Physiological Mechanisms of Nano-CeO2 and Nano-TiO2 as Seed-Priming Agents in Enhancing Drought Tolerance of Barley Seedlings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.2. Seed Priming Treatment

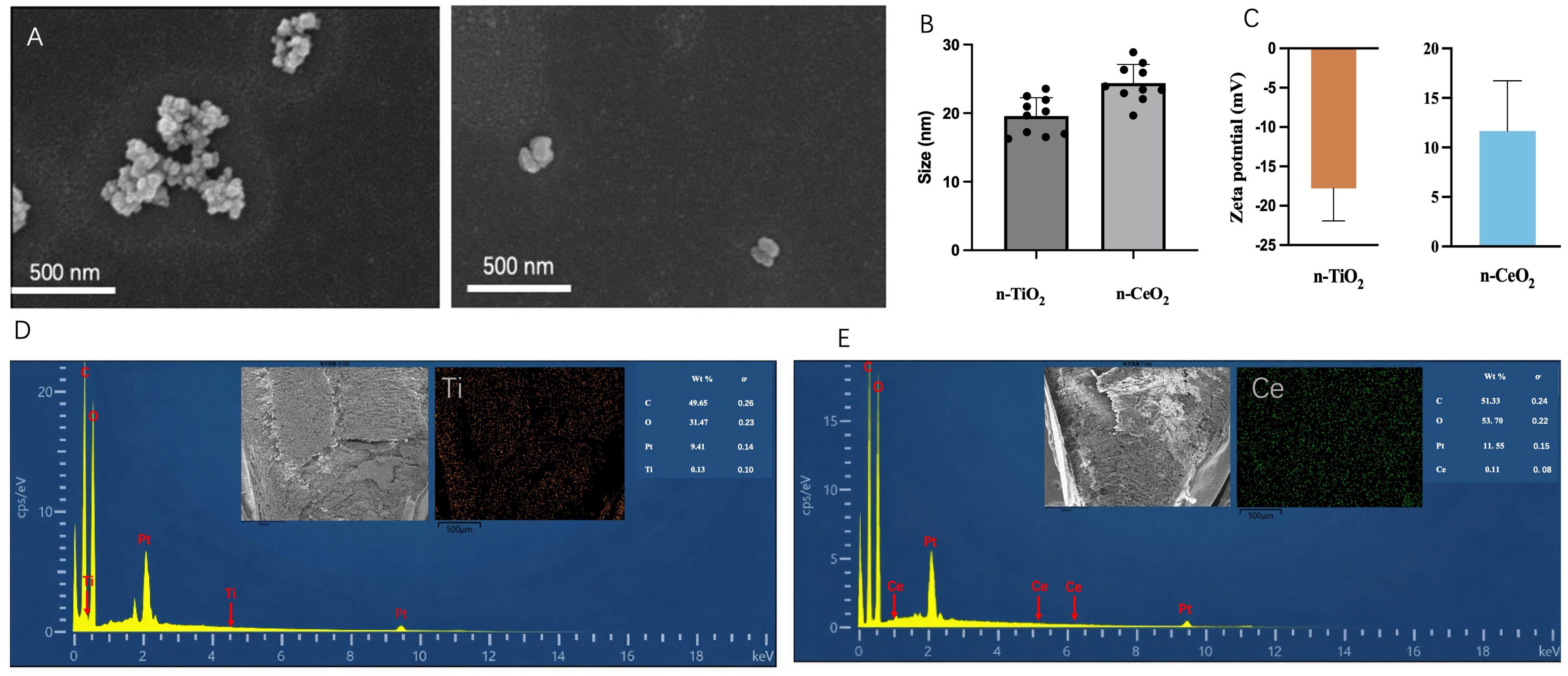

2.3. Characterization of Nanoparticles and Analysis of Seed Interaction

2.4. Seed Water Absorption Test

2.5. Germination Test

2.6. Determination of Physiological Indices

2.7. Data Processing

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Nanoparticles

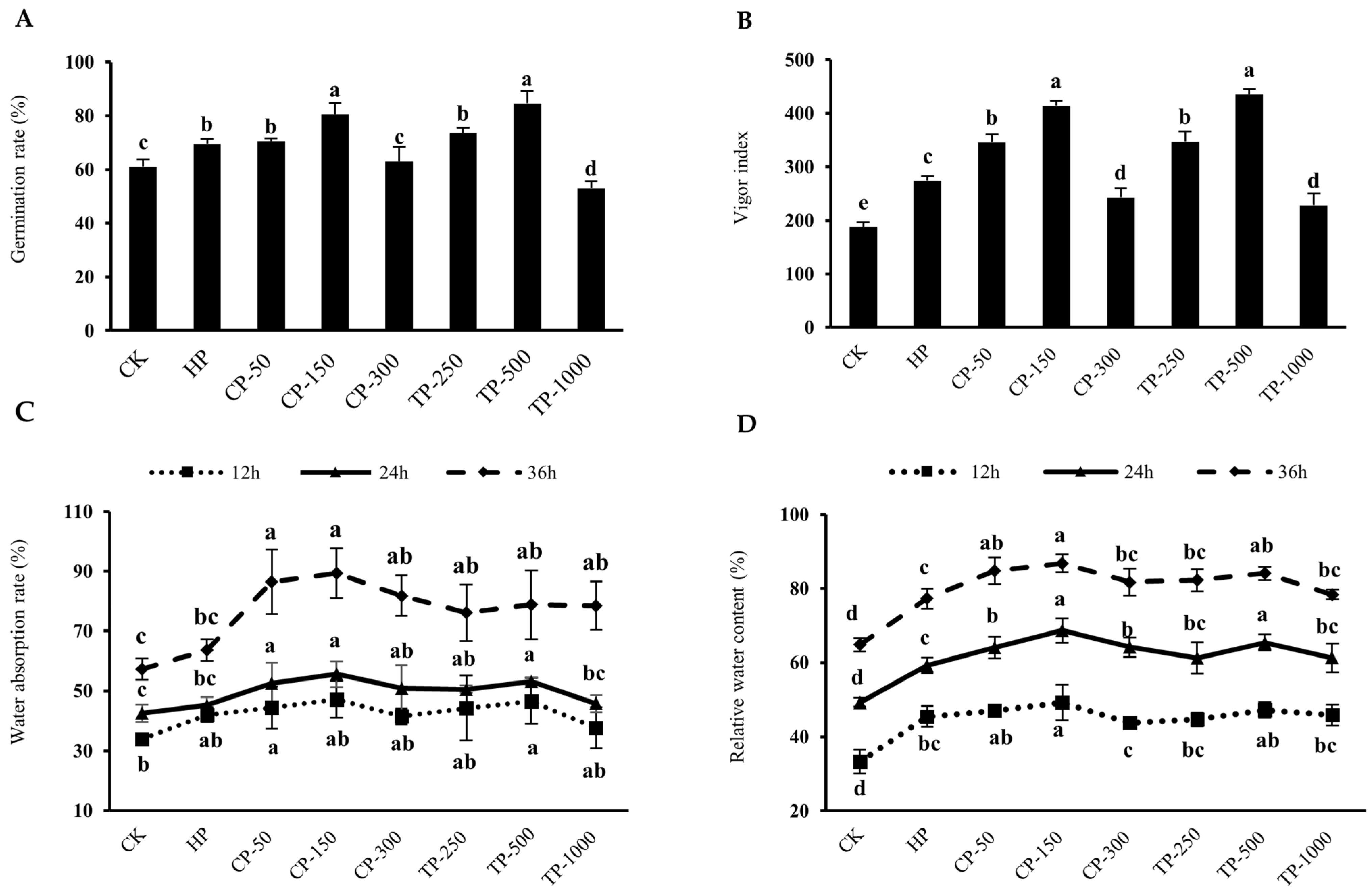

3.2. Effects of Nano-Priming on Seed Germination and Early Seedling Growth (Concentration Screening)

3.2.1. Seed Germination Indices, Water Uptake Rate, and Relative Moisture Content

3.2.2. Seedling Growth and Biomass Accumulation

3.3. Physiological Effects of Nano-Priming on Seed Germination Under Drought Stress

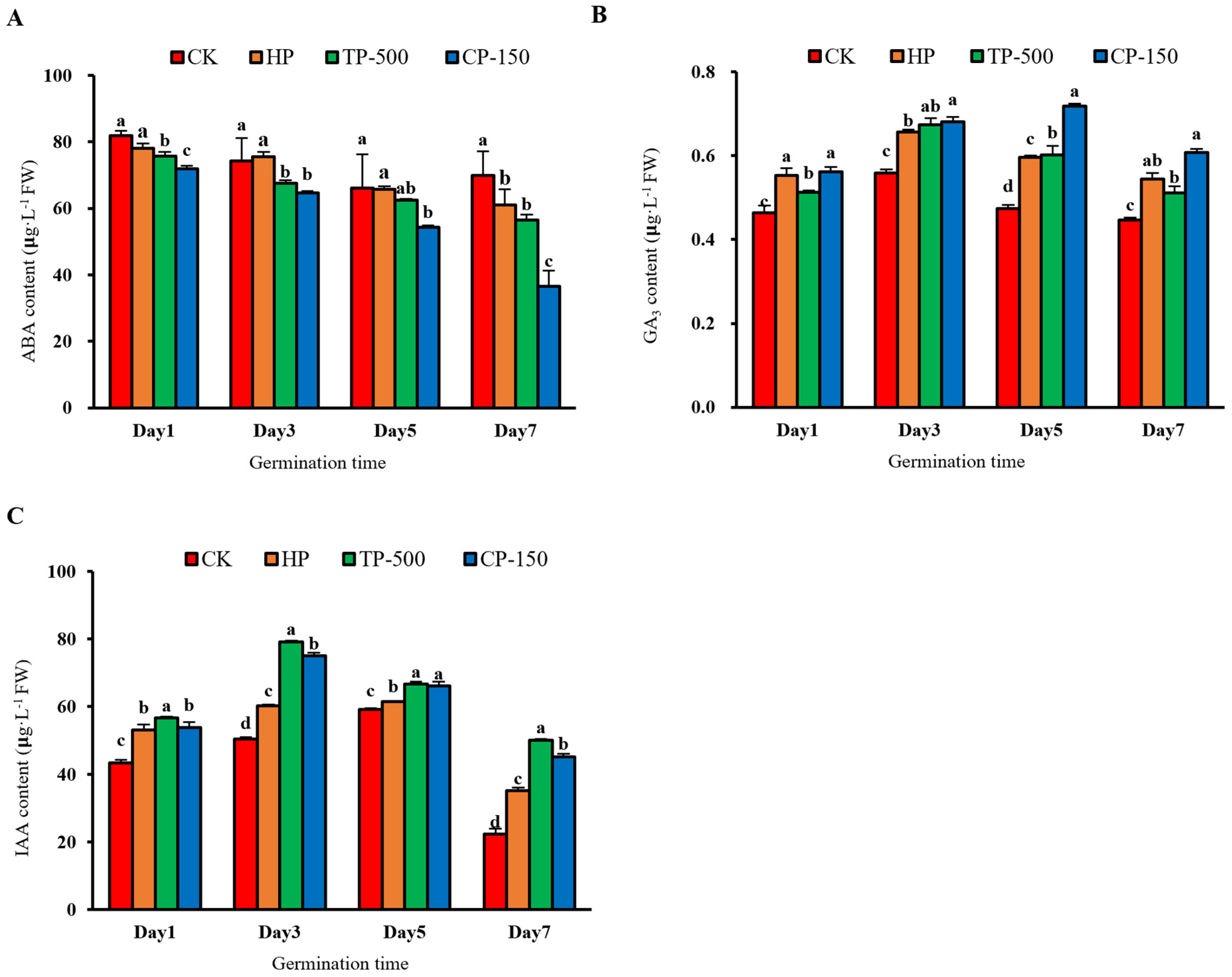

3.3.1. Endogenous Hormones

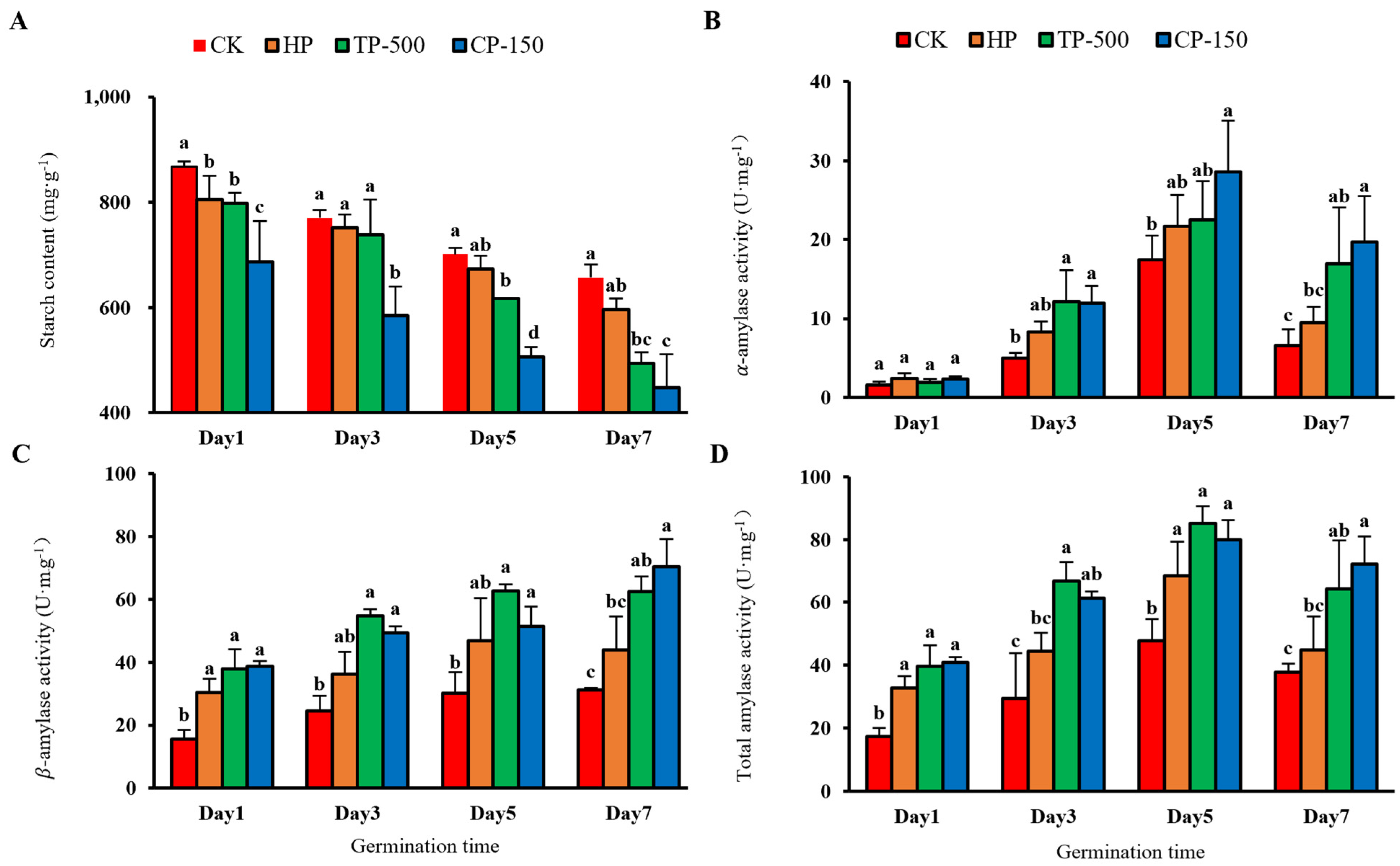

3.3.2. Starch Metabolism and Amylase Activity

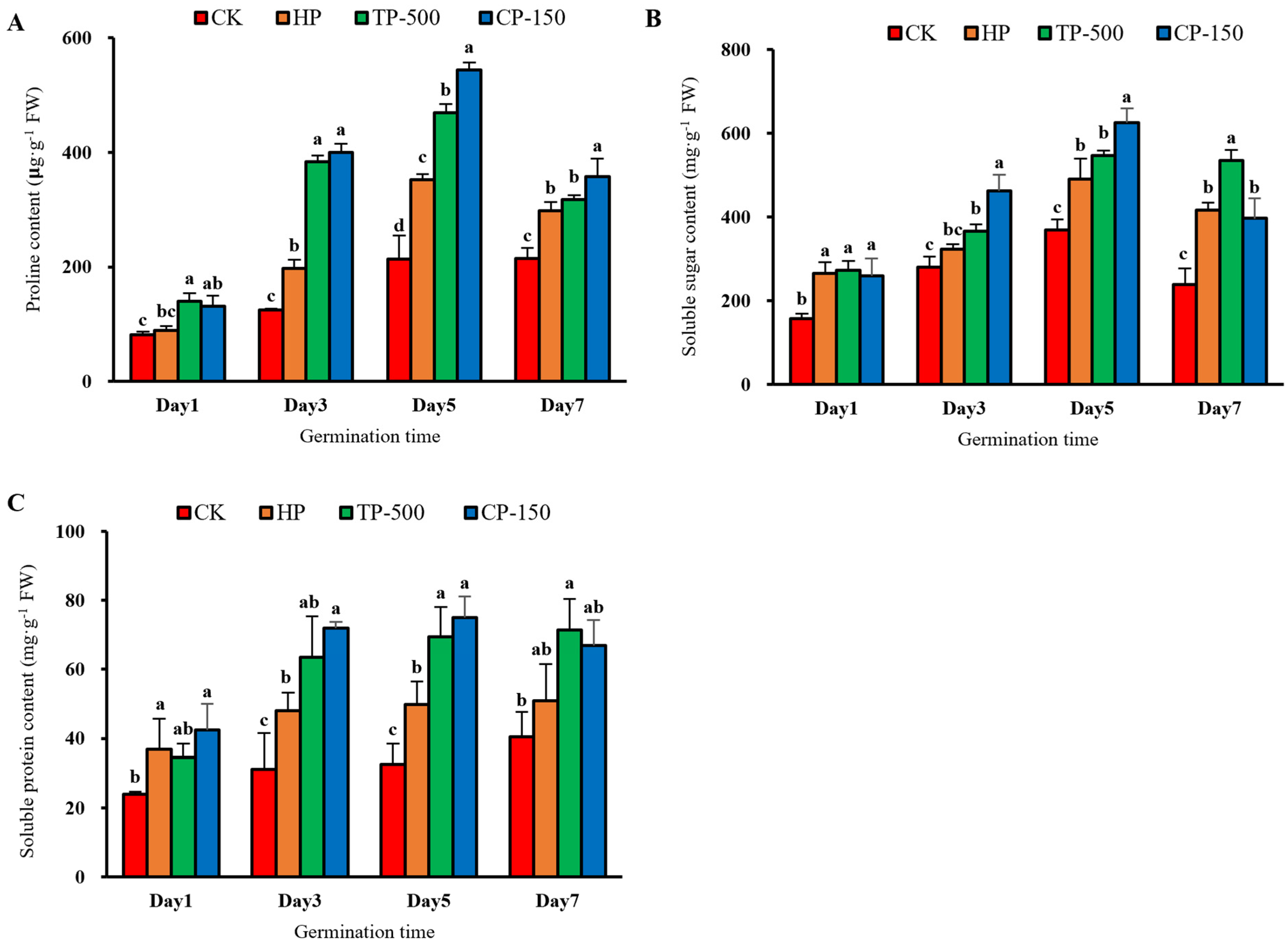

3.3.3. Osmotic Adjustment Substances

3.4. Physiological Effects of Nano-Priming on Barley Seedlings Under Drought Stress

3.4.1. Photosynthetic Pigments

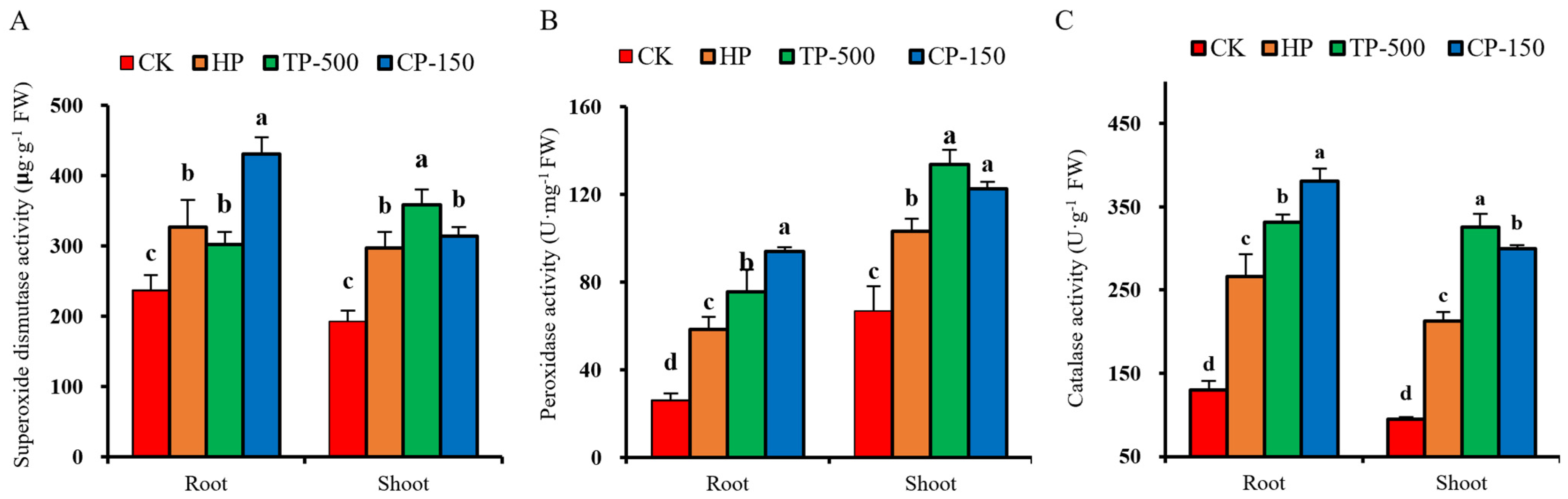

3.4.2. Antioxidant Enzyme Activity

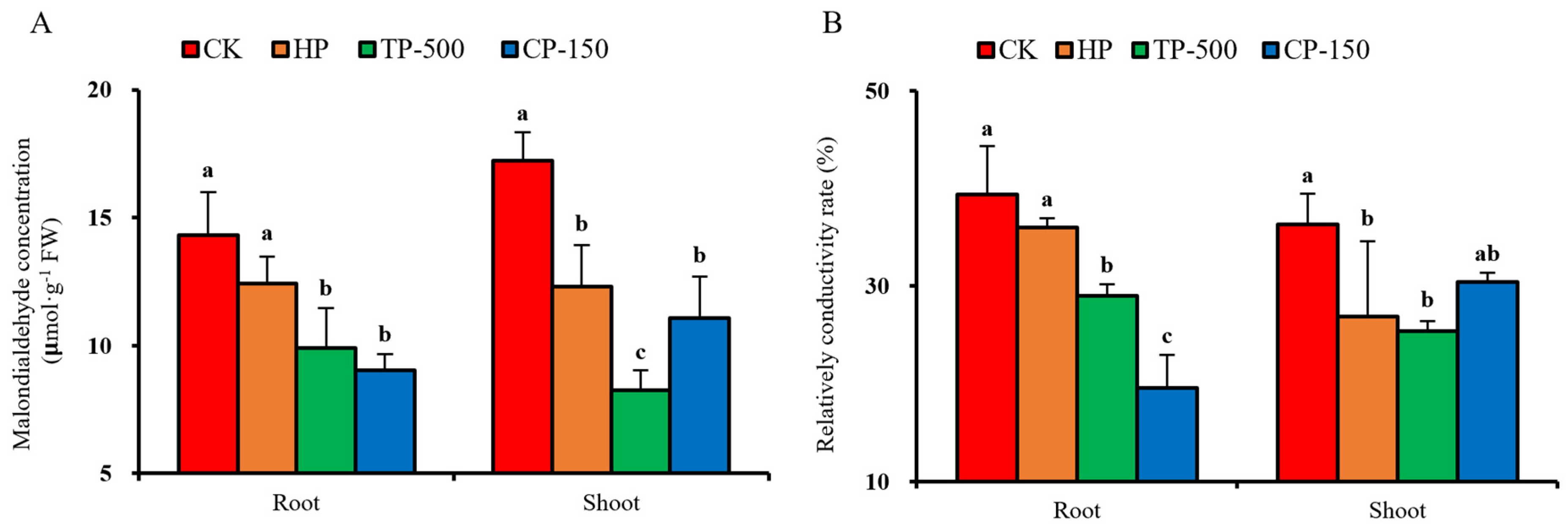

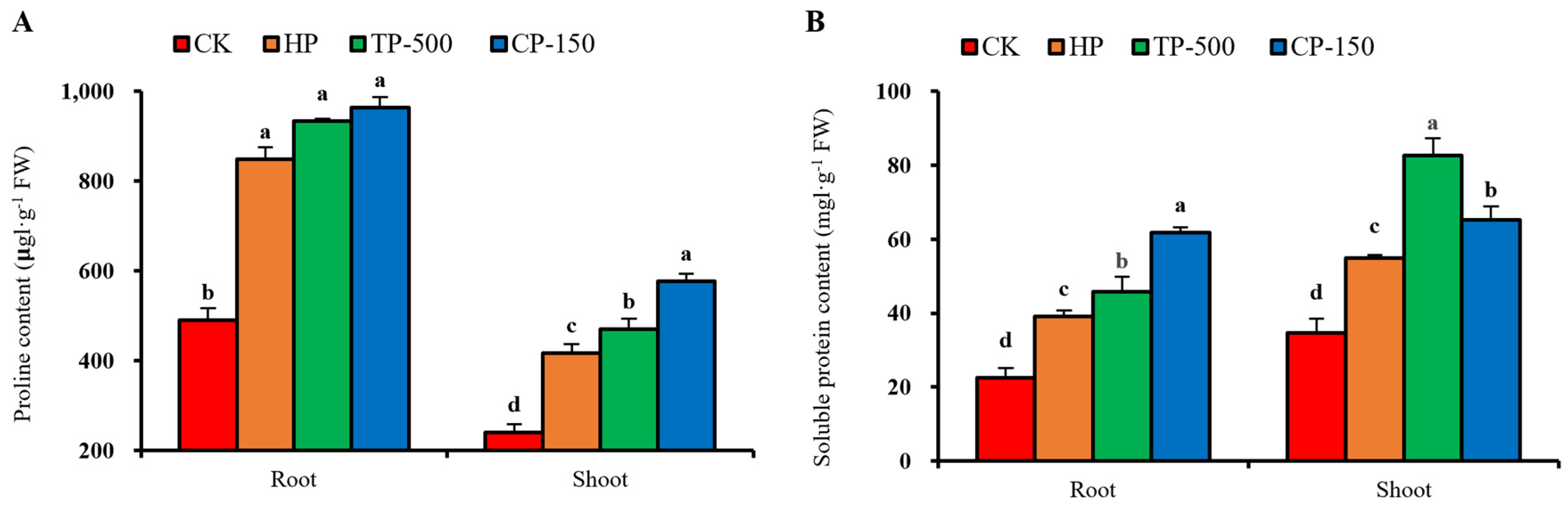

3.4.3. Membrane Stability and Osmoregulatory Substances

4. Discussion

4.1. Nano-Priming Treatment Promotes Seed Germination and Seedling Growth

4.2. Nano-Priming Modulates Key Physiological Processes in a Material-Specific Manner

4.3. Nano-Priming Enhances Photosynthetic Performance and Antioxidant Defense Capacity

4.4. Nano-Priming Enhances Membrane Stability and Osmoregulatory Capacity

4.5. Scientific Novelty, Application, and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdelrady, A.; Ma, Z.; Elshawy, E.E.; Wang, L.; Askri, S.M.H.; Ibrahim, Z.; Dennis, E.; Kanwal, F.; Zeng, F.; Shamsi, I.H. Physiological and biochemical mechanisms of salt tolerance in barley under salinity stress. Plant Stress 2024, 11, 100403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.J.; Shi, P.; Xiang, L.; He, Y.; Dong, Y.; Miao, Y.; Qi, J. Evaluation of barley genotypes for drought adaptability: Based on stress indices and comprehensive evaluation as criteria. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1436872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbari, M.; Sabouri, H.; Sajadi, S.J.; Yarahmadi, S.; Ahangar, L. Classification and prediction of drought and salinity stress tolerance in barley using GenPhenML. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bewley, J. Seed germination and dormancy. Plant Cell 1997, 9, 1055–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharya, P.; Jayaprakasha, G.K.; Crosby, K.M.; Jifon, J.L.; Patil, B.S. Nanoparticle-mediated seed priming improves germination, growth, yield, and quality of watermelons (Citrullus lanatus) at multi-locations in Texas. