1. Introduction

As a vital economic crop, cotton yield directly influences farmers’ income and the overall performance of the agricultural economy [

1]. To ensure stable and high yields, topping operations during the vigorous growth period (June to July) are essential. This process effectively enhances yield by removing the apical growth point, weakening apical dominance, and redirecting nutrients toward boll development [

2]. Traditional manual topping is labor-intensive, inefficient, and heavily dependent on farmers’ visual experience, which limits operational accuracy. With the rapid advancement of agricultural mechanization and intelligent equipment, the adoption of cotton topping machines has significantly improved operational efficiency and reduced labor costs [

3]. As a key sensing component in mechanized operations, accurate apical bud recognition via computer vision forms the foundation for automated topping.

With the continuous evolution of the YOLO series [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8], object detection techniques have become increasingly mature and widely applied in agricultural scenarios. Xuening Zhang et al. [

9] employed YOLOv8 as the baseline model, replacing the C2f module with a cross-level partial network and partial convolution (CSPPC) module, and optimized the loss function using Inner CIoU, which introduces auxiliary inner bounding boxes to emphasize overlap consistency within predicted and ground-truth regions, thereby improving localization accuracy for small objects, achieving 97% accuracy on a self-constructed dataset. Yufei Xie et al. [

10] formulated cotton apical bud detection as a small-object detection problem and proposed a leaf morphology region-of-interest (ROI) generation network based on YOLOv11n, achieving 96.7% accuracy by constraining the search range. Similarly, Meng Li et al. [

11] developed CMD-YOLO to improve the accuracy of small-object detection for cherry ripeness, reducing model complexity through structure simplification and enhanced feature fusion. Compared to the YOLOv12 baseline, it achieved a 5.3% improvement in accuracy and a 73.1% reduction in parameters. For potato bud detection, Qiang Zhao et al. [

12] improved YOLOv5s performance by introducing an additional small-object detection layer and attention mechanism, enabling high-precision detection of potato “buds.” As another state-of-the-art framework, Faster R-CNN [

13] has also been widely applied in agriculture. Andrew Magdy et al. [

14] proposed a lightweight Faster R-CNN-based model tailored for agricultural remote sensing, performing high-resolution detection of crop distribution, land use, and pest-infected regions. By optimizing RoI pooling and region proposal processes, both inference speed and detection accuracy were improved. Although numerous models based on YOLO and Faster R-CNN have been developed for agricultural object detection [

15], most improvements primarily focus on architectural optimization to enhance feature extraction and convergence speed. Consequently, achieving higher accuracy and robustness often demands extensive datasets, resulting in substantial annotation costs and computational overhead.

Despite the progress of YOLO-based methods for apical bud detection, their deployment in real-world field environments remains challenging. The field environment is inherently complex: apical buds are frequently occluded by upper leaves, illumination varies drastically across time and climate, and noise arises from dust, pollution, and cluttered backgrounds. These factors collectively diminish the visual saliency of apical buds, complicating feature extraction and target localization. Moreover, apical buds exhibit typical small-object characteristics—small size, variable scale, and high similarity to surrounding tissues—causing mainstream one-stage detectors to miss or misidentify targets under multi-occlusion and weak-saliency conditions. To address these challenges, this paper proposes an indirect apical bud localization approach based on cotton top-leaf segmentation. The proposed method leverages the morphological relationship between the apical bud and top leaves, as illustrated in

Figure 1, effectively alleviating false and missed detections observed in direct detection tasks. Cotton, being an indeterminate plant, exhibits a reflective leaf arrangement pattern in which top leaves radiate around the terminal bud, typically located near the intersection of extended petiole lines [

16]. This spatial configuration provides a novel means for locating the apical bud. Additionally, since top leaves have larger areas and more distinct visual features, they can be segmented more accurately. Hence, top-leaf segmentation becomes a crucial step.

