 551, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, W.T.; Abrahamsson, T.; Chierzi, S.; Lui, C.; Zaelzer, C.; Jones, E.V.; Bally, B.P.; Chen, G.G.; Théroux, J.-F.; Peng, J.; et al. Neurons Diversify Astrocytes in the Adult Brain through Sonic Hedgehog Signaling. Science 2016, 351, 849–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabó, Z.; Héja, L.; Szalay, G.; Kékesi, O.; Füredi, A.; Szebényi, K.; Dobolyi, Á.; Orbán, T.I.; Kolacsek, O.; Tompa, T.; et al. Extensive Astrocyte Synchronization Advances Neuronal Coupling in Slow Wave Activity in Vivo. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.-J.; Aćimović, J.; Manninen, T.; Ahokainen, I.; Stapmanns, J.; Lehtimäki, M.; Diesmann, M.; van Albada, S.J.; Plesser, H.E.; Linne, M.-L. Modeling Neuron-Astrocyte Interactions in Neural Networks Using Distributed Simulation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2025, 21, e1013503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kofuji, P.; Araque, A. Astrocytes and Behavior. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2021, 44, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Gomes, S.; Sousa, N.; Pinto, L.; Oliveira, J.F. Functional Roles of Astrocyte Calcium Elevations: From Synapses to Behavior. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2017, 11, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haydon, P.G.; Nedergaard, M. How Do Astrocytes Participate in Neural Plasticity? Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014, 7, a020438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koizumi, S.; Fujishita, K.; Tsuda, M.; Shigemoto-Mogami, Y.; Inoue, K. Dynamic Inhibition of Excitatory Synaptic Transmission by Astrocyte-Derived ATP in Hippocampal Cultures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 11023–11028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Untiet, V.; Beinlich, F.R.M.; Kusk, P.; Kang, N.; Ladrón-de-Guevara, A.; Song, W.; Kjaerby, C.; Andersen, M.; Hauglund, N.; Bojarowska, Z.; et al. Astrocytic Chloride Is Brain State Dependent and Modulates Inhibitory Neurotransmission in Mice. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theparambil, S.M.; Kopach, O.; Braga, A.; Nizari, S.; Hosford, P.S.; Sagi-Kiss, V.; Hadjihambi, A.; Konstantinou, C.; Esteras, N.; Gutierrez Del Arroyo, A.; et al. Adenosine Signalling to Astrocytes Coordinates Brain Metabolism and Function. Nature 2024, 632, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batiuk, M.Y.; Martirosyan, A.; Wahis, J.; de Vin, F.; Marneffe, C.; Kusserow, C.; Koeppen, J.; Viana, J.F.; Oliveira, J.F.; Voet, T.; et al. Identification of Region-Specific Astrocyte Subtypes at Single Cell Resolution. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, A.L.; Wicki-Stordeur, L.E.; Murai, K.K.; Swayne, L.A. Foundations and Implications of Astrocyte Heterogeneity during Brain Development and Disease. Trends Neurosci. 2022, 45, 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrero-Navarro, Á.; Puche-Aroca, L.; Moreno-Juan, V.; Sempere-Ferràndez, A.; Espinosa, A.; Susín, R.; Torres-Masjoan, L.; Leyva-Díaz, E.; Karow, M.; Figueres-Oñate, M.; et al. Astrocytes and Neurons Share Region-Specific Transcriptional Signatures That Confer Regional Identity to Neuronal Reprogramming. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabe8978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos, M.; Bosson, A.; Riebe, I.; Reynell, C.; Vallée, J.; Laplante, I.; Panatier, A.; Robitaille, R.; Lacaille, J.-C. Astrocytes Detect and Upregulate Transmission at Inhibitory Synapses of Somatostatin Interneurons onto Pyramidal Cells. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittolo, S.; Yokoyama, S.; Willoughby, D.D.; Taylor, C.R.; Reitman, M.E.; Tse, V.; Wu, Z.; Etchenique, R.; Li, Y.; Poskanzer, K.E. Dopamine Activates Astrocytes in Prefrontal Cortex via A1-Adrenergic Receptors. Cell Rep. 2022, 40, 111426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mederos, S.; Sánchez-Puelles, C.; Esparza, J.; Valero, M.; Ponomarenko, A.; Perea, G. GABAergic Signaling to Astrocytes in the Prefrontal Cortex Sustains Goal-Directed Behaviors. Nat. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Pozo, A.; Li, H.; Li, Z.; Muñoz-Castro, C.; Jaisa-Aad, M.; Healey, M.A.; Welikovitch, L.A.; Jayakumar, R.; Bryant, A.G.; Noori, A.; et al. Astrocyte Transcriptomic Changes along the Spatiotemporal Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2024, 27, 2384–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, B.L.L.; Liddelow, S.A. Heterogeneity of Astrocyte Reactivity. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2025, 48, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.J.; Eroglu, C. Cell Biology of Astrocyte-Synapse Interactions. Neuron 2017, 96, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, W.-S.; Allen, N.J.; Eroglu, C. Astrocytes Control Synapse Formation, Function, and Elimination. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015, 7, a020370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, T.; Wallace, J.T.; Baldwin, K.T.; Purkey, A.M.; Uezu, A.; Courtland, J.L.; Soderblom, E.J.; Shimogori, T.; Maness, P.F.; Eroglu, C.; et al. Chemico-Genetic Discovery of Astrocytic Control of Inhibition in Vivo. Nature 2020, 588, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, T.; Soderling, S.H. Tripartite Synaptomics: Cell-Surface Proximity Labeling in Vivo. Neurosci. Res. 2021, 173, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Muthukumar, A.K.; Stork, T.; Coutinho-Budd, J.C.; Freeman, M.R. Focal Adhesion Molecules Regulate Astrocyte Morphology and Glutamate Transporters to Suppress Seizure-like Behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 11316–11321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.X.; Bindu, D.S.; Hardin, E.J.; Sakers, K.; Baumert, R.; Ramirez, J.J.; Savage, J.T.; Eroglu, C. δ-Catenin Controls Astrocyte Morphogenesis via Layer-Specific Astrocyte-Neuron Cadherin Interactions. J. Cell Biol. 2023, 222, e202303138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolakopoulou, A.M.; Koeppen, J.; Garcia, M.; Leish, J.; Obenaus, A.; Ethell, I.M. Astrocytic Ephrin-B1 Regulates Synapse Remodeling Following Traumatic Brain Injury. ASN Neuro. 2016, 8, 1759091416630220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Lin, J.; Lau, J.K.Y.; Fu, W.-Y.; Fu, A.K.Y.; Ip, N.Y. Astrocytic EphA4 Signaling Is Important for the Elimination of Excitatory Synapses in Alzheimer’s Disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2420324122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyzack, G.E.; Hall, C.E.; Sibley, C.R.; Cymes, T.; Forostyak, S.; Carlino, G.; Meyer, I.F.; Schiavo, G.; Zhang, S.-C.; Gibbons, G.M.; et al. A Neuroprotective Astrocyte State Is Induced by Neuronal Signal EphB1 but Fails in ALS Models. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, W.-S.; Clarke, L.E.; Wang, G.X.; Stafford, B.K.; Sher, A.; Chakraborty, C.; Joung, J.; Foo, L.C.; Thompson, A.; Chen, C.; et al. Astrocytes Mediate Synapse Elimination through MEGF10 and MERTK Pathways. Nature 2013, 504, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-Y.; Kim, H.; Chung, W.-S.; Park, H. Selective Regulation of Corticostriatal Synapses by Astrocytic Phagocytosis. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietiläinen, O.; Trehan, A.; Meyer, D.; Mitchell, J.; Tegtmeyer, M.; Valakh, V.; Gebre, H.; Chen, T.; Vartiainen, E.; Farhi, S.L.; et al. Astrocytic Cell Adhesion Genes Linked to Schizophrenia Correlate with Synaptic Programs in Neurons. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 111988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, E.; Nemesh, J.; Goldman, M.; Kamitaki, N.; Reed, N.; Handsaker, R.E.; Genovese, G.; Vogelgsang, J.S.; Gerges, S.; Kashin, S.; et al. A Concerted Neuron-Astrocyte Program Declines in Ageing and Schizophrenia. Nature 2024, 627, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, A.; Stern, S.A.; Bozdagi, O.; Huntley, G.W.; Walker, R.H.; Magistretti, P.J.; Alberini, C.M. Astrocyte-Neuron Lactate Transport Is Required for Long-Term Memory Formation. Cell 2011, 144, 810–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Fernandez, M.; Jamison, S.; Robin, L.M.; Zhao, Z.; Martin, E.D.; Aguilar, J.; Benneyworth, M.A.; Marsicano, G.; Araque, A. Synapse-Specific Astrocyte Gating of Amygdala-Related Behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 2017, 20, 1540–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazhe, A.; Verisokin, A.; Verveyko, D.; Postnov, D. Astrocytes: New Evidence, New Models, New Roles. Biophys. Rev. 2023, 15, 1303–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caudle, R.M. Memory in Astrocytes: A Hypothesis. Theor. Biol. Med. Model. 2006, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kol, A.; Goshen, I. The Memory Orchestra: The Role of Astrocytes and Oligodendrocytes in Parallel to Neurons. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2021, 67, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaume, C.; Koulakoff, A.; Roux, L.; Holcman, D.; Rouach, N. Astroglial Networks: A Step Further in Neuroglial and Gliovascular Interactions. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnis, J.; Montana, V.; Delgado-Martinez, I.; Matyash, V.; Parpura, V.; Kettenmann, H.; Sekler, I.; Nolte, C. Mitochondrial Exchanger NCLX Plays a Major Role in the Intracellular Ca2+ Signaling, Gliotransmission, and Proliferation of Astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 7206–7219. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, J.G.; Robinson, M.B. Reciprocal Regulation of Mitochondrial Dynamics and Calcium Signaling in Astrocyte Processes. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 15199–15213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhratsky, A.; Rodríguez, J.J.; Parpura, V. Calcium Signalling in Astroglia. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2012, 353, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pittà, M.; Brunel, N. Multiple Forms of Working Memory Emerge from Synapse-Astrocyte Interactions in a Neuron-Glia Network Model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2207912119. [Google Scholar]

