Heat Shock Proteins in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The HSP Family: Characteristics and Classification of HSPs

3. The Role of HSPs in Cancer

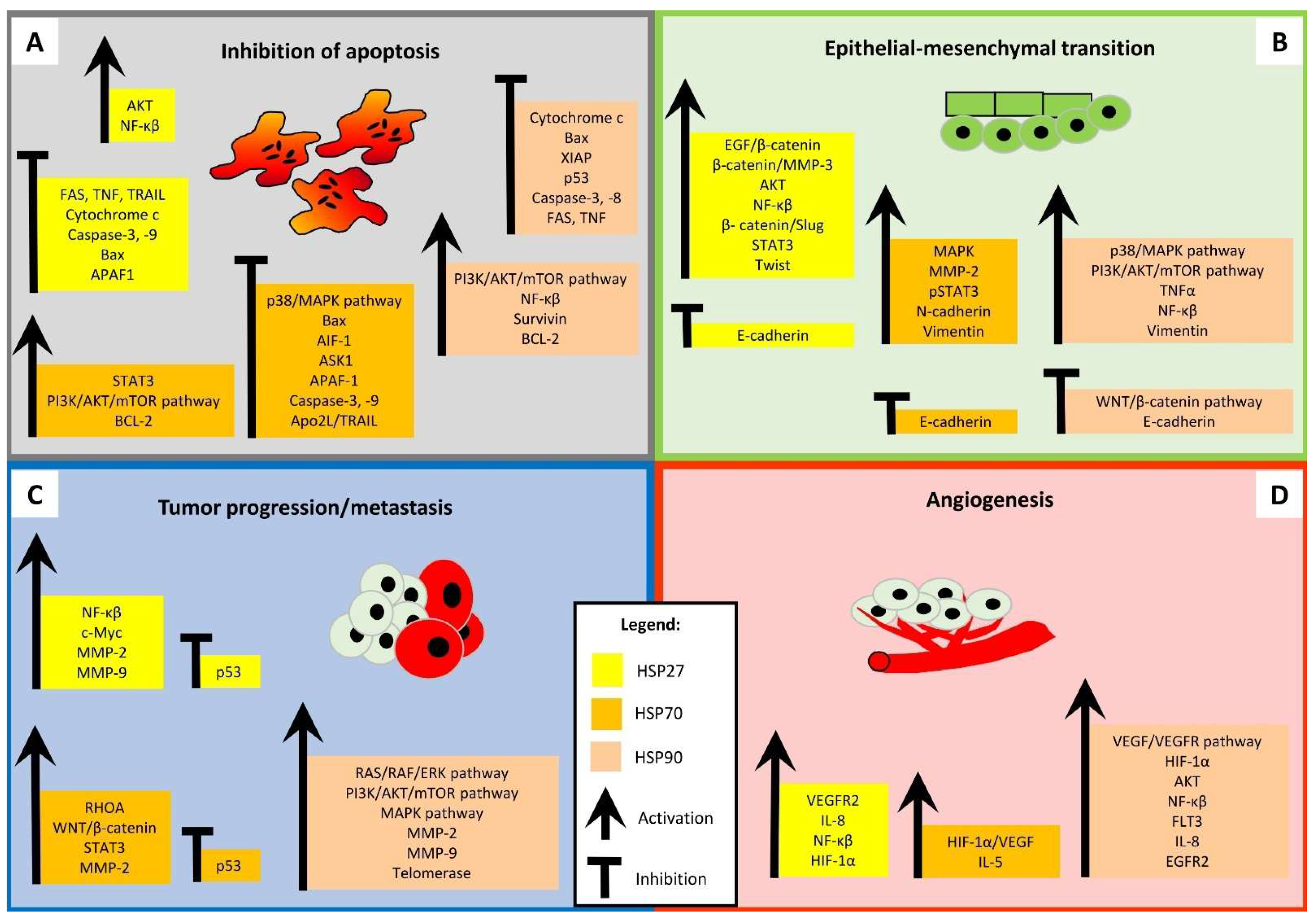

3.1. HSP27

3.2. HSP70

3.3. HSP90

4. The Clinicopathological and Prognostic Significance of HSPs in HNSCC

| HSP | Findings * | Method | Sample | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSP27 | Tumor site, lower pT stage | IHC | 50 | Gandour-Edwards et al., 1998 [60] |

| Better survival | IHC | 40 | Mese et al., 2002 [55] | |

| Better survival, lower tumor grade, older age | IHC, WB | 79 | Muzio et al., 2004 [56] | |

| Better OS, better prognosis | IHC | 57 | Muzio et al., 2006 [57] | |

| Better OS, better prognosis, lower tumor grade | IHC | 80 | Wang et al., 2009 [58] | |

| Early clinical stage, lower tumor grade | IHC | 56 | Mohtasham et al., 2011 [61] | |

| Worse OS, lymph node metastasis | IHC | 50 | Kaigorodova et al., 2016 [64] | |

| Higher clinical stage | IHC, PCR | 44 | Karam et al., 2017 [63] | |

| Higher tumor grade | IHC | 30 | Ajalyakeen et al., 2020 [62] | |

| Better OS, better prognosis, older age, higher pT stage, lymph node metastasis | IHC/TCGA | 158/112 | Borowczak et al., 2025 [59] | |

| HSP47 | Better OS, lower tumor grade | IHC, WB | 50 | Song et al., 2017 [65] |

| Worse OS | TCGA | 504 | Fan et al., 2020 [66] | |

| Worse survival, shorter DFS | IHC | 339 | Da Costa et al., 2023 [67] | |

| HSP60 | Worse OS | TCGA | 504 | Fan et al., 2020 [66] |

| Worse OS, poor prognosis, higher clinical stage, lymph node metastasis | IHC | 79 | Zhou et al., 2023 [68] | |

| HSP70 | Tumor size, tumor grade | IHC, WB | 38 | Kaur et al., 1995 [78] |

| Lower pT stage | IHC | 50 | Gandour-Edwards et al., 1998 [60] | |

| Shorter DFS, higher tumor grade, shorter transition time | IHC | 125 | Kaur et al., 1998 [69] | |

| Higher tumor grade, no lymph node metastasis | IHC | 41 | Lee et al., 2008 [70] | |

| Shorter DFS, tumor location, lymph node metastasis, tumor grade | IHC | 90 | Choi et al., 2015 [71] | |

| Lower clinical stage, no lymph node metastasis, smaller tumor size | IHC | 50 | Taghavi et al., 2018 [79] | |

| Higher tumor grade | IHC | 15 | Priyanka et al., 2019 [40] | |

| Older age | IHC | 117 | Venugopal et al., 2022 [80] | |

| Worse survival, poor prognosis, higher clinical stage, pT stage | IHC | 104 | Ceylan et al., 2022 [72] | |

| Higher TNM stage, higher tumor grade, lymph node metastasis, higher recurrence rate, shorter DFS, larger tumor size | IHC | 50 | Elhendawy et al., 2023 [22] | |

| Better OS, higher tumor grade | IHC/TCGA | 158/112 | Borowczak et al., 2025 [59] | |

| HSP90 | Lymph node metastasis, worse survival | IHC | 36 | Chang et al., 2017 [74] |

