Optimized Nitrogen Application Under Mulching Enhances Maize Yield and Water Productivity by Regulating Crop Growth and Water Use Dynamics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

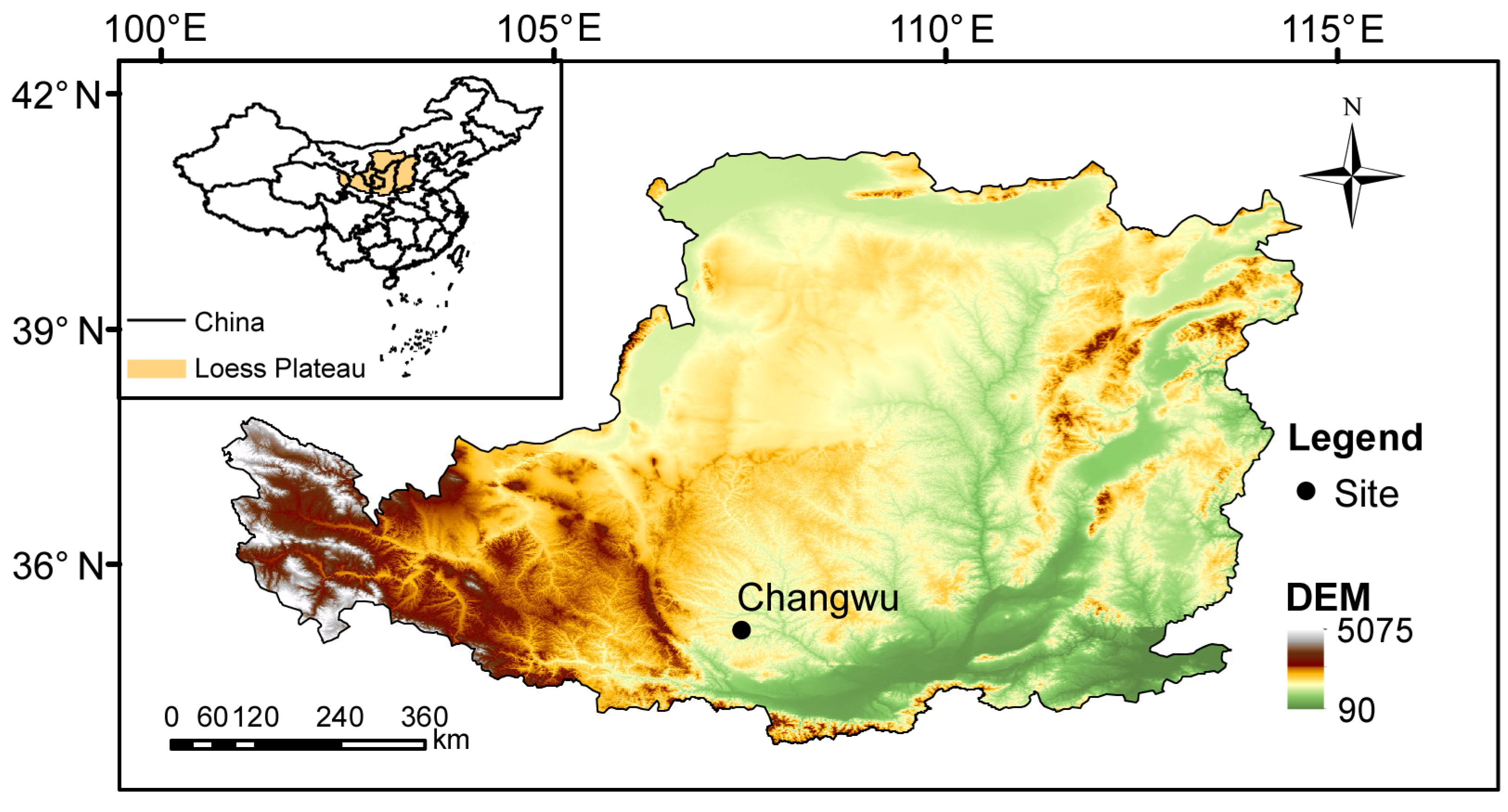

2.1. Experimental Site

