Liming Alters Microbial Communities Affecting Nitrification in the Rhizosphere of Camellia sinensis

Abstract

1. Instruction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experiment Site and Sampling

2.2. Soil Property Analyses

2.3. Soil DNA Extraction and Real-Time PCR Assay

2.4. Microbial Community Analysis by High-Throughput Sequencing

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Liming on Soil Physicochemical Properties

3.2. Effects of Liming on Soil Microbial Biomass

3.3. Effects of Liming on Soil Microbial Diversity

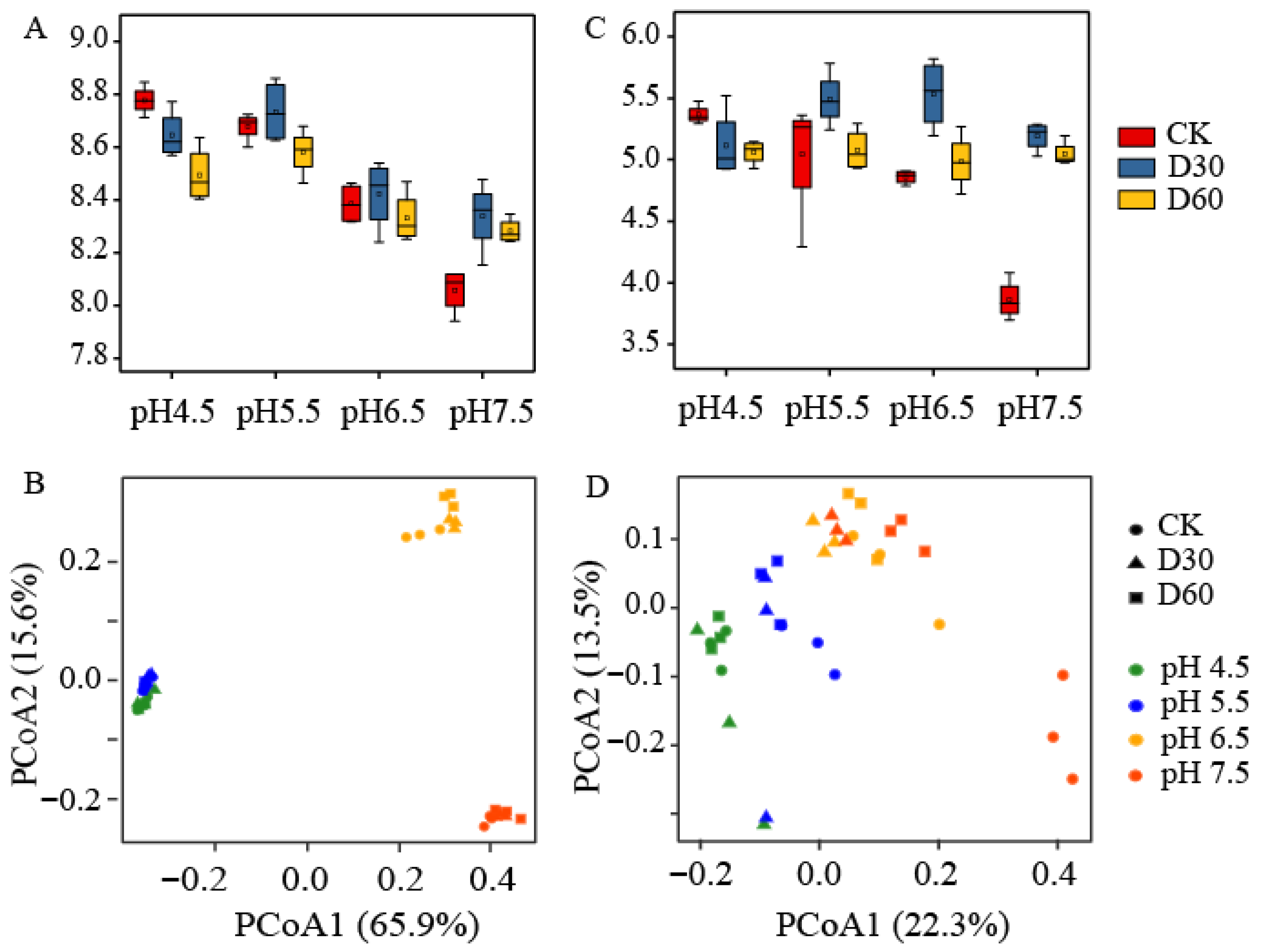