- Krotov, D.; Hopfield, J. Large Associative Memory Problem in Neurobiology and Machine Learning. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krotov, D.; Hopfield, J.J. Dense Associative Memory for Pattern Recognition. arXiv 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozachkov, L.; Kastanenka, K.V.; Krotov, D. Building Transformers from Neurons and Astrocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2219150120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsauer, H.; Schäfl, B.; Lehner, J.; Seidl, P.; Widrich, M.; Adler, T.; Gruber, L.; Holzleitner, M.; Pavlović, M.; Sandve, G.K.; et al. Hopfield Networks Is All You Need. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, J.A.; Sáez, P.J.; Shoji, K.F.; Schalper, K.A.; Palacios-Prado, N.; Velarde, V.; Giaume, C.; Bennett, M.V.L.; Sáez, J.C. Modulation of Brain Hemichannels and Gap Junction Channels by Pro-Inflammatory Agents and Their Possible Role in Neurodegeneration. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 369–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Yu, H.-X.; Sun, M.-L.; Wang, Y.; Xi, W.; Yu, Y.-Q. Astrocyte-Restricted Disruption of Connexin-43 Impairs Neuronal Plasticity in Mouse Barrel Cortex. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2014, 39, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto-Duarte, A.; Roberts, A.J.; Ouyang, K.; Sejnowski, T.J. Impairments in Remote Memory Caused by the Lack of Type 2 IP3 Receptors. Glia 2019, 67, 1976–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paukert, M.; Agarwal, A.; Cha, J.; Doze, V.A.; Kang, J.U.; Bergles, D.E. Norepinephrine Controls Astroglial Responsiveness to Local Circuit Activity. Neuron 2014, 82, 1263–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araque, A.; Martín, E.D.; Perea, G.; Arellano, J.I.; Buño, W. Synaptically Released Acetylcholine Evokes Ca2+ Elevations in Astrocytes in Hippocampal Slices. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 2443–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, C.; Sauer, M.; Geis, C. Super-Resolving Microscopy in Neuroscience. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 11971–12015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Y.; Nagamoto, S.; Takano, T. Synaptic Proteomics Decode Novel Molecular Landscape in the Brain. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2024, 17, 1361956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsubayashi, J.; Takano, T. Proximity Labeling Uncovers the Synaptic Proteome under Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1638627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

