Construction of a Prediction Model for Functional Traits of Grape Leaves Based on Multi-Stage Collaborative Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

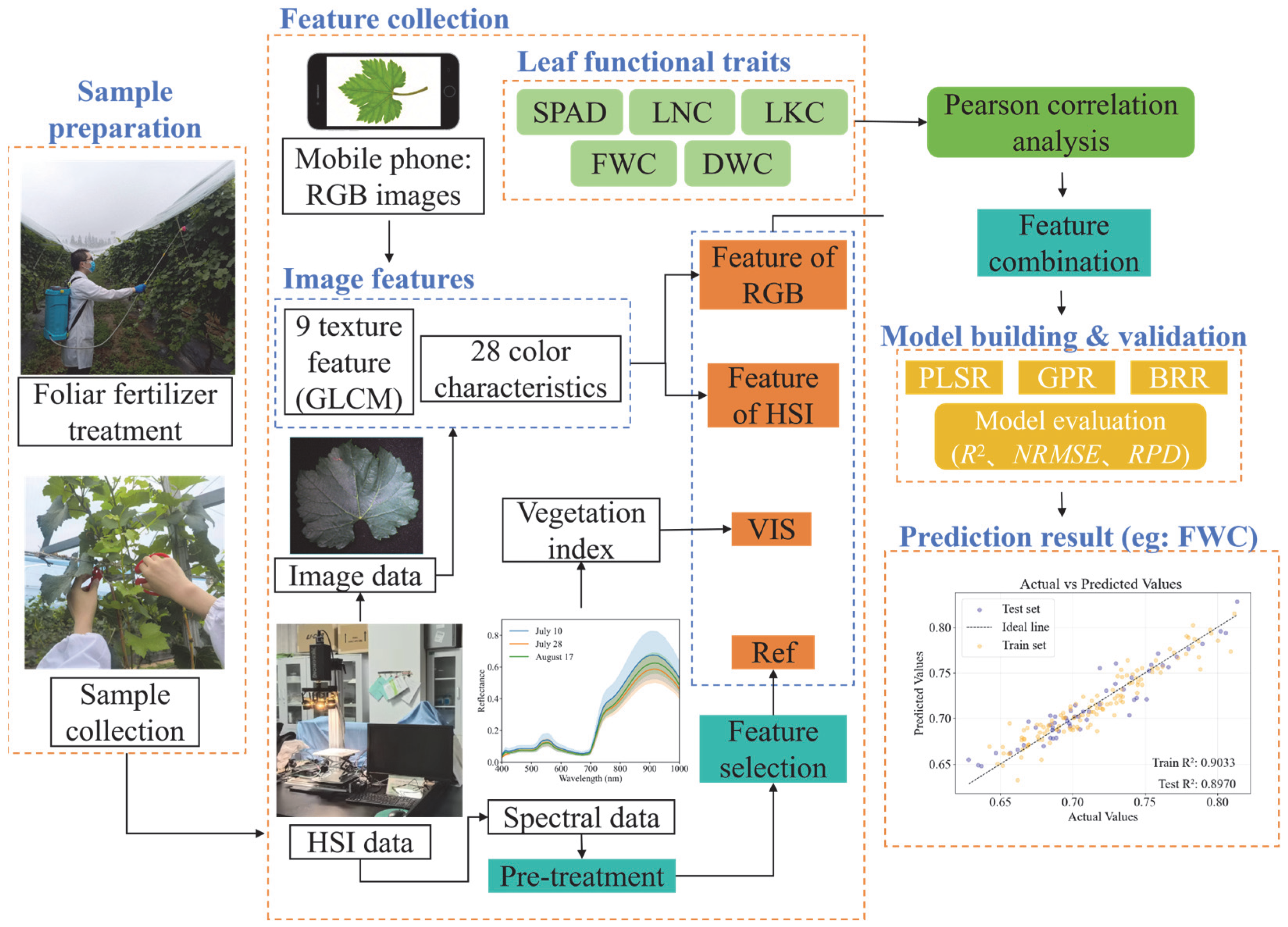

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Data Acquisition

2.2.1. Leaf Reflectance Measurement

2.2.2. Measurement of Leaf Functional Traits

2.3. Spectral Preprocessing Techniques

2.4. Feature Collection for the Prediction of Leaf Traits

2.4.1. Feature Selection Methodology

2.4.2. Vegetation Indices

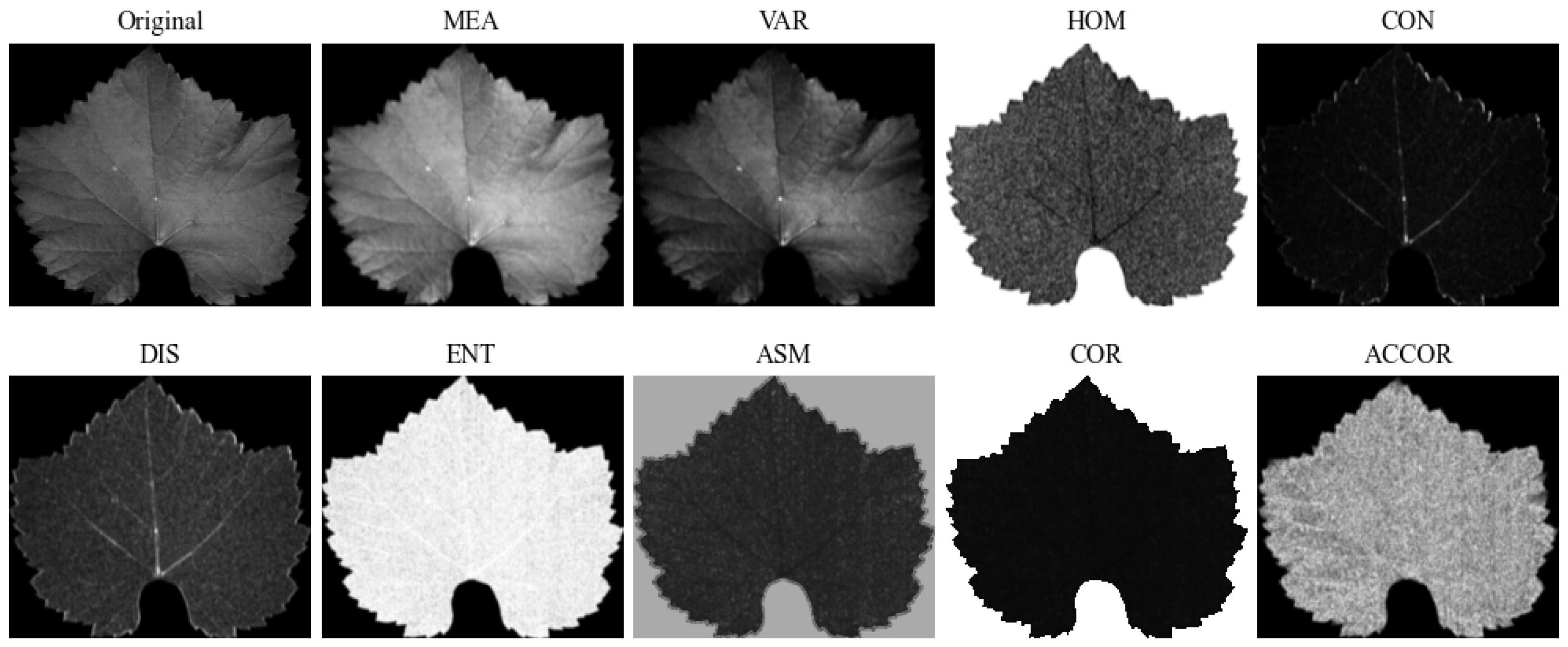

2.4.3. Texture Information Extraction

2.4.4. Color Feature Extraction

2.5. Regression Algorithm

2.6. Model Performance Evaluation

3. Results

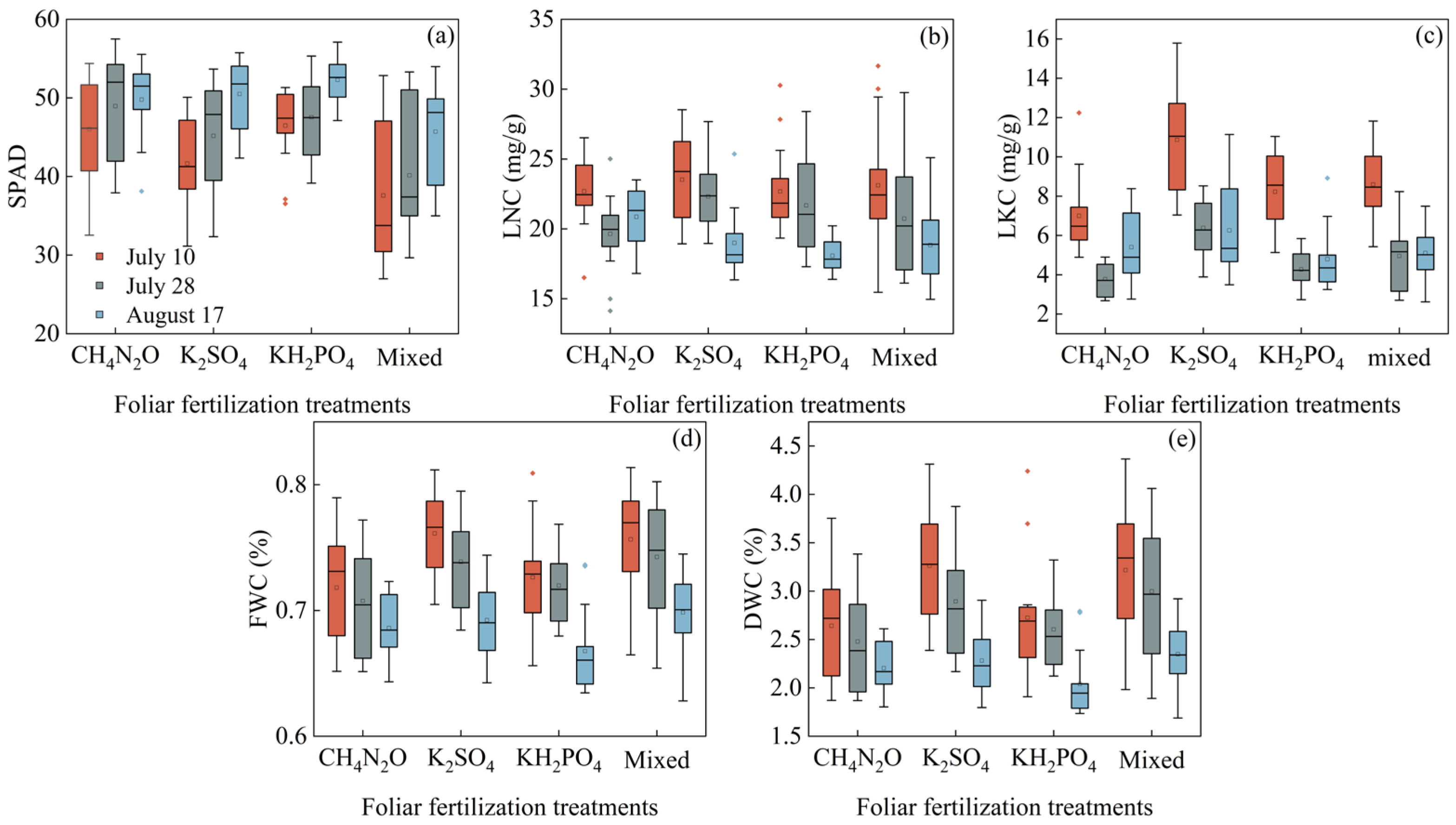

3.1. Leaf Functional Traits

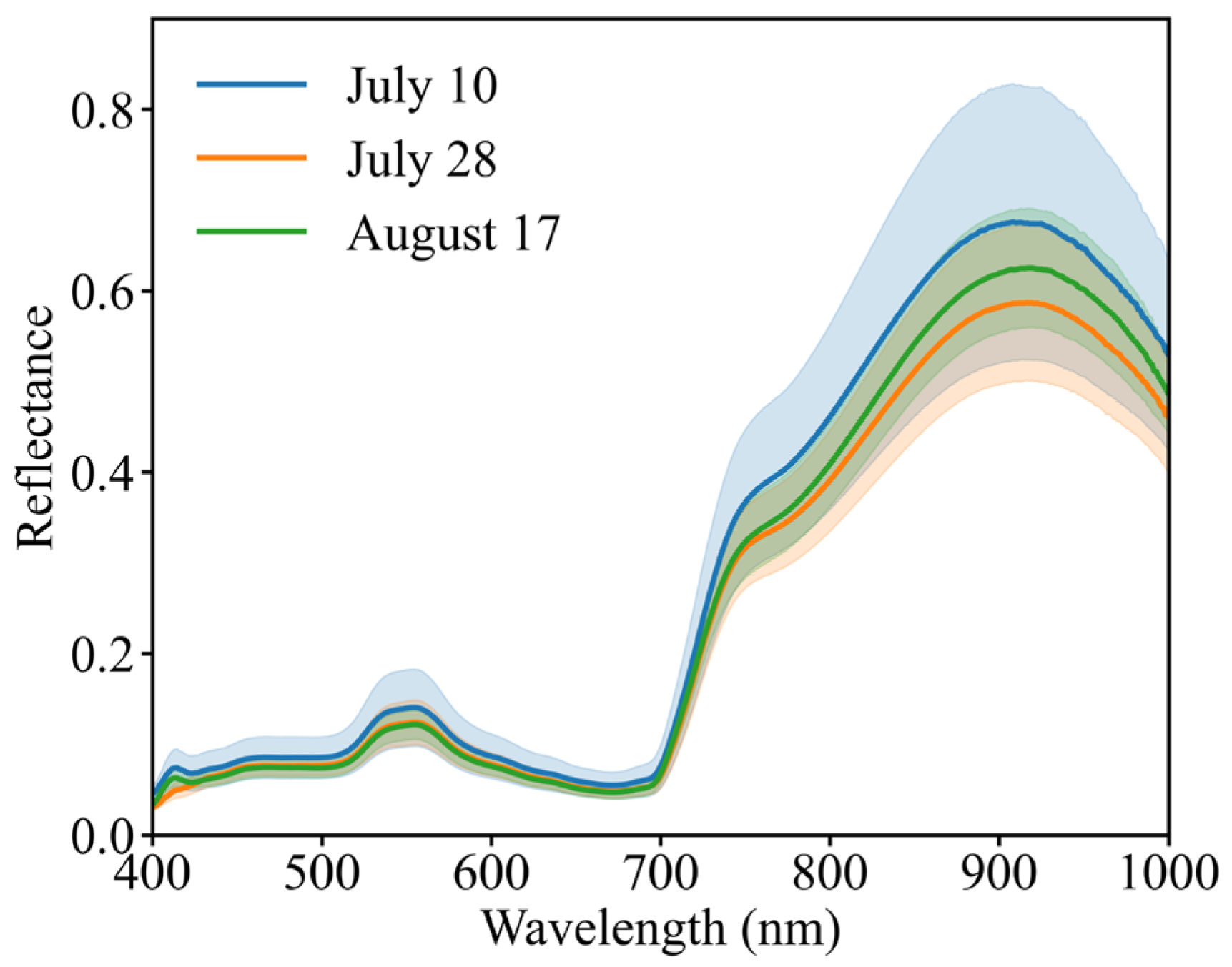

3.2. Original Spectra

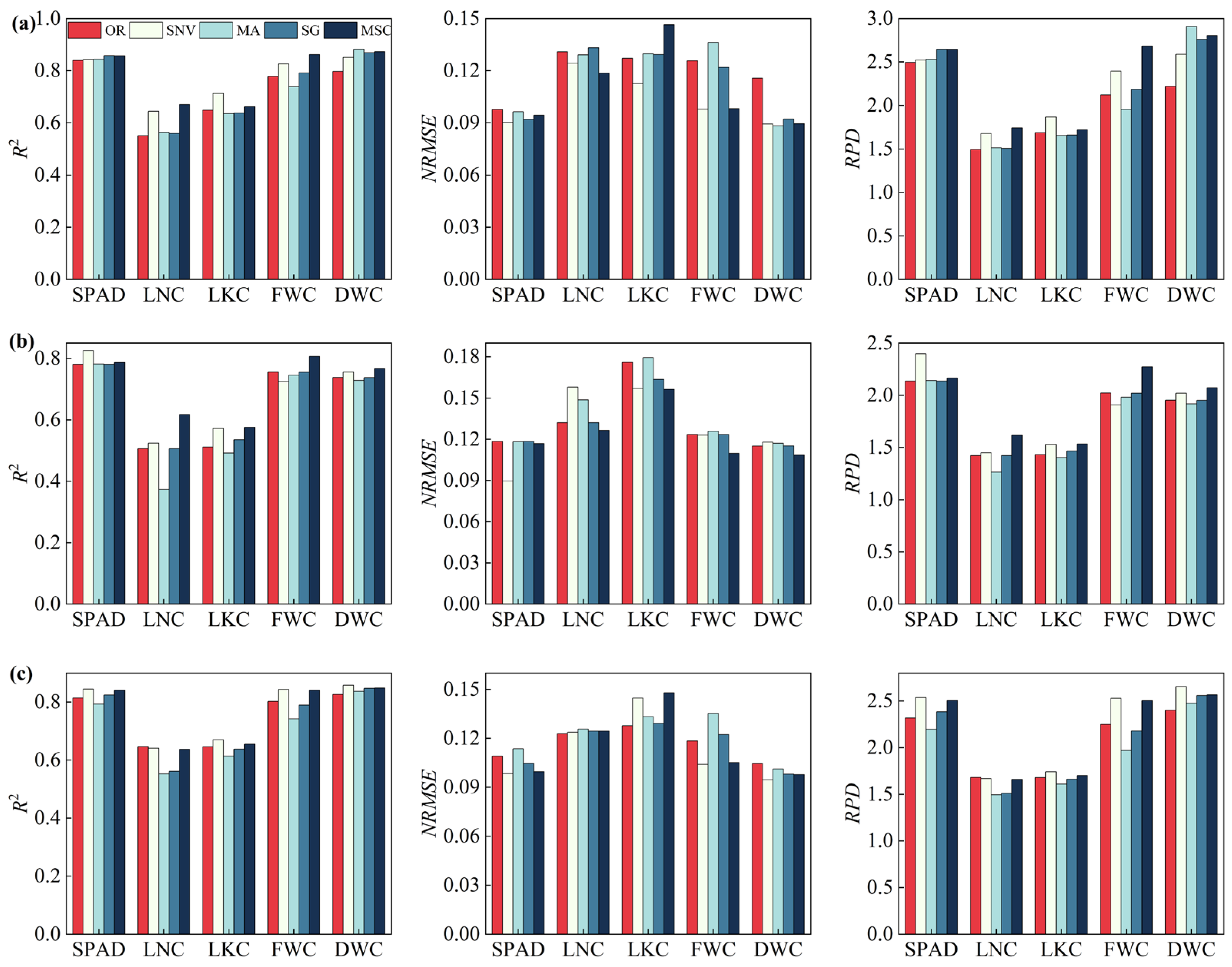

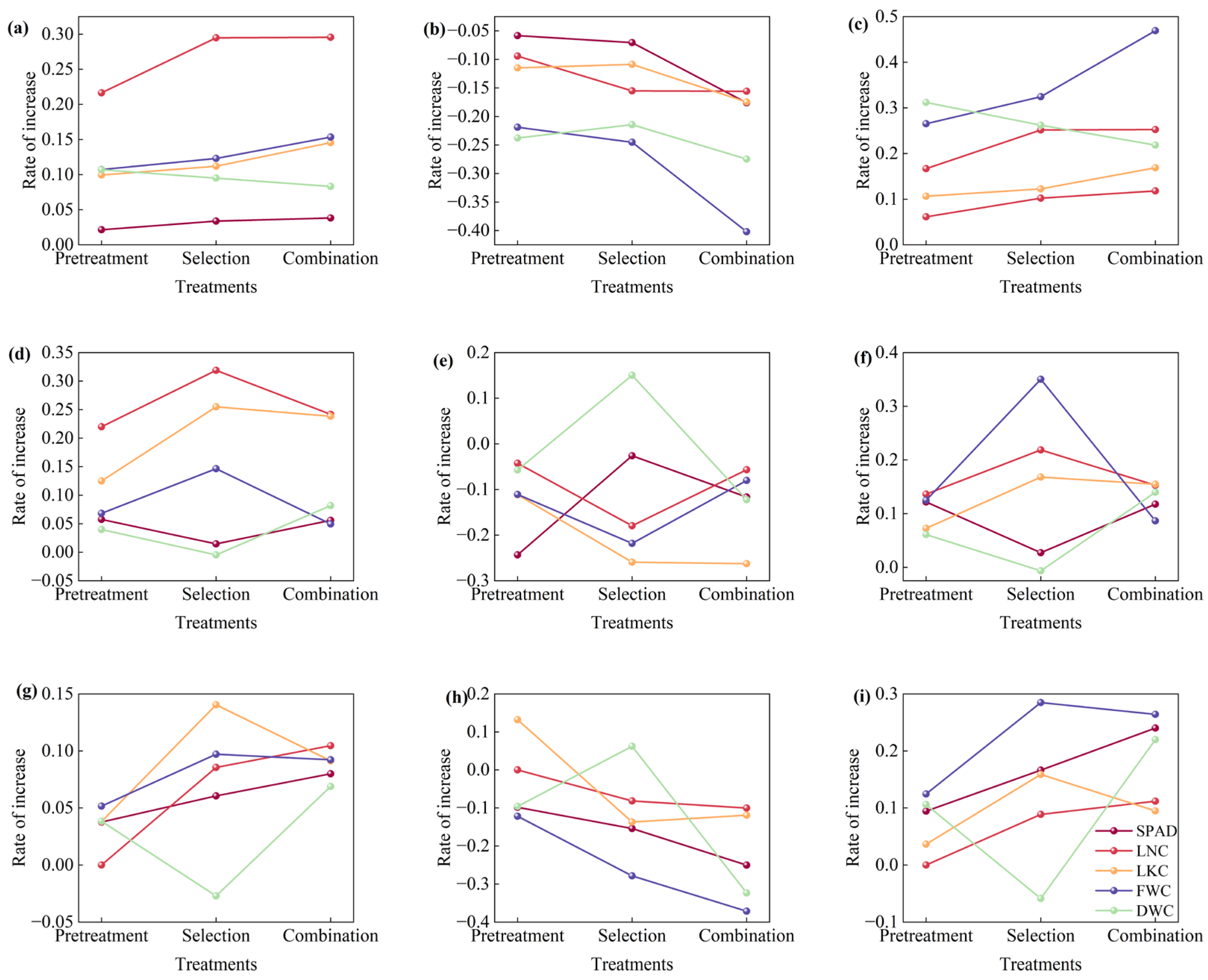

3.3. Optimal Pretreatment Selection

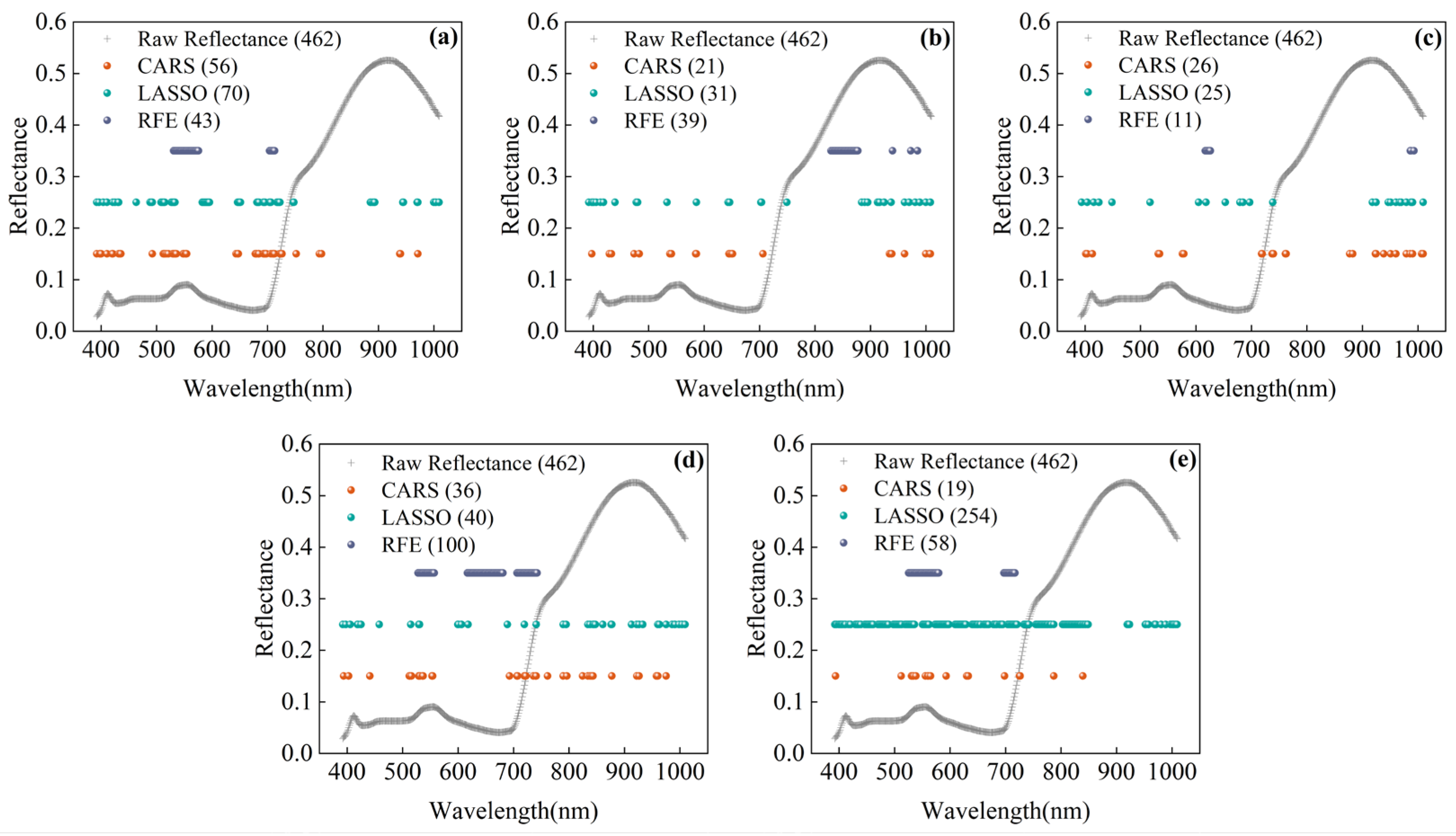

3.4. Feature Selection

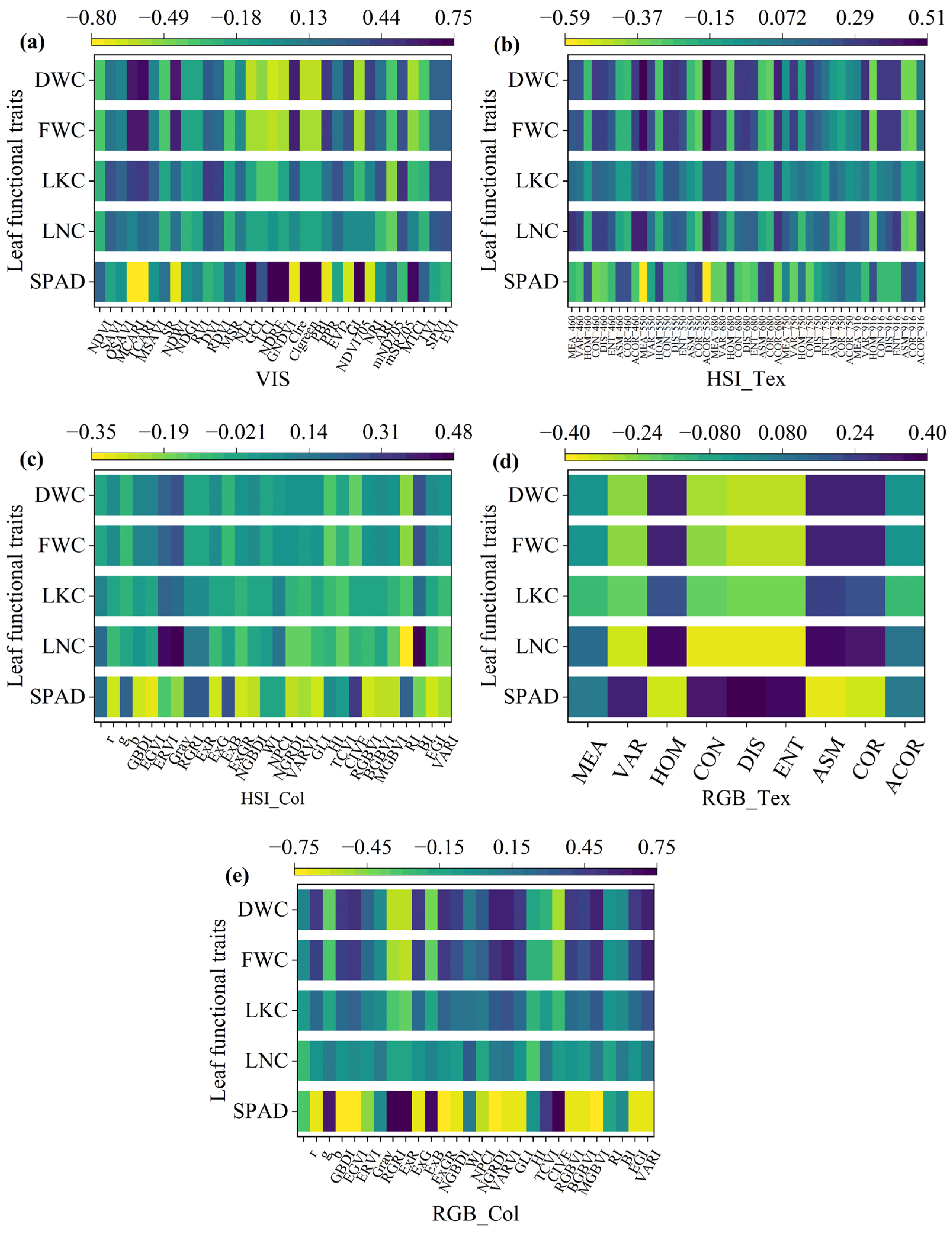

3.5. Correlation Analysis of Relationships Between Different Features and Leaf Functional Traits

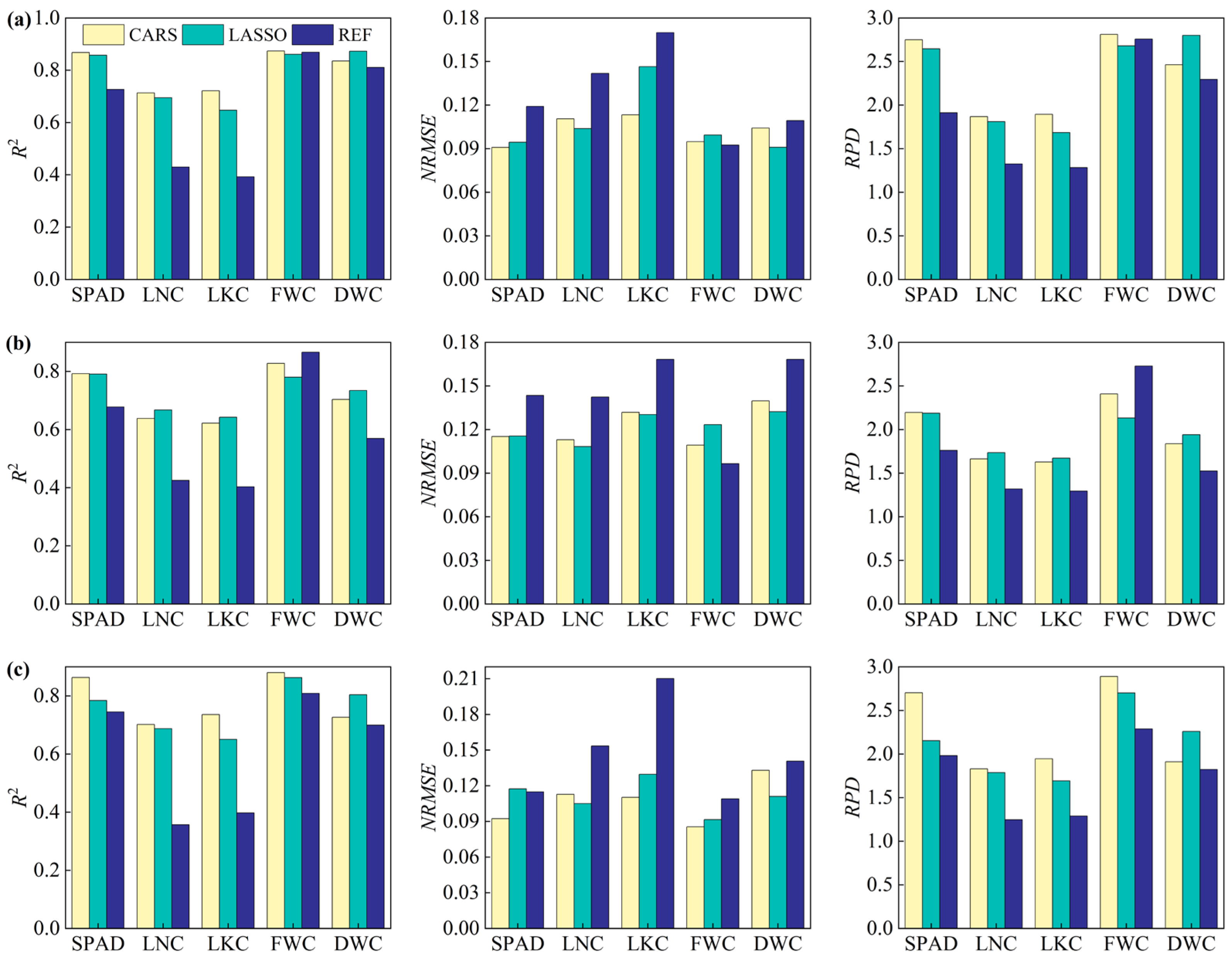

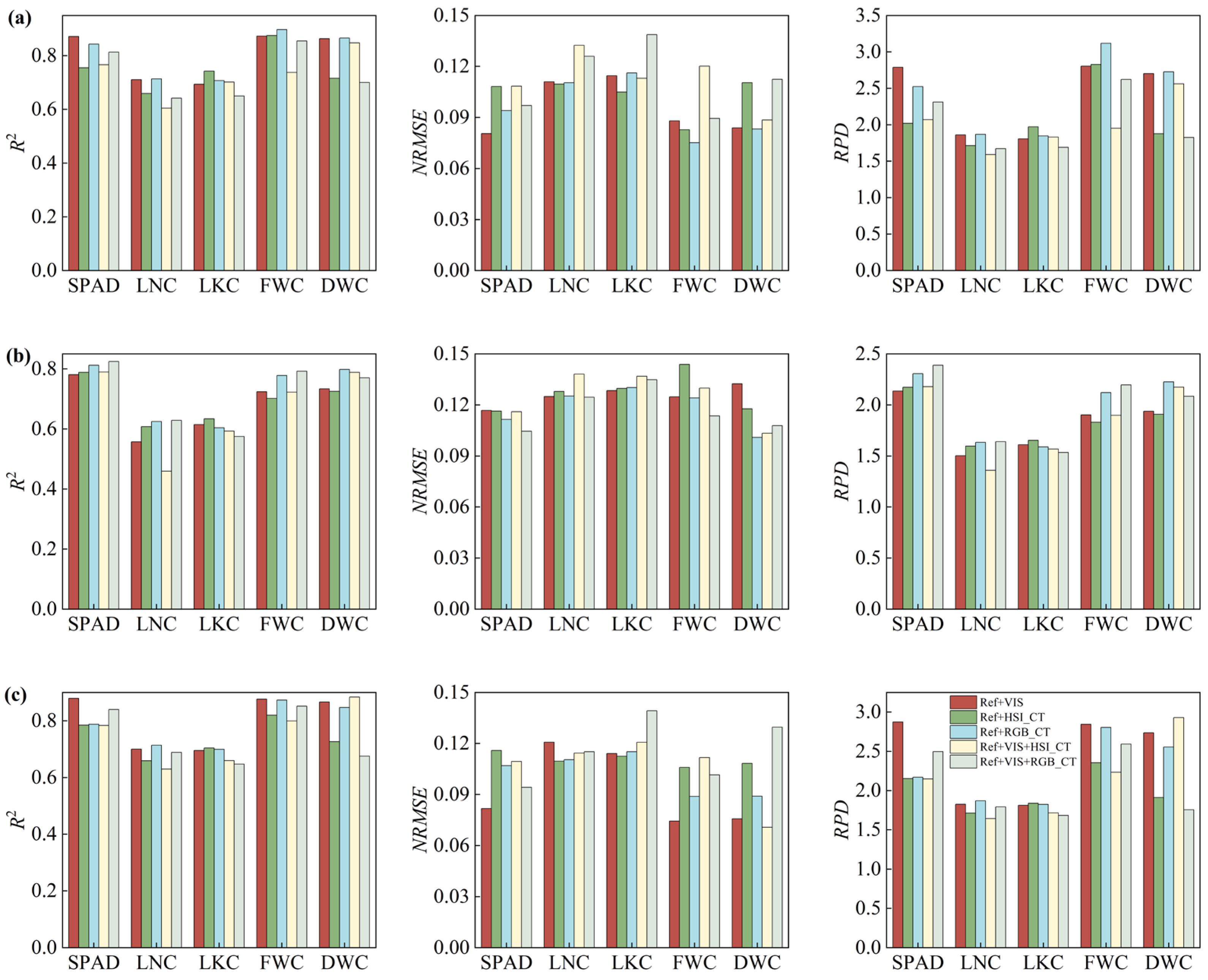

3.6. Performance of Feature Combination Leaf Functional Traits

4. Discussion

4.1. Contribution of Feature Types to Leaf Trait Prediction

4.2. Effect of Different Optimization Methods on Model Performance

4.3. Characteristics of Regression Algorithms in Leaf Trait Prediction

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jetz, W.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Pavlick, R.; Schimel, D.; Davis, F.W.; Asner, G.P.; Guralnick, R.; Kattge, J.; Latimer, A.M.; Moorcroft, P. Monitoring plant functional diversity from space. Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 16024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruelheide, H.; Dengler, J.; Purschke, O.; Lenoir, J.; Jiménez-Alfaro, B.; Hennekens, S.M.; Botta-Dukát, Z.; Chytry, M.; Field, R.; Jansen, F.; et al. Global trait-environment relationships of plant communities. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 2, 1906–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Y.; Liu, Y.M.; Wang, H.Y.; Dong, X.Z.; Wang, L.; Long, Y.Q. Comparing Stacking Ensemble Learning and 1D-CNN Models for Predicting Leaf Chlorophyll Content in Stellera chamaejasme from Hyperspectral Reflectance Measurements. Agriculture 2025, 15, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Wagner, H.E.; Hansen, N.T.P.A. Multi-year hyperspectral remote sensing of a comprehensive set of crop foliar nutrients in cranberries. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 205, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Li, Y.; Du, S.; Zheng, Y.; Gao, J.; Sun, T. Effect of dust deposition on spectrum-based estimation of leaf water content in urban plant. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 104, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correspondence, J.; Kattge, J.; Bnisch, G.; Diaz, S.; Wirth, C. TRY plant trait database—enhanced coverage and open access. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 119–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Cheng, X.; Du, R.; Zhu, X.; Guo, W. Detection of chlorophyll content based on optical properties of maize leaves. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 309, 123843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watt, M.S.; Buddenbaum, H.; Leonardo, E.M.C.; Estarija, H.J.C.; Bown, H.E.; Gomez-Gallego, M.; Hartley, R.; Massam, P.; Wright, L.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J. Using hyperspectral plant traits linked to photosynthetic efficiency to assess N and P partition. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 169, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Tang, T.; Duan, Y.X.; Li, J.L.; Ling, C.J.; Gao, T.; Wu, W.B. Nitrogen-phosphorus responses and Vis/NIR prediction in fresh tea leaves. Food Chem. 2025, 476, 143369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azadnia, R.; Rajabipour, A.; Jamshidi, B.; Omid, M. New approach for rapid estimation of leaf nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium contents in apple-trees using Vis/NIR spectroscopy based on wavelength selection coupled with machine learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 207, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.F.; Xu, X.A.; Wu, W.B.; Zhu, Y.H.; Gao, L.T.; Jiang, X.T.; Meng, Y.; Yang, G.J.; Xue, H.Y. Hyperspectral estimation of chlorophyll content in grapevine based on feature selection and GA-BP. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.F.; Li, Y.J.; Yuan, N.G.; Liu, X.J.; Yan, Y.Y.; Zhang, C.R.; Fang, S.H.; Gong, Y. The Inversion of Rice Leaf Pigment Content: Using the Absorption Spectrum to Optimize the Vegetation Index. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.J.; Zhang, Z.M.; Zhang, A.Z.; Sun, G.Y.; Wu, L.X. Modified Multiple Spectrum-Based Vegetation Index (MMSVI): A Reflectance Index With High Spatiotemporal Generalization Ability. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Tian, J.; Feng, K.; Gong, X.; Liu, J. Application of a hyperspectral imaging system to quantify leaf-scale chlorophyll, nitrogen and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters in grapevine. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 166, 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.S.; Zhang, F.; Tan, M.L.; Chan, N.W.; Shi, J.C.; Liu, C.J.; Wang, W.W. Improved Na+ estimation from hyperspectral data of saline vegetation by machine learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 196, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zhao, W.; Yu, H.; Yang, P.; Yang, F.; Li, Z. Diagnosis alfalfa salt stress based on UAV multispectral image texture and vegetation index. Plant Soil 2024, 513, 585–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, A.; Khani, S.; Sabourian, R.; Hajimahmoodi, M.; Ghasemi, J.B. Integrating CNNs and chemometrics for analyzing NIR spectra and RGB images in turmeric adulterant detection. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 141, 107324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.M.E.; Petropoulos, S.A.; Selim, D.; Elbagory, M.; Othman, M.M.; Omara, A.E.; Mohamed, M.H. Plant Growth, Yield and Quality of Potato Crop in Relation to Potassium Fertilization. Agronomy 2021, 11, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.M.; Huang, H.; He, X.L.; Cai, J.W.; Zeng, Z.X.; Ma, C.Y.; Lü, E.L.; Shen, Q.Y.; Liu, Y.H. Improving the detection accuracy of the nitrogen content of fresh tea leaves by combining FT-NIR with moisture removal method. Food Chem. 2023, 405, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.H.; Otani, C.; Ogawa, Y. Innovatively identifying naringin and hesperidin by using terahertz