Muscle-Bone Crosstalk and Metabolic Dysregulation in Children and Young People Affected with Type 1 Diabetes: Mechanisms and Clinical Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Cellular Mechanism of Muscle Skeletal Impairment

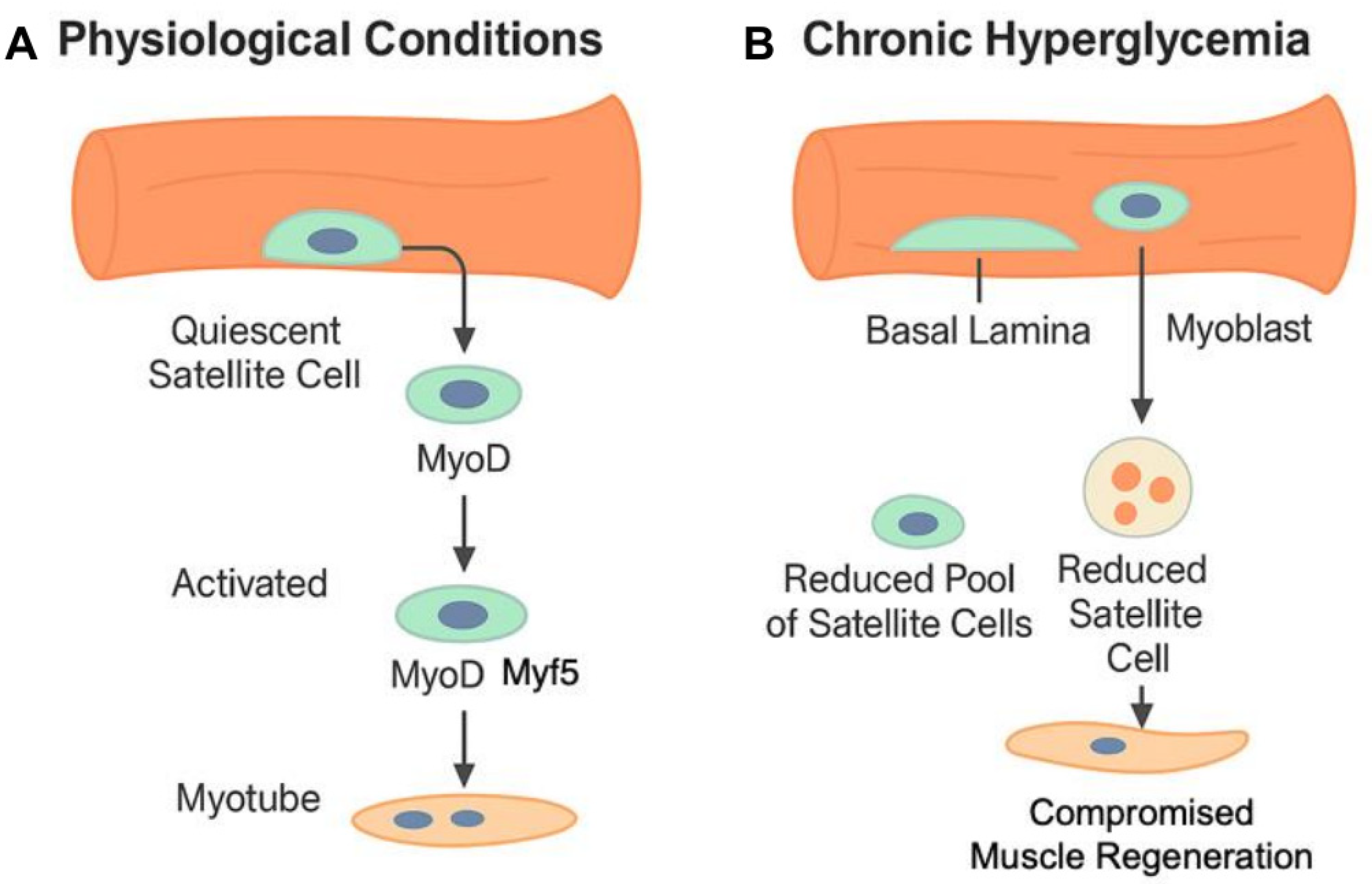

2.1. Impairment of Satellite Cells

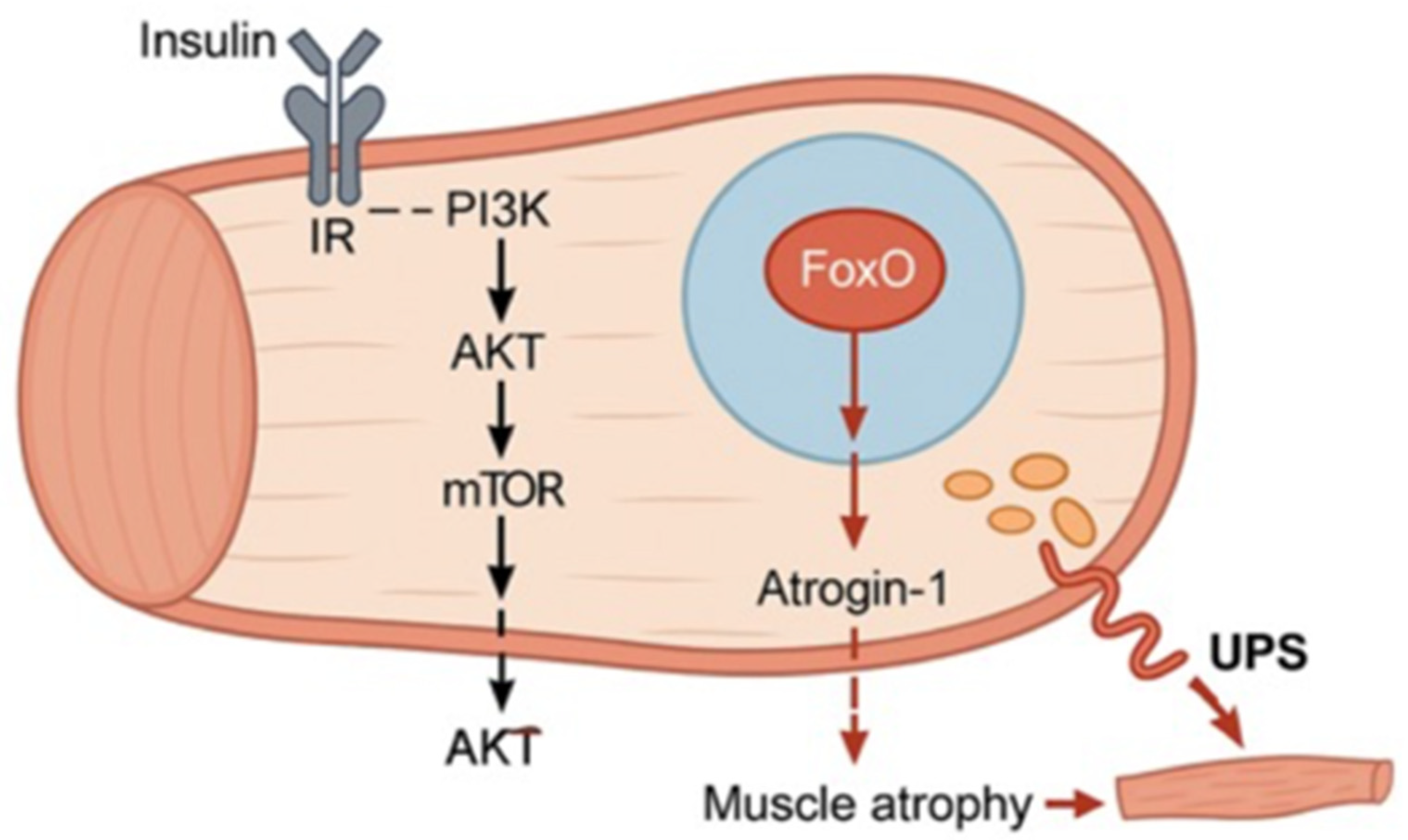

2.2. Insulin Alteration

2.3. Accumulation of Advanced Glycation End-Products (AGEs)

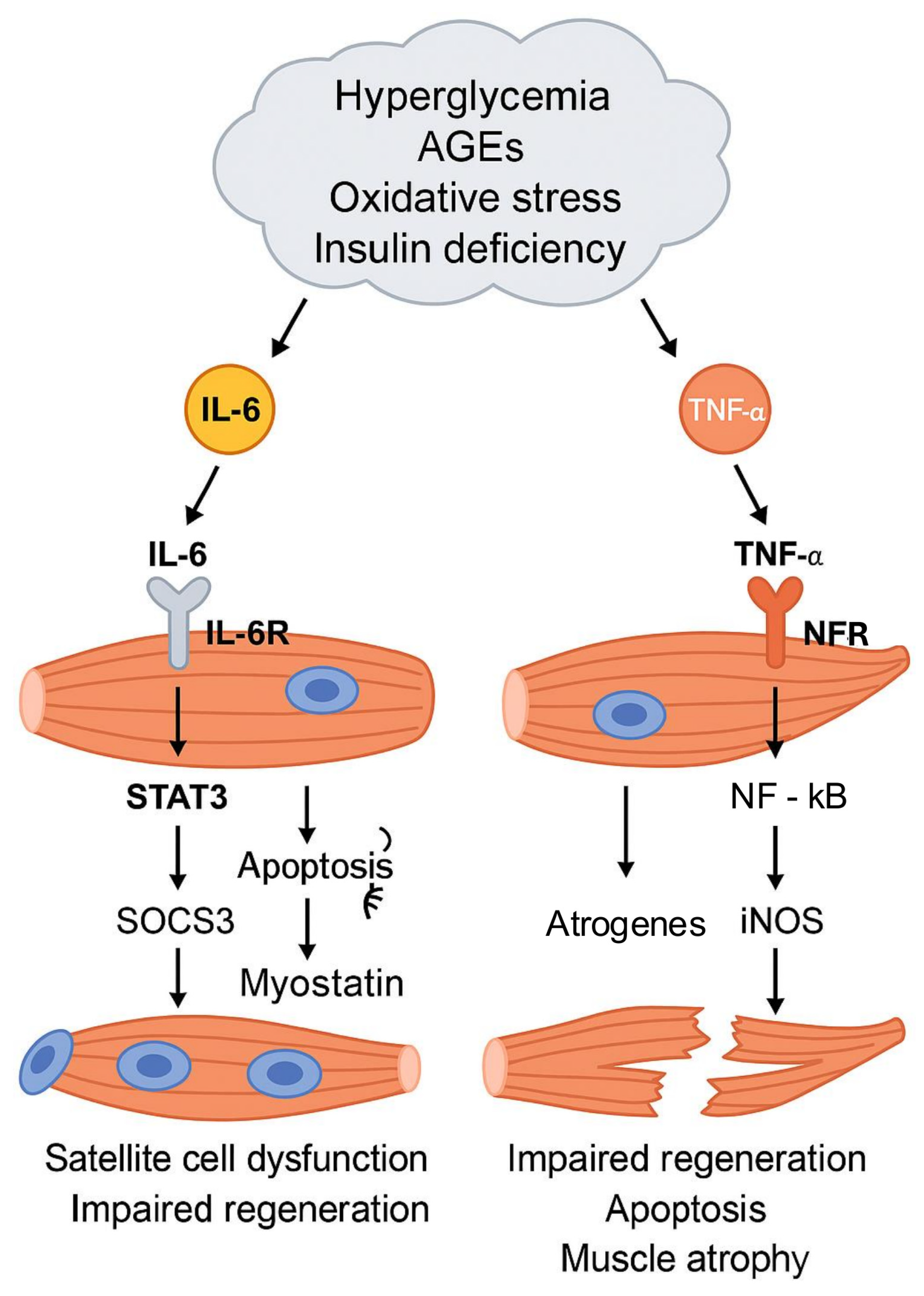

2.4. Inflammation

3. Cellular Mechanism of Bone Impairment

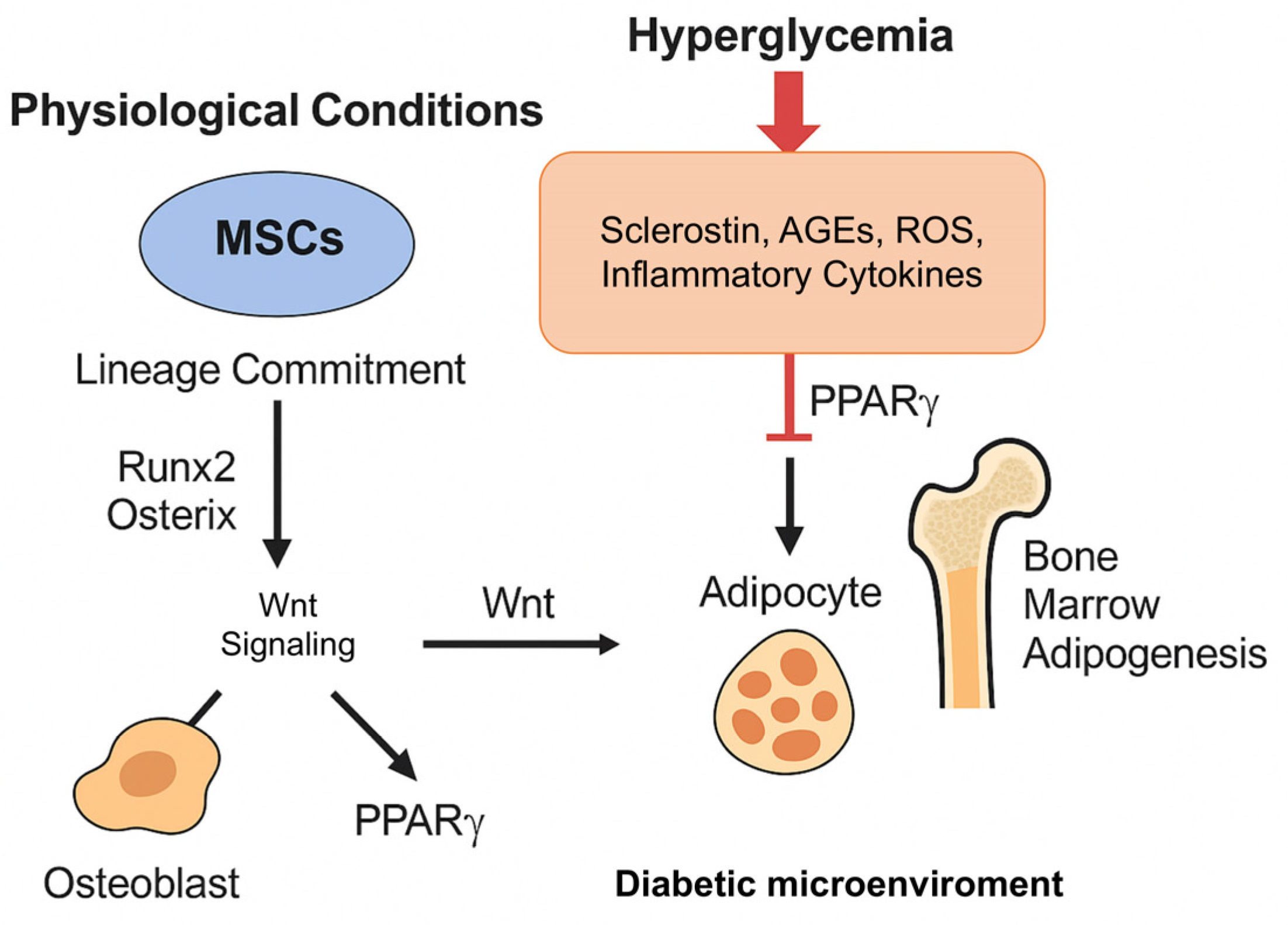

3.1. Hyperglycemia and Mesenchymal Stromal Cells

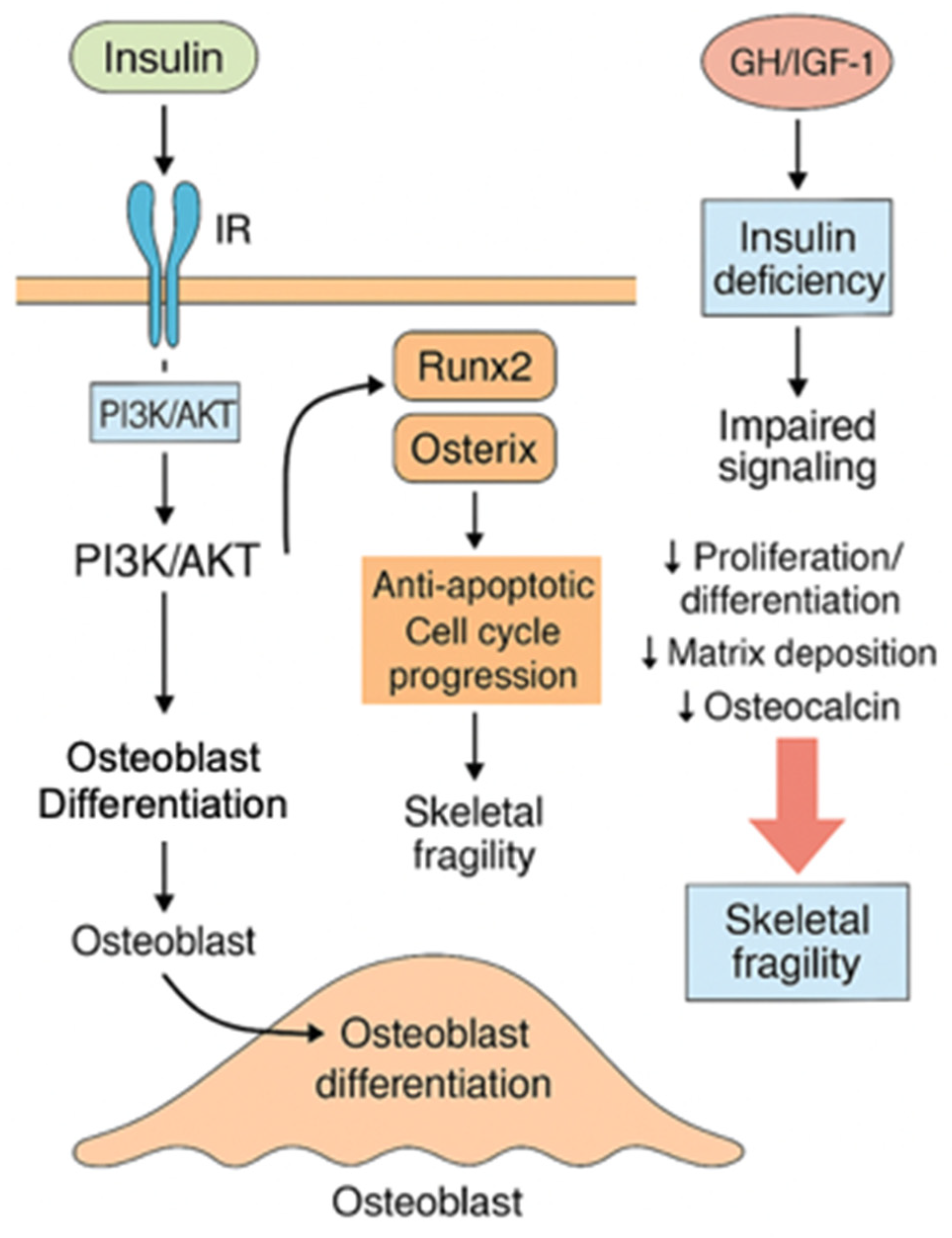

3.2. Insulin and the GH/IGF-1 Axis

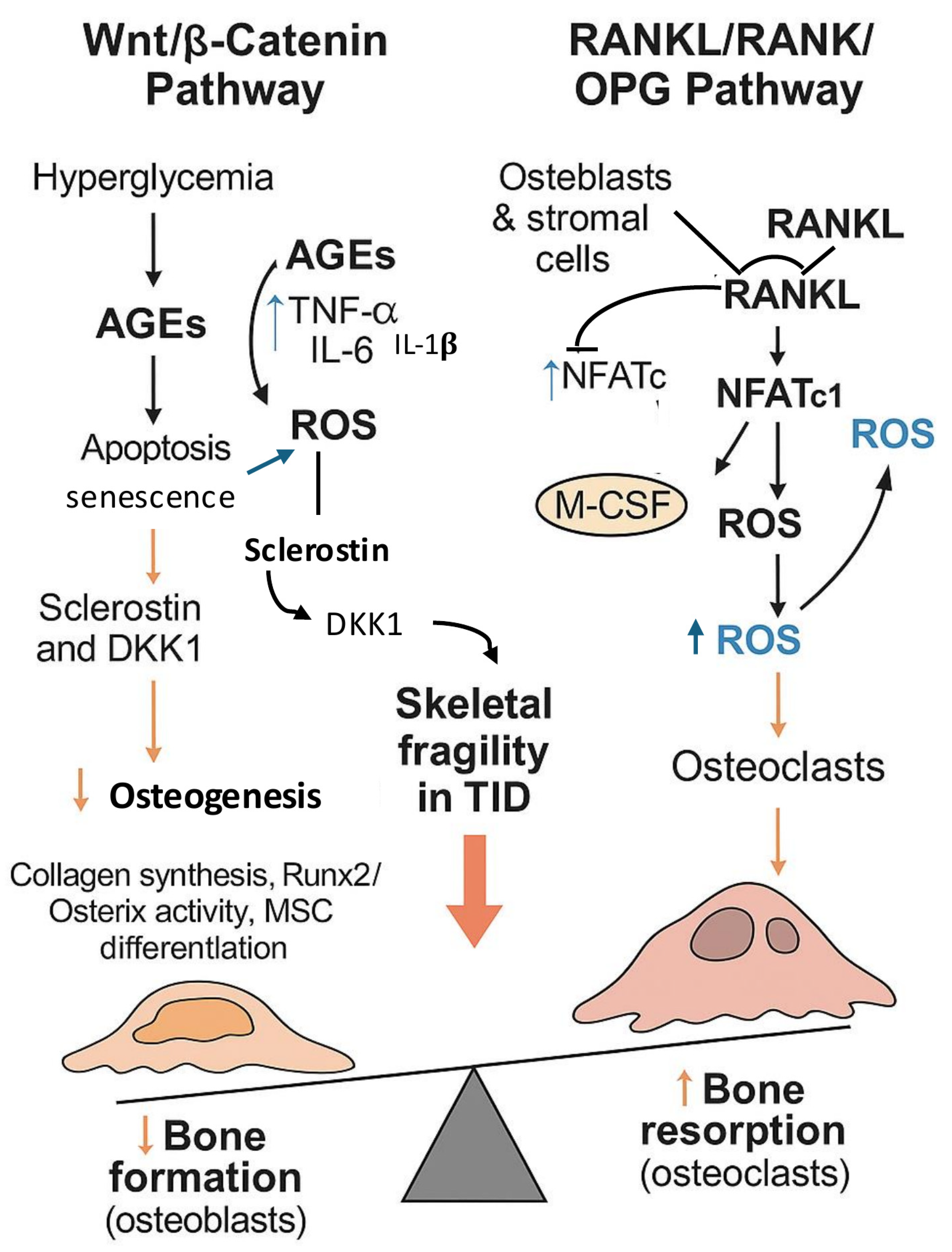

3.3. Wnt/β-Catenin and RANKL/RANK/OPG Pathways

