New Biomarkers in the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Pro-Resolving Lipids and miRNAs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Human Samples

2.2. CRP Determination

2.3. LXA4 and RvD1 Quantification

2.4. miRNA Profiling in Human Serum via TLDA

2.5. miRNA Validation by qPCR Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

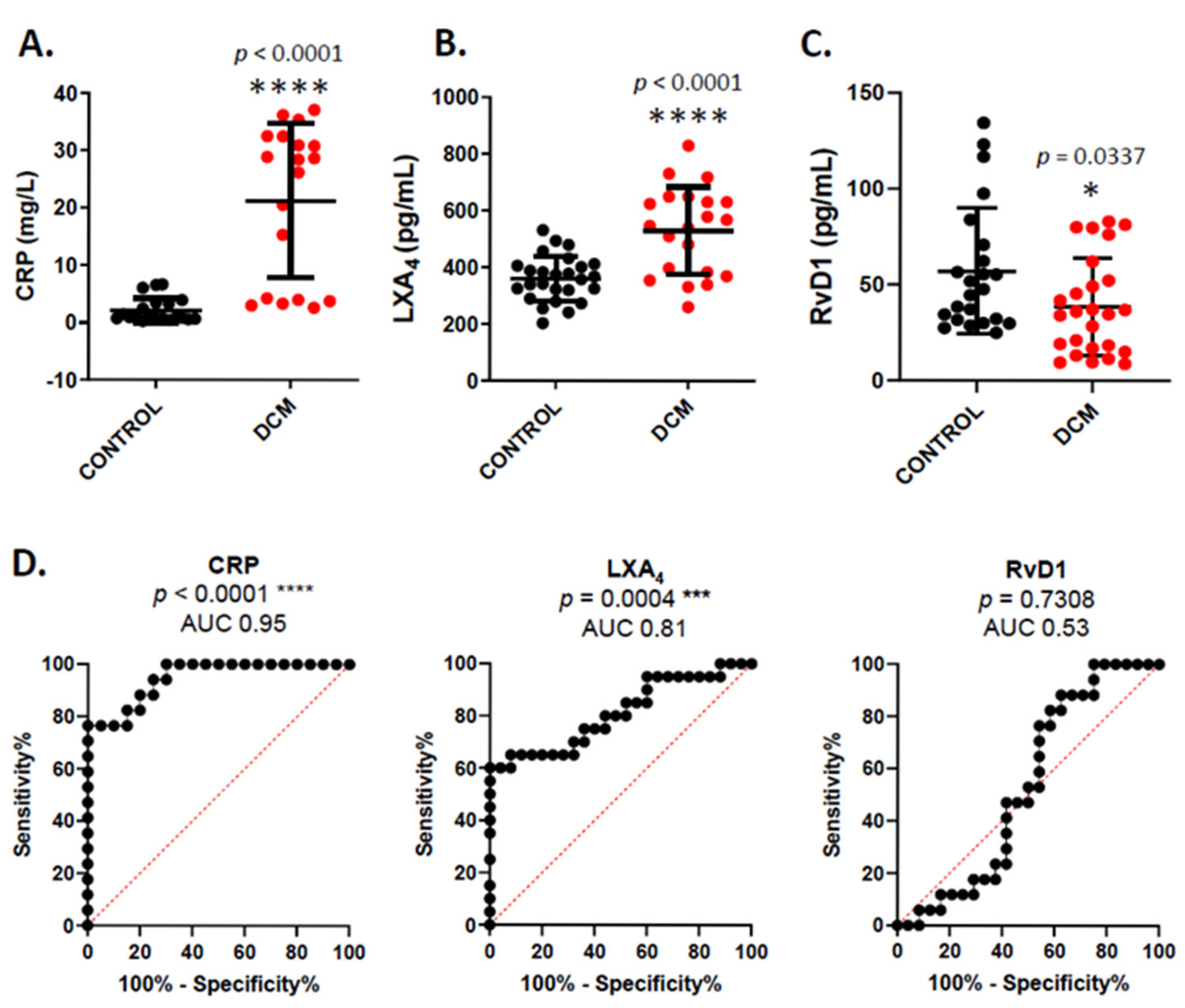

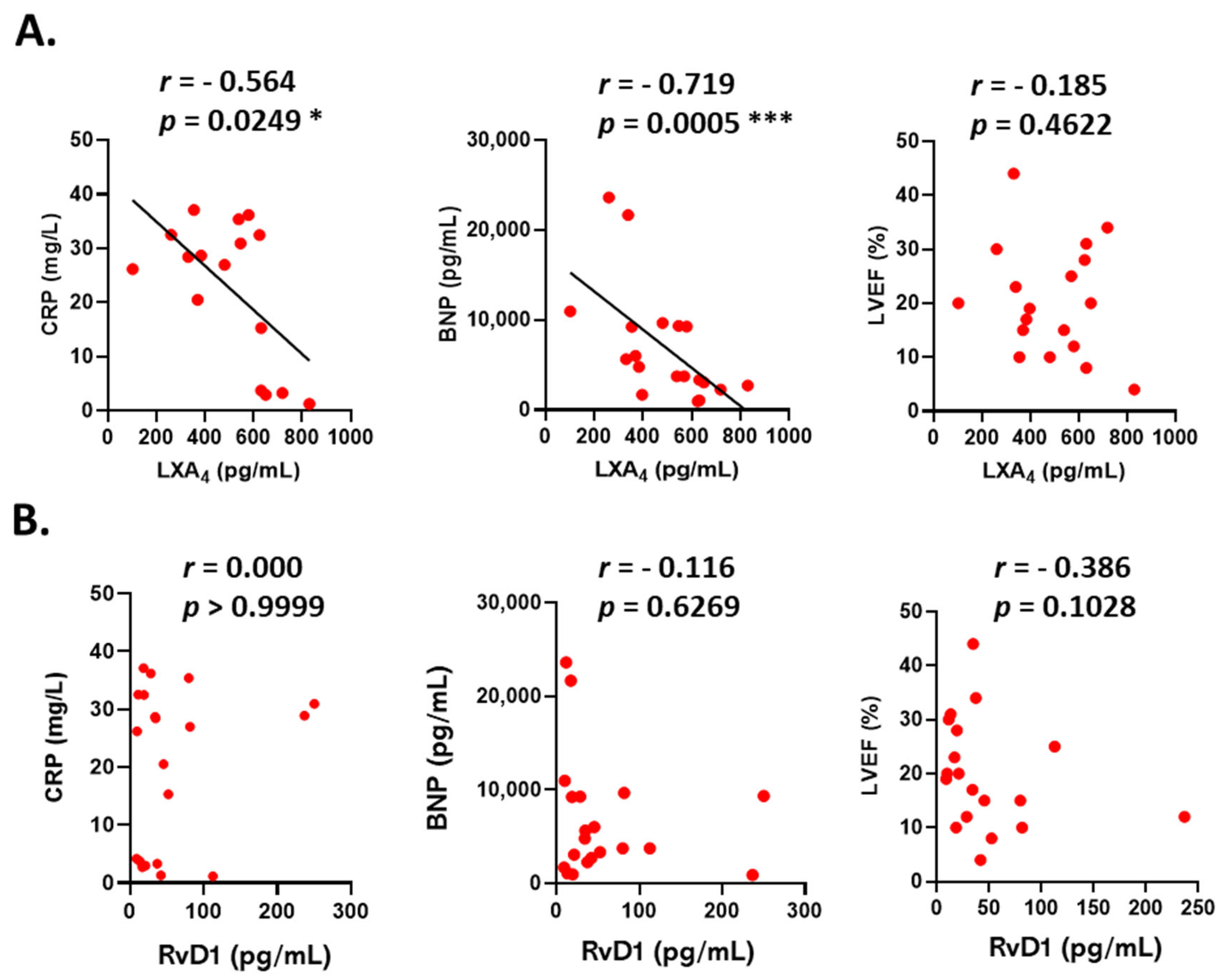

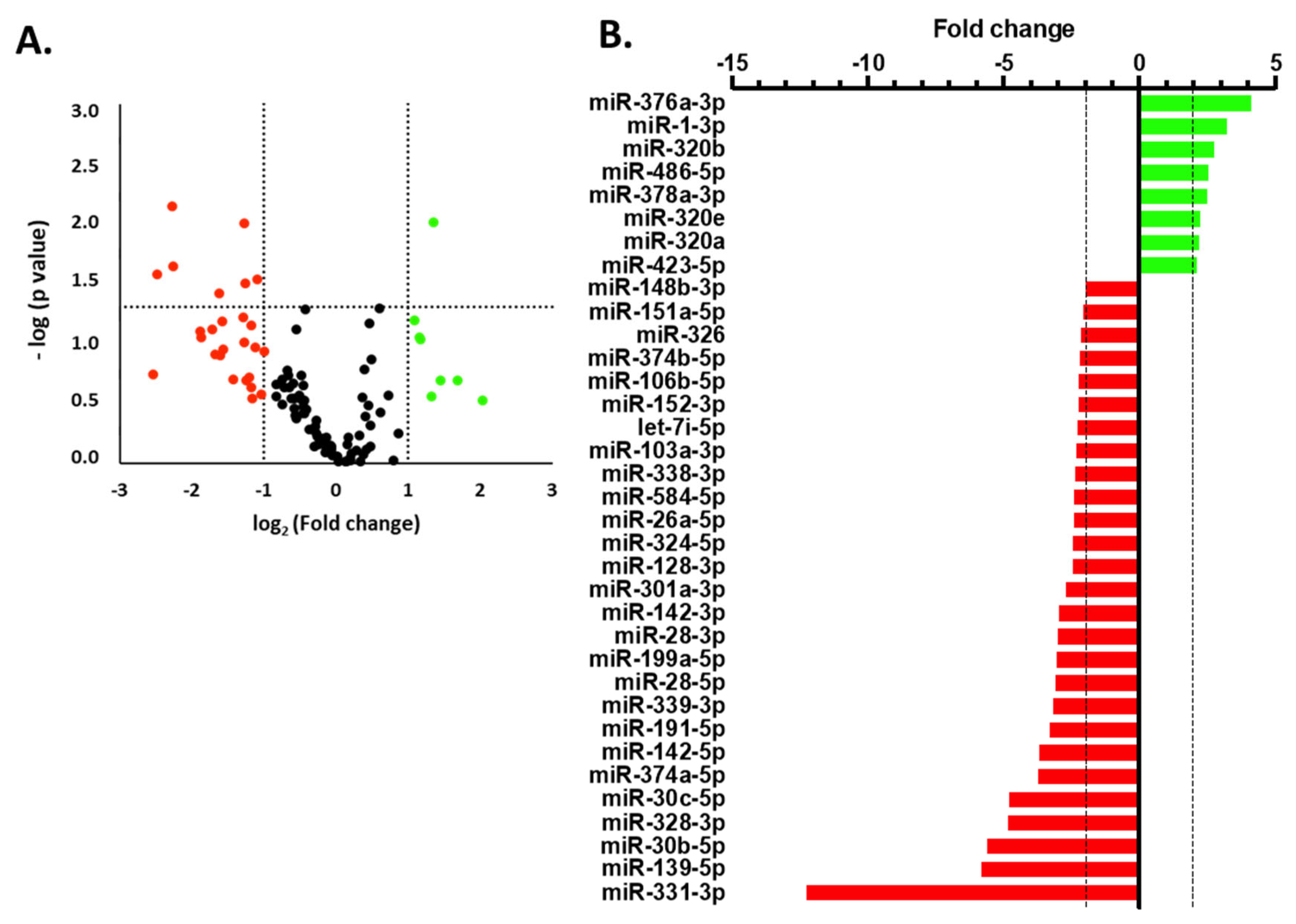

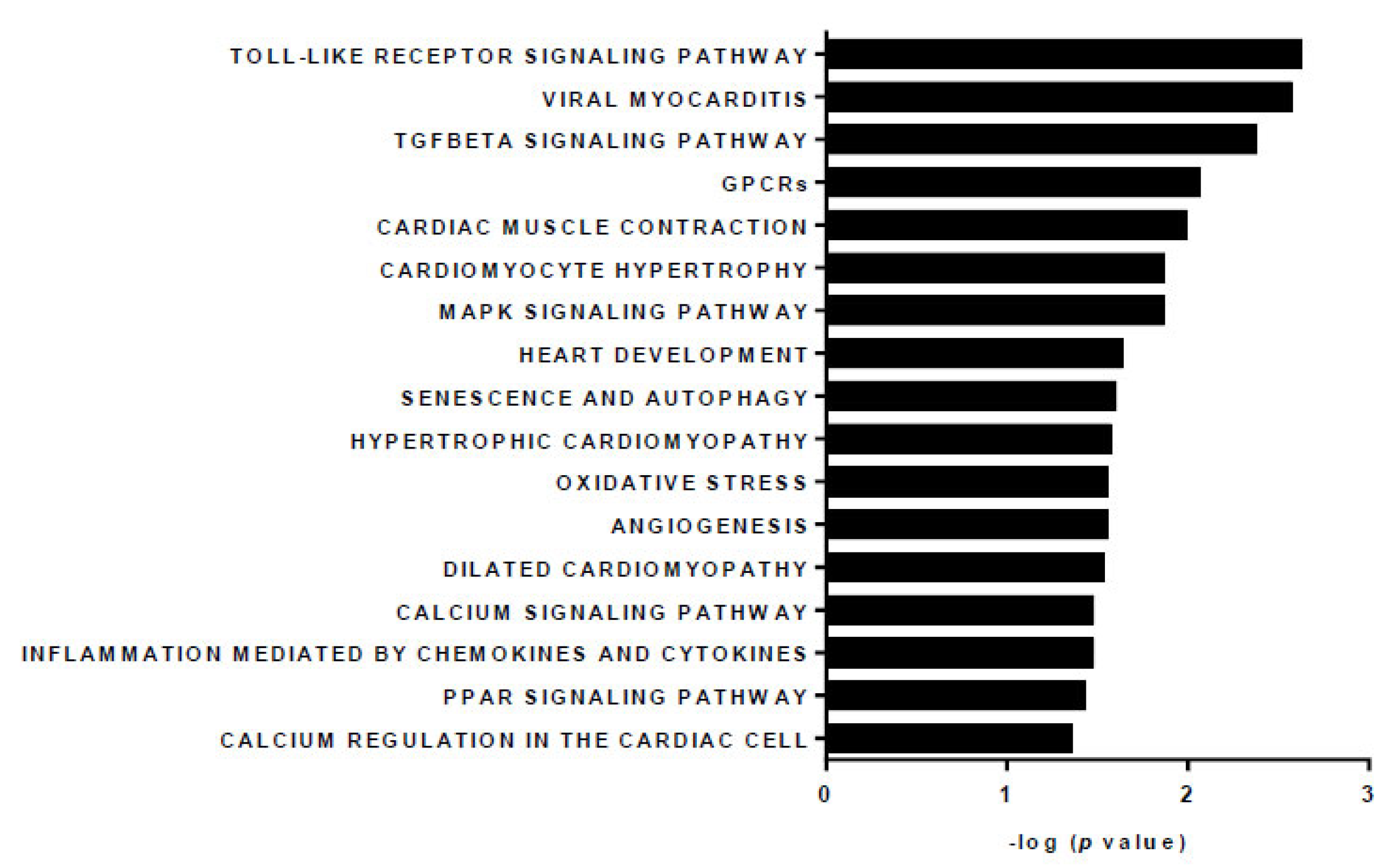

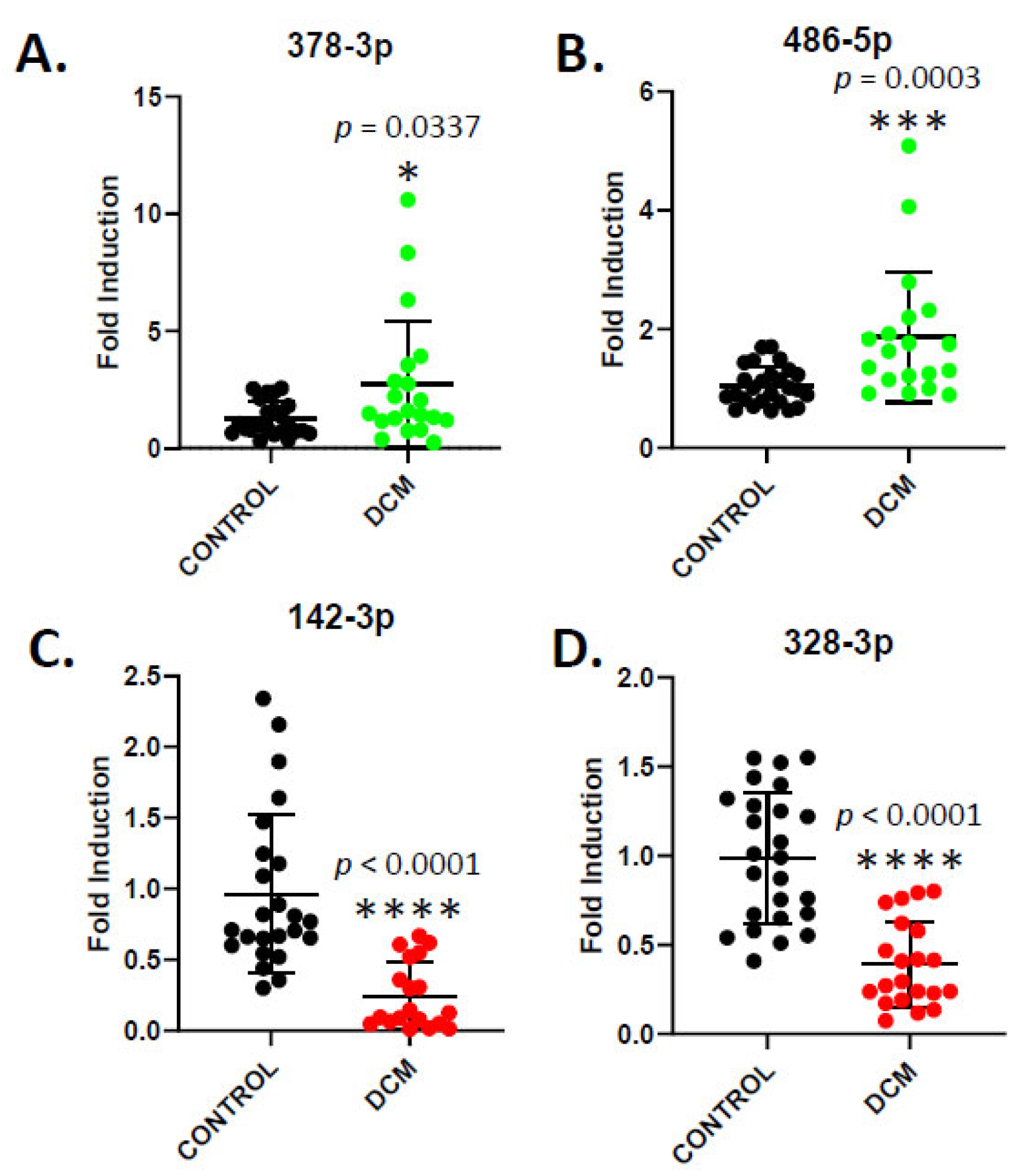

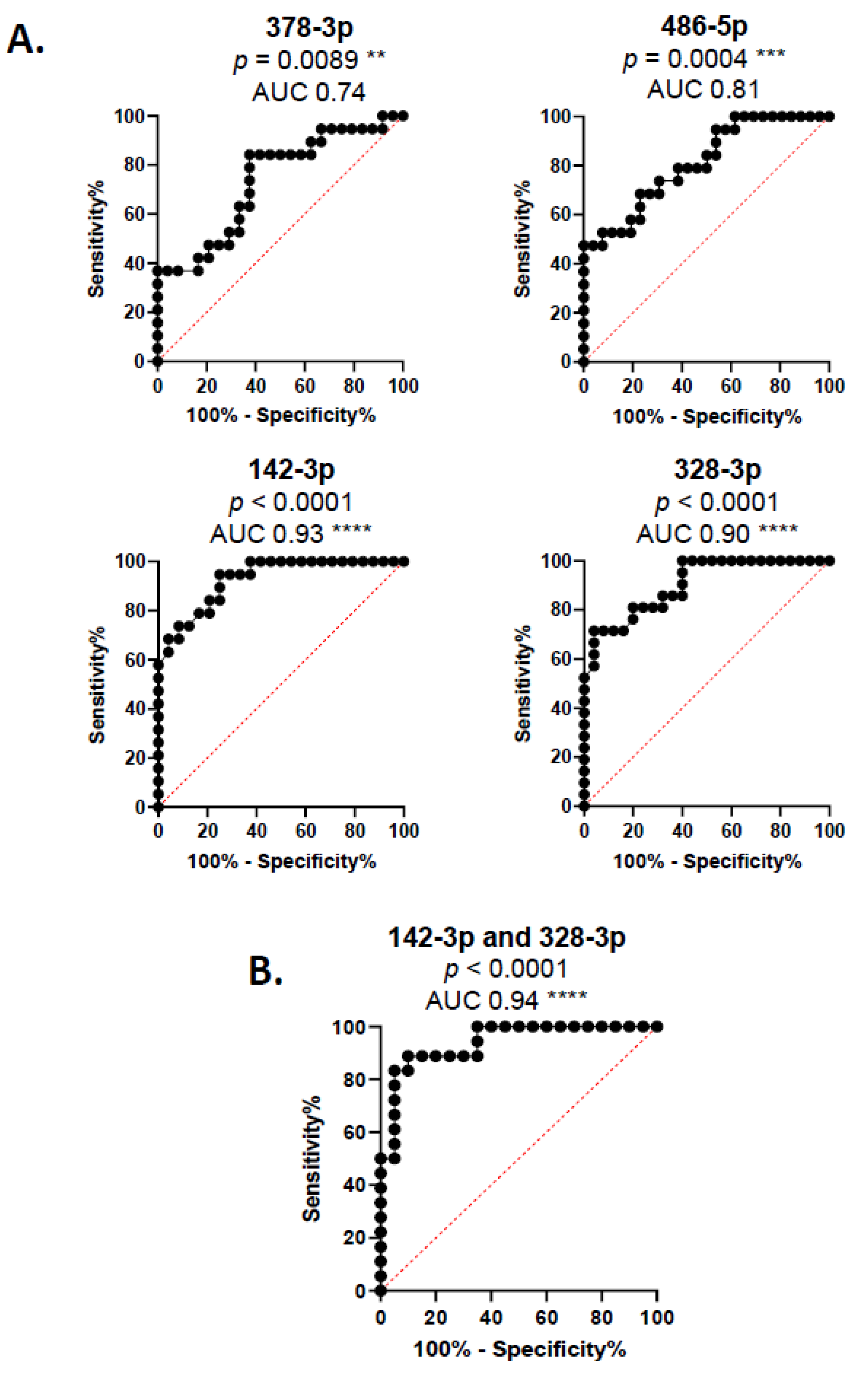

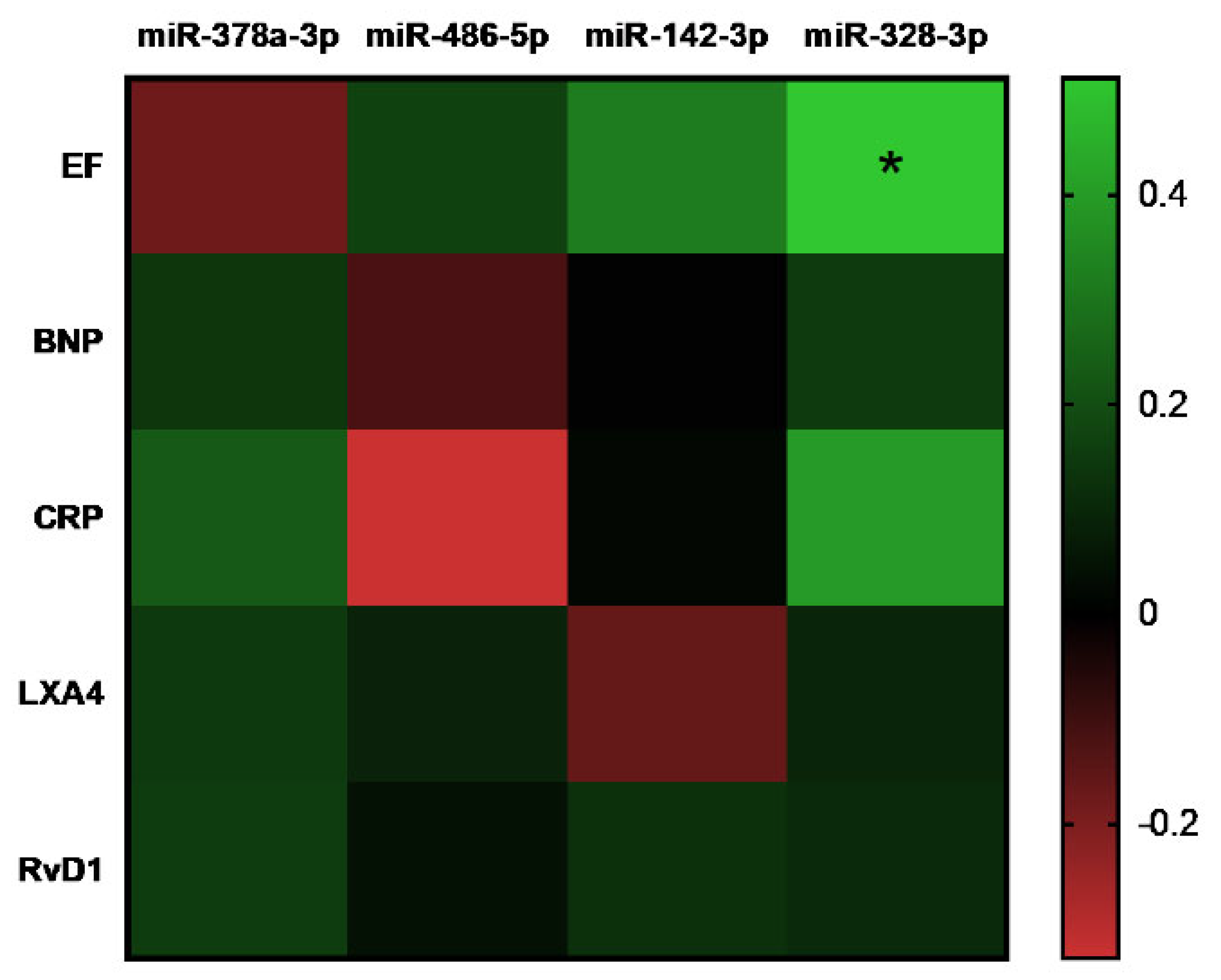

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gigli, M.; Stolfo, D.; Merlo, M.; Sinagra, G.; Taylor, M.R.G.; Mestroni, L. Pathophysiology of dilated cardiomyopathy: From mechanisms to precision medicine. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2025, 22, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymans, S.; Lakdawala, N.K.; Tschöpe, C.; Klingel, K. Dilated cardiomyopathy: Causes, mechanisms, and current and future treatment approaches. Lancet 2023, 402, 998–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mestroni, L.; Brun, F.; Spezzacatene, A.; Sinagra, G.; Taylor, M.R.G. Genetic causes of dilated cardiomyopathy. Prog. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2014, 37, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieczorek, D. Dilated Cardiomyopathy—Exploring the Underlying Causes. Med. Res. Arch. 2024, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, H.; Cao, J.; Kinnamon, D.D.; Jordan, E.; Haas, G.J.; Hofmeyer, M.; Kransdorf, E.P.; Diamond, J.; Owens, A.; Lowes, B.; et al. Antecedent Flu-Like Illness and Onset of Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy: The DCM Precision Medicine Study. Circ. Heart Fail. 2025, 18, e012602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orphanou, N.; Papatheodorou, E.; Anastasakis, A. Dilated cardiomyopathy in the era of precision medicine: Latest concepts and developments. Heart Fail. Rev. 2022, 27, 1173–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, N.A.; Burke, M.A. Dilated Cardiomyopathy: A Genetic Journey from Past to Future. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, C.; Gan, F.; Wang, Y.; Ding, L.; Hua, W. Plasma NT pro-BNP, hs-CRP and big-ET levels at admission as prognostic markers of survival in hospitalized patients with dilated cardiomyopathy: A single-center cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2014, 14, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, K.; Kanda, T.; Yamauchi, Y.; Hasegawa, A.; Iwasaki, T.; Arai, M.; Suzuki, T.; Kobayashi, I.; Nagai, R. C-Reactive protein in dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiology 1999, 91, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, C.; Tsutamoto, T.; Fujii, M.; Sakai, H.; Tanaka, T.; Horie, M. Prediction of mortality by high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and brain natriuretic peptide in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ. J. 2006, 70, 857–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N. Pro-resolving lipid mediators are leads for resolution physiology. Nature 2014, 510, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaén, R.I.; Fernández-Velasco, M.; Terrón, V.; Sánchez-García, S.; Zaragoza, C.; Canales-Bueno, N.; Val-Blasco, A.; Vallejo-Cremades, M.T.; Boscá, L.; Prieto, P. BML-111 treatment prevents cardiac apoptosis and oxidative stress in a mouse model of autoimmune myocarditis. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 10531–10546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.; Mohan, M.; Bose, M.; Brennan, E.P.; Kiriazis, H.; Deo, M.; Nowell, C.J.; Godson, C.; Cooper, M.E.; Zhao, P.; et al. Lipoxin A4 improves cardiac remodeling and function in diabetes-associated cardiac dysfunction. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kain, V.; Liu, F.; Kozlovskaya, V.; Ingle, K.A.; Bolisetty, S.; Agarwal, A.; Khedkar, S.; Prabhu, S.D.; Kharlampieva, E.; Halade, G.V. Resolution Agonist 15-epi-Lipoxin A4 Programs Early Activation of Resolving Phase in Post-Myocardial Infarction Healing. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saqib, U.; Pandey, M.; Vyas, A.; Patidar, P.; Hajela, S.; Ali, A.; Tiwari, M.; Sarkar, S.; Yadav, N.; Patel, S.; et al. Lipoxins as Modulators of Diseases. Cells 2025, 14, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Li, J.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, N.; Liu, W.; Liu, C.; Zhou, P.; Chen, Y.; et al. Prognostic impacts of Lipoxin A4 in patients with acute myocardial infarction: A prospective cohort study. Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 187, 106618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Jiang, F.; Xu, W.; He, P.; Chen, F.; Liu, X.; Bao, X. Declined Serum Resolvin D1 Levels to Predict Severity and Prognosis of Human Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Prospective Cohort Study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2023, 19, 1463–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karayiǧit, O.; Nurkoç, S.G.; Başyiǧit, F.; Klzlltunç, E. The Role of Serum Resolvin D1 Levels in Determining the Presence and Prognosis of ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Med. Princ. Pract. 2022, 31, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recchiuti, A.; Serhan, C.N. Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators (SPMs) and Their Actions in Regulating miRNA in Novel Resolution Circuits in Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 33069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredman, G.; Serhan, C.N. Specialized pro-resolving mediators in vascular inflammation and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2024, 21, 808–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyszkowski, R.; Mehrzad, R. Resolution of inflammation. In Inflammation and Obesity, A New and Novel Approach to Manage Obesity and Its Consequences; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, P.; Goławski, M.; Baron, M.; Reichman-Warmusz, E.; Wojnicz, R. A Systematic Review of miRNA and cfDNA as Potential Biomarkers for Liquid Biopsy in Myocarditis and Inflammatory Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiti, E.; Di Paolo, M.; Turillazzi, E.; Rocchi, A. Micrornas in hypertrophic, arrhythmogenic and dilated cardiomyopathy. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso-Villa, E.; Bonet, F.; Hernandez-Torres, F.; Campuzano, Ó.; Sarquella-Brugada, G.; Quezada-Feijoo, M.; Ramos, M.; Mangas, A.; Toro, R. The Role of MicroRNAs in Dilated Cardiomyopathy: New Insights for an Old Entity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Shi, J.; Wang, J.; Hu, Y. MicroRNA-378: An important player in cardiovascular diseases (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2023, 28, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Tian, L.; Yan, Z.; Wang, J.; Xue, T.; Sun, Q. Diagnostic and prognostic value of miR-486-5p, miR-451a, miR-21-5p and monocyte to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Heart Vessel. 2023, 38, 318–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwańczyk, S.; Lehmann, T.; Cieślewicz, A.; Malesza, K.; Woźniak, P.; Hertel, A.; Krupka, G.; Jagodziński, P.P.; Grygier, M.; Lesiak, M.; et al. Circulating miRNA-451a and miRNA-328-3p as Potential Markers of Coronary Artery Aneurysmal Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Guo, J. MicroRNA-328-3p Protects Vascular Endothelial Cells Against Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein Induced Injury via Targeting Forkhead Box Protein O4 (FOXO4) in Atherosclerosis. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26, e921877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, S.; Jaén, R.I.; Lozano-Rodríguez, R.; Avendaño-Ortiz, J.; Pascual-Iglesias, A.; Hurtado-Navarro, L.; López-Collazo, E.; Boscá, L.; Prieto, P. Lipoxin A4 levels correlate with severity in a Spanish COVID-19 cohort: Potential use of endogenous pro-resolving mediators as biomarkers. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1509188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perucci, L.O.; Santos, P.C.; Ribeiro, L.S.; Souza, D.G.; Gomes, K.B.; Dusse, L.M.S.; Sousa, L.P. Lipoxin A4 is increased in the plasma of preeclamptic women. Am. J. Hypertens. 2016, 29, 1179–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, J.; Liu, W.; Fang, Y.B.; Zhang, S.; Qiu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Huang, T.C.; Zhang, H.F.; Xie, Y.; et al. The atheroprotective role of lipoxin A4 prevents oxLDL-induced apoptotic signaling in macrophages via JNK pathway. Atherosclerosis 2018, 278, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yücel, H.; Özdemir, A.T. Low LXA4, RvD1 and RvE1 levels may be an indicator of the development of hypertension. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2021, 174, 102365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgül Özdemir, R.B.; Soysal Gündüz, Ö.; Özdemir, A.T.; Akgül, Ö. Low levels of pro-resolving lipid mediators lipoxin-A4, resolvin-D1 and resolvin-E1 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol. Lett. 2020, 227, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, S.; Sezer, S. Serum Maresin-1 and Resolvin-D1 Levels as Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Monitoring Disease Activity in Ulcerative Colitis. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zheng, W.; Liang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Sun, W.; Zhou, J.; Qiao, W.; Xie, Q.; Tang, R. Acute Coronary Syndrome May be Associated with Decreased Resolvin D1-to-Leukotriene B4 Ratio. Int. Heart J. 2023, 64, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reina-Couto, M.; Carvalho, J.; Valente, M.J.; Vale, L.; Afonso, J.; Carvalho, F.; Bettencourt, P.; Sousa, T.; Albino-Teixeira, A. Impaired resolution of inflammation in human chronic heart failure. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 44, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Hu, Z. Decreased plasma lipoxin A4, resolvin D1, protectin D1 are correlated with the complexity and prognosis of coronary heart disease: A retrospective cohort study. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2025, 178, 106990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Searles, C.D. MicroRNAs and Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2024, 26, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobescu, L.; Ciobanu, A.O.; Macarie, R.; Vadana, M.; Ciortan, L.; Tucureanu, M.M.; Butoi, E.; Simionescu, M.; Vinereanu, D. Diagnostic and Prognostic Role of Circulating microRNAs in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease-Impact on Left Ventricle and Arterial Function. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 8499–8511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahul, K.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, B.; Chaudhary, V.; Rahul, K.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, B.; Chaudhary, V. Circulating microRNAs as potential novel biomarkers in cardiovascular diseases: Emerging role, biogenesis, current knowledge, therapeutics and the road ahead. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Acad. 2022, 8, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.X.; Norling, L.V.; Vecchio, E.A.; Brennan, E.P.; May, L.T.; Wootten, D.; Godson, C.; Perretti, M.; Ritchie, R.H. Formylpeptide receptor 2: Nomenclature, structure, signalling and translational perspectives: IUPHAR review 35. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 179, 4617–4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yao, K.; Wise, A.F.; Lau, R.; Shen, H.H.; Tesch, G.H.; Ricardo, S.D. miR-378 reduces mesangial hypertrophy and kidney tubular fibrosis via MAPK signalling. Clin. Sci. 2017, 131, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y. MiR-486-5p inhibits the hyperproliferation and production of collagen in hypertrophic scar fibroblasts via IGF1/PI3K/AKT pathway. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2021, 32, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ouyang, J.; Feng, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C.; Tan, L.; Zhong, J.; et al. MicroRNA-142-3P suppresses the progression of papillary thyroid carcinoma by targeting FN1 and inactivating FAK/ERK/PI3K signaling. Cell. Signal. 