Wet Lab Techniques for the Functional Analysis of Circular RNA

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Circular RNA Library Preparation and Sequencing Analysis

| Tool | Mapper or Program | Functions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Find-circ | Bowtie2 | Detect BSJ sites to identify circRNA | [40] |

| CIRI | BWA | [41] | |

| CIRCexplorer | TopHat/STAR | [42] | |

| CIRI-AS | TopHat/STAR/MapSplice/BWA/segemehl | Identify multiple circRNAs from one gene locus. Inspect alternate circularization | [43] |

| CIRCexplorer2 | [44] | ||

| circSPlice | STAR | [45] | |

| CIRCexplorer3-CLER | TopHat/STAR/MapSplice/BWA/segemehl | Identify and compare circRNA with linear RNA expression | [46] |

| CIRIquant | BWA | [47] | |

| DCC | STAR | [48] | |

| miRspongeR | Bioconductor package | Identifies and analyzes miRNA sponge interactions | [36] |

| CircInteractome | Web-based tool | Explores circular RNAs (circRNAs) and their potential interactions with RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and microRNAs (miRNAs) | [37] |

| CircRIP | Available as a command-line tool via its GitHub page | Utilizes RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (RIP-Seq) and enhanced cross-linking immunoprecipitation (eCLIP) data to detect circRNA protein interactions | [38] |

| CircCode | Python 3-based pipeline | Analyzes ribosome profiling data (Ribo-Seq) and predicts whether a given circRNA can be translated | [39] |

3. Detection and Validation of circRNA

3.1. RNA Isolation and Sample Preparation

3.2. circRNA Enrichment Strategies

3.3. RT-qPCR

3.4. Northern Blot

3.5. In Situ Hybridization

4. Identification of RBPs Involved in circRNA Biogenesis

RNA Immunoprecipitation (RIP)

5. Detecting circRNA-Interacting Partners

| Technique | Input | Principle and Advantages | Disadvantages/ Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CircRNA library preparation and sequencing strategies | |||

