Post-Silking Nitrogen Topdressing Optimizes Nitrogen Accumulation and Enhances Yield in Densely Planted Maize

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

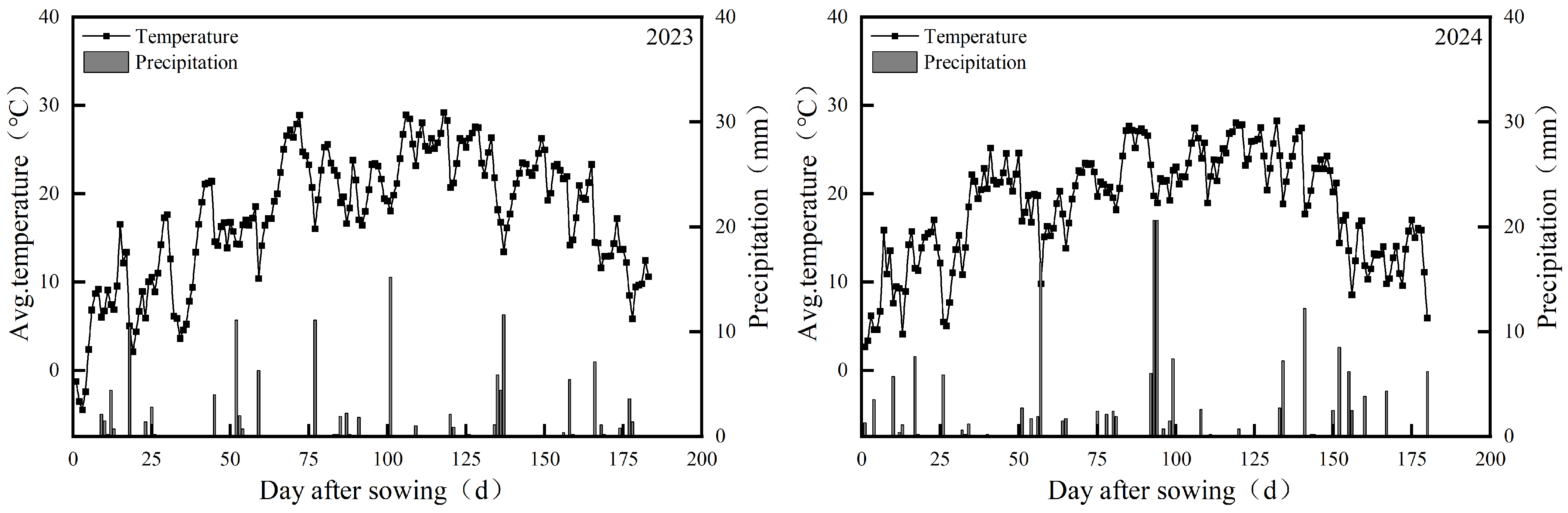

2.1. Experimental Site

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Sampling and Measurements

2.3.1. Key Phenological Stage Recording

2.3.2. Determination of Plant Nitrogen Content

2.3.3. Yield Determination

2.3.4. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Yield and Yield Components