Segmentation techniques can generally be categorized as single-stage, two-stage, or multi-stage approaches. Single-stage models—such as YOLACT [

17], YOLACT++ [

18], SOLO [

19], and the YOLO-Seg series—unify detection and segmentation into an end-to-end framework, bypassing the conventional “detect-then-extract” process by directly predicting instance masks at the pixel level. Two-stage models, such as Mask R-CNN [

20], first generate region proposals before mask prediction. However, existing segmentation models still require extensive annotations and training resources. In contrast to detection tasks, segmentation labels consist of detailed polygon contours rather than simple bounding boxes. In April 2023, Meta AI introduced the Segment Anything Model (SAM) [

21], establishing a new segmentation paradigm. SAM, built upon a Vision Transformer (ViT) encoder, uses point, box, and mask prompts as inputs to achieve interactive zero-shot segmentation. Owing to its strong generalization, SAM has been widely adopted in medical image analysis [

22] and remote sensing segmentation [

23]. Nevertheless, it experiences significant performance degradation in agricultural applications characterized by long petioles, fine structures, severe occlusion, and weak texture, and remains sensitive to prompt quality and scale [

24]. For agricultural automation, an interactive segmentation paradigm is impractical—an end-to-end segmentation framework with automatic prompting is therefore preferred.

