Transcriptome Analysis of Germinated Maize Embryos Reveals Common Gene Responses to Multiple Abiotic Stresses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Stress Treatments

2.2. Evaluation of Seed Physiological Indicators

2.3. Transcriptome Sequencing and Gene Expression Analysis

2.4. Hierarchical Clustering and Functional Annotation Enrichment Analysis

2.5. Quantitative RT-PCR Validation

3. Results

3.1. The Effect of Temperature, Salinity, and Moisture on Maize Seed Germination

3.2. Transcriptome of Germinated Embryos in Response to Temperature, Salinity, and Drought Stresses

3.3. Differentially Expressed Genes Under High-Temperature, Low-Temperature, Salinity and Drought Stresses Compared to Standard Germination

3.4. Identification of Common srDEGs in Response to Multiple Abiotic Stresses

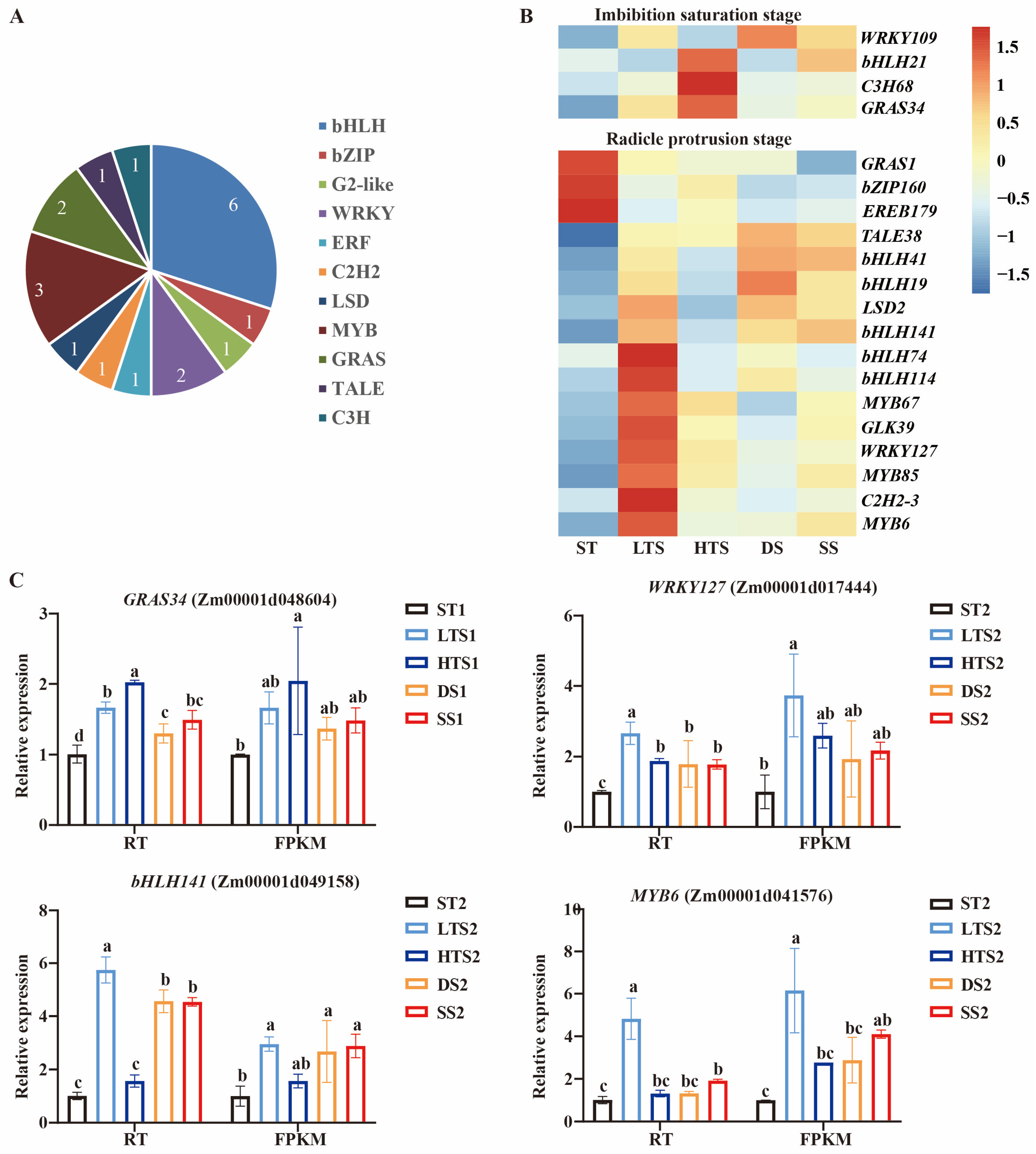

3.5. Common Stress-Responsive Transcription Factors During Gemination

4. Discussion

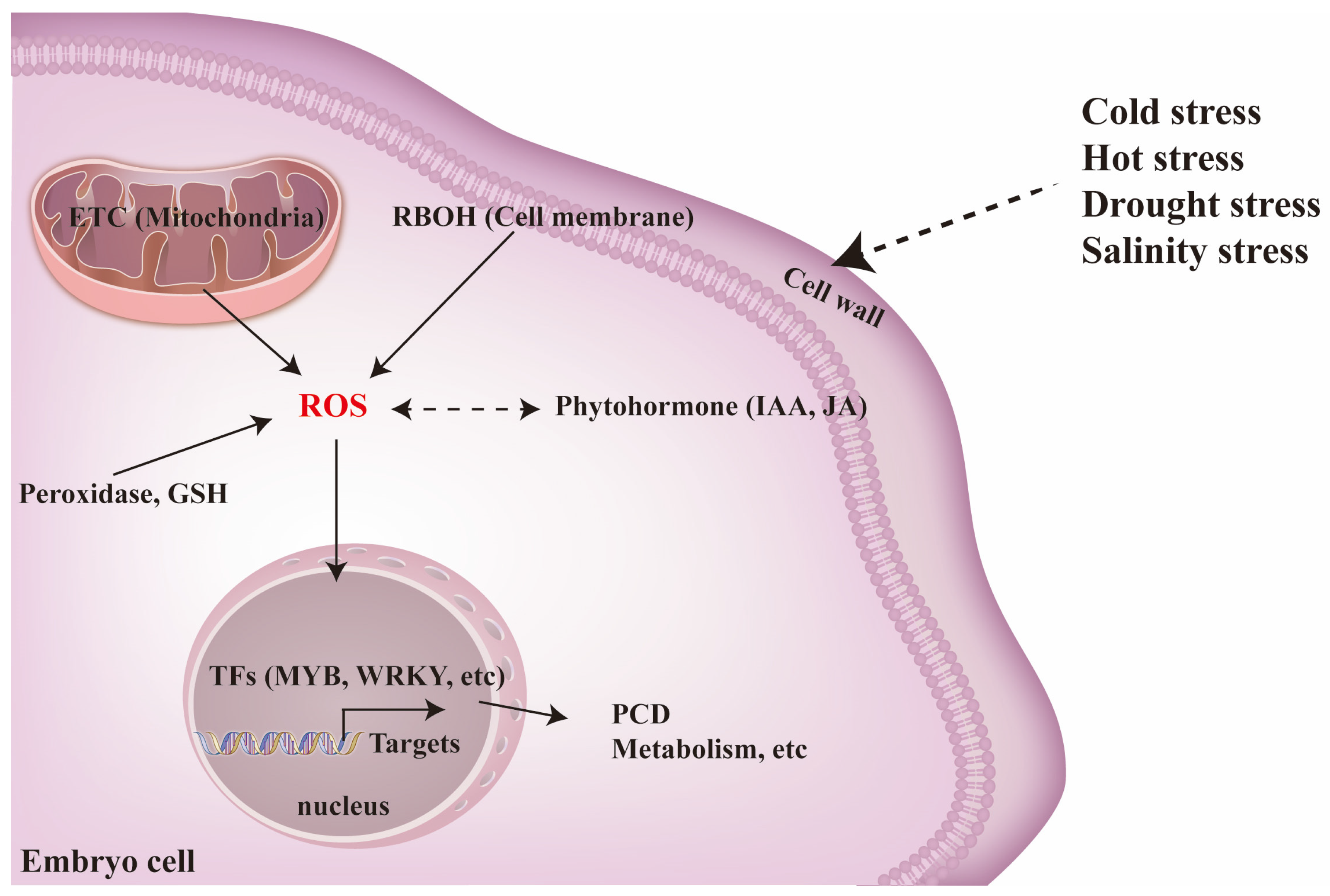

4.1. ROS Signaling Plays a Vitol Role in Multiple Stress Tolerance During Germination

4.2. Potential Transcription Factors Regulating Multiple Stress Tolerance in Germinating Maize Seeds

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, Q.; Wang, J.; Sun, B. Advances on seed vigor physiological and genetic mechanisms. Agric. Sci. China 2007, 6, 1060–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonogaki, H.; Bassel, G.W.; Bewley, J.D. Germination—Still a mystery. Plant Sci. 2010, 179, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, B.; Kashtoh, H.; Lama Tamang, T.; Bhattacharyya, P.N.; Mohanta, Y.K.; Baek, K.H. Abiotic Stress in Rice: Visiting the Physiological Response and Its Tolerance Mechanisms. Plants 2023, 12, 3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, S. Heat and chilling induced disruption of redox homeostasis and its regulation by hydrogen peroxide in germinating rice seeds (Oryza sativa L., Cultivar Ratna). Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2013, 19, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Qiu, J.; Soufan, W.; El Sabagh, A. Synergistic effects of melatonin and glycine betaine on seed germination, seedling growth, and biochemical attributes of maize under salinity stress. Physiol. Plant 2024, 176, e14514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Q.; Sami, A.; Haider, M.Z.; Ashfaq, M.; Javed, M.A. Antioxidant production promotes defense mechanism and different gene expression level in Zea mays under abiotic stress. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waadt, R.; Seller, C.A.; Hsu, P.K.; Takahashi, Y.; Munemasa, S.; Schroeder, J.I. Plant hormone regulation of abiotic stress responses. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 680–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Ni, L.; Liu, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, A.; Tan, M.; Jiang, M. ZmABA2, an interacting protein of ZmMPK5, is involved in abscisic acid biosynthesis and functions. