Development and Characterization of Novel St-R Translocation Triticale from a Trigeneric Hybrid

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Experimental Design and Evaluation of Agronomic Traits

2.3. Protein Content of Measurement

2.4. Molecular Marker Analysis

2.5. Molecular Cytogenetic Analyses

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

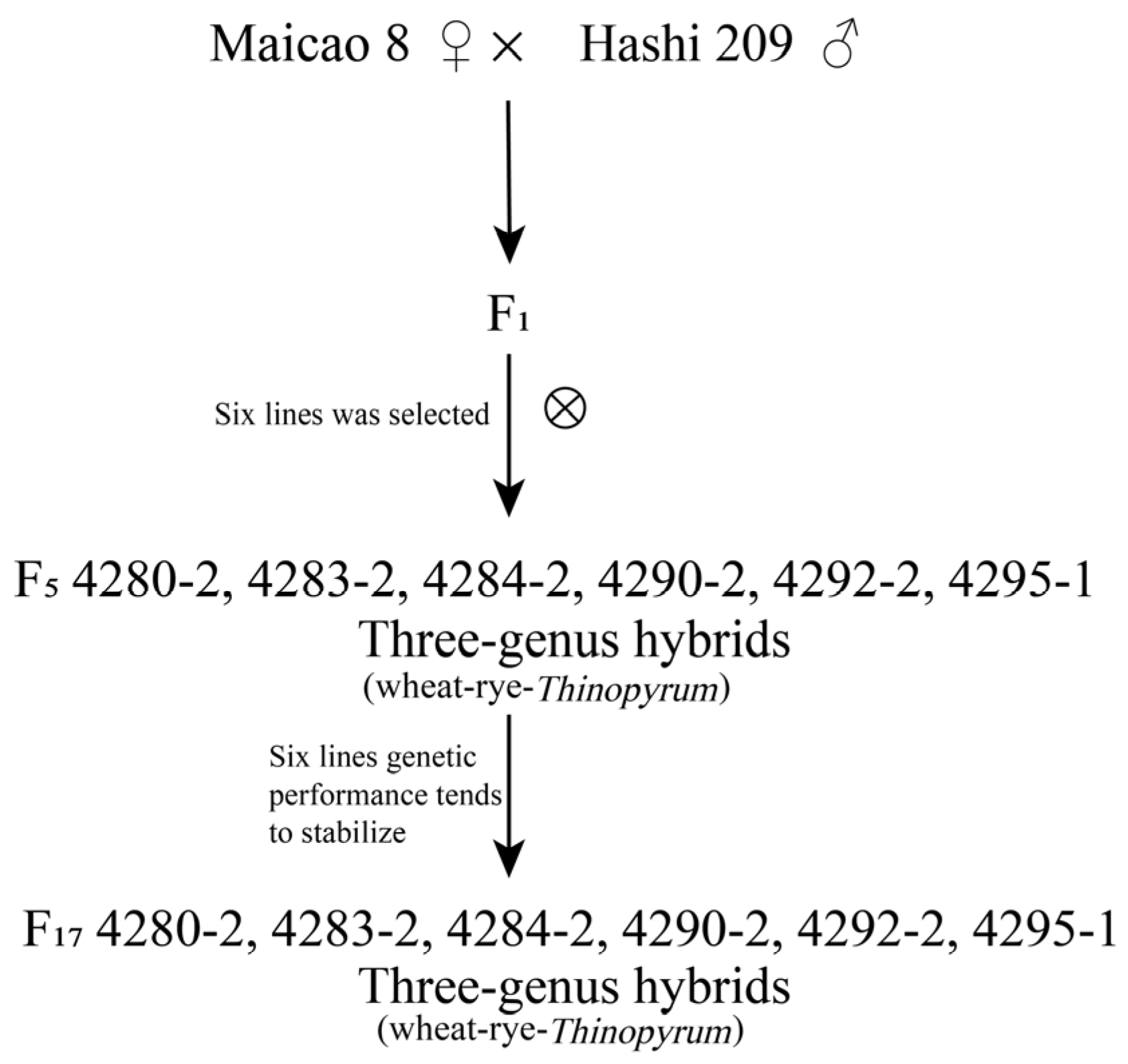

3.1. Development of Triticale Lines and Evaluation of Morphological and Agronomic Traits

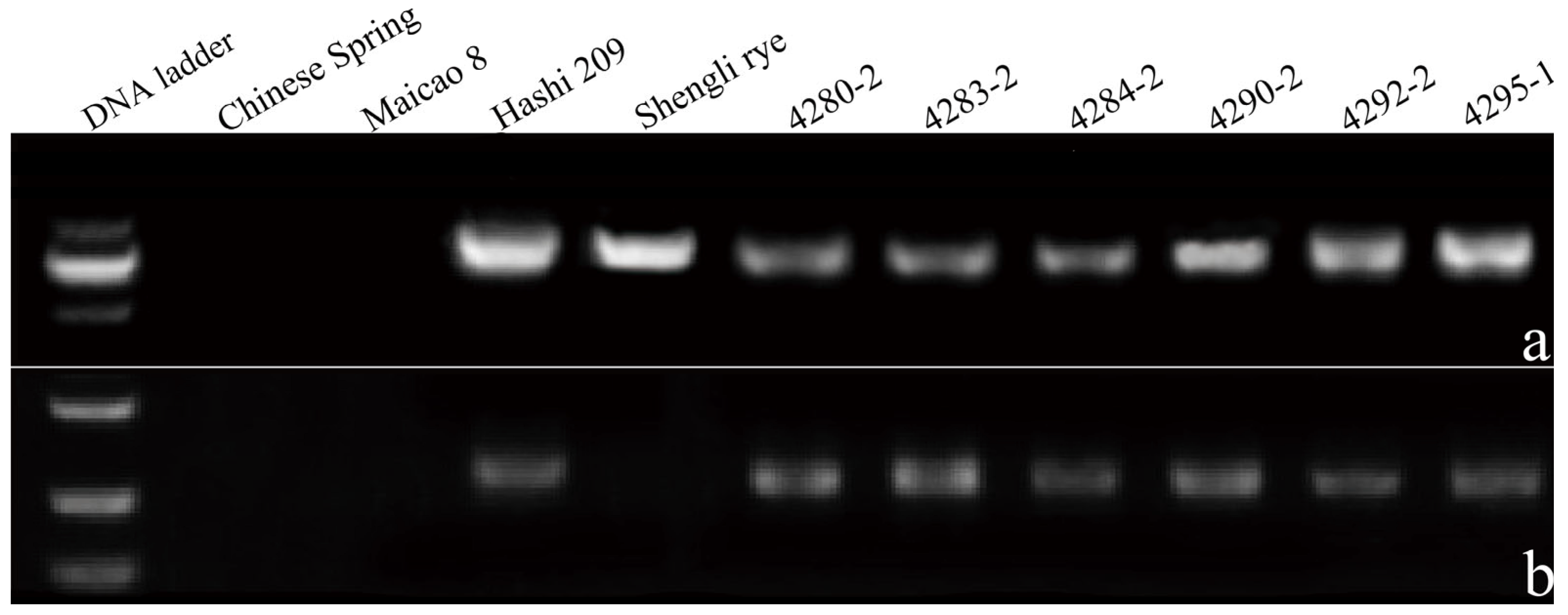

3.2. Molecular Marker Analysis with Genome-Specific Primers pSc119.1, and 2P1-2P2

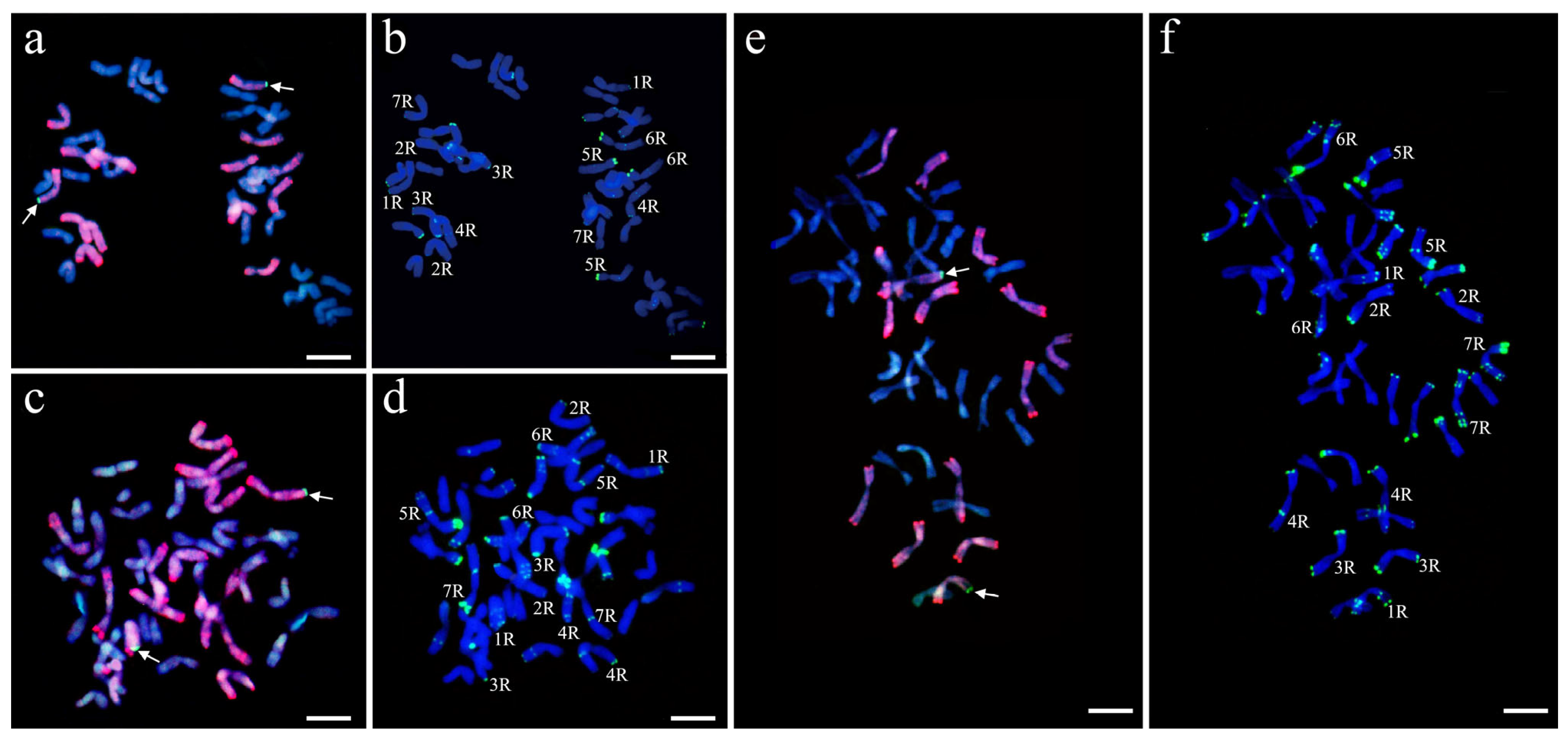

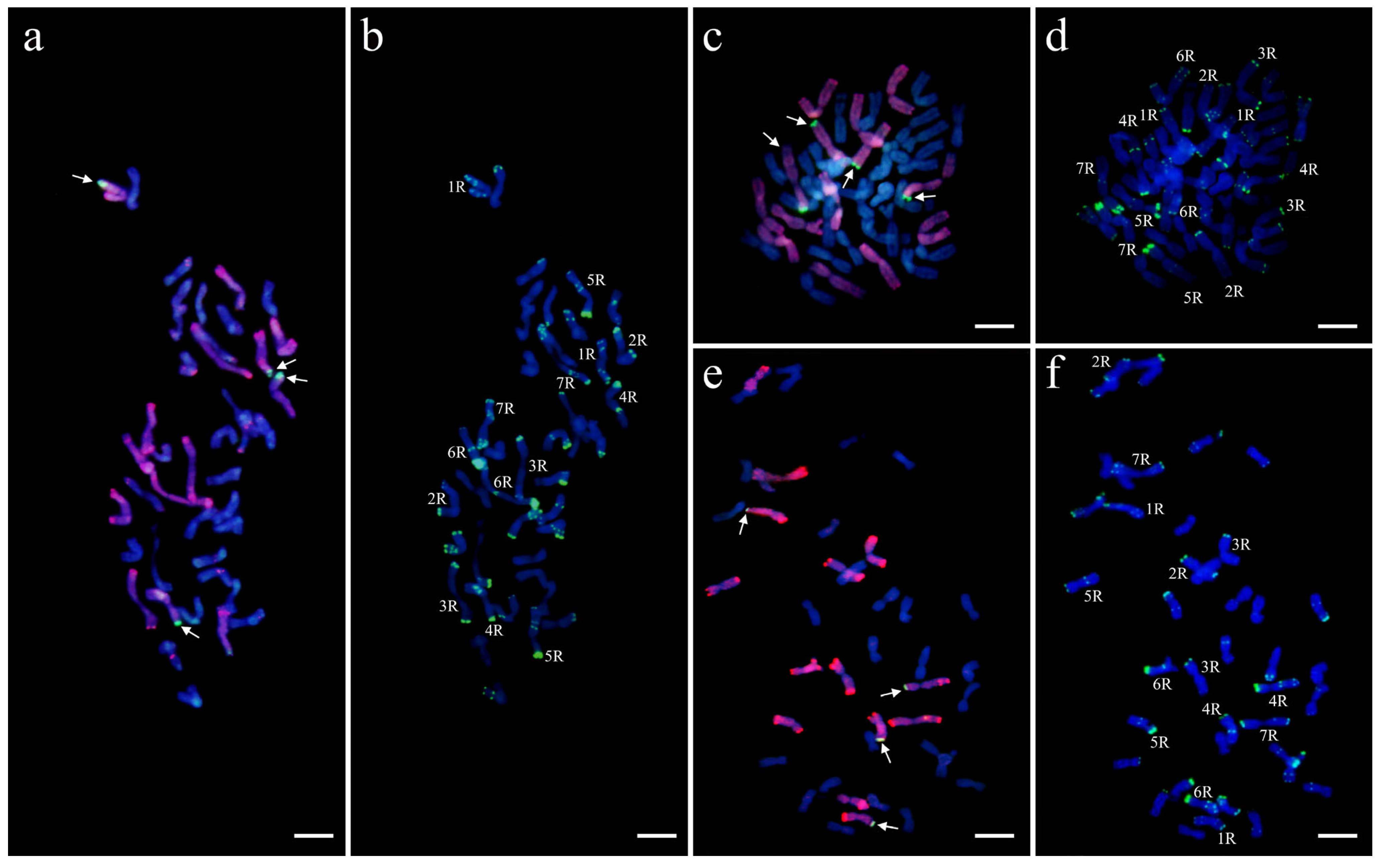

3.3. Cytogenetics Analysis of Triticale with smGISH and FISH

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kalinka, A.; Achrem, M. Reorganization of wheat and rye genomes in octoploid triticale (×Triticosecale). Planta 2018, 247, 807–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, C.H.; Zhang, Z.B.; Yan, G.R.; Wang, F.; Zhao, L.J.; Liu, N.; Abudurezike, A.; Li, Y.S.; Wang, W.; Shi, S.B. Salt-responsive transcriptome analysis of triticale reveals candidate genes involved in key metabolic pathways in response to salt stress. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saed-Moucheshi, A.; Babaei, S.; Ansarshourijeh, F. Innovative multi-trial breeding and genotype screening in triticale (×Triticosecale Wittmack) for enhanced stability under drought stress. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García del Moral, L.F.; Boujenna, A.; Yañez, J.A.; Ramos, J.M. Forage production, grain yield, and protein content in dual-purpose triticale grown for both grain and forage. Agron. J. 1995, 87, 902–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedaner, T.; Flath, K.; Starck, N.; Weißmann, S.; Maurer, H.P. Quantitative-genetic