3.1. Cluster Analysis of Vegetation Under the Influence of Organic and Mineral Fertilization

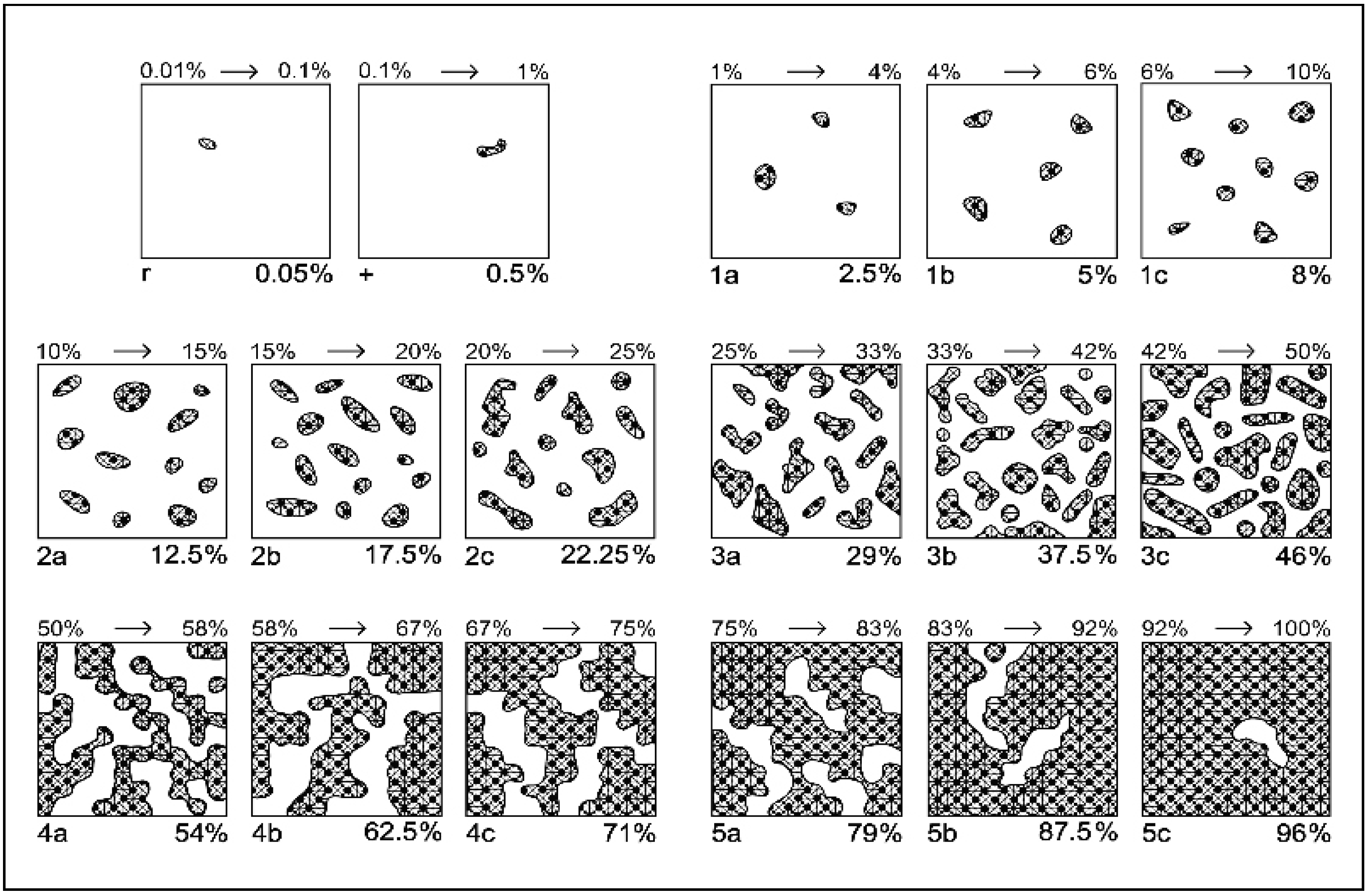

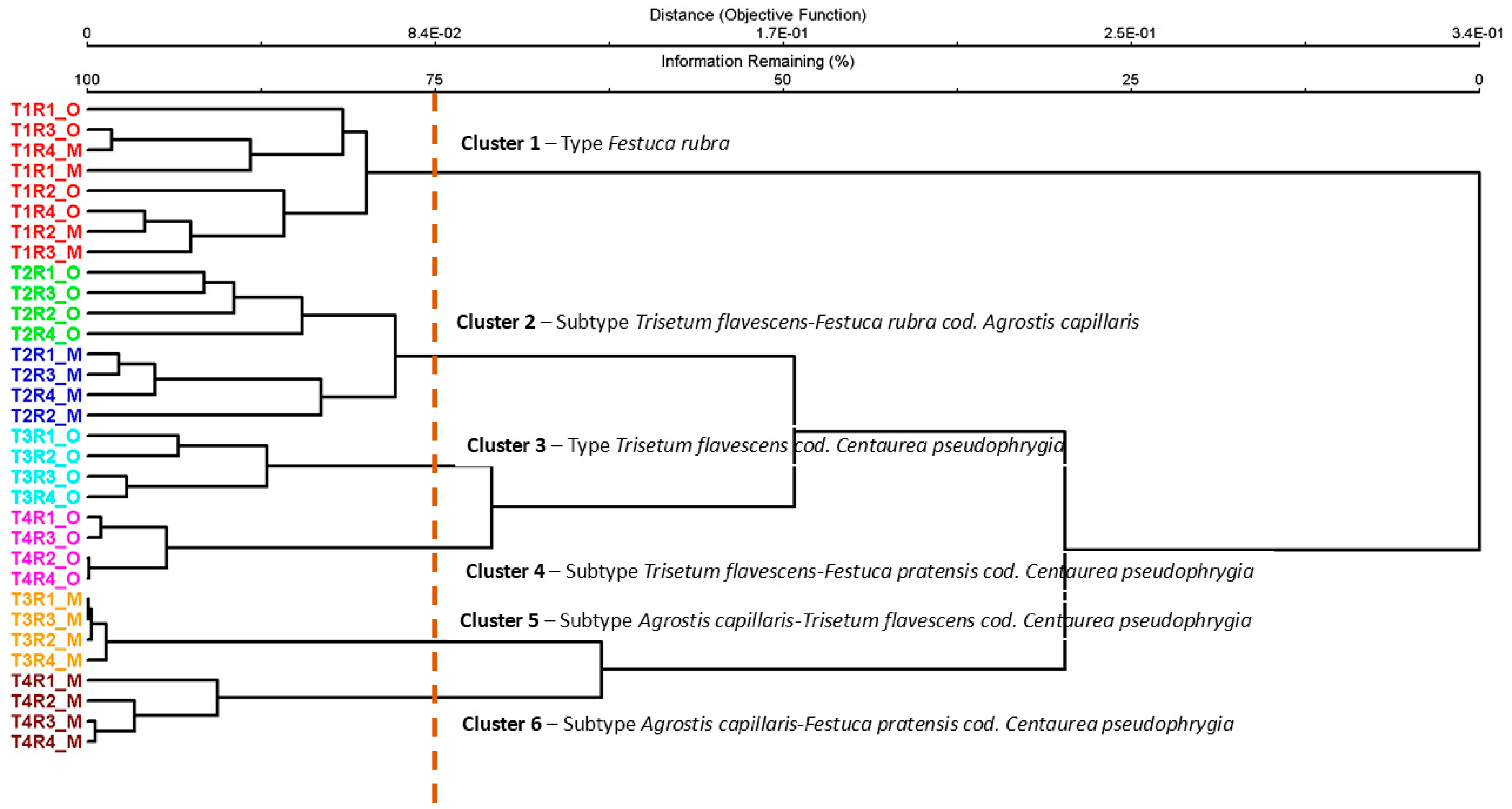

The application of organic and mineral fertilization produced clear shifts in the floristic composition of mountain grasslands, as reflected by the separation of the experimental plots into six distinct vegetation groups corresponding to a well-defined trophic gradient (

Figure 2). The hierarchical classification (Sørensen–Bray–Curtis index, UPGMA method) accurately reflected both the intensity and type of fertilization inputs, with the number of clusters being selected based on ecological interpretability and further supported by congruent patterns revealed by ISA and PCoA analyses. Multivariate analyses were performed using PC-ORD v.7.

