Effects of Stocking Densities on Mud Crab Production and Microbial Community Dynamics in the Integrated Saline Tolerant Rice–Mud Crab (Scylla paramamosain) System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Rice Paddy Modification and Subdivision

2.2. Desalination and Seedling Release of Mud Crabs

2.3. Daily Management of Mud Crabs

2.4. Measurement of Growth Parameters of Mud Crabs

2.5. Analysis of Environmental Physicochemical Indicators

2.6. Microbial Sampling Methods

2.7. DNA Extraction and Illumina Sequencing

2.8. Functional Gene Chip Sampling Methods

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

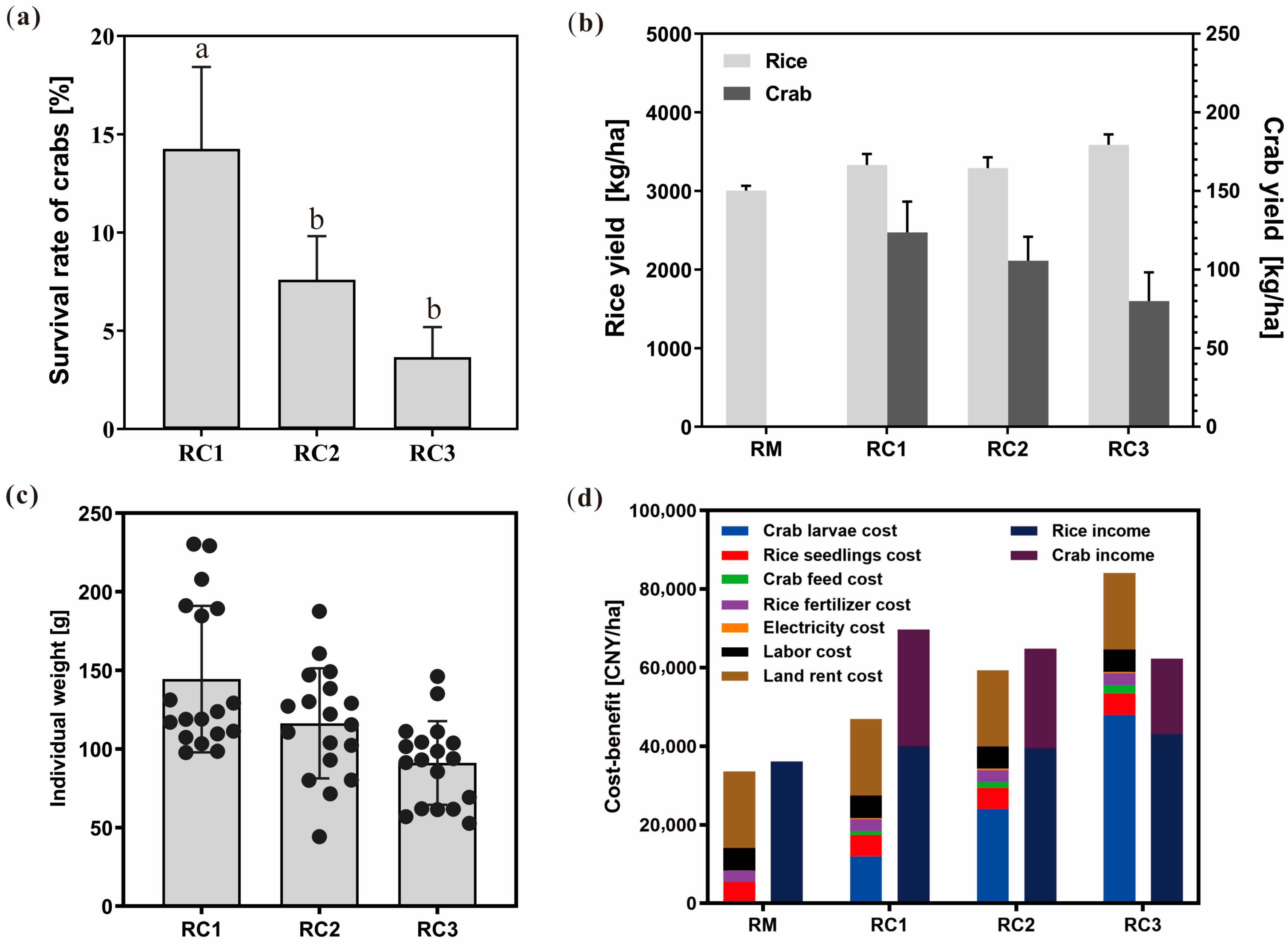

3.1. Impact of the SARC System on Rice and Crab Yield, and Economic Performance

3.2. Influence of the SARC System on Water Quality and Soil Nutrients

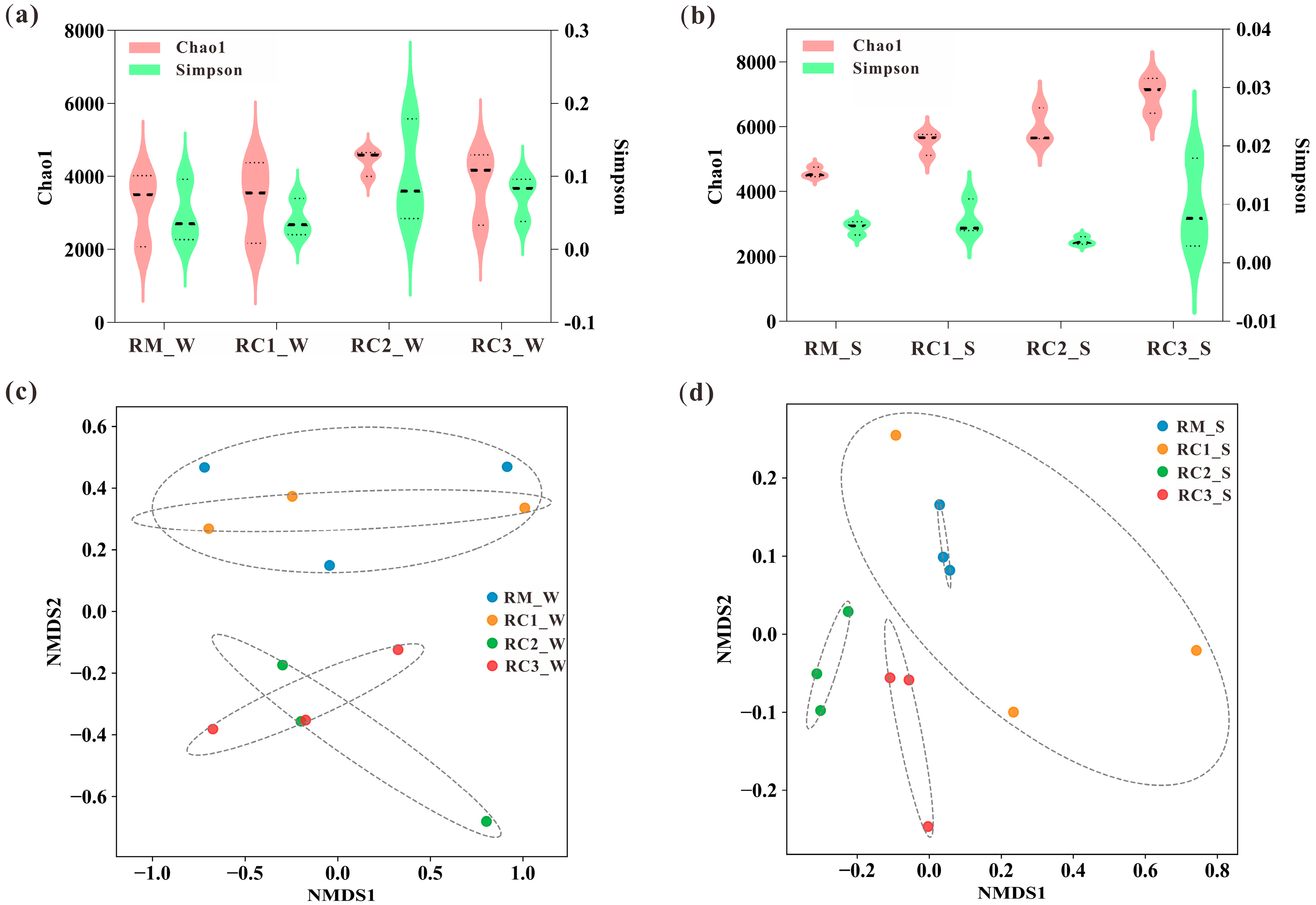