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espanany, A.; Fallah, S.; Tadayyon, A. Seed priming improves seed germination and reduces oxidative stress in black cumin (Nigella sativa) in presence of cadmium. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 79, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.F.; Ma, L.; Li, J.C.; Hou, D.; Zeng, B.; Zhang, L.; Liu, C.; Bi, Q.; Tan, J.; Yu, X. Factors influencing seed dormancy and germination and advances in seed priming technology. Plants 2024, 13, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, A.; Li, H.; Tahir, M.M.; Mahmood, A.; Nawaz, M.; Shah, A.N.; Aslam, M.T.; Negm, S.; Moustafa, M.; Hassan, M.U.; et al. The role of nanoparticles in plant biochemical, physiological, and molecular responses under drought stress: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 976179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.H.; Li, Z.H. Recent advances in nano-enabled agriculture for improving plant performance. Crop J. 2022, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imtiaz, H.; Shiraz, M.; Mir, A.R.; Siddiqui, H.; Hayat, S. Nano-Priming Techniques for Plant Physio-Biochemistry and Stress Tolerance. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 6870–6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Lu, L.; Wang, A.; Zhang, H.; Huang, M.; Wu, H.; Xing, B.; Wang, Z.; Ji, R. Nano-biotechnology in agriculture: Use of nanomaterials to promote plant growth and stress tolerance. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 1935–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelhameed, R.E.; Hegazy, H.S.; Abdalla, H.; Adarosy, M.H. Efficacy of green synthesized titanium dioxide nanoparticles in attenuation salt stress in Glycine max plants: Modulations in metabolic constituents and cell ultrastructure. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Hu, P.G.; Li, F.J.; Wu, H.H.; Shen, Y.; White, J.C.; Tian, X.L.; Li, Z.H.; Giraldo, J.P. Emerging investigator series: Molecular mechanisms of plant salinity stress tolerance improvement by seed priming with cerium oxide nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Nano 2020, 7, 2214–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boora, R.; Rani, N.; Kumari, S.; Goel, S.; Arya, A.; Grewal, S. Exploring the role of green synthesized cerium nanoparticles in enhancing wheat’s drought tolerance: A comprehensive study of biochemical parameters and gene expression. Cereal Res. Commun. 2024, 52, 1487–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleymani, S.; Piri, S.; Aazami, M.A.; Salehi, B. Cerium oxide nanoparticles alleviate drought stress in apple seedlings by regulating ion homeostasis, antioxidant defense, gene expression, and phytohormone balance. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Yang, M.; Miao, M. Influence of SiO2, Al2O3 and TiO2 nanoparticles on okra seed germination under PEG-6000 simulated water deficit stress. J. Seed Sci. 2023, 45, e202345274866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Li, T.; Chen, X.; Lan, R.; Pang, Z.; Wu, S.; Xiong, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Lu, H.; et al. Resistance mechanism of Abies beshanzuensis under heat stress was elucidated through the integration of physiological and transcriptomic analyses. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.G.; Gong, M. Comprehensive and Design-Oriented Experimental Tutorial in Plant Physiology; Huazhong University of Science and Technology Press: Wuhan, China, 2014; pp. 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Q.; Huang, T.; Zhou, C.; Wan, X.; He, X.; Miao, P.; Cheng, H.; Wang, X.; Yu, H.; Hu, M.; et al. Nano-priming with selenium nanoparticles reprograms seed germination, antioxidant defense, and phenylpropanoid metabolism to enhance Fusarium graminearum resistance in maize seedlings. J. Adv. Res. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heath, R.L.; Packer, L. Photoperoxidation in isolated chloroplasts: I. kinetics and stoichiometry of fatty acid peroxidation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1968, 125, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, S.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, P.; He, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Rui, Y.; et al. Fate and phytotoxicity of CeO2 nanoparticles on lettuce cultured in the potting soil environment. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Duan, M.; Xing, P.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, J.; Kong, L.; Tang, X. Effects of L-glutamic acid application on yield, grain quality, photosynthetic pigments, 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline, and antioxidant system of aromatic rice. Field Crops Res. 2023, 303, 109134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biju, S.; Fuentes, S.; Gupta, D. Silicon improves seed germination and alleviates drought stress in lentil crops by regulating osmolytes, hydrolytic enzymes and antioxidant defense system. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 119, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinifard, M.; Stefaniak, S.; Ghorbani, J.M.; Soltani, E.; Wojtyla, Ł.; Garnczarska, M. Contribution of exogenous proline to abiotic stresses tolerance in plants: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 3, 5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, R.; Rajput, V.D.; Ghodake, G.; Ahmad, F.; Meena, M.; Rehman, R.U.; Prasad, R.; Sharma, R.K.; Singh, R.; Seth, C.S. Comprehensive journey from past to present to future about seed priming with hydrogen peroxide and hydrogen sulfide concerning drought, temperature, UV and ozone stresses—A review. Plant Soil 2024, 500, 351–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabusta, M.; Szafrańska, K.; Posmyk, M.M. Exogenous melatonin improves antioxidant defense in cucumber seeds (Cucumis sativus L.) germinated under chilling stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizwan, M.; Ali, S.; Rehman, M.Z.; Malik, S.; Adrees, M.; Qayyum, M.F.; Alamri, S.A.