Cluster 1 (Festuca rubra type) comprises all control plots from both experiments, organic and mineral (T1R1–T1R4_O and T1R1–T1R4_M). These communities are dominated by F. rubra and represent typical oligotrophic mountain grasslands, characterized by high floristic diversity, structural stability, and a large proportion of perennial stress-tolerant species adapted to nutrient-poor conditions. Although T2_O (10 t ha−1 manure) and T2_M (N50P25K25) were grouped together in Cluster 2 owing to their overall floristic similarity, the MRPP results indicated that the two treatments still differed significantly in species composition (T = −3.257, A = 0.166, p = 0.0089). This confirms that similar vegetation types may emerge from different nutrient sources while retaining subtle, but statistically relevant, floristic distinctions. Cluster 2 (Subtype Trisetum flavescens–Festuca rubra cod. Agrostis capillaris) included both variants fertilized with 10 t ha−1 manure (T2_O) and those fertilized with N50P25K25 (T2_M). This grouping indicates that moderate fertilization, whether organic or mineral, produces similar ecological effects on dominant species and community structure. In these plots, T. flavescens became dominant, F. rubra remained co-dominant, and A. capillaris was strongly promoted, becoming an additional co-dominant species. The coexistence of these three species defines a derived subtype within the broader F. rubra type, representing a transition toward mesotrophic grasslands with increased productivity but without major losses in floristic diversity.

Cluster 3 (Type Trisetum flavescens cod. Centaurea pseudophrygia) corresponds to the variant fertilized with 20 t ha−1 manure (T3_O). Higher organic input strengthened T. flavescens as the dominant species and promoted the consistent presence of C. pseudophrygia as a codominant species. This pattern reflects a clear shift toward mesotrophic grasslands, characterized by increased biomass production and a more uniform, yet balanced, floristic structure. Cluster 4 (Subtype T. flavescens–Festuca pratensis cod. C. pseudophrygia) includes the variant fertilized with 30 t ha−1 manure (T4_O). Intensification of organic input enhances the dominance of productive species, such as F. pratensis and T. flavescens, whereas C. pseudophrygia remains a characteristic element. This subtype represents a logical development of the T. flavescens type, indicating a progression toward higher mesotrophic conditions and a decline in the proportion of conservative species.

Cluster 5 (Subtype A.s capillaris–T. flavescens cod. C. pseudophrygia) groups the plots fertilized with N100P50K50 (T3_M). These communities exhibit a structure similar to that observed under moderate organic fertilization but show a stronger influence of nitrophilous species owing to the rapid availability of mineral nutrients. Increased competitive pressure favors A. capillaris and contributes to reduced floristic diversity. This subtype is also derived from T. flavescens. Cluster 6 (Subtype A. capillaris–F. pratensis cod. C. pseudophrygia) consists of the plots with the highest level of mineral fertilization (T4_M). These communities are dominated by A.s capillaris and F. pratensis, whereas C. pseudophrygia is a characteristic species of eutrophicated grasslands. Reduced diversity and increased floristic uniformity reflect the effects of strong eutrophication. Overall, the dendrogram highlights a coherent trophic gradient, ranging from oligotrophic F. rubra grasslands in the control variants to mesotrophic and eutrophic grasslands dominated by A. capillaris and F. pratensis under intensive mineral fertilization conditions. These results were fully supported by PCoA, which confirmed the same floristic groupings along the fertilization gradient.