evaluation of resistances to five fungal diseases in a large triticale diversity panel (×Triticosecale). Crops 2022, 2, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, H.; Kumssa, T.T.; Butler, T.J.; Ma, X.F. Triticale improvement for forage and cover crop uses in the southern Great Plains of the United States. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi Alagoz, S.; Hadi, H.; Toorchi, M.; Pawłowski, T.A.; Asgari Lajayer, B.; Price, G.W.; Farooq, M.; Astatkie, T. Morpho-physiological responses and growth indices of triticale to drought and salt stresses. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.R.; Shi, Q.H.; Wang, M.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Su, H.D.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.B.; et al. Functional analysis of the glutathione S-transferases from Thinopyrum and its derivatives on wheat Fusarium head blight resistance. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 1091–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golebiowska-Paluch, G.; Stawoska, I.; Jelonek-Kozioł, M.; Wesełucha-Birczyńska, A.; Kornaś, A. Soil salinity differentiates winter triticale genotypes in physiological and biochemical characteristics of seedlings and consequently their yield. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Xu, L.Y.; Wang, H.H.; Fan, X.T.; Yan, C.H.; Zhang, Y.M.; Jiang, C.T.; Zhou, T.; Guo, Q.; Sun, Y.; et al. Evaluation of dual-purpose triticale: Grain and forage productivity and quality under semi-arid conditions. Agronomy 2025, 15, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S., II. Wheat and rye hybrids. Trans. Bot. Soc. Edinb. 