Enhancing Cereal Crop Tolerance to Low-Phosphorus Conditions Through Fertilisation Strategies: The Role of Silicon in Mitigating Phosphate Deficiency

Abstract

1. Introduction

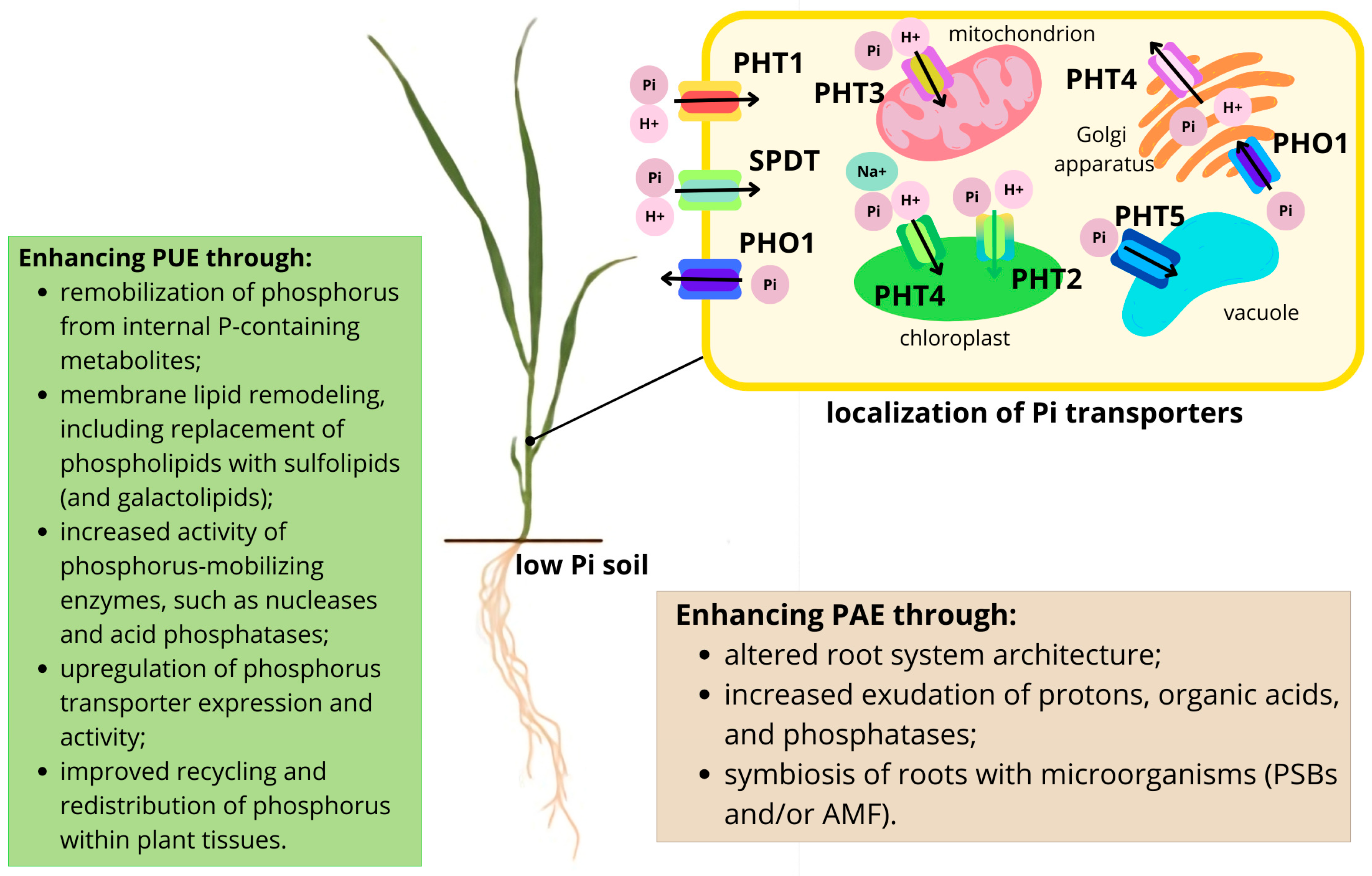

2. Intracellular and Long-Distance Phosphate Transport in Plants

3. Physiological and Molecular Responses of Plants to Pi Deficiency

3.1. Plant Strategies to Improve the Efficiency of Phosphorus Acquisition

3.2. Mechanisms and Approaches to Enhance P Use Efficiency by Plants

3.3. Genetic Modifications Introduced by Researchers—For Better P Uptake and P Management in Crop Plants

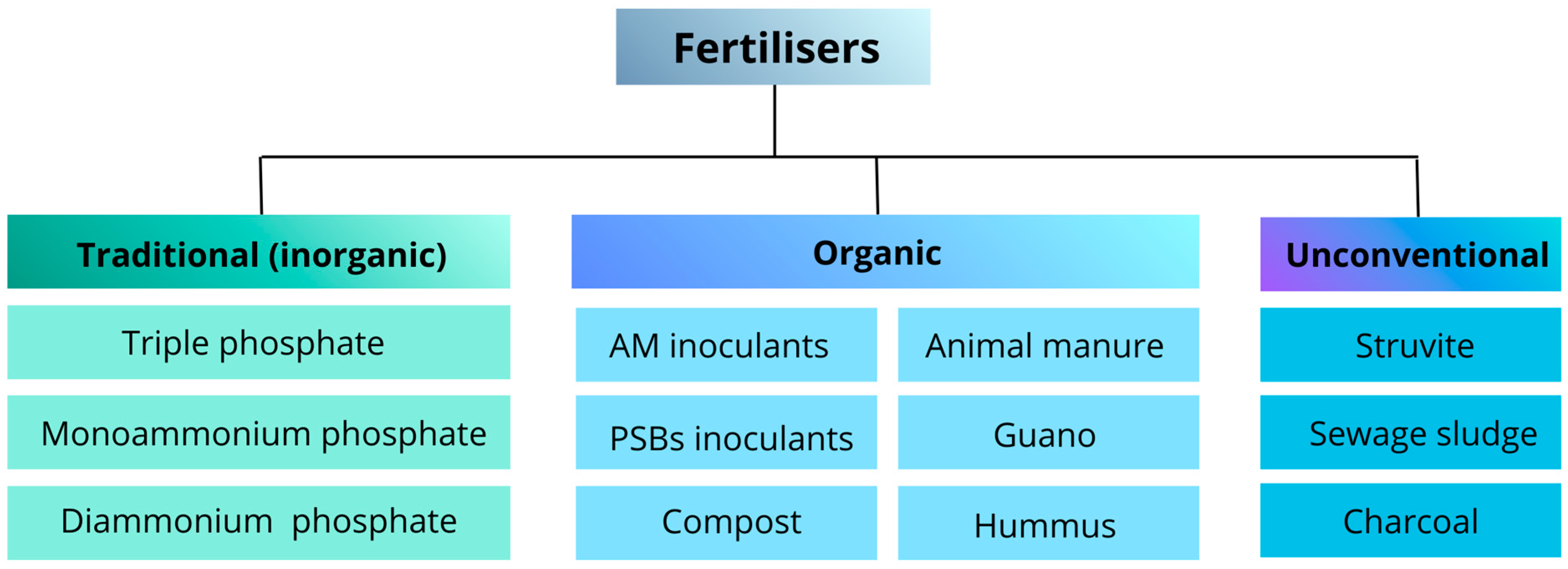

4. Modern Fertilisation Strategies for Sustainable Phosphorus Management in Agriculture

4.1. Organic Amendments in Modern Crop Management

4.2. Role of Microbial Fertilisers in Sustainable Crop Production

4.3. Alternative Sources of Plant-Available Phosphorus

4.4. Techniques for Targeted Nutrient Delivery

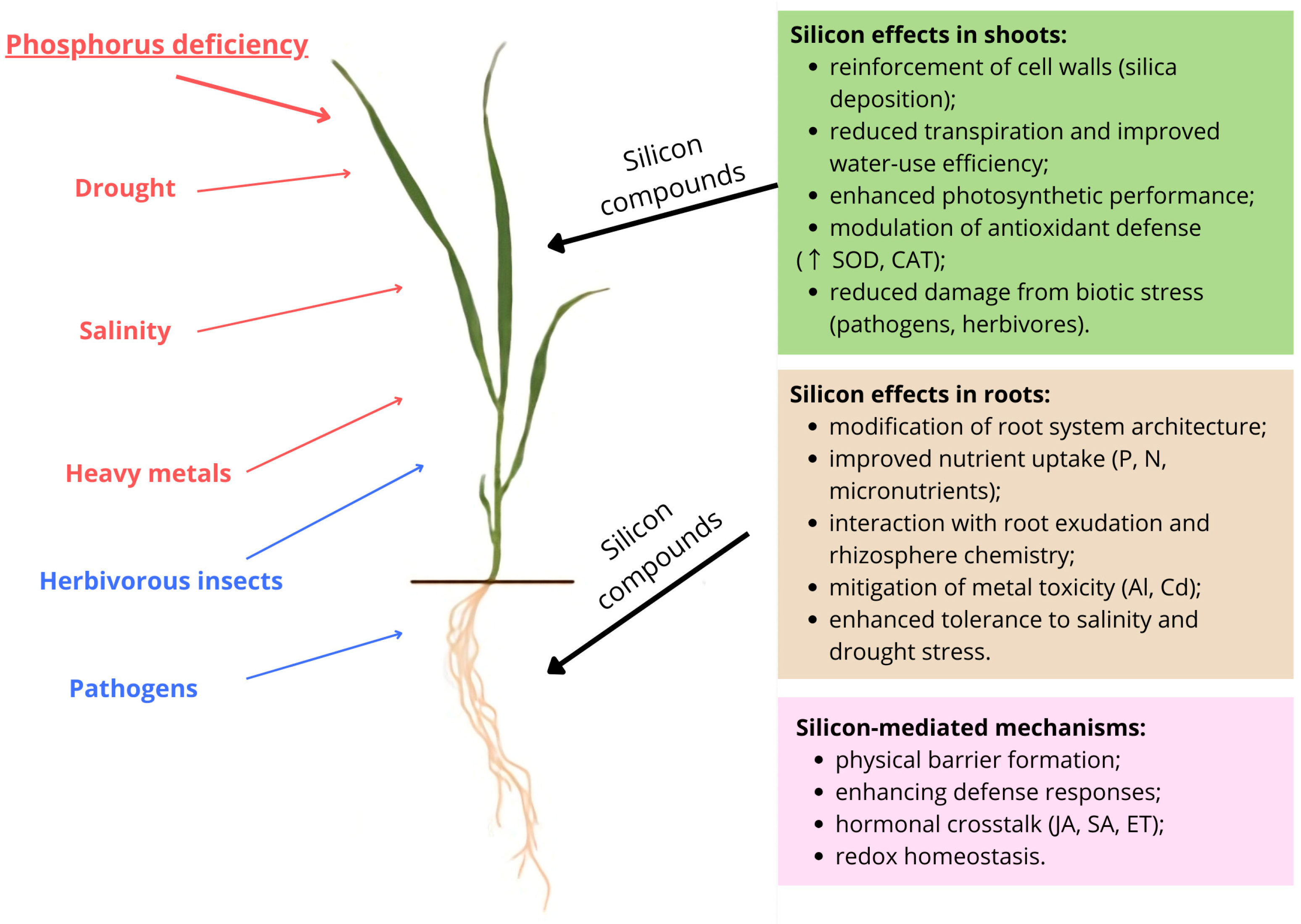

5. The Role of Silicon in Alleviating Phosphorus Deficiency

| Silicon Compound/ Treatment/ Concentration | Plant Species (Organ) | Pi Deficiency/ Stress Severity | The Effect of Si on Plant Cells/Rhizosphere | Improved Plants Functioning Under Low Pi | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium silicate (K2SiO3 nH2O) (1.5 mM) | Solanum lycopersicum (cv. Zhong Za “No. 9”)—(roots, leaves, stems) | Early P deficiency (1–2 weeks), low P(P 0.44 mM + Si 1.5 mM) | Si decreased ROS and malondialdehyde levels via increasing antioxidant enzyme activity (superoxide dismutase, peroxidase, catalase). | Si compensated P deficiency effects: increasing photosynthesis, antioxidant potential, nutrient content/homeostasis (K, Na, Ca, Mg, Fe, Mn). | [176] |

| Sodium metasilicate (10 μM) | Hordeum vulgare (roots) | Short-term Pi deficiency (7 days) | Auxin and NO participated in Si-mediated root elongation and Pi-transporter expression (HvPHT1). | Increased Pi uptake by barley and improved root growth. | [185] |

| Silicic acid (0 and 120 mg Si kg−1) | Oryza sativa (seedlings, roots, rhizosphere) | Low P soils, 45-day cultivation period | Si increases the dissolution of Fe–P complexes and expands acid phosphatase hotspots in the rhizosphere. | The Si application increased acid phosphatase activity and seedling biomass. Si-induced changes in root architecture, including increases in maximum vertical extension and root angle. | [159] |

| Sodium silicate (Na2SiO3, 400 mg Si kg−1 dry soil) | Triticum aestivum (cv. Pobeda) (roots and shoots, root exudates) | Low P acidic soil (4 weeks after germination) | Increased root exudation of organic acids (malate, citrate) mobilises Pi in the rhizosphere. High expression of Pi transporters (TaPHT1.1 and TaPHT1.2). | The Si application increased wheat biomass and shoot P concentration, comparable to that of P-fertilised plants. | [162] |

| Na2SiO3 (1.5 mM in hydroponics) | Triticum aestivum (cv. Rubisko) (shoots and roots) | Low Pi (30 days) (0 or 0.2 mM KH2PO4) | Results demonstrated that Si promote P recycling from P-metabolites in P-deprived wheat. | Wheat plants grown without external P but supplemented with Si showed high P levels. | [186] |

| Silicon fertiliser (0 or 45 kg·ha−1) | Oryza sativa (cv. Suigeng 18) (roots, exudation, rhizosphere, leaves) | Low Pi (45 days) (0, 25 and 75 P2O5 kg ha−1) (water-saving rice cultivation) | Increased organic acid content (malate, succinate), enhanced acid phosphatase activity; reduced ATPase content. | Increased P content promoted shoot growth (downregulation of SUT1, SWEET11, CIN2). Upregulation of OsPT2, OsPT4, and OsPT8 in roots leads to improved Pi uptake. | [160] |