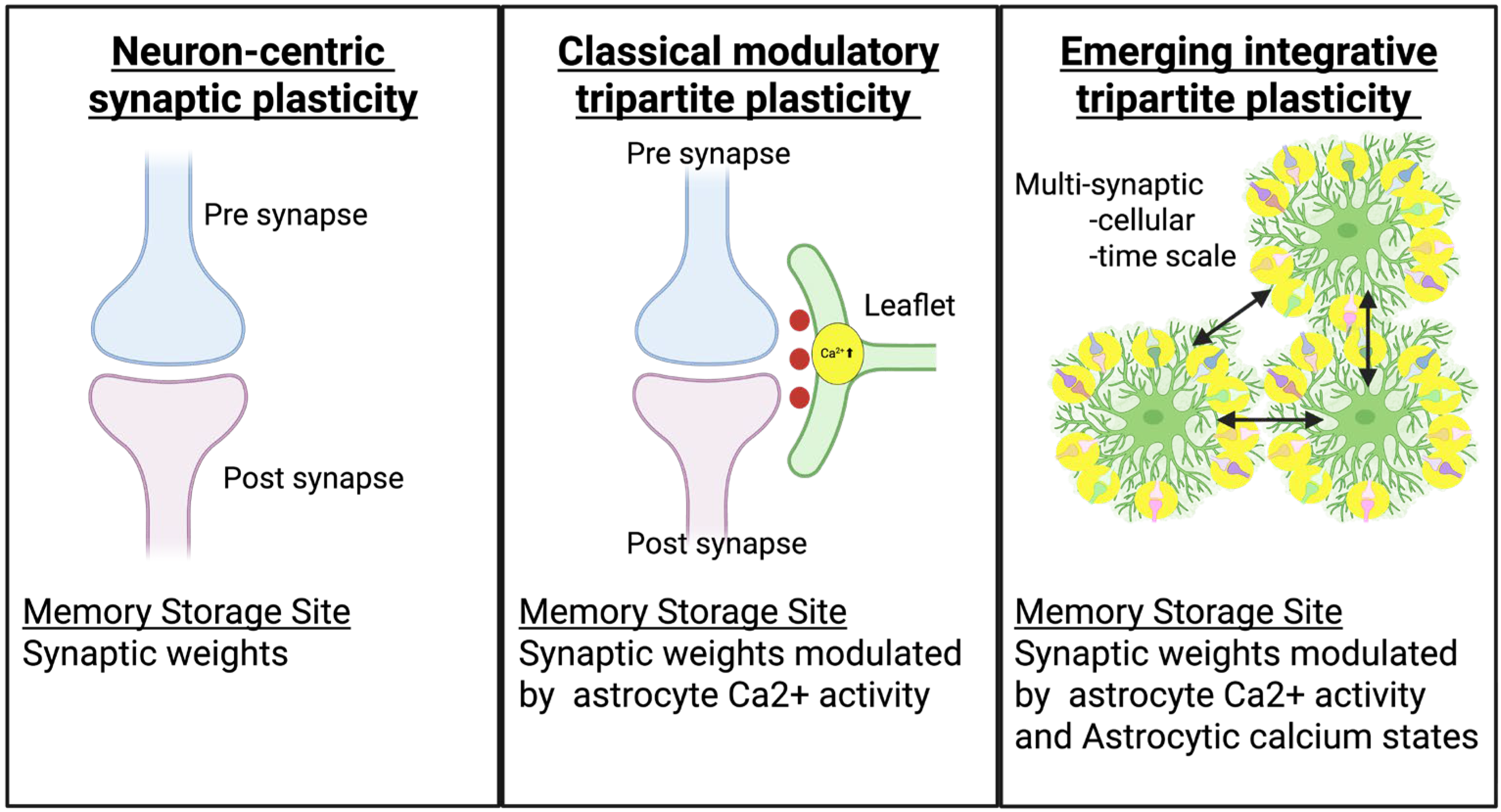

| Dimension | Neuron-Centric Synapse Plasticity | Classical Tripartite Synapse Plasticity | Emerging Integrative Tripartite Synapse Plasticity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Concept | Memory resides exclusively in synaptic weights between neurons; brain computation is purely neuronal | Astrocytes bidirectionally communicate with synapses; modulate synaptic transmission but do not store information | Astrocytes are computational units storing memories; neuron-astrocyte computational partnership |

| Memory Storage Site | Synaptic weights (connection strengths between neurons) | Synaptic weights dynamically modulated by astrocyte Ca2+ activity | Dual storage: synaptic weights + astrocytic Ca2+ state |

| Key Components | Presynaptic neuron + postsynaptic neuron | Presynaptic neuron + postsynaptic neuron + astrocytic leaflet (perisynaptic astrocyte process) single tripartite synapse | Hierarchical multi-scale tripartite coordination: from individual synapses to astrocyte leaflet domain networks implementing higher-order metaplasticity and circuit stabilization |