3.2. Spatial Distance in Plant Community Projection Due to Long-Term Fertilization Organic and Mineral

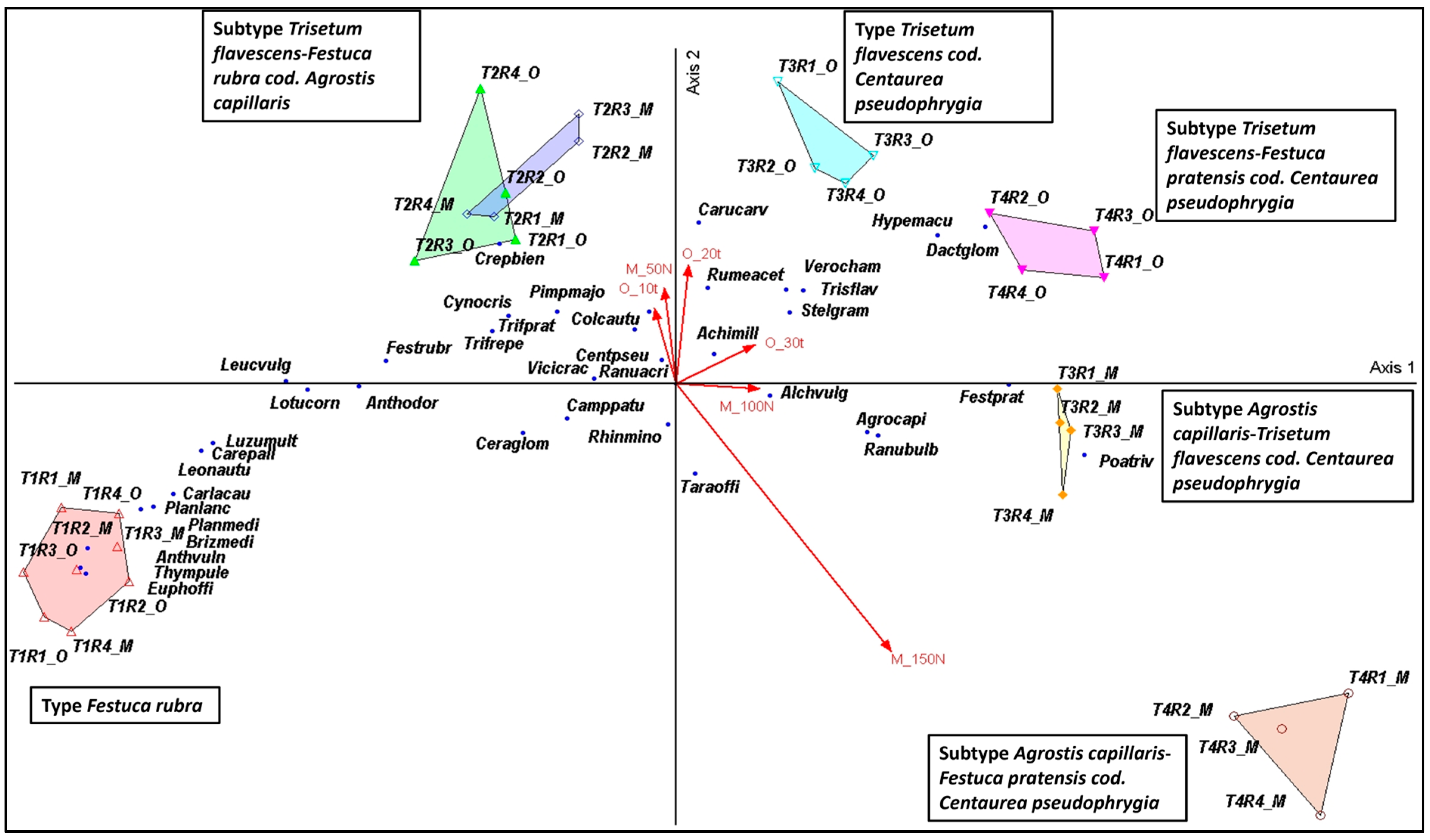

The coherent trophic gradient identified by cluster analysis was further corroborated and spatially visualized through Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) based on the Bray–Curtis distance, which revealed a clear separation of grassland communities according to fertilization intensity (

Figure 3). The first two axes explained 93% of the total variation in floristic composition (

Table 4), confirming that the trophic gradient induced by long-term fertilization is the primary factor structuring the mountain grassland vegetation. Axis 1, which accounted for the overwhelming proportion of variance (r = 0.876), accurately described the floristic transition from oligotrophic grasslands toward highly eutrophicated communities. On the negative side of Axis 1, the control variants (T1_O, T1_M) and treatments with low organic fertilization (T2_O) clustered together, corresponding to the

F. rubra grassland type. These communities are characterized by low-productive mountain grasslands dominated by species adapted to nutrient-poor conditions. Representative species include

F. rubra,

Carex pallescens,

Luzula multiflora,

Leontodon autumnalis,

Polygala vulgaris,

Briza media,

Plantago media,

Plantago lanceolata,

Scabiosa columbaria, and

Thymus pulegioides. Their compact aggregation on the left side of the ordination reflects floristic stability and relative homogeneity of weakly fertilized grasslands.