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Ahmad, P. Effect of foliar applications of silicon and titanium dioxide nanoparticles on growth, oxidative stress, and cadmium accumulation by rice (Oryza sativa). Acta Physiol. Plant. 2019, 41, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshegaihi, R.M.; Saleem, M.H.; Saleem, A.; Ali, B.; Aziz, H.; Fahad, S.; Alataway, A.; Dewidar, A.Z.; Elansary, H.O. Silicon and titanium dioxide mitigate copper stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) through regulating antioxidant defense mechanisms. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 43, 1519–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, G.; Chen, L.; Gu, J.; Wu, H.; Li, Z. Cerium oxide nanoparticles improve cotton salt tolerance by enabling better ability to maintain cytosolic K+/Na+ ratio. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.N.; Li, Y.; Khan, Z.; Chen, L.; Liu, J.; Hu, J.; Wu, H.; Li, Z. Nanoceria seed priming enhanced salt tolerance in rapeseed through modulating ROS homeostasis and α-amylase activities. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.K.; Das, A.K.; Patel, M.K.; Shah, A.; Kumar, V.; Gantait, S. Engineered nanomaterials for plant growth and development: A perspective analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 630, 1413–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nile, S.H.; Thiruvengadam, M.; Wang, Y.; Samynathan, R.; Shariati, M.A.; Rebezov, M.; Nile, A.; Sun, M.; Venkidasamy, B.; Xiao, J.B.; et al. Nano-priming as emerging seed priming technology for sustainable agriculture—Recent developments and future perspectives. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahakham, W.; Sarmah, A.K.; Maensiri, S.; Theerakulpisut, P. Nanopriming technology for enhancing germination and starch metabolism of aged rice seeds using phytosynthesized silver nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdemir, H. Evaluation of transcription factor and aquaporin gene expressions in response to Al2O3 and ZnO nanoparticles during barley germination. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 166, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurel, C.; Boursiac, Y.; Luu, D.-T.; Santoni, V.; Shahzad, Z.; Verdoucq, L. Aquaporins in plants. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 1321–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.G.; Sun, G.Y.; Li, G.L.; Hu, G.H.; Fu, L.X.; Hu, S.X.; Yang, J.F.; Wang, Z.G.; Gu, W.R. Effects of multi walled carbon nanotubes and nano-SiO2 on key enzymes for seed germination and endogenous hormone level in maize seedling. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Badri, A.M.; Batool, M.; Mohamed, I.A.A.; Wang, Z.; Wang, C.; Tabl, K.M.; Khatab, A.; Kuai, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, B.; et al. Mitigation of the salinity stress in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) productivity by exogenous applications of bio-selenium nanoparticles during the early seedling stage. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 310, 119815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Ji, L.; Rico, C.; He, C.; Shakoor, I.; Fakunle, M.; Lu, X.H.; Xia, Y.; Hou, Y.; Hong, J. Transcriptomics reveals the pathway for increasing Brassica chinensis L. yield under foliar application of titanium oxide nanoparticles. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 18957–18970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Moreno, M.L.; de la Rosa, G.; Hernández-Viezcas, J.A.; Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS) corroboration of the uptake and storage of CeO2 nanoparticles and assessment of their differential toxicity in four edible plant species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 3689–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Zhao, C.; Wang, G.; Mao, Q.W.; Han, R. Cerium oxide nanoparticles alleviate enhanced UV-B radiation-induced stress in wheat seedling roots by regulating reactive oxygen species. Phyton-Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 94, 455–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Garay, A.; Pintos, B.; Manzanera, J.A.; Lobo, C.; Villalobos, N.; Martín, L. Uptake of CeO2 nanoparticles and its effect on growth of Medicago arborea in vitro plantlets. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2014, 161, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevik, S. TiO2 nanoparticles alleviates the effects of drought stress in tomato seedlings. Bragantia 2022, 82, e20220203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvar, M.; Azari, A.; Rahimi, A.; Maddah-Hosseini, S.; Ahmadi-Lahijani, M.J. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2-NPs) enhance drought tolerance and grain yield of sweet corn (Zea mays L.) under deficit irrigation regimes. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2022, 44, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Rico-Medina, A.; Caño-Delgado, A.I. The physiology of plant responses to drought. Science 2020, 368, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojjati, M.; Jahromi, M.G.; Abdossi, V.; Torkashvand, A.M. Exogenous melatonin modulated drought stress by regulating physio-biochemical attributes and fatty acid profile of sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.). J. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 43, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.Y.; Ma, C.X.; Hao, Y.; Jia, W.L.; Cao, Y.N.; Wu, H.H.; Xu, X.X.; Han, L.F.; Li, C.Y.; Shang, H.P.; et al. Molecular evidence of CeO2 nanoparticle modulation of ABA and genes containing ABA-responsive cis-elements to promote rice drought resistance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 21804–21816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.L.; Qiu, H.; Li, X.; He, E. Intergenerational transfer of nano-CeO2 in clonal strawberry and associated modulation of the hormonal network to enhance offspring ramet growth. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 23202–23215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, N.; Raja, N.I.; Ilyas, N.; Ikram, M.; Mashwani, Z.U.; Ehsan, M. Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress. Green Process. Synth. 2021, 10, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojjat, S.S.; Louis, G.H. TiO2 nanoparticle improve germination and seedling parameters and enhance tolerance of bitter vetch (Vicia ervilia L.) plants under salinity and drought stress. Nanobiotechnol. Rep. 2022, 17, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drebenstedt, I.; Schmid, I.; Poll, C.; Marhan, S.; Kahle, R.; Kandeler, E.; Högy, P. Effects of soil warming and altered precipitation patterns on photosynthesis, biomass production and yield of barley. J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 2020, 93, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandic, V.; Dodig, D.; Secanski, M.; Prodanovic, S.; Brankovic, G.; Titan, P. Grain yield, agronomic traits, and protein content of two- and six-row barley genotypes under terminal drought conditions. J. Cereal Sci. 2019, 79, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H.; Farhadi, H.; Morshedloo, M.R.; Maggi, F. Modeling and optimizing concentration of exogenous application of γ-aminobutyric acid on NaCl-stressed pineapple mint (Mentha suaveolens) using response surface methodology: An investigation into secondary metabolites and physiological parameters. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.X.; Xu, S.; Sun, M.Q.; Wei, H.; Muhammad, F.; Liu, L.Z.; Shi, G.L.; Gao, Y. Mn-doped cerium dioxide nanozyme mediates ROS homeostasis and hormone metabolic network to promote wheat germination under low-temperature conditions. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2025, 12, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, D.; Gupta, U.; Saha, S. Biosynthesized metal oxide nanoparticles for sustainable agriculture: Next-generation nanotechnology for crop production, protection and management. Nanoscale 2022, 149, 13950–13989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faraji, J.; Sepehri, A. Exogenous nitric oxide improves the protective effects of TiO2 nanoparticles on growth, antioxidant system and photosynthetic performance of wheat seedlings under drought stress. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020, 20, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adisa, I.O.; Pullagurala, V.L.; Rawat, S.; Hernandez-Viezcas, J.A.; Dimkpa, C.O.; Elmer, W.H.; White, J.C.; Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. Role of cerium compounds in Fusarium wilt suppression and growth enhancement in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 5959–5970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, H.; Adarosy, M.H.; Hegazy, H.S.; Abdelhameed, R.E. Potential of green synthesized titanium dioxide nanoparticles for enhancing seedling emergence, vigor and tolerance indices and DPPH free radical scavenging in two varieties of soybean under salinity stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, A.; Siddiqui, Z.A. Foliar spray and seed priming of titanium dioxide nanoparticles and their impact on the growth of tomato, defense enzymes and some bacterial and fungal diseases. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2022, 55, 527–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei, M.J.; Ebrahimi, A.; Heidari, P.; Azadvari, E.; Gharanjik, S.; Chaghakaboodi, Z. Titanium dioxide -mediated regulation of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants, pigments, and diosgenin content promotes cold stress tolerance in Trigonella foenum-graecum L. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.J.; Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Varela-Ramirez, A.; Castillo-Michel, H.; Li, C.Q.; Zhang, J.; Aguilera, R.J.; Keller, A.A.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. Effect of surface coating and organic matter on the uptake of CeO2NPs by corn plants grown in soil: Insight into the uptake mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 225–226, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karami, A.; Sepehri, A. Nano titanium dioxide and nitric oxide alleviate salt induced changes in seedling growth, physiological and photosynthesis attributes of barley. Zemdirb. Agric. 2018, 105, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Charagh, S.; Abbas, S.; Hassan, M.U.; Saeed, F.; Haider, S.; Sharif, R.; Anand, A.; Corpas, F.J.; Jin, W.; et al. Assessment of proline function in higher plants under extreme temperatures. Plant Biol. 2023, 25, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, L.; Zhang, W.L.; Schwab, A.P.; Ma, X.X. Uptake, accumulation, and in planta distribution of coexisting cerium oxide nanoparticles and cadmium in Glycine max (L.) Merr. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 12815–12824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarkina, R.; Makeeva, A.; Mamaeva, A.; Kovalchuk, S.; Ganaeva, D.; Tikhonovich, I.; Fesenko, I. The proteomic and peptidomic response of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) to drought Stress. Plants 2025, 14, 2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seleiman, M.F.; Al-Suhaibani, N.; Ali, N.; Akmal, M.; Alotaibi, M.; Refay, Y.; Dindaroglu, T.; Abdul-Wajid, H.H.; Battaglia, M.L. Drought stress impacts on plants and different approaches to alleviate its adverse effects. Plants 2021, 10, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osmolovskaya, N.; Shumilina, J.; Kim, A.; Didio, A.; Grishina, T.; Bilova, T.; Keltsieva, O.A.; Zhukov, V.; Tikhonovich, I.; Tarakhovskaya, E. Methodology of drought stress research: Experimental setup and physiological characterization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 4089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Treatment | Root Length (cm) | Shoot Length (cm) | Shoot Fresh Weight (g) | Root Fresh Weight (g) | Shoot Dry Weight (g) | Root Dry Weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 4.52 ± 0.12 e | 4.72 ± 0.12 d | 1.53 ± 0.10 d | 1.89 ± 0.04 ef | 0.10 ± 0.01 e | 0.24 ± 0.01 d |