| RPAD | Total RNA |

|

|

| Isocirc | Total RNA |

|

|

| SinSuper-Seq | Single cells (oocytes, embryos) |

|

|

| Detection and Validation of CircRNAs | |||

| RT-qPCR | cDNA |

|

|

| Northern Blot | Total RNA |

|

|

| In situ hybridization | Fixed tissues |

|

|

| Comparison of different strategies in in situ hybridization | |||

| CircFISH |

|

| |

| BaseScope |

|

| |

| Padlock probe and rolling circle hybridization |

|

| |

| Identification of RBPs involved in circRNA biogenesis | |||

| RIP | Cells or tissue lysates |

|

|

| CLIP | Cells or tissue lysates |

|

|

| PAR-CLIP | Cells or tissue lysates |

|

|

| Detecting circRNA-interacting partners | |||

| Antisense oligomer-based pulldown assay | Cells or tissue lysates |

|

|

| Biotin-coupled miRNA capture assay | Live cells |

|

|

| Functional analysis of circRNA: Overexpression of circRNA | |||

| Plasmids | Live cells/animals |

|

|

| Viral Vectors | Live cells/animals |

|

|

| Transposon-based system | Live cells/animals |

|

|

| Functional analysis of circRNA: CircRNA knockdown or knockout | |||

| SiRNA | Live cells/animals |

|

|

| ShRNA | Live cells/animals |

|

|

| CRISPR–Cas13 | Live cells/animals |

|

|

| CRISPR–Cas9 | Live cells/animals |

|

|

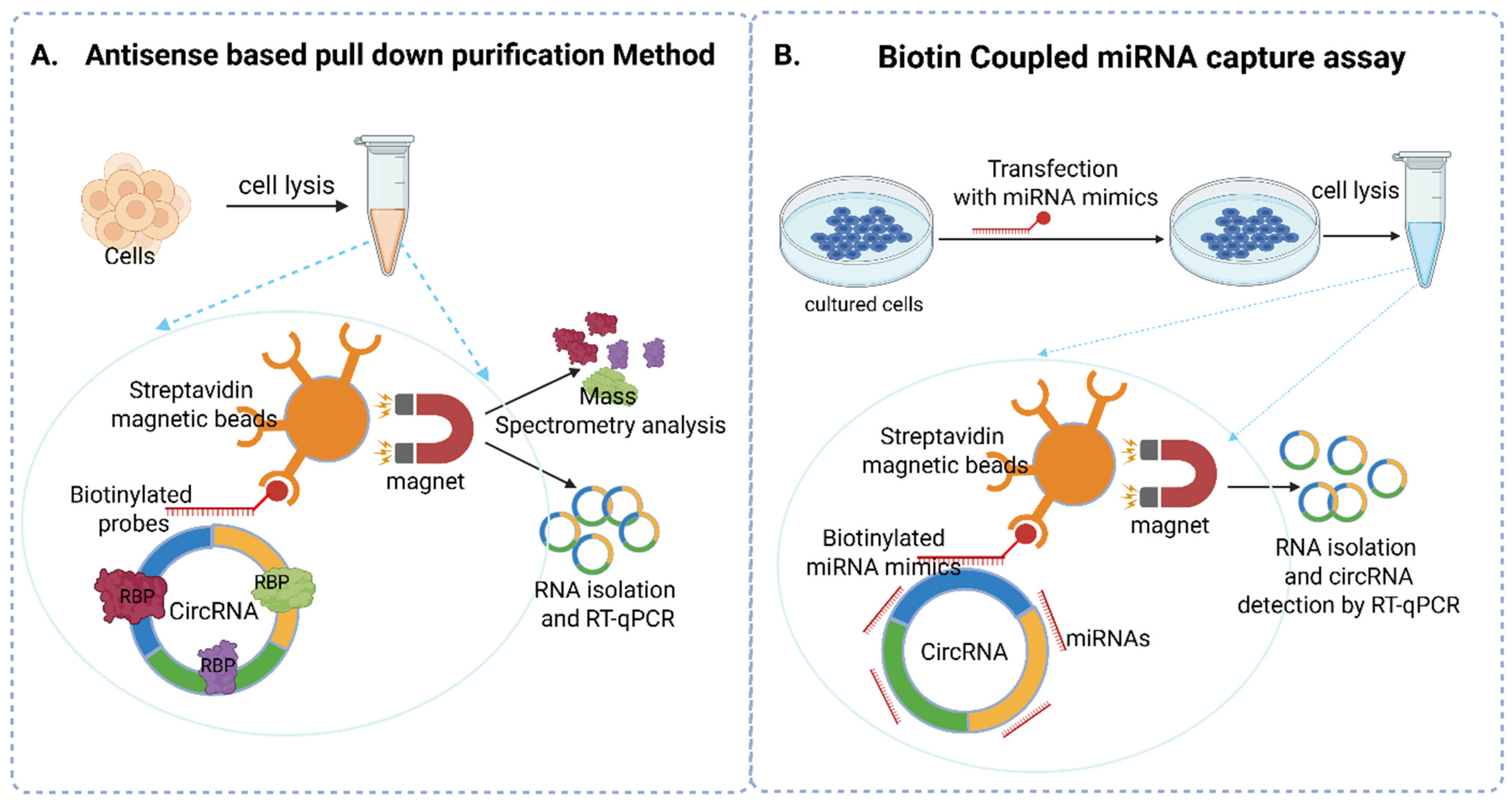

5.1. Antisense Oligomer-Based Pulldown Assay

5.2. Biotin-Coupled miRNA Capture Assay

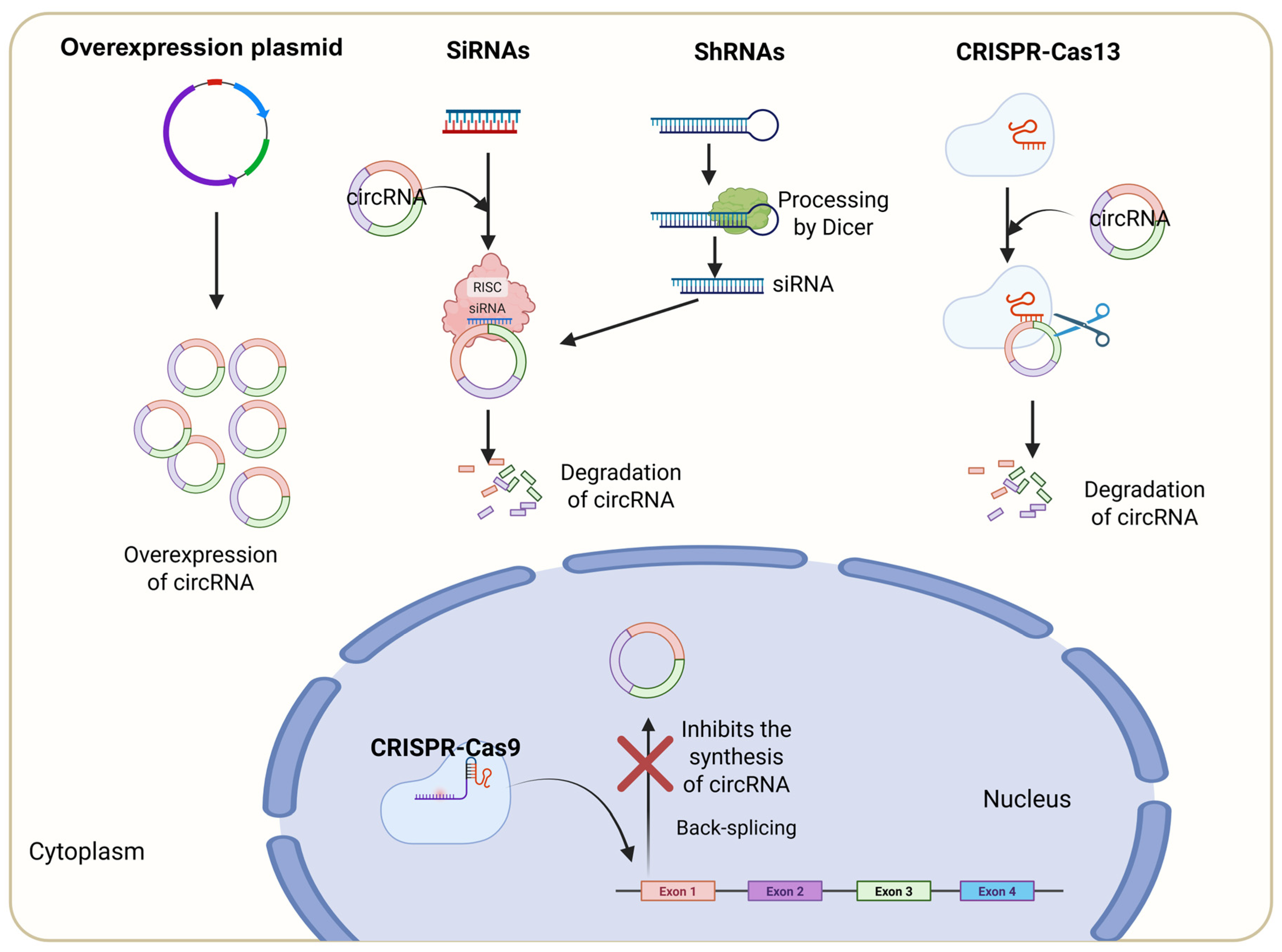

6. Functional Analysis of circRNA

6.1. Overexpression of circRNA

6.2. siRNA-Mediated Depletion of circRNA

6.3. shRNA-Mediated Depletion of circRNA

6.4. CRISPR–Cas9-Induced circRNA Knockout/Knockdown

6.5. CRISPR–Cas13-Induced circRNA Knockdown

6.6. Assays for the Functional Analysis of the circRNA

7. Future Directions

8. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, X.; Cai, Y.; Xu, J. Circular RNAs: Biogenesis, Mechanism, and Function in Human Cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanger, H.L.; Klotz, G.; Riesner, D.; Gross, H.J.; Kleinschmidt, A.K. Viroids are single-stranded covalently closed circular RNA molecules existing as highly base-paired rod-like structures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1976, 73, 3852–3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzman, J.; Gawad, C.; Wang, P.L.; Lacayo, N.; Brown, P.O. Circular RNAs are the predominant transcript isoform from hundreds of human genes in diverse cell types. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westholm, J.O.; Miura, P.; Olson, S.; Shenker, S.; Joseph, B.; Sanfilippo, P.; Celniker, S.E.; Graveley, B.R.; Lai, E.C. Genome-wide analysis of drosophila circular RNAs reveals their structural and sequence properties and age-dependent neural accumulation. Cell Rep. 2014, 9, 1966–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.; Memczak, S.; Wyler, E.; Torti, F.; Porath, H.T.; Orejuela, M.R.; Piechotta, M.; Levanon, E.Y.; Landthaler, M.; Dieterich, C. Analysis of intron sequences reveals hallmarks of circular RNA biogenesis in animals. Cell Rep. 2015, 10, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmohsen, K.; Panda, A.C.; De, S.; Grammatikakis, I.; Kim, J.; Ding, J.; Noh, J.H.; Kim, K.M.; Mattison, J.A.; de Cabo, R. Circular RNAs in monkey muscle: Age-dependent changes. Aging 2015, 7, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.