| Silica gel —as Si fertiliser (2 or 4 g kg−1 Si) | Oryza sativa (cv. Haenuki) (high-density nursery seedlings) | Dicalcium superphosphate—P fertiliser (0 or 60 mg kg−1 P) | Si treatment stabilised early rice growth after transplanting seedlings to new culture conditions. | P and Si application stabilised rice growth under transplanting stress. | [187] |

| Silicic acid [Si(OH)4] Si application (0, 50, 100, 200 and 400 mg kg−1 soil) | Avena sativa (cv. Faikbey) (shoot, leaves, roots) | P level in the soil (0, 10, 25, 50, 100 mg P kg−1 soil) | Si treatment had beneficial effects on oat shoot dry mass, P content, and P uptake by oat plants. | The Si application to moderately acidic soils can be a method for the reduction in P deficiency stress as well as P toxicity in oats (by decreasing excess P absorption). | [188] |

| Sodium silicate (stabilised with sorbitol) | Urochloa brizantha cv. Marandu and Megathyrsus maximum cv. Massai | Multi-nutrient deficiency, including low-P stress | Beneficial effects of Si in stressed and non-stressed plants. | The Si application increased the content of phenolic compounds, the quantum efficiency of photosystem II, the efficiency of P use, and shoot dry mass production. | [189] |

| Si nanoparticles (8.5–9.7 nm) (2 mM Si) | Capsicum annuum bell pepper (shoot, leaves, roots) | Severe P deficiency (up to 54 days after transplanting) | Si increased the antioxidant content (ascorbic acid, phenolics, carotenoids), photosynthetic apparatus efficiency and plant growth. Si enhances plant yield and health. | Si overcame nutrient deficiencies. The key role of silicon (Si) is to mitigate the effects of P deficiency while providing benefits to plants that require sufficient phosphorus. | [28] |

| Si (0 or 14.36 kg H4SiO4 ha−1 year−1) | Carex myosuroides Poa pratensis (alpine grassland) (leaves, soil samples) | Low P soil (0, 49, 98, 148 kg P ha−1 year−1) | In addition, reduced lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose contents in grass leaves. | Si optimised structural carbon compounds, enhanced P and N uptake efficiency, and increased grass biomass production. | [190] |

| Silicic acid (344 g kg−1 total Si) | Oryza sativa (inoculated with Rhizophagus irregularis) (rice leaves and stems, soil samples) | Low P and high P availability (18 and 62 mg P kg−1) | Si plays various roles in regulating AMF functioning and P content in leaves, as dependent on soil P levels. | Under low P conditions, Si reduced arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) colonisation. Under high P availability, the combination of Si and AMF increased stem P content. | [191] |

| Potassium silicate (K2O3Si, 3 or 6 mL L−1) | Zea mays (cv. Yaqout) (leaves, corn cobs, grains) | Low P (up to 60 days after sowing) + AMF (Glomus spp.) | Si foliar application enhanced chlorophyll content, increased grain yield, and quality | Si and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) reduced the adverse effects of salinity on maize under low P conditions. | [192] |

| Three Si treatments: Silicic acid (1 mmol/L), organosilicon, Nano-silicon (1 mmol/L) | Oryza sativa (14 varieties of rice) (shoot, leaves, roots) | Lower P conditions—rice plants grown for 21 days | Si affects the assembly of cell wall components, thus affecting P adsorption. Inorganic silicon and Nano-silicon altered the P adsorption of cell walls. | Inorganic Si is the best among the 3 Si materials for improving rice growth. Si treatments changed the distribution of P in rice. | [193] |