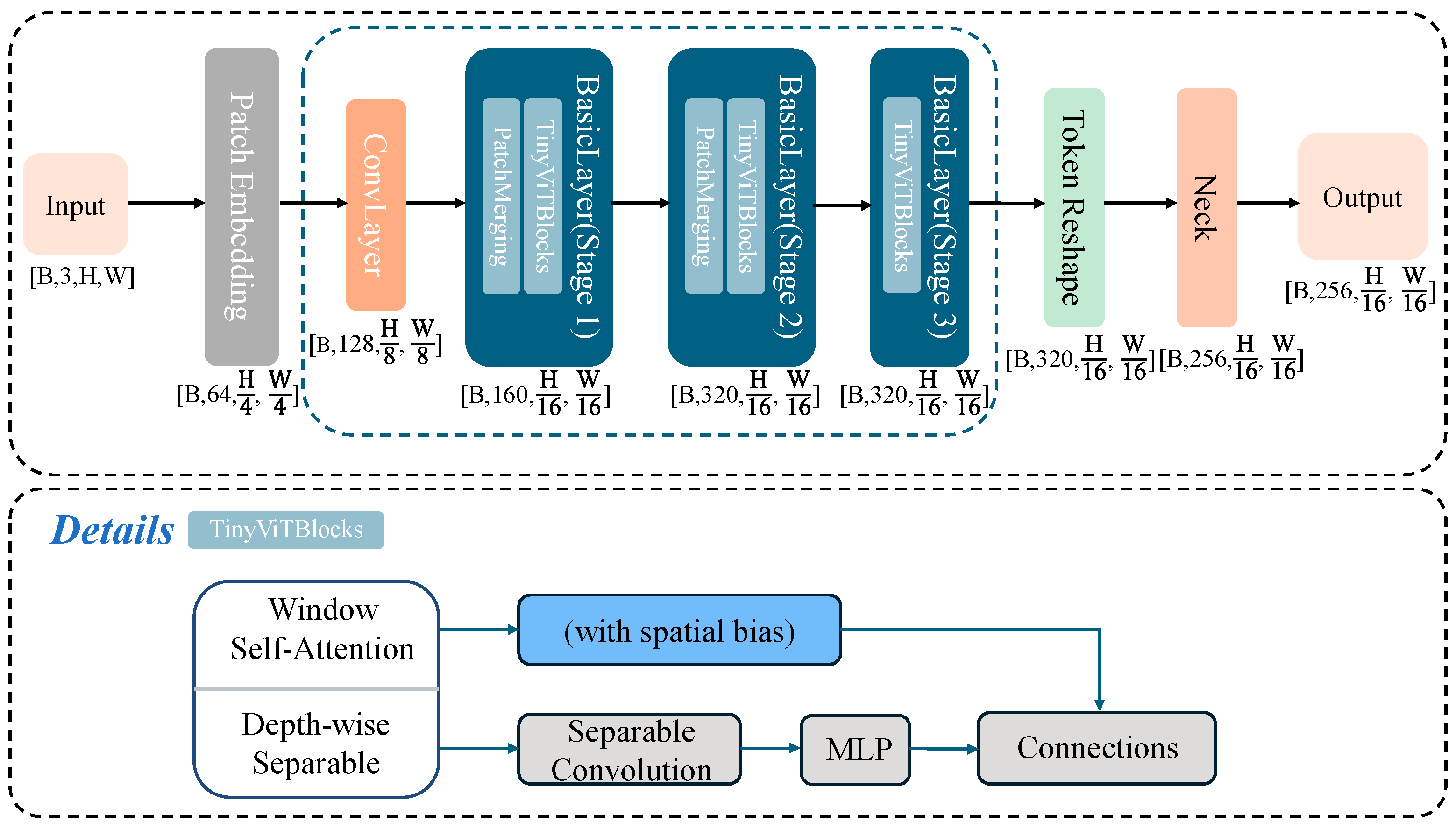

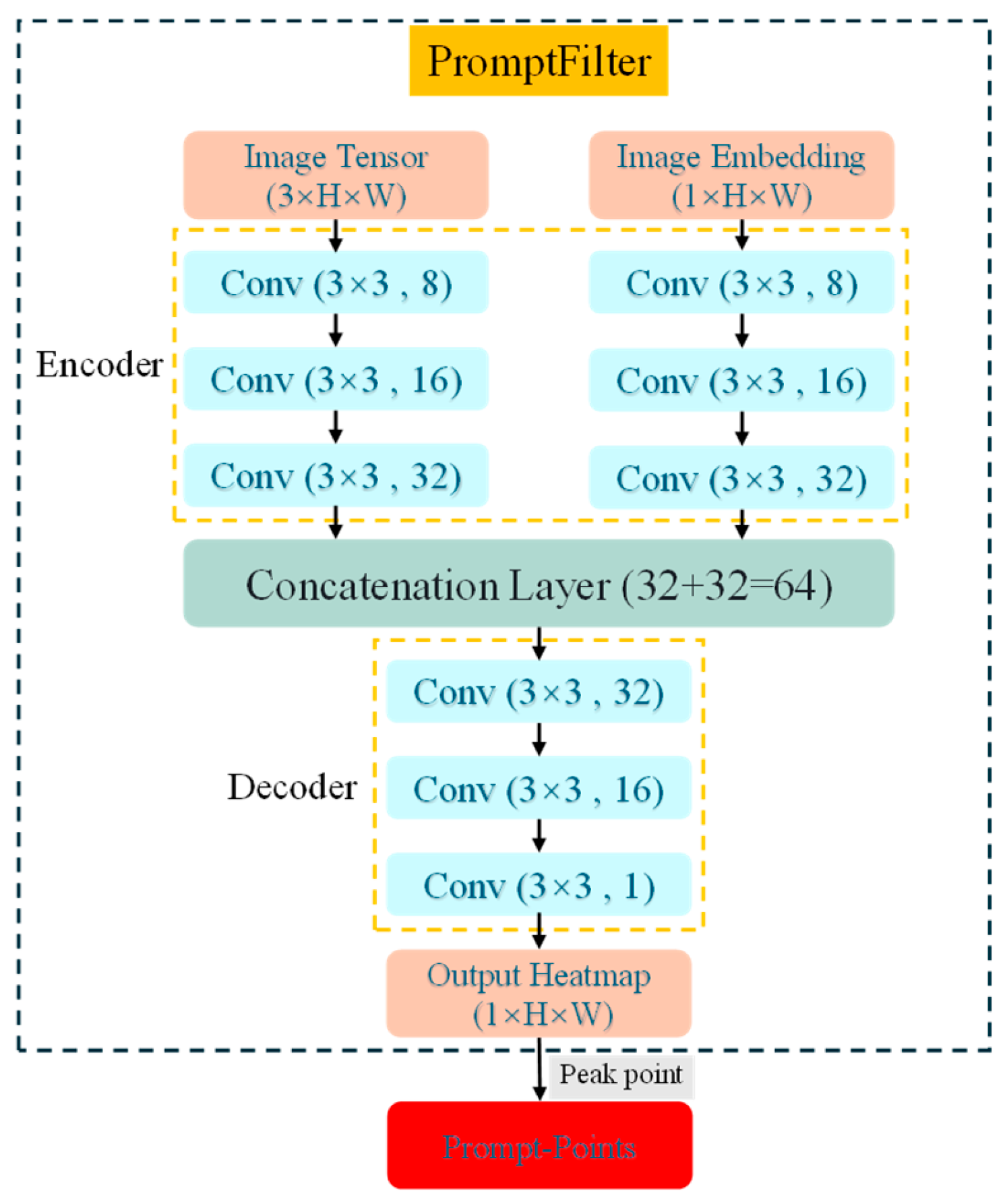

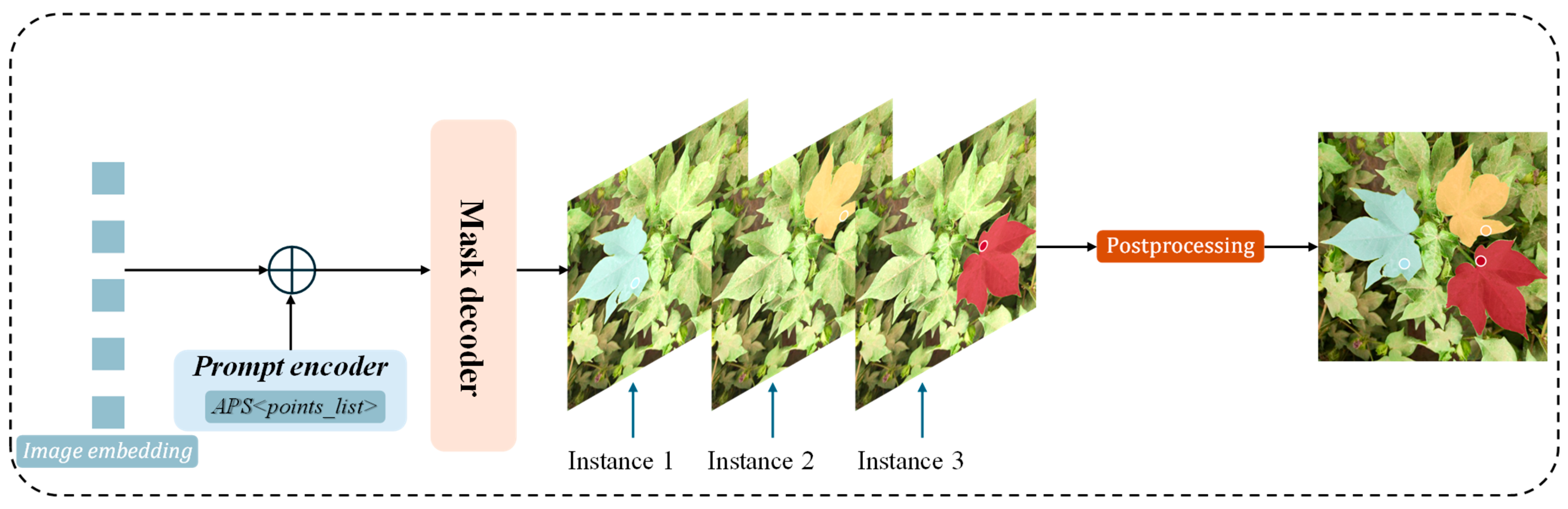

To this end, this paper proposes CF-SAM (A Prompt-Enhanced SAM Model for Instance Segmentation of Terminal Cotton Leaves), an improved SAM-based model tailored for cotton top-leaf instance segmentation. The proposed CF-SAM retains SAM’s zero-shot generalization capability while achieving accurate instance segmentation with a limited dataset. Specifically, the original SAM encoder is replaced with a lightweight Tiny-ViT, and LoRA-based fine-tuning is applied to the encoder–decoder structure for domain adaptation. Moreover, an Adaptive Prompting Strategy (APS) is introduced to automatically generate prompts for cotton top leaves, enabling fully automated end-to-end instance segmentation.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