2.2. Experimental Design and Treatments

2.3. Sampling and Measurements

2.4. Calculations and Analyses

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Result

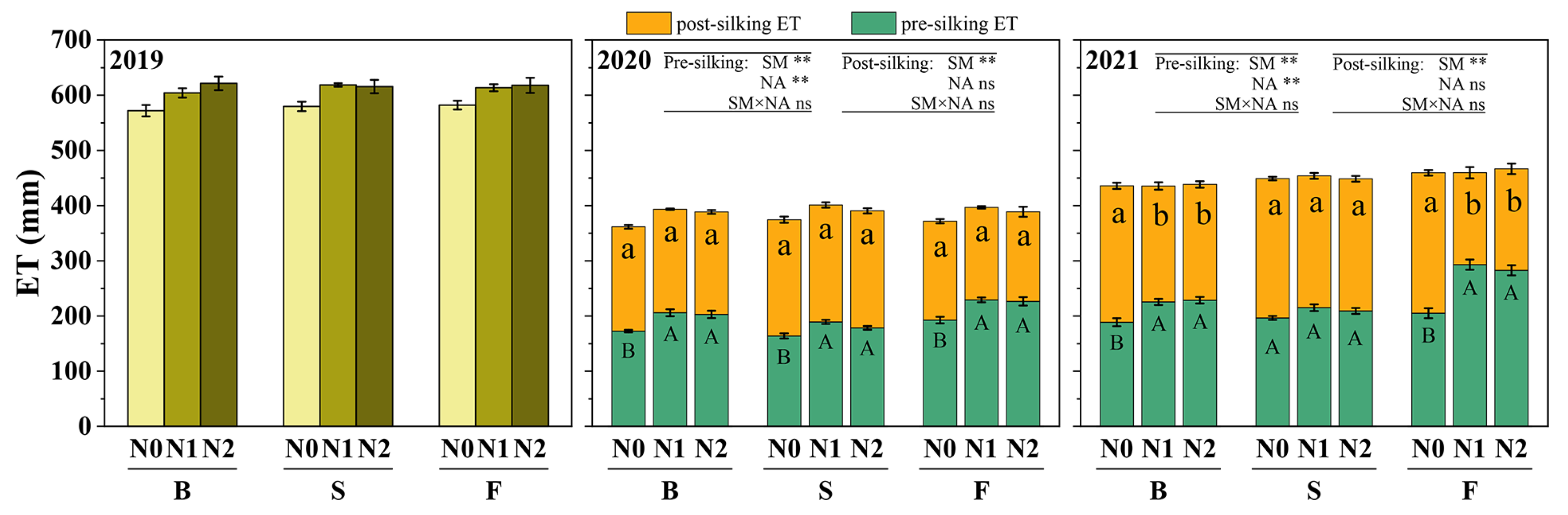

3.1. Pre- and Post-Silking ET in Spring Maize