As manure application increased (20–30 t ha−1; T3_O, T4_O) or moderate mineral fertilization was applied (N50P25K25; T2_M), the plant communities shifted toward the central region of ordination. Here, the T. flavescens–F. rubra and T. flavescens–F. pratensis–C.a pseudophrygia subtypes were distinguished, indicating intermediate stages between oligotrophic and eutrophic grasslands, respectively. Floristic composition gradually became more complex and competitive, with higher participation of species such as T. flavescens, Pimpinella major, Crepis biennis, Colchicum autumnale, and Hypericum maculatum. This shift reflects increased nutrient availability and a gradual change in the competitive balance in favor of mesotrophic species. The treatments with intensive mineral fertilization (N100P50K50 and N150P75K75; T3_M and T4_M) were positioned on the positive side of Axis 1, forming well-defined groups corresponding to A. capillaris–T. flavescens and A. capillaris–Festuca pratensis–C. pseudophrygia communities. These grasslands are characterized by the dominance of nitrophilous and highly competitive species, such as A. capillaris, F. pratensis, T. flavescens, C. pseudophrygia, Veronica chamaedrys, and Rumex acetosa. Their distinct separation reflects the simplification and homogenization of the vegetation structure typical of intensively fertilized ecosystems, where oligotrophic species gradually disappear. Axis 2 (r = 0.057) captured secondary variation primarily associated with differences between purely organic and mineral fertilization. Manure-treated variants (T2_O, T3_O, and T4_O) tended to cluster in the upper part of the ordination, whereas mineral-fertilized variants (T2_M, T3_M, and T4_M) were located lower along the axis. This pattern reflects the subtle influence of fertilizer type on floristic composition, with slightly more heterogeneous communities under organic fertilization than under mineral fertilization.

Overall, the ordination revealed a coherent floristic gradient from oligotrophic F. rubra-dominated grasslands to eutrophic A. capillaris-dominated swards with increasing fertilization intensity. This spatial differentiation confirms the decisive role of long-term fertilization in shaping mountain grassland community structure.

The correlation coefficients illustrated how each fertilization treatment contributed to the separation of grassland communities along the PCoA axes, reflecting the trophic gradient generated by different levels of organic and mineral inputs (

Table 5). The application of 10 t ha

−1 of manure (O_10t) showed a weak, negative, and non-significant correlation with Axis 1, indicating that low organic inputs did not strongly influence the primary gradient of the ordination. However, the positive and significant correlation with Axis 2 suggests that this low-input treatment produces detectable floristic changes along the secondary ecological gradient, associated with the emergence of slightly mesotrophic species in the second year. For 20 t ha

−1 of manure (O_20t), the correlation with Axis 1 remained non-significant, whereas the positive and significant correlation with Axis 2 became stronger than that in the previous variant. This pattern indicates that medium organic fertilization more clearly influences the secondary community structure, reinforcing the transition toward mesotrophic grassland assemblages. Under the highest level of organic fertilization, 30 t ha

−1 of manure (O_30t), a marked shift occurred, and the correlation with Axis 1 became positive and significant. This demonstrates a clear association between high organic inputs and the primary trophic gradient, where communities with higher productivity and a more uniform floristic composition are separated. The correlation with Axis 2 remained non-significant, indicating that the main ecological response was captured predominantly by Axis 1. For moderate mineral fertilization, N50P25K25 (M_50N), the pattern resembled that of moderate organic inputs: a non-significant negative correlation with Axis 1 and a positive, significant correlation with Axis 2. This indicates that moderate mineral inputs influence secondary floristic differences without strongly affecting the main trophic gradients.

