Spray Deposition on Nursery Apple Plants as Affected by an Air-Assisted Boom Sprayer Mounted on a Portal Tractor

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental System Based on a Portal Tractor for Fruit-Tree Nurseries

2.2. Field Crop Sprayer with Air-Assisting

2.3. Air Velocity Measurements

2.4. Spray Deposit-Field Experiment

2.5. Spray Deposit-Laboratory Measurements

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Air Distribution Measurements—Indoor Tests

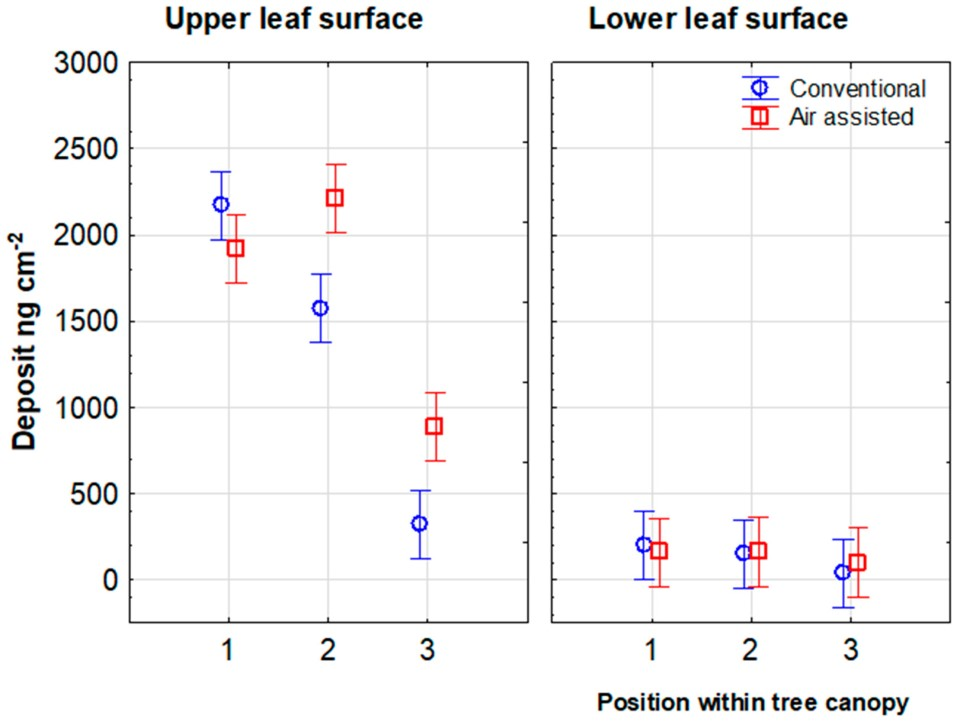

3.2. Spray Deposit

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, H.; Derksen, R.C.; Guler, H.; Krause, C.R.; Ozkan, H.E. Foliar Deposition and Off-Target Loss with Different Spray Techniques in Nursery Applications. Trans. ASABE 2006, 49, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, C.R.; Zhu, H.; Fox, R.D.; Brazee, R.D.; Derksen, R.C.; Horst, L.E.; Zondag, R.H. Detection and Quantification of Nursery Spray Penetration and Off-Target Loss with Electron Beam and Conductivity Analysis. Trans. ASAE 2004, 47, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Cui, H.; Yuan, J. Research Progress and Trend Analysis of Crop Canopy Droplet Deposition. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2021, 52, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Zhu, H.; Ding, W.; Wang, X. Characterization of Air Profiles Impeded by Plant Canopies for a Variable-Rate Air-Assisted Sprayer. Trans. ASABE 2014, 57, 1307–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.E. Highly Maneuverable Nursery Straddle Vehicle. Trans. ASAE 1985, 28, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, Z.; Jia, W.; Ou, M.; Dong, X.; Zhang, Z. A Review on the Evolution of Air-Assisted Spraying in Orchards and the Associated Leaf Motion During Spraying. Agriculture 2025, 15, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foqué, D.; Pieters, J.G.; Nuyttens, D. Spray Deposition and Distribution in a Bay Laurel Crop as Affected by Nozzle Type, Air Assistance and Spray Direction When Using Vertical Spray Booms. Crop Prot. 2012, 41, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallinga, H.; Michielsen, J.M.; Snoussi, M.; van Steenbergen, G. Recovery and Stability of Fluorescent Tracer Acid Yellow 250; Wageningen University & Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2024; Volume 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szarka, Z.A.; Kruger, G.R.; Golus, J.; Rodgers, C.; Perkins, D.; Brain, R.A. Spray Drift Deposition Comparison of Fluorimetry and Analytical Confirmation Techniques. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 4192–4199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, F.; Dou, H.; Zhai, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, W.; Hao, J. Design and Experiment of Or-chard Air-Assisted Sprayer with Airflow Graded Control. Agronomy 2025, 15, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Brazee, R.D.; Derksen, R.C.; Fox, R.D.; Krause, C.R.; Ozkan, H.E.; Losely, K. A Specially Designed Air-Assisted Sprayer to Improve Spray Penetration and Air Jet Velocity Distribution Inside Dense Nursery Crops. Trans. ASABE 2006, 49, 1285–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Development of an Intelligent Sprayer to Optimize Pesticide Applications in Nurseries and Orchards. Ph.D. Dissertation, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Dong, X.; Yan, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, T.; Zeng, Y. Experiment on Spraying Performance of Air-Assisted Boom Sprayer in Corn Field. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2015, 46, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derksen, R.C.; Krause, C.R.; Zondag, R.H.; Reding, M.E.; Fox, R.D. Effect of Application Variables on Spray Deposition, Coverage, and Ground Losses in Nursery Tree Applications. J. Environ. Hortic. 2006, 24, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Zondag, R.H.; Derksen, R.C.; Reding, M.E.; Krause, C.R. Influence of Spray Volume on Spray Deposition and Coverage within Nursery Trees. J. Environ. Hortic. 2008, 26, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Liu, H.; Shen, Y.; Zondag, R. Spray Deposition Inside Multiple-Row Nursery Trees with a Laser-Guided Sprayer. J. Environ. Hortic. 2017, 35, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Derksen, R.C.; Krause, C.R.; Fox, R.D.; Brazee, R.D.; Zondag, R.H. Spray Deposition and Off-Target Loss in Nursery Tree Crops with Conventional Nozzle, Air Induction Nozzle and Drift Retardant. In Proceedings of the 2005 ASAE Annual Meeting, Tampa, FL, USA, 17–20 July 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, P.K. Spray Drift and Deposition Uniformity with Conventional Technique and Hardi Twin Air Assistance at Two Wind Speeds. In Applied Crop Protection 2019; DCA Report 167; DCA—Nationalt Center for Fødevarer og Jordbrug: Slagelse, Denmark, 2020; pp. 