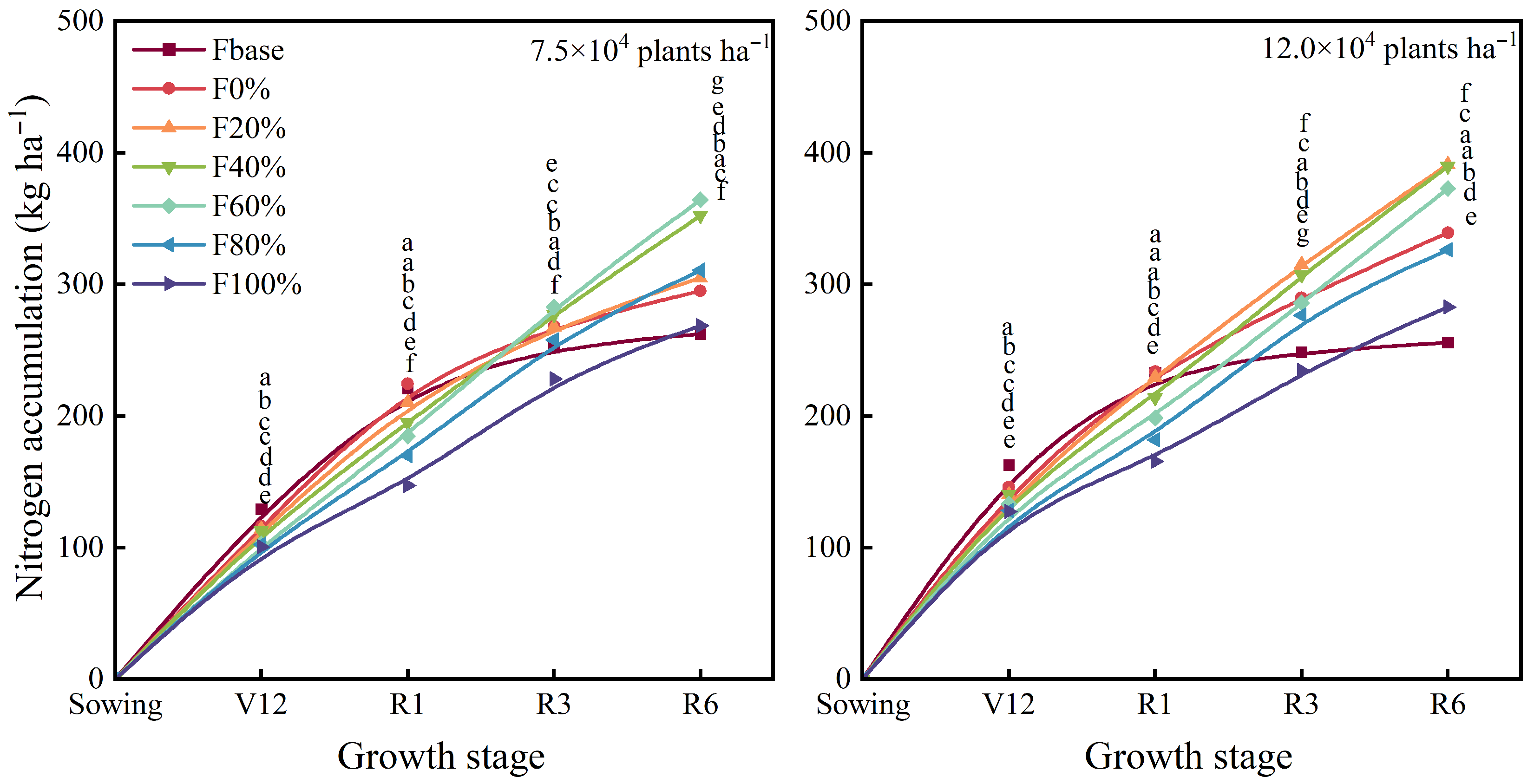

3.2. Effects of Post-Silking Nitrogen Topdressing on Nitrogen Accumulation in Maize

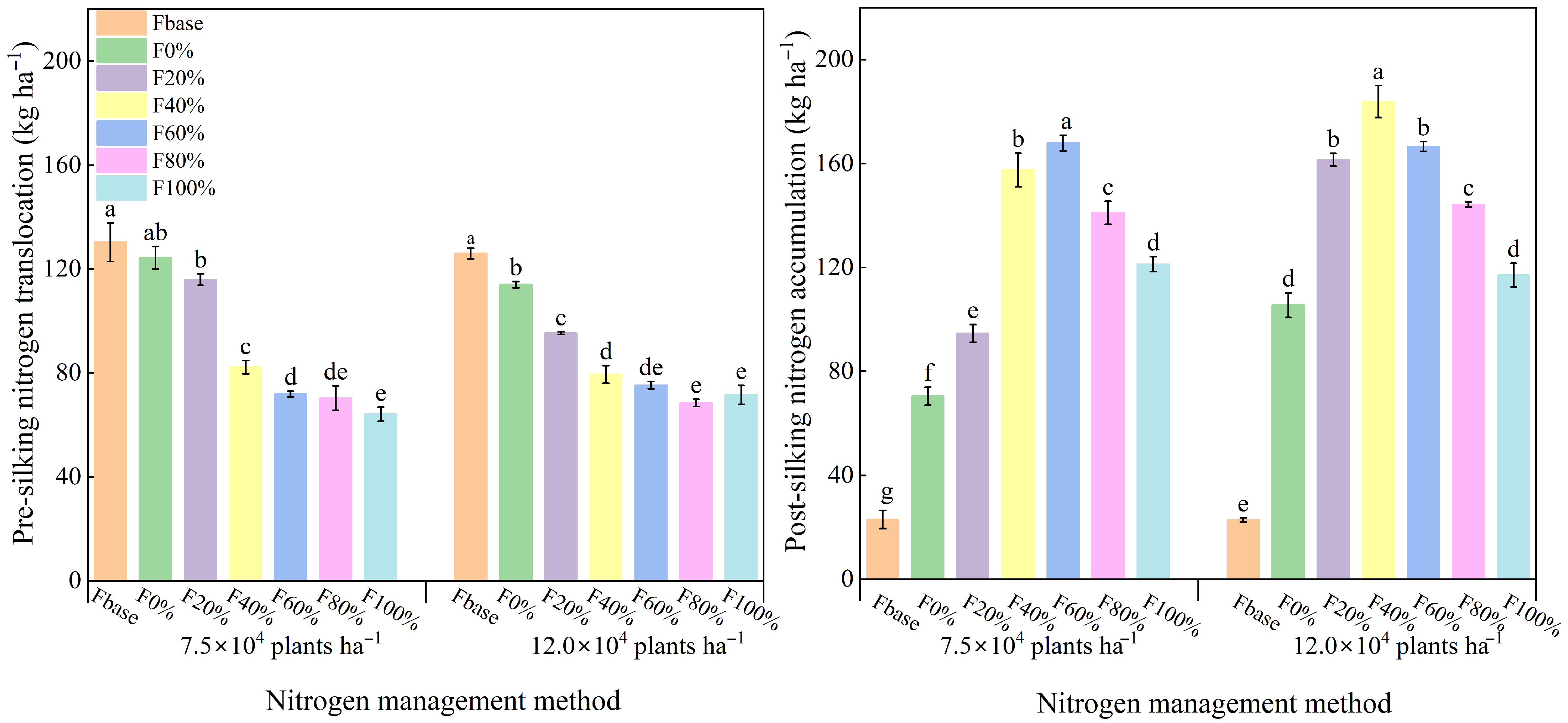

3.3. Effects of Post-Silking Nitrogen Topdressing on Nitrogen Translocation in Maize

3.4. Effects of Post-Silking Nitrogen Topdressing on Nitrogen Use Efficiency

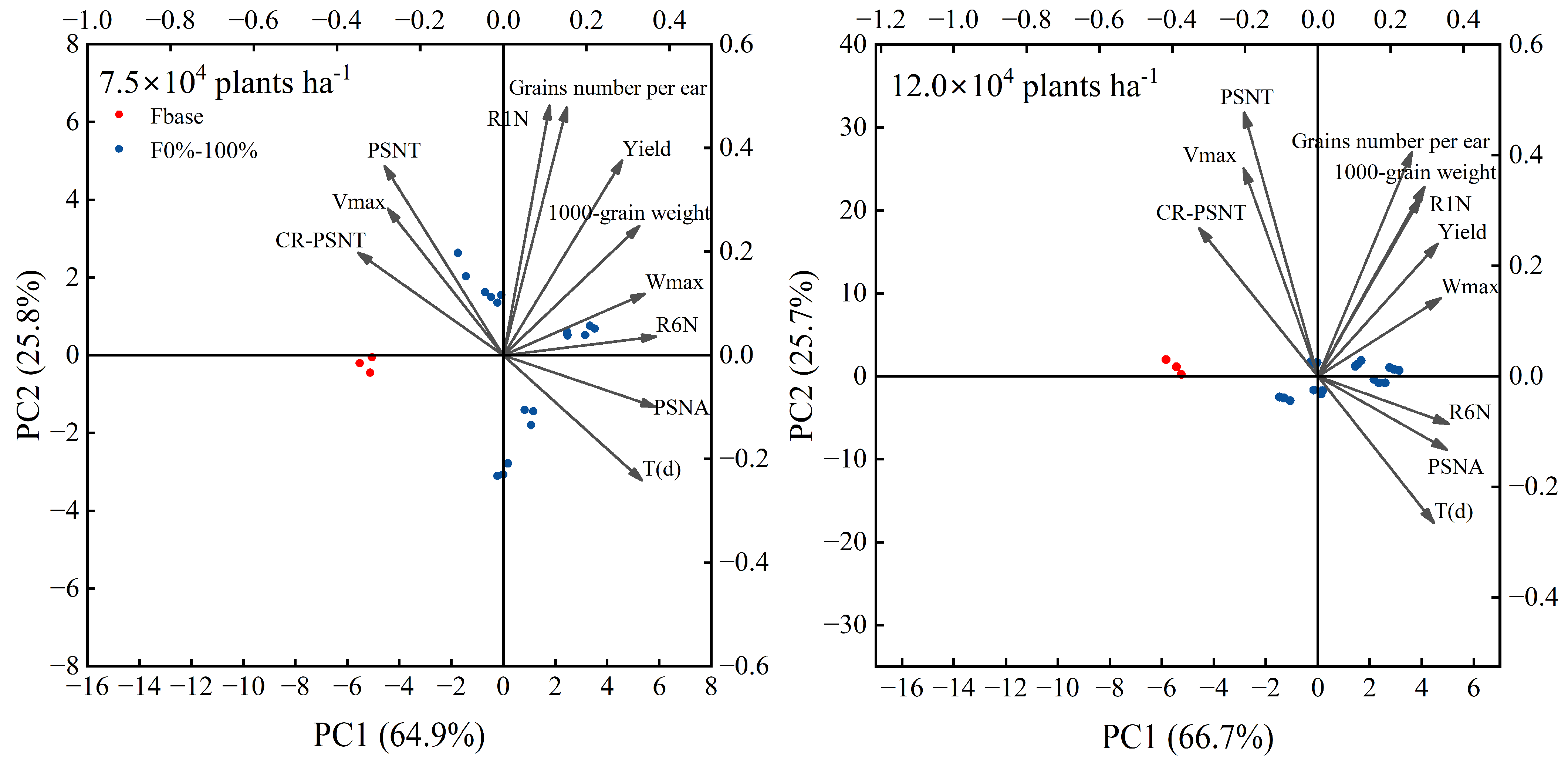

3.5. Principal Component Analysis of Yield and Related Parameters Under Different Post-Silking Nitrogen Proportions

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Fertilization Methods on Maize Yield

4.2. Effects of Fertilization Methods on Nitrogen Accumulation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stagnari, F.; Maggio, A.; Galieni, A.; Pisante, M. Multiple benefits of legumes for agriculture sustainability: An overview. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2017, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccarthy, U.; Uysal, I.; Badia, M.R.; Mercier, S.; Donnell, C.O.; Ktenioudaki, A. Global food security-issues, challenges and technological solutions. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 77, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.F.; Ma, L.; Huang, G.Q.; Wu, L.; Chen, X.P.; Zhang, F.S. The development and contribution of nitrogenous fertilizer in China and challenges faced by the country. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2013, 46, 3161–3171. [Google Scholar]