spectroscopy and evaluating flavonoids extracts from waste orange peels by coupling with multivariate analysis. Food Control 2022, 137, 108897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Q.; Wang, L.; Park, B.; Kang, R.; Chen, Q. Simultaneous quantification of chemical constituents in matcha with visible-near infrared hyperspectral imaging technology. Food Chem. 2021, 350, 129141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mbaideen, A.A. Application of Moving Average Filter for the Quantitative Analysis of the NIR Spectra. J. Anal. Chem. 2019, 74, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaie, M.; Darvishzadeh, R.; Shakiba, A.; Matkan, A.A.; Atzberger, C.; Skidmore, A. Comparative analysis of different uni- and multi-variate methods for estimation of vegetation water content using hyper-spectral measurements (vol 26, pg 1, 2014). Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2014, 28, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Du, R.Q.; Xiang, Y.Z.; Chen, J.Y.; Zhang, F.C.; Shi, H.Z.; Tang, Z.J.; Wang, X. Estimating Winter Canola Aboveground Biomass from Hyperspectral Images Using Narrowband Spectra-Texture Features and Machine Learning. Plants 2024, 13, 2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Wei, H.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, N.; Zheng, H.; Qiao, X.; Liu, D. A multi-feature fusion based method for detecting the moisture content of withered black tea. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 141, 107325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Struik, P.C.; Liang, L.; Yin, X.Y. Estimating leaf and canopy nitrogen contents in major field crops across the growing season from hyperspectral images using nonparametric regression. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 233, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, A.C.; Jeremiah, A.; Davidson, K.J.; Ely, K.S.; Julien, L.; Qianyu, L.; Morrison, B.D.; Dedi, Y.; Alistair, R.; Serbin, S.P. A best-practice guide to predicting plant traits from leaf-level hyperspectral data using partial least squares regression. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 6175–6189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bureau, S.; Jaillais, B.; Renard, C.M.G.C.; Chen, X.; Sun, Y.; Lv, D.; Pan, L.; Lan, W. Infrared guided smart food formulation: An innovative spectral reconstruction strategy to develop anticipated and constant apple puree products. Food Innov. Adv. 2024, 3, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Darvishzadeh, R.; Skidmore, A.K.; Heurich, M.; Holzwarth, S.; Gara, T.W.; Reusen, I. Mapping leaf area index in a mixed temperate forest using Fenix airborne hyperspectral data and Gaussian processes regression. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 95, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liu, J. Near-infrared spectral expansion method based on active semi-supervised regression. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1317, 342890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, J.; Liu, X. Combined application of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers increases soil organic carbon storage in cropland soils. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 168, 127607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, J.; Wang, J.; Xie, L.W.; Xiang, L.; Wang, Z. Spectroscopic determination of chlorophyll content in sugarcane leaves for drought stress detection. Precis. Agric. 