3.3. Dynamics of Water and Soil Microbial Communities in the SARC System

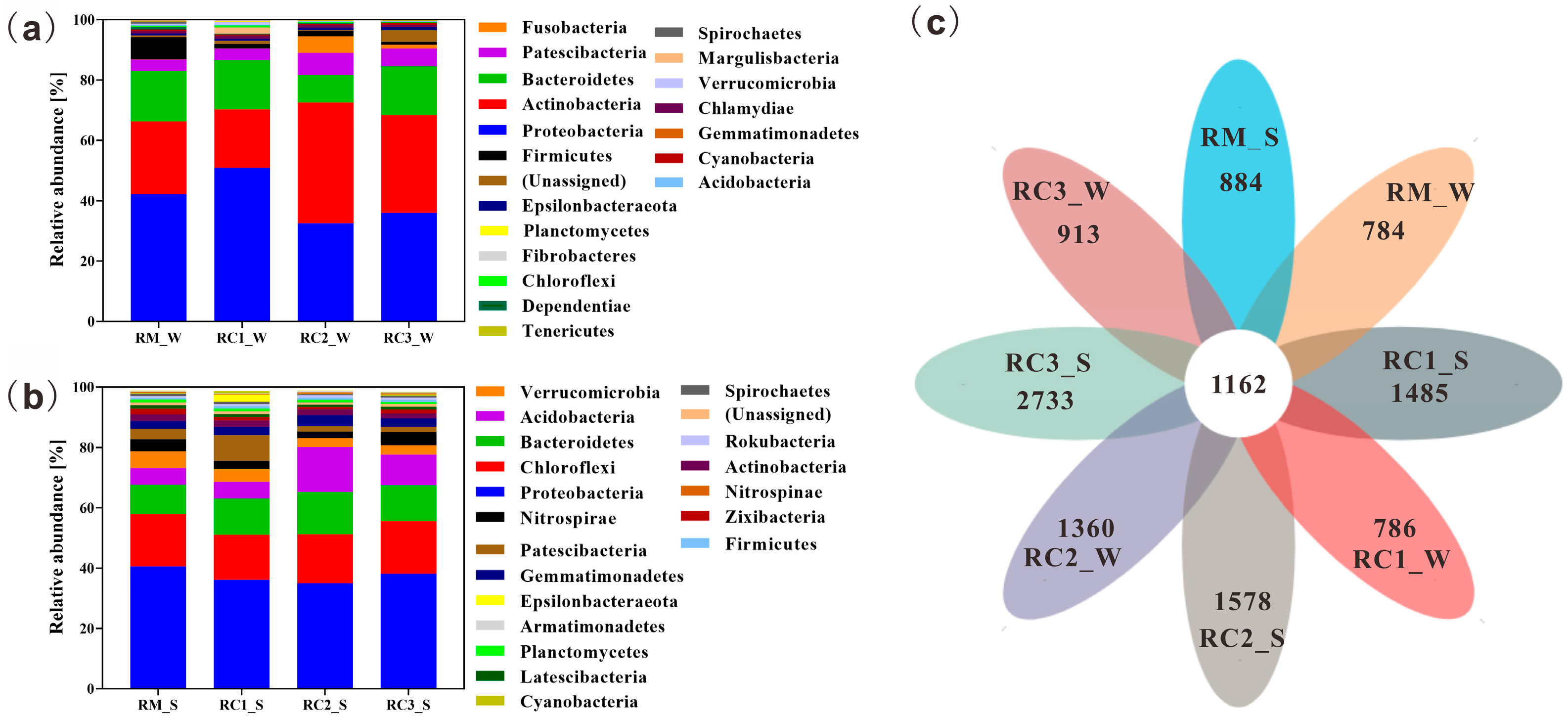

3.4. Microbial Community Composition and Structure in the SARC System

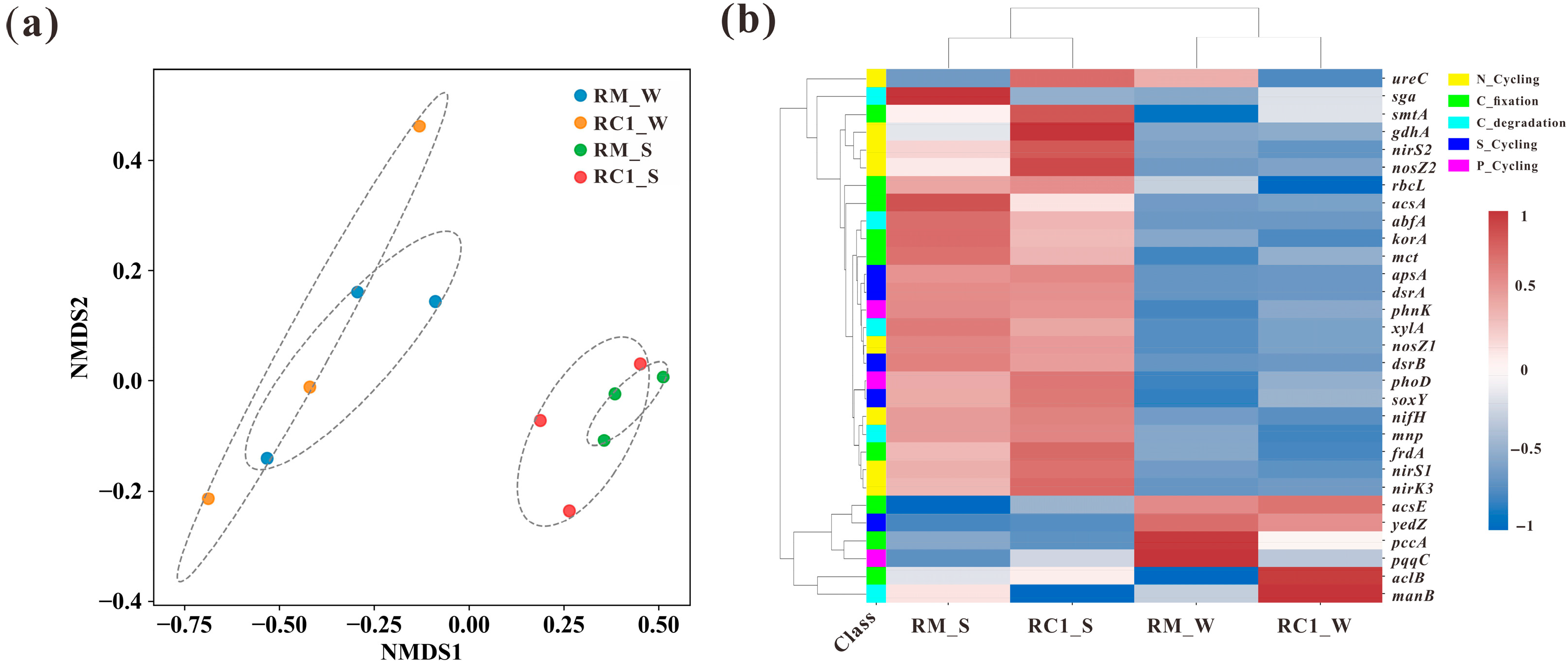

3.5. Microbial Functional Genes of C/N/S/P in the SACRC System

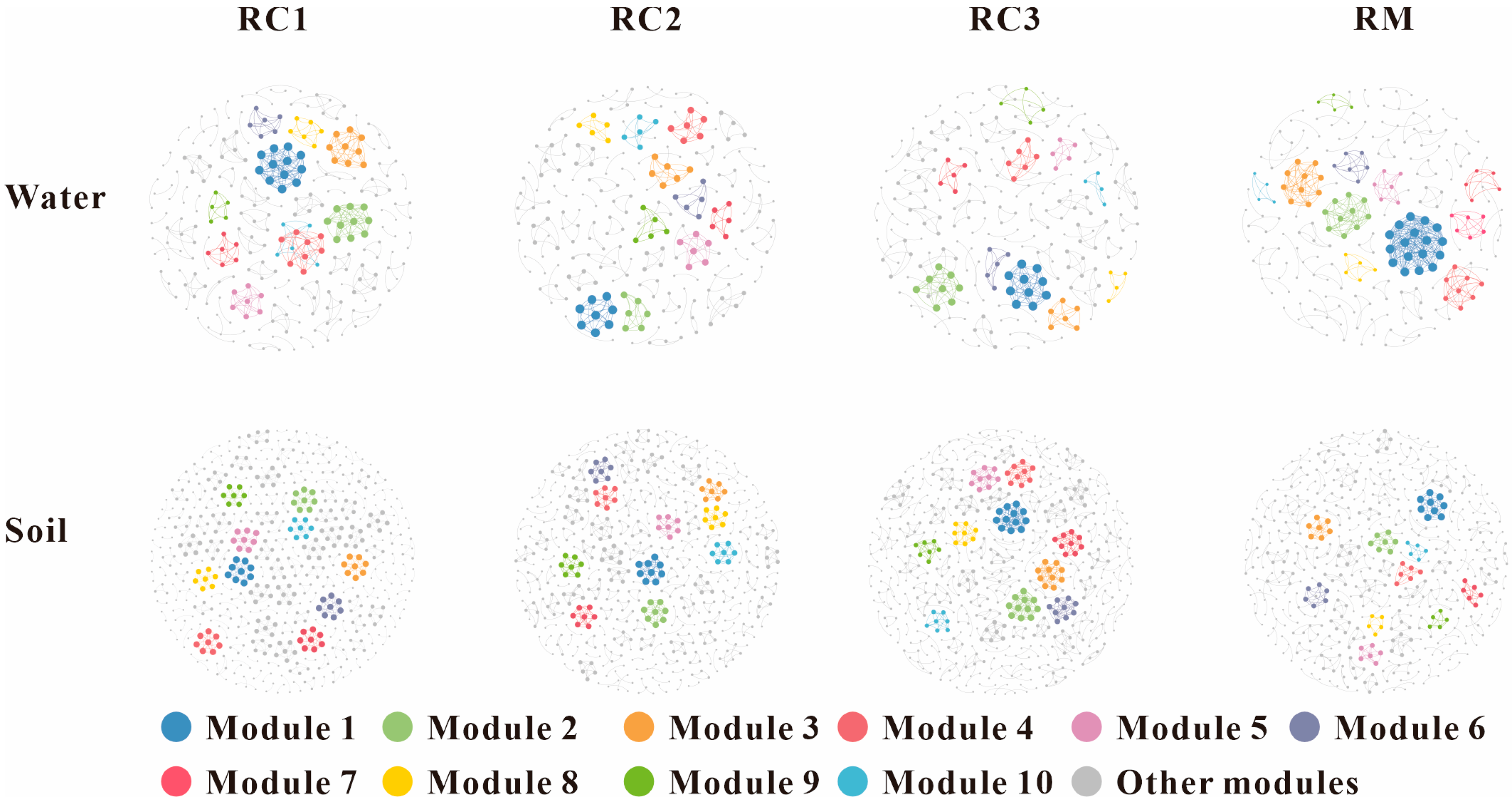

3.6. Co-Occurrence Network

4. Discussion

4.1. Suitable Stocking Density Can Significantly Improve the Comprehensive Economic Efficiency of the SARC System

4.2. The SARC System Changes the Physicochemical Properties of Paddy Water and Soil

4.3. SARC Altered the Microbial Community Composition and Structure of Paddy Water

4.4. SARC Altered the Functional Gene Abundance and Structure

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SARC | The Salinity-tolerant Rice–Mud Crab Co-culture |