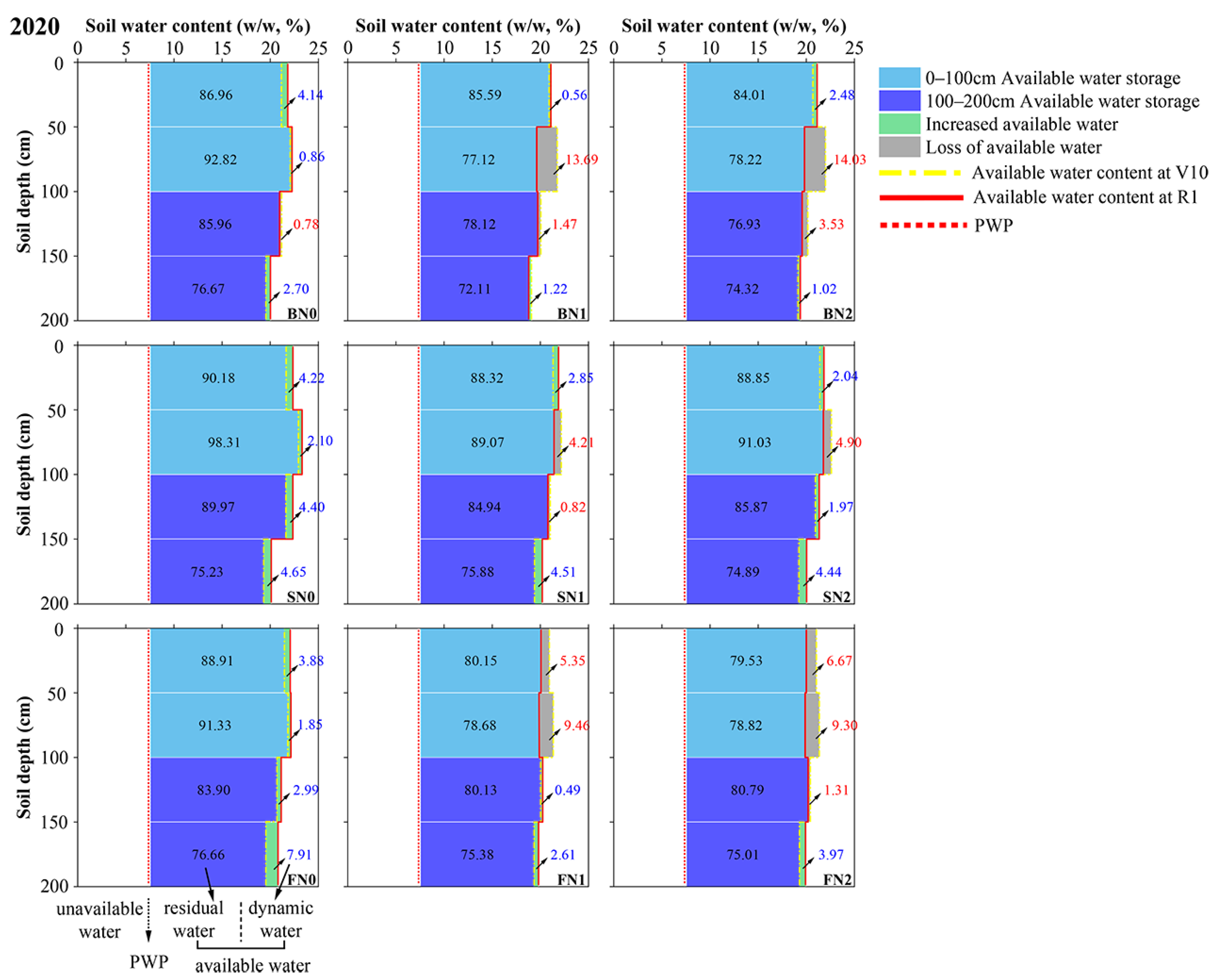

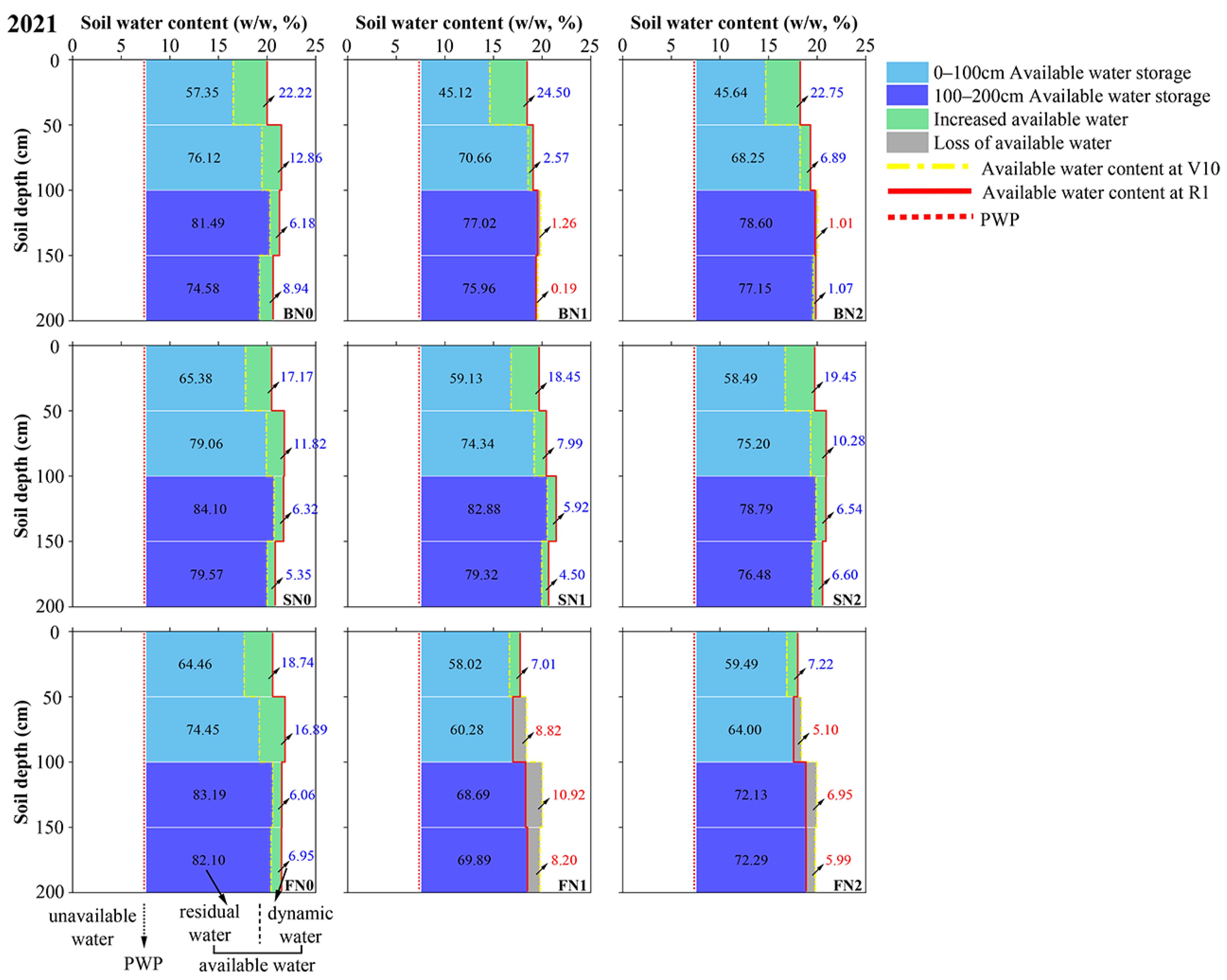

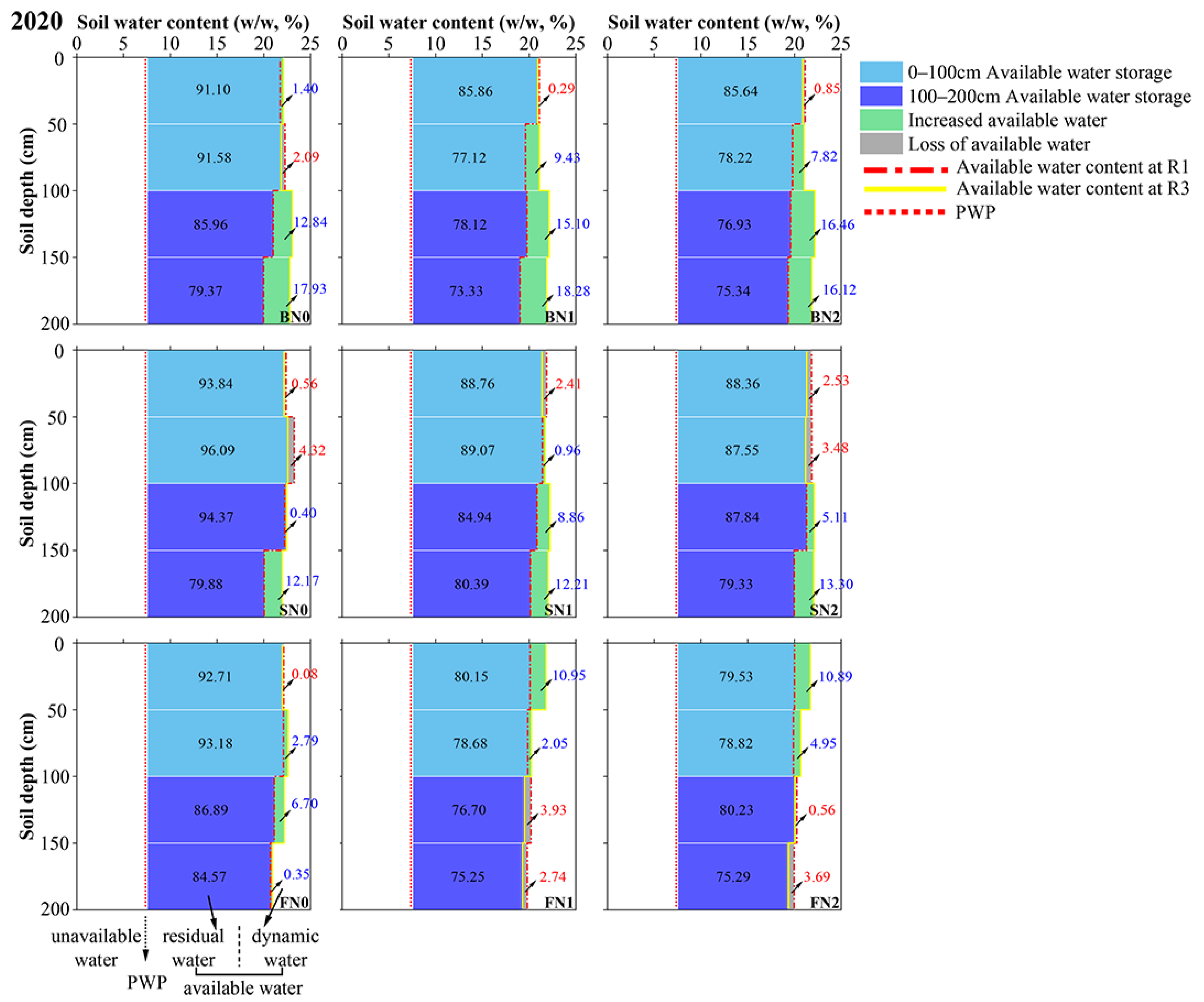

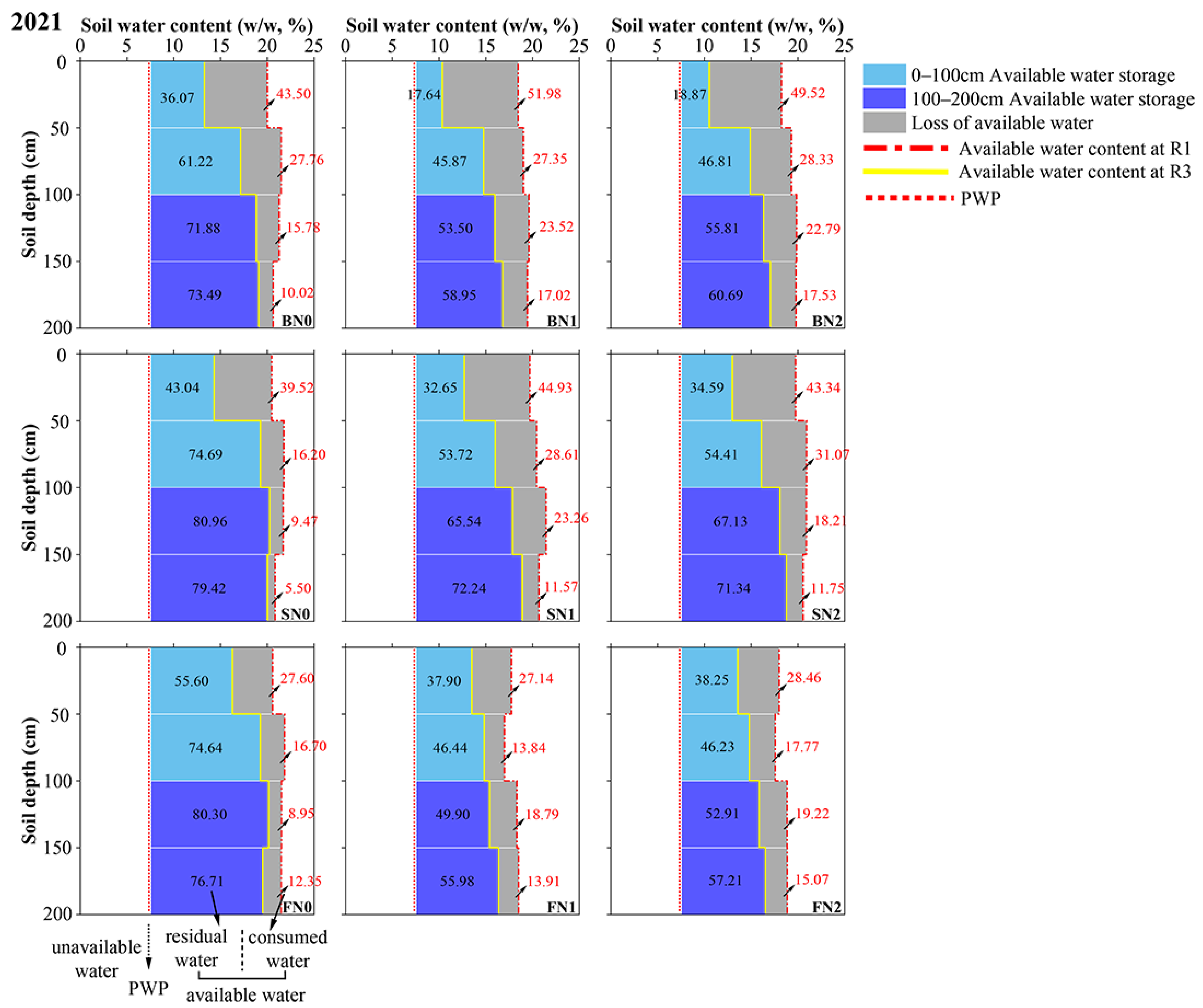

3.2. Changes in ASWS During Critical Water Demand Periods (V10–R1 and R1–R3) and SWS in R6

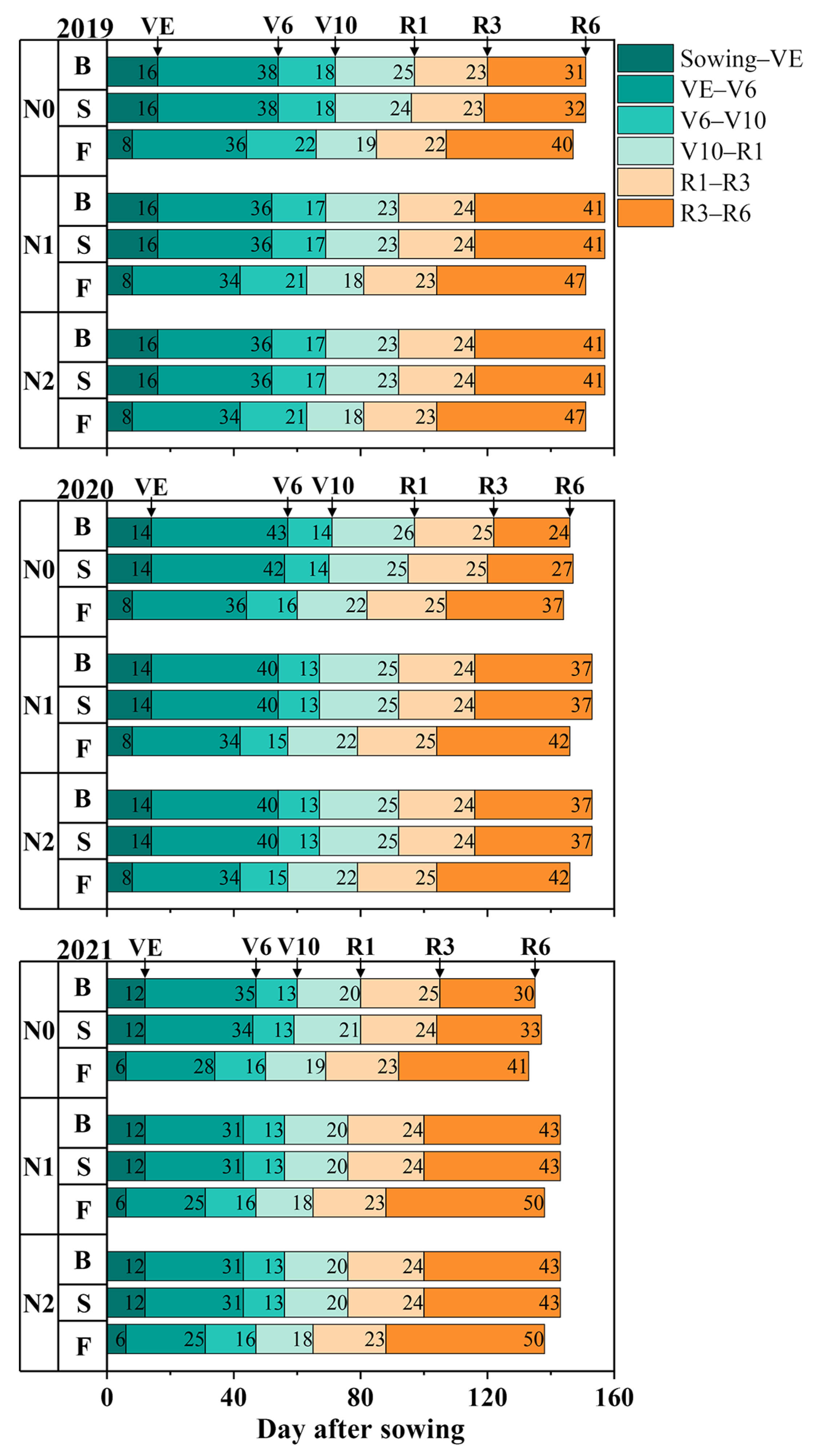

