The Evolution of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation to Overcome Access Disparities: The Role of NMDP

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The History of NMDP

3. Mismatched Unrelated Donor Research to Improve Access and Outcomes

- Improving patient survival and quality of life by decreasing acute and long-term toxicities associated with standard dose PTCy;

- Decreasing relapse by enabling increased use of myeloablative conditioning in the MMUD setting;

4. Research and Advocacy to Create Meaningful Change for All Patients

- Increasing awareness among hematologists oncologists and patients;

- Reducing poverty-related barriers through patient, center, and policy initiatives;

- Improving access and outcomes regardless of race and ethnicity.

5. Future Direction

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Auletta, J.; Kou, J.; Chen, M.; Bolon, Y.; Broglie, L.; Bupp, C.; Christianson, D.; Cusatis, R.N.; Devine, S.M.; Eapen, M.; et al. Real-world data showing trends and outcomes by race and ethnicity in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: A report from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research. Transplant. Cell. Ther. 2023, 29, 346.e1–346.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullough, J.; Perkins, H.A.; Hansen, J. The National Marrow Donor Program with emphasis on the early years. Transfusion 2006, 46, 1248–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NMDP Finance Department. NMDP Fiscal Year 2023 Internal Data; NMDP Finance Department: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- WMDA. Total Number of Donors and Cord Blood Units. Last Modified 29 March 2024. Available online: https://statistics.wmda.info/ (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Confer, D.; Robinett, P. The US National Marrow Donor Program role in unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008, 42 (Suppl. S1), S3–S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NMDP National Marrow Donor Program. Be the Match Forms New Cellular Therapies Subsidiary. Published 22 January 2016. Available online: https://bethematch.org/news/news-releases/national-marrow-donor-program-be-the-match-forms-new-cellular-therapies-subsidiary/ (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- NMDP. Be the Match® Affirms Global Leadership in Life-Saving Cell Therapies with New Name, Brand: NMDP. Published 8 January 2024. Available online: https://bethematch.org/news/news-releases/be-the-match--affirms-global-leadership-in-life-saving-cell-therapies-with-new-name--brand---nmdp/ (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Lee, S.J.; Klein, J.; Haagenson, M.; Baxter-Lowe, L.A.; Confer, D.L.; Eapen, M.; Fernandez-Vina, M.; Flomenberg, N.; Horowitz, M.; Hurley, C.K.; et al. High-resolution donor-recipient HLA matching contributes to the success of unrelated donor marrow transplantation. Blood 2007, 110, 4576–4583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

