cGAS/STING Pathway Mediates Accelerated Intestinal Cell Senescence and SASP After GCR Exposure in Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Irradiation and Biospecimen Collection

2.2. Crypt Cells Isolation and Senescent Cell Detection

2.3. Immunostaining

2.4. Immunoblot Analysis

2.5. qPCR Assays and Serum DNA Detection

2.6. Barrier Function Analysis

2.7. Imaging, Quantification, and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. GCRsim Induces DNA Double-Strand Breaks and Enhances Lipid Peroxidation

3.2. GCRsim Induces Senescence and Acquisition of Senescence Associated Secretory Phenotype

3.3. GCRsim Exposure Increases Circulating LINE-1 DNA and Reduces Nuclease Expression

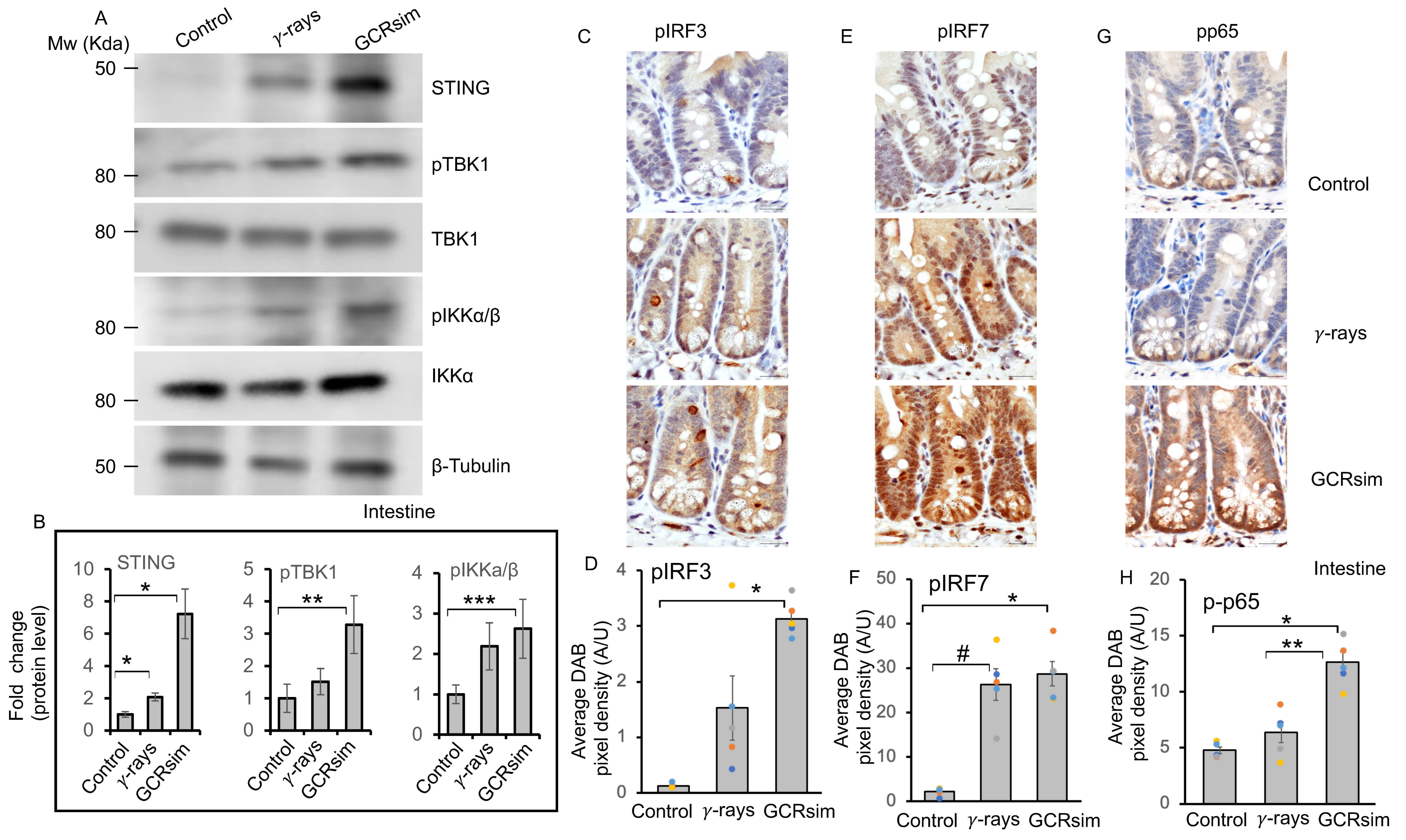

3.4. GCRsim Exposure Induces Sustained Activation of the cGAS–STING Pathway in the Mouse Intestine

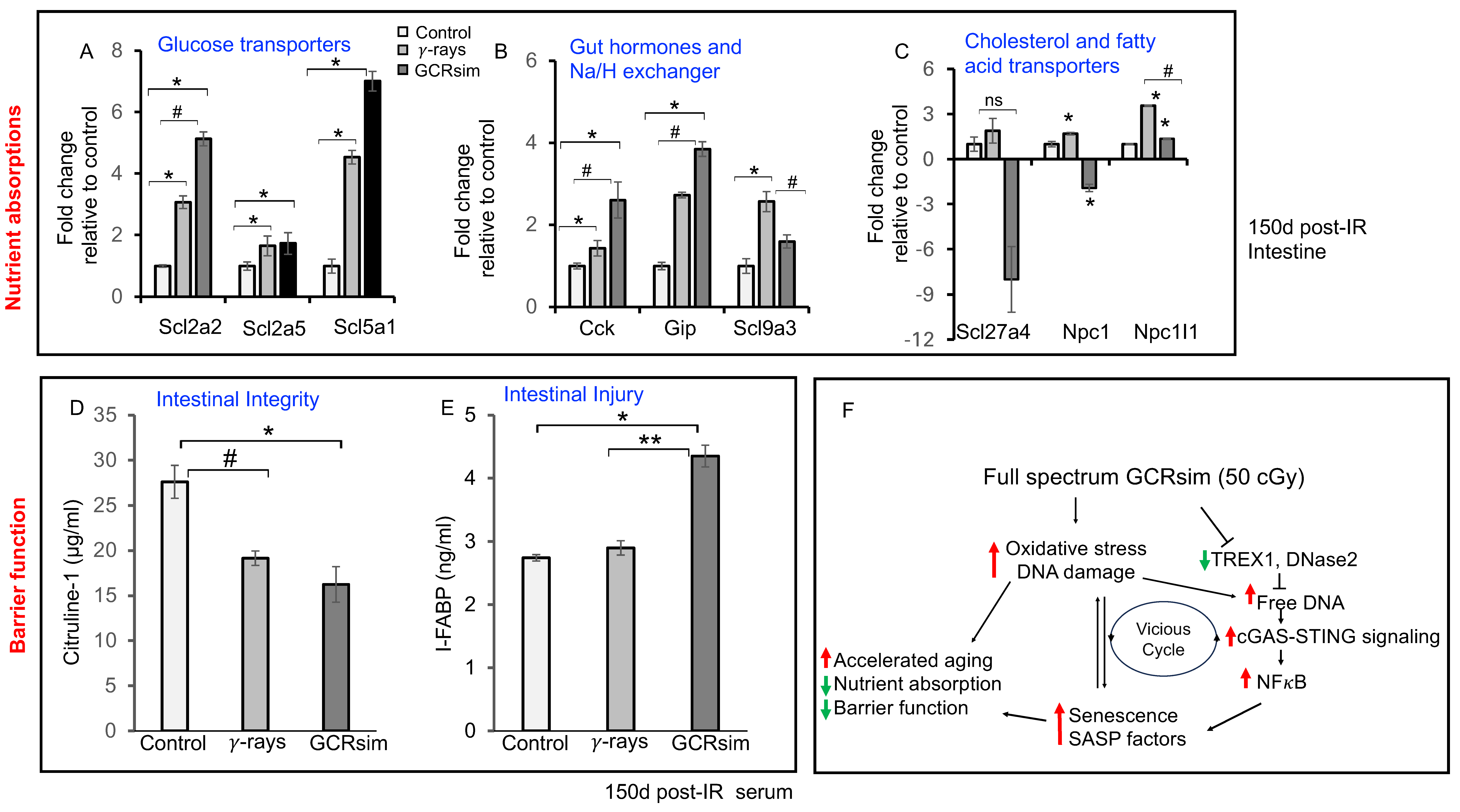

3.5. GCRsim Exposure Perturbs Nutrient Absorption and Intestinal Barrier Integrity in Mouse Gut

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| IECs | Intestinal epithelial cells |

| GCRsim | Galactic cosmic radiation simulation |

| SPEs | Solar Particle events |

| GRBs | Gamma ray bursts |

| HZE | High atomic number and high energy |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| DSBs | DNA double strand breaks |