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Womac, A.R.; Ozkan, E.; Zhu, H.; Kochendorfer, J.; Jeon, H. Status of Spray Penetration and Deposition in Dense Field Crop Canopies. Trans. ASABE 2022, 65, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.Y.; Zhu, H. Development of a Variable-Rate Sprayer for Nursery Liner Applications. Trans. ASABE 2012, 55, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piché, M.; Panneton, B.; Thériault, R. Field Evaluation of Air-Assisted Boom Spraying on Broccoli and Potato. Trans. ASAE 2000, 43, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fessler, L.; Fulcher, A.; Schneider, L.; Wright, W.C.; Zhu, H. Reducing the Nursery Pesticide Footprint with Laser-Guided, Variable-Rate Spray Application Technology. HortScience 2021, 56, 1572–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derksen, R.C.; Krause, C.R.; Zondag, R.H.; Reding, M.E.; Fox, R.D. Spray Delivery to Nursery Trees by Air Curtain and Axial Fan Orchard Sprayers. J. Environ. Hortic. 2004, 22, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salyani, M.; Miller, D.R.; Farooq, M.; Sweeb, R.D. Effects of Sprayer Operating Parameters on Airborne Drift from Citrus Air-Carrier Sprayers. Agric. Eng. Int. CIGR J. 2013, 15, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, J.P.; Chueca, P.; Garcerá, C.; Moltó, E. Risk Assessment of Pesticide Spray Drift from Citrus Applications with Air-Blast Sprayers in Spain. Crop Prot. 2012, 42, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foqué, D.; Dekeyser, D.; Zwertvaegher, I.; Nuyttens, D. Accuracy of a Multiple Mineral Tracer Methodology for Measuring Spray Deposition. Asp. Appl. Biol. 2014, 122, 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Foqué, D.; Nuyttens, D. Effects of Nozzle Type and Spray Angle on Spray Deposition in Ivy Pot Plants. Pest Manag. Sci. 2011, 67, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuyttens, D.; Windey, S.; Sonck, B. Optimisation of a Vertical Spray Boom for Green-house Spray Applications. Biosyst. Eng. 2004, 89, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, M.; Wang, C.; Dai, S.; Wang, M.; Dong, X.; Jiang, L. Development and Experiment of an Air-Assisted Sprayer for Vineyard Pesticide Application. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ramos, F.J.; Vidal, M.; Boné, A.; Malón, H.; Aguirre, J. Analysis of the Air Flow Generated by an Air-Assisted Sprayer Equipped with Two Axial Fans Using a 3D Sonic Anemometer. Sensors 2012, 12, 7598–7613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekeyser, D.; Foqué, D.; Duga, A.T.; Verboven, P.; Hendrickx, N.; Nuyttens, D. Spray Deposition Assessment Using Different Application Techniques in Artificial Orchard Trees. Crop Prot. 2014, 64, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panneton, B.; Lacasse, B.; Piché, M. Effect of Air-Jet Configuration on Spray Coverage in Vineyards. Biosyst. Eng. 2005, 90, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panneton, B.; Lacasse, B.; Thériault, R. Penetration of Spray in Apple Trees as a Function of Airspeed, Airflow, and Power for Tower Sprayers. Can. Biosyst. Eng. 2005, 47, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, Y.; Sinfort, C. Emission of Pesticides to the Air During Sprayer Application: A Bibliographic Review. Atmos. Environ. 2005, 39, 5183–5193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo, R.; Pons, P.; Llop, J.; Zaragoza, T.; Campos, J.; Ortega, P.; Gallart, M.; Gil, E. Dynamic Evaluation of Airflow Stream Generated by a Reverse System of an Axial Fan Sprayer Using 3D Ultrasonic Anemometers: Effect of Canopy Structure. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 163, 104851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ramos, F.J.; Serreta, A.; Boné, A.; Vidal, M. Applicability of a 3D Laser Scanner for Characterizing the Spray Distribution Pattern of an Air-Assisted Sprayer. J. Sens. 2018, 2018, 5231810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Zande, J.; Barendregt, A.; Michielsen, J.; Stallinga, H. Effect of Sprayer Settings on Spray Distribution and Drift Potential When Spraying Dwarf Apple Trees. In Proceedings of the ASAE Annual International Meeting, Chicago, IL, USA, 28–31 July 2002; p. 021036. [Google Scholar]