2024, 25, 543–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, S.; Zhang, W.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Mei, Z.; Yan, J.; Li, M. Comparison of Citrus Leaf Water Content Estimations Based on the Continuous Wavelet Transform and Fractional Derivative Methods. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xiao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Meng, X.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, C.; Ren, L.; Yang, C. Hyperspectral Estimation of Winter Wheat Leaf Water Content Based on Fractional Order Differentiation and Continuous Wavelet Transform. Agronomy 2022, 13, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, P.J. Remote sensing of foliar chemistry. Remote Sens. Environ. 1990, 30, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Wang, H.; Liao, Z.; Dai, Y.; Yu, J.; Feng, H. Winter Wheat Leaf Area Index Estimation Based on Texture-color Features and Vegetation Indices. J. China Agric. Univ. 2023, 54, 7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, P.K.; Somasundaram, E.; Krishnan, R.; Radhamani, S.; Sivakumar, U.; Parameswari, E.; Raja, R.; Rangasami, S.R.S.; Sangeetha, S.P.; Selvi, R.G. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle-Measured Multispectral Vegetation Indices for Predicting LAI, SPAD Chlorophyll, and Yield of Maize. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, A.; Riaño, D.; Ustin, S.L.; Dennison, P.; Salas, J. Estimation of water-related biochemical and biophysical vegetation properties using multitemporal airborne hyperspectral data and its comparison to MODIS spectral response. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 148, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Yan, K.; Lu, X.; Li, W.; Tian, H.; Wang, L.; Deng, J.; Lan, Y. Advances and Developments in Monitoring and Inversion of the Biochemical Information of Crop Nutrients Based on Hyperspectral Technology. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Lan, Y.; Hong, T.; Chen, J. Citrus greening detection using visible spectrum imaging and C-SVC. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2016, 130, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Li, J.Q.; Zhang, J.Q.; Yang, L.; Cui, W.H.; Han, X.W.; Qin, D.L.; Han, G.T.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, Z.S.; et al. Estimation of Cotton SPAD Based on Multi-Source Feature Fusion and Voting Regression Ensemble Learning in Intercropping Pattern of Cotton and Soybean. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Jayan, H. Fast Nondestructive Detection Technology and Equipment for Food Quality and Safety. Foods 2023, 12, 3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Liang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Cao, D. Key wavelengths screening using competitive adaptive reweighted sampling method for multivariate calibration. Anal. Chim. ACTA 2009, 648, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebalam, H.; Gholizadeh, M.; Hafezian, H. Investigating the Performance of Frequentist and Bayesian Techniques in Genomic Evaluation. Biochem. Genet. 2025, 63, 3240–3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvenaud, D.; Lloyd, J.R.; Grosse, R.; Tenenbaum, J.B.; Ghahramani, Z. Structure Discovery in Nonparametric Regression through Compositional Kernel Search. In OTM Confederated International Conferences “On the Move to Meaningful Internet Systems”; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Gao, P.; Yin, H.; Chen, S.; Sun, D.; Wang, W.; Mo, H.; Shen, J. Estimating the SPAD of Litchi in the Growth Period and Autumn Shoot Period Based on UAV Multi-Spectrum. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimaitijiang, M.; Sagan, V.; Sidike, P.; Hartling, S.; Fritschi, F.B. Soybean yield prediction from UAV using multimodal data fusion and deep learning. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 237, 111599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.J. Red and photographic infrared linear combinations for monitoring vegetation. Remote Sens. Environ. 1979, 8, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.R.; Liu, H.Q.; Batchily, K.; van Leeuwen, W. A comparison of vegetation indices global set of TM images for EOS-MODIS. Remote Sens. Environ. 1997, 59, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondeaux, G.; Steven, M.; Baret, F. Optimization of soil-adjusted vegetation indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 55, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daughtry, C.S.T.; Walthall, C.L.; Kim, M.S.; Colstoun, E.B.D.; Iii, M.M. Estimating Corn Leaf Chlorophyll Concentration from Leaf and Canopy Reflectance. Remote Sens. Environ. 2000, 74, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haboudane, D.; Miller, J.R.; Tremblay, N.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Dextraze, L. Integrated narrow-band vegetation indices for prediction of crop chlorophyll content for application to precision agriculture. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 81, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.G.; Chehbouni, A.R.; Huete, A.R.; Kerr, Y.H.; Sorooshian, S. A Modified Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index. Remote Sens. Environ. 1994, 48, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penuelas, J.; Gamon, J.A.; Griffin, K.L.; Field, C.B. Assessing Community Type, Plant Biomass, Pigment Composition, and Photosynthetic Efficiency of Aquatic Vegetation from Spectral Reflectance. Remote Sens. Environ. 1993, 46, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFEETERS, S.K. The use of the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) in the delineation of open water features. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1996, 17, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Kobayashi, H.; Wang, C.; Shen, M.G.; Chen, J.; Matsushit, B.; Tang, Y.H.; Kim, Y.; Bret-Harte, M.S.; Zona, D.; et al. A semi-analytical snow-free vegetation index for improving estimation of plant phenology in tundra and grassland ecosystems. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 228, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Mishra, D.R. Normalized difference chlorophyll index: A novel model for remote estimation of chlorophyll-a concentration in turbid productive waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 117, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roujean, J.L.; Breon, F.M. Estimating Par Absorbed by Vegetation from Bidirectional Reflectance Measurements. Remote Sens. Environ. 1995, 51, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M. Evaluation of Vegetation Indices and a Modified Simple Ratio for Boreal Applications. Can. J. Remote Sens. 2014, 22, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, N.S.; Qin, W. Influences of canopy architecture on relationships between various vegetation indices and LAI and Fpar: A computer simulation. Remote Sens. Rev. 1994, 10, 309–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Viña, A.; Ciganda, V.; Rundquist, D.C.; Arkebauer, T.J. Remote estimation of canopy chlorophyll content in crops–art. no. L08403. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datt, B. Remote Sensing of Water Content in Eucalyptus Leaves. Aust. J. Bot. 1999, 47, 909–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, E.M.; Clarke, T.R.; Richards, S.E.; Colaizzi, P.D.; Thompson, T. Coincident detection of crop water stress, nitrogen status, and canopy density using ground based multispectral data. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Precision Agriculture, Bloomington, MN, USA, 16–19 July 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.M.; Huang, J.F.; Tang, Y.L.; Wang, X.Z. New Vegetation Index and Its Application in Estimating Leaf Area Index of Rice. Rice Sci. 2007, 14, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Gritz, Y.; Merzlyak, M.N. Relationships between leaf chlorophyll content and spectral reflectance and algorithms for non-destructive chlorophyll assessment in higher plant leaves. Plant Physiol. 2003, 160, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N.R.; Garg, P.K.; Ghosh, S.K.; Dadhwal, V.K. Estimation of leaf total chlorophyll and nitrogen concentrations using hyperspectral satellite imagery. J. Agric. Sci. 2008, 146, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.Y.; Huete, A.R.; Didan, K.; Miura, T. Development of a two-band enhanced vegetation index without a blue band. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 3833–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penuelas, J.; Gamon, J.A.; Fredeen, A.L.; Merino, J.; Field, C.B. Reflectance Indexes Associated with Physiological-Changes in Nitrogen-Limited and Water-Limited Sunflower Leaves. Remote Sens. Environ. 1994, 48, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleicher, T.D.; Bausch, W.C.; Delgado, J.A.; Ayers, P.D. Evaluation and Refinement of the Nitrogen Reflectance Index (NRI) for Site-Specific Fertilizer Management. In Proceedings of the 2001 ASAE Annual Meeting, Sacramento, CA, USA, 30 July–1 August 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Merzlyak, M.N.; Chivkunova, O.B. Optical properties and nondestructive estimation of anthocyanin content in plant leaves. Photochem. Photobiol. 2001, 74, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, D.A.; Gamon, J.A. Relationships between leaf pigment content and spectral reflectance across a wide range of species, leaf structures and developmental stages. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 81, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, J.; Curran, P.J. The MERIS terrestrial chlorophyll index. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2004, 25, 5403–5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broge, N.H.; Leblanc, E. Comparing prediction power and stability of broadband and hyperspectral vegetation indices for estimation of green leaf area index and canopy chlorophyll density. Remote Sens. Environ. 