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tan, Y.; Ning, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, F.; Cao, X.; Wang, Q.; Ren, A. Multilayered Regulation of Fungal Phosphate Metabolism: From Molecular Mechanisms to Ecological Roles in the Global Phosphorus Cycle. Life 2025, 15, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; Lin, R.; Wang, Z.; Mao, C. Molecular Mechanisms and Genetic Improvement of Low-phosphorus Tolerance in Rice. Plant Cell Environ. 2022, 46, 1104–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.Y.; Lin, W.Y.; Hsiao, Y.M.; Chiou, T.J. Milestones in Understanding Transport, Sensing, and Signaling of the Plant Nutrient Phosphorus. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 1504–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solangi, F.; Zhu, X.; Khan, S.; Rais, N.; Majeed, A.; Sabir, D.-M.; Iqbal, R.; Ali, S.; Hafeez, A.; Ali, B.; et al. The Global Dilemma of Soil Legacy Phosphorus and Its Improvement Strategies under Recent Changes in Agro-Ecosystem Sustainability. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 23271–23282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, S.; Shi, S.; Obaid, H.; Dong, X.; He, X. Differential Effects of Nitrogen and Phosphorus Fertilization Rates and Fertilizer Placement Methods on P Accumulations in Maize. Plants 2024, 13, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.; Li, B.; Cao, E.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Sun, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Ma, C. Optimizing Nitrogen and Phosphorus Fertilizer Application for Wheat Yield on Alkali Soils: Mechanisms and Effects. Agronomy 2025, 15, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Levengood, H.; Fan, J.; Zhang, C. Plants Under Stress: Exploring Physiological and Molecular Responses to Nitrogen and Phosphorus Deficiency. Plants 2024, 13, 3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, G.; Ahmadi, S.H.; Amelung, W.; Athmann, M.; Ewert, F.; Gaiser, T.; Gocke, M.I.; Kautz, T.; Postma, J.; Rachmilevitch, S.; et al. Nutrient Deficiency Effects on Root Architecture and Root-to-Shoot Ratio in Arable Crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1067498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmera, I.; Hodgman, T.C.; Lu, C. An Integrative Systems Perspective on Plant Phosphate Research. Genes 2019, 10, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, P.-S.; Chiang, C.-P.; Leong, S.J.; Chiou, T.-J. Sensing and Signaling of Phosphate Starvation: From Local to Long Distance. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 59, 1714–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayaka, S.; Ghahremani, M.; Siebers, M.; Wasaki, J.; Plaxton, W. Recent Insights into the Metabolic Adaptations of Phosphorus Deprived Plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 72, 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škarpa, P.; Školníková, M.; Antošovský, J.; Horký, P.; Smýkalová, I.; Horáček, J.; Dostálová, R.; Kozáková, Z. Response of Normal and Low-Phytate Genotypes of Pea (Pisum sativum L.) on Phosphorus Foliar Fertilization. Plants 2021, 10, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferron, L.M.E.; Van Groenigen, J.W.; Koopmans, G.F.; Vidal, A. Can Earthworms and Root Traits Improve Plant Struvite-P Uptake? A Field Mesocosm Study. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 377, 109255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinon, T.L.M. The Urgent Recognition of Phosphate Resource Scarcity and Pollution. RSC Sustain. 2023, 1, 1594–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; White, P.; Cheng, L. Mechanisms for Improving Phosphorus Utilization Efficiency in Plants: A Review. Ann. Bot. 2021, 129, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokulan, V.; Schneider, K.; Macrae, M.; Wilson, H. Struvite Application to Field Corn Decreases the Risk of Environmental Phosphorus Loss While Maintaining Crop Yield. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 366, 108936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Andreev, K.; Dupre, M. Major Trends in Population Growth Around the World. China CDC Wkly. 2021, 3, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Samota, S.R.; Venkatesh, K.; Tripathi, S. Global Trends in Use of Nano-Fertilizers for Crop Production: Advantages and Constraints—A Review. Soil Tillage Res. 2023, 228, 105645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolizadeh, A.; Labbé, C.; Sonah, H.; Deshmukh, R.K.; Belzile, F.; Menzies, J.G.; Bélanger, R.R. Silicon Protects Soybean Plants against Phytophthora Sojae by Interfering with Effector-Receptor Expression. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YAN, G.; Nikolic, M.; YE, M.; Xiao, Z.; Liang, Y. Silicon Acquisition and Accumulation in Plant and Its Significance for Agriculture. J. Integr. Agric. 2018, 17, 2138–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etesami, H.; Jeong, B.R.; Glick, B. Contribution of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi, Phosphate–Solubilizing Bacteria, and Silicon to P Uptake by Plant. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 699618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Awan, S.; Rizwan, M.; Ali, S.; Hassan, M.; Brestic, M.; Zhang, X.; Huang, L. Effects of Silicon on Heavy Metal Uptake at the Soil-Plant Interphase: A Review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 222, 112510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovic, J.; Kostic, L.; Bosnic, P.; Kirkby, E.A.; Nikolic, M. Interactions of Silicon with Essential and Beneficial Elements in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 697592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Waraich, E.; Haider, A.; Mahmood, N.; Ramzan, T.; Alamri, S.; Siddiqui, M.; Akhtar, M.S. Silicon-Mediated Improvement in Drought and Salinity Stress Tolerance of Black Gram (Vigna mungo L.) by Modulating Growth, Physiological, Biochemical, and Root Attributes. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 37231–37242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, K.; Ajaj, R.; Nazmy, A.; Ebrahim, M.; Hassan, I.; Hassan, F.; Alam-Eldein, S.; Ali, M.A.A. Silicon: A Powerful Aid for Medicinal and Aromatic Plants against Abiotic and Biotic Stresses for Sustainable Agriculture. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivera-Viciedo, D.; Oliveira, K.; Prado, R.; Habermann, E.; Martinez, C.; Zanine, A. Silicon Uptake and Utilization on Panicum Maximum Grass Modifies C:N:P Stoichiometry under Warming and Soil Water Deficit. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 235, 105884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Prado, R.; Luiz Fabiano, P.; Souza, J., Jr. The Effect of Abiotic Stresses on Plant C:N:P Homeostasis and Their Mitigation by Silicon. Crop J. 2024, 12, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Silva, B.; Alves, D.; Lima, P.; Prado, R. Silicon, by Modulating Homeostasis and Nutritional Efficiency, Increases the Antioxidant Action and Tolerance of Bell Peppers to Phosphorus Deficiency. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 343, 114093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artyszak, A. Effect of Silicon Fertilization on Crop Yield Quantity and Quality—A Literature Review in Europe. Plants 2018, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Versaw, W.K.; Garcia, L.R. Intracellular Transport and Compartmentation of Phosphate in Plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 39, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayadi, A.; David, P.; Arrighi, J.-F.; Chiarenza, S.; Thibaud, M.-C.; Nussaume, L.; Marin, E. Reducing the Genetic Redundancy of Arabidopsis PHOSPHATE TRANSPORTER1 Transporters to Study Phosphate Uptake and Signaling. Plant Physiol. 2015, 167, 1511–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Fan, H.; Gu, M.; Qu, H.; Xu, G. Phosphate Transporter OsPht1;8 in Rice Plays an Important Role in Phosphorus Redistribution from Source to Sink Organs and Allocation between Embryo and Endosperm of Seeds. Plant Sci. 2015, 230, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae, A.L.; Cybinski, D.H.; Jarmey, J.M.; Smith, F.W. Characterization of Two Phosphate Transporters from Barley; Evidence for Diverse Function and Kinetic Properties among Members of the Pht1 Family. Plant Mol. Biol. 2003, 53, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Miao, Q.; Sun, D.; Yang, G.; Wu, C.