3.3. Changes in Spring Maize Phenology

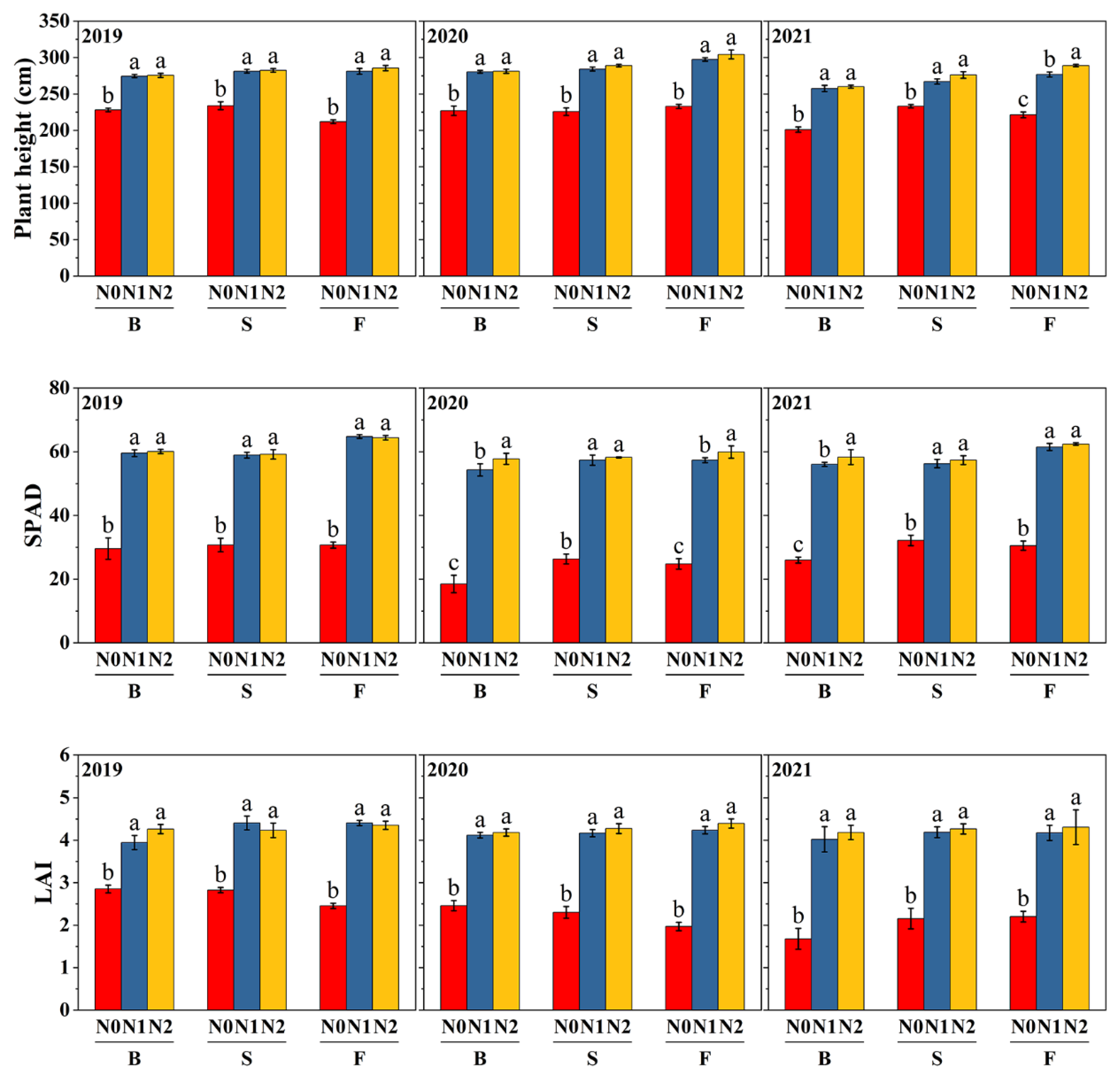

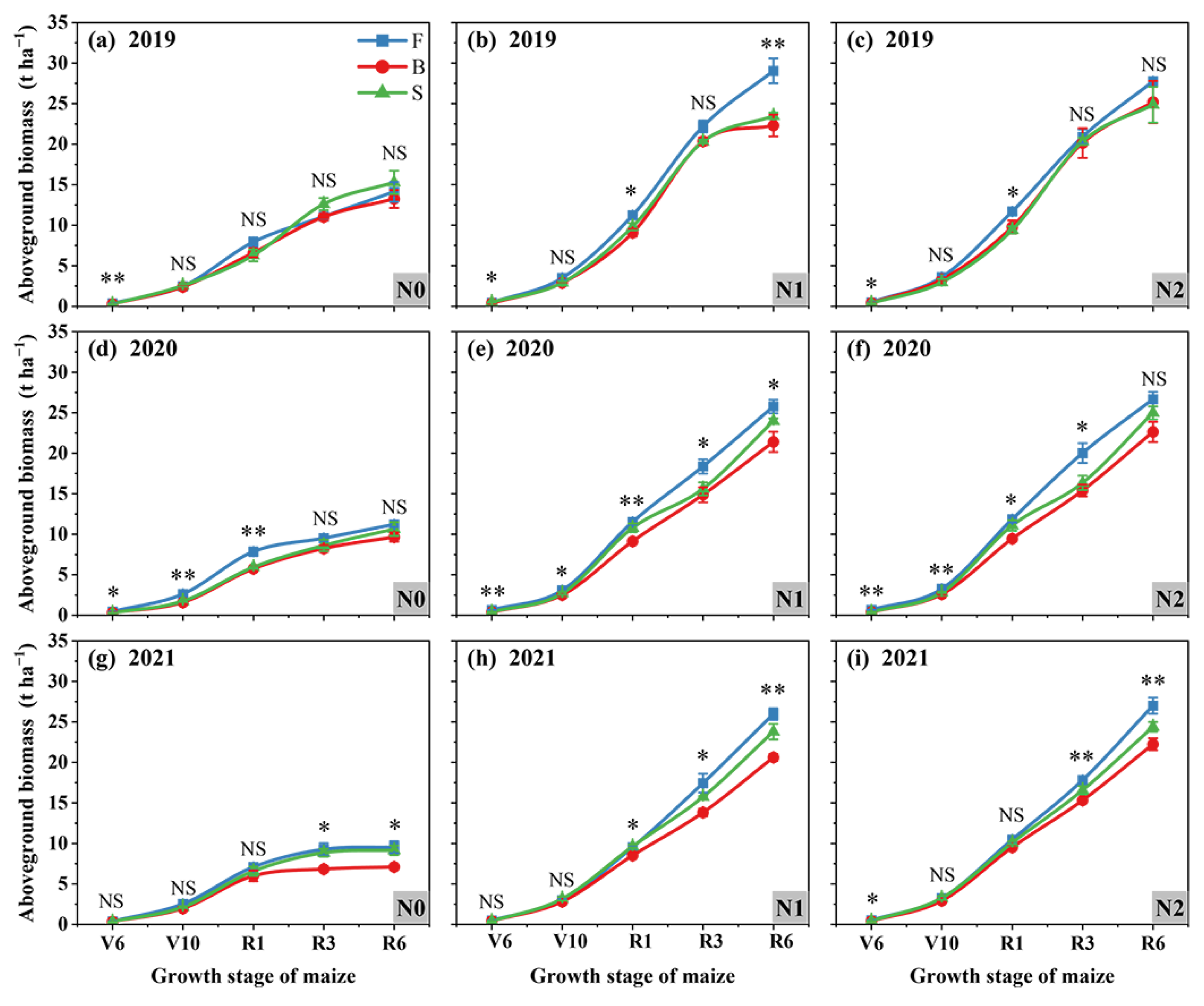

3.4. Effects of Surface Mulching and Nitrogen Application on Soil Physical Properties and Agronomic Traits of Spring Maize

