Arrhythmogenic Remodeling in the Failing Heart

Abstract

1. Introduction

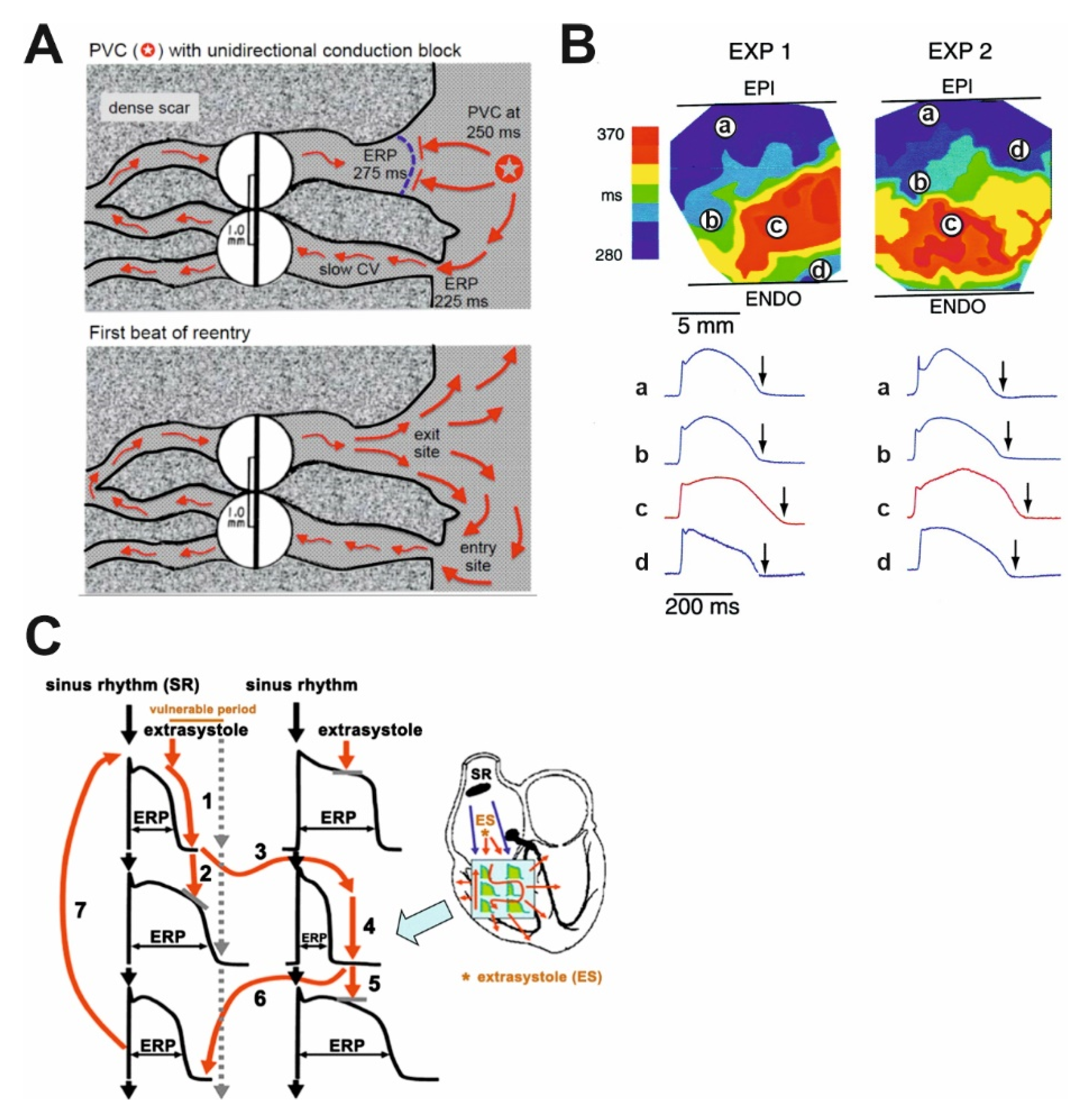

2. The Proposed Electrophysiological Mechanism of Arrhythmias Leading to Sudden Cardiac Death in HF

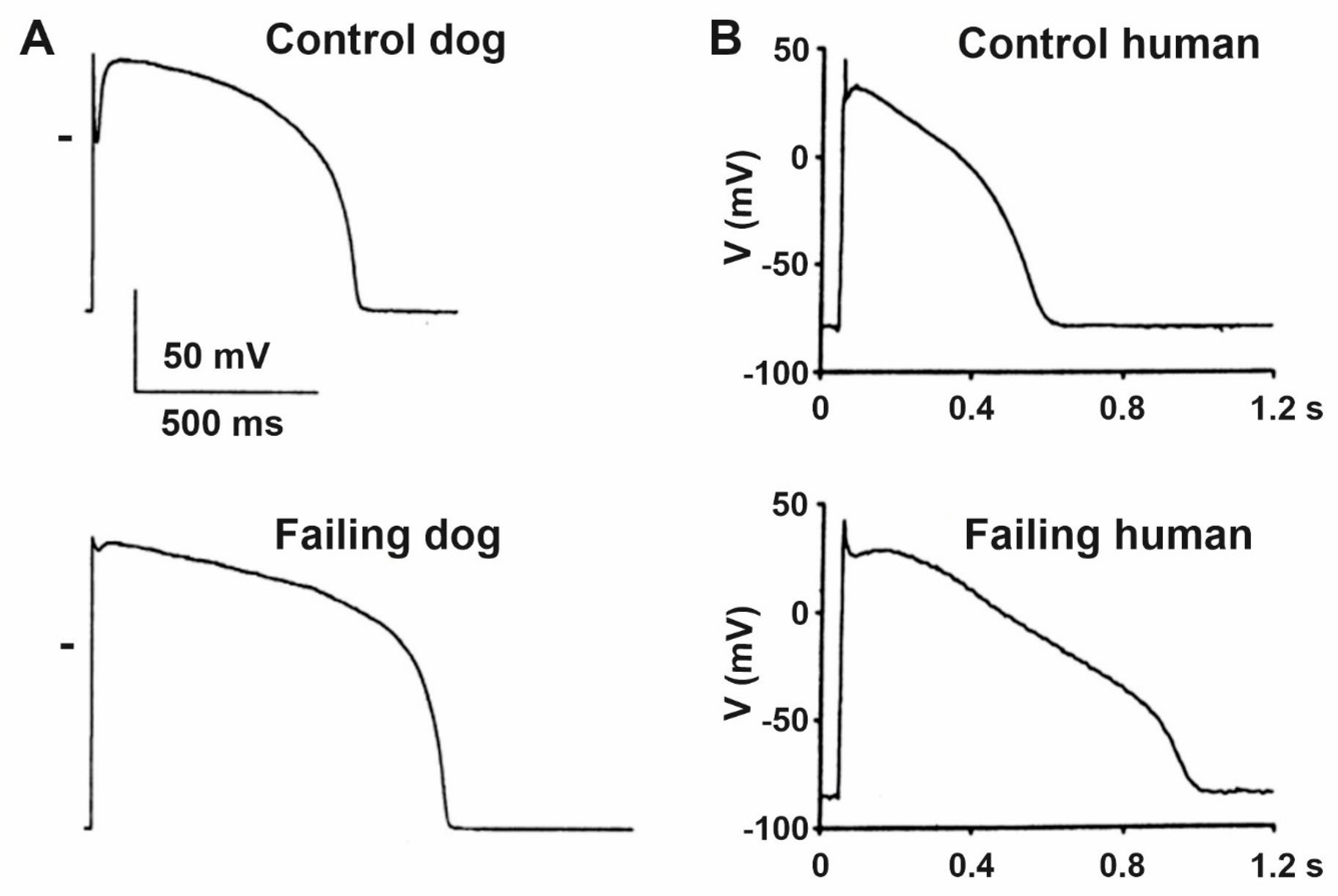

3. Heart Failure and the Cardiac Action Potential

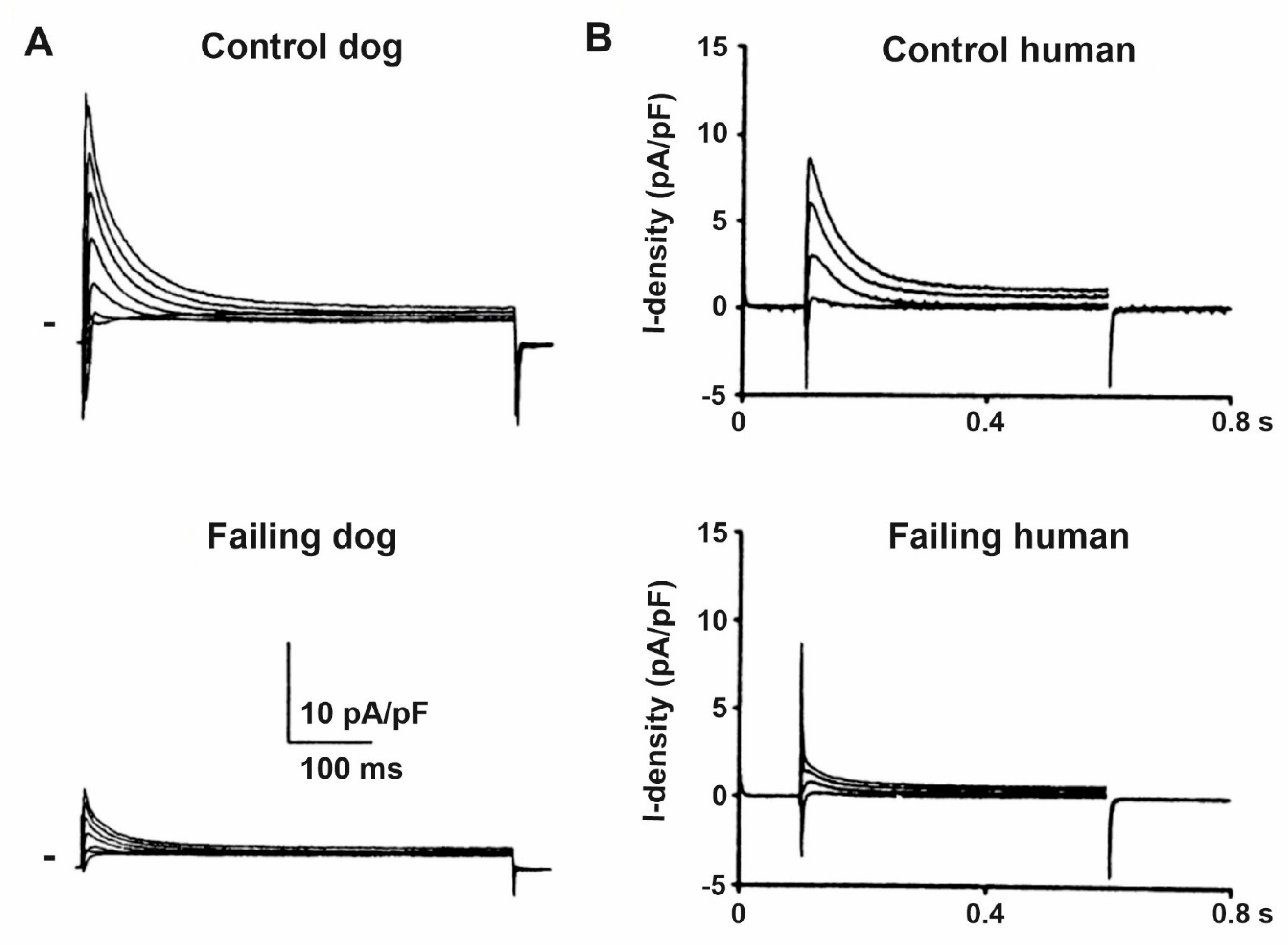

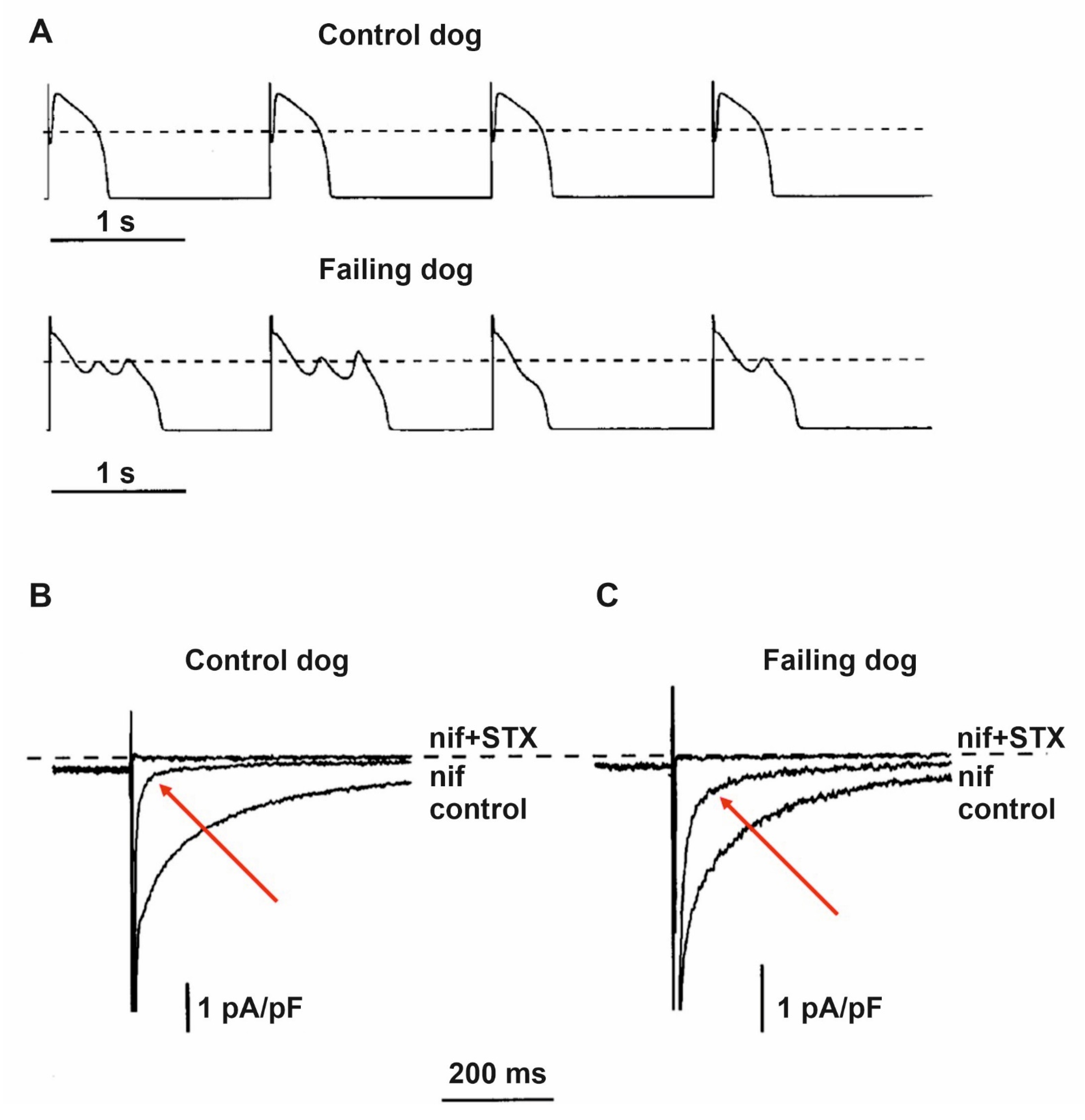

4. Remodeling of Repolarizing Transmembrane Currents in HF

5. Impaired Impulse Conduction in Heart Failure

6. Altered Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) Channels in Heart Failure

7. Alterations of Calcium Handling in Heart Failure

8. Changes of the Pacemaker Current (If) in HF

9. Changes in Cardiac Chloride Currents in the Failing Heart

10. Atrial Remodeling in the Presence of Chronic Heart Failure

11. Need for Novel ECG Parameters for Improved Risk Stratification of Sudden Cardiac Death in HF

12. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jones, N.R.; Roalfe, A.K.; Adoki, I.; Hobbs, F.D.R.; Taylor, C.J. Survival of patients with chronic heart failure in the community: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 1306–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kjekshus, J. Arrhythmias and mortality in congestive heart failure. Am. J. Cardiol. 1990, 65, 42I–48I. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Jhund, P.S.; Petrie, M.C.; Claggett, B.L.; Barlera, S.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Dargie, H.J.; Granger, C.B.; Kjekshus, J.; Kober, L.; et al. Declining Risk of Sudden Death in Heart Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Bohm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Celutkiene, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenewegen, A.; Rutten, F.H.; Mosterd, A.; Hoes, A.W. Epidemiology of heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 1342–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaduganathan, M.; Claggett, B.L.; Chatterjee, N.A.; Anand, I.S.; Sweitzer, N.K.; Fang, J.C.; O’Meara, E.; Shah, S.J.; Hegde, S.M.; Desai, A.S.; et al. Sudden Death in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Competing Risks Analysis from the TOPCAT Trial. JACC Heart Fail. 2018, 6, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adabag, S.; Rector, T.S.; Anand, I.S.; McMurray, J.J.; Zile, M.; Komajda, M.; McKelvie, R.S.; Massie, B.; Carson, P.E. A prediction model for sudden cardiac death in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2014, 16, 1175–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.J.; Larson, M.G.; Levy, D.; Vasan, R.S.; Leip, E.P.; Wolf, P.A.; D’Agostino, R.B.; Murabito, J.M.; Kannel, W.B.; Benjamin, E.J. Temporal relations of atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure and their joint influence on mortality: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2003, 107, 2920–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkerk, A.O.; Wilders, R.; Coronel, R.; Ravesloot, J.H.; Verheijck, E.E. Ionic remodeling of sinoatrial node cells by heart failure. Circulation 2003, 108, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, P.; Kistler, P.M.; Morton, J.B.; Spence, S.J.; Kalman, J.M. Remodeling of sinus node function in patients with congestive heart failure: Reduction in sinus node reserve. Circulation 2004, 110, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaab, S.; Nuss, H.B.; Chiamvimonvat, N.; O’Rourke, B.; Pak, P.H.; Kass, D.A.; Marban, E.; Tomaselli, G.F. Ionic mechanism of action potential prolongation in ventricular myocytes from dogs with pacing-induced heart failure. Circ. Res. 1996, 78, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuji, Y.; Opthof, T.; Kamiya, K.; Yasui, K.; Liu, W.; Lu, Z.; Kodama, I. Pacing-induced heart failure causes a reduction of delayed rectifier potassium currents along with decreases in calcium and transient outward currents in rabbit ventricle. Cardiovasc. Res. 2000, 48, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangogiannis, N.G. Cardiac fibrosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, 1450–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akar, F.G.; Yan, G.X.; Antzelevitch, C.; Rosenbaum, D.S. Unique topographical distribution of M cells underlies reentrant mechanism of torsade de pointes in the long-QT syndrome. Circulation 2002, 105, 1247–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.P.; Qu, Z.; Weiss, J.N. Cardiac fibrosis and arrhythmogenesis: The road to repair is paved with perils. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2014, 70, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varro, A.; Baczko, I. Possible mechanisms of sudden cardiac death in top athletes: A basic cardiac electrophysiological point of view. Pflugers Arch. 2010, 460, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.R.; Lau, C.P.; Leung, T.K.; Nattel, S. Ionic current abnormalities associated with prolonged action potentials in cardiomyocytes from diseased human right ventricles. Heart Rhythm. 2004, 1, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.K.; Springer, S.J.; Wang, W.; Dranoff, E.J.; Zhang, Y.; Kanter, E.M.; Yamada, K.A.; Nerbonne, J.M. Differential Expression and Remodeling of Transient Outward Potassium Currents in Human Left Ventricles. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2018, 11, e005914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, V.P., 3rd; Bonilla, I.M.; Vargas-Pinto, P.; Nishijima, Y.; Sridhar, A.; Li, C.; Mowrey, K.; Wright, P.; Velayutham, M.; Kumar, S.; et al. Heart failure duration progressively modulates the arrhythmia substrate through structural and electrical remodeling. Life Sci. 2015, 123, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Pogwizd, S.M.; Schlotthauer, K.; Li, L.; Yuan, W.; Bers, D.M. Arrhythmogenesis and contractile dysfunction in heart failure: Roles of sodium-calcium exchange, inward rectifier potassium current, and residual beta-adrenergic responsiveness. Circ. Res. 2001, 88, 1159–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.R.; Lau, C.P.; Ducharme, A.; Tardif, J.C.; Nattel, S. Transmural action potential and ionic current remodeling in ventricles of failing canine hearts. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2002, 283, H1031–H1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janse, M.J. Electrophysiological changes in heart failure and their relationship to arrhythmogenesis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004, 61, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, R.; Ramirez, R.J.; Oudit, G.Y.; Gidrewicz, D.; Trivieri, M.G.; Zobel, C.; Backx, P.H. Regulation of cardiac excitation-contraction coupling by action potential repolarization: Role of the transient outward potassium current (I(to)). J. Physiol. 