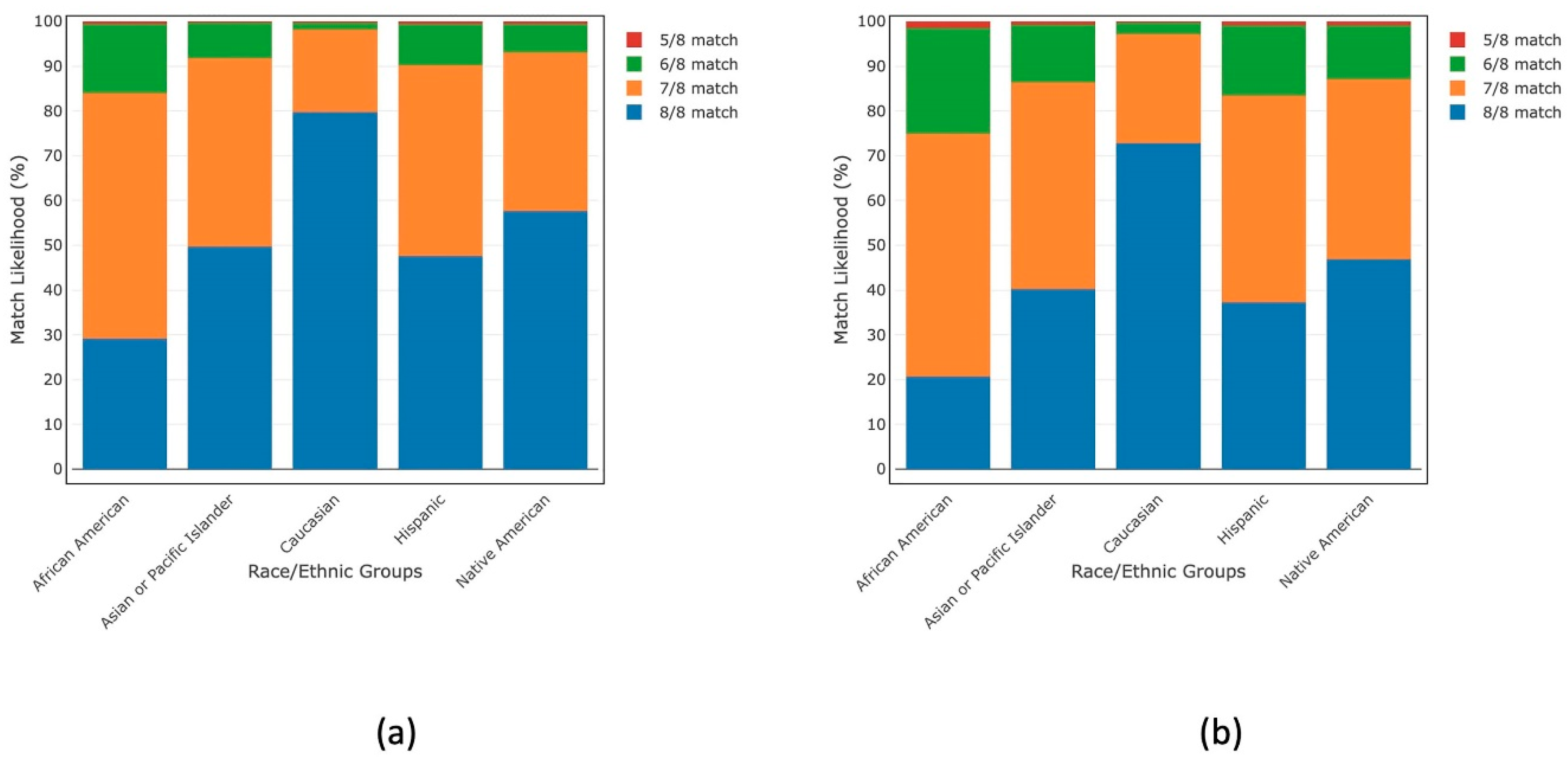

- Gragert, L.; Eapen, M.; Williams, E.; Freeman, J.; Spellman, S.; Baitty, R.; Hartzman, R.; Rizzo, J.D.; Horowitz, M.; Confer, D.; et al. HLA match likelihoods for hematopoietic stem-cell grafts in the U.S. registry. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, A.S.; Maiers, M.; Spellman, S.R.; Deshpande, T.; Bolon, Y.T.; Devine, S.M. Existence of HLA-mismatched unrelated donors closes the gap in donor availability regardless of recipient ancestry. Transplant. Cell. Ther. 2023, 29, 686.e1–686.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gragert, L.; Madbouly, A.; Freeman, J.; Maiers, M. Six-locus high resolution HLA haplotype frequencies derived from mixed-resolution DNA typing for the entire US donor registry. Hum. Immunol. 2013, 74, 1313–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiers, M. (NMDP, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Personal communication. October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Luznik, L.; O’Donnell, P.V.; Symons, H.J.; Chen, A.R.; Leffell, M.S.; Zahurak, M.; Gooley, T.A.; Piantadosi, S.; Kaup, M.; Ambinder, R.F.; et al. HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation for hematologic malignancies using nonmyeloablative conditioning and high-dose, posttransplantation cyclophosphamide. Biol. Blood Marrow. Transplant. 2008, 14, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auletta, J.J.; Al Malki, M.M.; DeFor, T.; Shaffer, B.C.; Gooptu, M.; Bolanos-Meade, J.; Abboud, R.; Briggs, A.D.; Khimani, F.; Modi, D.; et al. Post-transplant cyclophosphamide eliminates disparity in GvHD-free, relapse-free survival and overall survival between 8/8 matched and 7/8 mismatched unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation in adults with hematologic malignancies. Blood 2023, 143 (Suppl. S1), 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, B.E.; Jimenez-Jimenez, A.M.; Burns, L.J.; Logan, B.R.; Khimani, F.; Shaffer, B.C.; Shah, N.N.; Mussetter, A.; Tang, X.; McCarty, J.M.; et al. National Marrow Donor Program-sponsored multicenter, phase II trial of HLA-mismatched unrelated donor bone marrow transplantation using post-transplant cyclophosphamide. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 1971–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, B.E.; Jimenez-Jimenez, A.M.; Burns, L.J.; Logan, B.R.; Khimani, F.; Shaffer, B.C.; Shah, N.N.; Mussetter, A.; Tang, X.; McCarty, J.M.; et al. Three-year outcomes in recipients of mismatched unrelated bone marrow donor transplants using post-transplantation cyclophosphamide: Follow-up from a National Marrow Donor Program-sponsored prospective clinical trial. Transplant. Cell. Ther. 2023, 29, 208.e1–208.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins, B.; Qayed, M.; McCracken, C.; Bratrude, B.; Betz, K.; Suessmuth, Y.; Yu, A.; Sinclair, S.; Furlan, S.; Bosinger, S.; et al. Phase II trial of costimulation blockade with abatacept for prevention of acute GVHD. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 1865–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kean, L.S.; Burns, L.J.; Kou, T.D.; Kapikian, R.; Tang, X.; Zhang, M.; Hemmer, M.; Connolly, S.E.; Polinsky, M.; Gavin, B.; et al. Improved overall survival of patients treated with abatacept in combination with a calcineurin inhibitor and methotrexate following 7/8 HLA-matched unrelated allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: Analysis of the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant research database. Blood 2021, 138 (Suppl. S1), 3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayed, M.; Watkins, B.; Gillespie, S.; Bratrude, B.; Betz, K.; Choi, S.W.; Davis, J.; Duncan, C.; Giller, R.; Grimley, M.; et al. Abatacept for GVHD prophylaxis can reduce racial disparities by abrogating the impact of mismatching in unrelated donor stem cell transplantation. Blood Adv. 2022, 6, 746–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. HLA-Mismatched Unrelated Donor Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation with Post-Transplantation Cyclophosphamide (ACCESS). Last Updated 21 February 2024. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04904588 (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. HLA-Mismatched Unrelated Donor Peripheral Blood Stem Cell Transplantation with Reduced Dose Post Transplantation Cyclophosphamide GvHD Prophylaxis (OPTIMIZE). Last Updated 13 March 2024. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06001385?term=NCT06001385&rank=1 (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Bolaños-Meade, J.; Hamadani, M.; Wu, J.; Al Malki, M.M.; Martens, M.J.; Runaas, L.; Elmariah, H.; Rezvani, A.R.; Gooptu, M.; Larkin, K.T.; et al. Post-transplantation cyclophosphamide-based graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 2338–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BioSpace. NMDP Announces Enrollment of First Patient in OPTIMIZE Clinical Trial Groundbreaking Trial Seeks to Enhance Blood Cancer Treatment Efficacy and Safety. Published 20 February 2024. Available online: https://www.biospace.com/article/releases/nmdp-announces-enrollment-of-first-patient-in-optimize-clinical-trialgroundbreaking-trial-seeks-to-enhance-blood-cancer-treatment-efficacy-and-safety/ (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data & Statistics on Sickle Cell Disease. Last Reviewed on 6 July 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/sickle-cell/data/index.html (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Sparapani, R.A.; Maiers, M.J.; Spellman, S.R.; Shaw, B.E.; Laud, P.W.; Devine, S.M.; Bupp, C.; He, M.; Logan, B.R. Is the youngest donor always the best choice to optimize outcomes for matched unrelated allogeneic transplant? Improving precision using novel statistical methodology. Blood 2023, 142 (Suppl. S1), 3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, B.R.; Maiers, M.J.; Sparapani, R.A.; Laud, P.W.; Spellman, S.R.; McCulloch, R.E.; Shaw, B.E. Optimal donor selection for hematopoietic cell transplantation using Bayesian Machine Learning. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2021, 5, 494–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NMDP. The Life Saving Leave Act. Available online: https://bethematch.org/support-the-cause/get-involved/join-our-legislative-advocacy-efforts/donor-leave/ (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- The Hill. Congress Must Act Following Cancer Research Breakthrough. Published 28 February 2024. Available online: https://thehill.com/opinion/4494538-congress-must-act-following-cancer-research-breakthrough/ (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Auletta, J.J.; Sandmaier, B.M.; Jensen, E.; Majhail, N.S.; Knutson, J.; Nemeck, E.; Ajayi-Hackworth, F.; Davies, S.M.; ACCESS Workshop Team. The ASTCT-NMDP ACCESS Initiative: A collaboration to address and sustain equal outcomes for all across the hematopoietic cell transplantation and cellular therapy ecosystem. Transplant. Cell. Ther. 2022, 28, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Devine, S.M. The Evolution of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation to Overcome Access Disparities: The Role of NMDP. Cells 2024, 13, 933. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13110933

Devine SM. The Evolution of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation to Overcome Access Disparities: The Role of NMDP. Cells. 2024; 13(11):933. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13110933

Chicago/Turabian StyleDevine, Steven M. 2024. "The Evolution of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation to Overcome Access Disparities: The Role of NMDP" Cells 13, no. 11: 933. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13110933

APA StyleDevine, S. M. (2024). The Evolution of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation to Overcome Access Disparities: The Role of NMDP. Cells, 13(11), 933. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13110933