-A.; Huang, J.; Zheng, C. The Mitochondrial Phosphate Transporters Modulate Plant Responses to Salt Stress via Affecting ATP and Gibberellin Metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyaji, T.; Kuromori, T.; Takeuchi, Y.; Yamaji, N.; Yokosho, K.; Shimazawa, A.; Sugimoto, E.; Omote, H.; Shinozaki, K.; Moriyama, Y. AtPHT4;4 Is a Chloroplast-Localized Ascorbate Transporter in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, P.; Herdean, A.; Adolfsson, L.; Beebo, A.; Nziengui, H.; Irigoyen, S.; Unnep, R.; Zsiros, O.; Nagy, G.; Garab, G.; et al. The Arabidopsis Thylakoid Transporter PHT4;1 Influences Phosphate Availability for ATP Synthesis and Plant Growth. Plant J. 2015, 84, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Yan, Y.; Yang, X.; Xie, M.; Hu, Z.; Shen, X.; Ai, H.; Lin, H.; et al. Mutation of the Chloroplast-Localized Phosphate Transporter OsPHT2;1 Reduces Flavonoid Accumulation and UV Tolerance in Rice. Plant J. 2020, 102, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.-Y.; Huang, T.-K.; Kuo, H.-F.; Chiou, T.-J. Role of Vacuoles in Phosphorus Storage and Remobilization. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 3045–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhao, H.; Wan, R.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Tian, W.; Wenyuan, R.; Wang, F.; Deng, M.; Wang, J.; et al. Identification of Vacuolar Phosphate Efflux Transporters in Land Plants. Nat. Plants 2019, 5, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, M.; Zhao, F.; Sun, G.; Xu, M.; Fu, A.; Lan, W.; Luan, S. A SPX Domain Vacuolar Transporter Links Phosphate Sensing to Homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 1590–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, R.; Grob, H.; Weder, B.; Green, P.; Klein, M.; Frelet-Barrand, A.; Schjoerring, J.; Brearley, C.; Martinoia, E. The Arabidopsis ATP-Binding Cassette Protein AtMRP5/AtABCC5 Is a High Affinity Inositol Hexakisphosphate Transporter Involved in Guard Cell Signaling and Phytate Storage. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 33614–33622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.; Ma, G.; Sui, L.; Wei, M.; Satheesh, V.; Zhang, R.; Ge, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, T.-E.; Wittwer, C.; et al. Inositol Pyrophosphate InsP8 Acts as an Intracellular Phosphate Signal in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2019, 12, 1463–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zuo, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, R.; Savarin, J.; Broger, L.; Cheng, P.; Wang, Q.; et al. Mechanistic Insights into the Regulation of Plant Phosphate Homeostasis by the Rice SPX2—PHR2 Complex. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Hu, Q.; Xiao, X.; Yao, D.; Ge, S.; Ye, J.; Li, H.; Cai, R.; Liu, R.; Meng, F.; et al. Mechanism of Phosphate Sensing and Signaling Revealed by Rice SPX1-PHR2 Complex Structure. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 7040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ried, M.; Wild, R.; Zhu, J.; Pipercevic, J.; Sturm, K.; Broger, L.; Harmel, R.; Abriata, L.; Hothorn, L.; Fiedler, D.; et al. Inositol Pyrophosphates Promote the Interaction of SPX Domains with the Coiled-Coil Motif of PHR Transcription Factors to Regulate Plant Phosphate Homeostasis. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaji, N.; Takemoto, Y.; Miyaji, T.; Mitani-Ueno, N.; Yoshida, K.T.; Ma, J.F. Reducing Phosphorus Accumulation in Rice Grains with an Impaired Transporter in the Node. Nature 2017, 541, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiańska, I.; Bucher, M.; Häusler, R. Intracellular Phosphate Homeostasis—A Short Way from Metabolism to Signaling. Plant Sci. 2019, 286, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyota, K.; Tamura, M.; Ohdan, T.; Nakamura, Y. Expression Profiling of Starch Metabolism-Related Plastidic Translocator Genes in Rice. Planta 2006, 223, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammerer, B.; Fischer, K.; Hilpert, B.; Schubert, S.; Gutensohn, M.; Weber, A.; Flügge, U.-I. Molecular Characterization of a Carbon Transporter in Plastids from Heterotrophic Tissues: The Glucose 6-Phosphate/Phosphate Antiporter. Plant Cell 1998, 10, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lambers, H. Root-Released Organic Anions in Response to Low Phosphorus Availability: Recent Progress, Challenges and Future Perspectives. Plant Soil 2020, 447, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhu, X.; Yuan, P.; Bei, H.; Wu, T.; Din, I.; Wang, C.; Hammond, J.; Wang, S.; Ding, G.; et al. Root Morphological Adaptation and Leaf Lipid Remobilization Drive Differences in Phosphorus Use Efficiency in Rapeseed Seedlings. Crop J. 2025, 13, 524–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shi, N.; Fan, J.; Wang, F.; George, T.S.; Feng, G. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Stimulate Organic Phosphate Mobilization Associated with Changing Bacterial Community Structure under Field Conditions. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 20, 2639–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, C.; Pacurar, D.; Perrone, I. Adventitious Roots and Lateral Roots: Similarities and Differences. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2014, 65, 639–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orman-Ligeza, B.; Parizot, B.; Gantet, P.; Beeckman, T.; Bennett, M.; Draye, X. Post-Embryonic Root Organogenesis in Cereals: Branching out from Model Plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2013, 18, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; Ren, M.; Lin, R.; Jin, K.; Mao, C. Developmental Responses of Roots to Limited Phosphate Availability: Research Progress and Application in Cereals. Plant Physiol. 2024, 196, 2162–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.P. Harnessing Root Architecture to Address Global Challenges. Plant J. 2022, 109, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Zhang, D. The Plasticity of Root Systems in Response to External Phosphate. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żebrowska, E.; Milewska, M.; Ciereszko, I. Mechanisms of Oat (Avena sativa L.) Acclimation to Phosphate Deficiency. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xu, C.; Li, K.; Yan, S.; Qu, X.; Zhang, J. Phosphate Starvation of Maize Inhibits Lateral Root Formation and Alters Gene Expression in the Lateral Root Primordium Zone. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, P.; Urfan, M.; Sharma, S.; Hakla, H.R.; Nandan, B.; Das, R.; Roychowdhury, R.; Chowdhary, S.P. Natural Variation in Root Traits Identifies Significant SNPs and Candidate Genes for Phosphate Deficiency Tolerance in Zea mays L. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Ma, P.; Nie, Z.; Zhang, X.; He, X.; Ding, X.; Feng, X.; Lu, Q.; Ren, Z.; Lin, H.; et al. Metabolite Profiling and Genome-Wide Association Studies Reveal Response Mechanisms of Phosphorus Deficiency in Maize Seedling. Plant J. 2019, 97, 947–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Li, H.; Shen, Q.; Tang, X.; Xiong, C.; Li, H.; Pang, J.; Ryan, M.; Lambers, H.; Shen, J. Tradeoffs among Root Morphology, Exudation and Mycorrhizal Symbioses for Phosphorus-acquisition Strategies of 16 Crop Species. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, P.; Miller, A.J.; Giri, J. Organic Acids: Versatile Stress-Response Roles in Plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 4038–4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaxton, W.C.; Tran, H.T. Metabolic Adaptations of Phosphate-Starved Plants. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 1006–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Liao, H. Organic Acid Anions: An Effective Defensive Weapon for Plants against Aluminum Toxicity and Phosphorus Deficiency in Acidic Soils. J. Genet. Genom. 2016, 43, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redel, Y.; Staunton, S.; Duran, P.; Gianfreda, L.; Rumpel, C.; Mora, M.L. Fertilizer P Uptake Determined by Soil P Fractionation and Phosphatase Activity. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2019, 19, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciereszko, I.; Balwicka, H.; Żebrowska, E. Acid Phosphatases Activity and Growth of Barley, Oat, Rye and Wheat Plants as Affected by Pi Deficiency. Open Plant Sci. J. 2017, 10, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Liao, H. The Role of Intracellular and Secreted Purple Acid Phosphatases in Plant Phosphorus Scavenging and Recycling. In Annual Plant Reviews Volume 48; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 265–287. [Google Scholar]