2003, 546, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.H.; Rudy, Y. A dynamic model of the cardiac ventricular action potential. II. Afterdepolarizations, triggered activity, and potentiation. Circ. Res. 1994, 74, 1097–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nattel, S.; Maguy, A.; Le Bouter, S.; Yeh, Y.H. Arrhythmogenic ion-channel remodeling in the heart: Heart failure, myocardial infarction, and atrial fibrillation. Physiol. Rev. 2007, 87, 425–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltsev, V.A.; Silverman, N.; Sabbah, H.N.; Undrovinas, A.I. Chronic heart failure slows late sodium current in human and canine ventricular myocytes: Implications for repolarization variability. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2007, 9, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glukhov, A.V.; Fedorov, V.V.; Lou, Q.; Ravikumar, V.K.; Kalish, P.W.; Schuessler, R.B.; Moazami, N.; Efimov, I.R. Transmural dispersion of repolarization in failing and nonfailing human ventricle. Circ. Res. 2010, 106, 981–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Chartier, D.; Li, D.; Nattel, S. Ionic remodeling of cardiac Purkinje cells by congestive heart failure. Circulation 2001, 104, 2095–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logantha, S.; Cai, X.J.; Yanni, J.; Jones, C.B.; Stephenson, R.S.; Stuart, L.; Quigley, G.; Monfredi, O.; Nakao, S.; Oh, I.Y.; et al. Remodeling of the Purkinje Network in Congestive Heart Failure in the Rabbit. Circ. Heart Fail. 2021, 14, e007505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodama, M.; Kato, K.; Hirono, S.; Okura, Y.; Hanawa, H.; Yoshida, T.; Hayashi, M.; Tachikawa, H.; Kashimura, T.; Watanabe, K.; et al. Linkage between mechanical and electrical alternans in patients with chronic heart failure. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2004, 15, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, L.D.; Jeyaraj, D.; Wan, X.; Hoeker, G.S.; Said, T.H.; Gittinger, M.; Laurita, K.R.; Rosenbaum, D.S. Heart failure enhances susceptibility to arrhythmogenic cardiac alternans. Heart Rhythm. 2009, 6, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomek, J.; Tomkova, M.; Zhou, X.; Bub, G.; Rodriguez, B. Modulation of Cardiac Alternans by Altered Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Calcium Release: A Simulation Study. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaselli, G.F.; Beuckelmann, D.J.; Calkins, H.G.; Berger, R.D.; Kessler, P.D.; Lawrence, J.H.; Kass, D.; Feldman, A.M.; Marban, E. Sudden cardiac death in heart failure. The role of abnormal repolarization. Circulation 1994, 90, 2534–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, J.; Armoundas, A.A.; Tian, Y.; DiSilvestre, D.; Burysek, M.; Halperin, V.; O’Rourke, B.; Kass, D.A.; Marban, E.; Tomaselli, G.F. Molecular correlates of altered expression of potassium currents in failing rabbit myocardium. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005, 288, H2077–H2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaab, S.; Dixon, J.; Duc, J.; Ashen, D.; Nabauer, M.; Beuckelmann, D.J.; Steinbeck, G.; McKinnon, D.; Tomaselli, G.F. Molecular basis of transient outward potassium current downregulation in human heart failure: A decrease in Kv4.3 mRNA correlates with a reduction in current density. Circulation 1998, 98, 1383–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akar, F.G.; Wu, R.C.; Juang, G.J.; Tian, Y.; Burysek, M.; Disilvestre, D.; Xiong, W.; Armoundas, A.A.; Tomaselli, G.F. Molecular mechanisms underlying K+ current downregulation in canine tachycardia-induced heart failure. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005, 288, H2887–H2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zicha, S.; Xiao, L.; Stafford, S.; Cha, T.J.; Han, W.; Varro, A.; Nattel, S. Transmural expression of transient outward potassium current subunits in normal and failing canine and human hearts. J. Physiol. 2004, 561, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaborit, N.; Le Bouter, S.; Szuts, V.; Varro, A.; Escande, D.; Nattel, S.; Demolombe, S. Regional and tissue specific transcript signatures of ion channel genes in the non-diseased human heart. J. Physiol. 2007, 582, 675–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.P.; Campbell, D.L. Transient outward potassium current, ‘Ito’, phenotypes in the mammalian left ventricle: Underlying molecular, cellular and biophysical mechanisms. J. Physiol. 2005, 569, 7–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virag, L.; Jost, N.; Papp, R.; Koncz, I.; Kristof, A.; Kohajda, Z.; Harmati, G.; Carbonell-Pascual, B.; Ferrero, J.M., Jr.; Papp, J.G.; et al. Analysis of the contribution of I(to) to repolarization in canine ventricular myocardium. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 164, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Feng, J.; Shi, H.; Pond, A.; Nerbonne, J.M.; Nattel, S. Potential molecular basis of different physiological properties of the transient outward K+ current in rabbit and human atrial myocytes. Circ. Res. 1999, 84, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabauer, M.; Beuckelmann, D.J.; Uberfuhr, P.; Steinbeck, G. Regional differences in current density and rate-dependent properties of the transient outward current in subepicardial and subendocardial myocytes of human left ventricle. Circulation 1996, 93, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radicke, S.; Cotella, D.; Graf, E.M.; Banse, U.; Jost, N.; Varro, A.; Tseng, G.N.; Ravens, U.; Wettwer, E. Functional modulation of the transient outward current Ito by KCNE beta-subunits and regional distribution in human non-failing and failing hearts. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006, 71, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calloe, K.; Nof, E.; Jespersen, T.; Di Diego, J.M.; Chlus, N.; Olesen, S.P.; Antzelevitch, C.; Cordeiro, J.M. Comparison of the effects of a transient outward potassium channel activator on currents recorded from atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2011, 22, 1057–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, J.M.; Calloe, K.; Moise, N.S.; Kornreich, B.; Giannandrea, D.; Di Diego, J.M.; Olesen, S.P.; Antzelevitch, C. Physiological consequences of transient outward K+ current activation during heart failure in the canine left ventricle. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2012, 52, 1291–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varro, A.; Baczko, I. Cardiac ventricular repolarization reserve: A principle for understanding drug-related proarrhythmic risk. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 164, 14–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, E.; Yasui, K.; Kamiya, K.; Yamaguchi, T.; Sakuma, I.; Honjo, H.; Ozaki, Y.; Morimoto, S.; Hishida, H.; Kodama, I. Upregulation of KCNE1 induces QT interval prolongation in patients with chronic heart failure. Circ. J. 2007, 71, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, R.S.; Diness, T.G.; Christ, T.; Demnitz, J.; Ravens, U.; Olesen, S.P.; Grunnet, M. Activation of human ether-a-go-go-related gene potassium channels by the diphenylurea 1,3-bis-(2-hydroxy-5-trifluoromethyl-phenyl)-urea (NS1643). Mol. Pharmacol. 2006, 69, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diness, J.G.; Hansen, R.S.; Nissen, J.D.; Jespersen, T.; Grunnet, M. Antiarrhythmic effect of IKr activation in a cellular model of LQT3. Heart Rhythm. 