| LINE1 | Long interspersed nuclear element 1 |

| SASP | Senescence-associated secretory phenotype |

| cGAS | Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase |

| STING | Stimulator of Interferon Genes |

| IRF | Interferon Regulatory Factor |

| IL | Interleukin |

| CXCL | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) Ligand |

| ICAM | Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

References

- Norbury, J.W.; Schimmerling, W.; Slaba, T.C.; Azzam, E.I.; Badavi, F.F.; Baiocco, G.; Benton, E.; Bindi, V.; Blakely, E.A.; Blattnig, S.R.; et al. Galactic cosmic ray simulation at the NASA Space Radiation Laboratory. Life Sci. Space Res. 2016, 8, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmanian, S.; Slaba, T.C.; George, S.; Braby, L.A.; Bhattacharya, S.; Straume, T.; Santa Maria, S.R. Galactic cosmic ray environment predictions for the NASA BioSentinel Mission, part 2: Post-mission validation. Life Sci. Space Res. 2025, 44, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonsen, L.C.; Slaba, T.C.; Guida, P.; Rusek, A. NASA’s first ground-based Galactic Cosmic Ray Simulator: Enabling a new era in space radiobiology research. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz, J.; Kuhlman, B.M.; Edenhoffer, N.P.; Evans, A.C.; Martin, K.A.; Guida, P.; Rusek, A.; Atala, A.; Coleman, M.A.; Wilson, P.F.; et al. Immediate effects of acute Mars mission equivalent doses of SEP and GCR radiation on the murine gastrointestinal system-protective effects of curcumin-loaded nanolipoprotein particles (cNLPs). Front. Astron. Space Sci. 2023, 10, 1117811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zeitlin, C.; Wimmer-Schweingruber, R.F.; Hassler, D.M.; Ehresmann, B.; Rafkin, S.; Freiherr von Forstner, J.L.; Khaksarighiri, S.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y. Radiation environment for future human exploration on the surface of Mars: The current understanding based on MSL/RAD dose measurements. Astron. Astrophys. Rev. 2021, 29, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Kumar, S.; Angdisen, J.; Datta, K.; Fornace, A.J.; Suman, S. Radiation Quality-Dependent Progressive Increase in Oxidative DNA Damage and Intestinal Tumorigenesis in Apc1638N/+ Mice. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Suman, S.; Fornace, A.J.; Datta, K. Space radiation triggers persistent stress response, increases senescent signaling, and decreases cell migration in mouse intestine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Suman, S.; Fornace, A.J.; Datta, K. Intestinal stem cells acquire premature senescence and senescence associated secretory phenotype concurrent with persistent DNA damage after heavy ion radiation in mice. Aging 2019, 11, 4145–4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Kumar, S.; Datta, K.; Fornace, A.J.; Suman, S. High-LET-Radiation-Induced Persistent DNA Damage Response Signaling and Gastrointestinal Cancer Development. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 5497–5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, S.; Kumar, S.; Moon, B.-H.; Strawn, S.J.; Thakor, H.; Fan, Z.; Shay, J.W.; Fornace, A.J., Jr.; Datta, K. Relative Biological Effectiveness of Energetic Heavy Ions for Intestinal Tumorigenesis Shows Male Preponderance and Radiation Type and Energy Dependence in APC1638N/+ Mice. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2016, 95, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Suman, S.; Moon, B.-H.; Fornace, A.J.; Datta, K. Low dose radiation upregulates Ras/p38 and NADPH oxidase in mouse colon two months after exposure. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 2067–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzam, E.I.; Jay-Gerin, J.-P.; Pain, D. Ionizing radiation-induced metabolic oxidative stress and prolonged cell injury. Cancer Lett. 2012, 327, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Suman, S.; Angdisen, J.; Moon, B.-H.; Kallakury, B.V.S.; Datta, K.; Fornace, A.J., Jr. Effects of High-Linear-Energy-Transfer Heavy Ion Radiation on Intestinal Stem Cells: Implications for Gut Health and Tumorigenesis. Cancers 2024, 16, 3392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koturbash, I. LINE-1 in response to exposure to ionizing radiation. Mob. Genet. Elem. 2017, 7, e1393491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, A.; Nakatani, Y.; Hamada, N.; Jinno-Oue, A.; Shimizu, N.; Wada, S.; Funayama, T.; Mori, T.; Islam, S.; Hoque, S.A.; et al. Ionising irradiation alters the dynamics of human long interspersed nuclear elements 1 (LINE1) retrotransposon. Mutagenesis 2012, 27, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathavarajah, S.; Dellaire, G. LINE-1: An emerging initiator of cGAS-STING signalling and inflammation that is dysregulated in disease. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2024, 102, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhao, H.; Shen, Y.; Chen, Q. A Variety of Nucleic Acid Species Are Sensed by cGAS, Implications for Its Diverse Functions. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Moon, B.H.; Datta, K.; Fornace, A.J.; Suman, S. Simulated galactic cosmic radiation (GCR)-induced expression of Spp1 coincide with mammary ductal cell proliferation and preneoplastic changes in ApcMin/+ mouse. Life Sci. Space Res. 2023, 36, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, J.L.; Poignant, F.; Rahmanian, S.; Khan, N.; Blakely, E.A.; Britten, R.A.; Chang, P.; Fornace, A.J.; Hada, M.; Kronenberg, A.; et al. Galactic cosmic ray simulation at the NASA space radiation laboratory—Progress, challenges and recommendations on mixed-field effects. Life Sci. Space Res. 2023, 36, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-H.Y.; Rusek, A.; Cucinotta, F.A. Issues for Simulation of Galactic Cosmic Ray Exposures for Radiobiological Research at Ground-Based Accelerators. Front. Oncol. 2015, 5, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, A.; Yu, C.; Bratman, S.V. Serial Cell-free DNA Assessments in Preclinical Models. STAR Protoc. 2020, 1, 100145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunami, E.; Vu, A.; Nguyen, S.L.; Giuliano, A.E.; Hoon, D.S.B. Quantification of LINE1 in Circulating DNA as a Molecular Biomarker of Breast Cancer. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1137, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwiatkowski, E.; Suman, S.; Kallakury, B.V.S.; Datta, K.; Fornace, A.J.; Kumar, S. Expression of Stem Cell Markers in High-LET Space Radiation-Induced Intestinal Tumors in Apc1638N/+ Mouse Intestine. Cancers 2023, 15, 4240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niki, E. Lipid peroxidation products as oxidative stress biomarkers. BioFactors 2008, 34, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praticò, D. Lipid Peroxidation and the Aging Process. Sci. Aging Knowl. Environ. 2002, 2002, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HANBAUER, I.N.G.E.B.O.R.G.; SCORTEGAGNA, M.A.R.Z.I.A. Molecular Markers of Oxidative Stress Vulnerability. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000, 899, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patchsung, M.; Boonla, C.; Amnattrakul, P.; Dissayabutra, T.; Mutirangura, A.; Tosukhowong, P. Long Interspersed Nuclear Element-1 Hypomethylation and Oxidative Stress: Correlation and Bladder Cancer Diagnostic Potential. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbstein, F.; Sapochnik, M.; Attorresi, A.; Pollak, C.; Senin, S.; Gonilski-Pacin, D.; Ciancio del Giudice, N.; Fiz, M.; Elguero, B.; Fuertes, M.; et al. The SASP factor IL-6 sustains cell-autonomous senescent cells via a cGAS-STING-NFκB intracrine senescent noncanonical pathway. Aging Cell 2024, 23, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, T.M.; Miyata, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Takahashi, A. Cellular senescence and senescence-associated secretory phenotype via the cGAS-STING signaling pathway in cancer. Cancer Sci. 2020, 111, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, C.R.R.; Maurmann, R.M.; Guma, F.T.C.R.; Bauer, M.E.; Barbé-Tuana, F.M. cGAS-STING pathway as a potential trigger of immunosenescence and inflammaging. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macleod, T.; Berekmeri, A.; Bridgewood, C.; Stacey, M.; McGonagle, D.; Wittmann, M. The Immunological Impact of IL-1 Family Cytokines on the Epidermal Barrier. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Dong, L.; Lv, Q.; Yin, Y.; Zhao, J.; Ke, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, W.; Wu, M. Targeting senescence-associated secretory phenotypes to remodel the tumour microenvironment and modulate tumour outcomes. Clin. Transl. Med. 2024, 14, e1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macia, A.; Tejwani, L.; Mesci, P.; Muotri, A.; Garcia-Perez, J.L. Activity of Retrotransposons in Stem Cells and Differentiated Cells. In Human Retrotransposons in Health and Disease; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 127–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, K.S.; Teneng, I.; Montoya-Durango, D.E.; Bojang, P.; Haeberle, M.T.; Ramos, I.N.; Stribinskis, V.; Kalbfleisch, T. The Intersection of Genetics and Epigenetics: Reactivation of Mammalian LINE-1 Retrotransposons by Environmental Injury. In Epigenetics and Human Health: Environmental Epigenomics in Health and Disease; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 127–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.; Butt, A.; Cahill, D.; Wheeler, M.; Popert, R.; Swaminathan, R. Role of Cell-Free Plasma DNA as a Diagnostic Marker for Prostate Cancer. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004, 1022, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Martino, M.; Klatte, T.; Haitel, A.; Marberger, M. Serum cell-free DNA in renal cell carcinoma: A diagnostic and prognostic marker. Cancer 2012, 118, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, F.; Guorong, L.; An, Z.; Anne, G.-P.; Christian, G.; Jacques, T. Prediction of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma by Integrity of Cell-free DNA in Serum. Urology 2010, 75, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopfner, K.-P.; Hornung, V. Molecular mechanisms and cellular functions of cGAS–STING signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 501–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belli, M.; Tabocchini, M.A. Ionizing Radiation-Induced Epigenetic Modifications and Their Relevance to Radiation Protection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANDERSEN, M.O.N.I.C.A.L.; WINTER, L.U.C.I.L.E.M.F. Animal models in biological and biomedical research—Experimental and ethical concerns. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2019, 91, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Oliva, A.; Hernández-Ávalos, I.; Martínez-Burnes, J.; Olmos-Hernández, A.; Verduzco-Mendoza, A.; Mota-Rojas, D. The Importance of Animal Models in Biomedical Research: Current Insights and Applications. Animals 2023, 13, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellweg, C.E.; Berger, T.; Matthiä, D.; Baumstark-Khan, C. Radiation in Space: Relevance and Risk for Human Missions; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straume, T. Space Radiation Effects on Crew During and After Deep Space Missions. Curr. Pathobiol. Rep. 2018, 6, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strigari, L.; Strolin, S.; Morganti, A.G.; Bartoloni, A. Dose-Effects Models for Space Radiobiology: An Overview on Dose-Effect Relationships. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, S.; Kumar, S.; Moon, B.-H.; Fornace, A.J.; Datta, K. Low and high dose rate heavy ion radiation-induced intestinal and colonic tumorigenesis in APC1638N/+ mice. Life Sci. Space Res. 2017, 13, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, K.; Moradi, M.; Vossoughi, B.; Janabadi, E.D. Space-technological and architectural methodology and process towards design of long-term habitats for scientific human missions on mars. MethodsX 2023, 11, 102270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobney, W.; Mols, L.; Mistry, D.; Tabury, K.; Baselet, B.; Baatout, S. Evaluation of deep space exploration risks and mitigations against radiation and microgravity. Front. Nucl. Med. 2023, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatagai, F.; Honma, M.; Dohmae, N.; Ishioka, N. Biological effects of space environmental factors: A possible interaction between space radiation and microgravity. Life Sci. Space Res. 2019, 20, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naito, M.; Kodaira, S. Considerations for practical dose equivalent assessment of space radiation and exposure risk reduction in deep space. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeitlin, C.; La Tessa, C. The Role of Nuclear Fragmentation in Particle Therapy and Space Radiation Protection. Front. Oncol. 2016, 6, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kumar, S.; Kumar, K.; Angdisen, J.; Suman, S.; Kallakury, B.V.S.; Fornace, A.J., Jr. cGAS/STING Pathway Mediates Accelerated Intestinal Cell Senescence and SASP After GCR Exposure in Mice. Cells 2025, 14, 1767. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14221767

Kumar S, Kumar K, Angdisen J, Suman S, Kallakury BVS, Fornace AJ Jr. cGAS/STING Pathway Mediates Accelerated Intestinal Cell Senescence and SASP After GCR Exposure in Mice. Cells. 2025; 14(22):1767. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14221767

Chicago/Turabian StyleKumar, Santosh, Kamendra Kumar, Jerry Angdisen, Shubhankar Suman, Bhaskar V. S. Kallakury, and Albert J. Fornace, Jr. 2025. "cGAS/STING Pathway Mediates Accelerated Intestinal Cell Senescence and SASP After GCR Exposure in Mice" Cells 14, no. 22: 1767. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14221767

APA StyleKumar, S., Kumar, K., Angdisen, J., Suman, S., Kallakury, B. V. S., & Fornace, A. J., Jr. (2025). cGAS/STING Pathway Mediates Accelerated Intestinal Cell Senescence and SASP After GCR Exposure in Mice. Cells, 14(22), 1767. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14221767