2001, 76, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.H.; Yin, G.D.; Sun, H.Y.; Wang, H.X.; Chen, S.Z.; Senthilnath, J.; Wang, J.Z.; Fu, Y.S. Scaling Effects on Chlorophyll Content Estimations with RGB Camera Mounted on a UAV Platform Using Machine-Learning Methods. Sensors 2020, 20, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shigeto, K.; Makoto, N. An Algorithm for Estimating Chlorophyll Content in Leaves Using a Video Camera. Ann. Bot. 1997, 81, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, G.E.; Neto, J.C. Verification of color vegetation indices for automated crop imaging applications. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2008, 63, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmi, W.; Garcia-Ruiz, F.J.; Nielsen, J.; Rasmussen, J.; Andersen, H.J. Detecting creeping thistle in sugar beet fields using vegetation indices. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2015, 112, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberioon, M.M.; Amin, M.S.M.; Anuar, A.R.; Gholizadeh, A.; Wayayok, A.; Khairunniza-Bejo, S. Assessment of rice leaf chlorophyll content using visible bands at different growth stages at both the leaf and canopy scale. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2014, 32, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guijarro, M.; Pajares, G.; Riomoros, I.; Herrera, P.J.; Burgos-Artizzu, X.P.; Ribeiro, A. Automatic segmentation of relevant textures in agricultural images. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2011, 75, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, J.C. A Combined Statistical-Soft Computing Approach for Classification and Mapping Weed Species in Minimum-Tillage Systems; The University of Nebraska-Lincoln: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sulik, J.J.; Long, D.S. Spectral considerations for modeling yield of canola. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 184, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Stark, R.; Rundquist, D. Novel algorithms for remote estimation of vegetation fraction. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 80, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh, A.; Saberioon, M.; Rossel, R.A.V.; Boruvka, L.; Klement, A. Spectroscopic measurements and imaging of soil colour for field scale estimation of soil organic carbon. Geoderma 2020, 357, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Fang, S.H.; Peng, Y.; Gong, Y.; Zhu, R.S.; Wu, X.T.; Ma, Y.; Duan, B.; Liu, J. UAV-Based Biomass Estimation for Rice-Combining Spectral, TIN-Based Structural and Meteorological Features. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, T.; Kaneko, T.; Okamoto, H.; Terawaki, M.; Hata, S. Development of Crop Growth Mapping System Using Machine Vision (Part 2). J. Jpn. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2005, 67, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendig, J.; Yu, K.; Aasen, H.; Bolten, A.; Bennertz, S.; Broscheit, J.; Gnyp, M.L.; Bareth, G. Combining UAV-based plant height from crop surface models, visible, and near infrared vegetation indices for biomass monitoring in barley. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2015, 39, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.H.; Chen, S.Z.; Wu, Z.F.; Wang, S.X.; Bryant, C.R.; Senthilnath, J.; Cunha, M.; Fu, Y.S.H. Integrating Spectral and Textural Information for Monitoring the Growth of Pear Trees Using Optical Images from the UAV Platform. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, V.; Torrent, J. Use of the Kubelka—Munk theory to study the influence of iron oxides on soil colour. J. Soil Sci. 1986, 37, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Acronym | Feature Type | Feature Number |