| NMDS | Non-metric multidimensional scaling |

| COD | Chemical oxygen demand |

References

- Xia, L.; Li, X.; Ma, Q.; Lam, S.K.; Wolf, B.; Kiese, R.; Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Chen, D.; Li, Z.; Yan, X. Simultaneous quantification of N2, NH3 and N2O emissions from a flooded paddy field under different N fertilization regimes. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 2292–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Anderson, W.; Yang, P.; Wu, W.; Tang, H.; You, L. Chinese rice production area adaptations to climate changes, 1949–2010. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 2032–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C.; Zhang, T. Eutrophication in a Chinese context: Understanding various physical and socio-economic aspects. Ambio 2010, 39, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wesenbeeck, C.F.A.; Keyzer, M.A.; van Veen, W.C.M.; Qiu, H. Can China’s overuse of fertilizer be reduced without threatening food security and farm incomes? Agric. Syst. 2021, 190, 103093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, C.; Gianuca, A.T.; Schweiger, O.; Franzén, M.; Settele, J. Pesticides and land cover heterogeneity affect functional group and taxonomic diversity of arthropods in rice agroecosystems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 297, 106927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, M.; Becker, K. Integrated rice-fish culture: Coupled production saves resources. Nat. Resour. Forum. 2005, 29, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.; De Silva, S. Finfish cage culture in Asia: An overview of status, lessons learned and future developments. In Proceedings of the FAO Regional Technical Expert Workshop on Cage Culture in Africa, Entebbe, Uganda, 20–23 October 2004; pp. 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wheatcroft, R.A. Time-series measurements of macrobenthos abundance and sediment bioturbation intensity on a flood-dominated shelf. Prog. Oceanogr. 2006, 71, 88–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Hao, X.; Dang, Z.; Yang, L. Development report on integrated rice-fish farming industry in China (2022). Chin. Fish. 2023, 1, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, H.; Li, Y.; Huang, R. Advances and challenges in the breeding of salt-tolerant rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurdiani, R.; Zeng, C. Effects of temperature and salinity on the survival and development of mud crab, Scylla serrata (Forsskål), larvae. Aquacult. Res. 2007, 38, 1529–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, J.; Wong, T.M. Responses of adult mud crabs (Scylla serrata) (Forskal) to salinity and low oxygen tension. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Physiol. 1987, 86, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Shi, X.; Fang, S.; Xie, Z.; Guan, M.; Li, S.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ikhwanuddin, M.; Ma, H. Different biochemical composition and nutritional value attribute to salinity and rearing period in male and female mud crab Scylla paramamosain. Aquaculture 2019, 513, 734417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refaey, M.M.; Li, D.; Tian, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Tang, R. High stocking density alters growth performance, blood biochemistry, intestinal histology, and muscle quality of channel catfish Ictalurus punctatus. Aquaculture 2018, 492, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, H. Rice monoculture and integrated rice-fish farming in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam—Economic and ecological considerations. Ecol. Econ. 2002, 41, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wu, G.; Li, Y.; Hu, C.; Ge, L.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Bai, N.; et al. Long-term rice-crayfish-turtle co-culture maintains high crop yields by improving soil health and increasing soil microbial community stability. Geoderma 2022, 413, 115745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, K.; Mander, Ü.; Öpik, M.; Sepp, S.; Kanger, K.; Schindler, T.; Soosaar, K.; Pihlatie, M.; Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Putkinen, A.; et al. Temporal and spatial dynamics of microbial communities and greenhouse gas flux responses to experimental flooding in riparian forest soils. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2025, 101, fiaf109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Jiang, A.; Kong, Z.; Lv, X.; Zhang, J.; Wu, J.; Zhou, C.; Tan, Z. Multi-omics analysis reveals the mechanism of rosemary extract supplementation in increasing milk production in Sanhe dairy cows via the “rumen-serum-milk” metabolic pathway. Anim. Nutr. 2025, 23, 396–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Zhang, C.; Qin, B.; Yang, T.; Xu, R.; Zhu, L.; Han, G.; Wu, L.; Li, S.; Bi, J.; et al. Microbial mechanisms of biochar reducing methane emission in a rice-crayfish integrated system. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 395, 127790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jia, Q.; Sun, D.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, H.; Chen, Y. Influence of nitrogen substitution at an equivalent total nitrogen level on bacterial and fungal communities, as well as enzyme activities of the ditch bottom soil in a rice-fish coculture system. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 4206–4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, H.; Wang, H.; Tang, L.; Li, X.; Wang, C.; Mu, C.; Shi, C. A Method for Effectively Improving the Survival Rate of Juvenile Eriocheir Sinensis During Desalination. CN110463638A, 19 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, M.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, L.; Hua, J.; Rong, H.; Gu, Z. In- situ and ex- situ purification effect of ecological ponds of Euryale ferox Salisb on shrimp aquaculture. Aquaculture 2021, 540, 736678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S. Soil Agrochemical Analysis, 3rd ed.; China Agricultural Press: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Song, G.; Sun, B.; Jiao, J. Comparison of ultraviolet spectrophotometry method for determination of soil nitrate nitrogen with other methods. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2007, 44, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, D.; Li, Y.; Yao, H.; Chapman, S.J. Effects of different carbon sources on methane production and the methanogenic communities in iron rich flooded paddy soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 823, 153636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, K.; Huang, L.; Dong, P.; Wang, S.; Chen, H.; Lu, Z.; Hou, D.; Zhang, D. Fine-scale succession patterns and assembly mechanisms of bacterial community of Litopenaeus vannamei larvae across the developmental cycle. Microbiome 2020, 8, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, M.; Liu, W.; Xu, J.; Li, Y. Comparative evaluation of 16S rRNA primer pairs in identifying nitrifying guilds in soils under long-term organic fertilization and water management. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1424795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zheng, B.; Su, J.; Li, H.; Yao, H. High-Throughput Detection Primers and Detection Methods for Microbial Carbon, Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Sulfur Element Functional Genes. CN106048041B, 26 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lisboa, V.; Barcarolli, I.F.; Sampaio, L.; Bianchini, A. Effect of salinity on survival, growth and biochemical parameters in juvenile Lebranch mullet Mugil liza (Perciformes: Mugilidae). Neotrop. Ichthyol. 2015, 13, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imsland, A.K.D.; Roth, B.; Fjelldal, P.G.; Stefansson, S.O.; Handeland, S.; Mikalsen, B. The effect of continuous light at low temperatures on growth in Atlantic salmon reared in commercial size sea pens. Aquaculture 2017, 479, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Liu, X.; Geng, D.; Xu, X.; Li, Y. Effect of crab stocking density on cultivation efficiency in paddy crab aquaculture. Hunan Agric. Sci. 2019, 8, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammouth, S.; d’Orbcastel, E.R.; Gasset, E.; Lemarié, G.; Breuil, G.; Marino, G.; Coeurdacier, J.; Fivelstad, S.; Blancheton, J. The effect of density on sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) performance in a tank-based recirculating system. Aquacult. Eng. 2009, 40, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, D.C.; Silva, P.I.M.; Larsen, B.K.; Höglund, E. High oxygen consumption rates and scale loss indicate elevated aggressive behaviour at low rearing density, while elevated brain serotonergic activity suggests chronic stress at high rearing densities in farmed rainbow trout. Physiol. Behav. 2013, 122, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, M.; Keyvanshokooh, S.; Salati, A.P.; Ghaedi, A. Effects of chronic high stocking density on liver proteome of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 43, 1373–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Dong, S.; Lei, Y.; Li, Y. The effect of stocking density of Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis on rice and crab seed yields in rice–crab culture systems. Aquaculture 2007, 273, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vromant, N.; Chau, N.T.H. Overall effect of rice biomass and fish on the aquatic ecology of experimental rice plots. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2005, 111, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halwart, M.; Litsinger, J.; Barrion, A.; Viray, M.; Kaule, G. Efficacy of Common Carp and Nile Tilapia as biocontrol agents of rice insect pests in the Philippines. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2012, 58, 330–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightfoot, C.; van Dam, A.; Costa-Pierce, B. What’s Happening to the Rice Yields in Rice-Fish Systems. In Rice-Fish Research and Development in Asia; International Center for Living Aquatic Resources Management: Manila, Philippines, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, K.R.; Wasielesky, W.; Abreu, P.C. Nitrogen and phosphorus dynamics in the biofloc production of the pacific white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei. J. World Aquacult. Soc. 2013, 44, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, D.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Wan, L.; Song, C.; Zhou, Y.; Cao, X. Nitrogen and phosphorus turnover and coupling in ponds with different aquaculture species. Aquaculture 2023, 563, 738997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.; Preston, N.; Thompson, P.J.; Burford, M. Nitrogen budget and effluent nitrogen components at an intensive shrimp farm. Aquaculture 2003, 218, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Huang, S.; Cao, C.; Cai, M.; Zhai, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, F. Effects of nitrogen fertilizer management on dynamics of nitrogen in rice field surface water and nitrogen absorption utilization efficiency. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2010, 29, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Li, S.; Wu, Q.; Zhu, X.; Wu, J. Effects of different fertilization treatments on nitrogen runoff and leaching losses in paddy fields. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2016, 30, 23–28+33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balvanera, P.; Pfisterer, A.B.; Buchmann, N.; He, J.; Nakashizuka, T.; Raffaelli, D.; Schmid, B. Quantifying the evidence for biodiversity effects on ecosystem functioning and services. Ecol. Lett. 2006, 9, 1146–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkowski, P.G.; Fenchel, T.; Delong, E.F. The Microbial Engines That Drive Earth’s Biogeochemical Cycles. Science 2008, 320, 1034–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, B.S.; Philippot, L. Insights into the resistance and resilience of the soil microbial community. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 37, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xun, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Ren, Y.; Xiong, W.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, N.; Miao, Y.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, R. Specialized metabolic functions of keystone taxa sustain soil microbiome stability. Microbiome 2021, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Wang, W.; Yao, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Niu, B. Microbial interactions within beneficial consortia promote soil health. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 900, 165801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, D.; Xing, C.; Hou, D.; Zeng, S.; Zhou, R.; Yu, L.; Wang, H.; Deng, Z.; Weng, S.; He, J.; et al. Distinct bacterial communities in the environmental water, sediment and intestine between two crayfish-plant coculture ecosystems. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 5087–5101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdy, A.; Wandera, S.M.; Bi, S.; Song, Y.; Qiao, W.; Dong, R. Response of the microbial community to the methanogenic performance of biologically hydrolyzed sewage sludge with variable hydraulic retention times. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 288, 121581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemos, L.N.; Medeiros, J.D.; Dini-Andreote, F.; Fernandes, G.R.; Varani, A.M.; Oliveira, G.; Pylro, V.S. Genomic signatures and co-occurrence patterns of the ultra-small Saccharimonadia (phylum CPR/Patescibacteria) suggest a symbiotic lifestyle. Mol. Ecol. 2019, 28, 4259–4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.; Kristensen, J.M.; Herbold, C.W.; Pjevac, P.; Kitzinger, K.; Hausmann, B.; Dueholm, M.K.D.; Nielsen, P.H.; Wagner, M. Global abundance patterns, diversity, and ecology of Patescibacteria in wastewater treatment plants. Microbiome 2024, 12, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fang, L.; Liang, X.; Guo, W.; Lv, L.; Li, L. Influence of environmental factors and bacterial community diversity in pond water on health of Chinese perch through Gut Microbiota change. Aquac. Rep. 2021, 20, 100629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunfield, P.F.; Yuryev, A.; Senin, P.; Smirnova, A.V.; Stott, M.B.; Hou, S.; Ly, B.; Saw, J.H.; Zhou, Z.; Ren, Y.; et al. Methane oxidation by an extremely acidophilic bacterium of the phylum Verrucomicrobia. Nature 2007, 450, 879–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, S.L.; Daly, R.A.; Borton, M.A.; Solden, L.M.; Welch, S.A.; Cole, D.R.; Mouser, P.J.; Wilkins, M.J.; Wrighton, K.C. Genome-resolved metagenomics extends the environmental distribution of the Verrucomicrobia phylum to the deep terrestrial subsurface. mSphere 2019, 4, e00613-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ji, Y.; Guo, Y.; Yin, X.; Li, Y.; Han, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; et al. Responses of soil respiration and microbial community structure to fertilizer and irrigation regimes over 2 years in temperate vineyards in North China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 840, 156469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Dou, Y.; Yang, X.; An, S. Soil microbial community and their functional genes during grassland restoration. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gravuer, K.; Eskelinen, A.; Winbourne, J.B.; Harrison, S.P. Vulnerability and resistance in the spatial heterogeneity of soil microbial communities under resource additions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 7263–7270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunan, N.; Schmidt, H.; Raynaud, X. The ecology of heterogeneity: Soil bacterial communities and C dynamics. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2020, 375, 20190249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yu, H.; Yu, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zeng, J.; Chen, P.; Xiao, F.; He, Z.; Yan, Q. Ecological stability of microbial communities in Lake Donghu regulated by keystone taxa. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 136, 108695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lin, W.; Wu, Q.; Shi, C.; Wang, C.; Ye, Y. Bacterial dynamics and biotic sources in the developing swimming crab embryos. Aquaculture 2025, 595, 741523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.; Wu, L.; Deng, Y.; He, Z.; Van Nostrand, J.; Robertson, P.G.; Schmidt, T.M.; Zhou, J. Functional gene differences in soil microbial communities from conventional, low-input, and organic farmlands. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Wang, J.; Dippold, M.; Gao, Y.; Blagodatskaya, E.; Kuzyakov, Y. Biochar affects soil organic matter cycling and microbial functions but does not alter microbial community structure in a paddy soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 556, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, K.A.; Yarwood, S.A.; James, B.R. Soil urease activity and bacterial ureC gene copy numbers: Effect of pH. Geoderma 2017, 285, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, S. Diversity and Activity of Nitrogenase Nifh Genes of Endophytic Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria in Rice and Wheat; Chinese Academy Of Agricultural Sciences: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Xie, J.; Ni, J. Hydrological and soil physiochemical variables determine the rhizospheric microbiota in subtropical lakeshore areas. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; He, J.; Liu, G.; Ma, Y.; Ding, Y.; Zhou, H. Influence of salinity on the diversity of nitrogen-fixing microbial nifH genes in rice soil. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2022, 50, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W.; Xing, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Gao, N.; Ying, Y. Diverse responses of pqqC- and phoD-harbouring bacterial communities to variation in soil properties of Moso bamboo forests. Microb. Biotechnol. 2022, 15, 2097–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Lu, S. Straw and straw biochar differently affect phosphorus availability, enzyme activity and microbial functional genes in an Ultisol. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 805, 150325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochimsen, B.; Lolle, S.; McSorley, F.R.; Nabi, M.; Stougaard, J.; Zechel, D.L.; Hove-Jensen, B. Five phosphonate operon gene products as components of a multi-subunit complex of the carbon-phosphorus lyase pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 11393–11398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imhoff, J.F. New dimensions in microbial ecology-functional genes in studies to unravel the biodiversity and role of functional microbial groups in the environment. Microorganisms 2016, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Wang, S.; Qin, P.; Fan, S.; Su, X.; Cai, P.; Lu, J.; Cui, H.; Wang, M.; Shu, Y.; et al. Anaerobic thiosulfate oxidation by the Roseobacter group is prevalent in marine biofilms. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| COD (mg/L) | NH4+ (mg/L) | NO3− (mg/L) | NO2− (mg/L) | TN (mg/L) | PO43− (mg/L) | TP (mg/L) | S (mg/L) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RM_W | 20.667 ± 1.528 a | 0.047 ± 0.006 a | 0.107 ± 0.031 a | 0.002 ± 0.001 a | 1.667 ± 0.153 | 0.027 ± 0.006 a | 0.043 ± 0.015 a | ND |