2009, 6, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salataa, J.J.; Selnickb, H.G.; Lynch, J.J., Jr. Pharmacological modulation of I(Ks): Potential for antiarrhythmic therapy. Curr. Med. Chem. 2004, 11, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, B.; Meyer, R.; Hetzer, R.; Krause, E.G.; Karczewski, P. Identification and expression of delta-isoforms of the multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase in failing and nonfailing human myocardium. Circ. Res. 1999, 84, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Maier, L.S.; Dalton, N.D.; Miyamoto, S.; Ross, J., Jr.; Bers, D.M.; Brown, J.H. The deltaC isoform of CaMKII is activated in cardiac hypertrophy and induces dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Circ. Res. 2003, 92, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.E.; Brown, J.H.; Bers, D.M. CaMKII in myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2011, 51, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.; Hacker, E.; Grandi, E.; Weber, S.L.; Dybkova, N.; Sossalla, S.; Sowa, T.; Fabritz, L.; Kirchhof, P.; Bers, D.M.; et al. Ca/calmodulin kinase II differentially modulates potassium currents. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2009, 2, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Wan, X.; Dennis, A.T.; Bektik, E.; Wang, Z.; Costa, M.G.S.; Fagnen, C.; Venien-Bryan, C.; Xu, X.; Gratz, D.H.; et al. MicroRNA Biophysically Modulates Cardiac Action Potential by Direct Binding to Ion Channel. Circulation 2021, 143, 1597–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, X.W.; Zhang, L.; Guo, Y.F.; Yang, Y.; Wang, D.M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, P.; Niu, Y.F.; Feng, Q.L.; Wu, B.W.; et al. The IK1/Kir2.1 channel agonist zacopride prevents and cures acute ischemic arrhythmias in the rat. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Undrovinas, N.A.; Maltsev, V.A.; Reznikov, V.; Sabbah, H.N.; Undrovinas, A. Post-transcriptional silencing of SCN1B and SCN2B genes modulates late sodium current in cardiac myocytes from normal dogs and dogs with chronic heart failure. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011, 301, H1596–H1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.; Reznikov, V.; Maltsev, V.A.; Undrovinas, N.A.; Sabbah, H.N.; Undrovinas, A. Contribution of sodium channel neuronal isoform Nav1.1 to late sodium current in ventricular myocytes from failing hearts. J. Physiol. 2015, 593, 1409–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdivia, C.R.; Chu, W.W.; Pu, J.; Foell, J.D.; Haworth, R.A.; Wolff, M.R.; Kamp, T.J.; Makielski, J.C. Increased late sodium current in myocytes from a canine heart failure model and from failing human heart. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2005, 38, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltsev, V.A.; Undrovinas, A.I. A multi-modal composition of the late Na+ current in human ventricular cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006, 69, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashambhoy, Y.L.; Winslow, R.L.; Greenstein, J.L. CaMKII-dependent activation of late INa contributes to cellular arrhythmia in a model of the cardiac myocyte. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2011, 2011, 4665–4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sag, C.M.; Mallwitz, A.; Wagner, S.; Hartmann, N.; Schotola, H.; Fischer, T.H.; Ungeheuer, N.; Herting, J.; Shah, A.M.; Maier, L.S.; et al. Enhanced late INa induces proarrhythmogenic SR Ca leak in a CaMKII-dependent manner. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2014, 76, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltsev, V.A.; Reznikov, V.; Undrovinas, N.A.; Sabbah, H.N.; Undrovinas, A. Modulation of late sodium current by Ca2+, calmodulin, and CaMKII in normal and failing dog cardiomyocytes: Similarities and differences. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008, 294, H1597–H1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shryock, J.C.; Song, Y.; Rajamani, S.; Antzelevitch, C.; Belardinelli, L. The arrhythmogenic consequences of increasing late INa in the cardiomyocyte. Cardiovasc. Res. 2013, 99, 600–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, B.; Bers, D.M. The late sodium current in heart failure: Pathophysiology and clinical relevance. ESC Heart Fail. 2014, 1, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belardinelli, L.; Liu, G.; Smith-Maxwell, C.; Wang, W.Q.; El-Bizri, N.; Hirakawa, R.; Karpinski, S.; Li, C.H.; Hu, L.; Li, X.J.; et al. A novel, potent, and selective inhibitor of cardiac late sodium current suppresses experimental arrhythmias. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2013, 344, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltun, D.O.; Parkhill, E.Q.; Elzein, E.; Kobayashi, T.; Jiang, R.H.; Li, X.; Perry, T.D.; Avila, B.; Wang, W.Q.; Hirakawa, R.; et al. Discovery of triazolopyridinone GS-462808, a late sodium current inhibitor (Late INai) of the cardiac Nav1.5 channel with improved efficacy and potency relative to ranolazine. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 3207–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zablocki, J.A.; Elzein, E.; Li, X.; Koltun, D.O.; Parkhill, E.Q.; Kobayashi, T.; Martinez, R.; Corkey, B.; Jiang, H.; Perry, T.; et al. Discovery of Dihydrobenzoxazepinone (GS-6615) Late Sodium Current Inhibitor (Late INai), a Phase II Agent with Demonstrated Preclinical Anti-Ischemic and Antiarrhythmic Properties. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 9005–9017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, B.; Hezso, T.; Kiss, D.; Kistamas, K.; Magyar, J.; Nanasi, P.P.; Banyasz, T. Late Sodium Current Inhibitors as Potential Antiarrhythmic Agents. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Undrovinas, A.I.; Maltsev, V.A.; Sabbah, H.N. Repolarization abnormalities in cardiomyocytes of dogs with chronic heart failure: Role of sustained inward current. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 1999, 55, 494–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobai, I.A.; O’Rourke, B. Enhanced Ca(2+)-activated Na(+)-Ca(2+) exchange activity in canine pacing-induced heart failure. Circ. Res. 2000, 87, 690–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.C.; Mishra, S.; Wang, M.; Jiang, A.; Rastogi, S.; Rousso, B.; Mika, Y.; Sabbah, H.N. Cardiac contractility modulation electrical signals normalize activity, expression, and phosphorylation of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger in heart failure. J. Card. Fail. 2009, 15, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasenfuss, G.; Reinecke, H.; Studer, R.; Pieske, B.; Meyer, M.; Drexler, H.; Just, H. Calcium cycling proteins and force-frequency relationship in heart failure. Basic Res. Cardiol. 1996, 91 (Suppl. 2), 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.; Sabbah, H.N.; Rastogi, S.; Imai, M.; Gupta, R.C. Reduced sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ uptake and increased Na+-Ca2+ exchanger expression in left ventricle myocardium of dogs with progression of heart failure. Heart Vessels 2005, 20, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoons, G.; Willems, R.; Sipido, K.R. Alternative strategies in arrhythmia therapy: Evaluation of Na/Ca exchange as an anti-arrhythmic target. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 134, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, N.; Acsai, K.; Kormos, A.; Sebok, Z.; Farkas, A.S.; Jost, N.; Nanasi, P.P.; Papp, J.G.; Varro, A.; Toth, A. [Ca(2)(+)] i -induced augmentation of the inward rectifier potassium current (IK1) in canine and human ventricular myocardium. Pflugers Arch. 2013, 465, 1621–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Tuteja, D.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Rodriguez, J.; Nie, L.; Tuxson, H.R.; Young, J.N.; Glatter, K.A.; et al. Molecular identification and functional roles of a Ca(2+)-activated K+ channel in human and mouse hearts. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 49085–49094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, N.; Szuts, V.; Horvath, Z.; Seprenyi, G.; Farkas, A.S.; Acsai, K.; Prorok, J.; Bitay, M.; Kun, A.; Pataricza, J.; et al. Does small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel contribute to cardiac repolarization? J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2009, 47, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y.C.; Chang, P.C.; Hsueh, C.H.; Lee, Y.S.; Shen, C.; Weiss, J.N.; Chen, Z.; Ai, T.; Lin, S.F.; Chen, P.S. Apamin-sensitive potassium current modulates action potential duration restitution and arrhythmogenesis of failing rabbit ventricles. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2013, 6, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, I.M.; Long, V.P., 3rd; Vargas-Pinto, P.; Wright, P.; Belevych, A.; Lou, Q.; Mowrey, K.; Yoo, J.; Binkley, P.F.; Fedorov, V.V.; et al. Calcium-activated potassium current modulates ventricular repolarization in chronic heart failure. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e108824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, P.C.; Turker, I.; Lopshire, J.C.; Masroor, S.; Nguyen, B.L.; Tao, W.; Rubart, M.; Chen, P.S.; Chen, Z.; Ai, T. Heterogeneous upregulation of apamin-sensitive potassium currents in failing human ventricles. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2013, 2, e004713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darkow, E.; Nguyen, T.T.; Stolina, M.; Kari, F.A.; Schmidt, C.; Wiedmann, F.; Baczko, I.; Kohl, P.; Rajamani, S.; Ravens, U.; et al. Small Conductance Ca(2+)-Activated K(+) (SK) Channel mRNA Expression in Human Atrial and Ventricular Tissue: Comparison Between Donor, Atrial Fibrillation and Heart Failure Tissue. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 650964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.C.; Hsieh, Y.C.; Hsueh, C.H.; Weiss, J.N.; Lin, S.F.; Chen, P.S. Apamin induces early afterdepolarizations and torsades de pointes ventricular arrhythmia from failing rabbit ventricles exhibiting secondary rises in intracellular calcium. Heart Rhythm. 2013, 10, 1516–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, S.K.; Chang, P.C.; Maruyama, M.; Turker, I.; Shinohara, T.; Shen, M.J.; Chen, Z.; Shen, C.; Rubart-von der Lohe, M.; Lopshire, J.C.; et al. Small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel and recurrent ventricular fibrillation in failing rabbit ventricles. Circ. Res. 2011, 108, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizukami, K.; Yokoshiki, H.; Mitsuyama, H.; Watanabe, M.; Tenma, T.; Takada, S.; Tsutsui, H. Small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ current is upregulated via the phosphorylation of CaMKII in cardiac hypertrophy from spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2015, 309, H1066–H1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Chen, Z.; Chen, P.S.; Rubart, M. Inhibition of Small-Conductance, Ca(2+)-Activated K(+) Current by Ondansetron. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 651267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, D.; Yang, N.; Tian, Z.; Wu, A.Z.; Xu, D.; Chen, M.; Kamp, N.J.; Wang, Z.; Shen, C.; Chen, Z.; et al. Effects of ondansetron on apamin-sensitive small conductance calcium-activated potassium currents in pacing-induced failing rabbit hearts. Heart Rhythm. 2020, 17, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motloch, L.J.; Ishikawa, K.; Xie, C.; Hu, J.; Aguero, J.; Fish, K.M.; Hajjar, R.J.; Akar, F.G. Increased afterload following myocardial infarction promotes conduction-dependent arrhythmias that are unmasked by hypokalemia. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2017, 2, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakakibara, Y.; Furukawa, T.; Singer, D.H.; Jia, H.; Backer, C.L.; Arentzen, C.E.; Wasserstrom, J.A. Sodium current in isolated human ventricular myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 1993, 265, H1301–H1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltsev, V.A.; Sabbab, H.N.; Undrovinas, A.I. Down-regulation of sodium current in chronic heart failure: Effect of long-term therapy with carvedilol. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2002, 59, 1561–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zicha, S.; Maltsev, V.A.; Nattel, S.; Sabbah, H.N.; Undrovinas, A.I. Post-transcriptional alterations in the expression of cardiac Na+ channel subunits in chronic heart failure. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2004, 37, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivaud, M.R.; Agullo-Pascual, E.; Lin, X.; Leo-Macias, A.; Zhang, M.; Rothenberg, E.; Bezzina, C.R.; Delmar, M.; Remme, C.A. Sodium Channel Remodeling in Subcellular Microdomains of Murine Failing Cardiomyocytes. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e007622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motloch, L.J.; Cacheux, M.; Ishikawa, K.; Xie, C.; Hu, J.; Aguero, J.; Fish, K.M.; Hajjar, R.J.; Akar, F.G. Primary Effect of SERCA 2a Gene Transfer on Conduction Reserve in Chronic Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e009598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, S.; Dybkova, N.; Rasenack, E.C.; Jacobshagen, C.; Fabritz, L.; Kirchhof, P.; Maier, S.K.; Zhang, T.; Hasenfuss, G.; Brown, J.H.; et al. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II regulates cardiac Na+ channels. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 3127–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleber, A.G.; Jin, Q. Coupling between cardiac cells—An important determinant of electrical impulse propagation and arrhythmogenesis. Biophys. Rev. 2021, 2, 031301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, E.; Matsushita, T.; Kaba, R.A.; Vozzi, C.; Coppen, S.R.; Khan, N.; Kaprielian, R.; Yacoub, M.H.; Severs, N.J. Altered connexin expression in human congestive heart failure. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2001, 33, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostin, S.; Rieger, M.; Dammer, S.; Hein, S.; Richter, M.; Klovekorn, W.P.; Bauer, E.P.; Schaper, J. Gap junction remodeling and altered connexin43 expression in the failing human heart. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2003, 242, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostin, S.; Dammer, S.; Hein, S.; Klovekorn, W.P.; Bauer, E.P.; Schaper, J. Connexin 43 expression and distribution in compensated and decompensated cardiac hypertrophy in patients with aortic stenosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004, 62, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akar, F.G.; Nass, R.D.; Hahn, S.; Cingolani, E.; Shah, M.; Hesketh, G.G.; DiSilvestre, D.; Tunin, R.S.; Kass, D.A.; Tomaselli, G.F. Dynamic changes in conduction velocity and gap junction properties during development of pacing-induced heart failure. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007, 293, H1223–H1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegerinck, R.F.; de Bakker, J.M.; Opthof, T.; de Jonge, N.; Kirkels, H.; Wilms-Schopman, F.J.; Coronel, R. The effect of enhanced gap junctional conductance on ventricular conduction in explanted hearts from patients with heart failure. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2009, 104, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribulova, N.; Seki, S.; Radosinska, J.; Kaplan, P.; Babusikova, E.; Knezl, V.; Mochizuki, S. Myocardial Ca2+ handling and cell-to-cell coupling, key factors in prevention of sudden cardiac death. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2009, 87, 1120–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, D.; Sato, D.; Jiang, Y.; Ginsburg, K.S.; Ripplinger, C.M.; Bers, D.M. Calcium-Dependent Arrhythmogenic Foci Created by Weakly Coupled Myocytes in the Failing Heart. Circ. Res. 2017, 121, 1379–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurebayashi, N.; Nishizawa, H.; Nakazato, Y.; Kurihara, H.; Matsushita, S.; Daida, H.; Ogawa, Y. Aberrant cell-to-cell coupling in Ca2+-overloaded guinea pig ventricular muscles. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2008, 294, C1419–C1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akar, F.G.; Spragg, D.D.; Tunin, R.S.; Kass, D.A.; Tomaselli, G.F. Mechanisms underlying conduction slowing and arrhythmogenesis in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 2004, 95, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polyakova, V.; Loeffler, I.; Hein, S.; Miyagawa, S.; Piotrowska, I.; Dammer, S.; Risteli, J.; Schaper, J.; Kostin, S. Fibrosis in endstage human heart failure: Severe changes in collagen metabolism and MMP/TIMP profiles. Int. J. Cardiol. 2011, 151, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macia, E.; Dolmatova, E.; Cabo, C.; Sosinsky, A.Z.; Dun, W.; Coromilas, J.; Ciaccio, E.J.; Boyden, P.A.; Wit, A.L.; Duffy, H.S. Characterization of gap junction remodeling in epicardial border zone of healing canine infarcts and electrophysiological effects of partial reversal by rotigaptide. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2011, 4, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamkin, A.; Kiseleva, I.; Lozinsky, I.; Scholz, H. Electrical interaction of mechanosensitive fibroblasts and myocytes in the heart. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2005, 100, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamkin, A.; Kiseleva, I.; Isenberg, G. Activation and inactivation of a non-selective cation conductance by local mechanical deformation of acutely isolated cardiac fibroblasts. Cardiovasc. Res. 2003, 57, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamkin, A.; Kiseleva, I.; Isenberg, G.; Wagner, K.D.; Gunther, J.; Theres, H.; Scholz, H. Cardiac fibroblasts and the mechano-electric feedback mechanism in healthy and diseased hearts. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2003, 82, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenberg, G.; Kazanski, V.; Kondratev, D.; Gallitelli, M.F.; Kiseleva, I.; Kamkin, A. Differential effects of stretch and compression on membrane currents and [Na+]c in ventricular myocytes. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2003, 82, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamkin, A.; Kiseleva, I.; Isenberg, G. Stretch-activated currents in ventricular myocytes: Amplitude and arrhythmogenic effects increase with hypertrophy. Cardiovasc. Res. 2000, 48, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, F.; Morris, C.E. Mechanosensitive ion channels in nonspecialized cells. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1998, 132, 1–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraishi, I.; Takamatsu, T.; Minamikawa, T.; Onouchi, Z.; Fujita, S. Quantitative histological analysis of the human sinoatrial node during growth and aging. Circulation 1992, 85, 2176–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukharev, S.; Anishkin, A. Mechanosensitive channels: What can we learn from ‘simple’ model systems? Trends Neurosci. 2004, 27, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matter, A.; Girardier, L.; Hyde, A.; Blondel, B. Development of sarcoplasmatic reticulum in cultivated myocardial cells. Verh. Anat. Ges. 1969, 63, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kamkin, A.; Kiseleva, I.; Wagner, K.D.; Pylaev, A.; Leiterer, K.P.; Theres, H.; Scholz, H.; Gunther, J.; Isenberg, G. A possible role for atrial fibroblasts in postinfarction bradycardia. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2002, 282, H842–H849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiseleva, I.; Kamkin, A.; Pylaev, A.; Kondratjev, D.; Leiterer, K.P.; Theres, H.; Wagner, K.D.; Persson, P.B.; Gunther, J. Electrophysiological properties of mechanosensitive atrial fibroblasts from chronic infarcted rat heart. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1998, 30, 1083–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maziere, A.M.; van Ginneken, A.C.; Wilders, R.; Jongsma, H.J.; Bouman, L.N. Spatial and functional relationship between myocytes and fibroblasts in the rabbit sinoatrial node. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1992, 24, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camelliti, P.; Devlin, G.P.; Matthews, K.G.; Kohl, P.; Green, C.R. Spatially and temporally distinct expression of fibroblast connexins after sheep ventricular infarction. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004, 62, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Xie, J.; Yu, A.S.; Stock, J.; Du, J.; Yue, L. Role of TRP channels in the cardiovascular system. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2015, 308, H157–H182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, P. Cardiac Remodeling and Disease: SOCE and TRPC Signaling in Cardiac Pathology. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 993, 505–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freichel, M.; Berlin, M.; Schurger, A.; Mathar, I.; Bacmeister, L.; Medert, R.; Frede, W.; Marx, A.; Segin, S.; Londono, J.E.C. TRP Channels in the Heart. In Neurobiology of TRP Channels; Emir, T.L.R., Ed.; Frontiers in Neuroscience: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 149–185. [Google Scholar]

