Leaf Removal Enhances Tuber Yield in Jerusalem Artichoke by Modulating Rhizosphere Nutrient Availability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Experimental Site

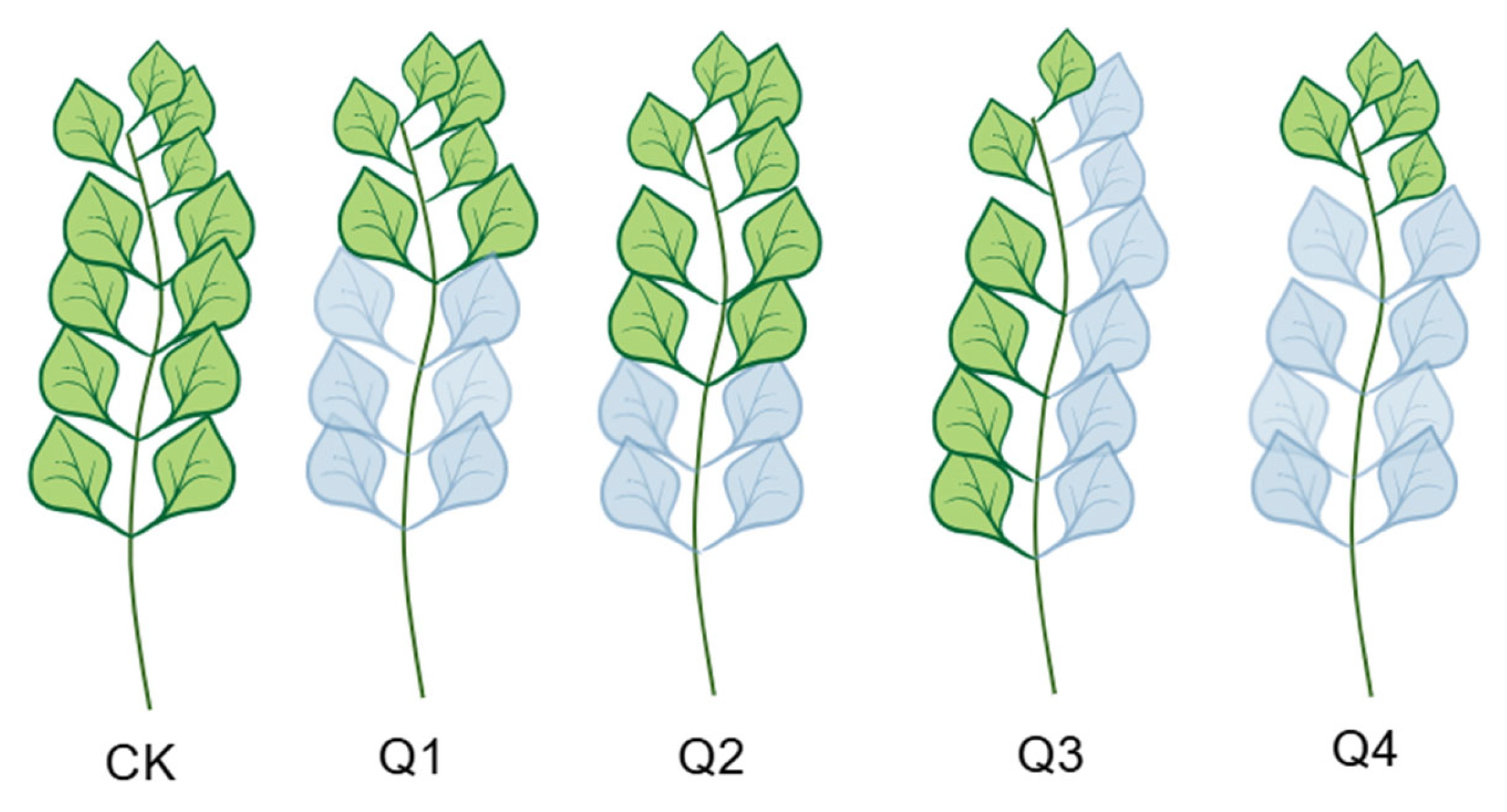

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Measured Parameters and Methods