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2016, 14, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Ying, S.; Zhang, D.F.; Shi, Y.S.; Song, Y.C.; Wang, T.Y.; Li, Y. A maize stress-responsive NAC transcription factor, ZmSNAC1, confers enhanced tolerance to dehydration in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 2012, 31, 1701–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Yu, L.; Han, R.; Li, Z.; Liu, H. ZmNAC55, a maize stress-responsive NAC transcription factor, confers drought resistance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 105, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.J.; Song, S.I.; Kim, Y.S.; Jang, H.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, M.; Kim, Y.K.; Nahm, B.H.; Kim, J.K. Arabidopsis CBF3/DREB1A and ABF3 in transgenic rice increased tolerance to abiotic stress without stunting growth. Plant Physiol. 2005, 138, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Liu, X.; Yu, S.; Liu, J.; Jiang, L.; Lu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, S. The maize ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter ZmMRPA6 confers cold and salt stress tolerance in plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2023, 43, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, S.; Sun, M.; Wei, H.; Muhammad, F.; Liu, L.; Shi, G.; Gao, Y. Mn-doped cerium dioxide nanozyme mediates ROS homeostasis and hormone metabolic network to promote wheat germination under low-temperature conditions. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2025, 12, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Fan, X.; Wang, C.; Jiao, P.; Jiang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Guan, S.; Liu, S. Overexpression of ZmDHN15 Enhances Cold Tolerance in Yeast and Arabidopsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.T.; Zheng, L.; Ma, X.J.; Yu, T.F.; Gao, X.; Hou, Z.H.; Liu, Y.W.; Cao, X.Y.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Y.B.; et al. An ABF5b-HsfA2h/HsfC2a-NCED2b/POD4/HSP26 module integrates multiple signaling pathway to modulate heat stress tolerance in wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 17, 4735–4751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.C.; Zhang, H.N.; Li, G.L.; Liu, Z.H.; Guo, X.L. Expression of maize heat shock transcription factor gene ZmHsf06 enhances the thermotolerance and drought-stress tolerance of transgenic Arabidopsis. Funct. Plant Biol. 2015, 42, 1080–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Ye, Y. Maize Class C Heat Shock Factor ZmHSF21 Improves the High Temperature Tolerance of Transgenic Arabidopsis. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.C.; Niu, C.Y.; Yang, C.R.; Jinn, T.L. The heat-stress factor HSFA6b connects ABA signaling and ABA-mediated heat responses. Plant Physiol. 2016, 172, 1182–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Yin, Z.