1. Introduction

As the world population is expected to reach 10.3 billion by the mid-2080 [

1], increasing food production is essential to meet the food requirements of this rapidly growing society. Until now, the increase in final production has been achieved thanks to the combination of variety breeding, an increase in cultivation area, and the great use of inputs. However, since many crops are nearing their maximum physiological yield [

2], the negative effects of excessive fertilizer application are undeniable in the environment [

3], and natural resources are increasingly limited.

In view of these limitations, precision agriculture (PA) has been presented in the last few decades as a solution that allows site-specific crop management (SSCM) [

4] to improve productive potential and efficiency of farm inputs [

5].

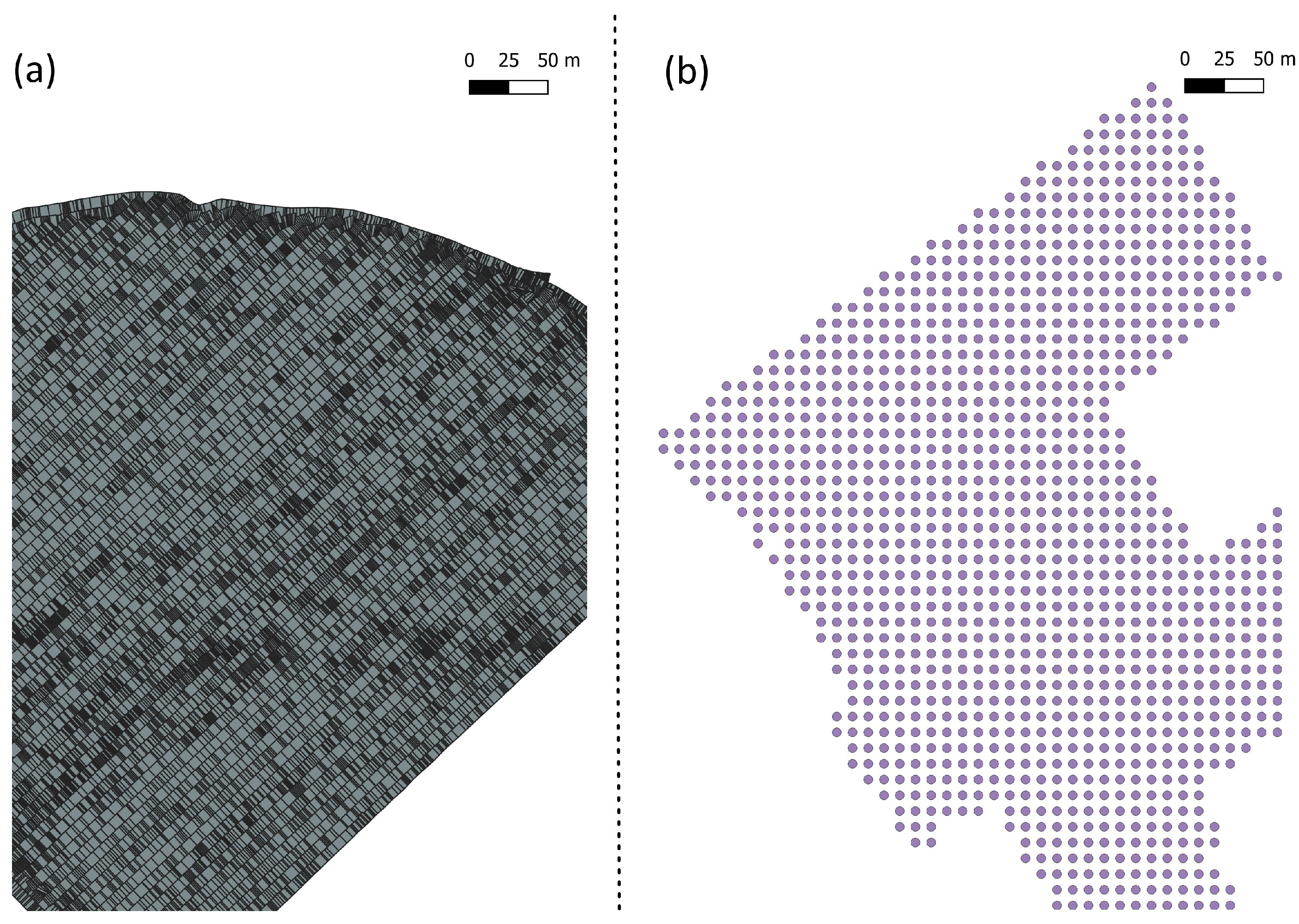

Within PA, some of the most important sources of information are yield maps and their precise location data, provided by yield monitors installed in combine harvesters and their Global Positioning Systems (GPS) [

6]. Using these data for SSCM and the creation of yield prediction models. Nevertheless, even as more growers adopt these technologies, these data are often underused by growers and the industry [

7], mainly because of existing anomalies that could jeopardize future decisions based on these data. These errors can be classified into four groups [

8]: harvest dynamics (lag time, filling and emptying time), measurement errors related to yield and moisture observations, positioning system accuracy, and harvester operator (speed, harvest turns, and headlands).

In this regard, several authors have highlighted the need to detect and filter these errors prior to any subsequent data analysis. Numerous methodologies have been proposed, most of which have been tested in only a limited number of fields and production areas. Overall, two main approaches are commonly employed:

Global filtering, in which outliers are removed from the dataset [

9]. In the literature, global filtering comprises several types of filters, including the use of complementary harvest data (e.g., moisture measurements, harvester speed, or harvesting pass), biological limits of the crop, and parametric filtering criteria.

Local, post-processing filtering, where a neighborhood of observations is defined, and inliers are subsequently removed [

4,

6,

8,

10]. Local filtering can be performed through different approaches, such as the application of the Local Moran’s spatial correlation index (LM) [

6,

11], clustering algorithms [

7,

12], or expert-based manual filtering [

13].

In both cases, interpolation techniques such as the Block Kriging and Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW) methods are commonly used to replace the removed data points.