3.4. “Metabolic Memory” and Mitochondrial Dysfunction

4. Insights from Human Studies on Muscle Skeletal and Bone Impairment

5. Prevention and Treatment

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| T1DM | Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus |

| HbA1c | Hemoglobin A1c |

| CGM | Continuous Glucose Monitoring |

| CSII | Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion |

| MDI | Multiple Daily Injections |

| BMD | Bone Mineral Density |

| BMC | Bone Mineral Content |

| aBMD | Areal Bone Mineral Density |

| DXA | Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry |

| pQCT | Peripheral Quantitative Computed Tomography |

| AGEs | Advanced Glycation End-products |

| RAGE | Receptor for Advanced Glycation End-products |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase |

| AKT | Protein Kinase B |

| mTOR | Mammalian Target of Rapamycin |

| FoxO | Forkhead Box O |

| MuRF1 | Muscle-specific RING Finger Protein 1 |

| UPS | Ubiquitin–Proteasome System |

| IR | Insulin Receptor |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 |

| IGF1R | Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 Receptor |

| PGC1α | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Coactivator 1-Alpha |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| ERK | Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase |

| JAK | Janus Kinase |

| STAT | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa B |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 Beta |

| SOCS3 | Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling 3 |

| GLUT4 | Glucose Transporter Type 4 |

| IKK | IκB Kinase |

| iNOS | Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| DKK1 | Dickkopf-1 |

| RANKL | Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor Kappa-B Ligand |

| RANK | Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor Kappa-B |

| OPG | Osteoprotegerin |

| GH | Growth Hormone |

| MSCs | Mesenchymal Stromal Cells |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma |

| C/EBPα | CCAAT/Enhancer-Binding Protein Alpha |

| AP-1 | Activator Protein 1 |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| DNMT | DNA Methyltransferase |

| HAT | Histone Acetyltransferase |

| HDAC | Histone Deacetylase |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| DKA | Diabetic Ketoacidosis |

| THIN | The Health Improvement Network |

| ISPAD | International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes |

References

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 8th ed.; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Urbano, F.; Farella, I.; Brunetti, G.; Faienza, M.F. Pediatric type 1 diabetes: Mechanisms and impact of technologies on comorbidities and life expectancy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faienza, M.F.; Scicchitano, P.; Lamparelli, R.; Zaza, P.; Cecere, A.; Brunetti, G.; Cortese, F.; Valente, F.; Delvecchio, M.; Giordano, P. Vascular and myocardial function in young people with type 1 diabetes mellitus: Insulin pump therapy versus multiple daily injections insulin regimen. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2022, 130, 415–422. [Google Scholar]