| Information Processing | Feed-forward and recurrent neural connections; pattern completion via attractor dynamics | Neurons activate astrocytes via neurotransmitters; astrocytes modulate synapses via gliotransmitter release | Parallel processing in neuron and astrocyte networks; astrocytes integrate information across 106 synapses |

| Temporal Dynamics | Milliseconds (action potentials) to seconds (synaptic plasticity) | Milliseconds (neurons) to seconds/minutes (astrocyte Ca2+ waves) | Milliseconds to days: fast neuronal spikes/slow astrocyte Ca2+/multi-day molecular memory traces |

| Spatial Scale | Local synapses and neural circuit ensembles | Local tripartite synapse with limited spatial coordination between synapses | Multi-scale: microdomains (processes), meso-scale (single astrocyte tiles ~106 synapses), macro-scale (astrocyte networks) |

| Astrocyte Role | Not included in computational models | Modulatory support role: sense neurotransmitters (glutamate, GABA), release gliotransmitters (ATP, D-serine) | Active computational partner: memory storage units, pattern recognition, attention-like gating, multi-day trace formation |

| Computational Capacity | Limited to synaptic weight matrix capacity | Slightly enhanced by astrocyte modulation of synaptic weight dynamics | Massively expanded: supralinear memory scaling enables exponential capacity growth with network size |

| Memory Scaling Law | Constant: M/N = constant (memories per neuron remains fixed as network grows) | Similar to neuron-centric: M/N ≈ constant (modulation does not fundamentally change scaling) | Supralinear: M/N grows with N (e.g., M ∝ N3 when astrocytes couple process pairs) |

| Synaptic Weight Control | Static or slowly changing via Hebbian/STDP rules | Dynamically modulated by astrocyte Ca2+ levels and gliotransmitter release timing | Online adaptive control: astrocytes continuously adjust effective synaptic weights based on network state |

| Network Architecture | Hopfield networks, attractor networks, recurrent neural networks | Extended Hopfield networks with astrocyte-mediated gliotransmission feedback loops | Dense Associative Memory, Modern Hopfield Networks; intermediate between DAMs and Transformers |

| Major Biological Basis (Neurons) | Spike generation, LTP/LTD, action potential propagation, synaptic transmission | Synaptic transmission + neurotransmitter receptor activation on astrocytes + bidirectional signaling | Neural activation essential for memory (engram hypothesis); astrocytes collaborate with neuronal ensembles |

| Major Biological Basis (Astrocytes) | Not applicable (astrocytes completely ignored in framework) | Ca2+ waves via IP3R2, gliotransmitter release (glutamate, ATP, D-serine), GPCR activation | Ca2+ microdomains in processes, process-process Ca2+ transport, multi-day molecular traces (IGFBP2, ADRB1 upregulation), ensemble formation |

| Time Period of Dominance | 1980s–2010 (dominant paradigm) | 1999–2020 (peak influence 2005–2015) | 2016–present (accelerating 2020–2025) |

| Primary Advantages | Mathematical elegance, well-understood convergence properties, strong AI/ML connections, computational simplicity | Incorporates astrocyte biology, bidirectional neuron-glia signaling, explains gliotransmitter modulation effects | Explains brain’s massive memory capacity, multi-day stabilization, biologically detailed, supralinear scaling |

| Major Limitations | Ignores astrocytes entirely, lacks temporal dynamics beyond plasticity, limited memory capacity, static weights | Slow Ca2+ waves vs. fast synaptic events, passive modulation role, limited memory capacity enhancement | Complex parameter space, requires experimental validation of process-stored memories, molecular mechanisms incomplete |

| (A) | ||||

| Hierarchical Level | Structural Unit | Key Functional Properties | Memory Mechanism | Key References |

| MICRO-SCALE (nanometer to micrometer) | IP3R-enriched ER fragments and Metabotropic receptors | Ca2+ signals are analog and graded with threshold gating. | IP3R-Ca2+ enables synapse-specific memory encoding; signal substrate | [13,92,95,96,97] |

| Spatially confined Ca2+ zones | Microdomain dynamics; independent per-synapse processing; STDP gating | Synaptic weight encoding via pattern-specific Ca2+ dynamics. Parallel processing of ~100,000 synapses. | [6,7,8,14,32,79,81,84] | |

| Individual astrocyte leaflet | Ca2+-dependent mRNA localization; produces memory-linked proteins. | Long-term memory consolidation via local astrocyte protein synthesis | [12,14,98,99,100,101] | |