2023, 109, 110792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, S.; Ren, F.; Li, L.; Liu, D.; Li, Y.; Wang, A.; Li, W.; Dong, Y.; Guo, W. MiR-328-3p inhibits cell proliferation and metastasis in colorectal cancer by targeting Girdin and inhibiting the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Exp. Cell Res. 2020, 390, 111939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wei, C.; Zhao, L.; Guo, X.; Cui, X.; Shao, L.; Long, J.; Gu, J.; Zhao, M. MiR-378 modulates energy imbalance and apoptosis of mitochondria induced by doxorubicin. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2018, 10, 3600. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Feng, L.; Liu, C.; Han, Z.; Chen, X. MiR-378 Inhibits Angiotensin II-Induced Cardiomyocyte Hypertrophy by Targeting AKT2. Int. Heart J. 2024, 65, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, J.; Ramanujam, D.; Sassi, Y.; Ahles, A.; Jentzsch, C.; Werfel, S.; Leierseder, S.; Loyer, X.; Giacca, M.; Zentilin, L.; et al. MiR-378 controls cardiac hypertrophy by combined repression of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway factors. Circulation 2013, 127, 2097–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knezevic, I.; Patel, A.; Sundaresan, N.R.; Gupta, M.P.; Solaro, R.J.; Nagalingam, R.S.; Gupta, M. A novel cardiomyocyte-enriched MicroRNA, miR-378, targets insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor: Implications in postnatal cardiac remodeling and cell survival. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 12913–12926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Jabbar Ali1, S.; Al-Shlah, H.H.; Al-Hamdani, M.M. Evaluating the Sensitivity of (miR-378) as a Circulatory Screening Biomarker for Diabetic Cardiomyopathy: Comparative Study. Med. Leg. Updat. 2021, 21, 912–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Yu, Y. MiR-486 alleviates hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced H9c2 cell injury by regulating forkhead box D3. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Su, Q.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Lu, Y.; Liang, J. MiR-486 regulates cardiomyocyte apoptosis by p53-mediated BCL-2 associated mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2017, 17, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hui, J. Exosomes of bone-marrow stromal cells inhibit cardiomyocyte apoptosis under ischemic and hypoxic conditions via miR-486-5p targeting the PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Thromb. Res. 2019, 177, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bei, Y.; Lu, D.; Bär, C.; Chatterjee, S.; Costa, A.; Riedel, I.; Mooren, F.C.