| Worse survival | WB | 499 | Ono et al., 2018 [50] | |

| Worse OS | TCGA | 504 | Fan et al., 2020 [66] | |

| Lymph node metastasis | IHC | 58 | Shiraishi et al., 2021 [12] | |

| Worse survival | IHC/TCGA | 97/98 | Santos et al., 2021 [76] | |

| Higher pT stage, survival status, poor prognosis | IHC | 56 | Bar et al., 2021 [73] | |

| Worse OS, higher pT stage, lymph node metastasis | IHC/TCGA | 68/499 | Zhang et al., 2022 [75] | |

| Worse OS, higher pT stage, clinical stage, lymph node metastasis | IHC, WB, PCR/TCGA | 59/419 | Tang et al., 2023 [20] | |

| HSP105 | Advanced clinical stage | IHC | 56 | Mohtasham et al., 2011 [61] |

| Worse survival | WB | 499 | Ono et al., 2018 [50] | |

| Worse OS | TCGA | 504 | Fan et al., 2020 [66] | |

| Worse survival, poor prognosis | IHC | 70 | Arvanitidou et al., 2020 [77] | |

| HSP110 | Worse OS | TCGA | 504 | Fan et al., 2020 [66] |

5. HSPs and Cancer Stem Cells

5.1. HSP27

5.2. HSP70

5.3. HSP90

6. HSP Inhibitors

- (1)

- HSP27 inhibitors: quercetin, RP101 (brivudine), PA11, PA50, OGX-427 (apatorsen), and ivermectin.

- (2)

- HSP70 inhibitors: apoptozole, triptolide, minnelide, artesunate, PES (pifithrin-μ), MKT-077, YM-01, and YM-08.

- (3)

- HSP90 inhibitors: geldanamycin, 17-AAG (tanespimycin), 17-DMAG (alvespimycin), IPI-504 (retaspimycin), IP-493, WK881, radicicol, NVP-AUY922 (luminespib), AT13387 (onalespib), GRP94 (glucose-regulated protein 94), STA-9090 (ganetespib), CNF-2024 (BIIB021), CUDC-305 (Debio 0932), PU-H71 (zelavespib), XL888, NVP-BEP80, sansalvamide, novobiocin, TAS-116 (pimitespib), HS-196, SNX-5422, Ku363, Ku711, and Ku757.

6.1. HSP27 Inhibitors

- (1)

- (2)

- Peptide aptamers—PA11 and PA50.

- (3)

- Antisense oligonucleotides—such as OGX-427 (apatorsen)—which interact directly with HSP27 have been investigated.

- (a)

- The inhibition of cell invasion, migration, and colony formation by suppressing MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity [112].

- (b)

- The inhibition of the progression of OSCC by the activation of the miR- 1254/CD36 pathway [113].

- (c)

- The inhibition of glycolysis and cell proliferation of OSCC cells by suppressing the G3BP1/YWHAZ 919 axis [110].

- (d)

- Ferroptosis (programmed cell death characterized by iron dependency] may also be a mechanism [114].

- (e)

- The provision of an unfavorable microenvironment for HPV+ HNSCC by increasing reactive oxygen species production, decreasing tumor pH, and inhibiting tumor growth [115].