Nevertheless, data-cleaning protocols that rely on complementary harvest information are limited by the fact that such ancillary data are not always available [

14]. Similarly, parametric filters based on statistical descriptors such as the mean and standard deviation may be unsuitable for large, multi-location datasets with a large number of fields, as the proportion of fields with non-normal distributions tends to increase. Conversely, local filtering techniques are typically characterized by high computational demands, which do not necessarily yield superior performance when the cleaned data are subsequently used to train ML models [

15], and many of these approaches lack full automation.

In this sense, researchers in other domains have recommended data transformations, such as the logarithmic transformation, the min-max method, or z-score normalization [

16], to obtain a dataset with a normal distribution. Even so, these techniques are not helpful for all datasets and may be difficult to interpret in agriculture. Another feasible option is to use other parameters that are more reliable in non-normal distributions for the filtering process, such as the median or the interquartile range (IQR) [

17].

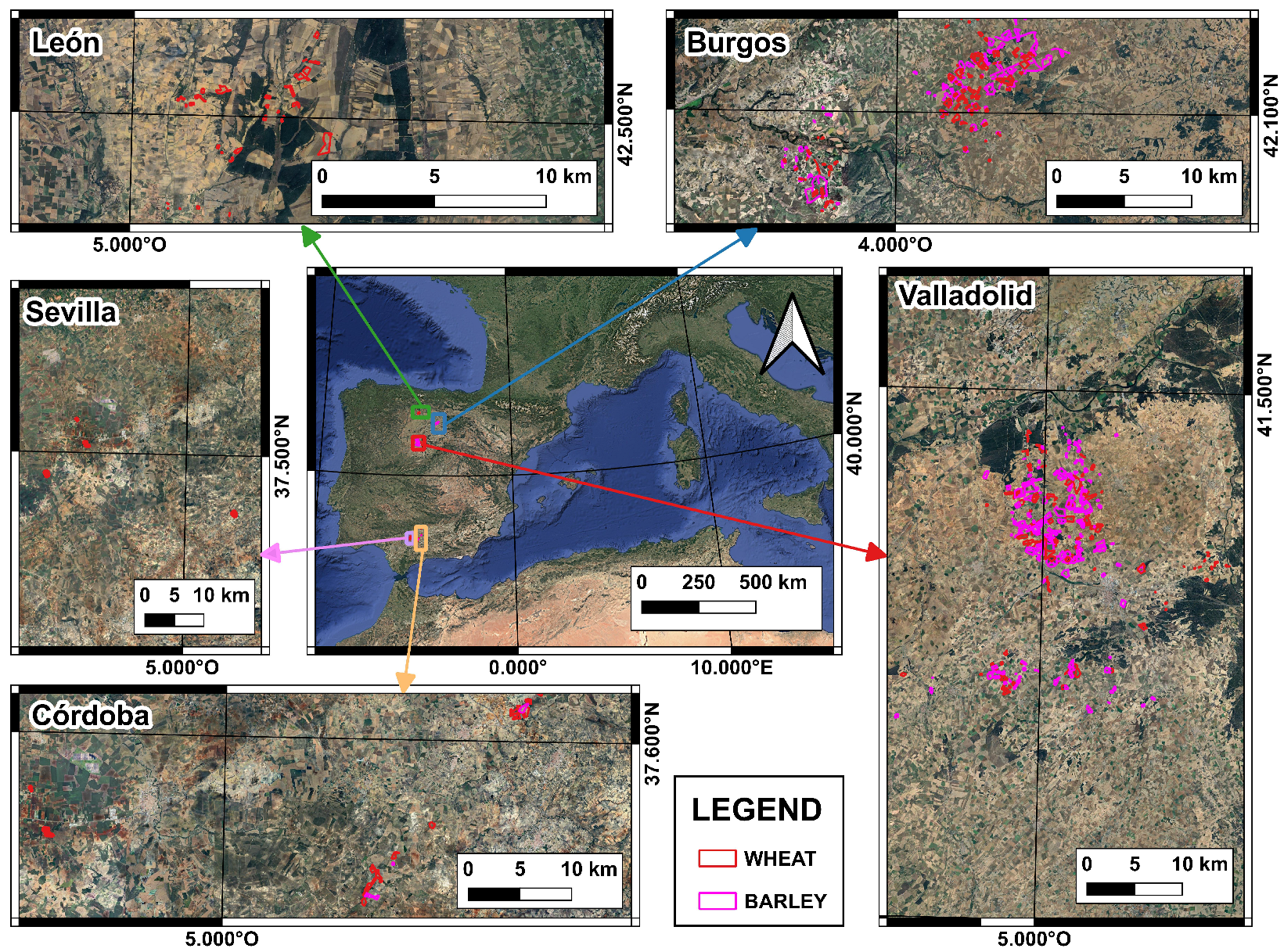

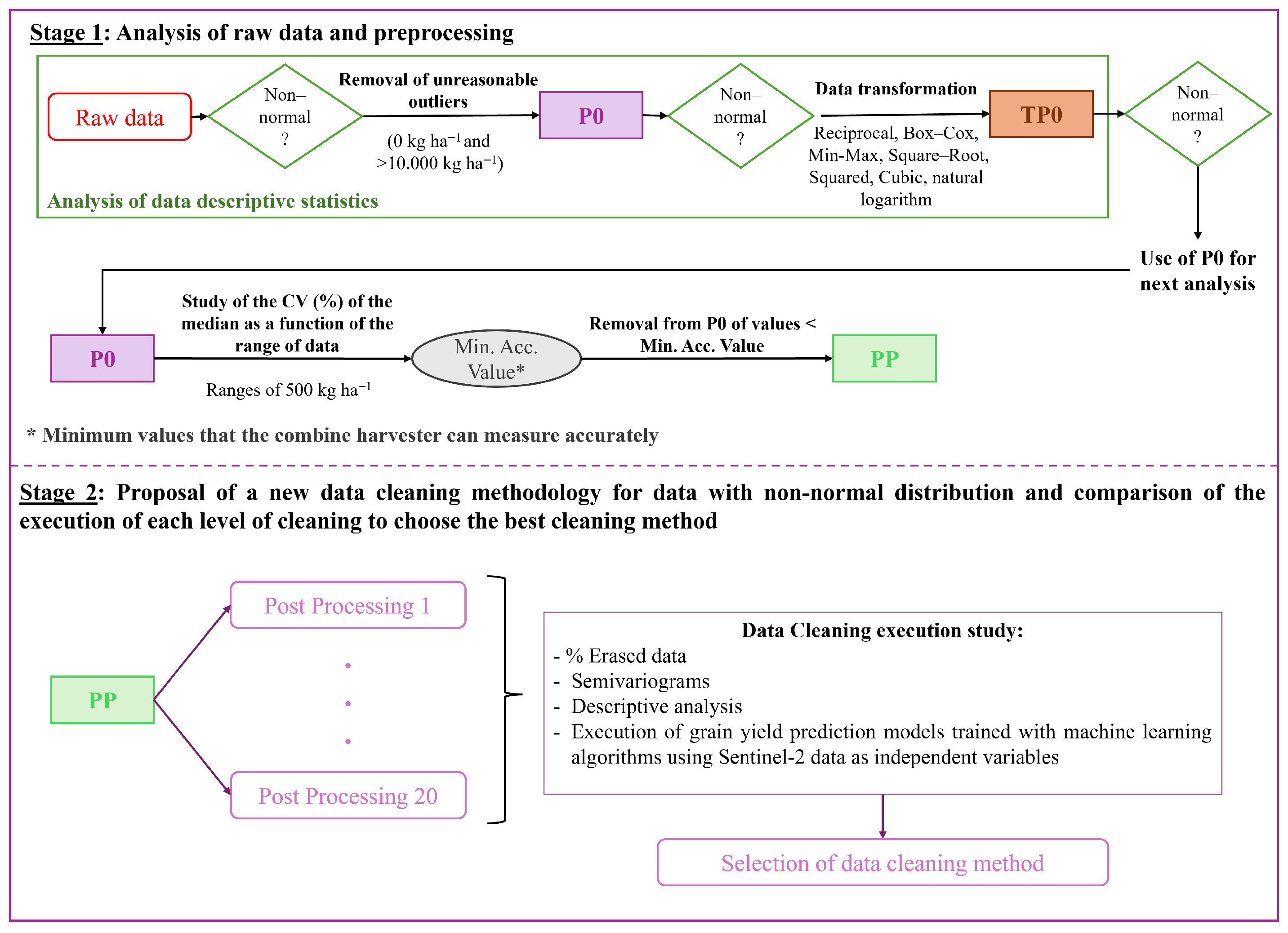

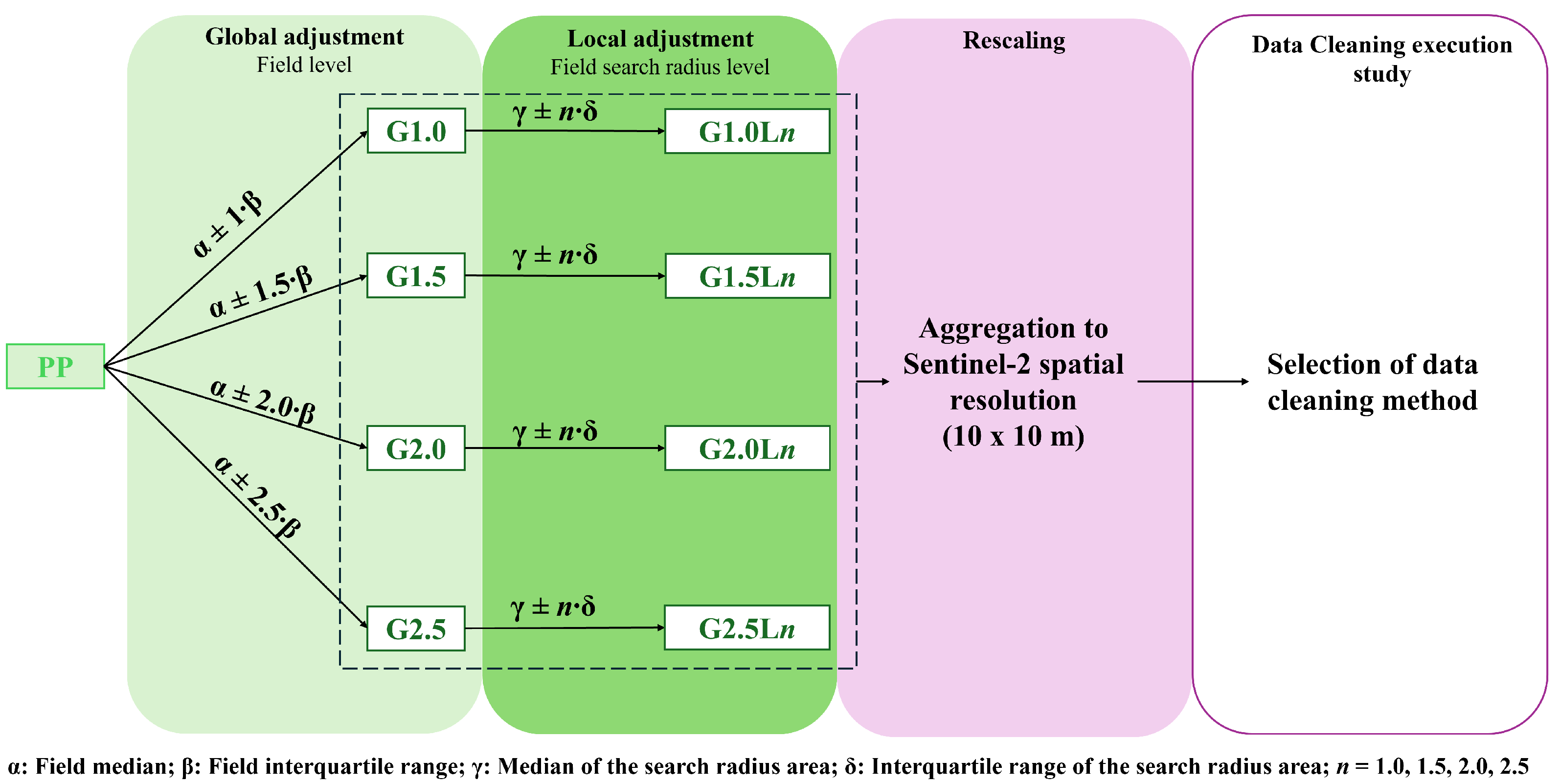