| HP | 5.35 ± 0.17 c | 5.88 ± 0.11 c | 2.02 ± 0.12 b | 2.06 ± 0.09 cd | 0.20 ± 0.01 c | 0.28 ± 0.08 bc |

| CP-50 | 5.98 ± 0.31 b | 6.39 ± 0.14 b | 1.95 ± 0.11 bc | 2.19 ± 0.04 b | 0.23 ± 0.02 b | 0.27 ± 0.02 c |

| CP-150 | 6.53 ± 0.20 a | 6.51 ± 0.23 b | 2.10 ± 0.09 ab | 2.43 ± 0.11 a | 0.24 ± 0.01 b | 0.33 ± 0.01 a |

| CP-300 | 5.33 ± 0.19 c | 5.59 ± 0.26 c | 1.82 ± 0.13 c | 1.96 ± 0.11 de | 0.18 ± 0.01 d | 0.22 ± 0.02 d |

| TP-250 | 5.43 ± 0.16 c | 6.67 ± 0.24 b | 1.92 ± 0.05 bc | 2.10 ± 0.10 bc | 0.24 ± 0.01 b | 0.29 ± 0.03 b |

| TP-500 | 5.86 ± 0.14 b | 7.09 ± 0.11 a | 2.23 ± 0.19 a | 2.36 ± 0.09 a | 0.27 ± 0.01 a | 0.28 ± 0.01 bc |

| TP-1000 | 4.92 ± 0.25 d | 5.78 ± 0.34 c | 1.64 ± 0.11 d | 1.77 ± 0.09 f | 0.19 ± 0.00 cd | 0.27 ± 0.01 c |

| Treatment | Chlorophyll a (mg·g−1) | Chlorophyll b (mg·g−1) | Total Chlorophyll Content (mg·g−1) | Carotenoid (mg·g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 0.26 ± 0.13 c | 0.62 ± 0.03 c | 0.88 ± 0.16 b | 0.14 ± 0.03 b |

| HP | 0.47 ± 0.14 bc | 0.70 ± 0.08 b | 1.17 ± 0.20 b | 0.19 ± 0.02 ab |

| CP-150 | 0.75 ± 0.11 a | 1.08 ± 0.02 a | 1.83 ± 0.12 a | 0.33 ± 0.12 a |

| TP-500 | 0.75 ± 0.07 a | 0.87 ± 0.05 ab | 1.58 ± 0.22 ab | 0.35 ± 0.13 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ye, X.; Song, R.; Qi, J. Physiological Mechanisms of Nano-CeO2 and Nano-TiO2 as Seed-Priming Agents in Enhancing Drought Tolerance of Barley Seedlings. Agronomy 2026, 16, 316. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030316

Ye X, Song R, Qi J. Physiological Mechanisms of Nano-CeO2 and Nano-TiO2 as Seed-Priming Agents in Enhancing Drought Tolerance of Barley Seedlings. Agronomy. 2026; 16(3):316. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030316

Chicago/Turabian StyleYe, Xiang, Ruijiao Song, and Juncang Qi. 2026. "Physiological Mechanisms of Nano-CeO2 and Nano-TiO2 as Seed-Priming Agents in Enhancing Drought Tolerance of Barley Seedlings" Agronomy 16, no. 3: 316. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030316

APA StyleYe, X., Song, R., & Qi, J. (2026). Physiological Mechanisms of Nano-CeO2 and Nano-TiO2 as Seed-Priming Agents in Enhancing Drought Tolerance of Barley Seedlings. Agronomy, 16(3), 316. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030316