| RC1_W | 36.667 ± 5.033 b | 0.23 ± 0.046 b | 0.213 ± 0.05 b | 0.006 ± 0.002 b | 2.133 ± 0.404 | 0.03 ± 0.01 a | 0.05 ± 0.026 ab | 0.007 ± 0.012 |

| RC2_W | 47.667 ± 3.512 c | 0.293 ± 0.025 bc | 0.41 ± 0.036 c | 0.012 ± 0.002 c | 1.9 ± 0.265 | 0.063 ± 0.015 b | 0.083 ± 0.015 bc | ND |

| RC3_W | 51.667 ± 4.163 c | 0.363 ± 0.05 c | 0.423 ± 0.015 c | 0.021 ± 0.003 d | 1.967 ± 0.603 | 0.08 ± 0.02 b | 0.103 ± 0.012 c | ND |

| pH | NO2− (mg/kg) | NH4+ (mg/kg) | TN (mg/kg) | AP (mg/kg) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RM_S | 7.23 ± 0.09 b | 2.837 ± 0.103 a | 10.79 ± 0.92 a | 1.507 ± 0.081 | 9.203 ± 0.786 a |

| RC1_S | 7.083 ± 0.04 a | 2.88 ± 0.176 a | 13.52 ± 0.93 ab | 1.483 ± 0.049 | 12.333 ± 0.847 b |

| RC2_S | 7.153 ± 0.038 ab | 3.347 ± 0.156 b | 15.43 ± 1.28 bc | 1.493 ± 0.96 | 14.54 ± 1.201 bc |

| RC3_S | 7.147 ± 0.06 ab | 3.54 ± 0.066 b | 16.78 ± 2.35 c | 1.46 ± 0.104 | 16.17 ± 2.262 c |

| Functional Areas | RM_W | RC1_W | RC2_W | RC3_W | RM_S | RC1_S | RC2_S | RC3_S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nodes | 224 | 264 | 229 | 240 | 520 | 590 | 559 | 567 |

| Edge | 437 | 455 | 288 | 317 | 569 | 850 | 708 | 910 |

| Average degree | 3.902 | 3.447 | 2.515 | 2.642 | 2.188 | 2.881 | 2.553 | 3.21 |

| Modularity | 0.871 | 0.948 | 0.968 | 0.957 | 0.985 | 0.984 | 0.984 | 0.976 |

| Percentage of negative correlations | 7.55 | 11.43 | 17.36 | 19.24 | 46.05 | 30 | 42.8 | 34.84 |

| Percentage of positive correlations | 92.45 | 88.57 | 82.64 | 80.76 | 53.95 | 70 | 57.2 | 65.16 |

| Graph density | 0.017 | 0.013 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.006 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zheng, C.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, F.; Xia, J.; Wang, X.; Yao, Z.; Wang, C.; Mu, C.; Ye, Y.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Effects of Stocking Densities on Mud Crab Production and Microbial Community Dynamics in the Integrated Saline Tolerant Rice–Mud Crab (Scylla paramamosain) System. Agronomy 2026, 16, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010027

Zheng C, Zhou H, Zhang F, Xia J, Wang X, Yao Z, Wang C, Mu C, Ye Y, Zhou Y, et al. Effects of Stocking Densities on Mud Crab Production and Microbial Community Dynamics in the Integrated Saline Tolerant Rice–Mud Crab (Scylla paramamosain) System. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010027

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Chunchun, Houjie Zhou, Feifei Zhang, Jingjing Xia, Xiaopeng Wang, Zhiyuan Yao, Chunlin Wang, Changkao Mu, Yangfang Ye, Yueyue Zhou, and et al. 2026. "Effects of Stocking Densities on Mud Crab Production and Microbial Community Dynamics in the Integrated Saline Tolerant Rice–Mud Crab (Scylla paramamosain) System" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010027

APA StyleZheng, C., Zhou, H., Zhang, F., Xia, J., Wang, X., Yao, Z., Wang, C., Mu, C., Ye, Y., Zhou, Y., Wu, Q., & Shi, C. (2026). Effects of Stocking Densities on Mud Crab Production and Microbial Community Dynamics in the Integrated Saline Tolerant Rice–Mud Crab (Scylla paramamosain) System. Agronomy, 16(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010027