6.2. HSP70 Inhibitors

6.3. HSP90 Inhibitors

7. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alberti, G.; Vergilio, G.; Paladino, L.; Barone, R.; Cappello, F.; Conway de Macario, E.; Macario, A.J.L.; Bucchieri, F.; Rappa, F. The Chaperone System in Breast Cancer: Roles and Therapeutic Prospects of the Molecular Chaperones Hsp27, Hsp60, Hsp70, and Hsp90. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Xiao, H.; Cao, L. Recent Advances in Heat Shock Proteins in Cancer Diagnosis, Prognosis, Metabolism and Treatment. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 142, 112074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Liu, T.; Rios, Z.; Mei, Q.; Lin, X.; Cao, S. Heat Shock Proteins and Cancer. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 38, 226–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Yang, J.; Qi, Z.; Wu, H.; Wang, B.; Zou, F.; Mei, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, W.; Liu, Q. Heat Shock Proteins: Biological Functions, Pathological Roles, and Therapeutic Opportunities. MedComm 2022, 3, e161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul, N.S.; Ahmad Alrashed, N.; Alsubaie, S.; Albluwi, H.; Badr Alsaleh, H.; Alageel, N.; Ghaleb Salma, R. Role of Extracellular Heat Shock Protein 90 Alpha in the Metastasis of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e38514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Burns, T.F. Targeting Heat Shock Proteins in Cancer: A Promising Therapeutic Approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailova, E.; Sokolenko, A.; Combs, S.E.; Shevtsov, M. Modulation of Heat Shock Proteins Levels in Health and Disease: An Integrated Perspective in Diagnostics and Therapy. Cells 2025, 14, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, W.-F.; Pang, Q.; Zhu, X.; Yang, Q.-Q.; Zhao, Q.; He, G.; Han, B.; Huang, W. Heat Shock Proteins as Hallmarks of Cancer: Insights from Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Strategies. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 17, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartl, F.U.; Bracher, A.; Hayer-Hartl, M. Molecular Chaperones in Protein Folding and Proteostasis. Nature 2011, 475, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jee, H. Size Dependent Classification of Heat Shock Proteins: A Mini-Review. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2016, 12, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Fan, X.; Yu, W. Functional Diversity of Mammalian Small Heat Shock Proteins: A Review. Cells 2023, 12, 1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraishi, N.; Onda, T.; Hayashi, K.; Onidani, K.; Watanabe, K.; Sekikawa, S.; Shibahara, T. Heat Shock Protein 90 as a Molecular Target for Therapy in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Inhibitory Effects of 17-DMAG and Ganetespib on Tumor Cells. Oncol. Rep. 2021, 45, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.K.; Shin, Y.; Han, S.; Ha, J.; Tiwari, P.K.; Kim, S.S.; Kang, I. Molecular Chaperonin HSP60: Current Understanding and Future Prospects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lianos, G.D.; Alexiou, G.A.; Mangano, A.; Mangano, A.; Rausei, S.; Boni, L.; Dionigi, G.; Roukos, D.H. The Role of Heat Shock Proteins in Cancer. Cancer Lett. 2015, 360, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrose, A.J.; Chapman, E. Function, Therapeutic Potential, and Inhibition of Hsp70 Chaperones. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 7060–7082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramaratne, A.C.; Liao, J.-Y.; Doyle, S.M.; Hoskins, J.R.; Puller, G.; Scott, M.L.; Alao, J.P.; Obaseki, I.; Dinan, J.C.; Maity, T.K.; et al. J-Domain Proteins Form Binary Complexes with Hsp90 and Ternary Complexes with Hsp90 and Hsp70. J. Mol. Biol. 2023, 435, 168184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, Y.; Chen, X.; Niu, T.; Chatterjee, A.; He, P.; Hou, G. Heat Shock Protein 90: Biological Functions, Diseases, and Therapeutic Targets. MedComm 2024, 5, e470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawrzynow, B.; Zylicz, A.; Zylicz, M. Chaperoning the Guardian of the Genome. The Two-Faced Role of Molecular Chaperones in P53 Tumor Suppressor Action. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2018, 1869, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Li, T.; Zhang, W.; Yang, X. Targeting Heat-Shock Protein 90 in Cancer: An Update on Combination Therapy. Cells 2022, 11, 2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Li, Y.; Pan, M.; Wang, Z.; Lu, T.; Liu, C.; Zhou, X.; Hu, G. HSP90AA1 Promotes Lymphatic Metastasis of Hypopharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma by Regulating Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Oncol. Res. 2023, 31, 787–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, B.J.; Guerrero-Giménez, M.E.; Prince, T.L.; Ackerman, A.; Bonorino, C.; Calderwood, S.K. Heat Shock Proteins Are Essential Components in Transformation and Tumor Progression: Cancer Cell Intrinsic Pathways and Beyond. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhendawy, H.A. Clinical Implications of Heat Shock Protein 70 in Oral Carcinogenesis and Prediction of Progression and Recurrence in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Patients: A Retrospective Clinicopathological Study. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2023, 28, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muschter, D.; Geyer, F.; Bauer, R.; Ettl, T.; Schreml, S.; Haubner, F. A Comparison of Cell Survival and Heat Shock Protein Expression after Radiation in Normal Dermal Fibroblasts, Microvascular Endothelial Cells, and Different Head and Neck Squamous Carcinoma Cell Lines. Clin. Oral Investig. 2018, 22, 2251–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somu, P.; Mohanty, S.; Basavegowda, N.; Yadav, A.K.; Paul, S.; Baek, K.-H. The Interplay between Heat Shock Proteins and Cancer Pathogenesis: A Novel Strategy for Cancer Therapeutics. Cancers 2024, 16, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konda, J.D.; Olivero, M.; Musiani, D.; Lamba, S.; Di Renzo, M.F. Heat-Shock Protein 27 (HSP27, HSPB1) Is Synthetic Lethal to Cells with Oncogenic Activation of MET, EGFR and BRAF. Mol. Oncol. 2017, 11, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Liu, T.-T.; Wang, H.-H.; Hong, H.-M.; Yu, A.L.; Feng, H.-P.; Chang, W.-W. Hsp27 Participates in the Maintenance of Breast Cancer Stem Cells through Regulation of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Nuclear Factor-κB. Breast Cancer Res. 2011, 13, R101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, K.; Chawla, G.; Puri, A.; Krishnan, M.; Aneja, T.; Gill, K. Heat Shock Protein 27 (HSP27) as a Potential Prognostic Marker: Immunohistochemical Analysis of Oral Epithelial Dysplasia and Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cureus 2022, 14, e33020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgharzadeh, F.; Moradi-Marjaneh, R.; Marjaneh, M.M. The Role of Heat Shock Protein 27 in Carcinogenesis and Treatment of Colorectal Cancer. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2022, 28, 2677–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampros, M.; Vlachos, N.; Voulgaris, S.; Alexiou, G.A. The Role of Hsp27 in Chemotherapy Resistance. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiota, M.; Bishop, J.L.; Nip, K.M.; Zardan, A.; Takeuchi, A.; Cordonnier, T.; Beraldi, E.; Bazov, J.; Fazli, L.; Chi, K.; et al. Hsp27 Regulates Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition, Metastasis, and Circulating Tumor Cells in Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 3109–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Wang, Y.; Gan, M.; Duan, Q. Prognosis and Predictive Value of Heat-Shock Proteins Expression in Oral Cancer: A PRISMA-Compliant Meta-Analysis. Medicine 2021, 100, e24274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Xu, X.; Yu, Y.; Graham, M.; Prince, M.E.; Carey, T.E.; Sun, D. Silencing Heat Shock Protein 27 Decreases Metastatic Behavior of Human Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancer Cells In Vitro. Mol. Pharm. 