For this purpose, in this paper, the non-normality of raw yield datasets is tested and validated for a large dataset, including two different crops (wheat and barley), five locations, and four different growing seasons. Once this statement is verified, the paper aims to select a new data-cleaning protocol that can be easily automated with low computational expense. This study proposes global and local filtering, using the median and interquartile range as robust statistics to clean skewed data, along with different combinations of coefficient limits. The selection of the optimized data cleaning method is based on an analysis of the data’s internal structure and on enhancing the performance of the machine learning model trained on Sentinel-2 reflectance data and filtered yield data. The proposed method is applied in 7399 ha of wheat and barley.

4. Discussion

The results of the descriptive analysis of the datasets justify the non-normal distribution of the Raw datasets. It also confirms that removing combine harvester overlaps, GPS errors, and yield values outside the possible biological range improves the distribution, increasing the number of fields with a normal distribution in the datasets (from 8.2% to 36.9% of fields, depending on location and crop type). In view of these results, other authors, such as Aworke et al. [

27], have applied data transformations (e.g., logarithmic transformation) to obtain a dataset with a normal distribution. However, those transformations are usually used with small datasets containing few fields. When these transformations are applied to large datasets, as shown in

Table 4, it is evident that this method cannot be applied to all datasets. Therefore, the use of the preprocessed datasets (P0) for the proposed data cleaning processes is highly recommended. The non-normal distribution of the datasets is accounted for, as the proposed approach uses statistics that are not overly influenced by extreme values (Sainani, 2012) [

17].

Other authors like Blasch et al. [

9], Sun et al. [

4], Ping et al. [

12], Robinson and Metternicht [

25], and Gozdowski et al. [

11] have emphasized that the combine harvester has a minimum value of yield that it can measure accurately. For winter cereals such as wheat and barley, the minimum value has been set in the range of 100 and 1000 kg ha

−1, but the criteria to set one value or another have not yet been explained. The study of the CV

median for each range of yield (

Table 5) helped to set this minimum in 500 kg ha

−1. This decision can be explained from a mathematical point of view: for an increasing range of values, the mean tends to increase while the standard deviation remains similar, resulting in a higher CV

median and yield ranges with lower yields. However, the CV

median of the range of yield from 0 to 500 kg ha

−1 is too high when compared to the next studied range (500 to 1000 kg ha

−1), indicating an unusually high standard deviation.