2.3.1. Tuber Yield Measurement

2.3.2. Soil Sampling

2.3.3. Soil Nutrient Analysis

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

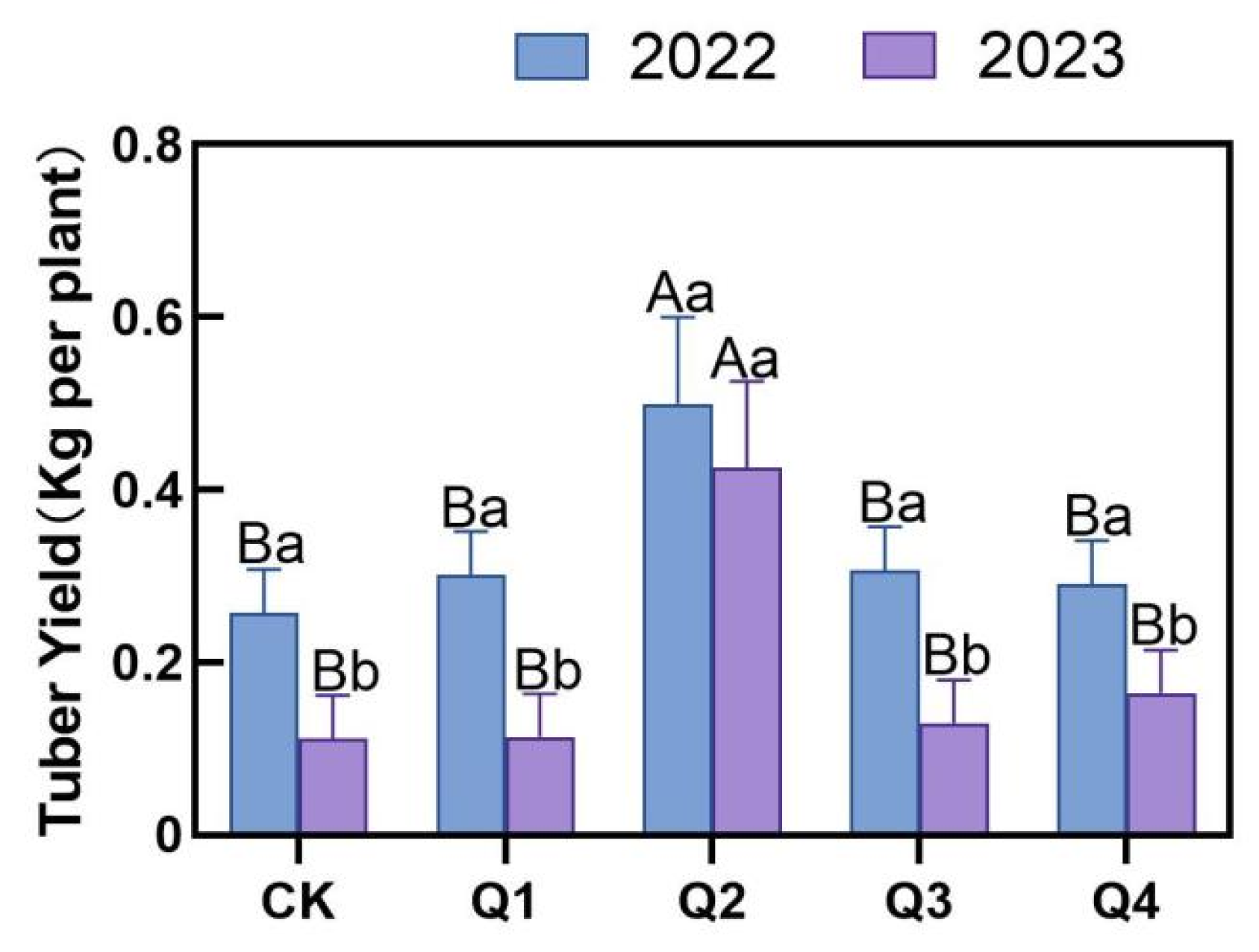

3.1. Effects of Leaf Removal on Tuber Yield of Jerusalem Artichoke

3.2. Effects of Leaf Removal on Soil Available Nutrient Content

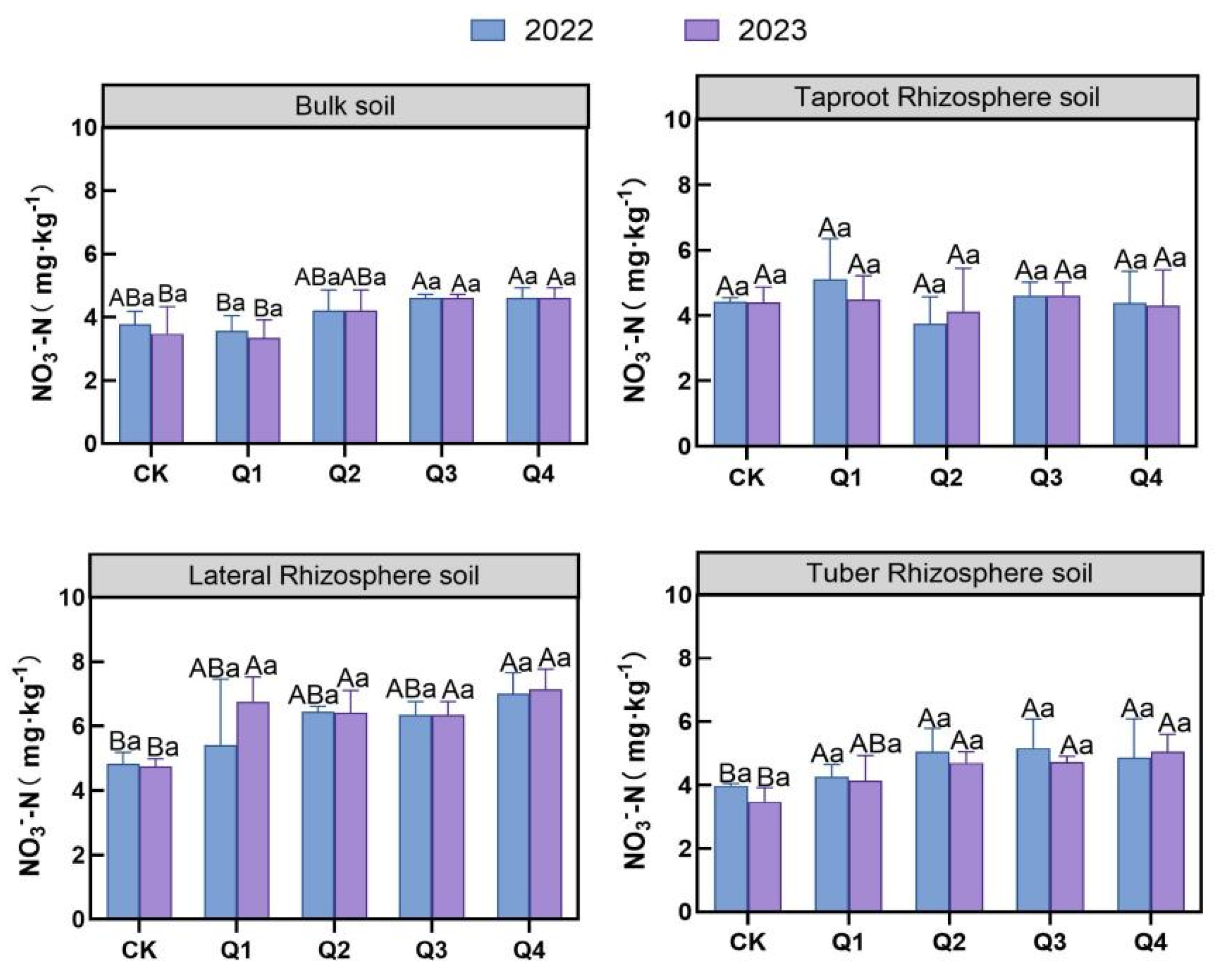

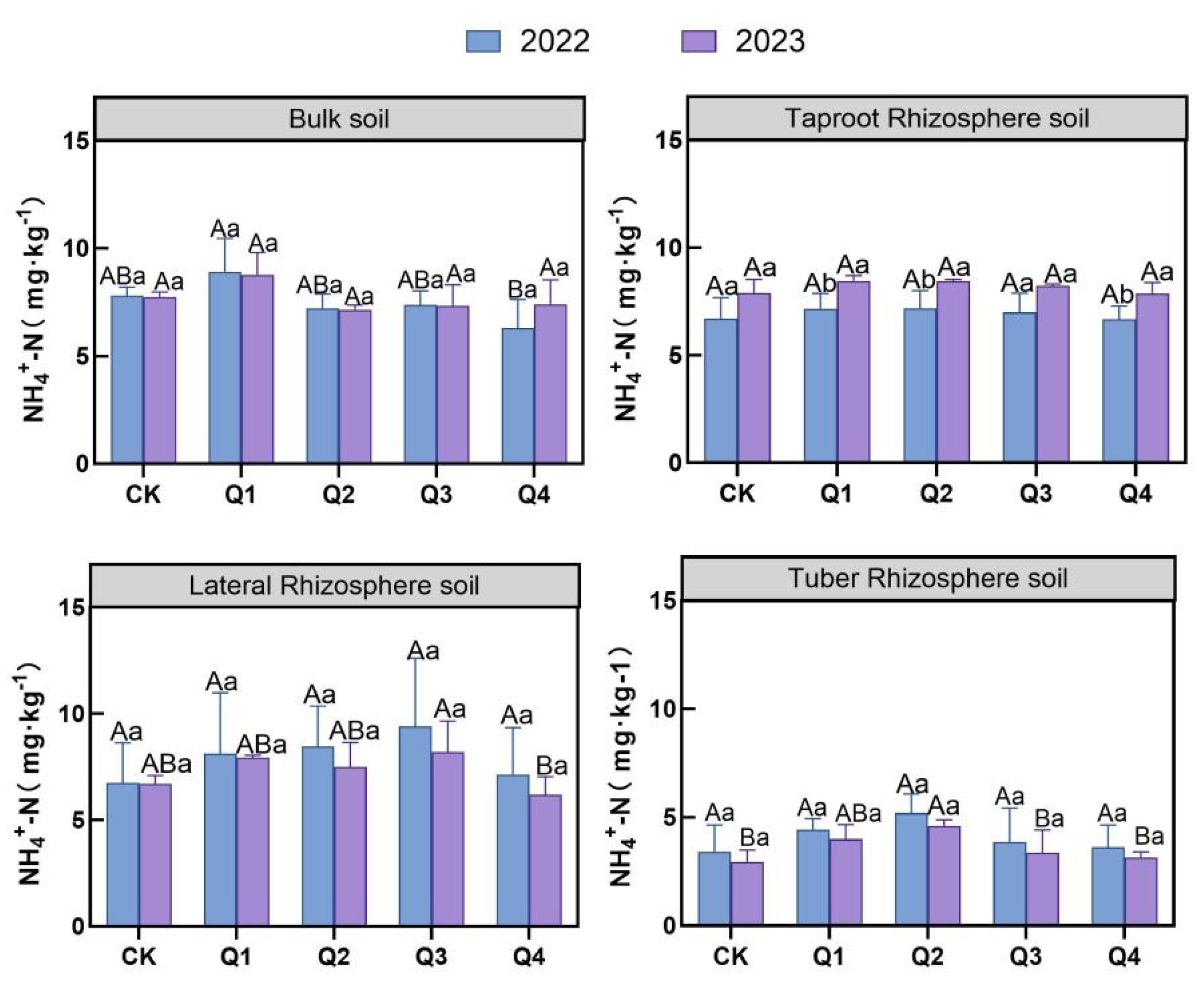

3.2.1. Effects of Leaf Removal on Soil Nitrate and NH4+-N

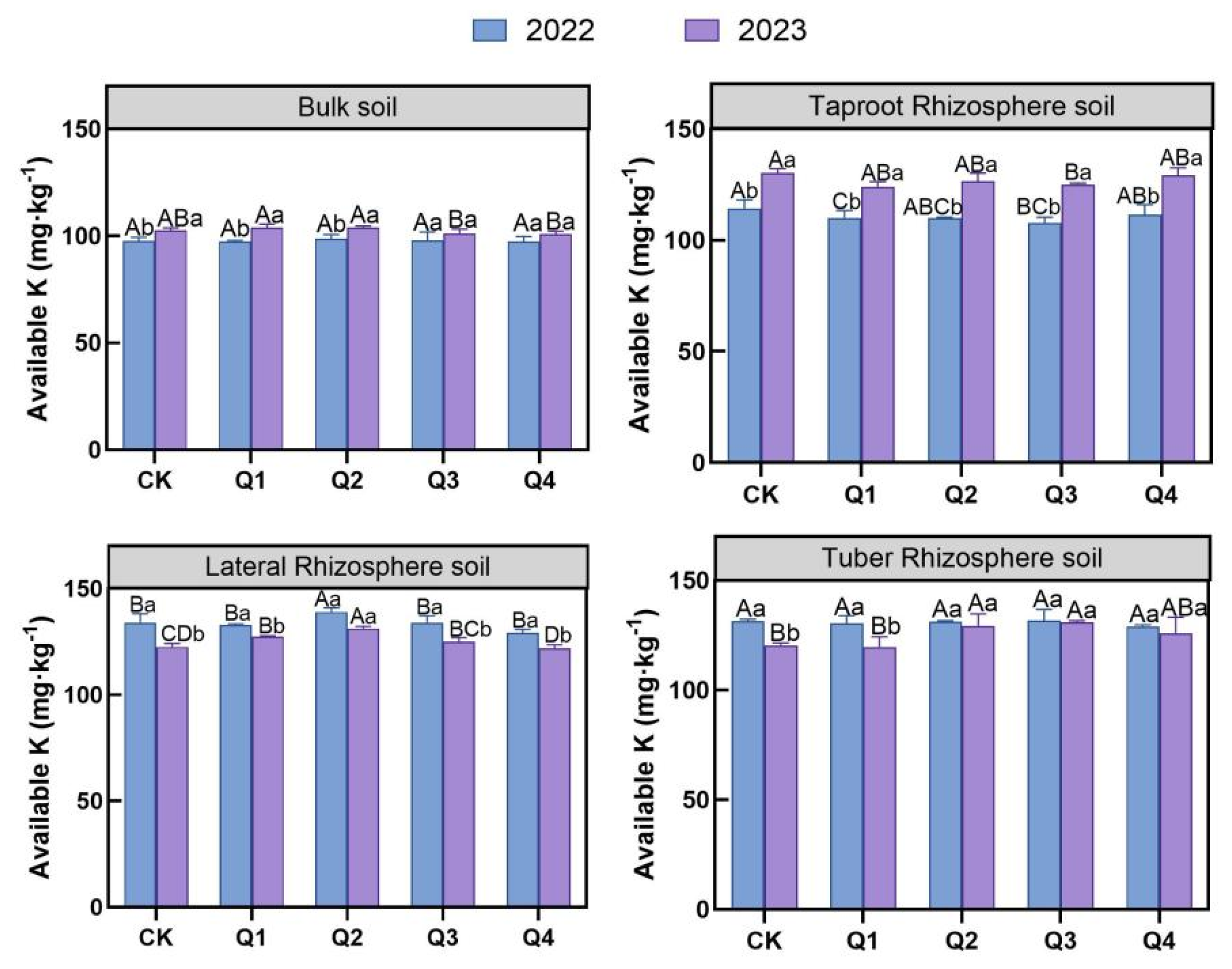

3.2.2. Effects of Leaf Removal on Soil Available Potassium

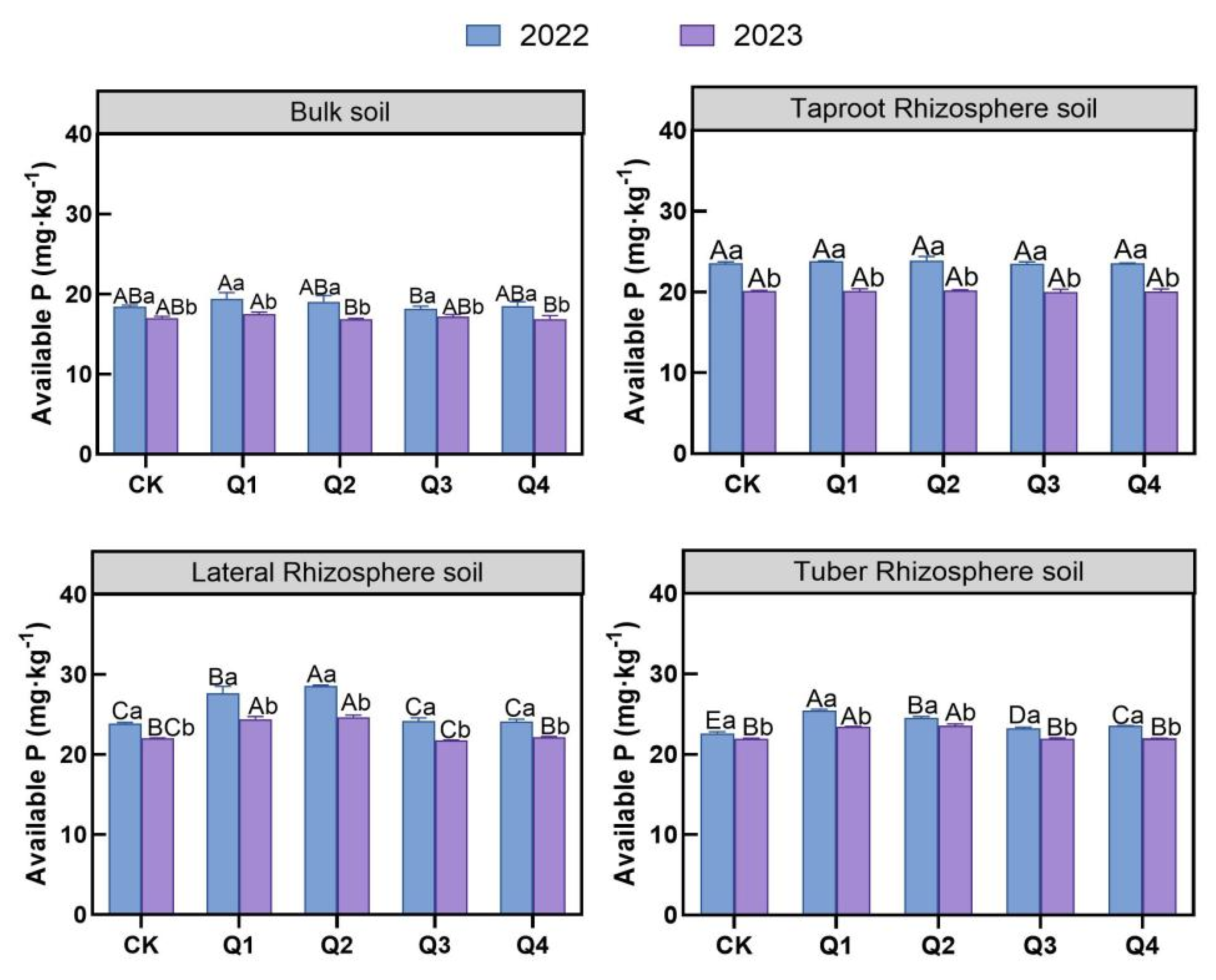

3.2.3. Effects of Leaf Removal on Soil Available Phosphorus

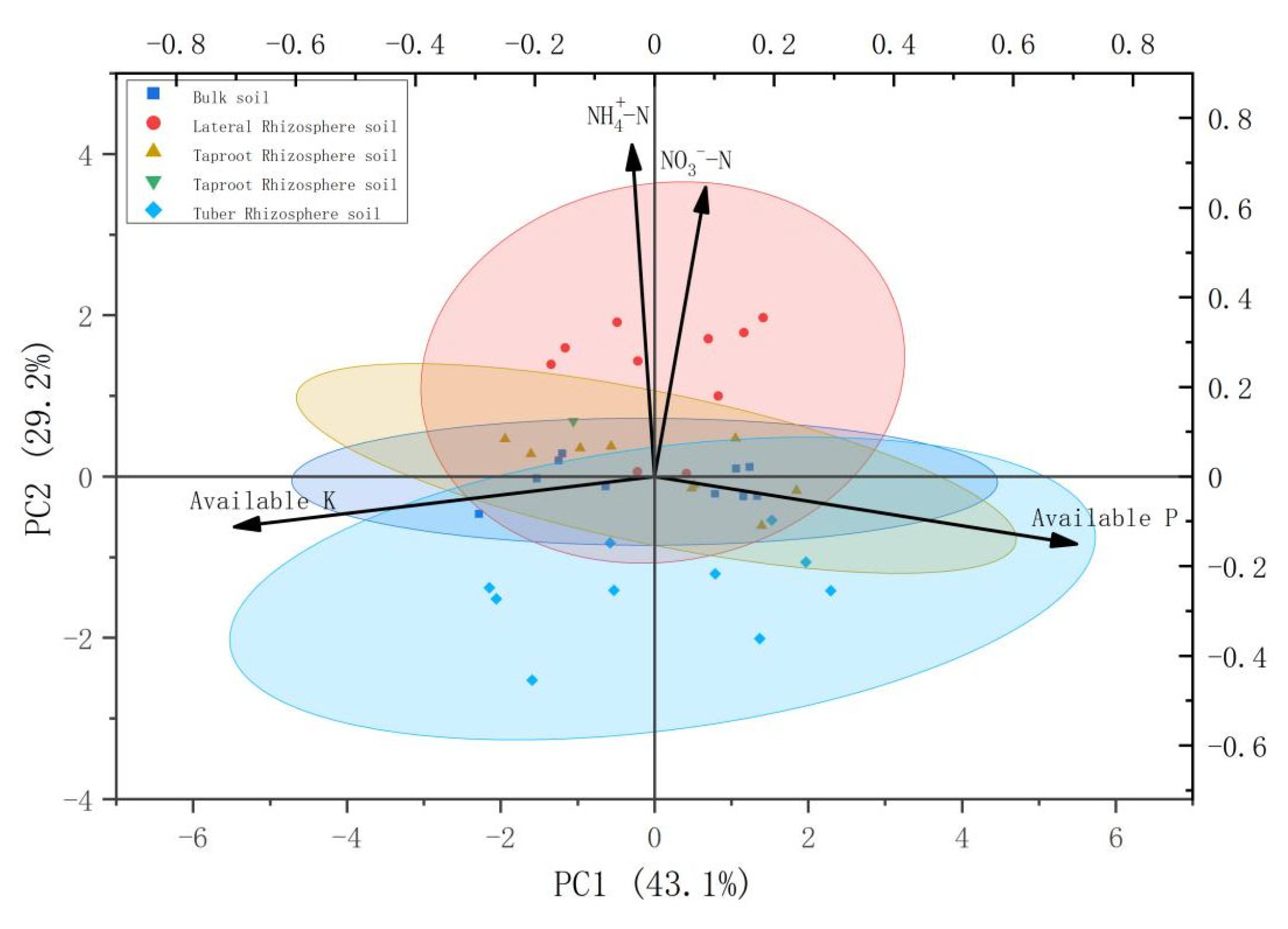

3.3. PCA

3.4. Correlation Analysis

3.5. Interaction Between Year and Leaf Removal Treatments

4. Discussion

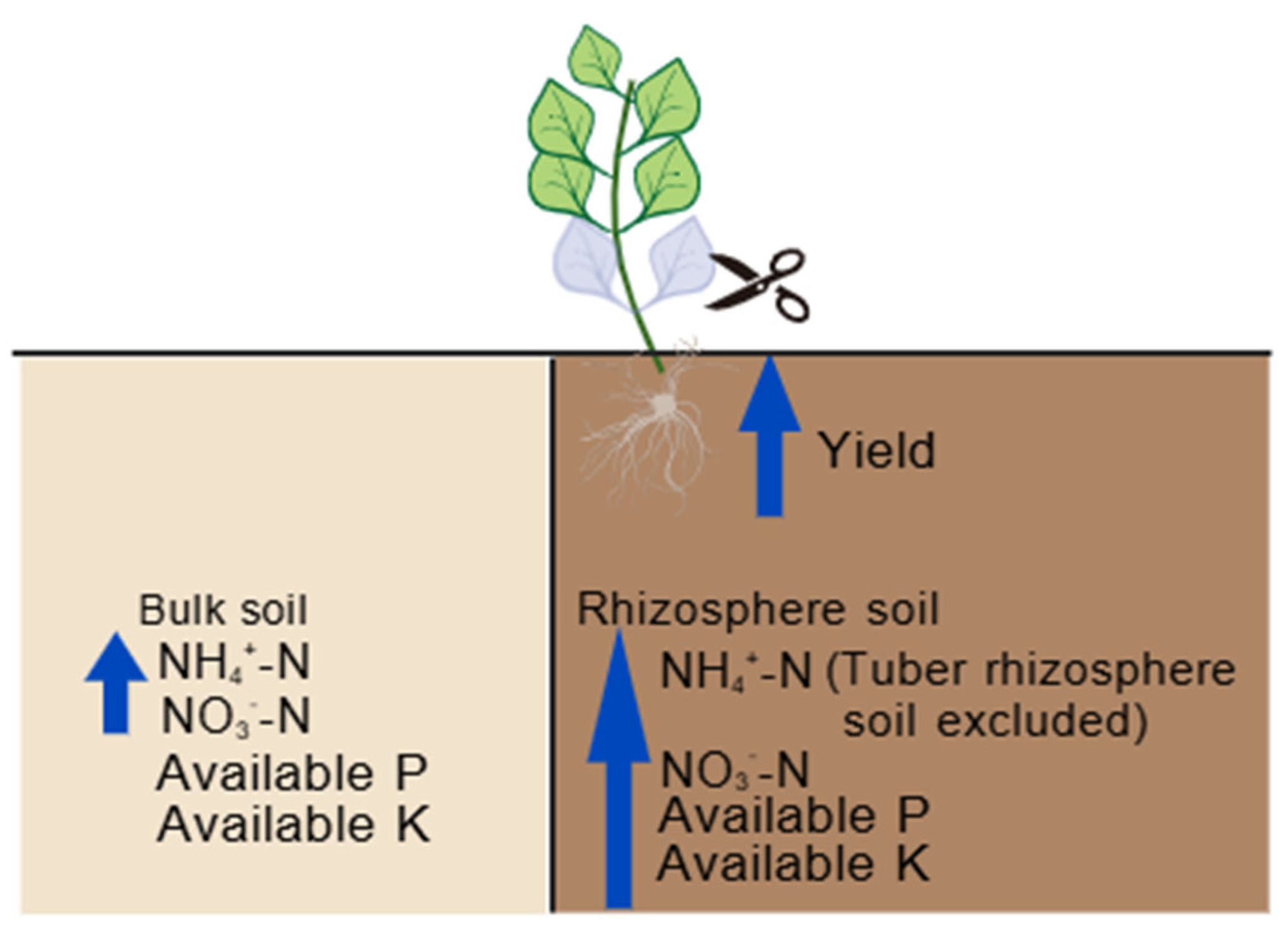

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CK | Control (no leaf removal) |

| Q1 | Lower half leaf removal treatment |

| Q2 | Lower one-third leaf removal treatment |

| Q3 | Lateral branch leaf removal treatment |

| Q4 | Opposite leaf removal treatment |

| NO3−-N | Nitrate nitrogen |

| NH4+-N | Ammonium nitrogen |

| AK | Available potassium |

| AP | Available phosphorus |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PC1 | First principal component |