3.4. Effects of Liming on Soil Microbial Community Composition

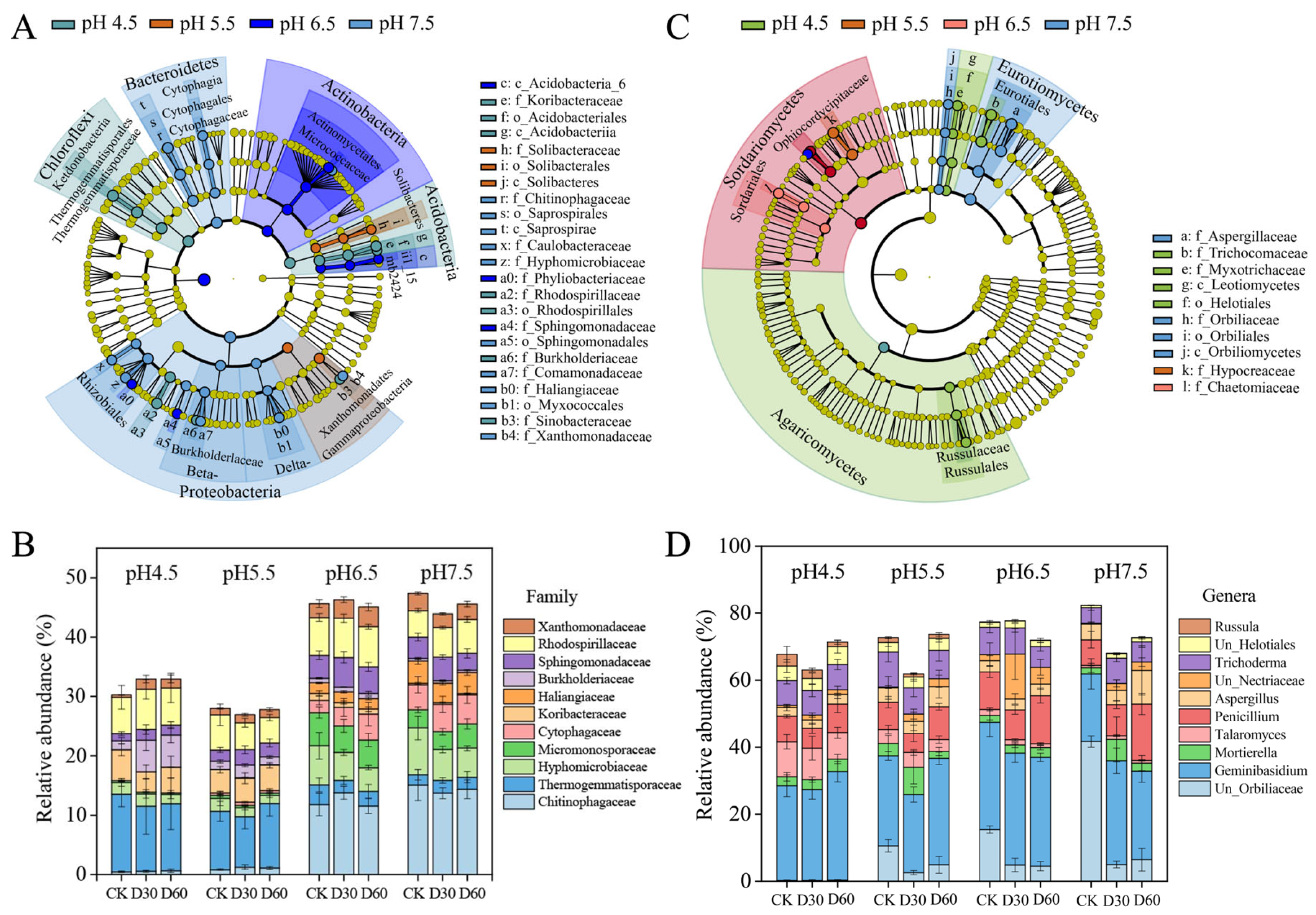

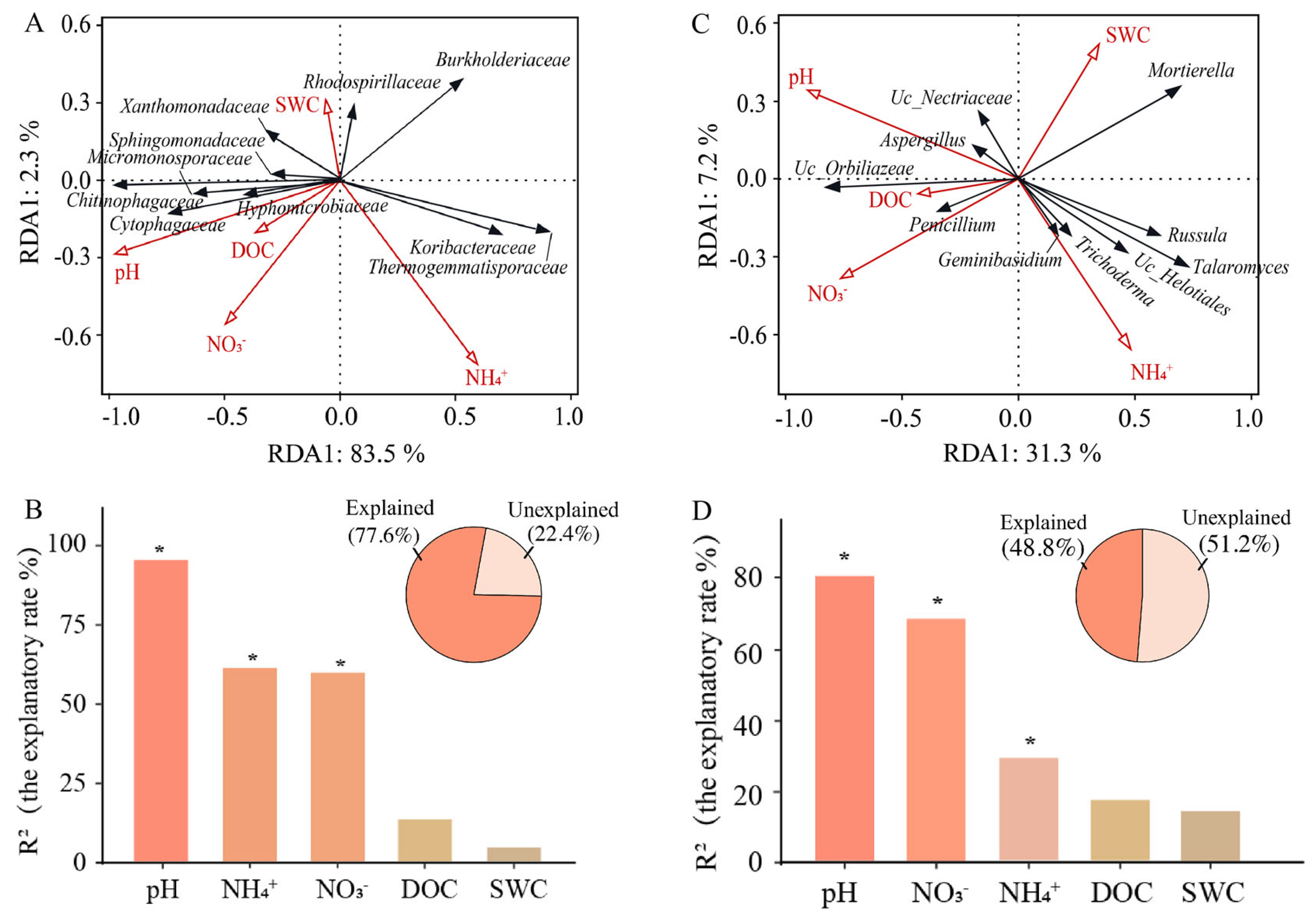

3.5. The Correlation Between Dominant Microbial Groups and Environmental Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Liming Significantly Influenced the Activity of Soil Microorganisms