- Dekeyser, D.; Duga, A.T.; Verboven, P.; Endalew, A.M.; Hendrickx, N.; Nuyttens, D. Assessment of Orchard Sprayers Using Laboratory Experiments and Computational Fluid Dynamics Modelling. Biosyst. Eng. 2013, 114, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, W.A.; Andersen, P.G. A Review of Benefits of Air-Assisted Spraying Trials in Arable Crops. Asp. Appl. Biol. 1997, 48, 163–173. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Dimensions (length × width × height) | m | 4.0 × 2.21 × 3.97 |

| Ground clearance (front/rear) | m | 1.76/1.73 |

| Wheelbase | m | 2.66 |

| Tire size | – | 9.5-42-0 |

| Drive system Landini Rex 70F, capacity | cm3 | 3300 |

| Engine 3TA diesel, power | kW/HP | 50/68 |

| Torque | Nm | 280 |

| Hydraulic pump capacity | L/min | 52.3 |

| PTO speed | rpm | 540/750 |

| Fuel tank capacity | L | 57 |

| Maximum lifting capacity | kg | 2600 |

| Number of gears (forward/reverse) | – | 12/12 |

| Parameter | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Dimensions (length × width × height) | m | 3.3 × 2.5 × 2.98 |

| Tank capacity | L | 1000 |

| Weight | kg | 850 |

| Power requirement–boom | kW | 6.2 |

| Power requirement–liquid pump | kW | 2.6 |

| Boom–working width | m | 15 |

| Boom–height | m | 0.3–3.0 |

| Airflow rate | m3/m of boom | 0.65 |

| Air velocity (at 0.5 m height) | m/s | 5.5 |

| Spray liquid pump–capacity | L/min | 160 |

| Spray liquid pump–working pressure | MPa | 2.0 |

| Spray Dose L·ha−1 | AA * | Air Velocity m·s−1 | Travel Velocity km∙h−1 | Nozzle Types | Spray Pressure MPa | Spray Flow L·min−1 | Droplets Size (BCPC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 | Off | 5.5 | 6.0 | LU 120-03 | 0.21 | 1.0 | fine |

| On | 5.5 | 6.0 | LU 120-03 | 0.21 | 1.0 | fine | |

| Off | 5.5 | 9.0 | LU 120-03 | 0.38 | 1.5 | fine | |

| On | 5.5 | 9.0 | LU 120-03 | 0.38 | 1.5 | fine | |

| 400 | Off | 5.5 | 6.0 | LU 120-05 | 0.31 | 2.0 | fine |

| On | 5.5 | 6.0 | LU 120-05 | 0.31 | 2.0 | fine | |

| Off | 5.5 | 9.0 | LU 120-05 | 0.59 | 3.0 | fine | |

| On | 5.5 | 9.0 | LU 120-05 | 0.59 | 3.0 | fine |

| Fan Speed | Oil Pressure Inlet | Oil Pressure Outlet | Oil Flow | Power Consumption |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rpm | MPa | MPa | L/min | kW |