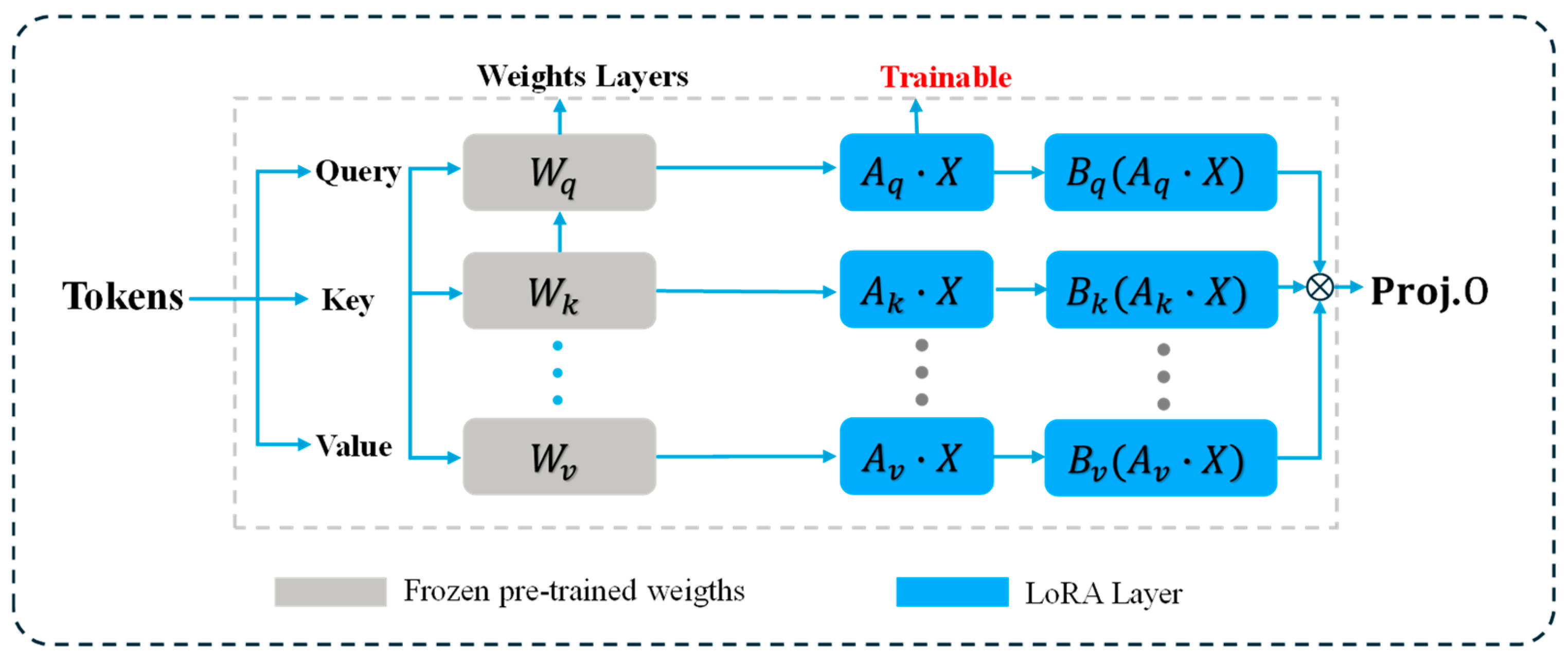

The SAM model is introduced into cotton-leaf segmentation, and its performance on fine structures and weak-texture regions is enhanced via LoRA.

A lightweight Tiny-ViT encoder is utilized to reduce model parameters and inference time while maintaining accuracy.

An automatic point-prompting mechanism (APS) is proposed for cotton top leaves, enabling accurate and efficient automatic prompting.