-Y.; Cai, Z.-R.; Liu, J.; Wang, D.-S.; Ju, H.-Q.; Xu, R.-H. Circular RNA: Metabolism, functions and interactions with proteins. Mol. Cancer 2020, 19, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, A.; Jaijyan, D.K.; Yang, S.; Zeng, M.; Pei, S.; Zhu, H. Functions of Circular RNA in Human Diseases and Illnesses. Noncoding RNA 2023, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Zhao, G.; Yan, X.; Lv, Z.; Yin, H.; Zhang, S.; Song, W.; Li, X.; Li, L.; Du, Z.; et al. A novel FLI1 exonic circular RNA promotes metastasis in breast cancer by coordinately regulating TET1 and DNMT1. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwal-Fluss, R.; Meyer, M.; Pamudurti, N.R.; Ivanov, A.; Bartok, O.; Hanan, M.; Evantal, N.; Memczak, S.; Rajewsky, N.; Kadener, S. circRNA biogenesis competes with pre-mRNA splicing. Mol. Cell 2014, 56, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Huang, C.; Bao, C.; Chen, L.; Lin, M.; Wang, X.; Zhong, G.; Yu, B.; Hu, W.; Dai, L.; et al. Exon-intron circular RNAs regulate transcription in the nucleus. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015, 22, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.B.; Jensen, T.I.; Clausen, B.H.; Bramsen, J.B.; Finsen, B.; Damgaard, C.K.; Kjems, J. Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature 2013, 495, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.O.; Chen, T.; Xiang, J.F.; Yin, Q.F.; Xing, Y.H.; Zhu, S.; Yang, L.; Chen, L.L. Circular intronic long noncoding RNAs. Mol. Cell 2013, 51, 792–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Zheng, G.; Ning, Q.; Zheng, J.; Dong, D. Translation and functional roles of circular RNAs in human cancer. Mol. Cancer 2020, 19, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Yu, M.; Yang, G. Roles of circular RNAs in regulating the self-renewal and differentiation of adult stem cells. Differentiation 2020, 113, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wu, J.; Wu, P.; Li, Y. Emerging roles of circular RNAs in stem cells. Genes Dis. 2023, 10, 1920–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, T.; Xiao, J. Circular RNAs: Promising biomarkers for human diseases. EBioMedicine 2018, 34, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisignano, G.; Michael, D.C.; Visal, T.H.; Pirlog, R.; Ladomery, M.; Calin, G.A. Going circular: History, present, and future of circRNAs in cancer. Oncogene 2023, 42, 2783–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussen, B.M.; Abdullah, S.R.; Jaafar, R.M.; Rasul, M.F.; Aroutiounian, R.; Harutyunyan, T.; Samsami, M.; Taheri, M. Circular RNAs as key regulators in cancer hallmarks: New progress and therapeutic opportunities. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2025, 207, 104612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, A.F.; Bindereif, A.; Bozzoni, I.; Hanan, M.; Hansen, T.B.; Irimia, M.; Kadener, S.; Kristensen, L.S.; Legnini, I.; Morlando, M.; et al. Best practice standards for circular RNA research. Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 1208–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Wang, R.C. Research techniques made simple: Studying circular RNA in skin diseases. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 141, 2313–2319.