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, M.; Guo, X.; Ye, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, Z. OsASR5 enhances drought tolerance through a stomatal closure pathway associated with ABA and H2O2 signalling in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017, 15, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, W.; Hang, X.; Chen, S.; Xiling, W.; Lei, W. Rice CIRCADIAN CLOCK ASSOCIATED 1 transcriptionally regulates ABA signaling to confer multiple abiotic stress tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2022, 190, 1057–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, L. Overexpression of TaWRKY53 enhances drought tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 148, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, J.N.; Hou, Z.H.; Zheng, L.; Zhao Shi, X.U. Genome-wide analysis of DEAD-box RNA helicase family in wheat (Triticum aestivum) and functional identification of TaDEAD-box57 in abiotic stress responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 797276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mito, T.; Seki, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Ohme-Takagi, M.; Matsui, K. Generation of chimeric repressors that confer salt tolerance in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2011, 9, 736–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, A.; Li, S.; Li, W.; Hao, Q.; Jiang, X. RhNAC31, a novel rose NAC transcription factor, enhances tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses in Arabidopsis. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2019, 41, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.C.; Mei, C.; Liang, S.; Yu, Y.T.; Lu, K.; Wu, Z.; Wang, X.F.; Zhang, D.P. Crucial roles of the pentatricopeptide repeat protein SOAR1 in Arabidopsis response to drought, salt and cold stresses. Plant Mol. Biol. 2015, 88, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hou, C.; Zheng, K.; Li, Q.; Chen, S.; Wang, S. Overexpression of ERF96, a small ethylene response factor gene enhances salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. Biol. Plant. 2017, 61, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorillo, A.; Manai, M.; Visconti, S.; Camoni, L. The Salt Tolerance–Related Protein (STRP) Is a Positive Regulator of the Response to Salt Stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plants 2023, 12, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, D.J.; Moon, J.C.; Hwang, S.G.; Jang, C.S. Molecular characterization of two small heat shock protein genes in rice: Their expression patterns, localizations, networks, and heterogeneous overexpressions. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013, 40, 6709–6720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, G.; Kang, H. Rice OsRH58, a chloroplast DEAD-box RNA helicase, improves salt or drought stress tolerance in Arabidopsis by affecting chloroplast translation. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, N.; Tarnawa, Á.; Balla, I.; Omar, S.; Abd Ghani, R.; Jolánkai, M.; Kende, Z. Combination effect of temperature and salinity stress on germination of different maize (Zea mays L.) varieties. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Cao, Y.; Lv, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y. Integrating physiological, metabolome and transcriptome revealed the response of maize seeds to combined cold and high soil moisture stresses. Physiol. Plant 2025, 177, e70096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Chen, D.; Lv, Y.; Xu, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L. Thriving in adversity: Understanding how maize seeds respond to the challenge of combined cold and high humidity stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 219, 109445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, J.; Gong, Z.; Zhu, J. Abiotic stress responses in plants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azad, M.; Tohidfar, M.; Ghanbari, M.S.R.; Mehralian, M.; Esmaeilzadeh-Salestani, K. Identification of responsive genes to multiple abiotic stresses in rice (Oryza sativa): A meta-analysis of transcriptomics data. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, R.; Peláez-Vico, M.Á.; Shostak, B.; Nguyen, T.T.; Pascual, L.S.; Ogden, A.M.; Lyu, Z.; Zandalinas, S.I.; Joshi, T.; Fritschi, F.B.; et al. The effects of multifactorial stress combination on rice and maize. Plant Physiol. 2024, 194, 1358–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Liu, J.; Ye, T.; Li, X.; Tu, H.; Ye, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, L. Stress-induced nuclear translocation of ONAC023 improves drought and heat tolerance through multiple processes in rice. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, B.; Kaur, I.; Dhingra, Y.; Saxena, V.; Krishna, G.K.; Kumar, R.; Chinnusamy, V.; Agarwal, M.; Katiyar-Agarwal, S. Tetraspanin 5 orchestrates resilience to salt stress through the regulation of ion and reactive oxygen species homeostasis in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, W.; Qi, L.; Wang, A.; Ye, X.; Du, L.; Liang, H.; Xin, Z.; Zhang, Z. The ERF transcription factor TaERF3 promotes tolerance to salt and drought stresses in wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2014, 12, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, L.; Sun, W.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Sun, D.; Lin, H.; Fan, J.; Zhou, Y.; et al. The transcription factor ZmMYBR24 gene is involved in a variety of abiotic stresses in maize (Zea mays L.). Plants 2025, 14, 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International seed testing association (ISTA). International Rules for Seed Testing; ISTA: Zurich, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, S.; Pyl, P.T.; Huber, W. HTSeq—A Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, N.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, F.; Han, D.; Zhang, H.; Yang, T.; Li, L.; Chen, Q.; Li, L.; et al. The Hub Gene ZmbZIP29 Mediated Early Starch Degradation Within Embryo Determines Seed Germination Speed in Maize; China Agricultural University: Beijing, China, 2025; submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, R.; Shimodaira, H. Pvclust: An R package for assessing the uncertainty in hierarchical clustering. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 1540–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Xi, M.; Liu, T.; Wu, X.; Ju, L.; Wang, D. The central role of transcription factors in bridging biotic and abiotic stress responses for plants’ resilience. New Crops 2024, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R.; Zandalinas, S.I.; Fichman, Y.; Van Breusegem, F. Reactive oxygen species signalling in plant stress responses. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; He, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z. Advances in the molecular regulation of seed germination in plants. Seed Biol. 2024, 3, e006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly, C.; Merendino, L. Oxidative signalling in seed germination and early seedling growth: An emerging role for ROS trafficking and inter-organelle communication. Biochem. J. 2021, 478, 1977–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, V.; Majeed, U.; Kang, H.; Andrabi, K.I.; John, R. Abiotic stress: Interplay between ROS, hormones and MAPKs. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2017, 137, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, F.K.; Rivero, R.M.; Blumwald, E.; Mittler, R. Reactive oxygen species, abiotic stress and stress combination. Plant J. 2017, 90, 856–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandalinas, S.I.; Fichman, Y.; Devireddy, A.R.; Sengupta, S.; Azad, R.K.; Mittler, R. Systemic signaling during abiotic stress combination in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 13810–13820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liu, W.C.; Han, C.; Wang, S.; Bai, M.Y.; Song, C.P. Reactive oxygen species: Multidimensional regulators of plant adaptation to abiotic stress and development. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 330–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Dai, Y.; Zheng, C.; Yang, Y.; Chen, W.; Wang, Q.; Chandrasekaran, U.; Du, J.; Liu, W.; Shu, K. The ABI4-RbohD/VTC2 regulatory module promotes reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation to decrease seed germination under salinity stress. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 950–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, Y.; Hu, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Tao, J.; Zhao, D. PlPOD45 positively regulates high-temperature tolerance of herbaceous peony by scavenging reactive oxygen species. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2024, 30, 1581–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhamdi, A.; Van Breusegem, F. Reactive oxygen species in plant development. Development 2018, 145, dev164376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lariguet, P.; Ranocha, P.; De Meyer, M.; Barbier, O.; Penel, C.; Dunand, C. Identification of a hydrogen peroxide signalling pathway in the control of light-dependent germination in Arabidopsis. Planta 2013, 238, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Chang, Y.L.; Wu, H.T.; Shalmani, A.; Liu, W.T.; Li, W.Q.; Xu, J.W.; Chen, K.M. OsRbohB-mediated ROS production plays a crucial role in drought stress tolerance of rice. Plant Cell Rep. 2020, 39, 1767–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Niu, H.; Xin, D.; Long, Y.; Wang, G.; Liu, Z.; Li, G.; Zhang, F.; Qi, M.; Ye, Y.; et al. OsIAA18, an Aux/IAA transcription factor gene, is involved in salt and drought tolerance in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 738660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erpen, L.; Devi, H.S.; Grosser, J.W.; Dutt, M. Potential use of the DREB/ERF, MYB, NAC and WRKY transcription factors to improve abiotic and biotic stress in transgenic plants. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2017, 132, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baoxiang, W.; Zhiguang, S.; Yan, L.; Bo, X.; Jingfang, L.; Ming, C.; Yungao, X.; Bo, Y.; Jian, L.; Jinbo, L.; et al. A pervasive phosphorylation cascade modulation of plant transcription factors in response to abiotic stress. Planta 2023, 258, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.J.; Yan, J.Y.; Li, C.X.; Li, G.X.; Wu, Y.R.; Zheng, S.J. Transcription factor WRKY46 modulates the development of Arabidopsis lateral roots in osmotic/salt stress conditions via regulation of ABA signaling and auxin homeostasis. Plant J. 2015, 84, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Ma, C.; Wang, Z.; Shi, X.; Duan, W.; Fu, X.; Liu, J.; Guo, C.; Xiao, K. Transcription factor gene TaWRKY76 confers plants improved drought and salt tolerance through modulating stress defensive-associated processes in Triticum aestivum L. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 216, 109147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.; Basit, F.; Tanwir, K.; Zhu, X.; Hu, J.; Guan, Y.; Hu, W.; Sheteiwy, M.S.; Yang, H.; El-Keblawy, A.; et al. Exogenously applied sodium nitroprusside alleviates nickel toxicity in maize by regulating antioxidant activities and defense-related gene expression. Physiol. Plant 2023, 175, e13985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasani, E.; DalCorso, G.; Costa, A.; Zenoni, S.; Furini, A. The Arabidopsis thaliana transcription factor MYB59 regulates calcium signalling during plant growth and stress response. Plant Mol. Biol. 2019, 99, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Seo, P.J. Ca2+ talyzing initial responses to environmental stresses. Trends Plant Sci. 2021, 26, 849–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Machorro, A.L. Homodimeric and heterodimeric interactions among vertebrate basic Helix-Loop-Helix transcription factors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zheng, N.; Cheng, Y.; Yu, F.; Li, L.; Chen, Q.; Wang, J.; Gu, R.; Du, X. Transcriptome Analysis of Germinated Maize Embryos Reveals Common Gene Responses to Multiple Abiotic Stresses. Agronomy 2026, 16, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010040

Zheng N, Cheng Y, Yu F, Li L, Chen Q, Wang J, Gu R, Du X. Transcriptome Analysis of Germinated Maize Embryos Reveals Common Gene Responses to Multiple Abiotic Stresses. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010040

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Nannan, Yong Cheng, Fenghao Yu, Li Li, Quanquan Chen, Jianhua Wang, Riliang Gu, and Xuemei Du. 2026. "Transcriptome Analysis of Germinated Maize Embryos Reveals Common Gene Responses to Multiple Abiotic Stresses" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010040

APA StyleZheng, N., Cheng, Y., Yu, F., Li, L., Chen, Q., Wang, J., Gu, R., & Du, X. (2026). Transcriptome Analysis of Germinated Maize Embryos Reveals Common Gene Responses to Multiple Abiotic Stresses. Agronomy, 16(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010040