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Wei, M.; et al. miR-486 attenuates cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury and mediates the beneficial effect of exercise for myocardial protection. Mol. Ther. 2022, 30, 1675–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; He, W.; Liang, J.; Mo, B.; Li, L. MicroRNA-486-5p targeting PTEN Protects Against Coronary Microembolization-Induced Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis in Rats by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 855, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xu, Y.; Lv, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, K.; Ni, C.; Wang, K.; Kong, M.; et al. Small extracellular vesicles containing miR-486-5p promote angiogenesis after myocardial infarction in mice and nonhuman primates. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabb0202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douvris, A.; Viñas, J.; Burns, K.D. miRNA-486-5p: Signaling targets and role in non-malignant disease. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, N.; Kumar, S.; Gongora, E.; Gupta, S. Circulating miRNA as novel markers for diastolic dysfunction. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2013, 376, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Cheng, M.; Hu, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Tu, X.; Huang, C.; Jiang, H.; Wu, G. Overexpression of miR-142-3p improves mitochondrial function in cardiac hypertrophy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 108, 1347–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Lv, X.; Ye, Z.; Sun, Y.; Kong, B.; Qin, Z.; Li, L. The mechanism of miR-142-3p in coronary microembolization-induced myocardiac injury via regulating target gene IRAK-1. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Chen, H.; Liang, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, C.; Moorthy, B.T. Upregulated miR-328-3p and its high risk in atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis with meta-regression. Medicine 2022, 101, E28980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wang, F.; Sun, X.; Chu, X.; Jiang, R.; Wang, Y.; Pang, L. Myocardial infarction cardiomyocytes-derived exosomal miR-328-3p promote apoptosis via Caspase signaling. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2021, 13, 2365. [Google Scholar]