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digby, B.; Finn, S.; Broin, P.Ó. Computational approaches and challenges in the analysis of circRNA data. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobi, T.; Dieterich, C. Computational approaches for circular RNA analysis. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2019, 10, e1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, Z.; Zhongqiang, C.; Caiyun, J.; Yanan, L.; Jianhua, W.; Liang, L. Circular RNA detection methods: A minireview. Talanta 2022, 238, 123066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.R.; Munk, R.; Kundu, G.; De, S.; Abdelmohsen, K.; Gorospe, M. Methods for analysis of circular RNAs. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2020, 11, e1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.R.; Rout, P.K.; Das, A.; Gorospe, M.; Panda, A.C. RPAD (RNase R treatment, polyadenylation, and poly (A)+ RNA depletion) method to isolate highly pure circular RNA. Methods 2019, 155, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, R.; Gao, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, R.; Kadash-Edmondson, K.E.; Liu, B.; Wang, Y.; Lin, L.; Xing, Y. isoCirc catalogs full-length circular RNA isoforms in human transcriptomes. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhang, X.; Wu, X.; Guo, H.; Hu, Y.; Tang, F.; Huang, Y. Single-cell RNA-seq transcriptome analysis of linear and circular RNAs in mouse preimplantation embryos. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Y.; Yan, L.; Hu, B.; Fan, X.; Ren, Y.; Li, R.; Lian, Y.; Yan, J.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Tracing the expression of circular RNAs in human pre-implantation embryos. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.L. The expanding regulatory mechanisms and cellular functions of circular RNAs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, P.; Wu, W.; Chen, S.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, H.; Yan, J.; Zhang, S.; Yang, P.; et al. Expanded Expression Landscape and Prioritization of Circular RNAs in Mammals. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 3444–3460.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Yang, L.; Chen, L.L. The Biogenesis, Functions, and Challenges of Circular RNAs. Mol. Cell 2018, 71, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanan, M.; Soreq, H.; Kadener, S. CircRNAs in the brain. RNA Biol. 2017, 14, 1028–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Bi, Z.Y.; Chen, Z.L.; Liu, C.; Li, L.L.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, Q.; Zhu, W.; Song, Y.Y.; Zhan, B.T.; et al. Emerging landscape of circular RNAs in lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 2018, 427, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.K.; Xue, W.; Chen, L.L.; Yang, L. CIRCexplorer pipelines for circRNA annotation and quantification from non-polyadenylated RNA-seq datasets. Methods 2021, 196, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, L.; Xu, T.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, C.; Li, J.; Le, T.D. miRspongeR: An R/Bioconductor package for the identification and analysis of miRNA sponge interaction networks and modules. BMC Bioinform. 