- Elhaissoufi, W.; Ghoulam, C.; Barakat, A.; Youssef, Z.; Adnane, B. Phosphate Bacterial Solubilization: A Key Rhizosphere Driving Force Enabling Higher P Use Efficiency and Crop Productivity. J. Adv. Res. 2021, 38, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djuuna, I.; Prabawardani, S.; Massora, M. Population Distribution of Phosphate-Solubilizing Microorganisms in Agricultural Soil. Microbes Environ. 2022, 37, ME21041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Gallego, T.; Sánchez-Castro, I.; Molina, L.; Trasar-Cepeda, C.; García-Izquierdo, C.; Ramos, J.; Segura, A. Phosphorus Acquisition by Plants: Challenges and Promising Strategies for Sustainable Agriculture in the XXI Century. Pedosphere 2024, 35, 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinsinger, P.; Herrmann, L.; Lesueur, D.; Robin, A.; Trap, J.; Waithaisong, K.; Plassard, C. Impact of Roots, Microorganisms and Microfauna on the Fate of Soil Phosphorus in the Rhizosphere. In Phosphorus Metabolism in Plants; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 375–407. [Google Scholar]

- van der Heijden, M.G.A.; Martin, F.M.; Selosse, M.-A.; Sanders, I.R. Mycorrhizal Ecology and Evolution: The Past, the Present, and the Future. New Phytol. 2015, 205, 1406–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.; Van der Heijden, M. The Mycorrhizal Symbiosis: Research Frontiers in Genomics, Ecology, and Agricultural Application. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 1486–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Hodge, A.; Feng, G. Carbon and Phosphorus Exchange May Enable Cooperation between an Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus and a Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacterium. New Phytol. 2016, 210, 1022–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igiehon, N.O.; Babalola, O.O. Biofertilizers and Sustainable Agriculture: Exploring Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 4871–4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veneklaas, E.; Lambers, H.; Bragg, J.; Finnegan, P.; Lovelock, C.; Plaxton, W.; Price, C.; Scheible, W.; Shane, M.; White, P.; et al. Opportunities for Improving Phosphorus-Use Efficiency in Crop Plants. New Phytol. 2012, 195, 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Yang, L.; Luan, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, B.; Shi, J.; Zhao, F.; Lan, W.; Luan, S. A Vacuolar Phosphate Transporter Essential for Phosphate Homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E6571–E6578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambers, H.; Finnegan, P.; Jost, R.; Plaxton, W.; Shane, M.; Stitt, M. Phosphorus Nutrition in Proteaceae and Beyond. Nat. Plants 2015, 1, 15109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambers, H.; Clode, P.; Hawkins, H.; Laliberté, E.; Oliveira, R.; Reddell, P.; Shane, M.; Stitt, M.; Weston, P. Metabolic Adaptations of the Non-Mycotrophic Proteaceae to Soils with Low Phosphorus Availability. In Phosphorus Metabolism in Plants. Annual Plant Reviews; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; Volume 48, pp. 289–336. [Google Scholar]

- Dissanayaka, S.; Plaxton, W.; Lambers, H.; Siebers, M.; Marambe, B.; Wasaki, J. Molecular Mechanisms Underpinning Phosphorus-Use Efficiency in Rice. Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 1483–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, K.; Baten, A.; Waters, D.; Pantoja, O.; Julia, C.; Wissuwa, M.; Heuer, S.; Kretzschmar, T.; Rose, T. Phosphorus Remobilization from Rice Flag Leaves during Grain Filling: An RNA-Seq Study. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2016, 15, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, P.; Pandey, B.; Giri, J. Comparative Morphophysiological Analyses and Molecular Profiling Reveal Pi-Efficient Strategies of a Traditional Rice Genotype. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 6, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, P.; Giri, J. Rice and Chickpea GDPDs Are Preferentially Influenced by Low Phosphate and CaGDPD1 Encodes an Active Glycerophosphodiester Phosphodiesterase Enzyme. Plant Cell Rep. 2016, 35, 1699–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, D.; Chen, J.; Li, T.; Zhang, X. Changes in P Accumulation, Tissue P Fractions and Acid Phosphatase Activity of Pilea Sinofasciata in Poultry Manure-Impacted Soil. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 132, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigter, K.; Plaxton, W. Molecular Mechanisms of Phosphorus Metabolism and Transport during Leaf Senescence. Plants 2015, 4, 773–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellsworth, D.; Crous, K.; Lambers, H.; Cooke, J. Phosphorus Recycling in Photorespiration Maintains High Photosynthetic Capacity in Woody Species. Plant Cell Environ. 2014, 38, 1142–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovelock, C.E.; Reef, R.; Pandolfi, J.M. Variation in Elemental Stoichiometry and RNA:DNA in Four Phyla of Benthic Organisms from Coral Reefs. Funct. Ecol. 2014, 28, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takami, T.; Ohnishi, N.; Kurita, Y.; Iwamura, S.; Ohnishi, M.; Kusaba, M.; Mimura, T.; Sakamoto, W. Organelle DNA Degradation Contributes to the Efficient Use of Phosphate in Seed Plants. Nat. Plants 2018, 4, 1044–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del-Saz, N.; Ribas-Carbo, M.; McDonald, A.; Lambers, H.; Fernie, A.; Florez-Sarasa, I. An In Vivo Perspective of the Role(s) of the Alternative Oxidase Pathway. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 23, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del-Saz, N.F.; Romero-Munar, A.; Cawthray, G.R.; Palma, F.; Aroca, R.; Baraza, E.; Florez-Sarasa, I.; Lambers, H.; Ribas-Carbó, M. Phosphorus Concentration Coordinates a Respiratory Bypass, Synthesis and Exudation of Citrate, and the Expression of High-Affinity Phosphorus Transporters in Solanum Lycopersicum. Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadikiel Mmbando, G.; Ngongolo, K. The Recent Genetic Modification Techniques for Improve Soil Conservation, Nutrient Uptake and Utilization. GM Crops Food 2024, 15, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda-Rivera, J.; Alejo-Jacuinde, G.; Najera, R.; López-Arredondo, D. Prospects of Genetics and Breeding for Low Phosphate Tolerance: An Integrated Approach from Soil to Cell. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 35, 4125–4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopriva, S.; Chu, C. Are We Ready to Improve Phosphorus Homeostasis in Rice? J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 3515–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gao, Q.; Liu, Y.; He, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J. Overexpression of Transcription Factor ZmPTF1 Improves Low Phosphate Tolerance of Maize by Regulating Carbon Metabolism and Root Growth. Planta 2011, 233, 1129–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Wang, W. Functional Validation of Maize Phosphate Transporters Using Overexpression Lines. Maize Genom. Genet. 2025, 16, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Yahaya, B.S.; Gong, Y.; He, B.; Gou, J.; He, Y.; Li, J.; Kang, Y.; Xu, J.; Wang, Q.; et al. ZmARF1 Positively Regulates Low Phosphorus Stress Tolerance via Modulating Lateral Root Development in Maize. PLoS Genet. 2024, 20, e1011135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, C. Genetic Methods to Improve Phosphorus Use Efficiency in Crops. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brye, J.; Della Lunga, D.; Brye, K. Rice Response to Struvite and Other Phosphorus Fertilizers in a Phosphorus-Deficient Soil Under Simulated Furrow-Irrigation. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 7491–7506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argus Media; International Fertilizer Association (IFA). Phosphate Rock Resources and Reserves; International Fertilizer Association (IFA): Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kataki, S.; West, H.; Clarke, M.; Baruah, D. Phosphorus Recovery as Struvite: Recent Concerns for Use of Seed, Alternative Mg Source, Nitrogen Conservation and Fertilizer Potential. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 107, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonkiewicz, J.; Łabętowicz, J. Innowacje Chemiczne w Odżywianiu Roślin Od Starożytnej Gracji i Rzymu Po Czasy Najnowsze. Praca Przeglądowa. Ann. UMCS Agric. 2017, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kit Wayne, C.; Chia, S.R.; Yen, H.-W.; Nomanbhay, S.; Ho, Y.-C.; Show, P.-L. Transformation of Biomass Waste into Sustainable Organic Fertilizers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lan, X.; Hou, H.; Ji, J.; Liu, X.; Lv, Z. Multifaceted Ability of Organic Fertilizers to Improve Crop Productivity and Abiotic Stress Tolerance: Review and Perspectives. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisuzzaman, M.; Rafii, M.; Jaafar, N.; Izan, S.; Ikbal, M.; Haque, M. Effect of Organic and Inorganic Fertilizer on the Growth and Yield Components of Traditional and Improved Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Genotypes in Malaysia. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakar, K.; Dang Xuan, T.; Noori, Z.; Aryan, S.; Gulab, G. Effects of Organic and Inorganic Fertilizer Application on Growth, Yield, and Grain Quality of Rice. Agriculture 2020, 10, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakma, R.; Ullah, H.; Sonprom, J.; Biswas, A.; Himanshu, S.; Datta, A. Effects of Silicon and Organic Manure on Growth, Fruit Yield, and Quality of Grape Tomato Under Water-Deficit Stress. Silicon 2022, 15, 763–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Wright, D.; Hussain, S.; Koutroubas, S.; Seepaul, R.; George, S.; Shahkar, A.; Naveed, M.; Khan, M.; Altaf, M.; et al. Organic Fertilizer Sources Improve the Yield and Quality Attributes of Maize (Zea mays L.) Hybrids by Improving Soil Properties and Nutrient Uptake under Drought Stress. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2023, 35, 102570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, M.; Labanya, R.; Joshi, H. Influence of Long-Term Chemical Fertilizers and Organic Manures on Soil Fertility—A Review. Univers. J. Agric. Res. 2019, 7, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Li, W.; Yang, J.; Zheng, A.; Liu, F.; Feng, X.; Sparks, D.L. Mechanism of Myo-Inositol Hexakisphosphate Sorption on Amorphous Aluminum Hydroxide: Spectroscopic Evidence for Rapid Surface Precipitation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 6735–6742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Han, R.; Cao, Y.; Turner, B.L.; Ma, L.Q. Enhancing Phytate Availability in Soils and Phytate-P Acquisition by Plants: A Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 9196–9219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinch-Pedersen, H.; Sørensen, L.D.; Holm, P.B. Engineering Crop Plants: Getting a Handle on Phosphate. Trends Plant Sci. 2002, 7, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Li, S.; Qiang, R.; Lu, E.; Cuilan, L.; Zhang, J.-J.; Gao, Q. Response of Soil Microbial Community Structure to Phosphate Fertilizer Reduction and Combinations of Microbial Fertilizer. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 899727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Xu, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, P.; Hou, X.; Yang, L.; Zhang, L. Progress in Microbial Fertilizer Regulation of Crop Growth and Soil Remediation Research. Plants 2024, 13, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, L.; Li, S.; Xie, J.; Xue, X.; Jiang, Y. Screening of Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria and Their Abilities of Phosphorus Solubilization and Wheat Growth Promotion. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhaissoufi, W.; Said, K.; Ibnyasser, A.; Ghoulam, C.; Rchiad, Z.; Youssef, Z.; Lyamlouli, K.; Adnane, B. Phosphate Solubilizing Rhizobacteria Could Have a Stronger Influence on Wheat Root Traits and Aboveground Physiology Than Rhizosphere P Solubilization. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Wang, W.; Gan, Y.; Wang, L.; Chang, X.L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, W. Growth Promotion Ability of Phosphate-solubilizing Bacteria from the Soybean Rhizosphere under Maize–Soybean Intercropping Systems. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 102, 1430–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Xie, B.; Wan, C.; Song, R.; Zhong, W.; Xin, S.; Song, K. Enhancing Soil Health and Plant Growth through Microbial Fertilizers: Mechanisms, Benefits, and Sustainable Agricultural Practices. Agronomy 2024, 14, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olle, M.; Williams, I. Effective Microorganisms and Their Influence on Vegetable Production—A Review. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2013, 88, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagyaraj, D.; Sharma, M.; Maiti, D. Phosphorus Nutrition of Crops through Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi. Curr. Sci. 2015, 108, 1288–1293. [Google Scholar]