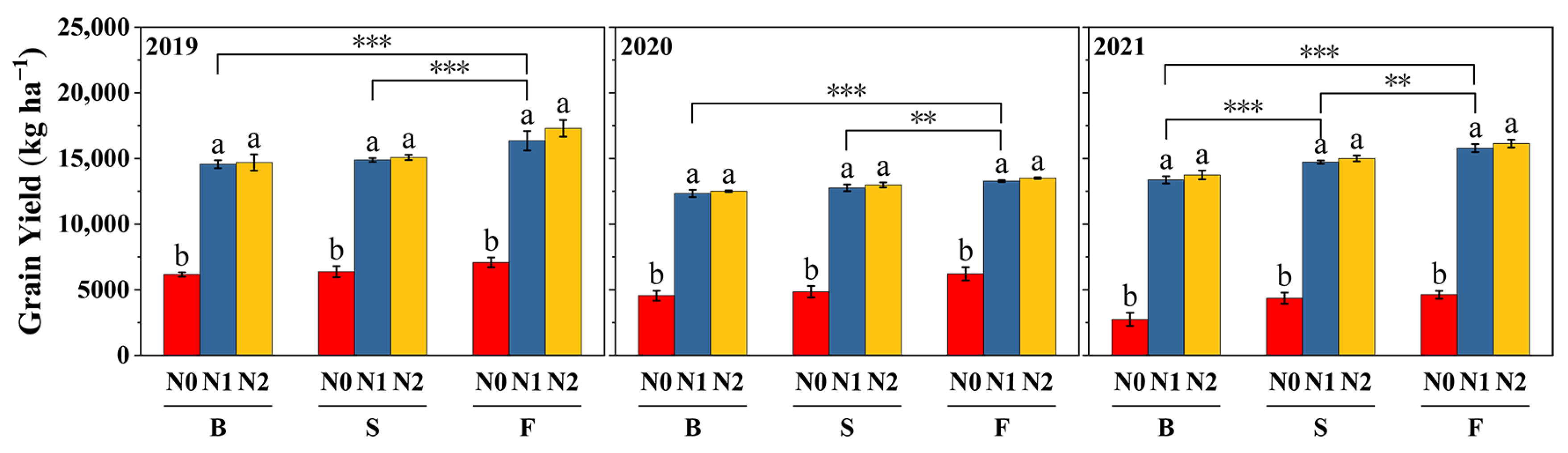

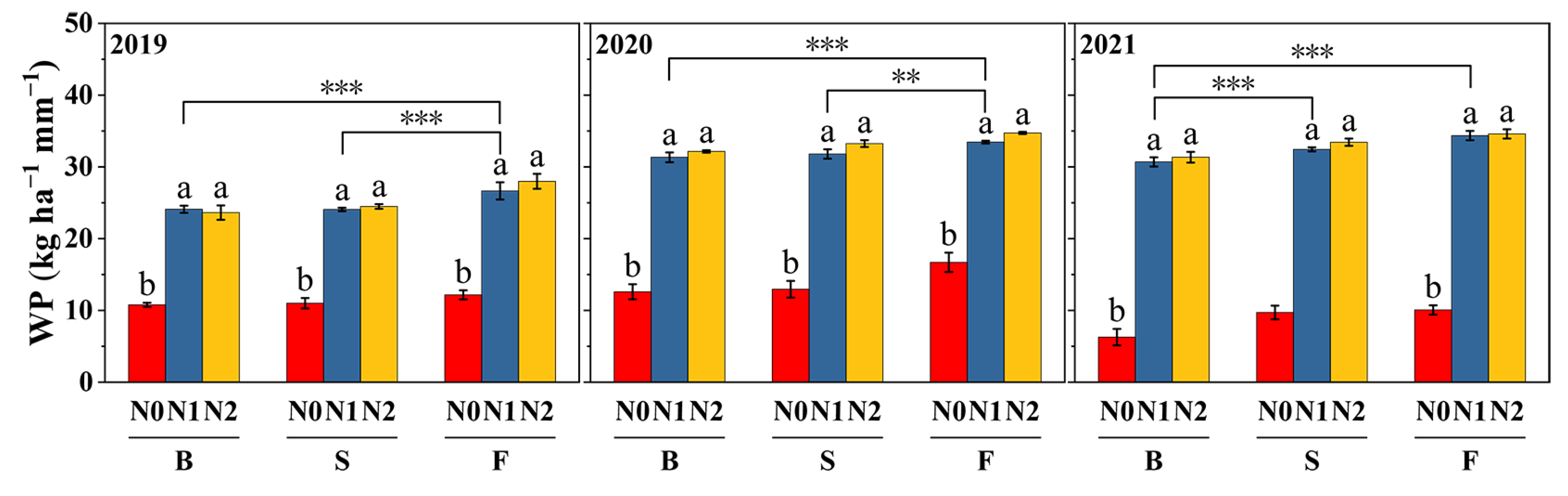

3.5. Grain Yield and WP

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Mulching and N Application on Spring Maize Phenology