2019, 20, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudekula, D.B.; Panda, A.C.; Grammatikakis, I.; De, S.; Abdelmohsen, K.; Gorospe, M. CircInteractome: A web tool for exploring circular RNAs and their interacting proteins and microRNAs. RNA Biol. 2016, 13, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Chen, K.; Chen, W.; Wang, J.; Chang, L.; Deng, J.; Wei, L.; Han, L.; Huang, C.; He, C. circRIP: An accurate tool for identifying circRNA–RBP interactions. Brief. Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbac186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Li, G. CircCode: A Powerful Tool for Identifying circRNA Coding Ability. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memczak, S.; Jens, M.; Elefsinioti, A.; Torti, F.; Krueger, J.; Rybak, A.; Maier, L.; Mackowiak, S.D.; Gregersen, L.H.; Munschauer, M. Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature 2013, 495, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, F. CIRI: An efficient and unbiased algorithm for de novo circular RNA identification. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.-O.; Wang, H.-B.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, X.; Chen, L.-L.; Yang, L. Complementary sequence-mediated exon circularization. Cell 2014, 159, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Zhao, F. Comprehensive identification of internal structure and alternative splicing events in circular RNAs. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.-O.; Dong, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.-L.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L.-L.; Yang, L. Diverse alternative back-splicing and alternative splicing landscape of circular RNAs. Genome Res. 2016, 26, 1277–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Chen, K.; Dong, X.; Xu, X.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, W.; Han, Y.; Shao, L.; Gao, Y. Genome-wide identification of cancer-specific alternative splicing in circRNA. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.-K.; Wang, M.-R.; Liu, C.-X.; Dong, R.; Carmichael, G.G.; Chen, L.-L.; Yang, L. CIRCexplorer3: A CLEAR pipeline for direct comparison of circular and linear RNA expression. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2019, 17, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Yang, J.; Zhao, F. Accurate quantification of circular RNAs identifies extensive circular isoform switching events. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Metge, F.; Dieterich, C. Specific identification and quantification of circular RNAs from sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 1094–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.; Bodaghi, S.; Osman, F.; Wang, J.; Rucker, T.; Tan, S.-H.; Huang, A.; Pagliaccia, D.; Comstock, S.; Lavagi-Craddock, I. A comparative analysis of RNA isolation methods optimized for high-throughput detection of viral pathogens in California’s regulatory and disease management program for citrus propagative materials. Front. Agron. 2022, 4, 911627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, K.; Sreeja, P.S. RNA Extraction Using Trizol (6-Well Plate Method). In Advanced Cell and Molecular Techniques: Protocols for In Vitro and In Vivo Studies; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 117–120. [Google Scholar]