- Rawshani, A.; Rawshani, A.; Gudbjörnsdottir, S. Mortality and cardiovascular disease in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 300–301. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Xie, M.; Liu, Q.; Li, S. Vascular complications of diabetes: A narrative review. Medicine 2023, 102, e35285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travis, C.; Srivastava, P.S.; Hawke, T.J.; Kalaitzoglou, E. Diabetic bone disease and diabetic myopathy: Manifestations of the impaired muscle-bone unit in type 1 diabetes. J. Diabetes Res. 2022, 2022, 2650342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hough, F.S.; Pierroz, D.D.; Cooper, C.; Ferrari, S.L.; IOF CSA Bone and Diabetes Working Group. Mechanisms and evaluation of bone fragility in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2016, 174, R127–R138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, H.M.; Schönau, E. The muscle-bone unit in children and adolescents: A 2000 overview. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 13, 571–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuichi, Y.; Kawabata, Y.; Aoki, M.; Mita, Y.; Fujii, N.L.; Manabe, Y. Excess glucose impedes the proliferation of skeletal muscle satellite cells under adherent culture conditions. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 640399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammit, P.S.; Relaix, F.; Nagata, Y.; Ruiz, A.P.; Collins, C.A.; Partridge, T.A.; Beauchamp, J.R. Pax7 and myogenic progression in skeletal muscle satellite cells. J. Cell Sci. 2006, 119, 1824–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rampalli, S.; Li, L.; Mak, E.; Ge, K.; Brand, M.; Tapscott, S.J.; Dilworth, F.J. p38 MAPK signaling regulates recruitment of Ash2L-containing methyltransferase complexes to specific genes during differentiation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007, 14, 1150–1156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Badu-Mensah, A.; Valinski, P.; Parsaud, H.; Hickman, J.J.; Guo, X. Hyperglycemia negatively affects iPSC-derived myoblast proliferation and skeletal muscle regeneration and function. Cells 2022, 11, 3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, C.M.; Emanuelli, B.; Kahn, C.R. Critical nodes in signalling pathways: Insights into insulin action. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakravarthy, M.V.; Abraha, T.W.; Schwartz, R.J.; Fiorotto, M.L.; Booth, F.W. Insulin-like growth factor-I extends in vitro replicative life span of skeletal muscle satellite cells by enhancing G1/S cell cycle progression via the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase/Akt signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 35942–35952. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, R.A.; Lang, C.H. Multifaceted role of insulin-like growth factors and mammalian target of rapamycin in skeletal muscle. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2012, 41, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, B.T.; Bhardwaj, G.; Penniman, C.M.; Krumpoch, M.T.; Suarez Beltran, P.A.; Klaus, K.; Poro, K.; Li, M.; Pan, H.; Dreyfuss, J.M.; et al. FoxO transcription factors are critical regulators of diabetes-related muscle atrophy. Diabetes 2019, 68, 556–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stitt, T.N.; Drujan, D.; Clarke, B.A.; Panaro, F.; Timofeyva, Y.; Kline, W.O.; Gonzalez, M.; Yancopoulos, G.D.; Glass, D.J. The IGF-1/PI3K/Akt pathway prevents expression of muscle atrophy-induced ubiquitin ligases by inhibiting FOXO transcription factors. Mol. Cell 2004, 14, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Li, N.; Jia, W.; Wang, N.; Liang, M.; Yang, X.; Du, G. Skeletal muscle atrophy: From mechanisms to treatments. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 172, 105807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, D.J. Signalling pathways that mediate skeletal muscle hypertrophy and atrophy. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2003, 5, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milan, G.; Romanello, V.; Pescatore, F.; Armani, A.; Paik, J.-H.; Frasson, L.; Seydel, A.; Zhao, J.; Abraham, R.; Goldberg, A.L.; et al. Regulation of autophagy and the ubiquitin–proteasome system by the FoxO transcriptional network during muscle atrophy. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negre-Salvayre, A.; Salvayre, R.; Augé, N.; Pamplona, R.; Portero-Otín, M. Hyperglycemia and glycation in diabetic complications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 3071–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uceda, A.B.; Mariño, L.; Casasnovas, R.; Adrover, M. An overview on glycation: Molecular mechanisms, impact on proteins, pathogenesis, and inhibition. Biophys. Rev. 2024, 16, 189–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramasamy, R.; Vannucci, S.J.; Yan, S.S.D.; Herold, K.; Yan, S.F.; Schmidt, A.M. Advanced glycation end products and RAGE: A common thread in aging, diabetes, neurodegeneration, and inflammation. Glycobiology 2005, 15, 16R–28R. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.F.; Ramasamy, R.; Schmidt, A.M. The RAGE axis: A fundamental mechanism signaling danger to the vulnerable vasculature. Circ. Res. 2010, 106, 842–853. [Google Scholar]