- Avila-Medina, J.; Mayoral-Gonzalez, I.; Dominguez-Rodriguez, A.; Gallardo-Castillo, I.; Ribas, J.; Ordonez, A.; Rosado, J.A.; Smani, T. The Complex Role of Store Operated Calcium Entry Pathways and Related Proteins in the Function of Cardiac, Skeletal and Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Rodriguez, A.; Mayoral-Gonzalez, I.; Avila-Medina, J.; de Rojas-de Pedro, E.S.; Calderon-Sanchez, E.; Diaz, I.; Hmadcha, A.; Castellano, A.; Rosado, J.A.; Benitah, J.P.; et al. Urocortin-2 Prevents Dysregulation of Ca(2+) Homeostasis and Improves Early Cardiac Remodeling After Ischemia and Reperfusion. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilius, B.; Droogmans, G. Ion channels and their functional role in vascular endothelium. Physiol. Rev. 2001, 81, 1415–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owsianik, G.; D’Hoedt, D.; Voets, T.; Nilius, B. Structure-function relationship of the TRP channel superfamily. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006, 156, 61–90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peng, G.; Shi, X.; Kadowaki, T. Evolution of TRP channels inferred by their classification in diverse animal species. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2015, 84, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudet, R. Structural Insights into the Function of TRP Channels. In TRP Ion Channel Function in Sensory Transduction and Cellular Signaling Cascades; Liedtke, W.B., Heller, S., Eds.; Frontiers in Neuroscience: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez, G.; Wedel, B.J.; Aziz, O.; Trebak, M.; Putney, J.W., Jr. The mammalian TRPC cation channels. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2004, 1742, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islas, L.D. Molecular Mechanisms of Temperature Gating in TRP Channels. In Neurobiology of TRP Channels; Emir, T.L.R., Ed.; Frontiers in Neuroscience: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Naziroglu, M.; Braidy, N. Thermo-Sensitive TRP Channels: Novel Targets for Treating Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Pain. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Iribe, G.; Nishida, M.; Naruse, K. Role of TRPC3 and TRPC6 channels in the myocardial response to stretch: Linking physiology and pathophysiology. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2017, 130, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Kodama, D.; Goto, S.; Togari, A. Involvement of TRP channels in the signal transduction of bradykinin in human osteoblasts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 410, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albarran, L.; Lopez, J.J.; Dionisio, N.; Smani, T.; Salido, G.M.; Rosado, J.A. Transient receptor potential ankyrin-1 (TRPA1) modulates store-operated Ca(2+) entry by regulation of STIM1-Orai1 association. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1833, 3025–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhold, K.A.; Schwartz, M.A. Ion Channels in Endothelial Responses to Fluid Shear Stress. Physiology 2016, 31, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawamura, S.; Shirakawa, H.; Nakagawa, T.; Mori, Y.; Kaneko, S. TRP Channels in the Brain: What Are They There For? In Neurobiology of TRP Channels; Emir, T.L.R., Ed.; Frontiers in Neuroscience: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 295–322. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, E.W.; Hood, D.B.; Papst, P.J.; Chapo, J.A.; Minobe, W.; Bristow, M.R.; Olson, E.N.; McKinsey, T.A. Canonical transient receptor potential channels promote cardiomyocyte hypertrophy through activation of calcineurin signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 33487–33496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morine, K.J.; Paruchuri, V.; Qiao, X.; Aronovitz, M.; Huggins, G.S.; DeNofrio, D.; Kiernan, M.S.; Karas, R.H.; Kapur, N.K. Endoglin selectively modulates transient receptor potential channel expression in left and right heart failure. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2016, 25, 478–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Rodriguez, A.; Ruiz-Hurtado, G.; Sabourin, J.; Gomez, A.M.; Alvarez, J.L.; Benitah, J.P. Proarrhythmic effect of sustained EPAC activation on TRPC3/4 in rat ventricular cardiomyocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2015, 87, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, H.; Murakami, M.; Ohba, T.; Takahashi, Y.; Ito, H. TRP channel and cardiovascular disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 118, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, K.; Rainer, P.P.; Shalkey Hahn, V.; Lee, D.I.; Jo, S.H.; Andersen, A.; Liu, T.; Xu, X.; Willette, R.N.; Lepore, J.J.; et al. Combined TRPC3 and TRPC6 blockade by selective small-molecule or genetic deletion inhibits pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 1551–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domes, K.; Patrucco, E.; Loga, F.; Dietrich, A.; Birnbaumer, L.; Wegener, J.W.; Hofmann, F. Murine cardiac growth, TRPC channels, and cGMP kinase I. Pflugers Arch. 2015, 467, 2229–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitajima, N.; Numaga-Tomita, T.; Watanabe, M.; Kuroda, T.; Nishimura, A.; Miyano, K.; Yasuda, S.; Kuwahara, K.; Sato, Y.; Ide, T.; et al. TRPC3 positively regulates reactive oxygen species driving maladaptive cardiac remodeling. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numaga-Tomita, T.; Kitajima, N.; Kuroda, T.; Nishimura, A.; Miyano, K.; Yasuda, S.; Kuwahara, K.; Sato, Y.; Ide, T.; Birnbaumer, L.; et al. TRPC3-GEF-H1 axis mediates pressure overload-induced cardiac fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 39383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dridi, H.; Kushnir, A.; Zalk, R.; Yuan, Q.; Melville, Z.; Marks, A.R. Reply to ‘Mechanisms of ryanodine receptor 2 dysfunction in heart failure’. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 749–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dridi, H.; Kushnir, A.; Zalk, R.; Yuan, Q.; Melville, Z.; Marks, A.R. Intracellular calcium leak in heart failure and atrial fibrillation: A unifying mechanism and therapeutic target. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 732–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, F.J.; Valdivia, H.H. Mechanisms of ryanodine receptor 2 dysfunction in heart failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogwizd, S.M.; Bers, D.M. Cellular basis of triggered arrhythmias in heart failure. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2004, 14, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, A.R. Calcium cycling proteins and heart failure: Mechanisms and therapeutics. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.L.; Eisner, D.A. Calcium Buffering in the Heart in Health and Disease. Circulation 2019, 139, 2358–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, M.; Anderson, M.E. Mechanisms of altered Ca(2)(+) handling in heart failure. Circ. Res. 2013, 113, 690–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siri-Angkul, N.; Dadfar, B.; Jaleel, R.; Naushad, J.; Parambathazhath, J.; Doye, A.A.; Xie, L.H.; Gwathmey, J.K. Calcium and Heart Failure: How Did We Get Here and Where Are We Going? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuckelmann, D.J.; Nabauer, M.; Erdmann, E. Intracellular calcium handling in isolated ventricular myocytes from patients with terminal heart failure. Circulation 1992, 85, 1046–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piacentino, V., 3rd; Weber, C.R.; Chen, X.; Weisser-Thomas, J.; Margulies, K.B.; Bers, D.M.; Houser, S.R. Cellular basis of abnormal calcium transients of failing human ventricular myocytes. Circ. Res. 2003, 92, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armoundas, A.A.; Rose, J.; Aggarwal, R.; Stuyvers, B.D.; O’Rourke, B.; Kass, D.A.; Marban, E.; Shorofsky, S.R.; Tomaselli, G.F.; William Balke, C. Cellular and molecular determinants of altered Ca2+ handling in the failing rabbit heart: Primary defects in SR Ca2+ uptake and release mechanisms. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007, 292, H1607–H1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, B.; Kass, D.A.; Tomaselli, G.F.; Kaab, S.; Tunin, R.; Marban, E. Mechanisms of altered excitation-contraction coupling in canine tachycardia-induced heart failure, I: Experimental studies. Circ. Res. 1999, 84, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, A.R. Ryanodine receptors/calcium release channels in heart failure and sudden cardiac death. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2001, 33, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.T.; Liu, G.S.; Shen, Y.F.; Wang, Y.L.; Tang, Y.; Yang, Y.J. Defective Ca(2+) handling proteins regulation during heart failure. Physiol. Res. 2011, 60, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehrens, X.H.; Lehnart, S.E.; Reiken, S.R.; Marks, A.R. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II phosphorylation regulates the cardiac ryanodine receptor. Circ. Res. 2004, 94, e61–e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, X.; Curran, J.W.; Shannon, T.R.; Bers, D.M.; Pogwizd, S.M. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase modulates cardiac ryanodine receptor phosphorylation and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak in heart failure. Circ. Res. 2005, 97, 1314–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belevych, A.E.; Radwanski, P.B.; Carnes, C.A.; Gyorke, S. ‘Ryanopathy’: Causes and manifestations of RyR2 dysfunction in heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 2013, 98, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanni, J.; D’Souza, A.; Wang, Y.; Li, N.; Hansen, B.J.; Zakharkin, S.O.; Smith, M.; Hayward, C.; Whitson, B.A.; Mohler, P.J.; et al. Silencing miR-370-3p rescues funny current and sinus node function in heart failure. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyett, M.R.; Yanni, J.; Tellez, J.; Bucchi, A.; Mesirca, P.; Cai, X.; Logantha, S.; Wilson, C.; Anderson, C.; Ariyaratnam, J.; et al. Regulation of sinus node pacemaking and atrioventricular node conduction by HCN channels in health and disease. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2021, 166, 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerbai, E.; Pino, R.; Porciatti, F.; Sani, G.; Toscano, M.; Maccherini, M.; Giunti, G.; Mugelli, A. Characterization of the hyperpolarization-activated current, I(f), in ventricular myocytes from human failing heart. Circulation 1997, 95, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerbai, E.; Sartiani, L.; DePaoli, P.; Pino, R.; Maccherini, M.; Bizzarri, F.; DiCiolla, F.; Davoli, G.; Sani, G.; Mugelli, A. The properties of the pacemaker current I(F)in human ventricular myocytes are modulated by cardiac disease. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2001, 33, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerbai, E.; Mugelli, A. I(f) in non-pacemaker cells: Role and pharmacological implications. Pharmacol. Res. 2006, 53, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillitano, F.; Lonardo, G.; Zicha, S.; Varro, A.; Cerbai, E.; Mugelli, A.; Nattel, S. Molecular basis of funny current (If) in normal and failing human heart. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2008, 45, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartiani, L.; Stillitano, F.; Cerbai, E.; Mugelli, A. Electrophysiologic changes in heart failure: Focus on pacemaker channels. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2009, 87, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yampolsky, P.; Koenen, M.; Mosqueira, M.; Geschwill, P.; Nauck, S.; Witzenberger, M.; Seyler, C.; Fink, T.; Kruska, M.; Bruehl, C.; et al. Augmentation of myocardial If dysregulates calcium homeostasis and causes adverse cardiac remodeling. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahinski, A.; Nairn, A.C.; Greengard, P.; Gadsby, D.C. Chloride conductance regulated by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase in cardiac myocytes. Nature 1989, 340, 718–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, R.D.; Hume, J.R. Autonomic regulation of a chloride current in heart. Science 1989, 244, 983–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, G.; Hwang, T.C.; Nastiuk, K.L.; Nairn, A.C.; Gadsby, D.C. The protein kinase A-regulated cardiac Cl− channel resembles the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Nature 1992, 360, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, K.B.; Long, K.J. Properties of a protein kinase C-activated chloride current in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Circ. Res. 1994, 74, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, M.L.; Hume, J.R. Unitary chloride channels activated by protein kinase C in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Circ. Res. 1995, 76, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levesque, P.C.; Hume, J.R. ATPo but not cAMPi activates a chloride conductance in mouse ventricular myocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 1995, 29, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, D.; Ye, L.; Britton, F.; Miller, L.J.; Yamazaki, J.; Horowitz, B.; Hume, J.R. Purinoceptor-coupled Cl− channels in mouse heart: A novel, alternative pathway for CFTR regulation. J. Physiol. 1999, 521 Pt 1, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto-Mizuma, S.; Wang, G.X.; Hume, J.R. P2Y purinergic receptor regulation of CFTR chloride channels in mouse cardiac myocytes. J. Physiol. 2004, 556, 727–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, D.; Ye, L.; Britton, F.; Horowitz, B.; Hume, J.R. A novel anionic inward rectifier in native cardiac myocytes. Circ. Res. 2000, 86, E63–EE71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komukai, K.; Brette, F.; Orchard, C.H. Electrophysiological response of rat atrial myocytes to acidosis. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2002, 283, H715–H724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, D.Y.; Fermini, B.; Nattel, S. Sustained outward current observed after I(to1) inactivation in rabbit atrial myocytes is a novel Cl- current. Am. J. Physiol. 