- Yazdani, H.; Kalantari, S.; Nafar, M.; Naji, M. Phenol Based RNA Isolation is the Optimum Method for Study of Gene Expression in Human Urinary Sediment. J. Sci. Islam. Repub. Iran 2019, 30, 227–231. [Google Scholar]

- Tesena, P.; Korchunjit, W.; Taylor, J.; Wongtawan, T. Comparison of commercial RNA extraction kits and qPCR master mixes for studying gene expression in small biopsy tissue samples from the equine gastric epithelium. J. Equine Sci. 2017, 28, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, D.; Glowatz, H.; Schlumpberger, M. Ribosomal RNA depletion for efficient use of RNA-seq capacity. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2013, 103, 4.19.1–4.19.8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, M.; Amstislavskiy, V.; Risch, T.; Schuette, M.; Dökel, S.; Ralser, M.; Balzereit, D.; Lehrach, H.; Yaspo, M.-L. Influence of RNA extraction methods and library selection schemes on RNA-seq data. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Xue, A.; Tai, J.; Mbadugha, F.; Obi, P.; Mascarenhas, R.; Tyagi, A.; Siena, A.; Chen, Y.G. A scalable and cost-efficient rRNA depletion approach to enrich RNAs for molecular biology investigations. RNA 2024, 30, 728–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeck, W.R.; Sorrentino, J.A.; Wang, K.; Slevin, M.K.; Burd, C.E.; Liu, J.; Marzluff, W.F.; Sharpless, N.E. Circular RNAs are abundant, conserved, and associated with ALU repeats. RNA 2013, 19, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, H.; Zuo, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.Q.; Malhotra, A.; Mayeda, A. Characterization of RNase R-digested cellular RNA source that consists of lariat and circular RNAs from pre-mRNA splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmohsen, K.; Panda, A.C.; Munk, R.; Grammatikakis, I.; Dudekula, D.B.; De, S.; Kim, J.; Noh, J.H.; Kim, K.M.; Martindale, J.L. Identification of HuR target circular RNAs uncovers suppression of PABPN1 translation by CircPABPN1. RNA Biol. 2017, 14, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, A.C.; Grammatikakis, I.; Kim, K.M.; De, S.; Martindale, J.L.; Munk, R.; Yang, X.; Abdelmohsen, K.; Gorospe, M. Identification of senescence-associated circular RNAs (SAC-RNAs) reveals senescence suppressor CircPVT1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 4021–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, A.C.; Gorospe, M. Detection and analysis of circular RNAs by RT-PCR. Bio-Protocol 2018, 8, e2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Lopez, J.P.; Cruceanu, C.; Pierotti, C.; Fiori, L.M.; Squassina, A.; Chillotti, C.; Dieterich, C.; Mellios, N.; Turecki, G. Circular RNA circCCNT2 is upregulated in the anterior cingulate cortex of individuals with bipolar disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, T.; Schreiner, S.; Preußer, C.; Bindereif, A.; Rossbach, O. Northern blot analysis of circular RNAs. Circ. RNAs Methods Protoc. 2018, 1724, 119–133. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Shan, G. Nonradioactive northern blot of circRNAs. Circ. RNAs Methods Protoc. 2018, 1724, 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Long, H.; Zheng, Q.; Bo, X.; Xiao, X.; Li, B. Circular RNA circRHOT1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by initiation of NR2F6 expression. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, J.; Tian, Y.; Gao, Y.; Dong, X.; Chen, W.; Yuan, X.; Yin, W.; Xu, J.; Chen, K.; et al. CircRNA inhibits DNA damage repair by interacting with host gene. Mol. Cancer 2020, 19, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Tong, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, S.; Lei, Z.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Li, C.; Zhao, J.; et al. Circular RNA hsa_circ_0008305 (circPTK2) inhibits TGF-β-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis by controlling TIF1γ in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Yuan, W.; Yang, X.; Li, P.; Wang, J.; Han, J.; Tao, J.; Li, P.; Yang, H.; Lv, Q.; et al. Circular RNA circ-ITCH inhibits bladder cancer progression by sponging miR-17/miR-224 and regulating p21, PTEN expression. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppula, A.; Abdelgawad, A.; Guarnerio, J.; Batish, M.; Parashar, V. CircFISH: A novel method for the simultaneous imaging of linear and circular RNAs. Cancers 2022, 14, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.-M.; Huang, W.; Wang, X.-M.M.; Jansen, M.; Ma, X.-J.; Kim, J.; Anderson, C.M.; Wu, X.; Pan, L.; Su, N. Robust RNA-based in situ mutation detection delineates colorectal cancer subclonal evolution. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejugam, P.R.; Das, A.; Panda, A.C. Seeing is believing: Visualizing circular RNAs. Non-Coding RNA 2020, 6, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.R.; Yang, J.-H.; Tsitsipatis, D.; Panda, A.C.; Noh, J.H.; Kim, K.M.; Munk, R.; Nicholson, T.; Hanniford, D.; Argibay, D. circSamd4 represses myogenic transcriptional activity of PUR proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 3789–3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Yu, T.; Jing, X.; Ma, L.; Fan, Y.; Yang, F.; Ma, P.; Jiang, H.; Wu, X.; Shu, Y. Exosomal circSHKBP1 promotes gastric cancer progression via regulating the miR-582-3p/HUR/VEGF axis and suppressing HSP90 degradation. Mol. Cancer 2020, 19, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Li, Y.; Zheng, W.; Xie, N.; Shi, Y.; Long, Z.; Xie, L.; Fazli, L.; Zhang, D.; Gleave, M. Characterization of a prostate-and prostate cancer-specific circular RNA encoded by the androgen receptor gene. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2019, 18, 916–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhou, Q.; Qiu, Q.; Hou, L.; Wu, M.