| miRNA | miRBase Accession Number | Mature miRNA Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| Hsa-miR-142-3p | MIMAT0000434 | UGUAGUGUUUCCUACUUUAUGGA |

| Hsa-miR-328-3p | MIMAT0000752 | CUGGCCCUCUCUGCCCUUCCGU |

| Hsa-miR-378a-3p | MIMAT0000732 | ACUGGACUUGGAGUCAGAAGGC |

| Hsa-miR-486-5p | MIMAT0002177 | UCCUGUACUGAGCUGCCCCGAG |

| A | ||

| Healthy donors (N = 26) | DCM (N = 21) | |

| Age, mean ± SD (years) | 50.23 ± 9.58 | 53.4 ± 13.45 |

| Age, min–max (years) | 29–65 | 19–67 |

| B | ||

| DCM | ||

| PRO-BNP (pg/mL) | 4908.1 ± 3390 | |

| LVEF | ≤20% | 13 |

| 20–44% | 7 | |

| NOT DATA | 1 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jaén, R.I.; Sánchez-García, S.; Fernández-Velasco, M.; Cuadrado, I.; de las Heras, B.; Boscá, L.; Prieto, P. New Biomarkers in the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Pro-Resolving Lipids and miRNAs. Cells 2025, 14, 1916. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231916

Jaén RI, Sánchez-García S, Fernández-Velasco M, Cuadrado I, de las Heras B, Boscá L, Prieto P. New Biomarkers in the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Pro-Resolving Lipids and miRNAs. Cells. 2025; 14(23):1916. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231916

Chicago/Turabian StyleJaén, Rafael I., Sergio Sánchez-García, María Fernández-Velasco, Irene Cuadrado, Beatriz de las Heras, Lisardo Boscá, and Patricia Prieto. 2025. "New Biomarkers in the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Pro-Resolving Lipids and miRNAs" Cells 14, no. 23: 1916. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231916

APA StyleJaén, R. I., Sánchez-García, S., Fernández-Velasco, M., Cuadrado, I., de las Heras, B., Boscá, L., & Prieto, P. (2025). New Biomarkers in the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Pro-Resolving Lipids and miRNAs. Cells, 14(23), 1916. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231916