2010, 7, 1283–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Z.; Liang, W.; Luo, L. HSP27 Promotes Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition through Activation of the β-Catenin/MMP3 Pathway in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Cells. Transl. Cancer Res. 2019, 8, 1268–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karri, R.L.; Subramanyam, R.V.; Venigella, A.; Babburi, S.; Pinisetti, S.; Rudraraju, A. Differential Expression of Heat Shock Protein 27 in Oral Epithelial Dysplasias and Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Microsc. Ultrastruct. 2020, 8, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; Liang, Y.; Li, L.; Tan, Y.; Liu, Q.; Liu, T.; Lu, X. Revisiting the Old Data of Heat Shock Protein 27 Expression in Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Enigmatic HSP27, More Than Heat Shock. Cells 2022, 11, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vostakolaei, M.A.; Hatami-Baroogh, L.; Babaei, G.; Molavi, O.; Kordi, S.; Abdolalizadeh, J. Hsp70 in Cancer: A Double Agent in the Battle between Survival and Death. J. Cell Physiol. 2021, 236, 3420–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, J.K.; Xiong, X.; Ren, X.; Yang, J.-M.; Song, J. Heat Shock Proteins in Cancer Immunotherapy. J. Oncol. 2019, 2019, 3267207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karri, R.L.; Subramanyam, R.V.; Venigella, A.; Babburi, S.; Pinisetti, S.; Amrutha, R.; Nelakurthi, H. Expression of Heat Shock Protein 70 in Oral Epithelial Dysplasia and Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2023, 19, 1939–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albakova, Z.; Armeev, G.A.; Kanevskiy, L.M.; Kovalenko, E.I.; Sapozhnikov, A.M. HSP70 Multi-Functionality in Cancer. Cells 2020, 9, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanka, K.P.; Majumdar, S.; Kotina, S.; Uppala, D.; Balla, H. Expression of Heat Shock Protein 70 in Oral Epithelial Dysplasia and Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: An Immunohistochemical Study. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2019, 10, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasioumi, P.; Vrazeli, P.; Vezyraki, P.; Zerikiotis, S.; Katsouras, C.; Damalas, A.; Angelidis, C. Hsp70 (HSP70A1A) Downregulation Enhances the Metastatic Ability of Cancer Cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2019, 54, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perconti, G.; Maranto, C.; Romancino, D.P.; Rubino, P.; Feo, S.; Bongiovanni, A.; Giallongo, A. Pro-Invasive Stimuli and the Interacting Protein Hsp70 Favour the Route of Alpha-Enolase to the Cell Surface. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabakov, A.E.; Yakimova, A.O. Hypoxia-Induced Cancer Cell Responses Driving Radioresistance of Hypoxic Tumors: Approaches to Targeting and Radiosensitizing. Cancers 2021, 13, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.L.; Chung, T.-W.; Kim, S.; Hwang, B.; Kim, J.M.; Lee, H.M.; Cha, H.-J.; Seo, Y.; Choe, S.Y.; Ha, K.-T.; et al. HSP70-1 Is Required for Interleukin-5-Induced Angiogenic Responses through eNOS Pathway. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-K.; Na, H.J.; Lee, W.R.; Jeoung, M.H.; Lee, S. Heat Shock Protein 70-1A Is a Novel Angiogenic Regulator. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 469, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.; Kim, M.R.; Kim, T.-K.; Lee, W.R.; Kim, J.H.; Heo, K.; Lee, S. CLEC14a-HSP70-1A Interaction Regulates HSP70-1A-Induced Angiogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freilich, R.; Arhar, T.; Abrams, J.L.; Gestwicki, J.E. Protein-Protein Interactions in the Molecular Chaperone Network. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 940–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumi, M.P.; Ghosh, A. Hsp90 in Human Diseases: Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Approaches. Cells 2022, 11, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, K.; Wei, S.; Sugarman, E.T.; Liu, L.; Zhang, G. Targeting HSP90 as a Novel Therapy for Cancer: Mechanistic Insights and Translational Relevance. Cells 2022, 11, 2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ono, K.; Eguchi, T.; Sogawa, C.; Calderwood, S.K.; Futagawa, J.; Kasai, T.; Seno, M.; Okamoto, K.; Sasaki, A.; Kozaki, K.-I. HSP-Enriched Properties of Extracellular Vesicles Involve Survival of Metastatic Oral Cancer Cells. J. Cell Biochem. 2018, 119, 7350–7362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basset, C.A.; Rappa, F.; Barone, R.; Florena, A.M.; Porcasi, R.; Conway de Macario, E.; Macario, A.J.L.; Leone, A. The Chaperone System in Salivary Glands: Hsp90 Prospects for Differential Diagnosis and Treatment of Malignant Tumors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, H.J.; Zhang, H. Targeting Oxidative Stress in Disease: Promise and Limitations of Antioxidant Therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 689–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Tang, C.; Yang, F.; Ekpenyong, A.; Qin, R.; Xie, J.; Momen-Heravi, F.; Saba, N.F.; Teng, Y. HSP90 Inhibition Suppresses Tumor Glycolytic Flux to Potentiate the Therapeutic Efficacy of Radiotherapy for Head and Neck Cancer. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, T.E.M.M.; Raghavendra, N.M.; Penido, C. Natural Heat Shock Protein 90 Inhibitors in Cancer and Inflammation. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 189, 112063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mese, H.; Sasaki, A.; Nakayama, S.; Yoshioka, N.; Yoshihama, Y.; Kishimoto, K.; Matsumura, T. Prognostic Significance of Heat Shock Protein 27 (HSP27) in Patients with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2002, 9, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzio, L.L.; Leonardi, R.; Mariggiò, M.A.; Mignogna, M.D.; Rubini, C.; Vinella, A.; Pannone, G.; Giannetti, L.; Serpico, R.; Testa, N.F.; et al. HSP 27 as Possible Prognostic Factor in Patients with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Histol. Histopathol. 2004, 19, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzio, L.L.; Campisi, G.; Farina, A.; Rubini, C.; Ferrari, F.; Falaschini, S.; Leonardi, R.; Carinci, F.; Stalbano, S.; De Rosa, G. Prognostic Value of HSP27 in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Retrospective Analysis of 57 Tumours. Anticancer Res. 2006, 26, 1343–1349. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Liu, X.; Sheng, S.; Ye, H.; Peng, T.; Shi, F.; Crowe, D.L.; Zhou, X. Dysregulation of Heat Shock Protein 27 Expression in Oral Tongue Squamous Cell Carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2009, 9, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowczak, J.; Łaszczych, D.; Czyżnikiewicz, A.; Marszałek, A.; Szylberg, Ł.; Bodnar, M. Low Expression of HSP27 and HSP70 Predicts Poor Prognosis in Laryngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 151, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandour-Edwards, R.; Trock, B.J.; Gumerlock, P.; Donald, P.J. Heat Shock Protein and P53 Expression in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1998, 118, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohtasham, N.; Babakoohi, S.; Montaser-Kouhsari, L.; Memar, B.; Salehinejad, J.; Rahpeyma, A.; Khageh-Ahmady, S.; Marouzi, P.; Firooz, A.; Pazoki-Toroudi, H.; et al. The Expression of Heat Shock Proteins 27 and 105 in Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Tongue and Relationship with Clinicopathological Index. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2011, 16, e730–e735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajalyakeen, H.; Almohareb, M.; Al-Assaf, M. Overexpression of Heat Shock Protein 27 (HSP-27) Is Associated with Bad Prognosis in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Dent. Med. Probl. 2020, 57, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karam, J.; Fadous-Khalifé, M.C.; Tannous, R.; Fakhreddine, S.; Massoud, M.; Hadchity, J.; Aftimos, G.; Hadchity, E. Role of Krüppel-like Factor 4 and Heat Shock Protein 27 in Cancer of the Larynx. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 7, 808–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaigorodova, E.V.; Zavyalova, M.V.; Bychkov, V.A.; Perelmuter, V.M.; Choynzonov, E.L. Functional State of the Hsp27 Chaperone as a Molecular Marker of an Unfavorable Course of Larynx Cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2016, 17, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Liao, Z.; Zhou, C.; Lin, R.; Lu, J.; Cai, L.; Tan, X.; Zeng, W.; Lu, X.; Zheng, W.; et al. HSP47 Is Associated with the Prognosis of Laryngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma by Inhibiting Cell Viability and Invasion and Promoting Apoptosis. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 38, 2444–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Fan, G.; Tu, Y.; Wu, N.; Xiao, H. The Expression Profiles and Prognostic Values of HSPs Family Members in Head and Neck Cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2020, 20, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, B.C.; Dourado, M.R.; de Moraes, E.F.; Panini, L.M.; Elseragy, A.; Téo, F.H.; Guimarães, G.N.; Machado, R.A.; Risteli, M.; Gurgel Rocha, C.A.; et al. Overexpression of Heat-Shock Protein 47 Impacts Survival of Patients with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2023, 52, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Tang, Y.; Luo, J.; Yang, Y.; Zang, H.; Ma, J.; Fan, S.; Wen, Q. High Expression of HSP60 and Survivin Predicts Poor Prognosis for Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Patients. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Srivastava, A.; Ralhan, R. Expression of 70-kDa Heat Shock Protein in Oral Lesions: Marker of Biological Stress or Pathogenicity. Oral Oncol. 1998, 34, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-S.; Tsai, C.-H.; Ho, Y.-C.; Chang, Y.-C. The Upregulation of Heat Shock Protein 70 Expression in Areca Quid Chewing-Associated Oral Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Oral Oncol. 2008, 44, 884–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.G.; Kim, J.-S.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, K.H.; Sung, M.-W.; Choe, J.-Y.; Kim, J.E.; Jung, Y.H. Expression of Hypoxic Signaling Markers in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Its Clinical Significance. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015, 272, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceylan, O.; Arslan, R. The Importance of Heat Shock-Related 70-kDa Protein 2 Expression in Laryngeal Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Eurasian J. Med. 2022, 54, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar, J.K.; Cierpikowski, P.; Lis-Nawara, A.; Duc, P.; Hałoń, A.; Radwan-Oczko, M. Comparison of P53, HSP90, E-Cadherin and HPV in Oral Lichen Planus and Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2021, 41, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, W.-C.; Tsai, P.-T.; Lin, C.-K.; Shieh, Y.-S.; Chen, Y.-W. Expression Pattern of Heat Shock Protein 90 in Patients with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Northern Taiwan. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 55, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yin, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, M.; Xu, W.; Wei, Z.; Song, C.; Han, S.; Han, W. HSP90AB1 Promotes the Proliferation, Migration, and Glycolysis of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2022, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.M.; Fraga, C.A.d.C.; Xavier, A.R.E.d.O.; Xavier, M.A.d.S.; Souza, M.G.; Jesus, S.F.d.; Paula, A.M.B.d.; Farias, L.C.; Santos, S.H.S.; Santos, T.G.; et al. Prion Protein Is Associated with a Worse Prognosis of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2021, 50, 985–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitidou, S.; Martinelli-Kläy, C.P.; Samson, J.; Lobrinus, J.A.; Dulguerov, N.; Lombardi, T. HSP105 Expression in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Correlation with Clinicopathological Features and Outcomes. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2020, 49, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Ralhan, R. Differential Expression of 70-kDa Heat Shock-Protein in Human Oral Tumorigenesis. Int. J. Cancer 1995, 63, 774–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavi, N.; Mohsenifar, Z.; Baghban, A.A.; Arjomandkhah, A. CD20+ Tumor Infiltrating B Lymphocyte in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Correlation with Clinicopathologic Characteristics and Heat Shock Protein 70 Expression. Pathol. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 4810751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, D.C.; Ravindran, S.; Shyamsundar, V.; Sankarapandian, S.; Krishnamurthy, A.; Sivagnanam, A.; Madhavan, Y.; Ramshankar, V. Integrated Proteomics Based on 2D Gel Electrophoresis and Mass Spectrometry with Validations: Identification of a Biomarker Compendium for Oral Submucous Fibrosis-An Indian Study. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumoto, C.; Uchida, D.; Kawamata, H. Diversity of the Origin of Cancer Stem Cells in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Its Clinical Implications. Cancers 2022, 14, 3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabakov, A.; Yakimova, A.; Matchuk, O. Molecular Chaperones in Cancer Stem Cells: Determinants of Stemness and Potential Targets for Antitumor Therapy. Cells 2020, 9, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zisis, V.; Venou, M.; Poulopoulos, A.; Andreadis, D. Cancer Stem Cells in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Treatment Modalities. Balk. J. Dent. Med. 2021, 25, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, T.; Nakashiro, K.-I.; Fukumoto, C.; Hyodo, T.; Sawatani, Y.; Shimura, M.; Kamimura, R.; Kuribayashi, N.; Fujita, A.; Uchida, D.; et al. Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma May Originate from Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cells. Oncol. Lett. 2021, 21, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lettini, G.; Lepore, S.; Crispo, F.; Sisinni, L.; Esposito, F.; Landriscina, M. Heat Shock Proteins in Cancer Stem Cell Maintenance: A Potential Therapeutic Target? Histol. Histopathol. 2020, 35, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-K.; Kam, H.; Kim, K.-Y.; Park, S.I.; Lee, Y.-S. Targeting Heat Shock Protein 27 in Cancer: A Druggable Target for Cancer Treatment? Cancers 2019, 11, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, G.; Zhou, C.; Wang, P.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, S.; Huang, S.; Su, W.; Jiang, P.; et al. Inactivation of P38 MAPK Contributes to Stem Cell-like Properties of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 26702–26717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-P.; Lee, Y.-T.; Wang, J.-Y.; Miller, S.A.; Chiou, S.-H.; Hung, M.-C.; Hung, S.-C. Survival of Cancer Stem Cells under Hypoxia and Serum Depletion via Decrease in PP2A Activity and Activation of P38-MAPKAPK2-Hsp27. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-H.; Wu, Y.-T.; Hsieh, H.-C.; Yu, Y.; Yu, A.L.; Chang, W.-W. Epidermal Growth Factor/Heat Shock Protein 27 Pathway Regulates Vasculogenic Mimicry Activity of Breast Cancer Stem/Progenitor Cells. Biochimie 2014, 104, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-F.; Nieh, S.; Jao, S.-W.; Liu, C.-L.; Wu, C.-H.; Chang, Y.-C.; Yang, C.-Y.; Lin, Y.-S. Quercetin Suppresses Drug-Resistant Spheres via the P38 MAPK-Hsp27 Apoptotic Pathway in Oral Cancer Cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Shin, H.-S.; Choi, G.; Lee, Y.C. Proteomic Analysis of CD44(+) and CD44(-) Gastric Cancer Cells. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2014, 396, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, C.; Lager, T.W.; Guldner, I.H.; Wu, M.-Z.; Hishida, Y.; Hishida, T.; Ruiz, S.; Yamasaki, A.E.; Gilson, R.C.; Belmonte, J.C.I.; et al. Cell Surface GRP78 Promotes Stemness in Normal and Neoplastic Cells. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronci, M.; Catanzaro, G.; Pieroni, L.; Po, A.; Besharat, Z.M.; Greco, V.; Levi Mortera, S.; Screpanti, I.; Ferretti, E.; Urbani, A. Proteomic Analysis of Human Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) Medulloblastoma Stem-like Cells. Mol. Biosyst. 2015, 11, 1603–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, N.; Jagadish, N.; Surolia, A.; Suri, A. Heat Shock Protein 70-2 (HSP70-2) a Novel Cancer Testis Antigen That Promotes Growth of Ovarian Cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2017, 7, 1252–1269, Erratum in Am. J. Cancer Res. 2020, 10, 1919–1920. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, B.; Cao, J.; Tian, J.-H.; Yu, C.-Y.; Huang, Q.; Yu, J.-J.; Ma, R.; Wang, J.; Xu, F.; Wang, L.-B. Mortalin Maintains Breast Cancer Stem Cells Stemness via Activation of Wnt/GSK3β/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2021, 11, 2696–2716. [Google Scholar]