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Lu, B.; Cheng, X.; Liu, P. CircPLEKHM3 acts as a tumor suppressor through regulation of the miR-9/BRCA1/DNAJB6/KLF4/AKT1 axis in ovarian cancer. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suenkel, C.; Cavalli, D.; Massalini, S.; Calegari, F.; Rajewsky, N. A highly conserved circular RNA is required to keep neural cells in a progenitor state in the mammalian brain. Cell Rep. 2020, 30, 2170–2179.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, K.; Chen, D.; Wang, Z.; Ma, J.; Zhou, J.; Chen, N.; Lv, L.; Zheng, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhang, Y. Annotation and functional clustering of circRNA expression in rhesus macaque brain during aging. Cell Discov. 2018, 4, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wu, G. In situ hybridization assay for circular RNA visualization based on padlock probe and rolling circle amplification. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 610, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, J.; Baird, A.-M.; Brady, L.; Lim, M.; Gray, S.G.; McDermott, R.; Finn, S.P. Circular RNAs: Biogenesis, function and role in human diseases. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2017, 4, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wei, C.; Xie, Y.; Su, Y.; Liu, C.; Qiu, G.; Liu, W.; Liang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Huang, D. Expanded insights into the mechanisms of RNA-binding protein regulation of circRNA generation and function in cancer biology and therapy. Genes Dis. 2025, 12, 101383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Yang, T.; Chen, Q.; Yuan, H.; Wu, P.; Cai, B.; Meng, L.; Huang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y. CircNEIL3 regulatory loop promotes pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma progression via miRNA sponging and A-to-I RNA-editing. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yao, J.; Shi, H.; Gao, B.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, D.; Gao, S.; Wang, C.; Zhang, L. Hsa_circ_0026628 promotes the development of colorectal cancer by targeting SP1 to activate the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, L.; Wu, P.; Li, X.; Tang, Y.; Ou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Wang, J.; Tang, H. The circROBO1/KLF5/FUS feedback loop regulates the liver metastasis of breast cancer by inhibiting the selective autophagy of afadin. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Wang, X.; Yang, F.; Zang, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Xu, X.; Li, W.; Jia, J.; Liu, Z. Circular RNA hsa_circ_0004872 inhibits gastric cancer progression via the miR-224/Smad4/ADAR1 successive regulatory circuit. Mol. Cancer 2020, 19, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, B.; Mao, Q.; Xia, W.; Zhang, T.; Song, X.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, L.; Dong, G. circDCUN1D4 suppresses tumor metastasis and glycolysis in lung adenocarcinoma by stabilizing TXNIP expression. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2021, 23, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Lan, T.; Li, H.; Xu, L.; Chen, X.; Liao, H.; Chen, X.; Du, J.; Cai, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Circular RNA circDLC1 inhibits MMP1-mediated liver cancer progression via interaction with HuR. Theranostics 2021, 11, 1396–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, Z.; Lu, Y.; Wan, X.; Luo, J.; Li, D.; Huang, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y. Comprehensive characterization of androgen-responsive circRNAs in prostate cancer. Life 2021, 11, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conn, S.J.; Pillman, K.A.; Toubia, J.; Conn, V.M.; Salmanidis, M.; Phillips, C.A.; Roslan, S.; Schreiber, A.W.; Gregory, P.A.; Goodall, G.J. The RNA binding protein quaking regulates formation of circRNAs. Cell 2015, 160, 1125–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.; Hao, S.; Jiang, L.; Cai, Y.; Zhao, X.; Chen, Q.; Gao, X.; Xu, J. CRIT: Identifying RNA-binding protein regulator in circRNA life cycle via non-negative matrix factorization. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2022, 30, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Pan, X.; Yang, Y.; Shen, H.B. CRIP: Predicting circRNA-RBP-binding sites using a codon-based encoding and hybrid deep neural networks. RNA 2019, 25, 1604–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Yuan, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, H. CircSLNN: Identifying RBP-Binding Sites on circRNAs via Sequence Labeling Neural Networks. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Yang, Y. DeCban: Prediction of circRNA-RBP Interaction Sites by Using Double Embeddings and Cross-Branch Attention Networks. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 632861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muppirala, U.K.; Honavar, V.G.; Dobbs, D. Predicting RNA-protein interactions using only sequence information. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, V.; Liu, L.; Adjeroh, D.; Zhou, X. RPI-Pred: Predicting ncRNA-protein interaction using sequence and structural information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 1370–1379. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Paz, I.; Kosti, I.; Ares, M., Jr.; Cline, M.; Mandel-Gutfreund, Y. RBPmap: A web server for mapping binding sites of RNA-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, W361–W367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, F.C.; Ule, J. Advances in CLIP technologies for studies of protein-RNA interactions. Mol. Cell 2018, 69, 354–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafner, M.; Landthaler, M.; Burger, L.; Khorshid, M.; Hausser, J.; Berninger, P.; Rothballer, A.; Ascano, M.; Jungkamp, A.-C.; Munschauer, M. Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell 2010, 141, 129–141. [Google Scholar]