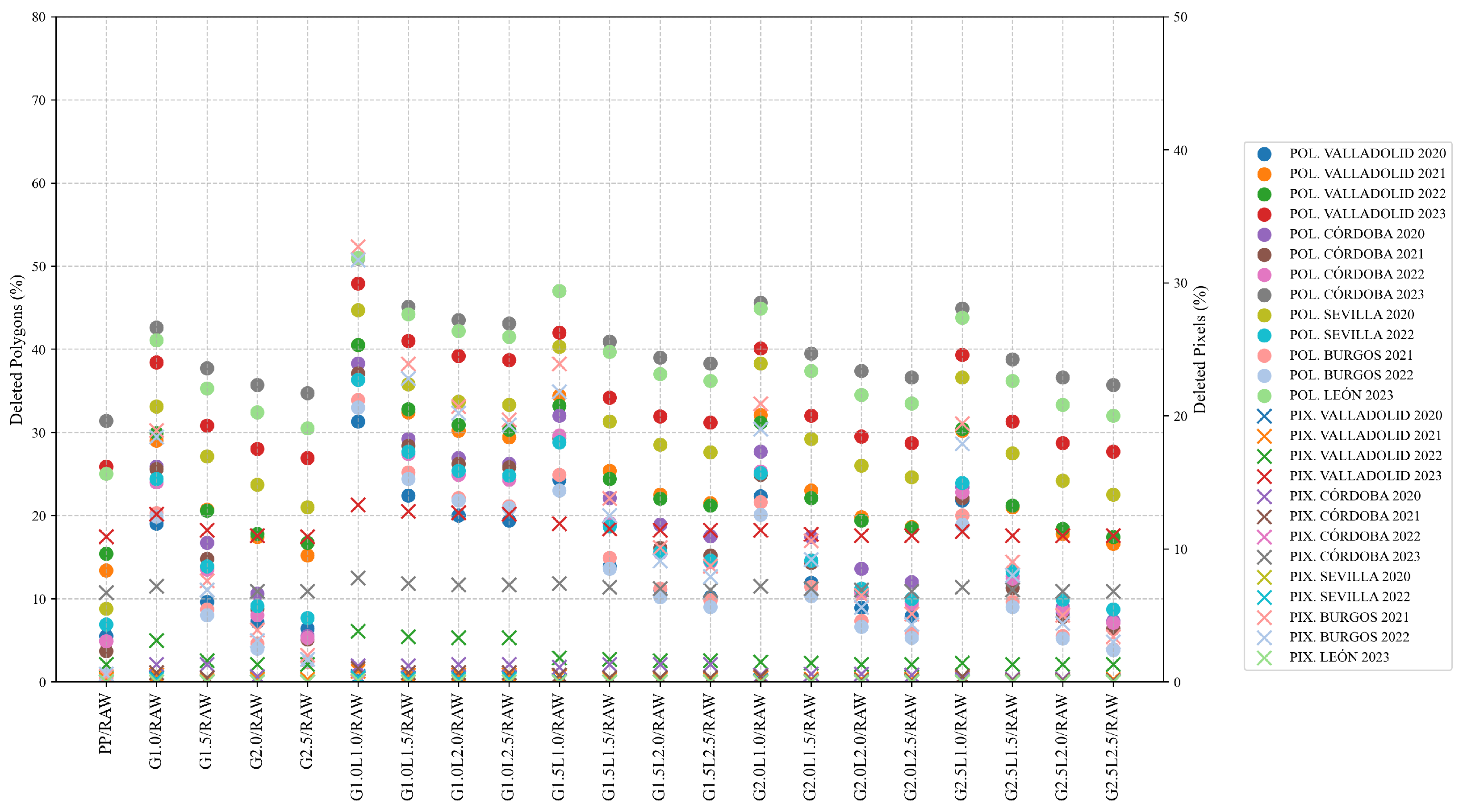

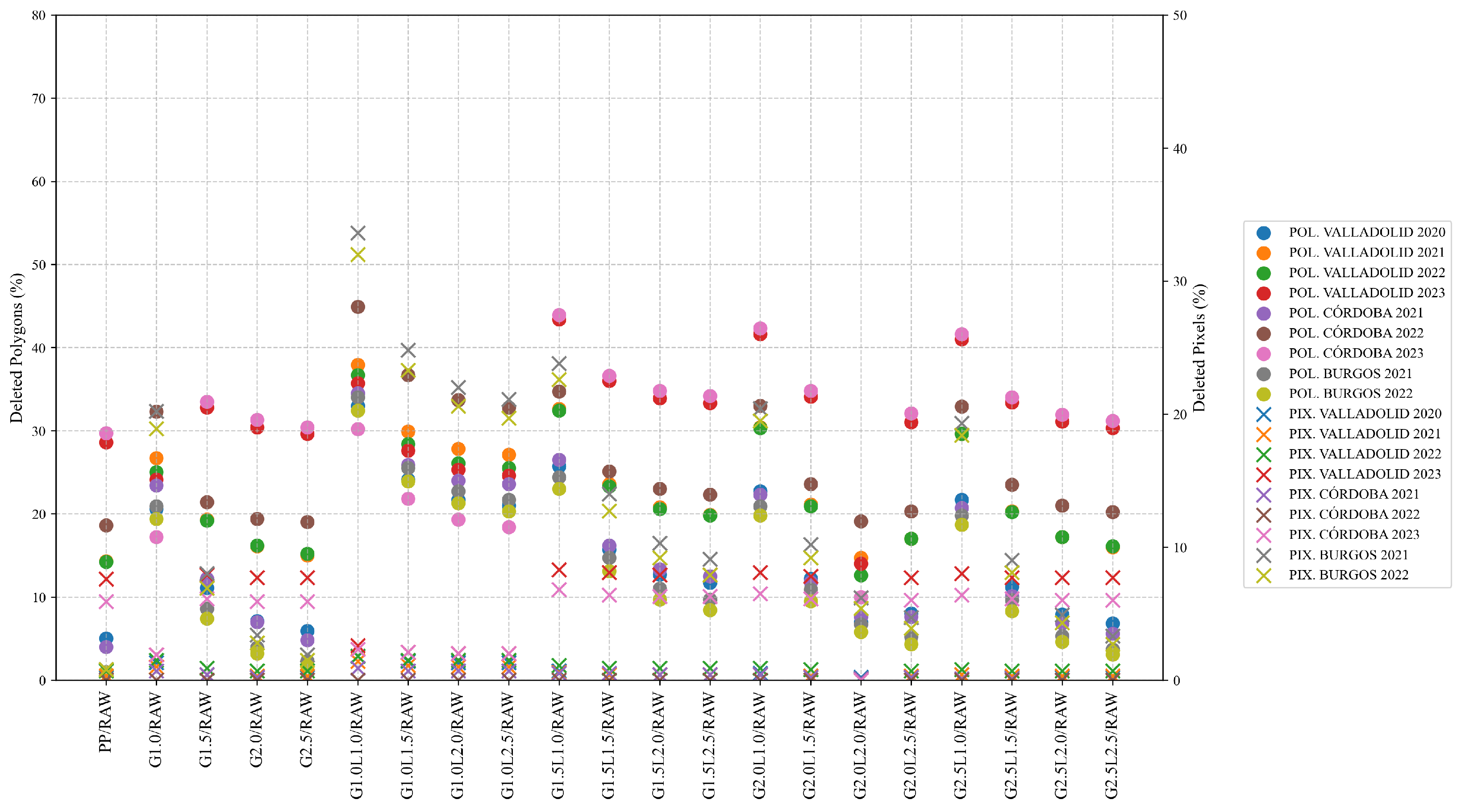

In terms of total erased data at polygon level, the results obtained are aligned with those obtained by other authors, deleting a percentage of data between 10% and 50% [

