Aurora A and AKT Kinase Signaling Associated with Primary Cilia

Abstract

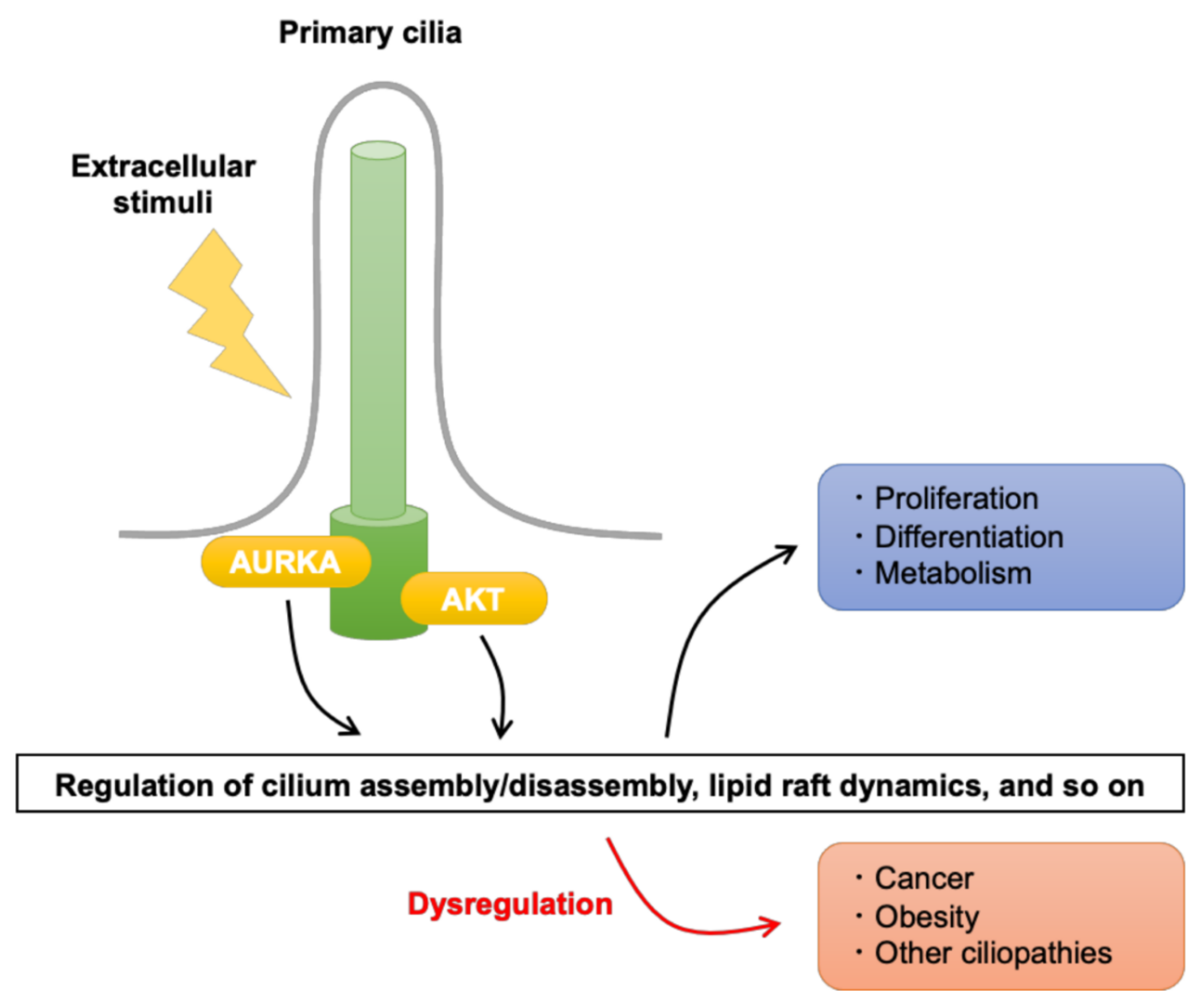

:1. Introduction

2. Aurora Kinase a Signaling and Its Regulation in Primary Cilia

2.1. TCHP

2.2. NEDD9

2.3. CEP55

3. AKT Signaling and Its Regulation in Primary Cilia

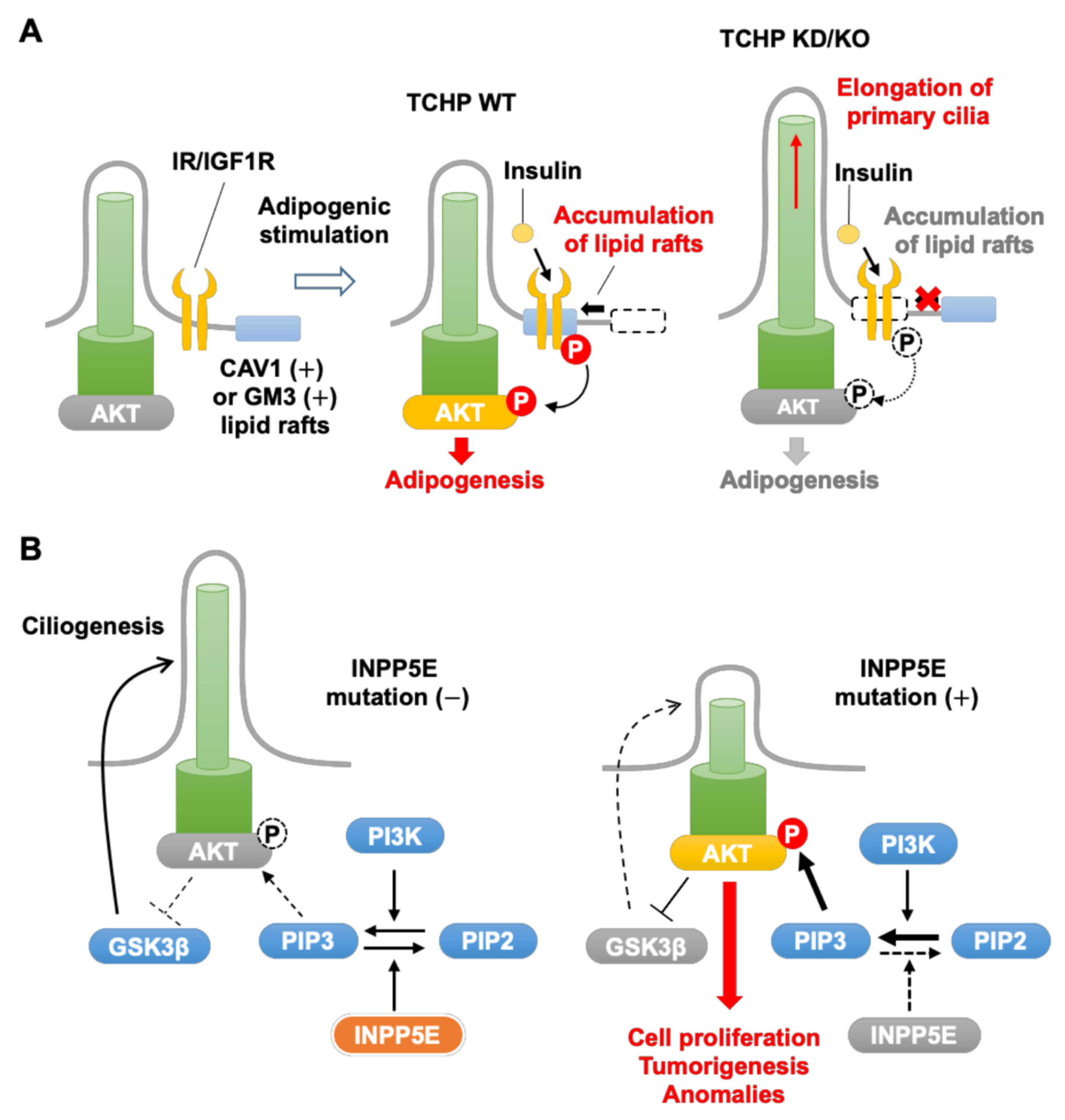

3.1. TCHP

3.2. INPP5E

3.3. VHL

4. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fabbro, D.; Cowan-Jacob, S.W.; Moebitz, H. Ten things you should know about protein kinases: IUPHAR Review 14. Br. J. Pharm. 2015, 172, 2675–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cohen, P. The role of protein phosphorylation in human health and disease. The Sir Hans Krebs Medal Lecture. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001, 268, 5001–5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iakoucheva, L.M.; Radivojac, P.; Brown, C.J.; O’Connor, T.R.; Sikes, J.G.; Obradovic, Z.; Dunker, A.K. The importance of intrinsic disorder for protein phosphorylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 1037–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kung, J.E.; Jura, N. Structural Basis for the Non-catalytic Functions of Protein Kinases. Structure 2016, 24, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Adhikari, B.; Bozilovic, J.; Diebold, M.; Schwarz, J.D.; Hofstetter, J.; Schröder, M.; Wanior, M.; Narain, A.; Vogt, M.; Dudvarski Stankovic, N.; et al. PROTAC-mediated degradation reveals a non-catalytic function of AURORA-A kinase. Nat. Chem. Biol 2020, 16, 1179–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazaro, G.; Kostaras, E.; Vivanco, I. Inhibitors in AKTion: ATP-competitive vs allosteric. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2020, 48, 933–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willems, E.; Dedobbeleer, M.; Digregorio, M.; Lombard, A.; Lumapat, P.N.; Rogister, B. The functional diversity of Aurora kinases: A comprehensive review. Cell Div. 2018, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kostaras, E.; Kaserer, T.; Lazaro, G.; Heuss, S.F.; Hussain, A.; Casado, P.; Hayes, A.; Yandim, C.; Palaskas, N.; Yu, Y.; et al. A systematic molecular and pharmacologic evaluation of AKT inhibitors reveals new insight into their biological activity. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 123, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruff, E.F.; Muretta, J.M.; Thompson, A.R.; Lake, E.W.; Cyphers, S.; Albanese, S.K.; Hanson, S.M.; Behr, J.M.; Thomas, D.D.; Chodera, J.D.; et al. A dynamic mechanism for allosteric activation of Aurora kinase A by activation loop phosphorylation. eLife 2018, 7, e32766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hammond, D.; Zeng, K.; Espert, A.; Bastos, R.N.; Baron, R.D.; Gruneberg, U.; Barr, F.A. Melanoma-associated mutations in protein phosphatase 6 cause chromosome instability and DNA damage owing to dysregulated Aurora-A. J. Cell Sci. 2013, 126, 3429–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Janeček, M.; Rossmann, M.; Sharma, P.; Emery, A.; Huggins, D.J.; Stockwell, S.R.; Stokes, J.E.; Tan, Y.S.; Almeida, E.G.; Hardwick, B.; et al. Allosteric modulation of AURKA kinase activity by a small-molecule inhibitor of its protein-protein interaction with TPX2. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bayliss, R.; Burgess, S.G.; McIntyre, P.J. Switching Aurora-A kinase on and off at an allosteric site. FEBS J. 2017, 284, 2947–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Levinson, N.M. The multifaceted allosteric regulation of Aurora kinase A. Biochem. J. 2018, 475, 2025–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lake, E.W.; Muretta, J.M.; Thompson, A.R.; Rasmussen, D.M.; Majumdar, A.; Faber, E.B.; Ruff, E.F.; Thomas, D.D.; Levinson, N.M. Quantitative conformational profiling of kinase inhibitors reveals origins of selectivity for Aurora kinase activation states. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E11894–E11903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Otto, T.; Horn, S.; Brockmann, M.; Eilers, U.; Schüttrumpf, L.; Popov, N.; Kenney, A.M.; Schulte, J.H.; Beijersbergen, R.; Christiansen, H.; et al. Stabilization of N-Myc is a critical function of Aurora A in human neuroblastoma. Cancer Cell 2009, 15, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brodeur, G.M.; Seeger, R.C.; Schwab, M.; Varmus, H.E.; Bishop, J.M. Amplification of N-myc in untreated human neuroblastomas correlates with advanced disease stage. Science 1984, 224, 1121–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K.; Phillips, J.W.; Smith, B.A.; Park, J.W.; Stoyanova, T.; McCaffrey, E.F.; Baertsch, R.; Sokolov, A.; Meyerowitz, J.G.; Mathis, C.; et al. N-Myc Drives Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer Initiated from Human Prostate Epithelial Cells. Cancer Cell 2016, 29, 536–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brockmann, M.; Poon, E.; Berry, T.; Carstensen, A.; Deubzer, H.E.; Rycak, L.; Jamin, Y.; Thway, K.; Robinson, S.P.; Roels, F.; et al. Small molecule inhibitors of aurora-a induce proteasomal degradation of N-myc in childhood neuroblastoma. Cancer Cell 2013, 24, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gustafson, W.C.; Meyerowitz, J.G.; Nekritz, E.A.; Chen, J.; Benes, C.; Charron, E.; Simonds, E.F.; Seeger, R.; Matthay, K.K.; Hertz, N.T.; et al. Drugging MYCN through an allosteric transition in Aurora kinase A. Cancer Cell 2014, 26, 414–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lučić, I.; Rathinaswamy, M.K.; Truebestein, L.; Hamelin, D.J.; Burke, J.E.; Leonard, T.A. Conformational sampling of membranes by Akt controls its activation and inactivation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E3940–E3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sugiyama, M.G.; Fairn, G.D.; Antonescu, C.N. Akt-ing Up Just About Everywhere: Compartment-Specific Akt Activation and Function in Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Signaling. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korobeynikov, V.; Deneka, A.Y.; Golemis, E.A. Mechanisms for nonmitotic activation of Aurora-A at cilia. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2017, 45, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bertolin, G.; Tramier, M. Insights into the non-mitotic functions of Aurora kinase A: More than just cell division. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2020, 77, 1031–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berndt, N.; Karim, R.M.; Schönbrunn, E. Advances of small molecule targeting of kinases. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2017, 39, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida Magalhães, T.; de Sousa, G.R.; Alencastro Veiga Cruzeiro, G.; Tone, L.G.; Valera, E.T.; Borges, K.S. The therapeutic potential of Aurora kinases targeting in glioblastoma: From preclinical research to translational oncology. J. Mol. Med. 2020, 98, 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martorana, F.; Motta, G.; Pavone, G.; Motta, L.; Stella, S.; Vitale, S.R.; Manzella, L.; Vigneri, P. AKT Inhibitors: New Weapons in the Fight Against Breast Cancer? Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 662232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslanhan, M.D.; Rauniyar, N.; Yates, J.R., III; Firat-Karalar, E.N. Aurora Kinase A proximity map reveals centriolar satellites as regulators of its ciliary function. EMBO Rep. 2021, 22, e51902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anvarian, Z.; Mykytyn, K.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Pedersen, L.B.; Christensen, S.T. Cellular signalling by primary cilia in development, organ function and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2019, 15, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malicki, J.J.; Johnson, C.A. The Cilium: Cellular Antenna and Central Processing Unit. Trends Cell Biol. 2017, 27, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goto, H.; Inoko, A.; Inagaki, M. Cell cycle progression by the repression of primary cilia formation in proliferating cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013, 70, 3893–3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Izawa, I.; Goto, H.; Kasahara, K.; Inagaki, M. Current topics of functional links between primary cilia and cell cycle. Cilia 2015, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goto, H.; Inaba, H.; Inagaki, M. Mechanisms of ciliogenesis suppression in dividing cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nishimura, Y.; Kasahara, K.; Shiromizu, T.; Watanabe, M.; Inagaki, M. Primary cilia as signaling hubs in health and disease. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1801138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kasahara, K.; Inagaki, M. Primary ciliary signaling: Links with the cell cycle. Trends Cell Biol. 2021, 31, 954–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, G.; Raleigh, D.R.; Reiter, J.F. How the Ciliary Membrane Is Organized Inside-Out to Communicate Outside-In. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, R421–R434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, K.H.; Brugmann, S.A. Sending mixed signals: Cilia-dependent signaling during development and disease. Dev. Biol. 2018, 447, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Dynlacht, B.D. The regulation of cilium assembly and disassembly in development and disease. Development 2018, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nishimura, Y.; Kasahara, K.; Inagaki, M. Intermediate filaments and IF-associated proteins: From cell architecture to cell proliferation. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2019, 95, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bernabé-Rubio, M.; Alonso, M.A. Routes and machinery of primary cilium biogenesis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 4077–4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirvis, M.; Stearns, T.; James Nelson, W. Cilium structure, assembly, and disassembly regulated by the cytoskeleton. Biochem. J. 2018, 475, 2329–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hossain, D.; Tsang, W.Y. The role of ubiquitination in the regulation of primary cilia assembly and disassembly. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 93, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Liang, Z.; Liu, P. Functional aspects of primary cilium in signaling, assembly and microenvironment in cancer. J. Cell. Physiol. 2021, 236, 3207–3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, R.W.; Pardee, A.B.; Fujiwara, K. Centriole ciliation is related to quiescence and DNA synthesis in 3T3 cells. Cell 1979, 17, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, R.W.; Scher, C.D.; Stiles, C.D. Centriole deciliation associated with the early response of 3T3 cells to growth factors but not to SV40. Cell 1979, 18, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieder, C.L.; Jensen, C.G.; Jensen, L.C.W. The resorption of primary cilia during mitosis in a vertebrate (PtK1) cell line. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 1979, 68, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugacheva, E.N.; Jablonski, S.A.; Hartman, T.R.; Henske, E.P.; Golemis, E.A. HEF1-dependent Aurora A activation induces disassembly of the primary cilium. Cell 2007, 129, 1351–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Inoko, A.; Matsuyama, M.; Goto, H.; Ohmuro-Matsuyama, Y.; Hayashi, Y.; Enomoto, M.; Ibi, M.; Urano, T.; Yonemura, S.; Kiyono, T.; et al. Trichoplein and Aurora A block aberrant primary cilia assembly in proliferating cells. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 197, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kasahara, K.; Kawakami, Y.; Kiyono, T.; Yonemura, S.; Kawamura, Y.; Era, S.; Matsuzaki, F.; Goshima, N.; Inagaki, M. Ubiquitin-proteasome system controls ciliogenesis at the initial step of axoneme extension. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Inaba, H.; Goto, H.; Kasahara, K.; Kumamoto, K.; Yonemura, S.; Inoko, A.; Yamano, S.; Wanibuchi, H.; He, D.; Goshima, N.; et al. Ndel1 suppresses ciliogenesis in proliferating cells by regulating the trichoplein-Aurora A pathway. J. Cell Biol. 2016, 212, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kasahara, K.; Aoki, H.; Kiyono, T.; Wang, S.; Kagiwada, H.; Yuge, M.; Tanaka, T.; Nishimura, Y.; Mizoguchi, A.; Goshima, N.; et al. EGF receptor kinase suppresses ciliogenesis through activation of USP8 deubiquitinase. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Urdiciain, A.; Erausquin, E.; Meléndez, B.; Rey, J.A.; Idoate, M.A.; Castresana, J.S. Tubastatin A, an inhibitor of HDAC6, enhances temozolomide—induced apoptosis and reverses the malignant phenotype of glioblastoma cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2019, 54, 1797–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Li, J.; Yang, X.; Ma, J.; Gong, F.; Liu, Y. Prdx1 promotes the loss of primary cilia in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, C.; Papon, L.; Cacheux, W.; Marques Sousa, P.; Lascano, V.; Tort, O.; Giordano, T.; Vacher, S.; Lemmers, B.; Mariani, P.; et al. Tubulin glycylases are required for primary cilia, control of cell proliferation and tumor development in colon. EMBO J. 2014, 33, 2247–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gradilone, S.A.; Radtke, B.N.; Bogert, P.S.; Huang, B.Q.; Gajdos, G.B.; LaRusso, N.F. HDAC6 inhibition restores ciliary expression and decreases tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 2259–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mansini, A.P.; Peixoto, E.; Thelen, K.M.; Gaspari, C.; Jin, S.; Gradilone, S.A. The cholangiocyte primary cilium in health and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2018, 1864, 1245–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeley, E.S.; Carriere, C.; Goetze, T.; Longnecker, D.S.; Korc, M. Pancreatic cancer and precursor pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia lesions are devoid of primary cilia. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kobayashi, T.; Nakazono, K.; Tokuda, M.; Mashima, Y.; Dynlacht, B.D.; Itoh, H. HDAC2 promotes loss of primary cilia in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. EMBO Rep. 2017, 18, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Esteban, M.A.; Harten, S.K.; Tran, M.G.; Maxwell, P.H. Formation of primary cilia in the renal epithelium is regulated by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 17, 1801–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schraml, P.; Frew, I.J.; Thoma, C.R.; Boysen, G.; Struckmann, K.; Krek, W.; Moch, H. Sporadic clear cell renal cell carcinoma but not the papillary type is characterized by severely reduced frequency of primary cilia. Mod. Pathol 2009, 22, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Basten, S.G.; Willekers, S.; Vermaat, J.S.; Slaats, G.G.; Voest, E.E.; van Diest, P.J.; Giles, R.H. Reduced cilia frequencies in human renal cell carcinomas versus neighboring parenchymal tissue. Cilia 2013, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dere, R.; Perkins, A.L.; Bawa-Khalfe, T.; Jonasch, D.; Walker, C.L. beta-catenin links von Hippel-Lindau to aurora kinase A and loss of primary cilia in renal cell carcinoma. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 26, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhattacharya, R.; Kwon, J.; Ali, B.; Wang, E.; Patra, S.; Shridhar, V.; Mukherjee, P. Role of hedgehog signaling in ovarian cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 7659–7666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Egeberg, D.L.; Lethan, M.; Manguso, R.; Schneider, L.; Awan, A.; Jorgensen, T.S.; Byskov, A.G.; Pedersen, L.B.; Christensen, S.T. Primary cilia and aberrant cell signaling in epithelial ovarian cancer. Cilia 2012, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yuan, K.; Frolova, N.; Xie, Y.; Wang, D.; Cook, L.; Kwon, Y.J.; Steg, A.D.; Serra, R.; Frost, A.R. Primary cilia are decreased in breast cancer: Analysis of a collection of human breast cancer cell lines and tissues. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2010, 58, 857–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hassounah, N.B.; Nagle, R.; Saboda, K.; Roe, D.J.; Dalkin, B.L.; McDermott, K.M. Primary cilia are lost in preinvasive and invasive prostate cancer. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qie, Y.; Wang, L.; Du, E.; Chen, S.; Lu, C.; Ding, N.; Yang, K.; Xu, Y. TACC3 promotes prostate cancer cell proliferation and restrains primary cilium formation. Exp. Cell Res. 2020, 390, 111952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Dabiri, S.; Seeley, E.S. Primary cilium depletion typifies cutaneous melanoma in situ and malignant melanoma. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zingg, D.; Debbache, J.; Peña-Hernández, R.; Antunes, A.T.; Schaefer, S.M.; Cheng, P.F.; Zimmerli, D.; Haeusel, J.; Calçada, R.R.; Tuncer, E.; et al. EZH2-Mediated Primary Cilium Deconstruction Drives Metastatic Melanoma Formation. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.; Ali, S.A.; Al-Jazrawe, M.; Kandel, R.; Wunder, J.S.; Alman, B.A. Primary cilia attenuate hedgehog signalling in neoplastic chondrocytes. Oncogene 2013, 32, 5388–5396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiang, W.; Guo, F.; Cheng, W.; Zhang, J.; Huang, J.; Wang, R.; Ma, Z.; Xu, K. HDAC6 inhibition suppresses chondrosarcoma by restoring the expression of primary cilia. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 38, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, H.; Kiseleva, A.A.; Golemis, E.A. Ciliary signalling in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, L.; Bost, F.; Mazure, N.M. Primary Cilium in Cancer Hallmarks. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Higgins, M.; Obaidi, I.; McMorrow, T. Primary cilia and their role in cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 17, 3041–3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiromizu, T.; Yuge, M.; Kasahara, K.; Yamakawa, D.; Matsui, T.; Bessho, Y.; Inagaki, M.; Nishimura, Y. Targeting E3 Ubiquitin Ligases and Deubiquitinases in Ciliopathy and Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, E.; Richard, S.; Pant, K.; Biswas, A.; Gradilone, S.A. The primary cilium: Its role as a tumor suppressor organelle. Biochem. Pharm. 2020, 175, 113906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halder, P.; Khatun, S.; Majumder, S. Freeing the brake: Proliferation needs primary cilium to disassemble. J. Biosci. 2020, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariman, E.C.; Vink, R.G.; Roumans, N.J.; Bouwman, F.G.; Stumpel, C.T.; Aller, E.E.; van Baak, M.A.; Wang, P. The cilium: A cellular antenna with an influence on obesity risk. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 116, 576–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hilgendorf, K.I.; Johnson, C.T.; Mezger, A.; Rice, S.L.; Norris, A.M.; Demeter, J.; Greenleaf, W.J.; Reiter, J.F.; Kopinke, D.; Jackson, P.K. Omega-3 Fatty Acids Activate Ciliary FFAR4 to Control Adipogenesis. Cell 2019, 179, 1289–1305.e1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamakawa, D.; Katoh, D.; Kasahara, K.; Shiromizu, T.; Matsuyama, M.; Matsuda, C.; Maeno, Y.; Watanabe, M.; Nishimura, Y.; Inagaki, M. Primary cilia-dependent lipid raft/caveolin dynamics regulate adipogenesis. Cell Rep. 2021, 34, 108817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.M.; Kang, G.M.; Byun, K.; Ko, H.W.; Kim, J.; Shin, M.S.; Kim, H.K.; Gil, S.Y.; Yu, J.H.; Lee, B.; et al. Leptin-promoted cilia assembly is critical for normal energy balance. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 2193–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ernst, M.B.; Wunderlich, C.M.; Hess, S.; Paehler, M.; Mesaros, A.; Koralov, S.B.; Kleinridders, A.; Husch, A.; Munzberg, H.; Hampel, B.; et al. Enhanced Stat3 activation in POMC neurons provokes negative feedback inhibition of leptin and insulin signaling in obesity. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 11582–11593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mesaros, A.; Koralov, S.B.; Rother, E.; Wunderlich, F.T.; Ernst, M.B.; Barsh, G.S.; Rajewsky, K.; Bruning, J.C. Activation of Stat3 signaling in AgRP neurons promotes locomotor activity. Cell Metab. 2008, 7, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Davenport, J.R.; Watts, A.J.; Roper, V.C.; Croyle, M.J.; van Groen, T.; Wyss, J.M.; Nagy, T.R.; Kesterson, R.A.; Yoder, B.K. Disruption of intraflagellar transport in adult mice leads to obesity and slow-onset cystic kidney disease. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, 1586–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oh, E.C.; Vasanth, S.; Katsanis, N. Metabolic regulation and energy homeostasis through the primary Cilium. Cell Metab. 2015, 21, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siljee, J.E.; Wang, Y.; Bernard, A.A.; Ersoy, B.A.; Zhang, S.; Marley, A.; Von Zastrow, M.; Reiter, J.F.; Vaisse, C. Subcellular localization of MC4R with ADCY3 at neuronal primary cilia underlies a common pathway for genetic predisposition to obesity. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grarup, N.; Moltke, I.; Andersen, M.K.; Dalby, M.; Vitting-Seerup, K.; Kern, T.; Mahendran, Y.; Jorsboe, E.; Larsen, C.V.L.; Dahl-Petersen, I.K.; et al. Loss-of-function variants in ADCY3 increase risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 172–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S.; Bonnefond, A.; Tamanini, F.; Mirza, M.U.; Manzoor, J.; Janjua, Q.M.; Din, S.M.; Gaitan, J.; Milochau, A.; Durand, E.; et al. Loss-of-function mutations in ADCY3 cause monogenic severe obesity. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loos, R.J.; Lindgren, C.M.; Li, S.; Wheeler, E.; Zhao, J.H.; Prokopenko, I.; Inouye, M.; Freathy, R.M.; Attwood, A.P.; Beckmann, J.S.; et al. Common variants near MC4R are associated with fat mass, weight and risk of obesity. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 768–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sebo, Z.L.; Rodeheffer, M.S. Assembling the adipose organ: Adipocyte lineage segregation and adipogenesis in vivo. Development 2019, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marion, V.; Stoetzel, C.; Schlicht, D.; Messaddeq, N.; Koch, M.; Flori, E.; Danse, J.M.; Mandel, J.L.; Dollfus, H. Transient ciliogenesis involving Bardet-Biedl syndrome proteins is a fundamental characteristic of adipogenic differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 1820–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marion, V.; Mockel, A.; De Melo, C.; Obringer, C.; Claussmann, A.; Simon, A.; Messaddeq, N.; Durand, M.; Dupuis, L.; Loeffler, J.P.; et al. BBS-induced ciliary defect enhances adipogenesis, causing paradoxical higher-insulin sensitivity, glucose usage, and decreased inflammatory response. Cell Metab. 2012, 16, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Conduit, S.E.; Vanhaesebroeck, B. Phosphoinositide lipids in primary cilia biology. Biochem. J. 2020, 477, 3541–3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenks, A.D.; Vyse, S.; Wong, J.P.; Kostaras, E.; Keller, D.; Burgoyne, T.; Shoemark, A.; Tsalikis, A.; de la Roche, M.; Michaelis, M.; et al. Primary Cilia Mediate Diverse Kinase Inhibitor Resistance Mechanisms in Cancer. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 3042–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, A.; Kreis, N.N.; Roth, S.; Friemel, A.; Jennewein, L.; Eichbaum, C.; Solbach, C.; Louwen, F.; Yuan, J. Restoration of primary cilia in obese adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells by inhibiting Aurora A or extracellular signal-regulated kinase. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmena, M.; Earnshaw, W.C.; Glover, D.M. The Dawn of Aurora Kinase Research: From Fly Genetics to the Clinic. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Otto, T.; Sicinski, P. Cell cycle proteins as promising targets in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nikonova, A.S.; Astsaturov, I.; Serebriiskii, I.G.; Dunbrack, R.L.J.; Golemis, E.A. Aurora A kinase (AURKA) in normal and pathological cell division. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2013, 70, 661–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardin, B.R.; Schiebel, E. Breaking the ties that bind: New advances in centrosome biology. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 197, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mardin, B.R.; Agircan, F.G.; Lange, C.; Schiebel, E. Plk1 controls the Nek2A-PP1γ antagonism in centrosome disjunction. Curr. Biol. 2011, 21, 1145–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hutterer, A.; Berdnik, D.; Wirtz-Peitz, F.; Zigman, M.; Schleiffer, A.; Knoblich, J.A. Mitotic activation of the kinase Aurora-A requires its binding partner Bora. Dev. Cell 2006, 11, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hirota, T.; Kunitoku, N.; Sasayama, T.; Marumoto, T.; Zhang, D.; Nitta, M.; Hatakeyama, K.; Saya, H. Aurora-A and an Interacting Activator, the LIM Protein Ajuba, Are Required for Mitotic Commitment in Human Cells. Cell 2003, 114, 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giubettini, M.; Asteriti, I.A.; Scrofani, J.; De Luca, M.; Lindon, C.; Lavia, P.; Guarguaglini, G. Control of Aurora-A stability through interaction with TPX2. J. Cell Sci. 2011, 124, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsai, M.-Y.; Zheng, Y. Aurora A Kinase-Coated Beads Function as Microtubule-Organizing Centers and Enhance RanGTP-Induced Spindle Assembly. Curr. Biol. 2005, 15, 2156–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sasai, K.; Parant, J.M.; Brandt, M.E.; Carter, J.; Adams, H.P.; Stass, S.A.; Killary, A.M.; Katayama, H.; Sen, S. Targeted disruption of Aurora A causes abnormal mitotic spindle assembly, chromosome misalignment and embryonic lethality. Oncogene 2008, 27, 4122–4127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Plotnikova, O.V.; Nikonova, A.S.; Loskutov, Y.V.; Kozyulina, P.Y.; Pugacheva, E.N.; Golemis, E.A. Calmodulin activation of Aurora-A kinase (AURKA) is required during ciliary disassembly and in mitosis. Mol. Biol. Cell 2012, 23, 2658–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; Johmura, Y.; Yu, L.R.; Park, J.E.; Gao, Y.; Bang, J.K.; Zhou, M.; Veenstra, T.D.; Yeon Kim, B.; Lee, K.S. Identification of a novel Wnt5a-CK1varepsilon-Dvl2-Plk1-mediated primary cilia disassembly pathway. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 3104–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhu, J.; Firozi, P.F.; Abbruzzese, J.L.; Evans, D.B.; Cleary, K.; Friess, H.; Sen, S. Overexpression of oncogenic STK15/BTAK/Aurora A kinase in human pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003, 9, 991–997. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Duncan, C.G.; Killela, P.J.; Payne, C.A.; Lampson, B.; Chen, W.C.; Liu, J.; Solomon, D.; Waldman, T.; Towers, A.J.; Gregory, S.G.; et al. Integrated genomic analyses identify ERRFI1 and TACC3 as glioblastoma-targeted genes. Oncotarget 2010, 1, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-Satta, M.; Matheu, A. Primary cilium and glioblastoma. Adv. Med. Oncol 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishizawa, M.; Izawa, I.; Inoko, A.; Hayashi, Y.; Nagata, K.; Yokoyama, T.; Usukura, J.; Inagaki, M. Identification of trichoplein, a novel keratin filament-binding protein. J. Cell Sci. 2005, 118, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ibi, M.; Zou, P.; Inoko, A.; Shiromizu, T.; Matsuyama, M.; Hayashi, Y.; Enomoto, M.; Mori, D.; Hirotsune, S.; Kiyono, T.; et al. Trichoplein controls microtubule anchoring at the centrosome by binding to Odf2 and ninein. J. Cell Sci. 2011, 124, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhou, M.H.