- Ulshöfer, C.J.; Pfafenrot, C.; Bindereif, A.; Schneider, T. Methods to study circRNA-protein interactions. Methods 2021, 196, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogell, B.; Fischer, B.; Rettel, M.; Krijgsveld, J.; Castello, A.; Hentze, M.W. Specific RNP capture with antisense LNA/DNA mixmers. RNA 2017, 23, 1290–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, A.; Thomas, M.P.; Altschuler, G.; Navarro, F.; O’Day, E.; Li, X.L.; Concepcion, C.; Han, Y.-C.; Thiery, J.; Rajani, D.K. Capture of microRNA–bound mRNAs identifies the tumor suppressor miR-34a as a regulator of growth factor signaling. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Bao, C.; Guo, W.; Li, S.; Chen, J.; Chen, B.; Luo, Y.; Lyu, D.; Li, Y.; Shi, G. Circular RNA profiling reveals an abundant circHIPK3 that regulates cell growth by sponging multiple miRNAs. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Jing, B.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, H. Circular RNA circTMEM45A Acts as the Sponge of MicroRNA-665 to Promote Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2020, 22, 285–297. [Google Scholar]

- He, Q.; Yan, D.; Dong, W.; Bi, J.; Huang, L.; Yang, M.; Huang, J.; Qin, H.; Lin, T. circRNA circFUT8 Upregulates Krüpple-like Factor 10 to Inhibit the Metastasis of Bladder Cancer via Sponging miR-570-3p. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2020, 16, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Ren, F.; Sun, D.; Yan, Y.; Kong, X.; Bu, J.; Liu, M.; Xu, S. circRNA-002178 act as a ceRNA to promote PDL1/PD1 expression in lung adenocarcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obi, P.; Chen, Y.G. The design and synthesis of circular RNAs. Methods 2021, 19, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, M.; Deng, X.; Chen, Z.; Hu, Y. Circular RNA circPOFUT1 enhances malignant phenotypes and autophagy-associated chemoresistance via sequestrating miR-488-3p to activate the PLAG1-ATG12 axis in gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Dai, X.; Zhou, T.; Chen, J.; Tao, B.; Zhang, J.; Cao, F. The tumor-suppressive human circular RNA CircITCH sponges miR-330-5p to ameliorate doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity through upregulating SIRT6, survivin, and SERCA2a. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, e108–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Huang, V.; Xu, X.; Livingstone, J.; Soares, F.; Jeon, J.; Zeng, Y.; Hua, J.T.; Petricca, J.; Guo, H. Widespread and functional RNA circularization in localized prostate cancer. Cell 2019, 176, 831–843.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xiong, F.; Yan, Q.; Jiang, X.; Deng, X.; Wang, Y.; Fan, C.; Tang, L.; et al. Circular RNA circRNF13 inhibits proliferation and metastasis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma via SUMO2. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, D.D.; Senzer, N.; Cleary, M.A.; Nemunaitis, J. Comparative assessment of siRNA and shRNA off target effects: What is slowing clinical development. Cancer Gene Ther. 2009, 16, 807–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Gao, D.; Xu, T.; Zhang, L.; Tong, X.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.; Ning, W.; Qi, X.; Ma, Y.; et al. Circular RNA profiling in the oocyte and cumulus cells reveals that circARMC4 is essential for porcine oocyte maturation. Aging 2019, 11, 8015–8034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welden, J.R.; Margvelani, G.; Miaro, M.; Mathews, D.; Rodgers, D.W.; Stamm, S. An oligo walk to identify siRNAs against the circular Tau 12-> 7 RNA. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, B.; Zhou, M.; Fan, F.; Yu, M.; Gao, C.; Lu, Y.; Luo, Y. Circular RNA HIPK3 regulates human lens epithelial cells proliferation and apoptosis by targeting the miR-193a/CRYAA axis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 503, 2277–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsushima, K.; Pokhrel, R.; Mahmud, I.; Yuan, M.; Murad, R.; Baral, P.; Zhou, R.; Chapagain, P.; Garrett, T.; Stapleton, S.; et al. The oncogenic circular RNA circ_63706 is a potential therapeutic target in sonic hedgehog-subtype childhood medulloblastomas. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2023, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Keefe, E.P. siRNAs and shRNAs: Tools for protein knockdown by gene silencing. Mater. Methods 2013, 3, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamudurti, N.R.; Patop, I.L.; Krishnamoorthy, A.; Ashwal-Fluss, R.; Bartok, O.; Kadener, S. An in vivo strategy for knockdown of circular RNAs. Cell Discov. 2020, 6, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.-D.; Jiang, Q.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Q.-Y.; Shi, Z.-H.; Zhao, C.; Yan, B. Targeting circular RNA-MET for anti-angiogenesis treatment via inhibiting endothelial tip cell specialization. Mol. Ther. 2022, 30, 1252–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-X.; Lu, J.; Xie, H.; Wang, D.-P.; Ni, H.-E.; Zhu, Y.; Ren, L.-H.; Meng, X.-X.; Wang, R.-L. circHIPK3 regulates lung fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition by functioning as a competing endogenous RNA. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwecka, M.; Glažar, P.; Hernandez-Miranda, L.R.; Memczak, S.; Wolf, S.A.; Rybak-Wolf, A.; Filipchyk, A.; Klironomos, F.; Jara, C.A.C.; Fenske, P. Loss of a mammalian circular RNA locus causes miRNA deregulation and affects brain function. Science 2017, 357, eaam8526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xue, W.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Zhang, J.-L.; Yang, L.; Chen, L.-L. The Biogenesis of Nascent Circular RNAs. Cell Rep. 2016, 15, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Ma, X.-K.; Li, X.; Li, G.-W.; Liu, C.-X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wei, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, L.-L. Knockout of circRNAs by base editing back-splice sites of circularized exons. Genome Biol. 2022, 23, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.X.; Chong, S.; Zhang, H.; Makarova, K.S.; Koonin, E.V.; Cheng, D.R.; Scott, D.A. Cas13d Is a Compact RNA-Targeting Type VI CRISPR Effector Positively Modulated by a WYL-Domain-Containing Accessory Protein. Mol. Cell 2018, 70, 327–339.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, X.; Xue, W.; Zhang, L.; Yang, L.-Z.; Cao, S.-M.; Lei, Y.-N.; Liu, C.-X.; Guo, S.-K.; Shan, L.; et al. Screening for functional circular RNAs using the CRISPR–Cas13 system. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, H.; An, O.; Ren, X.; Song, Y.; Tang, S.J.; Ke, X.-Y.; Han, J.; Tay, D.J.T.; Ng, V.H.E.; Molias, F.B. ADARs act as potent regulators of circular transcriptome in cancer. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.; Yu, J.; Guo, L.; Ma, H. Circular RNA circRHOT1 contributes to pathogenesis of non-small cell lung cancer by epigenetically enhancing C-MYC expression through recruiting KAT5. Aging 2021, 13, 20372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, P.-W.; Huang, H.-T.; Ma, J.; Zuo, Y.; Huang, D.; He, L.-L.; Wan, Z.-M.; Chen, C.; Yang, F.-F.; You, Y.-W. Circular RNA-0007059 protects cell viability and reduces inflammation in a nephritis cell model by inhibiting microRNA-1278/SHP-1/STAT3 signaling. Mol. Med. 2021, 27, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, W.; Guo, X. Overexpression of circular RNA hsa_circ_0001038 promotes cervical cancer cell progression by acting as a ceRNA for miR-337-3p to regulate cyclin-M3 and metastasis-associated in colon cancer 1 expression. Gene 2020, 733, 144273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Luo, L.; Gao, Y. Circular RNA PVT1 enhances cell proliferation but inhibits apoptosis through sponging microRNA-149 in epithelial ovarian cancer. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2020, 46, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chakravarthi, V.P.; Christenson, L.K. Wet Lab Techniques for the Functional Analysis of Circular RNA. Cells 2025, 14, 1920. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231920

Chakravarthi VP, Christenson LK. Wet Lab Techniques for the Functional Analysis of Circular RNA. Cells. 2025; 14(23):1920. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231920

Chicago/Turabian StyleChakravarthi, V. Praveen, and Lane K. Christenson. 2025. "Wet Lab Techniques for the Functional Analysis of Circular RNA" Cells 14, no. 23: 1920. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231920

APA StyleChakravarthi, V. P., & Christenson, L. K. (2025). Wet Lab Techniques for the Functional Analysis of Circular RNA. Cells, 14(23), 1920. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231920