4.2. Liming Significantly Influenced the Dominant Taxa of Bacteria and Fungi

4.3. Potential Links Between Microbes and Different Edaphic Properties

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Philippot, L.; Chenu, C.; Kappler, A.; Rillig, M.C.; Fierer, N. The interplay between microbial communities and soil properties. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beugnon, R.; Du, J.; Cesarz, S.; Jurburg, S.D.; Pang, Z.; Singavarapu, B.; Wubet, T.; Xue, K.; Wang, Y.; Eisenhauer, N. Tree diversity and soil chemical properties drive the linkages between soil microbial community and ecosystem functioning. ISME Commun. 2021, 1, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Dai, S.; Huang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Cheng, Y.; Cai, Z.; Zhang, J. pH-induced changes in fungal abundance and composition affects soil heterotrophic nitrification after 30 days of artificial pH manipulation. Geoderma 2020, 366, 114255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, K.; Cardona, C.; Li, Y.; Shi, Y.; Xiang, X.; Shen, C.; Wang, H.; Gilbert, J.A.; Chu, H. Rhizosphere-associated bacterial network structure and spatial distribution differ significantly from bulk soil in wheat crop fields. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 113, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.B.; Cai, Z.C.; Zhu, T.B.; Yang, W.; Müller, C. Mechanisms for the retention of inorganic N in acidic forest soils of southern China. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, S.; Mohanty, B.P.; Malik, A.A. Soil microorganisms regulate extracellular enzyme production to maximize their growth rate. Biogeochemistry 2022, 158, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spohn, M.; Braun, S.; Sierra, C.A. Continuous decrease in soil organic matter despite increased plant productivity in an 80-years-old phosphorus-addition experiment. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, F.A.; Bader, N.E.; Johnson, D.W.; Cheng, W.X. Does accelerated soil organic matter decomposition in the presence of plants increase plant N availability? Soil Biol. Biochem. 2009, 41, 1080–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomako, M.O.; Roiloa, S.; Yu, F.H. Potential roles of soil microorganisms in regulating the effect of soil nutrient heterogeneity on plant performance. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Bai, H.; Zhao, C.H.; Peng, M.; Chi, Q.; Dai, Y.P.; Gao, F.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, M.M.; Niu, B. The characteristics of soil microbial co-occurrence networks across a high-latitude forested wetland ecotone in China. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1160683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.X.; Zhang, X.Q.; Chen, H.Y.; Jiang, Y.H.; Zhang, J.G. Effects of forest age and season on soil microbial communities in Chinese fir plantations. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, 0407523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zhang, D.; Xu, G.; Yan, R.; Huang, Y.; Feng, L.; Yi, J.; Xue, X.; Liu, H. Effects of Alpine Grassland Degradation on Soil Microbial Communities in Qilian Mountains of China. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 912–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.W.; Du, S.Y.; Guo, H.J.; Min, W. Long-term saline water drip irrigation alters soil physicochemical properties, bacterial community structure, and nitrogen transformations in cotton. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 182, 104719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Cui, H.; Liu, Q.; Wang, F.; Liao, H.; Lu, P.; Qin, S. Effect of nitrogen reduction by chemical fertilization with green manure (Vicia sativa L.) on soil microbial community, nitrogen metabolism and and yield of Uncaria rhynchophylla by metagenomics. Arch. Microbiol. 2024, 206, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.B.; He, H.B.; Zhang, X.D.; Yan, X.Y.; Johan, S.; Cai, Z.C.; Matti, B.; Zhang, J.B.; Magdalena, N.; Ma, Q.Q.; et al. Distinct responses of soil fungal and bacterial nitrate immobilization to land conversion from forest to agriculture. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 134, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseeva, T.; Alekseev, A.; Xu, R.K.; Zhao, A.-Z.; Kalinin, P. Effect of soil acidification induced by a tea plantation on chemical and mineralogical properties of Alfisols in eastern China. Environ. Geochem. Health 2011, 33, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.E.; Bennett, A.E.; Newton, A.C.; White, P.J.; McKenzie, B.M.; George, T.S.; Pakeman, R.J.; Bailey, J.S.; Fornara, D.A.; Hayes, R.C. Liming impacts on soils, crops and biodiversity in the UK: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 610–611, 316–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Zhou, J.; Pan, W.; Tang, R.; Ma, Q.; Xu, M.; Qi, T.; Ma, Z.; Fu, H.; Wu, L. Impact of N application rate on tea (Camellia sinensis) growth and soil bacterial and fungi communities. Plant Soil. 2022, 475, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isobe, K.; Koba, K.; Suwa, Y.; Ikutani, J.; Kuroiwa, M.; Fang, Y.; Yoh, M.; Mo, J.; Otsuka, S.; Senoo, K. Nitrite transformations in an N-saturated forest soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 52, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onodera, Y.; Nakagawa, T.; Takahashi, R.; Tokuyama, T. Seasonal change in vertical distribution of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria and their nitrification in temperate forest soil. Microbes Environ. 