1873, 12, 286–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, C.M.; Rodríguez-Suárez, C.; Atienza, S.G. Tritordeum: Creating a new crop species-the successful use of plant genetic resources. Plants 2021, 10, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurni, S.; Brunner, S.; Buchmann, G.; Herren, G.; Jordan, T.; Krukowski, P.; Wicker, T.; Yahiaoui, N.; Mago, R.; Keller, B. Rye Pm8 and wheat Pm3 are orthologous genes and show evolutionary conservation of resistance function against powdery mildew. Plant J. 2013, 76, 957–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Pozo, A.D.; Méndez-Espinoza, A.M.; Castillo, D. Triticale. In Neglected and Underutilized Crops; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 325–362. [Google Scholar]

- Wolski, T. Present and future in small grain breeding and seed production in Poland. Fragm. Agron. 1995, 12, 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Wolski, T.; Szołkowski, A.; Gryka, J.; Pojmaj, M.S. Current status of winter triticale breeding in Danko. Biuletyn. IHAR 1998, 205/206, 289–297. [Google Scholar]

- Wolski, T.; Oleksiak, T. Triticale production and breeding in Poland: Cultivar development and global impact. In Proceedings of the 5th International Triticale Symposium; Arseniuk, E., Ed.; Plant Breeding and Acclimatization Institute: Radzikow, Poland, 2002; Volume 1, pp. 131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Shchipak, G.V.; Tsupko, Y.V.; Boguslavskyi, R.L.; Matviyets, V.G.; Shchipak, V.G.; Woś, H.; Brzeziński, W. Breeding hexaploid triticale (× Triticosecale Wittmack) of various varietal types with high bread making quality. In Proceedings of the International Scientific-Practical Conference “Triticale-Crop of the 21st Century”; TOV “NIlan-LTD”: Kharkiv, Ukraine, 2017; pp. 57–59. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Li, Y.H.; Cao, L.R.; Liu, P.Y.; Geng, M.M.; Zhang, Q.; Qiu, L.N.; Sun, Q.X.; Xie, C.J. Simultaneous transfer of leaf rust and powdery mildew resistance genes from hexaploid triticale cultivar Sorento into bread wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulaszewski, W.; Belter, J.; Wiśniewska, H.; Szymczak, J.; Skowrońska, R.; Phillips, D.; Kwiatek, M.T. Recovery of 2R·2Sk triticale-Aegilops kotschyi Robertsonian chromosome translocations. Agronomy 2019, 9, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatek, M.T.; Belter, J.; Ulaszewski, W.; Skowrońska, R.; Noweiska, A.; Wiśniewska, H. Molecular identification of triticale introgression lines carrying leaf rust resistance genes transferred from Aegilops kotschyi Boiss. and Ae. tauschii Coss. J. Appl. Genet. 2021, 62, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.T.; Li, G.R.; Jiang, C.Z.; Zhou, Y.W.; Yang, E.N.; Li, J.B.; Zhang, P.; Dundas, I.; Yang, Z.J. Development of a set of wheat-rye derivative lines from hexaploid triticale with complex chromosomal rearrangements to improve disease resistance, agronomic and quality traits of wheat. Plants 2023, 12, 3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.K. Genetics and breeding. Sci. Agric. Sin. 1962, 7, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.X.; Yu, L.; Xing, H.T. Cytogenetics and traits of hybrids F1 between octoploid triticale and common wheat. Acta Bot. Boreali-Occident. Sin. 1994, 14, 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.; Sun, Y.S.; Wu, Z.X. A new triticale cultivar with high yield and good quality-Zhongsi 237. J. Triticeae Crops 2001, 3, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Sun, Y.S.; Chen, X.Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, S.F. Breeding and application of high-quality forage triticale Zhongsi 828. Crops 2003, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Kong, G.C.; Ainiwaer Li, W.H.; Qi, J.C.; Wei, L.J.; Shi, P.C.; Cao, L.P. A new winter forage triticale variety: Shida No. 1. J. Triticeae Crops 2010, 30, 400. [Google Scholar]