Due to the lack of publicly available datasets, a self-constructed dataset of cotton apical leaves was developed to evaluate the proposed model. Experimental results demonstrate that CF-SAM produces more accurate segmentation masks with only a minor increase in parameters, thereby providing a solid technical foundation for apical bud localization in cotton plants.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Experimental Environment

To compare the advantages of LoRA, this study used two workstations for model inference and performance evaluation. For inference, CF-SAM used a server with an Intel(R) Xeon(R) E5-2680 CPU and an NVIDIA A100 (40G) GPU. For training and inference, CF-SAM used a personal workstation with an Intel (i7) 12700KF CPU and an NVIDIA 4070 (12G) GPU. Both systems ran on Ubuntu Server 20.04 (64-bit). The CUDA development tool version used was 11.8, combined with the deep learning framework PyTorch 2.4.1. The programming language was Python 3.10. The hyperparameter values set before the experiment are shown in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

3.2. Comparative Experiment

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of CF-SAM, we conducted comparative experiments against several mainstream instance-segmentation frameworks, including Mask R-CNN, YOLO-Seg variants, and the SAM-Base model. The quantitative results are summarized in

Table 4.

Among all competitors, YOLOv11n-seg and YOLOv12n-seg achieved competitive accuracy within the YOLO family. Although Mask R-CNN yielded the highest bounding-box precision for leaf instances, its mask predictions lacked sharpness along leaf boundaries due to its two-stage detection pipeline, which substantially increases computational overhead. Consequently, its inference speed was limited to 55.7 FPS. The baseline SAM-Base exhibited the weakest overall performance. Despite its strong zero-shot generalization capability, it struggled to adapt to fine-grained leaf-segmentation tasks, achieving only P(Mask) = 0.8532 and 13 FPS, while also incurring the largest parameter load (92.3 M) among all models. The Mask R-CNN model, built upon ResNet-50, likewise suffered from heavy parameterization (44.1 M). In contrast, CF-SAM fine-tunes SAM in a parameter-efficient manner by integrating LoRA into its attention layers and updating only the low-rank matrices. This design significantly improves segmentation accuracy on small datasets while maintaining model compactness. With only 0.091 M additional parameters, CF-SAM attains P(Mask) = 0.9804, F1 = 0.9675, and mAP@0.5 = 0.9783, achieving precision comparable to YOLOv12n-seg while sustaining 58 FPS inference—sufficient for real-time field-level automation.

As shown in

Figure 9, SAM-B exhibited clearly suboptimal segmentation performance on this specific task and was highly dependent on the provided prompts. Although the proposed APS strategy was able to supply accurate point prompts within the interior of the top leaf, it still failed to produce a complete and precise segmentation of the entire leaf. This observation further corroborates that, while SAM, as a general-purpose segmentation foundation model, possesses strong generalization ability, its original form does not transfer well to specialized, fine-grained segmentation tasks. As a typical two-stage instance segmentation framework, Mask R-CNN achieved nearly 100% accuracy in predicting bounding boxes for leaf instances; however, its mask predictions for leaf-edge texture were unsatisfactory, and it even misidentified the top leaf in the second image. In contrast, YOLOv12-Seg delivered superior performance, accurately localizing the top leaf and providing more refined segmentation along leaf boundaries. CF-SAM achieved segmentation results comparable to those of YOLOv12-Seg, indicating that, after fine-tuning, the model combined with the proposed APS prompting strategy exhibits strong adaptability and robustness for the segmentation of top leaves in cotton plants.

As illustrated in

Figure 10, the proposed CF-SAM achieves a superior trade-off between accuracy and efficiency compared with the baseline SAM-B model. In terms of network complexity, CF-SAM reduces both the number of trainable parameters and overall model size by approximately one order of magnitude, accompanied by a substantial decrease in FLOPs, indicating a significantly lower computational cost during inference. Despite this drastic reduction in complexity, CF-SAM delivers consistent performance gains: its mIoU and F1-score surpass those of the baseline, demonstrating improved localization accuracy and more stable pixel-level classification. Notably, the parameter increment of CF-SAM is nearly four orders of magnitude lower than that of SAM-B, underscoring the effectiveness of the LoRA-based fine-tuning mechanism in achieving efficient and accurate segmentation.

3.3. Ablation Experiment

To evaluate the effectiveness of each proposed component, a series of ablation studies was conducted on the cotton apical leaf dataset.