- Sudheer, S.; Johny, L.; Srivastava, S.; Adholeya, A. The Trade-in-Trade: Multifunctionalities, Current Market and Challenges for Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungal Inoculants. Symbiosis 2023, 89, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witek-Krowiak, A.; Gorazda, K.; Szopa, D.; Trzaska, K.; Moustakas, K.; Chojnacka, K. Phosphorus Recovery from Wastewater and Bio-Based Waste: An Overview. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 13474–13506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weeks, J.J., Jr.; Hettiarachchi, G.M. A Review of the Latest in Phosphorus Fertilizer Technology: Possibilities and Pragmatism. J. Environ. Qual. 2019, 48, 1300–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everaert, M.; da Silva, R.; Degryse, F.; McLaughlin, M.; Smolders, E. Limited Dissolved Phosphorus Runoff Losses from Layered Double Hydroxide and Struvite Fertilizers in a Rainfall Simulation Study. J. Environ. Qual. 2018, 47, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jama-Rodzeńska, A. The Effect of Phosgreen Fertilization on the Growth and Phosphorus Uptake of Lettuce (Lactuca sativa). Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2022, 27, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; Carreira, G.; Mota, M.; Gando-Ferreira, L.; Quina, M.; Alvarenga, P. Greenhouse Evaluation of the Agronomic Potential of Urban Wastewater-Based Fertilizers: Sewage Sludge and Struvite for Lettuce Production in Sandy Soil. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wei, B.; Wu, D.; Sun, K.; Jiao, J.; Zhang, W. The Effects of Struvite on Biomass and Soil Phosphorus Availability and Uptake in Chinese Cabbage, Cowpea, and Maize. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neofytou, G.; Chrysargyris, A.; Antoniou, M.G.; Tzortzakis, N. Radish and Spinach Seedling Production and Early Growth in Response to Struvite Use as a Phosphorus Source. Plants 2024, 13, 2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiessen Martens, J.; Entz, M.; Schneider, K.; Zvomuya, F.; Wilson, H. Response of Organic Grain and Forage Crops to Struvite Application in an Alkaline Soil. Agron. J. 2021, 114, 795–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcas-Pilz, V.; Parada, F.; Rufí-Salis, M.; Stringari, G.; González, R.; Villalba, G.; Gabarrell, X. Extended Use and Optimization of Struvite in Hydroponic Cultivation Systems. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 179, 106130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Someus, E.; Pugliese, M. Concentrated Phosphorus Recovery from Food Grade Animal Bones. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staroń, P.; Kowalski, Z.; Staroń, A.; Seidlerová, J.; Banach, M. Residues from the Thermal Conversion of Waste from the Meat Industry as a Source of Valuable Macro- and Micronutrients. Waste Manag. 2016, 49, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakweya, T.; Nigussie, A.; Worku, G.; Biresaw, A.; Aticho, A.; Hirko, O.; Ambaw, G.; Mamuye, M.; Dume, B.; Ahmed, M. Long-Term Effects of Bone Char and Lignocellulosic Biochar-Based Soil Amendments on Phosphorus Adsorption–Desorption and Crop Yield in Low-Input Acidic Soils. Soil Use Manag. 2022, 38, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwetsloot, M.; Lehmann, J.; Bauerle, T.; Vanek, S.; Hestrin, R.; Nigussie, A. Phosphorus Availability from Bone Char in a P-Fixing Soil Influenced by Root-Mycorrhizae-Biochar Interactions. Plant Soil 2016, 408, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.E.-E.A.Z. Using Bone Char as a Renewable Resource of Phosphate Fertilizers in Sustainable Agriculture and Its Effects on Phosphorus Transformations and Remediation of Contaminated Soils as Well as the Growth of Plants. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 6980–6998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayade, R.; Ghimire, A.; Khan, W.; Lay, L.; Attipoe, J.Q.; Kim, Y. Silicon as a Smart Fertilizer for Sustainability and Crop Improvement. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Xue, L.; Hou, P.; Hao, T.; Xue, L.; Zhang, X.; Sun, T.; Lobanov, S.; Yang, L. Struvite as P Fertilizer on Yield, Nutrient Uptake and Soil Nutrient Status in the Rice–Wheat Rotation System: A Two-Year Field Observation. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Pang, J.; Mickan, B.S.; Ryan, M.H.; Jenkins, S.N.; Siddique, K.H.M. Wastewater-Derived Struvite Has the Potential to Substitute for Soluble Phosphorus Fertiliser for Growth of Chickpea and Wheat. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 3011–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebers, N.; Godlinski, F.; Leinweber, P. Bone Char as Phosphorus Fertilizer Involved in Cadmium Immobilization in Lettuce, Wheat, and Potato Cropping. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2014, 177, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panten, K.; Leinweber, P. Agronomic Evaluation of Bone Char as Phosphorus Fertiliser after Five Years of Consecutive Application. J. Kult. 2020, 72, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artyszak, A.; Gozdowski, D.; Jonczak, J.; Pągowski, K.; Popielec, R.; Ahmad, Z. Yield and Quality of Maize Grain in Response to Soil Fertilization with Silicon, Calcium, Magnesium, and Manganese and the Foliar Application of Silicon and Calcium: Preliminary Results. Agronomy 2025, 15, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Han, Y.; Cui, C.; Chen, P.; Tu, N.; Rang, Z.; Yi, Z. Silicon–Calcium Fertilizer Increased Rice Yield and Quality by Improving Soil Health. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, I.; Kowalczyk, M.; Mołdoch, J.; Pawelec, S.; Radzikowski, P.; Feledyn-Szewczyk, B. The Effects of a Cultivar and Silicon Treatments on Grain Parameters and Bioactive Compound Content in Organic Spring Wheat. Foods 2025, 14, 2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görlach, B.M.; Mühling, K.H. Phosphate Foliar Application Increases Biomass and P Concentration in P Deficient Maize. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2021, 184, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Liu, C.; Huang, M.; Liu, K.; Yan, D. Effects of Foliar Fertilization: A Review of Current Status and Future Perspectives. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2021, 21, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsic, M.; Persson, D.P.; Schjoerring, J.K.; Thygesen, L.G.; Lombi, E.; Doolette, C.L.; Husted, S. Foliar-Applied Manganese and Phosphorus in Deficient Barley: Linking Absorption Pathways and Leaf Nutrient Status. Physiol. Plant. 2022, 174, e13761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.K.; Bell, R.W.; Salahin, N.; Pathan, S.; Mondol, A.T.M.A.I.; Alam, M.J.; Rashid, M.H.; Paul, P.L.C.; Hossain, M.I.; Shil, N.C. Banding of Fertilizer Improves Phosphorus Acquisition and Yield of Zero Tillage Maize by Concentrating Phosphorus in Surface Soil. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harish, M.N.; Choudhary, A.K.; Kumar, S.; Dass, A.; Singh, V.K.; Sharma, V.K.; Varatharajan, T.; Dhillon, M.K.; Sangwan, S.; Dua, V.K.; et al. Double Zero Tillage and Foliar Phosphorus Fertilization Coupled with Microbial Inoculants Enhance Maize Productivity and Quality in a Maize–Wheat Rotation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Yan, H.; Xu, S.; Lin, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, D. Moderately Deep Banding of Phosphorus Enhanced Winter Wheat Yield by Improving Phosphorus Availability, Root Spatial Distribution, and Growth. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 220, 105388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedziński, T.; Rutkowska, B.; Łabętowicz, J.; Szulc, W. Effect of Deep Placement Fertilization on the Distribution of Biomass, Nutrients, and Root System Development in Potato Plants. Plants 2023, 12, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Awan, S.A.; Rizwan, M.; Brestic, M.; Xie, W. Silicon: An Essential Element for Plant Nutrition and Phytohormones Signaling Mechanism under Stressful Conditions. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 100, 301–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, M.; Ahmad, Z.; Ashraf, M.; Afzal, M.; Nawaz, F.; Nafees, M.; Jatoi, W.N.; Malghani, N.A.; Shah, A.N.; Manan, A. Silicon Mitigates Drought Stress in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Through Improving Photosynthetic Pigments, Biochemical and Yield Characters. Silicon 2021, 13, 4757–4772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eghlima, G.; Mohammadi, M.; Ranjabr, M.-E.; Nezamdoost, D.; Mammadov, A. Foliar Application of Nano-Silicon Enhances Drought Tolerance Rate of Pot Marigold (Calendula officinalis L.) by Regulation of Abscisic Acid Signaling. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabir, A.; Waraich, E.; Ahmad, M.; Hussain, S.; Asghar, H.; Haider, A.; Ahmad, Z.; Ullah, S. Silicon-Mediated Improvement in Maize (Zea mays L.) Resilience: Unrevealing Morpho-Physiological, Biochemical, and Root Attributes Against Cadmium and Drought Stress. Silicon 2024, 16, 3095–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, S.; Reddy, K.; Li, J. Silicon Enhances Plant Vegetative Growth and Soil Water Retention of Soybean (Glycine max) Plants under Water-Limiting Conditions. Plants 2022, 11, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Liu, H.; Fu, Y.; Li, P.; Li, S.; Gao, Y. Regulatory Effects of Silicon Nanoparticles on the Growth and Photosynthesis of Cotton Seedlings under Salt and Low-Temperature Dual Stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Chu, C.; Wei, H.; Zhang, L.; Ahmad, Z.; Wu, S.; Xie, B. Ameliorative Effects of Silicon Fertilizer on Soil Bacterial Community and Pakchoi (Brassica chinensis L.) Grown on Soil Contaminated with Multiple Heavy Metals. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 267, 115411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirisuntornlak, N.; Ullah, H.; Sonjaroon, W.; Anusontpornperm, S.; Arirob, W.; Datta, A. Interactive Effects of Silicon and Soil PH on Growth, Yield and Nutrient Uptake of Maize. Silicon 2021, 13, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.-L.; Xu, K.-X.; Zhang, C.; Qiu, L.-X.; Liu, Y.-W.; Qiang, Z.-Y.; Huang, J.; Guan, D.-X. Silicon Application Increases Phosphorus Uptake by Rice: Dynamic Rhizosphere Processes. Earth Crit. Zone 2025, 2, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Li, W.; Jiang, Z.; Li, Y.; Shen, X.; Nuo, M.; Zhang, H.; Xue, B.; Zhao, G.; Tian, P.; et al. Silicon Enhanced Phosphorus Uptake in Rice under Dry Cultivation through Root Organic Acid Secretion and Energy Distribution in Low Phosphorus Conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1544893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rubie, J.A.J.; Abdulkareem, M.A. Phosphorus and Silicon Uptake By Corn (Zea mays L.) in Response to Silicon Application in Calcareous Soil. Nabatia 2024, 12, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostic, L.; Nikolic, N.; Bosnic, D.; Samardzic, J.; Nikolic, M. Silicon Increases Phosphorus (P) Uptake by Wheat under Low P Acid Soil Conditions. Plant Soil 2017, 419, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Manna, I.; Sil, P.; Biswas, A.; Bandyopadhyay, M. Exogenous Silicon Alters Organic Acid Production and Enzymatic Activity of TCA Cycle in Two NaCl Stressed Indica Rice Cultivars. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 136, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Pan, X.; Zhang, Y. Silicon Application and Related Changes in Soil Bacterial Community Dynamics Reduced Ginseng Black Spot Incidence in Panax Ginseng in a Short-Term Study. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaller, J.; Puppe, D.; Kaczorek, D.; Ellerbrock, R.; Sommer, M. Silicon Cycling in Soils Revisited. Plants 2021, 10, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da, G.; Júnior, S.; Prado, R.; Campos, C.; Agostinho, F.; Silva, S.L.; Santos, L.; Castellanos, L. Silicon Mitigates Ammonium Toxicity in Yellow Passionfruit Seedlings. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2019, 79, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Lu, P.; Ma, P.; Zhou, H.; Yang, M.; Zhai, X.; Chen, M.; Wang, H.; Li, W.; Bai, W.; et al. Processes at the Soil–Root Interface Determine the Different Responses of Nutrient Limitation and Metal Toxicity in Forbs and Grasses to Nitrogen Enrichment. J. Ecol. 2021, 109, 927–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.Y.; Xu, S.N.; Qin, D.N.; Li, W.; Zhao, X.Q. Role of Silicon in Mediating Phosphorus Imbalance in Plants. Plants 2021, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, Y.; Singh, P.; Bajguz, A.; Alam, P.; Hayat, S. Silicon Mediated Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants Using Physio-Biochemical, Omic Approach and Cross-Talk with Phytohormones. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 166, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-H.; Khan, A.; Lee, I.-J. Silicon: A Duo Synergy for Regulating Crop Growth and Hormonal Signaling under Abiotic Stress Conditions. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2015, 36, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merhij, E.; Abu Altemen, W.; Jasim, A. The Effect of Silicon, Tillage and the Interaction between Them on Some Antioxidants and Phytohormones during Drought Stress of Maize (Zea mays L.) Plants. Plant Arch. 2019, 19, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, D.; Vishwakarma, K.; Singh, V.; Prakash, V.; Sharma, S.; Muneer, S.; Nikolic, M.; Deshmukh, R.; Vaculík, M.; Corpas, F. Silicon Crosstalk with Reactive Oxygen Species, Phytohormones and Other Signaling Molecules. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 408, 124820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Bilal, S.; Khan, A.L.; Imran, M.; Shahzad, R.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Al-Rawahi, A.; Al-Azhri, M.; Mohanta, T.K.; Lee, I.-J. Silicon and Gibberellins: Synergistic Function in Harnessing ABA Signaling and Heat Stress Tolerance in Date Palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.). Plants 2020, 9, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Murad, M.; Khan, A.L.; Muneer, S. Silicon in Horticultural Crops: Cross-Talk, Signaling, and Tolerance Mechanism under Salinity Stress. Plants 2020, 9, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souri, Z.; Khanna, K.; Karimi, N.; Ahmad, P. Silicon and Plants: Current Knowledge and Future Prospects. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2021, 40, 906–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Liang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Jin, X.; Hou, L.; Shi, Y.; Ahammed, G.J. Silicon Compensates Phosphorus Deficit-Induced Growth Inhibition by Improving Photosynthetic Capacity, Antioxidant Potential, and Nutrient Homeostasis in Tomato. Agronomy 2019, 9, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Prasad, S.; Sharma, S.; Dubey, N.; Ramawat, N.; Prasad, R.; Singh, V.; Tripathi, D.; Chauhan, D. Silicon and Nitric Oxide-mediated Mechanisms of Cadmium Toxicity Alleviation in Wheat Seedlings. Physiol. Plant. 2022, 174, e13065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamayun, M.; Sohn, E.-Y.; Afzal Khan, S.; Shinwari, Z.; Khan, A.; Lee, I.-J. Silicon Alleviates the Adverse Effects of Salinity and Drought Stress on Growth and Endogenous Plant Growth Hormones of Soybean (Glycine max L.). Abstr. Pap. 2010, 42, 1713–1722. [Google Scholar]