| 1411 | 7.2 | 0.4 | 22.40 | 2.54 |

| 1503 | 7.9 | 0.4 | 23.79 | 2.97 |

| 1608 | 8.7 | 0.5 | 25.73 | 3.52 |

| 1721 | 9.6 | 0.5 | 27.58 | 4.18 |

| 1816 | 10.5 | 0.5 | 29.24 | 4.87 |

| 1904 | 11.3 | 0.5 | 30.59 | 5.51 |

| 2003 | 12.1 | 0.6 | 32.32 | 6.19 |

| Spray Dose L·ha−1 | AA * | Travel Velocity km·h−1 | Wind Velocity m·s−1 | Air Humidity % | Temperature °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 | Off | 6.0 | 0.6–1.2 | 54.1 | 18 |

| On | 6.0 | 1.6–1.8 | 53.8 | 19 | |

| Off | 9.0 | 1.3–1.8 | 52.8 | 22 | |

| On | 9.0 | 0.5–0.8 | 44.5 | 21 | |

| 400 | Off | 6.0 | 0.6–0.9 | 44.5 | 22 |

| On | 6.0 | 0.4–0.9 | 44.0 | 21 | |

| Off | 9.0 | 0.4–1.0 | 41.1 | 22 | |

| On | 9.0 | 0.7–1.2 | 39.9 | 22 |

| Source of Variation | Sum of Squares | df | Percent of Total | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 10,715.67 | 1 | 0 | |

| Spray volume | 4.49 | 1 | 0.041901253 | 0.002199 |

| Speed | 6.16 | 1 | 0.057485906 | 0.000342 |

| Emission | 14.33 | 1 | 0.133729389 | 0 |

| Leaf side | 371.28 | 1 | 3.464832344 | 0 |

| Spray volume × Speed | 3.6 | 1 | 0.033595659 | 0.006014 |

| Spray volume × Emission | 0.18 | 1 | 0.001679783 | 0.532112 |

| Speed × Emission | 0.88 | 1 | 0.008212272 | 0.173612 |

| Spray volume × Leaf side | 3.92 | 1 | 0.036581940 | 0.004168 |

| Speed × Leaf side | 0.06 | 1 | 0.000559928 | 0.729433 |

| Emission × Leaf side | 0.04 | 1 | 0.000373285 | 0.761084 |

| Spray volume × Speed × Emission | 0.08 | 1 | 0.000746570 | 0.685630 |

| Spray volume × Speed × Emission | 0.09 | 1 | 0.000839891 | 0.660784 |

| Spray volume × Emission × Leaf side | 0.69 | 1 | 0.006439168 | 0.229144 |

| Speed × Emission × Leaf side | 1.17 | 1 | 0.010918589 | 0.117129 |

| Spray volume × Speed × Emission × Leaf side | 0.11 | 1 | 0.001026534 | 0.623816 |

| Error | 196.57 | 416 |

| Efekt | Sum of Squares | df | p | Percent of Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 10,715.67 | 1 | 0 | |

| Emission | 14.33 | 1 | 0 | 0.133729389 |

| Position | 77.05 | 2 | 0 | 0.719040433 |

| Leaf side | 371.28 | 1 | 0 | 3.464832344 |

| Emission × Position | 8.32 | 2 | 0.000002 | 0.077643302 |

| Emission × Leaf side | 0.04 | 1 | 0.704935 | 0.000373285 |

| Position × Leaf side | 4.21 | 2 | 0.001117 | 0.039288257 |

| Emission × Position × Leaf side | 0.47 | 2 | 0.466606 | 0.004386100 |

| Error | 127.95 | 420 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hołownicki, R.; Doruchowski, G.; Świechowski, W.; Godyń, A.; Konopacki, P.; Bartosik, A.; Białkowski, P. Spray Deposition on Nursery Apple Plants as Affected by an Air-Assisted Boom Sprayer Mounted on a Portal Tractor. Agronomy 2026, 16, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010008

Hołownicki R, Doruchowski G, Świechowski W, Godyń A, Konopacki P, Bartosik A, Białkowski P. Spray Deposition on Nursery Apple Plants as Affected by an Air-Assisted Boom Sprayer Mounted on a Portal Tractor. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleHołownicki, Ryszard, Grzegorz Doruchowski, Waldemar Świechowski, Artur Godyń, Paweł Konopacki, Andrzej Bartosik, and Paweł Białkowski. 2026. "Spray Deposition on Nursery Apple Plants as Affected by an Air-Assisted Boom Sprayer Mounted on a Portal Tractor" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010008

APA StyleHołownicki, R., Doruchowski, G., Świechowski, W., Godyń, A., Konopacki, P., Bartosik, A., & Białkowski, P. (2026). Spray Deposition on Nursery Apple Plants as Affected by an Air-Assisted Boom Sprayer Mounted on a Portal Tractor. Agronomy, 16(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010008