As shown in

Table 5, replacing the original encoder with Tiny-ViT drastically reduces both the number of trainable parameters and FLOPs—by approximately one order of magnitude—while maintaining comparable segmentation accuracy. Hence, all subsequent experiments employ Tiny-ViT as the image encoder.

To assess the contribution of LoRA in different attention projections, we applied it individually to the Q, K, and V layers within the image encoder. As reported in

Table 6, fine-tuning only the encoder yields a noticeable improvement in segmentation accuracy, reaching the highest performance when QKV are fine-tuned simultaneously, with merely 0.044 M (0.438%) additional parameters and a 5% improvement over the SAM-Base model.

In contrast, as shown in

Table 7, fine-tuning the mask decoder further enhances segmentation performance. With only 0.047 M (4.63%) additional parameters, the model achieves an 8% accuracy improvement compared to the baseline. This demonstrates that tuning the decoder enables better learning of fine-grained texture and edge information in cotton leaves.

We simultaneously fine-tuned both the image encoder and the mask decoder, and the experimental results are shown in

Table 8. By comparing the performance of applying LoRA to different modules, it was found that fine-tuning the encoder allows the model to learn more feature information of cotton leaves, thus improving segmentation accuracy. Fine-tuning the decoder allows the model to learn a more complete cotton leaf texture and edge information, thus improving segmentation quality. Experimental results show that the segmentation quality is optimal when both the encoder and decoder are fine-tuned simultaneously, achieving a 13% improvement in segmentation accuracy compared to SAM-base with only a 0.091M (0.8%) increase in parameters.

As shown in

Figure 11, the visualization results of fine-tuning different layers and projection modules are presented. (a) and (b) represent the cases where only the encoder is fine-tuned, with rank = 4 matrices inserted into qv and qkv, respectively. (c) and (d) represent the cases where only the decoder is fine-tuned, with rank = 4 matrices inserted into qkv and qkvo, respectively. (e) and (f) represent the visualization results when both the encoder and decoder are fine-tuned simultaneously, using matrices with ranks = 2 and 4, respectively.

The visualization results show that fine-tuning only the encoder or decoder leads to inaccurate segmentation of leaf edges. As illustrated in (e) and (f), when both the encoder and decoder are fine-tuned simultaneously, the model achieves a higher level of segmentation performance, enabling more precise delineation of leaf boundaries. The model exhibits the best segmentation quality when the rank size is set to 4.

We also compared the impact of different rank sizes on segmentation accuracy by inserting low-rank matrices of different rank sizes into the multi-head self-attention mechanism, cross-attention mechanism, and mask attention mechanism of the image encoder and mask decoder. The results are shown in

Table 9.

Experimental results show that fine-tuning with different rank sizes can achieve comparable results. The model’s segmentation ability is strongest when the rank of the low-rank matrix is 4, with P(Mask) reaching 98% and mIoU 0.916, while achieving a trade-off in parameter increment. When the rank is greater than 4, performance decreases, indicating that excessively large rank can cause the model to learn more redundant features, leading to a sparse feature matrix and thus affecting segmentation accuracy.

3.4. Demonstration

To further illustrate the practical effectiveness of the proposed CF-SAM, we present a series of qualitative demonstrations on cotton images from the test set and additional field scenes. Representative examples show the APS-generated point prompts, the predicted masks, and their overlays on the original images. Notably, the test-set demonstrations explicitly include challenging dust-haze samples; for example, the cases shown in

Figure 12c–e were all collected under dust-haze conditions. This qualitative evidence complements the quantitative evaluation by illustrating the robustness of CF-SAM under severe atmospheric interference. Compared with the baseline SAM-B and other competing methods, CF-SAM produces more complete top-leaf contours, sharper leaf edges, and fewer false positives on background regions. The qualitative results also indicate that CF-SAM maintains stable segmentation performance under variations in illumination, background clutter, and partial occlusion, demonstrating its suitability for real-field deployment and downstream automated phenotyping applications.