4,

6,

7,

11,

12,

24,

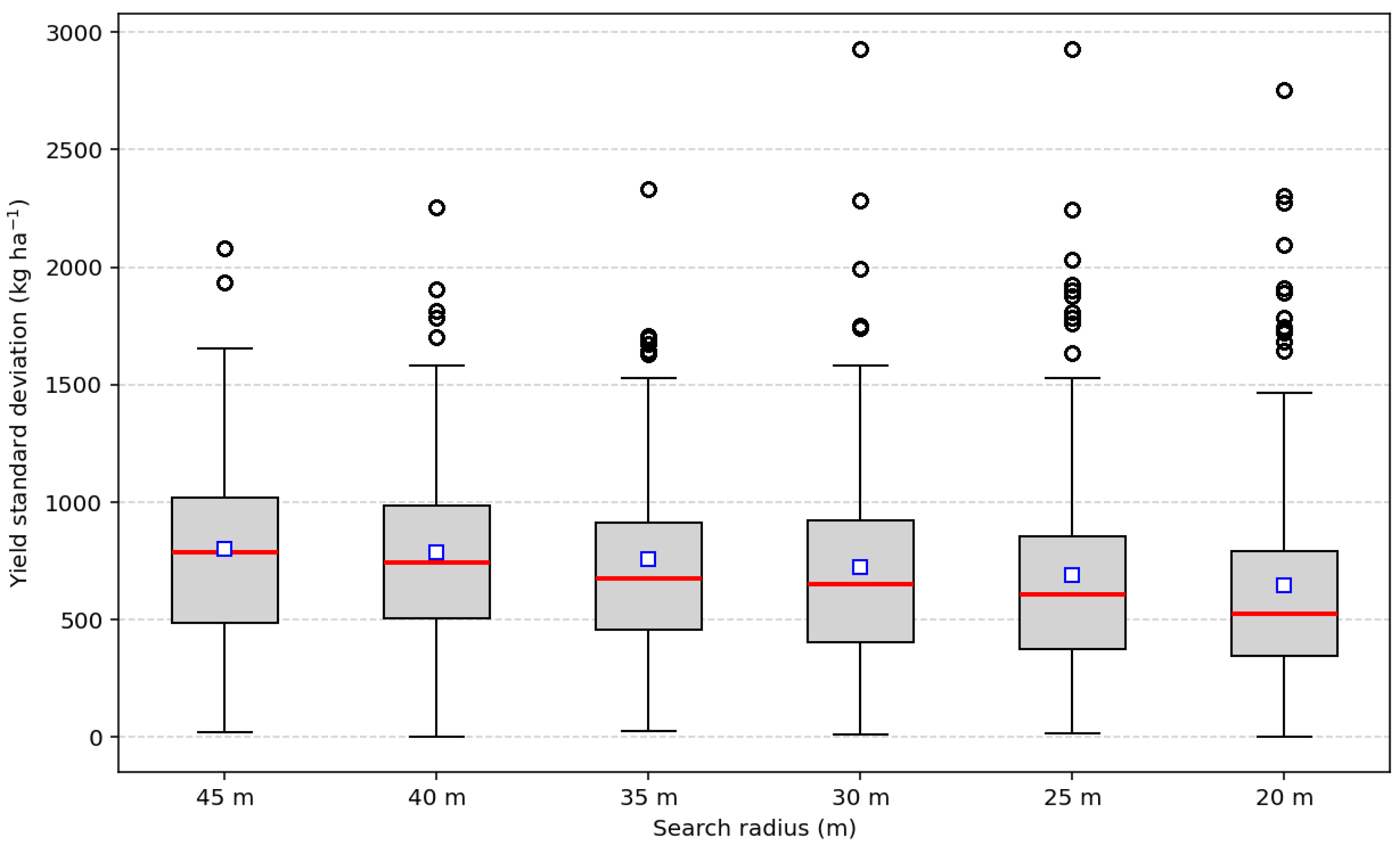

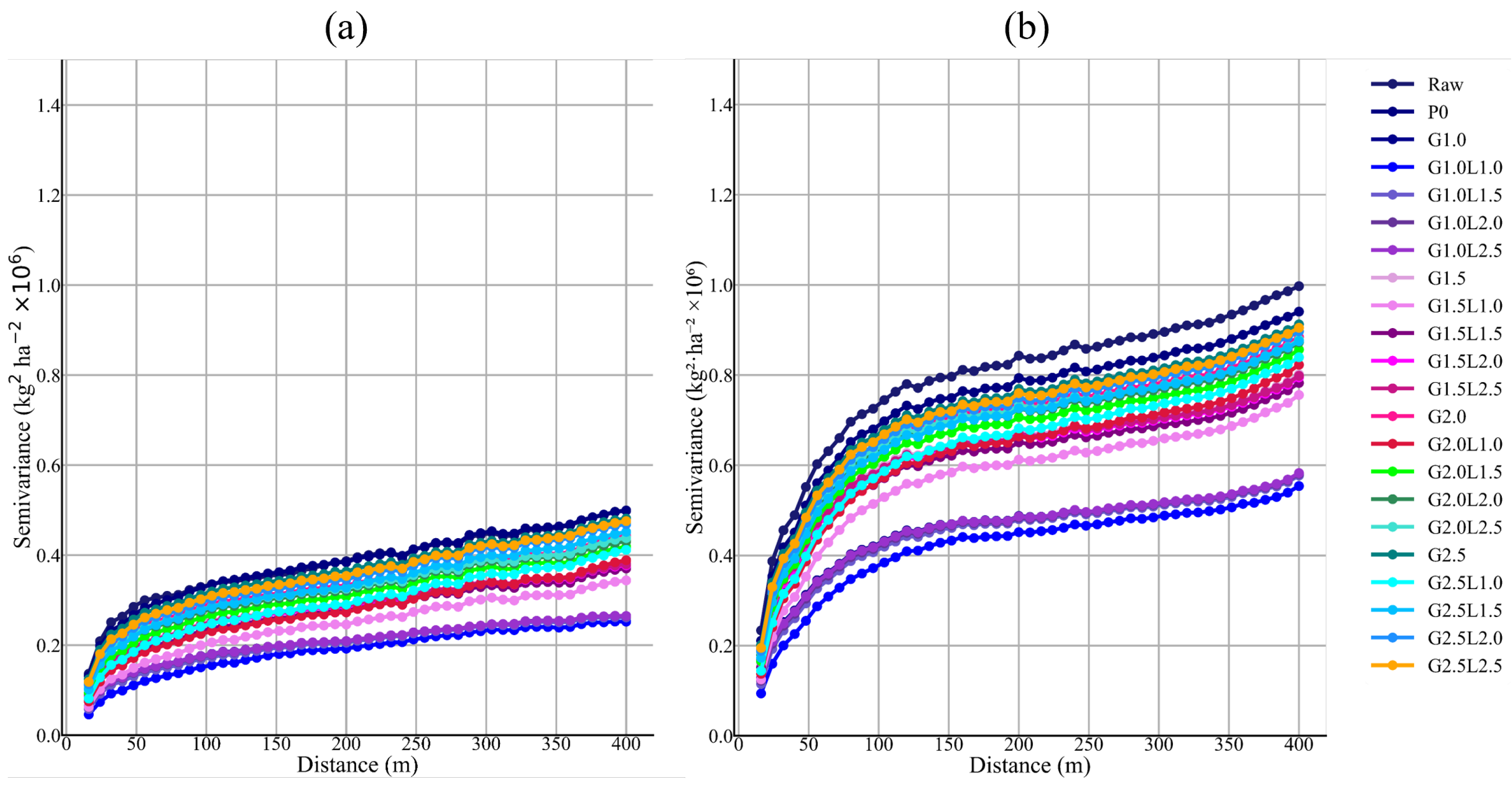

26]. However, if the cleaned yield data is resampled and used with Sentinel-2 at higher spatial resolution, the percentage of deleted data decreases, reaching a maximum of 33.6% of the 10 × 10 m pixels (pixel level). Given concerns about potential bias, the proposed filtering protocol is applied to each field using the median and interquartile range at the global and 40 m neighborhood levels, with the aim of reducing inconsistent values. To validate this measure, not only were statistical indicators used, but semivariograms and validation tests were also reported.

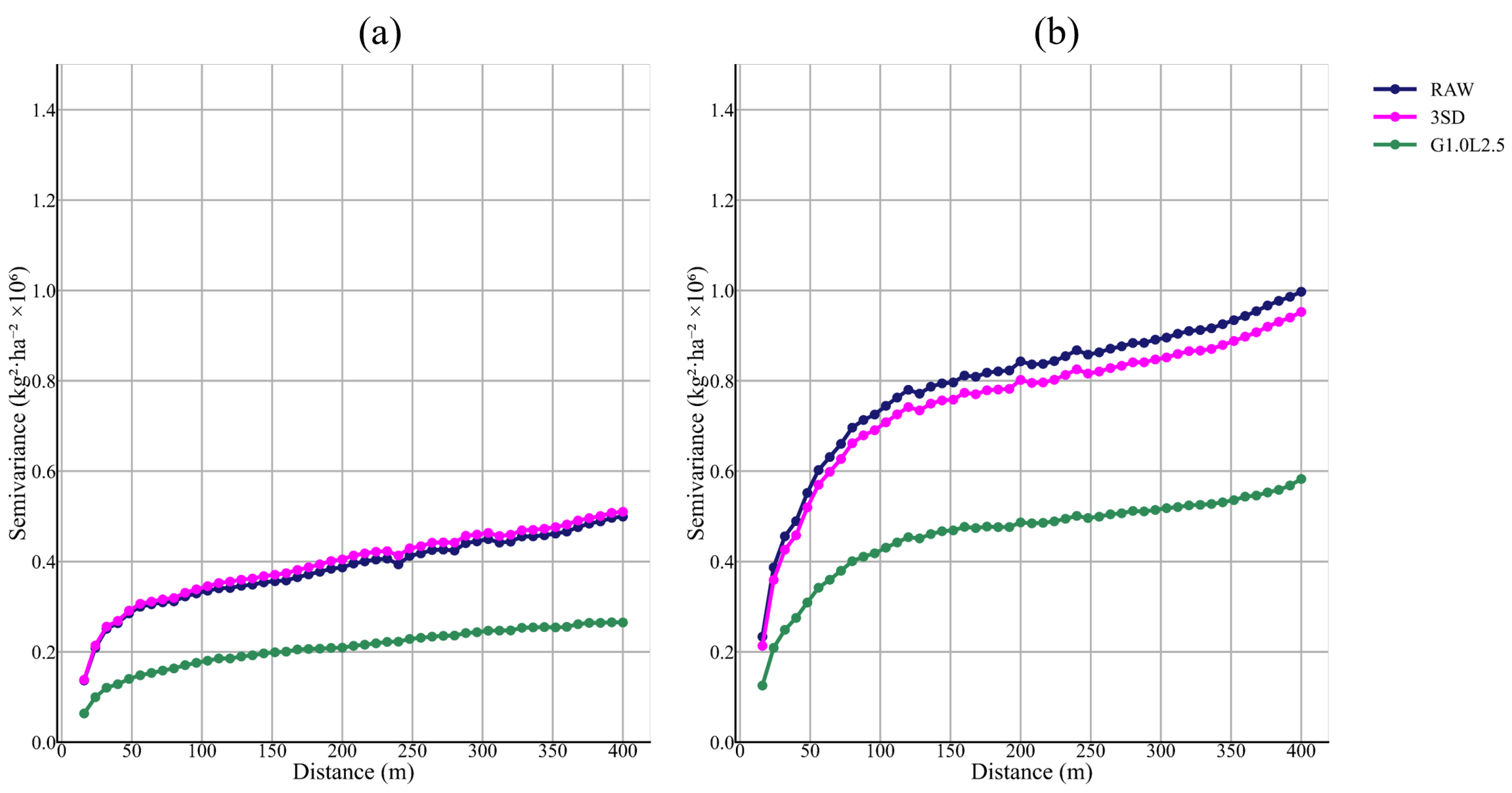

The removal of global outliers and local inliers significantly modified the summary of statistics of the datasets by lowering the CV (34.4–424.1% in the Raw dataset to 4.9–80.1% after cleaning) and standard deviation (22–64%) and increasing the value of mean (9.5–15.5%) and median (8.2–15.7%). Vega et al. [

6] reported a similar decrease in CV, with the datasets’ CV ranging from 88% to 213% before cleaning and from 34% to 46% after cleaning. Other authors have also reported increases of 6–15% in the mean and decreases of 22–64% in the standard deviation, similar to Lyle et al. [

28], who reported increases of 11% and decreases of 47% in the mean and standard deviation, respectively. The increase in the median was also revealed in different crops, reducing the differences between mean and median yield [

12,

24], observing in winter wheat differences < 160 kg ha

−1 [

7]. Considering that a good cleaning method should increase the normality of the distribution of the yield data [