| MESO-SCALE (single to few synapses) | Ultra-thin lamellar extension (leaflet) | Rapid Ca2+ transients (80–140 nM); single-synapse detection | Single-synapse memory encoding via Ca2+-gliotransmitter coupling | [7,14,45,46,96,102] |

| Connexin43 gap junctions and luster of interconnected leaflets | Gap junction coupling; cytosolic continuity. ~10 synapses per leaflet; co-activated → merged Ca2+ waves | Coordinated plasticity across synapse clusters. Cooperative processing; collective memory traces | [14,40,41,42,103,104,105,106] | |

| MACRO-SCALE (single astrocyte) | Hierarchical branching system | Hierarchical routing; integrates leaflet signals → soma coordination | Hierarchical memory organization across domains | [40,86,88,92,107] |

| Complete astrocyte territorial domain | 10,000–100,000 synapses per astrocyte, | Single astrocyte memory capacity for ~100,000 synapses | [10,40,94,108,109,110] | |

| (B) | ||||

| Hierarchical Level | Structural Unit | Key Functional Properties | Memory Mechanism | Key References |

| NETWORK-SCALE (multi-astrocyte) | Locally coordinated tripartite clusters | Tripartite synapse coordination; ensemble plasticity | Ensemble-level memory trace formation | [3,4,14,44] |

| Multi-astrocyte network (circuit-level) | Distributed computation; circuit pattern recognition | Circuit-level memory storage; E-I balance maintenance | [10,11,25,52,57,103,111] | |

| Oscillatory control hub | Theta-gamma synchronization; oscillatory power modulation | Theta-gamma coupling for episodic memories; oscillatory encoding | [89,112,113] | |

| Temporal integrator | Seconds-to-minutes integration; metaplasticity gating | Metaplasticity gating; experience-dependent plasticity windows | [6,8,25,88,109,114] | |

| ENSEMBLE-SCALE (learning-activated) | Spatially clustered c-Fos+ astrocytes | NFIA-regulated; c-Fos co-expression with neurons | Direct memory encoding alongside engram neurons | [17,44,115,116,117] |

| LAAs positioned near engram neurons | Physical proximity to engram neurons; bidirectional signaling | Engram stabilization; coordination with neuronal ensembles | [17,91] | |

| Multi-day molecular signatures | Multi-day molecular marks; adrenergic receptor upregulation; IGFBP2 storage | Long-term eligibility traces; resistance to decay | [91] | |

| Distributed ensembles (HC → Amy → PFC) | Multi-region coordination; HC → Amy → PFC progression during consolidation | Consolidation: rapid HC encoding → Amy emotional tagging → PFC storage | [17,44,85,91] | |

| Scale | Structural Dimension | Ca2+ Signal Time Course | Synaptic Coverage/Functional Role | Representative Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microdomain (node–shaft) | 200–400 nm nodes; 50–200 nm shafts | Rise: 20–200 ms; Duration: 0.2–1.5 s | Single-synapse read–write signaling | [13,15] |

| Leaflet domain | ~2–5 µm territory | Ca2+ events 200–800 ms | 5–20 synapses per leaflet | [131] |

| Multi-leaflet region | 10–20 µm | Ca2+ clustering 0.5–2 s | Integrates multisynaptic inputs | [1] |

| Single astrocyte territory | 30–80 µm radius | Ca2+ waves 1–10 s | 105–106 synapses per cell | [108,132] |

| Network level | mm-scale | Slow Ca2+ waves: 5–20 µm/s | Coordinates ensemble-level states | [105] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yamamoto, M.; Takano, T. Astrocyte-Mediated Plasticity: Multi-Scale Mechanisms Linking Synaptic Dynamics to Learning and Memory. Cells 2025, 14, 1936. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241936

Yamamoto M, Takano T. Astrocyte-Mediated Plasticity: Multi-Scale Mechanisms Linking Synaptic Dynamics to Learning and Memory. Cells. 2025; 14(24):1936. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241936

Chicago/Turabian StyleYamamoto, Masaya, and Tetsuya Takano. 2025. "Astrocyte-Mediated Plasticity: Multi-Scale Mechanisms Linking Synaptic Dynamics to Learning and Memory" Cells 14, no. 24: 1936. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241936

APA StyleYamamoto, M., & Takano, T. (2025). Astrocyte-Mediated Plasticity: Multi-Scale Mechanisms Linking Synaptic Dynamics to Learning and Memory. Cells, 14(24), 1936. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241936