4.2. Temporal and Spatial Variability in Soil Water Utilization by Spring Maize

4.3. Optimizing Survival Strategies to Improve Yield and WP

4.4. Reasonable Combination of Surface Mulching and N Application

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alharbi, S.; Felemban, A.; Abdelrahim, A.; Al-Dakhil, M. Agricultural and Technology-based strategies to improve water-use efficiency in Arid and Semiarid areas. Water 2024, 16, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.-P.; Shan, L.; Zhang, H.; Turner, N.C. Improving agricultural water use efficiency in arid and semiarid areas of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2006, 80, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Han, H.; Guo, Z.; Shuai, G.; Si, S.; Liao, S.; Xin, W.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, Z. Plastic-film-side seeding, as an alternative to traditional film mulching, improves yield stability and income in maize production in semi-arid regions. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 1021–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, F.; Wang, J.; Zhou, H.; Luo, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Li, F.; Xiong, L.; Kavagi, L.; Nguluu, S.N. Ridge-furrow plastic-mulching with balanced fertilization in rainfed maize (Zea mays L.): An adaptive management in east African Plateau. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2017, 236, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Li, L.; Effah, Z. Effects of straw mulching and reduced tillage on crop production and environment: A review. Water 2022, 14, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Beltagi, H.S.; Basit, A.; Mohamed, H.I.; Ali, I.; Ullah, S.; Kamel, E.A.; Shalaby, T.A.; Ramadan, K.M.; Alkhateeb, A.A.; Ghazzawy, H.S. Mulching as a sustainable water and soil saving practice in agriculture: A review. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, R.; Chang, X.; Yao, Y.; Qiu, Q.; Li, H.; Wei, X. Biological conservation measures are better than engineering conservation measures in improving soil quality of eroded orchards in southern China. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2022, 86, 932–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fan, J.; Xing, Y.; Xu, G.; Wang, H.; Deng, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Li, P.; Li, Z. Chapter Three—The Effects of Mulch and Nitrogen Fertilizer on the Soil Environment of Crop Plants. Adv. Agron. 2019, 153, 121–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condon, A.G.; Richards, R.; Rebetzke, G.; Farquhar, G. Improving intrinsic water-use efficiency and crop yield. Crop Sci. 2002, 42, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, Q.; Li, H. The Impact of Farmer Differentiation Trends on the Environmental Effects of Agricultural Products: A Life Cycle Assessment Approach. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Li, H.; Wang, E.; He, W.; Hao, W.; Yan, C.; Li, Y.; Mei, X.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Z.; et al. An overview of the use of plastic-film mulching in China to increase crop yield and water-use efficiency. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020, 7, 1523–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Hu, C.; Oenema, O. Soil mulching significantly enhances yields and water and nitrogen use efficiencies of maize and wheat: A meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Huang, F.; Jia, Z.; Ren, X.; Cai, T. Response of soil water, temperature, and maize (Zea may L.) production to different plastic film mulching patterns in semi-arid areas of northwest China. Soil Tillage Res. 2017, 166, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Tang, M.; Zhang, C.; Deng, M.; Li, Y.; Feng, S. Impacts of Various Straw Mulching Strategies on Soil Water, Nutrients, Thermal Regimes, and Yield in Wheat–Soybean Rotation Systems. Plants 2025, 14, 2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wang, Z.; Ma, B.; Zhang, L.; Tian, J.; He, J. Effects of Plastic Film and Gravel-Sand Mulching on Soil Moisture and Yield of Wolfberry Under Ridge-Furrow Planting in an Arid Desert Region of China’s Loess Plateau. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, F.; Wang, J.; Li, F.; Nguluu, S.N.; Ren, H.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, J.; Kariuki, C.W.; Gicheru, P.; Kavagi, L. Yield-phenology relations and water use efficiency of maize (Zea mays L.) in ridge-furrow mulching system in semiarid east African Plateau. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Li, M.; Gao, X.; Fang, F. Corn straw mulching affects Parthenium hysterophorus and rhizosphere organisms. Crop Prot. 2018, 113, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yi, S.; Ma, Y. Effects of Straw Mulching on Soil Temperature and Maize Growth in Northeast China. Teh. Vjesn. 2022, 29, 1805–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, B.; Atar, B. Effects of mulch practices on fresh ear yield and yield components of sweet corn. Turk. J. Agric. For. 2013, 37, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, F.; Xing, Z.; Guo, X.; Hui, S.; Du, L.; Ding, L. Effects of mulching with crushed wheat straw padding and plastic film on sunflower emergence, yield, and yield components under different irrigation intensity in the northwest arid regions, China. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2021, 101, 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, L.D.; Liu, J.L.; Zhu, L.; Luo, S.S.; Chen, X.P.; Li, S.Q.; Hill, R.L.; Zhao, Y. The effects of mulching on maize growth, yield and water use in a semi-arid region. Agric. Water Manag. 2013, 123, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Li, S.; Lu, J.; Penn, C.J.; Wang, Q.-W.; Lin, G.; Sardans, J.; Penuelas, J.; Wang, J.; Rillig, M.C. Consequences of 33 years of plastic film mulching and nitrogen fertilization on maize growth and soil quality. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 9174–9183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Chai, S.; Chai, Y.; Li, Y.; Lan, X.; Ma, J.; Cheng, H.; Chang, L. Mulching optimizes water consumption characteristics and improves crop water productivity on the semi-arid Loess Plateau of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 254, 106965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Quan, H.; Wu, L.; Zhang, X.; Ding, D.; Feng, H.; Siddique, K.H.; Li Liu, D.; Wang, B. Plastic mulching enhances maize yield and water productivity by improving root characteristics, green leaf area, and photosynthesis for different cultivars in dryland regions. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 305, 109105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, F.; Yang, S.; Chen, X. Soil water dynamics and water use efficiency in spring maize (Zea mays L.) fields subjected to different water management practices on the Loess Plateau, China. Agric. Water Manag. 2010, 97, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.L.; Xiong, Y.C.; Zhang, H.J.; Li, F.Q.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Y.C.; Deng, Z.R. Maize productivity and soil properties in the Loess Plateau in response to ridge-furrow cultivation with polyethylene and straw mulch. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, C.; Wu, R.; Selles, F.; Harker, K.; Clayton, G.; Bittman, S.; Zebarth, B.; Lupwayi, N. Crop yield and nitrogen concentration with controlled release urea and split applications of nitrogen as compared to non-coated urea applied at seeding. Field Crops Res. 2012, 127, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, R.M.; Roelcke, M.; Li, S.X.; Wang, X.Q.; Li, S.Q.; Stockdale, E.A.; McTaggart, I.P.; Smith, K.A.; Richter, J. The effect of fertilizer placement on nitrogen uptake and yield of wheat and maize in Chinese loess soils. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 1996, 47, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, R.H.; Middleton, A.B.; Zhang, M. Optimal time and placement of nitrogen fertilizer with direct and conventionally seeded winter wheat. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2001, 81, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassman, K.G.; Dobermann, A.; Walters, D.T. Agroecosystems, nitrogen-use efficiency, and nitrogen management. AMBIO A J. Hum. Environ. 2002, 31, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Cui, Z.; Fan, M.; Zhang, W.; Chen, X.; Jiang, R. Integrated soil–crop system management: Reducing environmental risk while increasing crop productivity and improving nutrient use efficiency in China. J. Environ. Qual. 2011, 40, 1051–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kekeli, M.A.; Wang, Q.; Rui, Y. The Role of Nano-Fertilizers in Sustainable Agriculture: Boosting Crop Yields and Enhancing Quality. Plants 2025, 14, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Zhang, F.; Chen, X.; Miao, Y.; Li, J.; Shi, L.; Xu, J.; Ye, Y.; Liu, C.; Yang, Z. On-farm evaluation of an in-season nitrogen management strategy based on soil Nmin test. Field Crops Res. 2008, 105, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Li, P.; Zheng, C.; Sun, M.; Shao, J.; Li, X.; Dong, H. Split-nitrogen application increases nitrogen-use efficiency and yield of cotton. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2023, 125, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamani, A.K.M.; Abubakar, S.A.; Si, Z.; Kama, R.; Gao, Y.; Duan, A. Suitable split nitrogen application increases grain yield and photosynthetic capacity in drip-irrigated winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under different water regimes in the North China Plain. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1105006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Luo, S.; Yue, S.; Shen, Y.; Li, S. Fate of 15 N fertilizer under different nitrogen split applications to plastic mulched maize in semiarid farmland. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2016, 105, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.M.; Xue, J.Q.; Blaylock, A.D.; Cui, Z.L.; Chen, X.P. Film-mulched maize production: Response to controlled-release urea fertilization. J. Agric. Sci. 2017, 155, 1299–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenawy, E.-R.; Hosny, A.; Saad-Allah, K. Reducing nitrogen leaching while enhancing growth, yield performance and physiological traits of rice by the application of controlled-release urea fertilizer. Paddy Water Environ. 2021, 19, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Blaylock, A.D.; Chen, X. Mixture of controlled release and normal urea to optimize nitrogen management for high-yielding (>15 Mg ha−1) maize. Field Crops Res. 2017, 204, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. FAO—UNESCO Soil Map of the World (Revised Legend, with Corrections and Updates), 1st ed.; World Soil Resources Reports 60; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- O’Kelly, B.C.; Sivakumar, V. Water Content Determinations for Peat and Other Organic Soils Using the Oven-Drying Method. Dry. Technol. 2014, 32, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Zhu, H.S.; Ren, Y.Q.; Cao, Z.R.