- Neeper, M.; Schmidt, A.M.; Brett, J.; Yan, S.D.; Wang, F.; Pan, Y.; Elliston, K.; Stern, D.; Shaw, A. Cloning and expression of a cell surface receptor for advanced glycosylation end products of proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 14998–15004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riuzzi, F.; Sorci, G.; Sagheddu, R.; Chiappalupi, S.; Salvadori, L.; Donato, R. RAGE in the pathophysiology of skeletal muscle. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2018, 9, 1213–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serban, A.I.; Stanca, L.; Geicu, O.I.; Munteanu, M.C.; Dinischiotu, A. RAGE and TGF-β1 cross-talk regulate extracellular matrix turnover and cytokine synthesis in AGEs exposed fibroblast cells. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svensson, R.B.; Smith, S.T.; Moyer, P.J.; Magnusson, S.P. Effects of maturation and advanced glycation on tensile mechanics of collagen fibrils from rat tail and Achilles tendons. Acta Biomater. 2018, 70, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, L.C.; Redden, J.T.; Schwartz, Z.; Cohen, D.J.; McClure, M.J. Advanced glycation end-products in skeletal muscle aging. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloseris, D.; Forde, N.R. AGEing of collagen: The effects of glycation on collagen’s stability, mechanics and assembly. Matrix Biol. 2025, 135, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Hayashi, T.; Egawa, T. Advanced glycation end products promote ROS production via PKC/p47phox axis in skeletal muscle cells. J. Physiol. Sci. 2024, 74, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcina, L.; Miano, C.; Musarò, A. The physiopathologic interplay between stem cells and tissue niche in muscle regeneration and the role of IL-6 on muscle homeostasis and diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2018, 41, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurosaka, M.; Machida, S. Interleukin-6-induced satellite cell proliferation is regulated by induction of the JAK2/STAT3 signalling pathway through cyclin D1 targeting. Cell Prolif. 2013, 46, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharjee, S.; Ghosh, B.; Al-Dhubiab, B.E.; Nair, A.B. Understanding type 1 diabetes: Etiology and models. Can. J. Diabetes 2013, 37, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonetto, A.; Aydogdu, T.; Jin, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhan, R.; Puzis, L.; Koniaris, L.G.; Zimmers, T.A. JAK/STAT3 pathway inhibition blocks skeletal muscle wasting downstream of IL-6 and in experimental cancer cachexia. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 303, E410–E421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emanuelli, B.; Glondu, M.; Filloux, C.; Peraldi, P.; Van Obberghen, E. The potential role of SOCS-3 in the interleukin-1β-induced desensitization of insulin signaling in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes 2004, 53, S97–S103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaspelkis, B.B.; Kvasha, I.A.; Figueroa, T.Y. High-fat feeding increases insulin receptor and IRS-1 coimmunoprecipitation with SOCS-3, IKKα/β phosphorylation and decreases PI-3 kinase activity in muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2009, 296, R1709–R1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, K.; Rønn, S.G.; Tornehave, D.; Richter, H.; Hansen, J.A.; Rømer, J.; Jackerott, M.; Billestrup, N. Regulation of pancreatic β-cell mass and proliferation by SOCS-3. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005, 35, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léger, B.; Derave, W.; De Bock, K.; Hespel, P.; Russell, A.P. Human sarcopenia reveals an increase in SOCS-3 and myostatin and a reduced efficiency of Akt phosphorylation. Rejuvenation Res. 2008, 11, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plomgaard, P.; Bouzakri, K.; Krogh-Madsen, R.; Mittendorfer, B.; Zierath, J.R.; Pedersen, B.K. Tumor necrosis factor-α induces skeletal muscle insulin resistance in healthy human subjects via inhibition of Akt substrate 160 phosphorylation. Diabetes 2005, 54, 2939–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Alvaro, C.; Teruel, T.; Hernandez, R.; Lorenzo, M. Tumor necrosis factor α produces insulin resistance in skeletal muscle by activation of inhibitor κB kinase in a p38 MAPK-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 17070–17078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddai, V.; Jager, J.; Gonzalez, T.; Najem-Lendom, R.; Bonnafous, S.; Tran, A.; Le Marchand-Brustel, Y.; Gual, P.; Tanti, J.-F.; Cormont, M. Involvement of TNF-α in abnormal adipocyte and muscle sortilin expression in obese mice and humans. Diabetologia 2009, 52, 932–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, J.M.; Lee, J.; Pilch, P.F. Tumor necrosis factor-α-induced insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes is accompanied by a loss of insulin receptor substrate-1 and GLUT4 expression without a loss of insulin receptor-mediated signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 971–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.-P.; Chen, Y.; John, J.; Moylan, J.; Jin, B.; Mann, D.L.; Reid, M.B. TNF-α acts via p38 MAPK to stimulate expression of the ubiquitin ligase atrogin1/MAFbx in skeletal muscle. FASEB J. 2005, 19, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackman, R.W.; Cornwell, E.W.; Wu, C.; Kandarian, S.C. Nuclear factor-κB signalling and transcriptional regulation in skeletal muscle atrophy. Exp. Physiol. 2013, 98, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Frantz, J.D.; Tawa, N.E.; Melendez, P.A.; Oh, B.C.; Lidov, H.G.W.; Hasselgren, P.-O.; Frontera, W.R.; Lee, J.; Glass, D.J.; et al. IKKβ/NF-κB activation causes severe muscle wasting in mice. Cell 2004, 119, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.F.; Sanchez, B.J.; Hall, D.T.; Tremblay, A.K.; Di Marco, S.; Gallouzi, I. STAT3 promotes IFNγ/TNFα-induced muscle wasting in an NF-κB-dependent and IL-6-independent manner. EMBO Mol. Med. 2017, 9, 622–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artigas, N.; Ureña, C.; Rodríguez-Carballo, E.; Rosa, J.L.; Ventura, F. Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-regulated interactions between Osterix and Runx2 are critical for the transcriptional osteogenic program. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 27105–27117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, I.; Kouzmenko, A.P.; Kato, S. Wnt and PPARγ signaling in osteoblastogenesis and adipogenesis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2009, 5, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Zhao, Z.; Yi, J. Osteogenesis of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell in hyperglycemia. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1150068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, S.; Wong, S.K.; Mohamad, N.V.; Chin, K.Y. A review of the relationship between insulin and bone health. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanazawa, I. Osteocalcin as a hormone regulating glucose metabolism. World J. Diabetes 2015, 6, 1345–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faienza, M.F.; Luce, V.; Ventura, A.; Colaianni, G.; Colucci, S.; Cavallo, L.; Grano, M.; Brunetti, G. Skeleton and glucose metabolism: A bone-pancreas loop. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 2015, 758148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, G.; D’Amato, G.; De Santis, S.; Grano, M.; Faienza, M.F. Mechanisms of altered bone remodeling in children with type 1 diabetes. World J. Diabetes 2021, 12, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, B. Biomolecular basis of the role of diabetes mellitus in osteoporosis and bone fractures. World J. Diabetes 2013, 4, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, G. Recent updates on diabetes and bone. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dial, A.G.; Grafham, G.K.; Monaco, C.M.F.; Voth, J.; Brandt, L.; Tarnopolsky, M.A.; Hawke, T.J. Alterations in skeletal muscle repair in young adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2021, 321, C876–C883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dongare-Bhor, S.; Lohiya, N.; Maheshwari, A.; Ekbote, V.; Chiplonkar, S.; Padidela, R.; Mughal, Z.; Khadilkar, V.; Khadilkar, A. Muscle and bone parameters in underprivileged Indian children and adolescents with T1DM. Bone 2020, 130, 115074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maratova, K.; Soucek, O.; Matyskova, J.; Hlavka, Z.; Petruzelkova, L.; Obermannova, B.; Pruhova, S.; Kolouskova, S.; Sumnik, Z. Muscle functions and bone strength are impaired in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Bone 2018, 106, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Rostami Haji Abadi, M.; Ghafouri, Z.; Meira Goes, S.; Johnston, J.J.D.; Nour, M.; Kontulainen, S. Bone deficits in children and youth with type 1 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone 2022, 163, 116509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, J.O.B.; Jørgensen, N.R.; Pociot, F.; Johannesen, J. Bone turnover markers in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes—A systematic review. Pediatr. Diabetes 2019, 20, 510–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C.; Shepherd, S.; McMillan, M.; McNeilly, J.; Foster, J.; Wong, S.C.; Robertson, K.J.; Ahmed, S.F. Skeletal fragility and its clinical determinants in children with type 1 diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 104, 3585–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faienza, M.F.; Ventura, A.; Delvecchio, M.; Fusillo, A.; Piacente, L.; Aceto, G.; Colaianni, G.; Colucci, S.; Cavallo, L.; Grano, M.; et al. High sclerostin and Dickkopf-1 (DKK-1) serum levels in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 102, 1174–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thong, E.P.; Herath, M.; Weber, D.R.; Ranasinha, S.; Ebeling, P.R.; Milat, F.; Teede, H. Fracture risk in young and middle-aged adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Endocrinol. 2018, 89, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, D.R.; Haynes, K.; Leonard, M.B.; Willi, S.M.; Denburg, M.R. Type 1 diabetes is associated with an increased risk of fracture across the life span: A population-based cohort study using The Health Improvement Network (THIN). Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 1913–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bock, M.; Agwu, J.C.; Deabreu, M.; Dovc, K.; Maahs, D.M.; Marcovecchio, M.L.; Mahmud, F.H.; Nóvoa-Medina, Y.; Priyambada, L.; Smart, C.E.; et al. International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes clinical practice consensus guidelines 2024: Glycemic targets. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2024, 97, 546–554. [Google Scholar]