- Kabakov, A.E.; Gabai, V.L. HSP70s in Breast Cancer: Promoters of Tumorigenesis and Potential Targets/Tools for Therapy. Cells 2021, 10, 3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.Y.; Le, H.T.; Min, H.-Y.; Pei, H.; Lim, Y.; Song, I.; Nguyen, Y.T.K.; Hong, S.; Han, B.W.; Lee, H.-Y. Evodiamine Inhibits Both Stem Cell and Non-Stem-Cell Populations in Human Cancer Cells by Targeting Heat Shock Protein 70. Theranostics 2021, 11, 2932–2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-H.; Weng, J.-R.; Lin, H.-W.; Lu, M.-T.; Liu, Y.-C.; Chu, P.-C. Targeting Triple Negative Breast Cancer Stem Cells by Heat Shock Protein 70 Inhibitors. Cancers 2022, 14, 4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prager, B.C.; Xie, Q.; Bao, S.; Rich, J.N. Cancer Stem Cells: The Architects of the Tumor Ecosystem. Cell Stem Cell 2019, 24, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, M.K.; Celià-Terrassa, T. Dynamics of Phenotypic Heterogeneity Associated with EMT and Stemness during Cancer Progression. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cierpikowski, P.; Lis-Nawara, A.; Bar, J. Prognostic Value of WNT1, NOTCH1, PDGFRβ, and CXCR4 in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2023, 43, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cierpikowski, P.; Lis-Nawara, A.; Bar, J. SHH Expression Is Significantly Associated With Cancer Stem Cell Markers in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2021, 41, 5405–5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, C.; Kovatch, K.J.; Sim, M.W.; Wang, G.; Prince, M.E.; Carey, T.E.; Davis, R.; Blagg, B.S.J.; Cohen, M.S. Novel C-Terminal Heat Shock Protein 90 Inhibitors (KU711 and Ku757) Are Effective in Targeting Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cancer Stem Cells. Neoplasia 2017, 19, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, T.-M.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, Y.-J.; Sung, D.; Oh, E.; Jang, S.; Farrand, L.; Hoang, V.-H.; Nguyen, C.-T.; Ann, J.; et al. C-Terminal HSP90 Inhibitor L80 Elicits Anti-Metastatic Effects in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer via STAT3 Inhibition. Cancer Lett. 2019, 447, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinrich, J.C.; Donakonda, S.; Haupt, V.J.; Lennig, P.; Zhang, Y.; Schroeder, M. New HSP27 Inhibitors Efficiently Suppress Drug Resistance Development in Cancer Cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 68156–68169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastogi, S.; Joshi, A.; Sato, N.; Lee, S.; Lee, M.-J.; Trepel, J.B.; Neckers, L. An Update on the Status of HSP90 Inhibitors in Cancer Clinical Trials. Cell Stress Chaperones 2024, 29, 519–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Tang, C.; Li, L.; Li, R.; Fan, Y. Quercetin Blocks T-AUCB-Induced Autophagy by Hsp27 and Atg7 Inhibition in Glioblastoma Cells In Vitro. J. Neurooncol. 2016, 129, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Dong, X.-S.; Gao, H.-Y.; Jiang, Y.-F.; Jin, Y.-L.; Chang, Y.-Y.; Chen, L.-Y.; Wang, J.-H. Suppression of HSP27 Increases the Anti-Tumor Effects of Quercetin in Human Leukemia U937 Cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elattar, T.M.; Virji, A.S. The Inhibitory Effect of Curcumin, Genistein, Quercetin and Cisplatin on the Growth of Oral Cancer Cells In Vitro. Anticancer Res. 2000, 20, 1733–1738. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.-F.; Liu, S.-H.; Ho, T.-J.; Lee, K.-I.; Fang, K.-M.; Lo, W.-C.; Liu, J.-M.; Wu, C.-C.; Su, C.-C. Quercetin Induces Tongue Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cell Apoptosis via the JNK Activation-Regulated ERK/GSK-3α/β-Mediated Mitochondria-Dependent Apoptotic Signaling Pathway. Oncol. Lett. 2022, 23, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, H.-K.; Kim, D. Quercetin Induces Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in YD10B and YD38 Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2023, 24, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.-Y.; Lien, C.-H.; Lee, M.-F.; Huang, C.-Y. Quercetin Suppresses Cellular Migration and Invasion in Human Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC). Biomedicine 2016, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xia, J.-S.; Wu, J.-H.; Chen, Y.-G.; Qiu, C.-J. Quercetin Suppresses Cell Survival and Invasion in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma via the miR-1254/CD36 Cascade In Vitro. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2021, 40, 1413–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.-W.; Liu, C.-L.; Li, X.-M.; Shang, Y. Quercetin Induces Ferroptosis by Inactivating mTOR/S6KP70 Pathway in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2024, 34, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Y.; Coppock, J.D.; Haugrud, A.B.; Lee, J.H.; Messerli, S.M.; Miskimins, W.K. Dichloroacetate and Quercetin Prevent Cell Proliferation, Induce Cell Death and Slow Tumor Growth in a Mouse Model of HPV-Positive Head and Neck Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C.-Y.; Hong, S.-C.; Chang, C.-M.; Chen, Y.-H.; Liao, P.-C.; Huang, C.-Y. Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells with Acquired Resistance to Erlotinib Are Sensitive to Anti-Cancer Effect of Quercetin via Pyruvate Kinase M2 (PKM2). Cells 2023, 12, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, S.; Ru, Y.; Li, J.; Guo, P.; Jiao, W.; Miao, J.; Sun, L.; Chen, M.; et al. Light-Activated Photosensitizer/Quercetin Co-Loaded Extracellular Vesicles for Precise Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 671, 125224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, J.-C.; Tuukkanen, A.; Schroeder, M.; Fahrig, T.; Fahrig, R. RP101 (Brivudine) Binds to Heat Shock Protein HSP27 (HSPB1) and Enhances Survival in Animals and Pancreatic Cancer Patients. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 137, 1349–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, J.R.; McAlpine, S.R. Heat Shock Proteins 27, 40, and 70 as Combinational and Dual Therapeutic Cancer Targets. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 1923–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibert, B.; Hadchity, E.; Czekalla, A.; Aloy, M.-T.; Colas, P.; Rodriguez-Lafrasse, C.; Arrigo, A.-P.; Diaz-Latoud, C. Inhibition of Heat Shock Protein 27 (HspB1) Tumorigenic Functions by Peptide Aptamers. Oncogene 2011, 30, 3672–3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, A.H.; Murphy, P.B.; Peyton, J.D.; Shipley, D.L.; Al-Hazzouri, A.; Rodriguez, F.A.; Womack, M.S.; Xiong, H.Q.; Waterhouse, D.M.; Tempero, M.A.; et al. A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Phase II Trial of Gemcitabine and Nab-Paclitaxel Plus Apatorsen or Placebo in Patients with Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer: The RAINIER Trial. Oncologist 2017, 22, 1427–e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, J.E.; Hahn, N.M.; Regan, M.M.; Werner, L.; Alva, A.; George, S.; Picus, J.; Alter, R.; Balar, A.; Hoffman-Censits, J.; et al. Apatorsen plus Docetaxel versus Docetaxel Alone in Platinum-Resistant Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma (Borealis-2). Br. J. Cancer 2018, 118, 1434–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lelj-Garolla, B.; Kumano, M.; Beraldi, E.; Nappi, L.; Rocchi, P.; Ionescu, D.N.; Fazli, L.; Zoubeidi, A.; Gleave, M.E. Hsp27 Inhibition with OGX-427 Sensitizes Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells to Erlotinib and Chemotherapy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2015, 14, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Shen, J.; Guo, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, J. Bortezomib Promotes Apoptosis of Multiple Myeloma Cells by Regulating HSP27. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 20, 2410–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadchity, E.; Aloy, M.