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Z.N.; Yao, Y.F.; Zhong, Z.K.; Kong, W.B.; Qiu, Q.; et al. Erosion intensity and check dam size affect the horizontal and vertical distribution of soil particles, carbon and nitrogen: Evidence from China’s Loess Plateau. Catena 2022, 217, 106451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nleya, T.; Chungu, C.; Kleinjan, J. Corn Growth and Development. In iGrow Corn: Best Management Practices; Clay, D., Carlson, G., Clay, S., Byamukama, E., Eds.; South Dakota State University: Brookings, SD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ciampitti, I.A.; Elmore, R.W.; Lauer, J. Corn growth and development. Dent 2011, 5, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hati, K.; Mandal, K.; Misra, A.; Ghosh, P.; Bandyopadhyay, K. Effect of inorganic fertilizer and farmyard manure on soil physical properties, root distribution, and water-use efficiency of soybean in Vertisols of central India. Bioresour. Technol. 2006, 97, 2182–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, E. Editorial note on terms for crop evapotranspiration, water use efficiency and water productivity. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 289, 108548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.; Black, A. Organic carbon effects on available water capacity of three soil textural groups. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1992, 56, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.E.; Alcon, F.; Diaz-Espejo, A.; Hernandez-Santana, V.; Cuevas, M.V. Water use indicators and economic analysis for on-farm irrigation decision: A case study of a super high density olive tree orchard. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 237, 106074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Luo, X.; Wang, N.; Wu, W.; Li, Y.; Quan, H.; Zhang, T.; Ding, D.; Dong, Q.g.; Feng, H. Transparent plastic film combined with deficit irrigation improves hydrothermal status of the soil-crop system and spring maize growth in arid areas. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 265, 107536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarara, J.M. Microclimate modification with plastic mulch. Hortscience 2000, 35, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Zhou, J.X.; Zhai, X.F.; Sun, H.R.; Yue, S.C.; Guo, N.; Li, S.Q.; Shen, Y.F. Response of Maize Productivity and Resource Use Efficiency to Combined Application of Controlled-Release Urea and Normal Urea under Plastic Film Mulching in Semiarid Farmland. Agron. J. 2019, 111, 3194–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Li, X.; Šimůnek, J.; Shi, H.; Ding, Z.; Zhang, Y. The effects of biodegradable and plastic film mulching on nitrogen uptake, distribution, and leaching in a drip-irrigated sandy field. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 292, 106817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xie, Y.; Jiang, H.; Wu, B.; Niu, J. Soil water status and root distribution across the rooting zone in maize with plastic film mulching. Field Crops Res. 2014, 156, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrizzi, K.; Garcıa, F.; Costa, J.; Picone, L. Soil water dynamics, physical properties and corn and wheat responses to minimum and no-tillage systems in the southern Pampas of Argentina. Soil Tillage Res. 2005, 81, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Hafeez, M.B.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, Q.; Wang, R.; Wang, X.; Li, J. No-tillage and subsoiling increased maize yields and soil water storage under varied rainfall distribution: A 9-year site-specific study in a semi-arid environment. Field Crops Res. 2020, 255, 107867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, M.; Meng, Z.; Liu, K.; Sui, N. Nitrogen increases drought tolerance in maize seedlings. Funct. Plant Biol. 2019, 46, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Cao, H.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Hu, Q.; Xue, W. By increasing infiltration and reducing evaporation, mulching can improve the soil water environment and apple yield of orchards in semiarid areas. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 253, 106936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Shi, H.; Jia, Y.; Miao, Q.; Jia, Q.; Wang, N. Infiltration and water use efficiency of maize fields with drip irrigation and biodegradable mulches in the west liaohe plain, China. Plants 2023, 12, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhai, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Jiang, R.; Hill, R.L.; Si, B.; Hao, F. Simulation of soil water and heat flow in ridge cultivation with plastic film mulching system on the Chinese Loess Plateau. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 202, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, L.; Xue, X.; Kamran, M.; Ahmad, I.; Dong, Z.; Liu, T.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, P.; Han, Q. Plastic film mulching stimulates soil wet-dry alternation and stomatal behavior to improve maize yield and resource use efficiency in a semi-arid region. Field Crops Res. 2019, 233, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Pei, D.; Sun, H.Y.; Chen, S.L. Effects of straw mulching on soil temperature, evaporation and yield of winter wheat: Field experiments on the North China Plain. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2007, 150, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comas, L.H.; Bauerle, T.; Eissenstat, D. Biological and environmental factors controlling root dynamics and function: Effects of root ageing and soil moisture. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2010, 16, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Chen, G.; Hu, Y.; Wu, S.; Feng, H. Alternating wide ridges and narrow furrows with film mulching improves soil hydrothermal conditions and maize water use efficiency in dry sub-humid regions. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 245, 106559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Xu, H. Productivity and soil response to plastic film mulching durations for spring wheat on entisols in the semiarid Loess Plateau of China. Soil Tillage Res. 2004, 78, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Lei, T.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, P.; Han, Y.; Hu, C.; Yang, X.; Sadras, V.; Zhang, S. Responses of yield and water use efficiency to the interaction between water supply and plastic film mulch in winter wheat-summer fallow system. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 266, 107545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fan, J.; Fu, W.; Du, M.; Zhou, G.; Zhou, M.; Hao, M. Good harvests of winter wheat from stored soil water and improved temperature during fallow period by plastic film mulching. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 274, 107910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, P.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Wang, R. No-tillage with straw mulching improved grain yield by reducing soil water evaporation in the fallow period: A 12-year study on the Loess Plateau. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 224, 105504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Cai, H.; Fang, H.; Chen, P.; Li, Y.; Li, Y. Soil hydro-thermal characteristics, maize yield and water use efficiency as affected by different biodegradable film mulching patterns in a rain-fed semi-arid area of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 245, 106560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Shi, Z.; Pan, W.; Liao, Y.; Li, T.; Qin, X. Response of root traits to plastic film mulch and its effects on yield. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 209, 104930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Li, Y.; Gu, X.; Yu, M.; Du, Y.; Chen, P.; Li, Y. Evapotranspiration partitioning, water use efficiency, and maize yield under different film mulching and nitrogen application in northwest China. Field Crops Res. 2021, 264, 108103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Li, S.; Gao, Y.; Tian, X. Effect of plastic sheet mulch, wheat straw mulch, and maize growth on water loss by evaporation in dryland areas of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2013, 116, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresović, B.; Tapanarova, A.; Tomić, Z.; Životić, L.; Vujović, D.; Sredojević, Z.; Gajić, B. Grain yield and water use efficiency of maize as influenced by different irrigation regimes through sprinkler irrigation under temperate climate. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 169, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mairata, A.; Labarga, D.; Puelles, M.; Rivacoba, L.; Portu, J.; Pou, A. Organic Mulching Versus Soil Conventional Practices in Vineyards: A Comprehensive Study on Plant Physiology, Agronomic, and Grape Quality Effects. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.B.; Zhang, W.T.; Li, S.J.; Wang, J.; Liu, G.B.; Xu, M.X. Severe depletion of available deep soil water induced by revegetation on the arid and semiarid Loess Plateau. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 491, 119156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Fang, J.; Huang, J.; Lei, D.; Xing, Z. The Differences in Water Consumption Between Pinus and Salix in the Mu Us Sandy Land, a Semiarid Region of Northwestern China. Water 2025, 17, 2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powlson, D.S.; Gregory, P.J.; Whalley, W.R.; Quinton, J.N.; Hopkins, D.W.; Whitmore, A.P.; Hirsch, P.R.; Goulding, K.W. Soil management in relation to sustainable agriculture and ecosystem services. Food Policy 2011, 36, S72–S87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Qin, A.; Gao, Y.; Ma, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, B.; Ning, D.; Zhang, K.; Gong, W.; Sun, M. Effects of water deficit at different stages on growth and ear quality of waxy maize. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1069551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Yan, W.M.; Zhang, Y.W.; Shangguan, Z.P. Severe depletion of soil moisture following land-use changes for ecological restoration: Evidence from northern China. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 366, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampitti, I.A.; Vyn, T.J. Physiological perspectives of changes over time in maize yield dependency on nitrogen uptake and associated nitrogen efficiencies: A review. Field Crops Res. 2012, 133, 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Luo, S.; Li, X.; Yue, S.; Shen, Y.; Li, S. Effect of split application of nitrogen on nitrous oxide emissions from plastic mulching maize in the semiarid Loess Plateau. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 220, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindasamy, P.; Muthusamy, S.K.; Bagavathiannan, M.; Mowrer, J.; Jagannadham, P.T.K.; Maity, A.; Halli, H.M.; GK, S.; Vadivel, R.; TK, D. Nitrogen use efficiency—A key to enhance crop productivity under a changing climate. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1121073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhao, D.; Liu, S.; Liao, Y.; Han, J. Can controlled-release urea replace the split application of normal urea in China? A meta-analysis based on crop grain yield and nitrogen use efficiency. Field Crops Res. 2022, 275, 108343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment Code | Mulching | N Application |