14,

24,

25], these reduced differences between mean and median yield were reflected in the rise of studied yields that present a normal distribution of data, with a maximum value of 82.9% and 78.7% (G1.0L2.5 cleaning level) of the total wheat and barley fields, respectively. Although the proposed protocols cause an increase in elements that meet normality criteria (skewness, −0.5 and 0.5; kurtosis, −2 and 2), another significant group remained outside these thresholds in the most effective method (G1.0L2.5). Residual non-normality does not indicate a sensor or processing system effect, since the yield image values may reflect the influence of the field’s physical environment and crop management on crop productivity. Consequently, anomalous and obvious data could be eliminated using statistical indicators that do not assume strict normality. Moreover, the uncertainty has been reduced after applying the cleaning protocol to the yield datasets, as shown by a substantial reduction in the nugget value [

25] in each proposed cleaned level, being the levels of cleaning of the G1.0 family with local filtering, and G1.5L1.0 the ones that better improved the spatial structure of the yield datasets. In addition, lag distance at which the sill is achieved in the semivariograms is consistent across all proposed cleaning levels, presenting a downward shift in the total semivariance, as observed by Sun et al. [

4]. Therefore, the downward shift in the semivariance is consistent with the elimination of error. At the same time, the semivariogram’s stable range indicates that the spatial dimension of the yield distribution is maintained.

Yield data is a precious source of information for precision agriculture, and therefore, proper cleaning is fundamental to its reliable use. In this context, its use to develop yield prediction models is a common practice. The use of ML to develop prediction models has shown good results, and these techniques are less affected by errors than regression models [

29]. The execution of the two applied ML algorithms helped achieve a balance between cleaning level and prediction quality, as other authors have reported [

15]. All the preselected cleaning levels performed similarly during training for both algorithms, yielding better results than the models trained with Raw and PP yield data. In addition, when the models’ performance is evaluated on the test data, it is evident that R

2 values decrease, while RMSE and MAPE increase substantially in the Raw and PP models, indicating clear overfitting and highlighting the poor quality of the data. The performance of the models trained with the pre-selected cleaning levels remains similar when applied to the test data. The good execution of the models in training and testing, along with the similar results obtained between preselected cleaning levels, indicates that the less restrictive preselected cleaning levels (G1.0L2.5 and G1.5L1.0) are the most suitable protocols for cleaning yield data, as they also erase a lower percentage of yield data (maximum percentage of erased polygons of 42% in wheat and 33% in barley for G1.0L2.5, and maximum of 48% in wheat and 35% in barley for G1.5L1.0). In addition, the range of values continues being similar, while R

2 increases, also reflecting the improvement of the spatial structure of the data, while the RMSE and MAPE values decrease when compared with the crude data, but not substantially, highlighting that the behavioral patter of the data has not changed maintaining the real variability of yield data, and, subsequently, the cleaning process has not introduced bias in the data.

Between G1.0L2.5 and G1.5L1.0 levels of cleaning, the G1.0L2.5 is chosen as the better protocol for cleaning yield data, as the semivariograms have shown that the spatial structure of the cleaned data is better, and the percentage of fields presented a normal distribution is maximum when it is applied (82.9% in wheat and 78.7% in barley for G1.0L2.5, and maximum of 71.9% in wheat and 66.1% in barley for G1.5L1.0.

After choosing the better cleaning protocol, the results were compared with the ones obtained when a more conservative method, commonly found in the literature, is applied, the 3SD method. When both methods were compared, the G1.0L2.5 method significantly improved the spatial structure of the data and significantly increased the percentage of fields with a normal distribution of yield data.

The presented framework for yield data cleaning is proposed as an easily applied approach for cleaning yield data error measurements. As the protocol includes both global and local filtering, both outliers and inliers will be erased. The framework employs a parametric approach at both the global and local levels. However, since the unfiltered datasets do not follow a normal distribution, the median and interquartile range are used as filtering statistics, as the data distribution has less influence on them. The proposed cleaning method was tested on a large dataset across different locations, growing seasons, and two crops, yielding good results. It has lower computational requirements than more complex methods, and the cleaned data was used to train ML models with good results as a form of validation. Future studies should focus on applying the selected data-cleaning method to other locations and crops to assess the quality of the cleaned data and determine whether the same cleaning level can be applied to conditions not included in the present work.

5. Conclusions

The presented study proposes a data-cleaning methodology for yield data in wheat and barley crops, applied to a large dataset. Only georeferenced yield data was used in the proposed methodology, allowing the application to all yield maps generated by the YieldTrack software. Firstly, biological outliers and measurements below 500 kg ha−1 are deleted. Secondly, low-computational-expense parametric global and local filtering is applied, using statistics robust to non-normally distributed data (median and interquartile range). Four different limit coefficients were used for global and local filtering, yielding in 20 cleaning levels, which were compared to select the optimal one. The percentage of deleted data, the spatial structure, a descriptive analysis of the data, and the performance of machine learning models trained and tested on clean data and Sentinel-2 reflectance data were used to select the best approach.

The selected level was the G1.0L2.5. This cleaning method was among the most effective in improving the spatial structure of the data and the predictive performance of machine learning models. The maximum percentage of polygons deleted was 42% and 33% for wheat and barley, respectively, and the percentage of fields that showed a normal distribution after filtering was highest at 82.9% and 78.7% for wheat and barley, respectively. The use of the selected method increased the mean and median of the datasets, and decreased the standard deviation and CV values.

Future work will focus on applying the selected cleaning method to other locations and crops, as well as to the Yield Track software, and on evaluating the quality of the cleaned data not included in the present study. In addition, the results of the present work will enable the development of early yield-prediction models that producers can use to implement site-specific crop management and apply correction measures when necessary.

This approach will enable the training of predictive models for advanced phenological stages, which can be applied to estimate cereal production. These estimations contribute to Sustainable Development Goal 2 (Zero Hunger) by improving food security and agricultural planning, and to Sustainable Development Goal 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) by reducing market uncertainty and facilitating risk management.