In the case of high mineral fertilization, N100P50K50 (M_100N), the correlation with Axis 1 was positive, significant, and the highest among all treatments. This confirms the strong effect of intensive mineral fertilization in shifting plant communities toward the eutrophic end of the primary gradient, which is consistent with the dominance of competitive, nutrient-responsive species. The correlation with Axis 2 was not significant, suggesting that most of the ecological responses to high mineral fertilization were embedded in Axis 1. Overall, the table demonstrates a progressive increase in positive correlations with Axis 1 as fertilization intensity increases, particularly with mineral inputs. This pattern reflects the transition from oligotrophic F. rubra grasslands to mesotrophic and eutrophic communities dominated by A. capillaris and F. pratensis. In contrast, Axis 2 captures more subtle floristic responses associated with low and moderate inputs, highlighting the secondary patterns of variation within the grassland system.

The MRPP results (

Table 6) clearly show that both organic and mineral fertilization resulted in significant shifts in the floristic composition of mountain grasslands. All pairwise comparisons between treatments were statistically significant (

p < 0.01), indicating that each fertilization level generated a distinct plant community. The consistently negative T values combined with positive A coefficients reflect a strong separation among treatments and high within-group homogeneity. The most pronounced differences were observed between the control (T1) and all fertilized variants, both organic (T2_O, T3_O, T4_O) and mineral (T2_M, T3_M, T4_M). The highly negative T statistics (between −7.21 and −7.33) and high A values (0.55–0.73) reveal a major ecological divergence between the oligotrophic

F. rubra grasslands and fertilized plots characterized by increased productivity and altered floristic structure. This pattern is fully consistent with the PCoA ordination, where the control plots occupy the negative side of Axis 1, clearly separated from all fertilized treatments. Differences among organic fertilization levels (T2_O vs. T3_O; T2_O vs. T4_O; T3_O vs. T4_O) were also significant, indicating that increasing manure inputs drive gradual but well-defined floristic transitions. In the PCoA diagram, organic treatments followed a coherent spatial sequence, from positions closer to the control (T2_O) to progressively more positive values on Axis 1 (T3_O and T4_O), matching the increasing trophic status.

Mineral treatments (T2_M, T3_M, T4_M) were also distinct from one another, with all pairwise comparisons showing significant differences. High A values (0.65–0.75) indicate strong internal consistency and clear separation among the mineral input levels. In the ordination space, mineral treatments clustered on the positive side of Axis 1 and were arranged in an order reflecting the increasing intensity of mineral fertilization, from T2_M to T4_M. Comparisons between organic and mineral treatments (e.g., T2_O vs. T2_M; T3_O vs. T3_M; T4_O vs. T4_M) were also statistically significant, demonstrating that the source of nutrients (organic vs. mineral) affects floristic composition differently, even when nutrient levels are comparable. In the PCoA, organic treatments tended to occupy intermediate positions, whereas mineral treatments extended further along the eutrophic end of Axis 1. Even in cases where cluster analysis grouped organic and mineral variants together, such as T2_O and T2_M in Cluster 2, the MRPP test revealed significant floristic differences between them (T = −3.257, p = 0.0089). This indicates that, despite forming a similar vegetation subtype, the two treatments maintain distinct community signatures shaped by the source and release dynamics of nutrients.

Overall, the MRPP analysis confirmed the existence of a well-defined trophic gradient, ranging from oligotrophic control grasslands to increasingly productive mesotrophic and eutrophic communities shaped by rising levels of organic and mineral fertilization. This gradient aligned perfectly with the structure revealed by PCoA, demonstrating the consistency and robustness of the results.

3.3. The Response of Plant Species to Organic and Mineral Inputs

To identify which species drive the ordination patterns, we analyzed species–axis correlations (

Table 7), which revealed a well-defined trophic gradient represented by Axis 1. Positive

r values were associated with mesotrophic and nitrophilic species favored by increased nutrient availability. These included

A. capillaris (r = 0.741,

p < 0.001),

F. pratensis (r = 0.894,

p < 0.001),

P. trivialis (r = 0.897,

p < 0.001), and

T. flavescens (r = 0.515,

p < 0.01). Such species typically dominate grassland communities subjected to mineral fertilization or higher organic inputs and reflect a shift toward more productive, nutrient-enriched conditions. Conversely, strongly negative correlations on Axis 1 characterize oligotrophic and stress-tolerant species typical of unfertilized or low-input organic treatments. Among these,