1992, 263, H1967–H1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, D.; Fermini, B.; Nattel, S. Alpha-adrenergic control of volume-regulated Cl- currents in rabbit atrial myocytes. Characterization of a novel ionic regulatory mechanism. Circ. Res. 1995, 77, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, D.; Hume, J.R.; Nattel, S. Evidence that outwardly rectifying Cl− channels underlie volume-regulated Cl− currents in heart. Circ. Res. 1997, 80, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, D.; Winter, C.; Cowley, S.; Hume, J.R.; Horowitz, B. Molecular identification of a volume-regulated chloride channel. Nature 1997, 390, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, D.; Cowley, S.; Horowitz, B.; Hume, J.R. A serine residue in ClC-3 links phosphorylation-dephosphorylation to chloride channel regulation by cell volume. J. Gen. Physiol. 1999, 113, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, D.; Zhong, J.; Hermoso, M.; Satterwhite, C.M.; Rossow, C.F.; Hatton, W.J.; Yamboliev, I.; Horowitz, B.; Hume, J.R. Functional inhibition of native volume-sensitive outwardly rectifying anion channels in muscle cells and Xenopus oocytes by anti-ClC-3 antibody. J. Physiol. 2001, 531, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, D.; Nattel, S. Properties of single outwardly rectifying Cl− channels in heart. Circ. Res. 1994, 75, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermoso, M.; Satterwhite, C.M.; Andrade, Y.N.; Hidalgo, J.; Wilson, S.M.; Horowitz, B.; Hume, J.R. ClC-3 is a fundamental molecular component of volume-sensitive outwardly rectifying Cl− channels and volume regulation in HeLa cells and Xenopus laevis oocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 40066–40074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto-Mizuma, S.; Wang, G.X.; Liu, L.L.; Schegg, K.; Hatton, W.J.; Duan, D.; Horowitz, T.L.; Lamb, F.S.; Hume, J.R. Altered properties of volume-sensitive osmolyte and anion channels (VSOACs) and membrane protein expression in cardiac and smooth muscle myocytes from Clcn3−/− mice. J. Physiol. 2004, 557, 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collier, M.L.; Levesque, P.C.; Kenyon, J.L.; Hume, J.R. Unitary Cl− channels activated by cytoplasmic Ca2+ in canine ventricular myocytes. Circ. Res. 1996, 78, 936–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britton, F.C.; Ohya, S.; Horowitz, B.; Greenwood, I.A. Comparison of the properties of CLCA1 generated currents and I(Cl(Ca)) in murine portal vein smooth muscle cells. J. Physiol. 2002, 539, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Dong, P.H.; Zhang, Z.; Ahmmed, G.U.; Chiamvimonvat, N. Presence of a calcium-activated chloride current in mouse ventricular myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2002, 283, H302–H314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartzell, C.; Putzier, I.; Arreola, J. Calcium-activated chloride channels. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2005, 67, 719–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, A.; Caci, E.; Ferrera, L.; Pedemonte, N.; Barsanti, C.; Sondo, E.; Pfeffer, U.; Ravazzolo, R.; Zegarra-Moran, O.; Galietta, L.J. TMEM16A, a membrane protein associated with calcium-dependent chloride channel activity. Science 2008, 322, 590–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, B.C.; Cheng, T.; Jan, Y.N.; Jan, L.Y. Expression cloning of TMEM16A as a calcium-activated chloride channel subunit. Cell 2008, 134, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.D.; Cho, H.; Koo, J.Y.; Tak, M.H.; Cho, Y.; Shim, W.S.; Park, S.P.; Lee, J.; Lee, B.; Kim, B.M.; et al. TMEM16A confers receptor-activated calcium-dependent chloride conductance. Nature 2008, 455, 1210–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, D.D. Phenomics of cardiac chloride channels. Compr. Physiol. 2013, 3, 667–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, F.; Busch, G.L.; Ritter, M.; Volkl, H.; Waldegger, S.; Gulbins, E.; Haussinger, D. Functional significance of cell volume regulatory mechanisms. Physiol. Rev. 1998, 78, 247–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hume, J.R.; Duan, D.; Collier, M.L.; Yamazaki, J.; Horowitz, B. Anion transport in heart. Physiol. Rev. 2000, 80, 31–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgarten, C.M.; Clemo, H.F. Swelling-activated chloride channels in cardiac physiology and pathophysiology. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2003, 82, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, Y.; Shimizu, T.; Maeno, E.; Tanabe, S.; Wang, X.; Takahashi, N. Volume-sensitive chloride channels involved in apoptotic volume decrease and cell death. J. Membr. Biol. 2006, 209, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dries, D.L.; Exner, D.V.; Gersh, B.J.; Domanski, M.J.; Waclawiw, M.A.; Stevenson, L.W. Atrial fibrillation is associated with an increased risk for mortality and heart failure progression in patients with asymptomatic and symptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction: A retrospective analysis of the SOLVD trials. Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1998, 32, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogensen, U.M.; Jhund, P.S.; Abraham, W.T.; Desai, A.S.; Dickstein, K.; Packer, M.; Rouleau, J.L.; Solomon, S.D.; Swedberg, K.; Zile, M.R.; et al. Type of Atrial Fibrillation and Outcomes in Patients With Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 2490–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisel, W.H.; Stevenson, L.W. Atrial fibrillation in heart failure: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and rationale for therapy. Am. J. Cardiol. 2003, 91, 2D–8D. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, J.; Khairy, P.; Dobrev, D.; Nattel, S. The clinical profile and pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation: Relationships among clinical features, epidemiology, and mechanisms. Circ. Res. 2014, 114, 1453–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E.J.; Wolf, P.A.; D’Agostino, R.B.; Silbershatz, H.; Kannel, W.B.; Levy, D. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 1998, 98, 946–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.C.; Chen, S.A.; Chiang, C.E.; Tai, C.T.; Lee, S.H.; Chiou, C.W.; Ueng, K.C.; Wen, Z.C.; Chen, Y.J.; Huang, J.L.; et al. Effect of high intensity drive train stimulation on dispersion of atrial refractoriness: Role of autonomic nervous system. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1997, 29, 1000–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerheim, P.; Birger-Botkin, S.; Piracha, L.; Olshansky, B. Heart failure and sudden death in patients with tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy and recurrent tachycardia. Circulation 2004, 110, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crijns, H.J.; Van den Berg, M.P.; Van Gelder, I.C.; Van Veldhuisen, D.J. Management of atrial fibrillation in the setting of heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 1997, 18 (Suppl. C), C45–C49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Fareh, S.; Leung, T.K.; Nattel, S. Promotion of atrial fibrillation by heart failure in dogs: Atrial remodeling of a different sort. Circulation 1999, 100, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, S.V.; Workman, A.J. Atrial Electrophysiological Remodeling and Fibrillation in Heart Failure. Clin. Med. Insights Cardiol. 2016, 10, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardin, S.; Li, D.; Thorin-Trescases, N.; Leung, T.K.; Thorin, E.; Nattel, S. Evolution of the atrial fibrillation substrate in experimental congestive heart failure: Angiotensin-dependent and -independent pathways. Cardiovasc. Res. 2003, 60, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, N.; Cardin, S.; Leung, T.K.; Nattel, S. Differences in atrial versus ventricular remodeling in dogs with ventricular tachypacing-induced congestive heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004, 63, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milliez, P.; Deangelis, N.; Rucker-Martin, C.; Leenhardt, A.; Vicaut, E.; Robidel, E.; Beaufils, P.; Delcayre, C.; Hatem, S.N. Spironolactone reduces fibrosis of dilated atria during heart failure in rats with myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. 2005, 26, 2193–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, S.; Lo, L.W.; Chou, Y.H.; Lin, W.L.; Chang, S.L.; Lin, Y.J.; Chen, S.A. Renal denervation regulates the atrial arrhythmogenic substrates through reverse structural remodeling in heart failure rabbit model. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 235, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstein, B.; Libby, E.; Calderone, A.; Nattel, S. Differential behaviors of atrial versus ventricular fibroblasts: A potential role for platelet-derived growth factor in atrial-ventricular remodeling differences. Circulation 2008, 117, 1630–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wakili, R.; Xiao, J.; Wu, C.T.; Luo, X.; Clauss, S.; Dawson, K.; Qi, X.; Naud, P.; Shi, Y.F.; et al. Detailed characterization of microRNA changes in a canine heart failure model: Relationship to arrhythmogenic structural remodeling. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2014, 77, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, T.J.; Ehrlich, J.R.; Zhang, L.; Shi, Y.F.; Tardif, J.C.; Leung, T.K.; Nattel, S. Dissociation between ionic remodeling and ability to sustain atrial fibrillation during recovery from experimental congestive heart failure. Circulation 2004, 109, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, C.E.; Abu-Taha, I.H.; Wang, Q.; Rosello-Diez, E.; Kamler, M.; Nattel, S.; Ravens, U.; Wehrens, X.H.T.; Hove-Madsen, L.; Heijman, J.; et al. Profibrotic, Electrical, and Calcium-Handling Remodeling of the Atria in Heart Failure Patients with and Without Atrial Fibrillation. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Melnyk, P.; Feng, J.; Wang, Z.; Petrecca, K.; Shrier, A.; Nattel, S. Effects of experimental heart failure on atrial cellular and ionic electrophysiology. Circulation 2000, 101, 2631–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, P.; Morton, J.B.; Davidson, N.C.; Spence, S.J.; Vohra, J.K.; Sparks, P.B.; Kalman, J.M. Electrical remodeling of the atria in congestive heart failure: Electrophysiological and electroanatomic mapping in humans. Circulation 2003, 108, 1461–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreieck, J.; Wang, Y.; Overbeck, M.; Schomig, A.; Schmitt, C. Altered transient outward current in human atrial myocytes of patients with reduced left ventricular function. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2000, 11, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Workman, A.J.; Pau, D.; Redpath, C.J.; Marshall, G.E.; Russell, J.A.; Norrie, J.; Kane, K.A.; Rankin, A.C. Atrial cellular electrophysiological changes in patients with ventricular dysfunction may predispose to AF. Heart Rhythm. 2009, 6, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C.; Wiedmann, F.; Zhou, X.B.; Heijman, J.; Voigt, N.; Ratte, A.; Lang, S.; Kallenberger, S.M.; Campana, C.; Weymann, A.; et al. Inverse remodelling of K2P3.1 K+ channel expression and action potential duration in left ventricular dysfunction and atrial fibrillation: Implications for patient-specific antiarrhythmic drug therapy. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 1764–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sridhar, A.; Nishijima, Y.; Terentyev, D.; Khan, M.; Terentyeva, R.; Hamlin, R.L.; Nakayama, T.; Gyorke, S.; Cardounel, A.J.; Carnes, C.A. Chronic heart failure and the substrate for atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009, 84, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rankin, A.C.; Workman, A.J. Duration of heart failure and the risk of atrial fibrillation: Different mechanisms at different times? Cardiovasc. Res. 2009, 84, 180–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morillo, C.A.; Klein, G.J.; Jones, D.L.; Guiraudon, C.M. Chronic rapid atrial pacing. Structural, functional, and electrophysiological characteristics of a new model of sustained atrial fibrillation. Circulation 1995, 91, 1588–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaspo, R.; Bosch, R.F.; Talajic, M.; Nattel, S. Functional mechanisms underlying tachycardia-induced sustained atrial fibrillation in a chronic dog model. Circulation 1997, 96, 4027–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, L.; Feng, J.; Gaspo, R.; Li, G.R.; Wang, Z.; Nattel, S. Ionic remodeling underlying action potential changes in a canine model of atrial fibrillation. Circ. Res. 1997, 81, 512–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, L.; Melnyk, P.; Gaspo, R.; Wang, Z.; Nattel, S. Molecular mechanisms underlying ionic remodeling in a dog model of atrial fibrillation. Circ. Res. 1999, 84, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, J.R.; Cha, T.J.; Zhang, L.; Chartier, D.; Villeneuve, L.; Hebert, T.E.; Nattel, S. Characterization of a hyperpolarization-activated time-dependent potassium current in canine cardiomyocytes from pulmonary vein myocardial sleeves and left atrium. J. Physiol. 2004, 557, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinanian, S.; Boixel, C.; Juin, C.; Hulot, J.S.; Coulombe, A.; Rucker-Martin, C.; Bonnet, N.; Le Grand, B.; Slama, M.; Mercadier, J.J.; et al. Downregulation of the calcium current in human right atrial myocytes from patients in sinus rhythm but with a high risk of atrial fibrillation. Eur. Heart J. 2008, 29, 1190–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Grand, B.L.; Hatem, S.; Deroubaix, E.; Couetil, J.P.; Coraboeuf, E. Depressed transient outward and calcium currents in dilated human atria. Cardiovasc. Res. 1994, 28, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberger, J.J.; Cain, M.E.; Hohnloser, S.H.; Kadish, A.H.; Knight, B.P.; Lauer, M.S.; Maron, B.J.; Page, R.L.; Passman, R.S.; Siscovick, D.; et al. American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation/Heart Rhythm Society scientific statement on noninvasive risk stratification techniques for identifying patients at risk for sudden cardiac death: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology Committee on Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation 2008, 118, 1497–1518. [Google Scholar]