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, Z.G. Intraflagellar transport 20: New target for the treatment of ciliopathies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2020, 1867, 118641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinzel, D.; Boldt, K.; Davis, E.E.; Burtscher, I.; Trümbach, D.; Diplas, B.; Attié-Bitach, T.; Wurst, W.; Katsanis, N.; Ueffing, M.; et al. Pitchfork regulates primary cilia disassembly and left-right asymmetry. Dev. Cell 2010, 19, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nikonova, A.S.; Deneka, A.Y.; Kiseleva, A.A.; Korobeynikov, V.; Gaponova, A.; Serebriiskii, I.G.; Kopp, M.C.; Hensley, H.H.; Seeger-Nukpezah, T.N.; Somlo, S.; et al. Ganetespib limits ciliation and cystogenesis in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). FASEB J. 2018, 32, 2735–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sasaki, S.; Shionoya, A.; Ishida, M.; Gambello, M.J.; Yingling, J.; Wynshaw-Boris, A.; Hirotsune, S. A LIS1/NUDEL/cytoplasmic dynein heavy chain complex in the developing and adult nervous system. Neuron 2000, 28, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Niethammer, M.; Smith, D.S.; Ayala, R.; Peng, J.; Ko, J.; Lee, M.S.; Morabito, M.; Tsai, L.H. NUDEL is a novel Cdk5 substrate that associates with LIS1 and cytoplasmic dynein. Neuron 2000, 28, 697–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pugacheva, E.N.; Golemis, E.A. The focal adhesion scaffolding protein HEF1 regulates activation of the Aurora-A and Nek2 kinases at the centrosome. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005, 7, 937–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ice, R.J.; McLaughlin, S.L.; Livengood, R.H.; Culp, M.V.; Eddy, E.R.; Ivanov, A.V.; Pugacheva, E.N. NEDD9 depletion destabilizes Aurora A kinase and heightens the efficacy of Aurora A inhibitors: Implications for treatment of metastatic solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 3168–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Plotnikova, O.V.; Pugacheva, E.N.; Dunbrack, R.L.; Golemis, E.A. Rapid calcium-dependent activation of Aurora-A kinase. Nat. Commun. 2010, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ding, C.; Fan, X.; Wu, G. Peroxiredoxin 1—an antioxidant enzyme in cancer. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledgerwood, E.C.; Marshall, J.W.; Weijman, J.F. The role of peroxiredoxin 1 in redox sensing and transducing. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2017, 617, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shagisultanova, E.; Gaponova, A.V.; Gabbasov, R.; Nicolas, E.; Golemis, E.A. Preclinical and clinical studies of the NEDD9 scaffold protein in cancer and other diseases. Gene 2015, 567, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nikonova, A.S.; Plotnikova, O.V.; Serzhanova, V.; Efimov, A.; Bogush, I.; Cai, K.Q.; Hensley, H.H.; Egleston, B.L.; Klein-Szanto, A.; Seeger-Nukpezah, T.; et al. Nedd9 restrains renal cystogenesis in Pkd1-/- mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 12859–12864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riazuddin, S.A.; Iqbal, M.; Wang, Y.; Masuda, T.; Chen, Y.; Bowne, S.; Sullivan, L.S.; Waseem, N.H.; Bhattacharya, S.; Daiger, S.P.; et al. A splice-site mutation in a retina-specific exon of BBS8 causes nonsyndromic retinitis pigmentosa. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010, 86, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goyal, S.; Jäger, M.; Robinson, P.N.; Vanita, V. Confirmation of TTC8 as a disease gene for nonsyndromic autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa (RP51). Clin. Genet. 2016, 89, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May-Simera, H.L.; Wan, Q.; Jha, B.S.; Hartford, J.; Khristov, V.; Dejene, R.; Chang, J.; Patnaik, S.; Lu, Q.; Banerjee, P.; et al. Primary cilium-mediated retinal pigment epithelium maturation is disrupted in ciliopathy patient cells. Cell Rep. 2018, 22, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ansley, S.J.; Badano, J.L.; Blacque, O.E.; Hill, J.; Hoskins, B.E.; Leitch, C.C.; Kim, J.C.; Ross, A.J.; Eichers, E.R.; Teslovich, T.M.; et al. Basal body dysfunction is a likely cause of pleiotropic Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Nature 2003, 425, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patnaik, S.R.; Kretschmer, V.; Brücker, L.; Schneider, S.; Volz, A.K.; Oancea-Castillo, L.D.R.; May-Simera, H.L. Bardet-Biedl Syndrome proteins regulate cilia disassembly during tissue maturation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2019, 76, 757–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frosk, P.; Arts, H.H.; Philippe, J.; Gunn, C.S.; Brown, E.L.; Chodirker, B.; Simard, L.; Majewski, J.; Fahiminiya, S.; Russell, C.; et al. A truncating mutation in CEP55 is the likely cause of MARCH, a novel syndrome affecting neuronal mitosis. J. Med. Genet. 2017, 54, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondeson, M.L.; Ericson, K.; Gudmundsson, S.; Ameur, A.; Pontén, F.; Wesström, J.; Frykholm, C.; Wilbe, M. A nonsense mutation in CEP55 defines a new locus for a Meckel-like syndrome, an autosomal recessive lethal fetal ciliopathy. Clin. Genet. 2017, 92, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlins, L.E.; Jones, H.; Wenger, O.; Aye, M.; Fasham, J.; Harlalka, G.V.; Chioza, B.A.; Miron, A.; Ellard, S.; Wakeling, M.; et al. An Amish founder variant consolidates disruption of CEP55 as a cause of hydranencephaly and renal dysplasia. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 27, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-C.; Bai, Y.-F.; Yuan, J.-F.; Shen, X.-L.; Xu, Y.-L.; Jian, X.-X.; Li, S.; Song, Z.-Q.; Hu, H.-B.; Li, P.-Y.; et al. CEP55 promotes cilia disassembly through stabilizing Aurora A kinase. J. Cell Biol. 2021, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Liu, M.; Wang, H.; Yu, S.; Jiang, Z.; Sun, J.; Han, K.; Shen, J.; Zhu, M.; Lin, Z.; et al. Centrosomal Protein of 55 Regulates Glucose Metabolism, Proliferation and Apoptosis of Glioma Cells via the Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway. J. Cancer 2016, 7, 1431–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhu, H.; Chen, D.; Tang, J.; Huang, C.; Lv, S.; Wang, D.; Li, G. Overexpression of centrosomal protein 55 regulates the proliferation of glioma cell and mediates proliferation promoted by EGFRvIII in glioblastoma U251 cells. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 2700–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaria, J.P.; Campa, C.C.; De Santis, M.C.; Hirsch, E.; Franco, I. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in polycystic kidney disease: A complex interaction with polycystins and primary cilium. Cell Signal. 2020, 66, 109468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manning, B.D.; Toker, A. AKT/PKB Signaling: Navigating the Network. Cell 2017, 169, 381–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thoma, C.R.; Frew, I.J.; Hoerner, C.R.; Montani, M.; Moch, H.; Krek, W. pVHL and GSK3beta are components of a primary cilium-maintenance signalling network. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beurel, E.; Grieco, S.F.; Jope, R.S. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3): Regulation, actions, and diseases. Pharm. Ther. 2015, 148, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, X.; Lowry, P.R.; Zhou, X.; Depry, C.; Wei, Z.; Wong, G.W.; Zhang, J. PI3K/Akt signaling requires spatial compartmentalization in plasma membrane microdomains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 14509–14514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, J.; Otis, J.M.; Suciu, S.K.; Catalano, C.; Xing, L.; Constable, S.; Wachten, D.; Gupton, S.; Lee, J.; Lee, A.; et al. Primary Cilia Signaling Promotes Axonal Tract Development and Is Disrupted in Joubert Syndrome-Related Disorders Models. Dev. Cell 2019, 51, 759–774.e755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forcioli-Conti, N.; Lacas-Gervais, S.; Dani, C.; Peraldi, P. The primary cilium undergoes dynamic size modifications during adipocyte differentiation of human adipose stem cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 458, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engle, S.E.; Bansal, R.; Antonellis, P.J.; Berbari, N.F. Cilia signaling and obesity. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, D.; Shi, S.; Wang, H.; Liao, K. Growth arrest induces primary-cilium formation and sensitizes IGF-1-receptor signaling during differentiation induction of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. J. Cell Sci. 2009, 122, 2760–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dalbay, M.T.; Thorpe, S.D.; Connelly, J.T.; Chapple, J.P.; Knight, M.M. Adipogenic Differentiation of hMSCs is Mediated by Recruitment of IGF-1r Onto the Primary Cilium Associated With Cilia Elongation. Stem Cells 2015, 33, 1952–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haczeyni, F.; Bell-Anderson, K.S.; Farrell, G.C. Causes and mechanisms of adipocyte enlargement and adipose expansion. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopinke, D.; Roberson, E.C.; Reiter, J.F. Ciliary Hedgehog Signaling Restricts Injury-Induced Adipogenesis. Cell 2017, 170, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Huo, H.; Guo, X.; Hong, S.; Jiang, M.; Liu, X.; Liao, K. Lipid rafts/caveolae are essential for insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor signaling during 3T3-L1 preadipocyte differentiation induction. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 11561–11569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sánchez-Wandelmer, J.; Dávalos, A.; Herrera, E.; Giera, M.; Cano, S.; de la Peña, G.; Lasunción, M.A.; Busto, R. Inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis disrupts lipid raft/caveolae and affects insulin receptor activation in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta 2009, 1788, 1731–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levental, I.; Levental, K.R.; Heberle, F.A. Lipid Rafts: Controversies Resolved, Mysteries Remain. Trends Cell Biol. 2020, 30, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, E.; Levental, I.; Mayor, S.; Eggeling, C. The mystery of membrane organization: Composition, regulation and roles of lipid rafts. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Deventer, S.; Arp, A.B.; van Spriel, A.B. Dynamic Plasma Membrane Organization: A Complex Symphony. Trends Cell Biol. 2021, 31, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pike, L.J. Rafts defined: A report on the Keystone Symposium on Lipid Rafts and Cell Function. J. Lipid Res. 2006, 47, 1597–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simons, K.; Sampaio, J.L. Membrane organization and lipid rafts. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, a004697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hryniewicz-Jankowska, A.; Augoff, K.; Sikorski, A.F. The role of cholesterol and cholesterol-driven membrane raft domains in prostate cancer. Exp. Biol. Med. 2019, 244, 1053–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenlee, J.D.; Subramanian, T.; Liu, K.; King, M.R. Rafting Down the Metastatic Cascade: The Role of Lipid Rafts in Cancer Metastasis, Cell Death, and Clinical Outcomes. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beloribi-Djefaflia, S.; Vasseur, S.; Guillaumond, F. Lipid metabolic reprogramming in cancer cells. Oncogenesis 2016, 5, e189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pike, L.J. Growth factor receptors, lipid rafts and caveolae: An evolving story. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2005, 1746, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Delos Santos, R.C.; Garay, C.; Antonescu, C.N. Charming neighborhoods on the cell surface: Plasma membrane microdomains regulate receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Cell. Signal. 2015, 27, 1963–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julien, S.; Bobowski, M.; Steenackers, A.; Le Bourhis, X.; Delannoy, P. How Do Gangliosides Regulate RTKs Signaling? Cells 2013, 2, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, S.M.; Fairn, G.D. Mesoscale organization of domains in the plasma membrane—Beyond the lipid raft. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 53, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollinedo, F.; Gajate, C. Lipid rafts as major platforms for signaling regulation in cancer. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2015, 57, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollinedo, F.; Gajate, C. Lipid rafts as signaling hubs in cancer cell survival/death and invasion: Implications in tumor progression and therapy. J. Lipid. Res. 2020, 61, 611–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nishimura, Y.; Yamakawa, D.; Uchida, K.; Shiromizu, T.; Watanabe, M.; Inagaki, M. Primary cilia and lipid raft dynamics. Open Biol. 2021, 11, 210130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veland, I.R.; Awan, A.; Pedersen, L.B.; Yoder, B.K.; Christensen, S.T. Primary cilia and signaling pathways in mammalian development, health and disease. Nephron. Physiol. 2009, 111, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stahlhut, M.; van Deurs, B. Identification of filamin as a novel ligand for caveolin-1: Evidence for the organization of caveolin-1-associated membrane domains by the actin cytoskeleton. Mol. Biol. Cell 2000, 11, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Echarri, A.; Del Pozo, M.A. Caveolae—mechanosensitive membrane invaginations linked to actin filaments. J. Cell Sci. 2015, 128, 2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Matthaeus, C.; Taraska, J.W. Energy and Dynamics of Caveolae Trafficking. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 8, 614472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sviridov, D.; Mukhamedova, N.; Miller, Y.I. Lipid rafts as a therapeutic target. J. Lipid. Res. 2020, 61, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miller, Y.I.; Navia-Pelaez, J.M.; Corr, M.; Yaksh, T.L. Lipid rafts in glial cells: Role in neuroinflammation and pain processing. J. Lipid. Res. 2020, 61, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vona, R.; Iessi, E.; Matarrese, P. Role of Cholesterol and Lipid Rafts in Cancer Signaling: A Promising Therapeutic Opportunity? Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 622908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, A.; Neumann, N.M.; Raleigh, D.R.; Lang, U.E. Clinical Implications of Primary Cilia in Skin Cancer. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 10, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Coelho, P.A.; Bury, L.; Shahbazi, M.N.; Liakath-Ali, K.; Tate, P.H.; Wormald, S.; Hindley, C.J.; Huch, M.; Archer, J.; Skarnes, W.C.; et al. Over-expression of Plk4 induces centrosome amplification, loss of primary cilia and associated tissue hyperplasia in the mouse. Open Biol. 2015, 5, 150209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dufour, J.; Viennois, E.; De Boussac, H.; Baron, S.; Lobaccaro, J.M. Oxysterol receptors, AKT and prostate cancer. Curr. Opin. Pharm. 2012, 12, 724–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nechipurenko, I.V. The Enigmatic Role of Lipids in Cilia Signaling. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eramo, M.J.; Mitchell, C.A. Regulation of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3/Akt signalling by inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatases. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2016, 44, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bielas, S.L.; Silhavy, J.L.; Brancati, F.; Kisseleva, M.V.; Al-Gazali, L.; Sztriha, L.; Bayoumi, R.A.; Zaki, M.S.; Abdel-Aleem, A.; Rosti, R.O.; et al. Mutations in INPP5E, encoding inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase E, link phosphatidyl inositol signaling to the ciliopathies. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 1032–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hakim, S.; Dyson, J.M.; Feeney, S.J.; Davies, E.M.; Sriratana, A.; Koenig, M.N.; Plotnikova, O.V.; Smyth, I.M.; Ricardo, S.D.; Hobbs, R.M.; et al. Inpp5e suppresses polycystic kidney disease via inhibition of PI3K/Akt-dependent mTORC1 signaling. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016, 25, 2295–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Jin, M.; Hu, R.; Wang, H.; Zhang, F.; Yuan, S.; Cao, Y. The Joubert Syndrome Protein Inpp5e Controls Ciliogenesis by Regulating Phosphoinositides at the Apical Membrane. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 28, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra Potchanant, E.A.; Cerabona, D.; Sater, Z.A.; He, Y.; Sun, Z.; Gehlhausen, J.; Nalepa, G. INPP5E Preserves Genomic Stability through Regulation of Mitosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2017, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ivan, M.; Kondo, K.; Yang, H.; Kim, W.; Valiando, J.; Ohh, M.; Salic, A.; Asara, J.M.; Lane, W.S.; Kaelin, W.G.J. HIFalpha targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation: Implications for O2 sensing. Science 2001, 292, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, A.C.; Gleadle, J.M.; McNeill, L.A.; Hewitson, K.S.; O’Rourke, J.; Mole, D.R.; Mukherji, M.; Metzen, E.; Wilson, M.I.; Dhanda, A.; et al. C. elegans EGL-9 and mammalian homologs define a family of dioxygenases that regulate HIF by prolyl hydroxylation. Cell 2001, 107, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hon, W.C.; Wilson, M.I.; Harlos, K.; Claridge, T.D.; Schofield, C.J.; Pugh, C.W.; Maxwell, P.H.; Ratcliffe, P.J.; Stuart, D.I.; Jones, E.Y. Structural basis for the recognition of hydroxyproline in HIF-1 alpha by pVHL. Nature 2002, 417, 975–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossage, L.; Eisen, T.; Maher, E.R. VHL, the story of a tumour suppressor gene. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chittiboina, P.; Lonser, R.R. Von Hippel-Lindau disease. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2015, 132, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lutz, M.S.; Burk, R.D. Primary cilium formation requires von hippel-lindau gene function in renal-derived cells. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 6903–6907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, J.; Chakraborty, A.A.; Liu, P.; Gan, W.; Zheng, X.; Inuzuka, H.; Wang, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Yuan, M.; et al. pVHL suppresses kinase activity of Akt in a proline-hydroxylation-dependent manner. Science 2016, 353, 929–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Minervini, G.; Pennuto, M.; Tosatto, S.C.E. The pVHL neglected functions, a tale of hypoxia-dependent and -independent regulations in cancer. Open Biol. 2020, 10, 200109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, P.; Perera, D.; Powell, R.T.; Talley, T.; Tripathi, D.N.; Park, Y.S.; Mancini, M.A.; Davies, P.; Stephan, C.; Corfa, C.; et al. Therapeutically actionable signaling node to rescue AURKA driven loss of primary cilia in VHL-deficient cells. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Yoshizato, T.; Shiraishi, Y.; Maekawa, S.; Okuno, Y.; Kamura, T.; Shimamura, T.; Sato-Otsubo, A.; Nagae, G.; Suzuki, H.; et al. Integrated molecular analysis of clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlinger, M.; Horswell, S.; Larkin, J.; Rowan, A.J.; Salm, M.P.; Varela, I.; Fisher, R.; McGranahan, N.; Matthews, N.; Santos, C.R.; et al. Genomic architecture and evolution of clear cell renal cell carcinomas defined by multiregion sequencing. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Ji, Z. Generation of autochthonous mouse models of clear cell renal cell carcinoma: Mouse models of renal cell carcinoma. Exp. Mol. Med. 2018, 50, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, H.; German, P.; Bai, S.; Barnes, S.; Guo, W.; Qi, X.; Lou, H.; Liang, J.; Jonasch, E.; Mills, G.B.; et al. The PI3K/AKT Pathway and Renal Cell Carcinoma. J. Genet. Genom. 2015, 42, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cohen, P.; Cross, D.; Jänne, P.A. Kinase drug discovery 20 years after imatinib: Progress and future directions. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntyre, P.J.; Collins, P.M.; Vrzal, L.; Birchall, K.; Arnold, L.H.; Mpamhanga, C.; Coombs, P.J.; Burgess, S.G.; Richards, M.W.; Winter, A.; et al. Characterization of Three Druggable Hot-Spots in the Aurora-A/TPX2 Interaction Using Biochemical, Biophysical, and Fragment-Based Approaches. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017, 12, 2906–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Narvaez, A.J.; Ber, S.; Crooks, A.; Emery, A.; Hardwick, B.; Guarino Almeida, E.; Huggins, D.J.; Perera, D.; Roberts-Thomson, M.; Azzarelli, R.; et al. Modulating Protein-Protein Interactions of the Mitotic Polo-like Kinases to Target Mutant KRAS. Cell Chem. Biol. 2017, 24, 1017–1028.e1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ran, X.; Gestwicki, J.E. Inhibitors of protein–protein interactions (PPIs): An analysis of scaffold choices and buried surface area. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2018, 44, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kufer, T.A.; Silljé, H.H.; Körner, R.; Gruss, O.J.; Meraldi, P.; Nigg, E.A. Human TPX2 is required for targeting Aurora-A kinase to the spindle. J. Cell Biol. 2002, 158, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bird, A.W.; Hyman, A.A. Building a spindle of the correct length in human cells requires the interaction between TPX2 and Aurora A. J. Cell Biol. 2008, 182, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gupta, P.; Mohanty, D. SMMPPI: A machine learning-based approach for prediction of modulators of protein-protein interactions and its application for identification of novel inhibitors for RBD:hACE2 interactions in SARS-CoV-2. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Yun, J.S.; Song, H.; Kim, N.H.; Kim, H.S.; Yook, J.I. Exploring the chemical space of protein–protein interaction inhibitors through machine learning. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zhou, Q.; He, J.; Jiang, Z.; Peng, C.; Tong, R.; Shi, J. Recent advances in the development of protein–protein interactions modulators: Mechanisms and clinical trials. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, A.C.; Crews, C.M. Induced protein degradation: An emerging drug discovery paradigm. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naito, M.; Ohoka, N.; Shibata, N. SNIPERs-Hijacking IAP activity to induce protein degradation. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2019, 31, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Lv, W.; Rao, Y. Opportunities and Challenges of Small Molecule Induced Targeted Protein Degradation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnew, H.D.; Coppock, M.B.; Idso, M.N.; Lai, B.T.; Liang, J.; McCarthy-Torrens, A.M.; Warren, C.M.; Heath, J.R. Protein-Catalyzed Capture Agents. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 9950–9970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Feng, F.; Liu, W.; Sun, H. Degradation of proteins by PROTACs and other strategies. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2020, 10, 207–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sells, T.B.; Chau, R.; Ecsedy, J.A.; Gershman, R.E.; Hoar, K.; Huck, J.; Janowick, D.A.; Kadambi, V.J.; LeRoy, P.J.; Stirling, M.; et al. MLN8054 and Alisertib (MLN8237): Discovery of Selective Oral Aurora A Inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, I.; Erickson, E.C.; Donovan, K.A.; Eleuteri, N.A.; Fischer, E.S.; Gray, N.S.; Toker, A. Discovery of an AKT Degrader with Prolonged Inhibition of Downstream Signaling. Cell Chem. Biol. 2020, 27, 66–73.e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, R.K.; Varghese, J.O.; Das, S.; Nag, A.; Tang, G.; Tang, K.; Sutherland, A.M.; Heath, J.R. Degradation of Akt using protein-catalyzed capture agents. J. Pept. Sci. 2016, 22, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brès, V.; Yoh, S.M.; Jones, K.A. The multi-tasking P-TEFb complex. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2008, 20, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bechter, O.; Schöffski, P. Make your best BET: The emerging role of BET inhibitor treatment in malignant tumors. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 208, 107479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.L.; Xu, L.; Han, B.C.; Shyamsunder, P.; Chng, W.J.; Koeffler, H.P. Multiple myeloma: Combination therapy of BET proteolysis targeting chimeric molecule with CDK9 inhibitor. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, S.-M.; Dong, J.; Xu, Z.-Y.; Cheng, X.-D.; Zhang, W.-D.; Qin, J.-J. PROTAC: An Effective Targeted Protein Degradation Strategy for Cancer Therapy. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolin, G.; Sizaire, F.; Herbomel, G.; Reboutier, D.; Prigent, C.; Tramier, M. A FRET biosensor reveals spatiotemporal activation and functions of aurora kinase A in living cells. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Miura, H.; Matsuda, M.; Aoki, K. Development of a FRET Biosensor with High Specificity for Akt. Cell Struct. Funct. 2014, 39, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Agarwal, S.R.; Gratwohl, J.; Cozad, M.; Yang, P.C.; Clancy, C.E.; Harvey, R.D. Compartmentalized cAMP Signaling Associated With Lipid Raft and Non-raft Membrane Domains in Adult Ventricular Myocytes. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.Y.; Falcone, J.L.; Curci, S.; Hofer, A.M. Direct visualization of cAMP signaling in primary cilia reveals up-regulation of ciliary GPCR activity following Hedgehog activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 12066–12071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, K.L.; Guevarra, M.D.; Nguyen, A.M.; Chua, M.C.; Wang, Y.; Jacobs, C.R. The primary cilium functions as a mechanical and calcium signaling nexus. Cilia 2015, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ni, Q.; Titov, D.V.; Zhang, J. Analyzing protein kinase dynamics in living cells with FRET reporters. Methods 2006, 40, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Jansen, V.; Jikeli, J.F.; Hamzeh, H.; Alvarez, L.; Dombrowski, M.; Balbach, M.; Strünker, T.; Seifert, R.; Kaupp, U.B.; et al. A novel biosensor to study cAMP dynamics in cilia and flagella. eLife 2016, 5, e14052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslanhan, M.D.; Gulensoy, D.; Firat-Karalar, E.N. A Proximity Mapping Journey into the Biology of the Mammalian Centrosome/Cilium Complex. Cells 2020, 9, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devi, R.; Pelletier, L.; Prosser, S.L. Charting the complex composite nature of centrosomes, primary cilia and centriolar satellites. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2021, 66, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Carruthers, N.; Lee, J.; Chinni, S.; Stemmer, P. Classification-based quantitative analysis of stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) data. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2016, 137, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duggal, S.; Jailkhani, N.; Midha, M.K.; Agrawal, N.; Rao, K.V.S.; Kumar, A. Defining the Akt1 interactome and its role in regulating the cell cycle. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nishimura, Y.; Yamakawa, D.; Shiromizu, T.; Inagaki, M. Aurora A and AKT Kinase Signaling Associated with Primary Cilia. Cells 2021, 10, 3602. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10123602

Nishimura Y, Yamakawa D, Shiromizu T, Inagaki M. Aurora A and AKT Kinase Signaling Associated with Primary Cilia. Cells. 2021; 10(12):3602. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10123602

Chicago/Turabian StyleNishimura, Yuhei, Daishi Yamakawa, Takashi Shiromizu, and Masaki Inagaki. 2021. "Aurora A and AKT Kinase Signaling Associated with Primary Cilia" Cells 10, no. 12: 3602. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10123602

APA StyleNishimura, Y., Yamakawa, D., Shiromizu, T., & Inagaki, M. (2021). Aurora A and AKT Kinase Signaling Associated with Primary Cilia. Cells, 10(12), 3602. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10123602