- Bombaci, B.; Passanisi, S.; Longo, A.; Aramnejad, S.; Rigano, F.; Marzà, M.C.; Formica, T.; Pecoraro, M.; Lombardo, F.; Salzano, G. The interplay between psychological well-being, diabetes-related distress, and glycemic control: A continuous glucose monitoring analysis from a population of adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J. Diabetes Its Complicat. 2025, 39, 109142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annan, S.F.; Higgins, L.A.; Jelleryd, E.; Hannon, T.; Rose, S.; Salis, S.; Baptista, J.; Chinchilla, P.; Marcovecchio, M.L. ISPAD clinical practice consensus guidelines 2022: Nutritional management in children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2022, 23, 1297–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chai, M.; Lin, M. Proportion of vitamin D deficiency in children/adolescents with type 1 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2024, 24, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demay, M.B.; Pittas, A.G.; Bikle, D.D.; Diab, D.L.; Kiely, M.E.; Lazaretti-Castro, M.; Lips, P.; Mitchell, D.M.; Murad, M.H.; Powers, S.; et al. Vitamin D for the prevention of disease: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 109, 1907–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faienza, M.F.; Brunetti, G.; Sanesi, L.; Colaianni, G.; Celi, M.; Piacente, L.; D’Amato, G.; Schipani, E.; Colucci, S.; Grano, M. High irisin levels are associated with better glycemic control and bone health in children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 141, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, J.Y.; Siopi, A.; Mougios, V.; Park, K.H.; Mantzoros, C.S. Irisin in response to exercise in humans with and without metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, E453–E457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, V.B.; Lim, R.; Teo, S.; Soon, W.H.K.; Roby, H.C.; Roberts, G.; Smith, G.J.; Fournier, P.A.; Jones, T.W.; Davis, E.A. A novel mobile health app to educate and empower young adults with type 1 diabetes to exercise safely: Prospective single-arm pre-post noninferiority clinical trial. JMIR Diabetes 2025, 10, e68694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vitale, R.; Linguiti, G.; Granberg, V.; Lattanzio, C.; Giordano, P.; Faienza, M.F. Muscle-Bone Crosstalk and Metabolic Dysregulation in Children and Young People Affected with Type 1 Diabetes: Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Cells 2025, 14, 1611. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14201611

Vitale R, Linguiti G, Granberg V, Lattanzio C, Giordano P, Faienza MF. Muscle-Bone Crosstalk and Metabolic Dysregulation in Children and Young People Affected with Type 1 Diabetes: Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Cells. 2025; 14(20):1611. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14201611

Chicago/Turabian StyleVitale, Rossella, Giovanna Linguiti, Vanja Granberg, Crescenza Lattanzio, Paola Giordano, and Maria Felicia Faienza. 2025. "Muscle-Bone Crosstalk and Metabolic Dysregulation in Children and Young People Affected with Type 1 Diabetes: Mechanisms and Clinical Implications" Cells 14, no. 20: 1611. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14201611

APA StyleVitale, R., Linguiti, G., Granberg, V., Lattanzio, C., Giordano, P., & Faienza, M. F. (2025). Muscle-Bone Crosstalk and Metabolic Dysregulation in Children and Young People Affected with Type 1 Diabetes: Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Cells, 14(20), 1611. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14201611