|---|---|---|

| BN0 | No mulching | No application |

| BN1 | No mulching | Split application of urea |

| BN2 | No mulching | Controlled-release urea + urea (1:2) |

| SN0 | Straw mulching | No application |

| SN1 | Straw mulching | Split application of urea |

| SN2 | Straw mulching | Controlled-release urea + urea (1:2) |

| FN0 | Plastic film mulching | No application |

| FN1 | Plastic film mulching | Split application of urea |

| FN2 | Plastic film mulching | Controlled-release urea + urea (1:2) |

| Growth | Precipitation (mm) | Average Temperature (°C) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stages | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| Sowing–VE | 68.4 | 35.2 | 27.4 | 12.73 | 16.81 | 16.26 |

| VE–V6 | 70.8 | 21.4 | 48.4 | 16.92 | 18.02 | 18.86 |

| V6–V10 | 74.2 | 97.2 | 14.2 | 18.94 | 20.24 | 21.66 |

| V10–R1 | 186.8 | 83.4 | 84.8 | 21.82 | 20.13 | 22.60 |

| R1–R3 | 79.9 | 128.8 | 11 | 23.37 | 20.83 | 22.91 |

| R3–R6 | 202.9 | 47.8 | 275.2 | 16.90 | 16.79 | 17.92 |

| Growing Season | 683 | 413.8 | 461 | 15.50 | 17.69 | 18.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sun, H.; Wang, X.; Duan, S.; Cui, M.; Xing, G.; Yue, S.; Xu, M.; Shen, Y. Optimized Nitrogen Application Under Mulching Enhances Maize Yield and Water Productivity by Regulating Crop Growth and Water Use Dynamics. Agronomy 2026, 16, 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030290

Sun H, Wang X, Duan S, Cui M, Xing G, Yue S, Xu M, Shen Y. Optimized Nitrogen Application Under Mulching Enhances Maize Yield and Water Productivity by Regulating Crop Growth and Water Use Dynamics. Agronomy. 2026; 16(3):290. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030290

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Haoran, Xufeng Wang, Shengdan Duan, Mengni Cui, Guangyao Xing, Shanchao Yue, Miaoping Xu, and Yufang Shen. 2026. "Optimized Nitrogen Application Under Mulching Enhances Maize Yield and Water Productivity by Regulating Crop Growth and Water Use Dynamics" Agronomy 16, no. 3: 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030290

APA StyleSun, H., Wang, X., Duan, S., Cui, M., Xing, G., Yue, S., Xu, M., & Shen, Y. (2026). Optimized Nitrogen Application Under Mulching Enhances Maize Yield and Water Productivity by Regulating Crop Growth and Water Use Dynamics. Agronomy, 16(3), 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030290