| PC2 | Second principal component |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| HSD | Honestly significant difference |

References

- Jiang, Z.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, C.; Zhu, H.; Zhai, H.; He, S.; Gao, S.; Zhao, N.; Zhang, H.; et al. Source-sink synergy is the key unlocking sweet potato starch yield potential. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, W.; Jiang, Z.; Lin, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Mo, Z. Optimized carbon–nitrogen fertilization boosts fragrant rice (Oryza sativa L.) yield and quality via enhanced photosynthesis, antioxidant defense, and osmoregulation. Plants 2025, 14, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- South, P.F.; Cavanagh, A.P.; Liu, H.W.; Ort, D.R. Synthetic glycolate metabolism pathways stimulate crop growth and productivity in the field. Science 2019, 363, eaat9077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosado-Souza, L.; Yokoyama, R.; Sonnewald, U.; Fernie, A.R. Understanding source-sink interactions: Progress in model plants and translational research to crops. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 96–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, G.; Guzmán-Delgado, P.; Santos, E.; Adaskaveg, J.A.; Blanco-Ulate, B.; Ferguson, L.; Zwieniecki, M.A.; Fernández-Suela, E. Interactive effect of branch source-sink ratio and leaf aging on photosynthesis in pistachio. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1194177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, S.R.; Chrobok, D.; Juvany, M.; Delhomme, N.; Lindén, P.; Brouwer, B.; Ahad, A.; Moritz, T.; Jansson, S.; Gardeström, P.; et al. Darkened leaves use different metabolic strategies for senescence and survival. Plant Physiol. 2018, 177, 132–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ershadimanesh, K.; Siosemardeh, A.; Hoseeinpanahi, F. Evaluation of source-sink manipulation through defoliation treatments in promising bread wheat lines under optimal irrigation and rainfed conditions. Front. Agron. 2024, 6, 1393267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intrieri, C.; Filippetti, I.; Allegro, G.; Valentini, G.; Pastore, C.; Colucci, E. The effectiveness of basal shoot mechanical leaf removal at the onset of bloom to control crop on cv. Sangiovese (Vitis vinifera L.): Report on a three-year trial. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2016, 37, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Raza, M.A.; van der Werf, W.; Ahmed, M.; Yang, W. Removing top leaves increases yield and nutrient uptake in maize plants. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2020, 118, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liava, V.; Karkanis, A.; Danalatos, N.; Tsiropoulos, N. Cultivation practices, adaptability and phytochemical composition of Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus L.): A weed with economic value. Agronomy 2021, 11, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignon, C.P.; Jaiswal, D.; McGrath, J.M.; Long, S.P. Loss of photosynthetic efficiency in the shade: An Achilles heel for the dense modern stands of our most productive C4 crops? J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Qian, H.; Huang, R.; He, W.; Jiang, H.; Shen, A.; Li, Z.; Hu, Y. Rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere soil microbial communities in alpine desertified grassland affected by vegetation restoration. Plants 2025, 14, 1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Standard Operating Procedure for Soil Available Phosphorus—Olsen Method; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, M.L. Soil Chemical Analysis; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Fayose, T.; Thomas, E.; Radu, T.; Dillingham, P.; Ullah, S.; Radu, A. Concurrent measurement of nitrate and ammonium in water and soil samples using ion-selective electrodes: Tackling sensitivity and precision issues. Anal. Sci. Adv. 2021, 2, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, S.; Kong, L. Source-sink modifications affect leaf senescence and grain mass in wheat as revealed by proteomic analysis. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Sun, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, Q.; Li, H. Photosynthesis product allocation and yield in sweet potato in response to different late-season irrigation levels. Plants 2023, 12, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Tang, S.; Dengzeng, Z.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, T.; Ma, X. Root exudates contribute to belowground ecosystem hotspots: A review. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 937940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrar, J.; Hawes, M.; Jones, D.; Lindow, S. How Roots Control the Flux of Carbon to the Rhizosphere. Ecology 2003, 84, 827–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; He, F.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Xiao, H.; Hoang, D.T.T.; Pu, S.; Razavi, B.S. Nutrients in the rhizosphere: A meta-analysis of content, availability, and influencing factors. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 826, 153908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Zhang, F.; Xie, X.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, X. Effects of N and P addition on nutrient content and stoichiometry of rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere soils of alfalfa in alkaline soil. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.K.; Sutradhar, A.K.; Duke, S.E.; Lehman, R.M.; Schumacher, T.E.; Lobb, D.A. Key soil properties and their relationships with crop yields as affected by soil-landscape rehabilitation. Agron. J. 2023, 115, 2404–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruwanto, B.H.; Cheng, W.; Tawaraya, K. First-order lateral roots drive the highest rhizosphere acid phosphatase activity in soybean under phosphorus deficiency. Rhizosphere 2025, 36, 101166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, J.M.; da Silva, T.F.; Vollu, R.E.; Blank, A.F.; Ding, G.-C.; Seldin, L.; Smalla, K. Plant age and genotype affect the bacterial community composition in the tuber rhizosphere of field-grown sweet potato plants. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2014, 88, 424–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantigoso, H.A.; Manter, D.K.; Fonte, S.J.; Vivanco, J.M. Root exudate-derived compounds stimulate the phosphorus-solubilizing ability of bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shi, X.; Chen, Y.; Yu, J.; Qin, Y.; Jia, L.; Fan, M. Meeting the demand for different nitrogen forms in potato plants without the use of nitrification inhibitors. Plants 2024, 13, 3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Yield | NO3−-N | NH4+-N | AK | AP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield | 1.000 | ||||