-T.; Paulin, C.; Armandy, E.; Watkin, E.; Rousson, R.; Gleave, M.; Chapet, O.; Rodriguez-Lafrasse, C. Heat Shock Protein 27 as a New Therapeutic Target for Radiation Sensitization of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Mol. Ther. 2009, 17, 1387–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nappi, L.; Aguda, A.H.; Nakouzi, N.A.; Lelj-Garolla, B.; Beraldi, E.; Lallous, N.; Thi, M.; Moore, S.; Fazli, L.; Battsogt, D.; et al. Ivermectin Inhibits HSP27 and Potentiates Efficacy of Oncogene Targeting in Tumor Models. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Lu, M.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Wei, X.; Si, J.; Han, J.; Yao, X.; Zhang, J.; et al. Ivermectin Induces Apoptosis of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma via Mitochondrial Pathway. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Bi, S.; Wei, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, C.; Xie, S. Ivermectin Suppresses Tumour Growth and Metastasis through Degradation of PAK1 in Oesophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 5387–5401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, K.N.; Yu, E.Y.; Jacobs, C.; Bazov, J.; Kollmannsberger, C.; Higano, C.S.; Mukherjee, S.D.; Gleave, M.E.; Stewart, P.S.; Hotte, S.J. A Phase I Dose-Escalation Study of Apatorsen (OGX-427), an Antisense Inhibitor Targeting Heat Shock Protein 27 (Hsp27), in Patients with Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer and Other Advanced Cancers. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 1116–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, L.; Bolaender, A.; Patel, H.J.; Taldone, T. Heat Shock Protein (HSP) Drug Discovery and Development: Targeting Heat Shock Proteins in Disease. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2016, 16, 2753–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Zhou, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, G. HSP70 Family in Cancer: Signaling Mechanisms and Therapeutic Advances. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.-X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, S.-S.; Wu, J.; Su, T.; Wang, W.-M. Heat Shock Proteins 70 Regulate Cell Motility and Invadopodia-Associated Proteins Expression in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 890218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-H.; Baek, K.-H.; Shin, I.; Shin, I. Subcellular Hsp70 Inhibitors Promote Cancer Cell Death via Different Mechanisms. Cell Chem. Biol. 2018, 25, 1242–1254.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-Y.; Lin, C.-K.; Hsieh, C.-C.; Tsao, C.-H.; Lin, C.-S.; Peng, B.; Chen, Y.-T.; Ting, C.-C.; Chang, W.-C.; Lin, G.-J.; et al. Anti-Oral Cancer Effects of Triptolide by Downregulation of DcR3 In Vitro, In Vivo, and in Preclinical Patient-Derived Tumor Xenograft Model. Head Neck 2019, 41, 1260–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zhang, B.; Lv, W.; Lai, C.; Chen, Z.; Wang, R.; Long, X.; Feng, X. Triptolide Inhibits Cell Growth and GRP78 Protein Expression but Induces Cell Apoptosis in Original and Radioresistant NPC Cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 49588–49596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, C.-S.; Yang, C.-Y.; Lin, C.-K.; Lin, G.-J.; Sytwu, H.-K.; Chen, Y.-W. Triptolide Suppresses Oral Cancer Cell PD-L1 Expression in the Interferon-γ-Modulated Microenvironment In Vitro, In Vivo, and in Clinical Patients. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 133, 111057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A.; Beyer, G.; Chugh, R.; Skube, S.J.; Majumder, K.; Banerjee, S.; Sangwan, V.; Li, L.; Dawra, R.; Subramanian, S.; et al. Triptolide Abrogates Growth of Colon Cancer and Induces Cell Cycle Arrest by Inhibiting Transcriptional Activation of E2F. Lab. Investig. 2015, 95, 648–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, B.A.; Chen, E.Z.; Tang, S.; Belgum, H.S.; McCauley, J.A.; Evenson, K.A.; Etchison, R.G.; Jay-Dixon, J.; Patel, M.R.; Raza, A.; et al. Triptolide and Its Prodrug Minnelide Suppress Hsp70 and Inhibit In Vivo Growth in a Xenograft Model of Mesothelioma. Genes Cancer 2015, 6, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caicedo-Granados, E.; Lin, R.; Clements-Green, C.; Yueh, B.; Sangwan, V.; Saluja, A. Wild-Type P53 Reactivation by Small-Molecule MinnelideTM in Human Papillomavirus (HPV)-Positive Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2014, 50, 1149–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, J.-L.; Kim, E.H.; Jang, H.; Shin, D. Nrf2 Inhibition Reverses the Resistance of Cisplatin-Resistant Head and Neck Cancer Cells to Artesunate-Induced Ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2017, 11, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, H.; Yoshikawa, K.; Shimada, A.; Sano, R.; Inukai, D.; Yamanaka, S.; Suzuki, S.; Ueda, R.; Ueda, H.; Fujimoto, Y.; et al. Artesunate and Cisplatin Synergistically Inhibit HNSCC Cell Growth and Promote Apoptosis with Artesunate-induced Decreases in Rb and Phosphorylated Rb Levels. Oncol. Rep. 2023, 50, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousaki, A.; Miyata, Y.; Jinwal, U.K.; Dickey, C.A.; Gestwicki, J.E.; Zuiderweg, E.R.P. Allosteric Drugs: The Interaction of Antitumor Compound MKT-077 with Human Hsp70 Chaperones. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 411, 614–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyata, Y.; Li, X.; Lee, H.-F.; Jinwal, U.K.; Srinivasan, S.R.; Seguin, S.P.; Young, Z.T.; Brodsky, J.L.; Dickey, C.A.; Sun, D.; et al. Synthesis and Initial Evaluation of YM-08, a Blood-Brain Barrier Permeable Derivative of the Heat Shock Protein 70 (Hsp70) Inhibitor MKT-077, Which Reduces Tau Levels. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2013, 4, 930–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Liu, J.; Guo, S.-Y.; Liu, H.-L.; Li, S.-Z. HSP70 Inhibitor Combined with Cisplatin Suppresses the Cervical Cancer Proliferation In Vitro and Transplanted Tumor Growth: An Experimental Study. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2017, 10, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skorupan, N.; Ahmad, M.I.; Steinberg, S.M.; Trepel, J.B.; Cridebring, D.; Han, H.; Von Hoff, D.D.; Alewine, C. A Phase II Trial of the Super-Enhancer Inhibitor MinnelideTM in Advanced Refractory Adenosquamous Carcinoma of the Pancreas. Future Oncol. 2022, 18, 2475–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeon, A.M.; Egan, A.; Chandanshive, J.; McMahon, H.; Griffith, D.M. Novel Improved Synthesis of HSP70 Inhibitor, Pifithrin-μ. In Vitro Synergy Quantification of Pifithrin-μ Combined with Pt Drugs in Prostate and Colorectal Cancer Cells. Molecules 2016, 21, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.H.; Saluja, A.; Vickers, S.; Hong, J.Y.; Kim, S.T.; Lavania, S.; Pandey, S.; Gupta, V.K.; Velagapudi, M.R.; Lee, J. The Safety and Efficacy Outcomes of Minnelide given Alone or in Combination with Paclitaxel in Advanced Gastric Cancer: A Phase I Trial. Cancer Lett. 2024, 597, 217041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borazanci, E.; Saluja, A.; Gockerman, J.; Velagapudi, M.; Korn, R.; Von Hoff, D.; Greeno, E. First-in-Human Phase I Study of Minnelide in Patients With Advanced Gastrointestinal Cancers: Safety, Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Antitumor Activity. Oncologist 2024, 29, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magyar, C.T.J.; Vashist, Y.K.; Stroka, D.; Kim-Fuchs, C.; Berger, M.D.; Banz, V.M. Heat Shock Protein 90 (HSP90) Inhibitors in Gastrointestinal Cancer: Where Do We Currently Stand?-A Systematic Review. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 8039–8050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basset, C.A.; Conway de Macario, E.; Leone, L.G.; Macario, A.J.L.; Leone, A. The Chaperone System in Cancer Therapies: Hsp90. J. Mol. Histol. 