- Bardy, G.H.; Lee, K.L.; Mark, D.B.; Poole, J.E.; Packer, D.L.; Boineau, R.; Domanski, M.; Troutman, C.; Anderson, J.; Johnson, G.; et al. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zannad, F.; McMurray, J.J.; Krum, H.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Swedberg, K.; Shi, H.; Vincent, J.; Pocock, S.J.; Pitt, B.; Group, E.-H.S. Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stecker, E.C.; Vickers, C.; Waltz, J.; Socoteanu, C.; John, B.T.; Mariani, R.; McAnulty, J.H.; Gunson, K.; Jui, J.; Chugh, S.S. Population-based analysis of sudden cardiac death with and without left ventricular systolic dysfunction: Two-year findings from the Oregon Sudden Unexpected Death Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 47, 1161–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, D.S.; Jackson, L.E.; Smith, J.M.; Garan, H.; Ruskin, J.N.; Cohen, R.J. Electrical alternans and vulnerability to ventricular arrhythmias. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 330, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohnloser, S.H.; Klingenheben, T.; Bloomfield, D.; Dabbous, O.; Cohen, R.J. Usefulness of microvolt T-wave alternans for prediction of ventricular tachyarrhythmic events in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy: Results from a prospective observational study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 41, 2220–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, R.D.; Kasper, E.K.; Baughman, K.L.; Marban, E.; Calkins, H.; Tomaselli, G.F. Beat-to-beat QT interval variability: Novel evidence for repolarization lability in ischemic and nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 1997, 96, 1557–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacoviello, M.; Forleo, C.; Guida, P.; Romito, R.; Sorgente, A.; Sorrentino, S.; Catucci, S.; Mastropasqua, F.; Pitzalis, M. Ventricular repolarization dynamicity provides independent prognostic information toward major arrhythmic events in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007, 50, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, P.P.; Barlow, C.; Hart, G. Prolongation of the QT interval in heart failure occurs at low but not at high heart rates. Clin. Sci. 2000, 98, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaye, K.M.; Sani, M.U. Electrocardiographic abnormalities in patients with heart failure. Cardiovasc. J. Afr. 2008, 19, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karwatowska-Prokopczuk, E.; Wang, W.; Cheng, M.L.; Zeng, D.; Schwartz, P.J.; Belardinelli, L. The risk of sudden cardiac death in patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome and prolonged QTc interval: Effect of ranolazine. Europace 2013, 15, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hondeghem, L.M.; Carlsson, L.; Duker, G. Instability and triangulation of the action potential predict serious proarrhythmia, but action potential duration prolongation is antiarrhythmic. Circulation 2001, 103, 2004–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belardinelli, L.; Antzelevitch, C.; Vos, M.A. Assessing predictors of drug-induced torsade de pointes. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2003, 24, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomsen, M.B.; Verduyn, S.C.; Stengl, M.; Beekman, J.D.; de Pater, G.; van Opstal, J.; Volders, P.G.; Vos, M.A. Increased short-term variability of repolarization predicts d-sotalol-induced torsades de pointes in dogs. Circulation 2004, 110, 2453–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, C.L.; Pollard, C.E.; Hammond, T.G.; Valentin, J.P. Nonclinical proarrhythmia models: Predicting Torsades de Pointes. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 2005, 52, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, M.E. QT interval prolongation and arrhythmia: An unbreakable connection? J. Intern. Med. 2006, 259, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antzelevitch, C.; Sicouri, S.; Di Diego, J.M.; Burashnikov, A.; Viskin, S.; Shimizu, W.; Yan, G.X.; Kowey, P.; Zhang, L. Does Tpeak-Tend provide an index of transmural dispersion of repolarization? Heart Rhythm. 2007, 4, 1114–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, D.P.; Saad, M.N.; Shams, O.F.; Owen, J.S.; Xue, J.Q.; Abi-Samra, F.M.; Khatib, S.; Nelson-Twakor, O.S.; Milani, R.V. Relationships between the T-peak to T-end interval, ventricular tachyarrhythmia, and death in left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Europace 2012, 14, 1172–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, T.M.; Stahls, P.F., 3rd; Abi Samra, F.M.; Bernard, M.L.; Khatib, S.; Polin, G.M.; Xue, J.Q.; Morin, D.P. T-peak to T-end interval for prediction of ventricular tachyarrhythmia and mortality in a primary prevention population with systolic cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2015, 12, 1789–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbhaiya, C.; Po, J.R.; Hanon, S.; Schweitzer, P. Tpeak-Tend and Tpeak-Tend/QT ratio as markers of ventricular arrhythmia risk in cardiac resynchronization therapy patients. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2013, 36, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roden, D.M. Taking the “idio” out of “idiosyncratic”: Predicting torsades de pointes. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 1998, 21, 1029–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varro, A.; Balati, B.; Iost, N.; Takacs, J.; Virag, L.; Lathrop, D.A.; Csaba, L.; Talosi, L.; Papp, J.G. The role of the delayed rectifier component IKs in dog ventricular muscle and Purkinje fibre repolarization. J. Physiol. 2000, 523 Pt 1, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roden, D.M.; Yang, T. Protecting the heart against arrhythmias: Potassium current physiology and repolarization reserve. Circulation 2005, 112, 1376–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jost, N.; Virag, L.; Bitay, M.; Takacs, J.; Lengyel, C.; Biliczki, P.; Nagy, Z.; Bogats, G.; Lathrop, D.A.; Papp, J.G.; et al. Restricting excessive cardiac action potential and QT prolongation: A vital role for IKs in human ventricular muscle. Circulation 2005, 112, 1392–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, R.D. QT variability. J. Electrocardiol. 2003, 36 (Suppl. 1), 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkevisser, R.; Wijers, S.C.; van der Heyden, M.A.; Beekman, J.D.; Meine, M.; Vos, M.A. Beat-to-beat variability of repolarization as a new biomarker for proarrhythmia in vivo. Heart Rhythm. 2012, 9, 1718–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Opstal, J.M.; Schoenmakers, M.; Verduyn, S.C.; de Groot, S.H.; Leunissen, J.D.; van Der Hulst, F.F.; Molenschot, M.M.; Wellens, H.J.; Vos, M.A. Chronic amiodarone evokes no torsade de pointes arrhythmias despite QT lengthening in an animal model of acquired long-QT syndrome. Circulation 2001, 104, 2722–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, M.B.; Truin, M.; van Opstal, J.M.; Beekman, J.D.; Volders, P.G.; Stengl, M.; Vos, M.A. Sudden cardiac death in dogs with remodeled hearts is associated with larger beat-to-beat variability of repolarization. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2005, 100, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengyel, C.; Varro, A.; Tabori, K.; Papp, J.G.; Baczko, I. Combined pharmacological block of I(Kr) and I(Ks) increases short-term QT interval variability and provokes torsades de pointes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 151, 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husti, Z.; Tabori, K.; Juhasz, V.; Hornyik, T.; Varro, A.; Baczko, I. Combined inhibition of key potassium currents has different effects on cardiac repolarization reserve and arrhythmia susceptibility in dogs and rabbits. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2015, 93, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinterseer, M.; Thomsen, M.B.; Beckmann, B.M.; Pfeufer, A.; Schimpf, R.; Wichmann, H.E.; Steinbeck, G.; Vos, M.A.; Kaab, S. Beat-to-beat variability of QT intervals is increased in patients with drug-induced long-QT syndrome: A case control pilot study. Eur. Heart J. 2008, 29, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinterseer, M.; Beckmann, B.M.; Thomsen, M.B.; Pfeufer, A.; Dalla Pozza, R.; Loeff, M.; Netz, H.; Steinbeck, G.; Vos, M.A.; Kaab, S. Relation of increased short-term variability of QT interval to congenital long-QT syndrome. Am. J. Cardiol. 2009, 103, 1244–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinterseer, M.; Beckmann, B.M.; Thomsen, M.B.; Pfeufer, A.; Ulbrich, M.; Sinner, M.F.; Perz, S.; Wichmann, H.E.; Lengyel, C.; Schimpf, R.; et al. Usefulness of short-term variability of QT intervals as a predictor for electrical remodeling and proarrhythmia in patients with nonischemic heart failure. Am. J. Cardiol. 2010, 106, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oosterhoff, P.; Tereshchenko, L.G.; van der Heyden, M.A.; Ghanem, R.N.; Fetics, B.J.; Berger, R.D.; Vos, M.A. Short-term variability of repolarization predicts ventricular tachycardia and sudden cardiac death in patients with structural heart disease: A comparison with QT variability index. Heart Rhythm. 2011, 8, 1584–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orosz, A.; Baczko, I.; Nagy, V.; Gavaller, H.; Csanady, M.; Forster, T.; Papp, J.G.; Varro, A.; Lengyel, C.; Sepp, R. Short-term beat-to-beat variability of the QT interval is increased and correlates with parameters of left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2015, 93, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Current | Change | References |

|---|---|---|

| INa peak | ↓ | [25] |

| INaL | ↑ | [61,64,70] |

| ICaL |  | [11,154,155] |

| Ito | ↓ | [21,34,35,36] |

| IK1 | ↓ | [12,17,19] |

| IKr | ↓ | [12,19,34] |

| IKs | ↓ | [12,17,19,21] |

| IKCa (SK2) | ↑ | [79,80,81,82] |

| If | ↑ | [164,165,167] |

| INCX | ↑ | [20,71] |

| Connexin | ↓ | [96,160] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Husti, Z.; Varró, A.; Baczkó, I. Arrhythmogenic Remodeling in the Failing Heart. Cells 2021, 10, 3203. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10113203

Husti Z, Varró A, Baczkó I. Arrhythmogenic Remodeling in the Failing Heart. Cells. 2021; 10(11):3203. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10113203

Chicago/Turabian StyleHusti, Zoltán, András Varró, and István Baczkó. 2021. "Arrhythmogenic Remodeling in the Failing Heart" Cells 10, no. 11: 3203. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10113203

APA StyleHusti, Z., Varró, A., & Baczkó, I. (2021). Arrhythmogenic Remodeling in the Failing Heart. Cells, 10(11), 3203. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10113203