| NO3−-N | 0.067 | 1.000 | |||

| NH4+-N | 0.144 | 0.375 * | 1.000 | ||

| AK | 0.570 ** | 0.458 * | −0.078 | 1.000 | |

| AP | 0.132 | 0.037 | −0.01 | 0.585 ** | 1.000 |

| Different Root Zones | Interaction Effect | Degrees of Freedom | F Value | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield | Year × treatment | 4 | 0.124 | p > 0.05 | |

| Nitrate Nitrogen | Bulk soil | Year × treatment | 4 | 0.844 | p > 0.05 |

| Taproot Rhizospheresoil | Year × treatment | 4 | 0.275 | p > 0.05 | |

| Lateral Rhizosphere soil | Year × treatment | 4 | 0.825 | p > 0.05 | |

| Tuber Rhizosphere soil | Year × treatment | 4 | 0.271 | p > 0.05 | |

| Ammonium Nitrogen | Bulk soil | Year × treatment | 4 | 0.475 | p > 0.05 |

| Taproot Rhizospheresoil | Year × treatment | 4 | 0.006 | p > 0.05 | |

| Lateral Rhizosphere soil | Year × treatment | 4 | 0.117 | p > 0.05 | |

| Tuber Rhizosphere soil | Year × treatment | 4 | 0.007 | p > 0.05 | |

| Available Potassium | Bulk soil | Year × treatment | 4 | 0.837 | p > 0.05 |

| Taproot Rhizospheresoil | Year × treatment | 4 | 0.391 | p > 0.05 | |

| Lateral Rhizosphere soil | Year × treatment | 4 | 1.657 | p > 0.05 | |

| Tuber Rhizosphere soil | Year × treatment | 4 | 2.644 | p > 0.05 | |

| Available Phosphorus | Bulk soil | Year × treatment | 4 | 1.551 | p > 0.05 |

| Taproot Rhizospheresoil | Year × treatment | 4 | 0.356 | p > 0.05 | |

| Lateral Rhizosphere soil | Year × treatment | 4 | 9.968 | p < 0.01 | |

| Tuber Rhizosphere soil | Year × treatment | 4 | 23.846 | p < 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ge, M.; Gao, K.; Wang, Y.; Ju, M.; Li, Z.; Hai, X.; Liu, X. Leaf Removal Enhances Tuber Yield in Jerusalem Artichoke by Modulating Rhizosphere Nutrient Availability. Agronomy 2026, 16, 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16020266

Ge M, Gao K, Wang Y, Ju M, Li Z, Hai X, Liu X. Leaf Removal Enhances Tuber Yield in Jerusalem Artichoke by Modulating Rhizosphere Nutrient Availability. Agronomy. 2026; 16(2):266. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16020266

Chicago/Turabian StyleGe, Meijiao, Kai Gao, Yadong Wang, Mingxiu Ju, Ziwei Li, Xinwei Hai, and Xiaoyang Liu. 2026. "Leaf Removal Enhances Tuber Yield in Jerusalem Artichoke by Modulating Rhizosphere Nutrient Availability" Agronomy 16, no. 2: 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16020266

APA StyleGe, M., Gao, K., Wang, Y., Ju, M., Li, Z., Hai, X., & Liu, X. (2026). Leaf Removal Enhances Tuber Yield in Jerusalem Artichoke by Modulating Rhizosphere Nutrient Availability. Agronomy, 16(2), 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16020266