2010, 25, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Li, M.; Shi, W.; Tian, R.; Chang, C.; Wang, Z.; Wang, N.; Zhao, G.; Gao, Z. Similar drivers but different effects lead to distinct ecological patterns of soil bacterial and archaeal communities. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 144, 107759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, K.; Jinnai, K.; Sakiyama, Y.; Touma, M. Contribution of fungi to acetylene-tolerant and high ammonia availability-dependent nitrification potential in tea field soils with relatively neutral pH. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2012, 62, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Jiang, H.J.; Pan, Y.T.; Lu, F.; Zhu, Q.; Ma, C.Y.; Zhang, A.Y.; Zhou, J.Y.; Zhang, W.; Dai, C.C. Hyphosphere microorganisms facilitate hyphal spreading and root colonization of plant symbiotic fungus in ammonium-enriched soil. ISME. J. 2023, 17, 1626–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaliq, A.; Perveen, S.; Alamer, K.H.; Zia, U.; Haq, M.; Rafique, Z.; Alsudays, I.M.; Althobaiti, A.T.; Saleh, M.A.; Hussain, S.; et al. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Symbiosis to Enhance Plant-Soil Interaction. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Zou, J.; Zhang, B.; Wu, L.; Yang, T.; Huang, Q. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Microbes Interaction in Rice Mycorrhizosphere. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, P.; Bora, L.C. Microbial antagonists and botanicals mediated disease management in tea, Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze: An overview. Crop Prot. 2021, 148, 105711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, B.; Huang, X.; Yang, L.; Lan, T.; Zhang, J.; Cai, Z. Comparative soil microbial communities and activities in adjacent Sanqi ginseng monoculture and Maize-Sanqi ginseng systems. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2017, 120, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.Q.; Wen, T.; Zhang, J.B.; Meng, L.; Zhu, T.B.; Liu, L.L.; Cai, Z.C. Control of soil-borne pathogen Fusarium oxysporum by biological soil disinfestation with incorporation of various organic matters. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2015, 143, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousk, J.; Bååth, E.; Brookes, P.; Lauber, C.L.; Lozupone, C.; Caporaso, J.G.; Knight, R.; Fierer, N. Soil bacterial and fungal communities across a pH gradient in an arable soil. ISME. J. 2010, 4, 1340–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, S.; Sikorski, J.; Dietz, S.; Herz, K.; Schrumpf, M.; Bruelheide, H.; Scheel, D.; Friedrich, M.W.; Overmann, J. Drivers of the composition of active rhizosphere bacterial communities in temperate grasslands. ISME. J. 2020, 14, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Sun, L.; Gan, D.; Fu, L.; Zhu, B. Root functional traits are key determinants of the rhizosphere effect on soil organic matter decomposition across 14 temperate hardwood species. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 151, 108019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, G.W.; Leininger, S.; Schleper, C.; Prosser, J.I. The influence of soil pH on the diversity, abundance and transcriptional activity of ammonia oxidizing archaea and bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 10, 2966–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, J.; Li, X.; Wang, N.; Lan, Z.; He, J.; Bai, Y. Contrasting effects of nitrogen forms and soil pH on ammonia oxidizing microorganisms and their responses to long-term nitrogen fertilization in a typical steppe ecosystem. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 107, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hink, L.; Gubry-Rangin, C.; Nicol, G.W.; Prosser, J.I. The consequences of niche and physiological differentiation of archaeal and bacterial ammonia oxidizers for nitrous oxide emissions. ISME. J. 2018, 12, 1084–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, W.; Ni, Z.; Hashidoko, Y.; Shen, W. Ammonium nitrogen content is a dominant predictor of bacterial community composition in an acidic forest soil with exogenous nitrogen enrichment. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 624, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierer, N. Embracing the unknown: Disentangling the complexities of the soil microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.F.; Vilgalys, R.; Kuske, C.R. Changes in fungal community composition in response to elevated atmospheric CO2 and nitrogen fertilization varies with soil horizon. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrion, V.J.; Cordovez, V.; Tyc, O.; Etalo, D.W.; de Bruijn, I.; de Jager, V.C.L.; Medema, M.H.; Eberl, L.; Raaijmakers, J.M. Involvement of Burkholderiaceae and sulfurous volatiles in disease-suppressive soils. ISME J. 2018, 12, 2307–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Brookes, P.C.; Xu, J.; Luo, Y. Interactive effects of soil pH and substrate quality on microbial utilization. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2020, 96, 103151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallenda, T.; Kottke, I. Nitrogen deposition and ectomycorrhizas. New Phytol. 1998, 139, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target Gene | Primer Set | Sequence (5′-3′) | Thermal Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial 16S | Eub338 (F) | ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG | 2 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 10 s at 95 °C, 20 s at 53 °C, and 30 s at 72 °C |