- Tisserant, E.; Malbreil, M.; Kuo, A.; Kohler, A.; Symeonidi, A.; Balestrini, R.; Charron, P.; Duensing, N.; Frei Dit Frey, N.; Gianinazzi-Pearson, V.; et al. Genome of an Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus Provides Insight into the Oldest Plant Symbiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 111, 20117–20122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Shi, N.; Jiang, R.; Zhang, F.; Feng, G. In Situ Stable Isotope Probing of Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria in the Hyphosphere. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, erv561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Fan, J.; Ding, X.; Zhang, F.; Feng, G. Hyphosphere Interactions between an Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus and a Phosphate Solubilizing Bacterium Promote Phytate Mineralization in Soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 74, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Feng, G.; Declerck, S. Signal beyond Nutrient, Fructose, Exuded by an Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus Triggers Phytate Mineralization by a Phosphate Solubilizing Bacterium. ISME J. 2018, 12, 2339–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiboland, R.; Moradtalab, N.; Aliasgharzad, N.; Es’haghi, Z.; Feizy, J. Silicon Influences Growth and Mycorrhizal Responsiveness in Strawberry Plants. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2018, 24, 1103–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-E.; Adhikari, A.; Kang, S.-M.; You, Y.-H.; Joo, G.-J.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, S.-J.; Lee, I.-J. Isolation and Characterization of the High Silicate and Phosphate Solubilizing Novel Strain Enterobacter Ludwigii GAK2 That Promotes Growth in Rice Plants. Agronomy 2019, 9, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandhol, N.; Rai, P.; Mishra, V.; Pandey, S.; Kumar, S.; Deshmukh, R.; Sharma, S.; Singh, V.; Tripathi, D. Silicon Regulates Phosphate Deficiency through Involvement of Auxin and Nitric Oxide in Barley Roots. Planta 2024, 259, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuyas, L.; Jing, L.; Pluchon, S.; Arkoun, M. Effect of Si on P-Containing Compounds in Pi-Sufficient and Pi-Deprived Wheat. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 22, 1873–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasukawa, H.; Tajima, R. Preliminary Results on the Application of Phosphorus and Silicon to Improve the Post-Transplantation Growth of High-Density Nursery Seedlings. Agronomy 2025, 15, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakir, R.; Horuz, A. Role of silicon in the phosphorus nutrition and growth of the oats (Avena sativa L.) at different phosphorus levels. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2021, 31, 1610–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, W.B.S.; Teixeira, G.C.M.; de Mello Prado, R.; Rocha, A.M.S. Silicon Mitigates Nutritional Stress of Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Calcium Deficiency in Two Forages Plants. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, B.; Xu, D.; Zhou, W.; Wu, Y.; Mou, W. Silicon Reduce Structural Carbon Components and Its Potential to Regulate the Physiological Traits of Plants. Plants 2025, 14, 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.-X.; Guan, D.-X.; Liu, Y.-W.; Luo, Y.; Teng, H.H.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Ma, L.Q. Interactions of Silicon and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Phosphorus Uptake during Rice Vegetative Growth. Geoderma 2025, 454, 117184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbdEL-Azeiz, E.; Faiyad, R. Improving Maize Tolerance to Salinity and Low Available Phosphorus Situation by Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Potassium Silicate. Egypt. J. Soil Sci. 2025, 65, 1499–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Pang, Z.; Feng, X.; Wang, Y.; Peng, H.; Liang, Y. Comparison of the Effects of Silicic Acid, Organosilicon and Nano-Silicon on Rice Cell Wall Phosphorus. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 227, 110089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mückschel, F.; Selzer, T.; Hauschild, M.; Santner, J. Enhancing Crop P Uptake and Reducing Fertilizer P Loss by Si-P Co-Fertilization? Plant Soil 2025, 517, 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fertilizer | Applied Rate/Method | Soil Type (pH) | Crop/Rotation | Observed Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Struvite (recovered from chicken manure) | 30–60 kg P ha−1 | Alluvial soil (pH 6.22, available P 14.9 mg/kg) | Oryza sativa, Triticum aestivum rotation | Sustained grain yield over two seasons, increased soil available P and Mg, improved P uptake efficiency. | [137] |