2023, 54, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misso, G.; Giuberti, G.; Lombardi, A.; Grimaldi, A.; Ricciardiello, F.; Giordano, A.; Tagliaferri, P.; Abbruzzese, A.; Caraglia, M. Pharmacological Inhibition of HSP90 and Ras Activity as a New Strategy in the Treatment of HNSCC. J. Cell Physiol. 2013, 228, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.M.; Mukerji, R.; Samadi, A.K.; Zhao, H.; Blagg, B.S.J.; Cohen, M.S. Novel C-Terminal Hsp90 Inhibitor for Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancer (HNSCC) with In Vivo Efficacy and Improved Toxicity Profiles Compared with Standard Agents. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 19, S483–S490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shintani, S.; Zhang, T.; Aslam, A.; Sebastian, K.; Yoshimura, T.; Hamakawa, H. P53-Dependent Radiosensitizing Effects of Hsp90 Inhibitor 17-Allylamino-17-Demethoxygeldanamycin on Human Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cell Lines. Int. J. Oncol. 2006, 29, 1111–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ui, T.; Morishima, K.; Saito, S.; Sakuma, Y.; Fujii, H.; Hosoya, Y.; Ishikawa, S.; Aburatani, H.; Fukayama, M.; Niki, T.; et al. The HSP90 Inhibitor 17-N-Allylamino-17-Demethoxy Geldanamycin (17-AAG) Synergizes with Cisplatin and Induces Apoptosis in Cisplatin-Resistant Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cell Lines via the Akt/XIAP Pathway. Oncol. Rep. 2014, 31, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexiou, G.A.; Goussia, A.; Voulgaris, S.; Fotopoulos, A.D.; Fotakopoulos, G.; Ntoulia, A.; Zikou, A.; Tsekeris, P.; Argyropoulou, M.I.; Kyritsis, A.P. Prognostic Significance of MRP5 Immunohistochemical Expression in Glioblastoma. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2012, 69, 1387–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.K.; Jeong, K.-H.; Choi, H.; Ahn, H.-J.; Lee, M.-H. Heat Shock Protein 90 Inhibitor Enhances Apoptosis by Inhibiting the AKT Pathway in Thermal-Stimulated SK-MEL-2 Human Melanoma Cell Line. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2018, 90, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Marmarelis, M.E.; Hodi, F.S. Activity of the Heat Shock Protein 90 Inhibitor Ganetespib in Melanoma. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Naz, S.; Leiker, A.J.; Choudhuri, R.; Preston, O.; Sowers, A.L.; Gohain, S.; Gamson, J.; Mathias, A.; Waes, C.V.; Cook, J.A.; et al. Pharmacological Inhibition of HSP90 Radiosensitizes Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Xenograft by Inhibition of DNA Damage Repair, Nucleotide Metabolism, and Radiation-Induced Tumor Vasculogenesis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2021, 110, 1295–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, R.K.; Pal, S.; Kondapi, K.; Sitto, M.; Dewar, C.; Devasia, T.; Schipper, M.J.; Thomas, D.G.; Basrur, V.; Pai, M.P.; et al. Low-Dose Hsp90 Inhibitor Selectively Radiosensitizes HNSCC and Pancreatic Xenografts. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 5246–5257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegelberg, D.; Dascalu, A.; Mortensen, A.C.; Abramenkovs, A.; Kuku, G.; Nestor, M.; Stenerlöw, B. The Novel HSP90 Inhibitor AT13387 Potentiates Radiation Effects in Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Adenocarcinoma Cells. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 35652–35666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, M.; Barker, H.E.; Khan, A.A.; Pedersen, M.; Dillon, M.; Mansfield, D.C.; Patel, R.; Kyula, J.N.; Bhide, S.A.; Newbold, K.L.; et al. HSP90 Inhibition Sensitizes Head and Neck Cancer to Platin-Based Chemoradiotherapy by Modulation of the DNA Damage Response Resulting in Chromosomal Fragmentation. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Zhang, H.; Lundgren, K.; Wilson, L.; Burrows, F.; Shores, C.G. BIIB021, a Novel Hsp90 Inhibitor, Sensitizes Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma to Radiotherapy. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 126, 1216–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, J.A.; Wise, S.C.; Hu, M.; Gouveia, C.; Broek, R.V.; Freudlsperger, C.; Kannabiran, V.R.; Arun, P.; Mitchell, J.B.; Chen, Z.; et al. HSP90 Inhibitor SNX5422/2112 Targets the Dysregulated Signal and Transcription Factor Network and Malignant Phenotype of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Transl. Oncol. 2013, 6, 429-IN5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mielczarek-Lewandowska, A.; Hartman, M.L.; Czyz, M. Inhibitors of HSP90 in Melanoma. Apoptosis 2020, 25, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solárová, Z.; Mojžiš, J.; Solár, P. Hsp90 Inhibitor as a Sensitizer of Cancer Cells to Different Therapies (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2015, 46, 907–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Moon, H.-J.; Park, S.-Y.; Lee, S.-H.; Kang, C.-D.; Kim, S.-H. Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs Sensitize CD44-Overexpressing Cancer Cells to Hsp90 Inhibitor Through Autophagy Activation. Oncol. Res. 2019, 27, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-C.; Chang, W.-W.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Tsai, Y.-H.; Chou, Y.-H.; Tseng, H.-C.; Chen, H.-L.; Wu, C.-C.; Chang-Chien, J.; Lee, H.-T.; et al. Hsp90α Mediates BMI1 Expression in Breast Cancer Stem/Progenitor Cells through Facilitating Nuclear Translocation of c-Myc and EZH2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, K.S.; Kim, G.P.; Foster, N.R.; Wang-Gillam, A.; Erlichman, C.; McWilliams, R.R. Phase II Trial of Gemcitabine and Tanespimycin (17AAG) in Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer: A Mayo Clinic Phase II Consortium Study. Investig. New Drugs 2015, 33, 963–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.J.; Chugh, R.; Rosen, L.S.; Morgan, J.A.; George, S.; Gordon, M.; Dunbar, J.; Normant, E.; Grayzel, D.; Demetri, G.D. A Phase I Study of the HSP90 Inhibitor Retaspimycin Hydrochloride (IPI-504) in Patients with Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors or Soft-Tissue Sarcomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 6020–6029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Luke, J.J.; Jacene, H.A.; Chen, T.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Ibrahim, N.; Buchbinder, E.L.; McDermott, D.F.; Flaherty, K.T.; Sullivan, R.J.; et al. Results from Phase II Trial of HSP90 Inhibitor, STA-9090 (Ganetespib), in Metastatic Uveal Melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2018, 28, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroglu, Z.; Chen, Y.A.; Gibney, G.T.; Weber, J.S.; Kudchadkar, R.R.; Khushalani, N.I.; Markowitz, J.; Brohl, A.S.; Tetteh, L.F.; Ramadan, H.; et al. Combined BRAF and HSP90 Inhibition in Patients with Unresectable BRAF V600E-Mutant Melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 5516–5524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, S.M. Pimitespib: First Approval. Drugs 2022, 82, 1413–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cierpikowski, P.; Bar, J. Heat Shock Proteins in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cells 2025, 14, 1897. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231897

Cierpikowski P, Bar J. Heat Shock Proteins in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cells. 2025; 14(23):1897. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231897

Chicago/Turabian StyleCierpikowski, Piotr, and Julia Bar. 2025. "Heat Shock Proteins in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma" Cells 14, no. 23: 1897. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231897

APA StyleCierpikowski, P., & Bar, J. (2025). Heat Shock Proteins in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cells, 14(23), 1897. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231897