F. rubra (r = −0.921,

p < 0.001),

C. pallescens (r = −0.744,

p < 0.001),

L. multiflora (r = −0.833,

p < 0.001), and

Lotus corniculatus (r = −0.850,

p < 0.001) are indicative of HNV grasslands, where low soil fertility supports a diverse and stable floristic structure. Axis 2 captures secondary ecological variation related to the type of fertilization. Significant positive correlations were recorded for species such as

T. flavescens (r = 0.759,

p < 0.001),

V. chamaedrys (r = 0.668,

p < 0.01),

P. major (r = 0.734,

p < 0.001), and

C. autumnale (r = 0.631,

p < 0.001), suggesting a preference for fertilization regimes associated with increased nutrient availability. In contrast, moderately negative correlations (e.g.,

Trifolium pratense,

Trifolium repens,

C. pseudophrygia,

Rhinanthus minor) indicate species that are more closely associated with lower trophic conditions or organic inputs.

Overall, Axis 1 reflects the gradient of fertilization intensity, showing a floristic transition from oligotrophic F. rubra grasslands to more productive, nutrient-responsive communities. Axis 2 differentiates secondary patterns related to the type and level of nutrient input, which is in agreement with the patterns observed in the PCoA diagram.

The distribution of species along the trophic gradient closely aligned with the trends identified through PCoA, showing a consistent association of mesotrophic species with moderate and high fertilization levels and a clear distinction of oligotrophic species in the control plots. These findings provide a coherent ecological framework for Indicator Species Analysis (ISA), where the diagnostic value of individual species is assessed in relation to the identified vegetation groups.

3.4. Indicator Species Analysis to the Gradient of Applied Inputs Organo and Mineral

Based on the trophic gradient identified by the ordination analyses, Indicator Species Analysis (ISA) was applied using the seven fertilization treatments as grouping factors (T1–control; T2_O–10 t ha

−1 manure; T3_O–20 t ha

−1 manure; T4_O–30 t ha

−1 manure; T2_M–N50P25K25; T3_M–N100P50K50; T4_M–N150P75K75). The results (

Table 8) revealed well-defined diagnostic species for each treatment, confirming the ecological differentiation generated by the increase in nutrient inputs. Low-input treatments—T2_O (10 t ha

−1 manure) and T2_M (N50P25K25)—were associated with early mesotrophic indicator species, particularly

Trifolium repens and

Trifolium pratense (

p < 0.05). In this study, these species indicate moderate nutrient enrichment because they reached significant indicator values under low-input treatments while overall species richness, evenness, and community structure remained close to those of the unfertilized control. Their occurrence therefore reflects a moderate increase in nutrient availability without disrupting the structural balance and characteristic floristic composition of HNV grasslands. Control plots (T1_O + T1_M; Group 1) showed the highest number of significant indicator species (

p < 0.01), including

Festuca rubra,

B. media,

L. multiflora,

A. vulneraria,

L. corniculatus,

P. media,

P. vulgaris, and

T. pulegioides. These species typify oligotrophic HNV grasslands and reflect the stable, low-fertility conditions of the unfertilized variants.

Low-input treatments—T2_O (10 t ha−1 manure; Group 2) and T2_M (N50P25K25; Group 5)—were associated with early mesotrophic indicator species, particularly T. repens and T. pratense (p < 0.05). Their occurrence indicates moderate nutrient enrichment while maintaining structural balance and preserving the HNV character. Medium-input treatments, T3_O (20 t ha−1 manure; Group 3) and T3_M (N100P50K50; Group 6), displayed indicator species characteristics of transitional mesotrophic grasslands, such as Vicia cracca and C. pseudophrygia (p < 0.01). These species signal a shift toward more productive communities with increasing competitive interactions and a reduced representation of conservative oligotrophic taxa. High-input organic fertilization (T4_O–30 t ha−1 manure; Group 4) was associated with productive species such as F. pratensis and P. major (p < 0.05), indicating advanced mesotrophic–eutrophic conditions and a strong response to high manure inputs. High-input mineral fertilization (T4_M–N150P75K75; Group 7) showed strong affinities with nitrophilous and eutrophic species, including A. capillaris, P. trivialis, H. maculatum, and V. chamaedrys (p < 0.01). These taxa represent intensively fertilized, low-diversity communities that are typical of strongly eutrophicated mountain grasslands.