| Struvite (Crystal Green SGN 300, Ostara) | 11.4 Mg ha−1 | Loamy soil (pH 7.4) | Zea mays | Yield comparable to soluble P fertilisers, reduced P runoff. | [16] |

| Struvite (from wastewater) | 257 kg P ha−1 | Acidic soil (pH 5.7) | Cicer arietinum (cv. Neelam), Triticum aestivum (cv. Scepter) | Increased root growth and P uptake, improved nodulation under low P. | [138] |

| Bone char | 4 t ha−1 yr−1 | Acidic soil (pH 5.08) | Zea mays, Glycine max | Increased grain yield and improved soil P, Ca, Mg. | [133] |

| Bone char | 49 kg ha−1 (average of 3 crops) | Moderately Cd-contaminated, P-deficient soil (pH 5.3–6.4) | Lactuca sativa var. crispa (cv. Lollo Rossa), Triticum aestivum (cv. Fiorina), Solanum tuberosum (cv. Molli) | Increased yield and dry matter, Cd immobilisation. | [139] |

| Surface-modified bone char (BCplus) | 45 kg P ha−1 | Sandy, P-deficient soil (pH 5.2) | Hordeum vulgare, Brassica napus, Triticum aestivum, Lupinus angustifolius, Secale cereale | Enhanced soil-available P and improved P uptake. | [140] |

| SiGS ® + Barrier Si-Ca ® | 500 kg ha−1 soil + 1 dm3 ha−1 foliar | Sandy soil (pH 5.4–6.3) | Zea mays | Increased grain yield, improved yield quality and dry matter. | [141] |

| Si-Ca fertiliser (≥25% CaO, ≥SiO2) | 2.25 t ha−1 | Mildly Cd-contaminated paddy soil (pH 6.0, available P 8.54 mg/kg) | Oryza sativa | Improved soil quality, increased yield and grain quality. | [142] |

| Silicon biopreparations (AdeSil, ZumSil) | Seed dressing 0.5 kg/100 kg seed + foliar 0.5 L ha−1 (2×) | Cambisol | Triticum aestivum (cv. Harenda, Serenada, Rusałka) | Increased yield, improved disease resistance. | [143] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kulus, I.; Ciereszko, I. Enhancing Cereal Crop Tolerance to Low-Phosphorus Conditions Through Fertilisation Strategies: The Role of Silicon in Mitigating Phosphate Deficiency. Agronomy 2026, 16, 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030388

Kulus I, Ciereszko I. Enhancing Cereal Crop Tolerance to Low-Phosphorus Conditions Through Fertilisation Strategies: The Role of Silicon in Mitigating Phosphate Deficiency. Agronomy. 2026; 16(3):388. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030388

Chicago/Turabian StyleKulus, Ilona, and Iwona Ciereszko. 2026. "Enhancing Cereal Crop Tolerance to Low-Phosphorus Conditions Through Fertilisation Strategies: The Role of Silicon in Mitigating Phosphate Deficiency" Agronomy 16, no. 3: 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030388

APA StyleKulus, I., & Ciereszko, I. (2026). Enhancing Cereal Crop Tolerance to Low-Phosphorus Conditions Through Fertilisation Strategies: The Role of Silicon in Mitigating Phosphate Deficiency. Agronomy, 16(3), 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030388