| Eub518 (R) | ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGG | ||

| Fungal ITS | ITS1 (F) | TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG | 2 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 10 s at 95 °C, 20 s at 53 °C, and 30 s at 72 °C |

| ITS2 (R) | CGCTGCGTTCTTCATCG |

| Soil Type | pH | NH4+ (mg kg−1) | NO3− (mg kg−1) | DOC (mg kg−1) | SWC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 4.15 | 31.01 ± 0.66 cC | 48.47 ± 1.14 bA | 66.86 ± 1.01 cC | 25.83 ± 0.19 aA | |

| pH 4.5 | D30 | 4.18 | 16.66 ± 0.64 bC | 43.53 ± 2.48 aA | 37.42 ± 3.89 bA | 25.06 ± 0.47 aA |

| D60 | 4.09 | 10.38 ± 1.31 aA | 50.05 ± 5.31 bB | 17.98 ± 3.38 aA | 28.7 ± 1.15 bA | |

| CK | 5.36 | 30.02 ± 0.71 cC | 44.25 ± 4.32 aA | 73.94 ± 2.96 cD | 26.38 ± 0.25 bA | |

| pH 5.5 | D30 | 5.35 | 18.53 ± 1.63 bC | 52.37 ± 4.77 bB | 40.87 ± 11.56 bA | 24.56 ± 0.12 aA |

| D60 | 5.19 | 12.35 ± 0.66 aB | 42.2 ± 1.14 aA | 21.21 ± 1.01 aA | 28.32 ± 0.19 cA | |

| CK | 6.83 | 14.92 ± 0.12 cB | 106.04 ± 4.8 bB | 52.33 ± 2.06 bA | 26.01 ± 0.26 bA | |

| pH 6.5 | D30 | 6.89 | 12.14 ± 0.17 bB | 71.24 ± 2.79 aB | 49.57 ± 1.86 bA | 24.79 ± 0.34 aA |

| D60 | 6.73 | 11.27 ± 0.72 aAB | 65.93 ± 6.45 aC | 39.87 ± 7.01 aB | 29.69 ± 1.26 cA | |

| CK | 7.74 | 13.44 ± 0.83 bA | 109.88 ± 2.09 bB | 59.15 ± 2.49 aB | 25.25 ± 0.17 aA | |

| pH 7.5 | D30 | 7.79 | 9.79 ± 0.45 aA | 76.38 ± 13.11 aB | 62.74 ± 5.03 aB | 25.02 ± 0.05 aA |

| D60 | 7.74 | 9.57 ± 0.57 aA | 72.49 ± 11.98 aC | 52.63 ± 5.83 aC | 29.78 ± 0.33 bA | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhao, C.; He, X.; Jiang, H.; Wang, X.; Gao, J.; Hu, C. Liming Alters Microbial Communities Affecting Nitrification in the Rhizosphere of Camellia sinensis. Agronomy 2026, 16, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010077

Zhao C, He X, Jiang H, Wang X, Gao J, Hu C. Liming Alters Microbial Communities Affecting Nitrification in the Rhizosphere of Camellia sinensis. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010077

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Chang, Xiaoxiang He, Han Jiang, Xiaoyan Wang, Jinjuan Gao, and Chanjuan Hu. 2026. "Liming Alters Microbial Communities Affecting Nitrification in the Rhizosphere of Camellia sinensis" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010077

APA StyleZhao, C., He, X., Jiang, H., Wang, X., Gao, J., & Hu, C. (2026). Liming Alters Microbial Communities Affecting Nitrification in the Rhizosphere of Camellia sinensis. Agronomy, 16(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010077