|---|---|---|

| Ref | Spectral reflectance | 462 |

| VIS | Vegetation indices | 33 |

| HSI_CT | Color and texture features of hyperspectral images | 73 |

| RGB_CT | Color and texture features of RGB images | 37 |

| Leaf Traits | Pretreatments | Preprocessing Results (R2) | Feature Selection | Feature Selection Results (R2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPAD | SG-PLSR | 0.8572 | CARS-PLSR | 0.8676 |

| LNC | MSC-PLSR | 0.6700 | CARS-PLSR | 0.7132 |

| LKC | SNV-PLSR | 0.7127 | CARS-BRR | 0.7358 |

| FWC | MSC-PLSR | 0.8611 | CARS-BRR | 0.8803 |

| DWC | MA-PLSR | 0.8819 | LASSO-PLSR | 0.8724 |

| Leaf Traits | VIS | HSI-Tex | HSI-Col | RGB-Tex | RGB-Col |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPAD | 33 | 35 | 21 | 7 | 23 |

| LNC | 15 | 26 | 4 | 7 | 4 |

| LKC | 28 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 18 |

| FWC | 26 | 36 | 4 | 7 | 23 |

| DWC | 26 | 37 | 4 | 7 | 22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jiang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Li, K.; Wu, Z.; Su, Y.; He, K.; Fang, Y.; Sun, X.; Liu, W. Construction of a Prediction Model for Functional Traits of Grape Leaves Based on Multi-Stage Collaborative Optimization. Agronomy 2026, 16, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010029

Jiang Q, Zhou X, Li K, Wu Z, Su Y, He K, Fang Y, Sun X, Liu W. Construction of a Prediction Model for Functional Traits of Grape Leaves Based on Multi-Stage Collaborative Optimization. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Qingling, Xuejian Zhou, Kai Li, Zehao Wu, Yuan Su, Ke He, Yulin Fang, Xiangyu Sun, and Wenzheng Liu. 2026. "Construction of a Prediction Model for Functional Traits of Grape Leaves Based on Multi-Stage Collaborative Optimization" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010029

APA StyleJiang, Q., Zhou, X., Li, K., Wu, Z., Su, Y., He, K., Fang, Y., Sun, X., & Liu, W. (2026). Construction of a Prediction Model for Functional Traits of Grape Leaves Based on Multi-Stage Collaborative Optimization. Agronomy, 16(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010029