- Han, G.H.; Yan, H.W.; Wang, J.; Cao, L.J.; Liu, S.Y.; Li, X.Q.; Zhou, Y.L.; Fan, J.R.; Li, L.H.; An, D.G. Molecular cytogenetic identification of a new wheat-rye 6R addition line and physical localization of its powdery mildew resistance gene. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 889494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.L.; Zhao, H.M.; Li, Y.; Wu, R.X.; Liu, G.B. Breeding of new forage triticale ‘Jisi No.3′ with stress resistance and high yield. Acta Agrestia. Sin. 2020, 28, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.W.; Han, G.H.; Gu, T.T.; Shi, Z.P.; Cao, L.J.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, C.L.; Zhuo, S.Y.; Li, L.H.; et al. Cytogenetic characterization of a novel wheat-rye 2R (2D) substitution line YT9 conferring powdery mildew resistance from the three-leaf stage and physical mapping of PmYT9. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2025, 138, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.L.; Ben, Y.X.; Wang, T.C.; Xu, X.L.; Xue, X. Some problems involved in the cross between octoploid and hexaploid forms of triticale. Acta Agron. Sin. 1988, 14, 104–109. [Google Scholar]

- Facchini, N.; Morcia, C.; Terzi, V.; Rizza, F.; Badeck, F.W. Triticale in Italy. Biology 2023, 12, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouafiane, M.; Ameur-Zaimeche, O.; Mehda, S.; Touil, S.; Heddam, S.; Cimmino, A. Evaluating salinity stress tolerance of a novel triticale genotype: Wheat crop improvement for arid agroecosystems. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Appl. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golebiowska-Paluch, G.; Dyda, M. The genome regions associated with abiotic and biotic stress tolerance, as well as other important breeding traits in triticale. Plants 2023, 12, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrka, M.; Chełkowski, J. Enhancing the resistance of triticale by using genes from wheat and rye. J. Appl. Genet. 2004, 45, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zou, J.W.; Zhang, S.S.; Zhang, Z.W.; Ren, X.; Sun, H.; Hu, T.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, X. Breeding and identification of stripe rust resistant line HB20121023 derived from wheat-octoploid triticale hybrid. Seed 2016, 35, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.H.; Ji, W.Q.; Li, F.Z. Advances in application of rye for wheat improvement. J. Triticeae Crops 2005, 25, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.J.; Arterburn, M.; Jones, S.S.; Murray, T.D. Resistance to eyespot of wheat, caused by Tapesia yallundae, derived from Thinopyrum intermedium homoeologous group 4 chromosome. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2005, 111, 932–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.J.; Cui, L.; Li, H.L.; Wang, X.M.; Murray, T.D.; Conner, R.L.; Wang, L.J.; Gao, X.; Sun, Y.; Sun, S.C.; et al. Effective resources in wheat and wheat–Thinopyrum derivatives for resistance to Heterodera filipjevi in China. Crop Sci. 2012, 52, 1209–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.J.; Wang, X.M. Thinopyrum ponticum and Th. intermedium: The promising source of resistance to fungal and viral diseases of wheat. J. Genet. Genom. 2009, 36, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.S.; Huang, D.H.; Du, L.P.; Ye, X.G.; Xin, Z.Y. Identification of wheat–Thinopyrum intermedium 2Ai-2 ditelosomic addition and substitution lines with resistance to barley yellow dwarf virus. Plant Breed. 2006, 125, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Zhang, S.X.; Wang, H.; Shi, Y.; Li, Z.Q.; Zhu, L.; Song, W.F.; Yang, X.F.; Song, Q.J.; Li, X.L.; et al. Genetic improvement and genomics-assisted breeding of the germplasm resource Thinopyrum intermedium. J. Plant Genet. Resour. 2020, 21, 1385–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.K.; Duan, W.J.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, J.W.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, M.; Yan, Y.M. 2D-DIGE based proteome analysis of wheat-Thinopyrum intermedium 7XL/7DS translocation line under drought stress. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.R.; Chen, Q.H.; Jiang, W.N.; Zhang, A.H.; Yang, E.N.; Yang, Z.J. Molecular and cytogenetic identification of wheat-Thinopyrum intermedium double substitution line-derived progenies for stripe rust resistance. Plants 2023, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Friebe, B.; Gill, B.S. Recent advances in alien gene transfer in wheat. Euphytica 1993, 73, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.Y.; Zeng, J.; Xie, Q.; Tao, S.; Zhong, M.Y.; Zhang, H.Q.; Fan, X.; Sha, L.N.; Xu, L.L.; Zhou, Y.H. Molecular cytogenetic characterization and stripe rust response of a trigeneric hybrid involving Triticum, Psathyrostachys and Thinopyrum. Genome 2012, 55, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.Y.; Gao, J.D.; Liu, J.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, W.; Yang, X.; Song, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y. Identification of new trigeneric hybrid materials from progeny of Thinopyrum-wheat and triticale. J. Agric. Biotechnol. 2017, 25, 547–557. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H.Y.; Zhong, M.Y.; Xie, Q.; Zhang, H.Q.; Fan, X.; Sha, L.N.; Xu, L.L.; Zhou, Y.H. Production and cytogenetics of trigeneric hybrid involving Triticum, Psathyrostachys and Secale. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2012, 59, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Zhang, A.M.; Wang, Z.G.; Wang, J.; Wei, Z.; Liu, D.C.; Li, J.M. A wheat-Thinopyrum ponticum-rye trigeneric germplasm line with resistance to powdery mildew and stripe rust. Euphytica 2012, 188, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosina, R.; Heslop-Harrison, J.S. Molecular cytogenetics of an amphiploid trigeneric hybrid between Triticum durum, Thinopyrum distichum and Lophopyrum elongatum. Ann. Bot. 1996, 78, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fradkin, M.; Greizerstein, E.J.; Grassi, E.; Ferreira, V.; Ferrari, M.R.; Poggio, L. Cytogenetic analysis of meiotic behaviour and stability in a trigeneric hybrid (triticale × trigopiro). Protoplasma 2024, 261, 1221–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.Y.; Huang, J.; Zhu, W.; Li, D.Y.; Diao, C.D.; Tang, L.; Wang, Y.; Xu, L.L.; Zeng, J.; Fan, X.; et al. Cytogenetic behavior of trigeneric hybrid progeny involving wheat, rye and Psathyrostachys huashanica. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2016, 148, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.Y.; Tang, L.; Li, D.Y.; Diao, C.D.; Zhu, W.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fan, X.; Xu, L.L.; Zeng, J.; et al. Cytogenetic study and stripe rust response of the derivatives from a wheat-Thinopyrum intermedium-Psathyrostachys huashanica trigeneric hybrid. Genome 2017, 60, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.B.; Lang, T.; Li, B.; Yu, Z.H.; Wang, H.J.; Li, G.R.; Yang, E.N.; Yang, Z.J. Introduction of Thinopyrum intermedium ssp. trichophorum chromosomes to wheat by trigeneric hybridization involving Triticum, Secale and Thinopyrum genera. Planta 2017, 245, 1121–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.Y.; Tang, Y.Q.; Yao, L.S.; Wu, H.; Tu, X.Y.; Zhuang, L.F.; Qi, Z.J. Molecular cytogenetic characterization of a novel multiplex oligonucleotide probe for efficient identification of wheat-Thinopyrum bessarabicum chromatin. Mol. Breed. 2019, 39, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.P.; Jiang, B.; Li, Y.X.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y. Molecular cytogenetic detection of trigeneric hybrid progeny in wheat. Mol. Plant Breed. 2013, 11, 163–167. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, W.; Jin, X.; Jiang, B.; Qi, X.Y.; Chen, Y.X.; Li, X.L.; Liu, X.Q.; Ren, Y.K.; Cui, L.; Song, Q.J.; et al. Development and molecular cytogenetic characterization of cold-hardy perennial wheatgrass adapted to northeastern China. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, R.Y.; Xiao, Z.M.; Li, J.L. Screening of universal specific DNA probes for rye. J. Triticeae Crops 2007, 27, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.J.; Arterburn, M.; Jones, S.S.; Murray, T.D. A new source of resistance to Tapesia yallundae associated with a homoeologous group 4 chromosome in Thinopyrum ponticum. Phytopathology 2004, 94, 932–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Z.; Song, W.S.; Song, A.N.; Wu, C.F.; Ding, J.R.; Yu, X.N.; Song, J.; Liu, M.M.; Yang, X.Y.; Jiang, C.T.; et al. Improvement of agronomic performances in cold weather conditions for perennial wheatgrass by crossing Thinopyrum intermedium with wheat-Th. intermedium partial amphiploids. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1207078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.J.; Doyle, J.L. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 1987, 19, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.Y.; Zhang, Z.M.; Ding, J.R.; Wu, C.F.; Qu, Y.F.; Song, A.N.; Zhao, H.B.; Song, W.W.; Liu, M.; Yang, D.H.; et al. Cytogenetics and genomics analysis of cold-hardy perennial wheatgrass: Insights into agronomic performance, chromosome composition, and gene expression. Plant J. 2025, 122, e70179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.X.; Yang, Z.J.; Fu, S.L. Oligonucleotides replacing the roles of repetitive sequences pAs1, pSc119.2, pTa-535, pTa71, CCS1, and pAWRC.1 for FISH analysis. J. Appl. Genet. 2014, 55, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.L.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y.Y.; Li, M.; Yang, Z.J.; Qiu, L.; Yan, B.J.; Ren, Z.L.; Tang, Z.X. Oligonucleotide probes for ND-FISH analysis to identify rye and wheat chromosomes. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGoverin, C.M.; Snyders, F.; Muller, N.; Botes, W.; Fox, G.; Manley, M. A review of triticale uses and the effect of growth environment on grain quality. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 1155–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzato, E.; Laudadio, V.; Tufarelli, V. Effects of harvest period, nitrogen fertilization and mycorrhizal fungus inoculation on triticale (×Triticosecale Wittmack) forage yield and quality. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2012, 27, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, V.S.; Juskiw, P.E.; Aljarrah, M. Triticale as a forage. In Triticale; Eudes, F., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.W.; Feng, H.; Yang, G.T.; Li, H.W.; Fu, S.L.; Li, B.; Li, Z.S.; Zheng, Q. Establishment and identification of six wheat-Thinopyrum ponticum disomic addition lines derived from partial amphiploid Xiaoyan 7430. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 135, 3277–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, B.W.; Gao, J.; Yao, Z.J.; Zhu, W.; Xu, L.L.; Cheng, Y.R.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, J.; Fan, X.; Sha, L.N.; et al. Development and identification of wheat–Psathyrostachys huashanica 7NsS small segment translocation lines with early heading date gene Ehd-7Ns. Crop. J. 2025, 13, 1186–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, B.R.; Zhang, H.; Lu, Y.X.; Chen, L.F.; Zhu, W.; Xu, L.L.; Wu, D.D.; Cheng, Y.R.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, J.; et al. Fine mapping of the all-stage stripe rust resistance gene Yr4EL and its utilization in wheat resistance breeding. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 49, 1064–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, M.; Rouse, M.N.; Bajgain, P.; Danilova, T.V.; Motsnyi, I.; Steffenson, B.J.; Patpour, M.; Rahmatov, M. Identification and characterization of Sr59-mediated stem rust resistance in a novel wheat-rye translocation T2BL·2BS-2RL. Crop. J. 2025, 13, 909–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilperte, V.; Boehm, R.; Debener, T. A highly mutable GST is essential for bract colouration in Euphorbia pulcherrima Willd. Ex Klotsch. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.Z.; Duan, L.; Sun, M.H.; Yang, Z.; Li, H.Y.; Hu, K.M.; Yang, H.; Liu, L. Current trends and insights on EMS mutagenesis application to studies on plant abiotic stress tolerance and development. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1052569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, M.; Gaál, E.; Farkas, A.; Molnár, I.; Bartoš, J.; Doležel, J.; Cabrera, A.; Endo, T.R. Gametocidal genes: From a discovery to the application in wheat breeding. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1396553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Zhao, H.B.; Zhang, Y.M.; Li, X.L. Research progress on trigeneric hybridization in cereal crops. Mol. Plant Breed. 2020, 18, 7530–7536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Liu, H.Y.; Wang, H.G.; Li, X.F. Chromosome behavior during microsporogenesis in trigeneric hybrid F1 of Triticeae. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 41, 335–339. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.Y.; Long, D.; Li, T.H.; Wu, Y.L.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, J.; Xu, L.L.; Fan, X.; Sha, L.N.; Zhang, H.Q.; et al. Cytogenetics and stripe rust resistance of wheat-Thinopyrum elongatum hybrid derivatives. Mol. Cytogenet. 2018, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.Y.; Du, H.N.; Su, F.Y.; Wang, J.; Meng, Q.F.; Liu, T.L.; Guo, R.; Chen, Z.Z.; Li, H.H.; Liu, W.X.; et al. Molecular cytogenetic analyses of two new wheat-rye 6RL translocation lines with resistance to wheat powdery mildew. Crop. J. 2023, 11, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.Z.; Han, G.H.; Gong, W.P.; Han, R.; Wang, X.L.; Bao, Y.G.; Li, J.B.; Liu, A.F.; Li, H.S.; Liu, J.J.; et al. Development and characterization of a novel wheat-rye T2DS·2DL-2RL translocation line with high stripe rust resistance. Phytopathol. Res. 2024, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.R.-C.; Larson, S.R.; Jensen, K.B.; Bushman, B.S.; DeHaan, L.R.; Wang, S.W.; Yan, X.B. Genome evolution of intermediate wheatgrass as revealed by EST-SSR markers developed from its three progenitor diploid species. Genome 2015, 58, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Cheng, S.W.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, S.X.; Yan, W.; Song, W.F.; Yang, X.F.; Song, Q.J.; Jang, B.; Qi, X.Y.; et al. Molecular cytogenetic characterization and fusarium head blight resistance of five wheat-Thinopyrum intermedium partial amphiploids. Mol. Cytogenet. 2021, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; Cui, F.; Wang, H. Molecular cytogenetic characterization of a new wheat-Thinopyrum intermedium partial amphiploid resistant to powdery mildew and stripe rust. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2009, 126, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.T.; Zhang, N.; Boshoff, W.H.P.; Li, H.W.; Li, B.; Li, Z.S.; Zheng, Q. Identification and introgression of a novel leaf rust resistance gene from Thinopyrum intermedium chromosome 7Js into wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2023, 136, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.F.; Zhao, X.Y.; Li, M.Y.; Qu, Y.F.; Yan, X.Y.; Ding, J.R.; Zhou, T.; Jiang, C.Y.; Liu, Q.H.; Jiang, J.R.; et al. Development and molecular cytogenetic characterization of black-grain wheat derived from wheat-Thinopyrum intermedium hybridization. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2025, 138, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (A) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lines | Plant Height (cm) | Spike Length (cm) | Spikelet Number per Spike | Floret Number | ||||