Overall, ISA revealed a coherent ecological progression from oligotrophic Festuca rubra-dominated communities with zero input (T1) to mesotrophic assemblages under moderate organic or mineral fertilization (T2 and T3), and finally to eutrophic Agrostis capillaris-type communities under high mineral fertilization (T4_M).

Although ISA distinguished seven treatment-based groups and cluster analysis identified six vegetation types, both approaches consistently reflected the same ecological gradient. The apparent discrepancy arises because ISA groups are defined strictly by fertilization treatments, whereas the cluster analysis groups vegetation types based on floristic similarity. For example, T2_O and T2_M formed two ISA groups owing to their different fertilizer sources, yet they belonged to the same vegetation subtype (Cluster 2), highlighting their similar floristic response despite different nutrient origins. These findings match the spatial patterns identified by PCoA and the group differences detected by MRPP, demonstrating strong analytical consistency across methods and confirming the robustness of fertilization-induced trophic gradients.

3.5. The Influence of Organic and Mineral Fertilizer on Plant Diversity

The analysis of diversity parameters (

Table 9) indicated consistent and statistically significant effects of fertilization intensity on grassland diversity. ANOVA revealed significant differences among the treatments in terms of species richness (F = 72.43,

p < 0.001), Shannon diversity (F = 14.14,

p < 0.001), and Simpson index (F = 5.60,

p = 0.004), whereas evenness did not differ significantly (F = 1.01,

p = 0.401). These results indicate that fertilization primarily affects the number of species and overall community complexity, whereas the distribution of abundance among species remains relatively stable. The control treatment (T1–combined organic and mineral) displayed the highest species richness (S = 33.63 ± 1.30), Shannon diversity (H′ = 2.91 ± 0.06), and evenness (E = 0.827 ± 0.012). These values reflect the oligotrophic and structurally stable characteristics of HNV grasslands, a pattern further supported by the high Simpson index (D = 0.9245 ± 0.0054).

Under low-input organic fertilization (T2 organic), diversity remained relatively high (H′ = 2.78 ± 0.03), although species richness declined moderately (S = 31.50 ± 2.08). This indicates that moderate nutrient input may stimulate certain mesotrophic species without substantially altering the overall community structure. Medium organic fertilization (T3 organic) caused a marked reduction in species number (S = 24.00 ± 0.82), but evenness remained high (E = 0.860 ± 0.021), suggesting reorganization around a smaller set of competitive species. High-input organic fertilization (T4 organic) led to a further decline in diversity (H′ = 2.66 ± 0.02), although the evenness values continued to indicate relatively balanced species distributions.

In the mineral fertilization experiment, the decline in diversity was more pronounced. Under low-input mineral fertilization (T2), species richness dropped to 27.00 ± 0.82, and the Shannon index decreased to 2.64 ± 0.06. Medium and high mineral inputs (T3 and T4) produced substantial reductions across all indices, with the highest intensity treatment (T4) showing the lowest diversity (H′ = 2.29 ± 0.07), evenness (E = 0.750 ± 0.017), and Simpson index (D = 0.8544 ± 0.0115). These values reflect communities increasingly dominated by a small number of nitrophilous species typical of strongly eutrophic grasslands.

Overall, the results demonstrate that fertilization significantly alters grassland community composition, with mineral inputs producing much stronger shifts than organic fertilization. The control treatment consistently exhibited the highest diversity, highlighting the sensitivity of HNV grasslands to nutrient enrichment and confirming the ecological gradient detected by multivariate analyses.

The results clearly demonstrate the strong influence of fertilization type and intensity on the structure and diversity of mountain grasslands, revealing a consistent ecological transition from oligotrophic to mesotrophic and ultimately to eutrophic community types. All analytical approaches—MRPP, PCoA, ISA, and diversity indices—converged in depicting the same trophic gradient induced by increasing nutrient inputs. This coherence across multiple methods provides a solid quantitative basis for the ecological interpretation developed in the Discussion.