4. Discussion

The proposed CF-SAM model demonstrates superior performance in cotton apical leaf segmentation under complex field conditions. By fine-tuning the large SAM model with LoRA on a small dataset, CF-SAM substantially improves fine-grained segmentation accuracy while maintaining zero-shot generalization. Compared with the untuned SAM-Base (P(Mask) ≈ 0.85), CF-SAM achieves P(Mask) = 0.98 and mAP@50 = 97.83% with only 0.09M additional parameters. Replacing ViT-B with Tiny-ViT reduces parameters from 92.3M to 13.5M, improving inference efficiency nearly tenfold without compromising accuracy. These results verify that lightweight architectures can achieve real-time segmentation on resource-constrained agricultural machinery.

The Adaptive Prompting Strategy (APS) enables automatic end-to-end segmentation. By generating high-quality point cues via CNN, APS guides SAM to focus precisely on top-leaf regions, removing the need for manual prompts. It performs reliably across varying illumination and occlusion but shows limited robustness when leaves are heavily overlapped or backgrounds are highly cluttered. For example, as shown in

Figure 13c, APS may mistakenly select a young inner leaf as a top-layer target, which can further degrade the segmentation quality.

Methodologically, CF-SAM illustrates that large vision models can be effectively adapted to agricultural tasks using small datasets through efficient fine-tuning. With only 1000 training images, the model achieves high accuracy and compactness, proving the feasibility of transferring pretrained general models to agricultural scenarios. The introduction of Tiny-ViT further enhances portability, making CF-SAM deployable on embedded and edge devices.

Nevertheless, given the substantial variability of real-world field environments, the current dataset—although collected under diverse conditions (e.g., clear-sky, overcast, and dust-haze)—remains moderate in both size and coverage for instance segmentation. Moreover, all images were acquired within a single region and season, which may constrain external validity when deploying the model across different cotton cultivars, growth stages, and geographic areas. Future work will therefore expand data collection across regions and varieties and incorporate cross-region and cross-dataset evaluations to more rigorously assess generalization.

In addition, APS currently supports only single-plant segmentation. Future work will focus on multi-target extension and integrating geometric reasoning or depth cues to improve robustness and bud localization.

In summary, CF-SAM combines accuracy, efficiency, and automation, providing a practical framework for intelligent cotton topping and demonstrating the potential of large-model adaptation in agricultural vision.

5. Conclusions

This paper explores a novel approach to indirect bud localization in cotton plants and develops an end-to-end segmentation model, CF-SAM, for segmenting top leaf instances. We introduce the general segmentation model SAM into agricultural scenarios and significantly improve its segmentation accuracy and practicality under limited data conditions through innovative combinations of LoRA fine-tuning, Tiny-ViT lightweighting, and adaptive prompting strategies. Experimental results show that CF-SAM achieves significant advantages in accuracy (more than 5% improvement in P(Mask) and mAP@50 metrics) compared to traditional detection and segmentation methods, requiring only minimal additional training parameters. The prompting mechanism, which eliminates the need for manual interaction, automates the top leaf segmentation process, laying the foundation for precise bud localization by intelligent topping machines. This work demonstrates the feasibility and efficiency of adapting a large model to small sample sizes in precision agriculture.

In practical applications, CF-SAM holds promise for integration into field operation platforms, such as drones or self-propelled topping machines, to segment the top leaves of cotton plants. This will improve the intelligence level of cotton topping operations and reduce reliance on human experience. However, we also recognize the limitations of this study: the model’s robustness to extreme occlusion conditions and its cross-environment generalization ability require further verification. In future work, we plan to collect larger-scale, multi-regional cotton plant image data to train and test the model, continuously improving its adaptability and reliability. Simultaneously, we can explore methods such as multi-point prompts and multimodal information fusion to improve the APS strategy and enhance segmentation accuracy in complex scenarios. We will also attempt to extend this method to the identification of key parts of other crops, verifying its universality and effectiveness in broader precision agriculture applications. In conclusion, CF-SAM provides a new technical approach for precise topping of cotton buds and offers valuable experience and insights for the application of deep learning models in agriculture.