| 2023 | 2024 | 2023 | 2024 | 2023 | 2024 | 2023 | 2024 | |

| 4280-2 | 115.2 f | 154.7 b | 12.38 b | 11.3 de | 25 f | 25 f | 5 a | 5 a |

| 4283-2 | 112.8 g | 143.0 d | 10.4 de | 10.6 ef | 26 ef | 26 ef | 5 a | 4 b |

| 4284-2 | 144.8 b | 123.0 e | 11.3 de | 10.5 ef | 27 de | 27 de | 4 b | 4 b |

| 4290-2 | 150.0 a | 158.7 a | 12.1 bc | 13.2 b | 28 cd | 28 cd | 5 a | 5 a |

| 4292-2 | 121.5 d | 148.6 c | 12.5 b | 12.5 bc | 29 bc | 29 bc | 5 a | 4 b |

| 4295-1 | 121.6 d | 147.9 c | 10.5 de | 11.9 cd | 30 ab | 30 ab | 4 b | 4 b |

| Hashi 209 | 120.5 e | 153.6 c | 10.3 e | 10.1 f | 31 a | 31 a | 4 b | 4 b |

| Maicao 8 | 129.4 c | 142.1 d | 15.4 a | 17.7 a | 16 g | 19 f | 3 c | 3 c |

| (B) | ||||||||

| Lines | Tiller Number per Plant | Thousand-Grain Weight (g) | Protein Content (%) | |||||

| 2023 | 2024 | 2023 | 2024 | 2023 | 2024 | |||

| 4280-2 | 8 e | 12 bc | 37.5 c | 35.2 b | 13.1 d | 13.8 d | ||

| 4283-2 | 13 c | 10 de | 34.9 f | 34.0 c | 13.3 c | 14.3 d | ||

| 4284-2 | 8 e | 14 a | 38.2 bc | 35.1 b | 13.7 b | 14.8 b | ||

| 4290-2 | 14 b | 11 cd | 38.1 b | 35.9 a | 13.0 d | 14.5 c | ||

| 4292-2 | 17 a | 13 ab | 36.4 d | 33.9 c | 12.8 d | 13.4 d | ||

| 4295-1 | 13 c | 12 bc | 38.5 a | 32.6 d | 13.9 b | 14.9 b | ||

| Hashi 209 | 10 d | 9 e | 37.8 c | 34.9 b | 11.2 e | 12.2 e | ||

| Maicao 8 | 8 e | 9 e | 29.4 g | 32.6 d | 17.8 a | 20.1 a | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jiang, C.; He, M.; Yan, X.; Xing, Q.; Qu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Jin, H.; Zhang, R.; Du, R.; Kong, D.; et al. Development and Characterization of Novel St-R Translocation Triticale from a Trigeneric Hybrid. Agronomy 2026, 16, 336. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030336

Jiang C, He M, Yan X, Xing Q, Qu Y, Zhao H, Jin H, Zhang R, Du R, Kong D, et al. Development and Characterization of Novel St-R Translocation Triticale from a Trigeneric Hybrid. Agronomy. 2026; 16(3):336. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030336

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Changtong, Miao He, Xinyu Yan, Qianyu Xing, Yunfeng Qu, Haibin Zhao, Hui Jin, Rui Zhang, Ruonan Du, Deyu Kong, and et al. 2026. "Development and Characterization of Novel St-R Translocation Triticale from a Trigeneric Hybrid" Agronomy 16, no. 3: 336. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030336

APA StyleJiang, C., He, M., Yan, X., Xing, Q., Qu, Y., Zhao, H., Jin, H., Zhang, R., Du, R., Kong, D., Yang, K., Song, A., Li, X., Li, H., Cui, L., & Zhang, Y. (2026). Development and Characterization of Novel St-R Translocation Triticale from a Trigeneric Hybrid. Agronomy, 16(3), 336. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030336