- Greveniotis, V.; Zotis, S.; Sioki, E.; Ipsilandis, C. Field population density effects on field yield and morphological characteristics of maize. Agriculture 2019, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.Q.; Lian, X.R.; Liu, Z.X.; Zhou, Y.Q.; Zhao, X.Q. Research progress on the mechanism of controlling maize plant height and ear height. Mol. Plant Breed. 2021, 19, 7965–7976. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.K.; Zhao, J.R.; Dong, S.T.; Zhao, M.; Li, C.H.; Cui, Y.H.; Liu, Y.H.; Gao, J.L.; Xue, J.Q.; Wang, L.C.; et al. Advances and prospects of maize cultivation in China. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2017, 50, 1941–1959. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.T.; Li, R.F.; Wang, K.R.; Xie, R.Z.; Hou, P.; Ming, B.; Xue, J.; Zhang, G.Q.; Liu, G.Z.; Li, S.K. Creation and thinking of China’s spring maize high-yield record. J. Maize Sci. 2021, 29, 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.B.; Qu, X.Y.; Yu, N.N.; Ren, B.Z.; Liu, P.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, J.W. Effects of nitrogen application rate on grain filling characteristics and endogenous hormones in summer maize. Acta Agron. Sin. 2022, 48, 2366–2376. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, S.; Khan, A.; Ashraf, U.; Liu, H.H.; Li, J.C. Characterization of the Effect of Increased Plant Density on Canopy Morphology and Stalk Lodging Risk. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asibi, A.E.; Chai, Q.; Coulter, J.A. Mechanisms of Nitrogen Use in Maize. Agronomy 2019, 9, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Z.X.; Huo, Z.J.; Liu, P.; Dong, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, B. Modified fertilization management of summer maize (Zea mays L.) in northern China improves grain yield and efficiency of nitrogen use. J. Integr. Agric. 2016, 14, 1644–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.J.; Lü, T.F.; Zhao, J.R.; Wang, R.H.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, W.T.; Liu, Y.E.; Liu, X.Z.; Chen, C.Y.; Xing, J.F.; et al. Grain filling characteristics of summer maize varieties under different sowing dates in the Huang-Huai-Hai region. Acta Agron. Sin. 2021, 47, 566–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.W.; Wang, J.Q.; Li, C.J.; Liu, S.P. Impacts of nitrogen application rates and tillage modes on yield, nitrogen use efficiency of spring maize and economic benefit. Soil Fertil. Sci. China 2011, 2, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Li, K.K.; Shi, W.J.; Wang, X.L.; Wang, E.T.; Liu, J.F.; Sui, X.H.; Mi, G.H.; Tian, C.F.; Chen, W.X. Negative impacts of excessive nitrogen fertilization on the abundance and diversity of diazotrophs in black soil under maize monocropping. Geoderma 2021, 393, 114999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.B.; Hu, F.L.; Zhao, C.; Feng, F.X.; Yu, A.Z.; Liu, C.; Chai, Q. Response of dry matter accumulation and yield components of maize under n-fertilizer postponing application in oasis irrigation areas. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2017, 50, 2916–2927. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.L.; Li, C.H.; Tan, J.F.; Zhang, X.; Liu, T.X. Effect of postponing n application on yield, nitrogen absorption and utilization in super-high-yield summer maize. Acta Agron. Sin. 2011, 37, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.Z.; Jin, C.W.; Yan, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, J. Effect of application period and ratio of nitrogen fertilizer on photosynthetic and yield of spring maize. Soil Fertil. Sci. China 2017, 5, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.; Chen, X.Y.; Ren, H.; Zhang, J.W.; Zhao, B.; Ren, B.Z.; Liu, P. Deep nitrogen fertilizer placement improves the yield of summer maize (Zea mays L.) by enhancing its photosynthetic performance after silking. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L. Effects of Mulching and Nitrogen Application on Transportation and Utilization of Water and Nitrogen and Productivity in Dryland Spring Maize; Northwest A&F University: Xianyang, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X.P.; Huang, J.K.; Xiang, C.; Powlson, D. Reducing excessive nitrogen use in Chinese wheat production through knowledge training: What are the implications for the public extension system? Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2015, 39, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.J.; Zhang, Y.; Han, W.X.; Tang, A.H.; Shen, J.L.; Cui, Z.L.; Vitousek, P.; Erisman, J.W.; Goulding, K.; Christie, P.; et al. Enhanced nitrogen deposition over China. Nature 2013, 494, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, W.; Hu, C.H.; Oenema, O. Soil mulching significantly enhances yields and water and nitrogen use efficiencies of maize and wheat: A meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.Q.; Lu, D.J.; Chen, X.Q.; Wang, H.Y.; Zu, C.L.; Zhou, J.M. How can urea-N one-time management achieve high yield and high NUE for rainfed and irrigated maize? Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2022, 1222, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Zhang, Y.M.; Zhang, G.Q.; Xu, W.Q.; Xie, R.Z.; Ming, B.; Xue, J.; Li, S.K. Nitrogen application and dense planting to obtain high yields from maize. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.Q.; Liu, C.W.; Xiao, C.H.; Xie, R.Z.; Ming, B.; Hou, P.; Liu, G.Z.; Xu, W.J.; Shen, D.P.; Wang, K.R.; et al. Optimizing water use efficiency and economic return of super high yield spring maize under drip irrigation and plastic mulching in arid areas of China. Field Crop Res. 2017, 211, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shandong Agricultural University. Crop Cultivation; Beijing Agricultural Press: Beijing, China, 1989; pp. 98–206. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, M.B.; Mertens, D.R. Technical Note: Effect of Sample Processing Procedures on Measurement of Starch in Corn Silage and Corn Grain. J. Dairy Sci. 2008, 91, 4830–4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bremner, J.M. Determination of nitrogen in soil by the Kjeldahl method. J. Agric. Sci. 1960, 55, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Z.; Sun, Z.H. Optimized single irrigation can achieve high corn yield and water use efficiency in the corn belt of Northeast China. Eur. J. Agron. 2016, 75, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bänziger, M.; Edmeades, G.O.; Lafitte, H.R. Physiological mechanisms contributing to the increased N stress tolerance of tropical maize selected for drought tolerance. Field Crop Res. 2002, 75, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, S.; Kmail, Z.; Galusha, T.; Jukic, Z. Path analysis of drought tolerant maize hybrid yield and yield components across planting dates. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2019, 20, 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.R.; Yang, Y.; Gong, X.J.; Jiang, Y.B.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, Z.L.; Hao, Y.B.; Liang, L.; Song, Z.W.; Zhang, W.J. Response of grain yield to plant density and nitrogen rate in spring maize hybrids released from 1970 to 2010 in Northeast China. Crop J. 2016, 4, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Zhang, L.; Liang, X.G.; Zhao, X.; Lin, S.; Qu, L.; Liu, Y.P.; Gao, Z.; Ruan, Y.; Zhou, S.L. Delayed pollination and low availability of assimilates are major factors causing maize kernel abortion. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 1599–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, S.M.; Messina, C.D.; Vyn, T.J. The role of the exponential and linear phases of maize (Zea mays L.) ear growth for determination of kernel number and kernel weight. Eur. J. Agron. 2019, 111, 125939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, Q.F.; Ma, T.; Wei, X.X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.H.; Li, Y.; Tang, A.; Gao, J.R.; Zhang, J.; Wei, Y.N.; et al. Improvement of maize post-silking agronomic traits contributes to high grain yield under N-efficient cultivars. Field Crop Res. 2024, 313, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallais, A.; Coque, M.; Gouis, J.; Prioul, J.; Hirel, B.; Quilleré, I. Estimating the proportion of nitrogen remobilization and of post-silking nitrogen uptake allocated to maize kernels by nitrogen-15 labeling. Crop Sci. 2007, 47, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, N.; Fritschi, F.B.; Li, C.J. Temporal dynamics of post-silking nitrogen fluxes and their effects on grain yield in maize under low to high nitrogen inputs. J. Integr. Agric. 2019, 18, 1882–1892. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W.K.; Liu, Z.G.; Zhang, M.; Shi, Y.F.; Zhu, Q.; Sun, Y.B.; Zhou, H.Y.; Li, C.L.; Yang, Y.C.; Geng, J.B. Improving crop yields, nitrogen use efficiencies, and profits by using mixtures of coated controlled-released and uncoated urea in a wheat-maize system. Field Crop Res. 2017, 205, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.C.; Pei, X.X.; He, P.; Zhang, X.Z.; Li, K.J.; Zhou, W.; Liang, G.Q.; Jin, J.Y. Effects of reducing and postponing nitrogen application on soil N supply, plant N uptake and utilization of summer maize. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2010, 16, 492–497. [Google Scholar]

- Díez, J.; Caballero, R.; Bustos, A.; Román, R.; Cartagena, M.; Vallejo, A. Control of nitrate pollution by application of controlled release fertilizer (CRF), compost and an optimized irrigation system. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 1995, 43, 191–195. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Y.S.; Liang, X.Q.; Chen, Y.X.; Liu, J.; Gu, J.T.; Guo, R.; Li, L. Alternate wetting and drying irrigation and controlled-release nitrogen fertilizer in late-season rice. Effects on dry matter accumulation yield, water and nitrogen use. Field Crop Res. 2013, 144, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, H.H.; Sun, J.Q.; Li, J.C.; Song, Y.H. Seedling characteristics and grain yield of maize grown under straw retention affected by sowing irrigation and splitting nitrogen use. Field Crop Res. 2018, 225, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosgey, J.R.; Moot, D.J.; Fletcher, A.L.; McKenzie, B.A. Dry matter accumulation and post-silking N economy of ‘stay green’ maize (Zea mays L.) hybrids. Eur. J. Agron. 2013, 51, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.B.; Cui, H.Y.; Li, B.; Yang, J.S.; Dong, S.T.; Zhao, B.; Liu, P.; Zhang, J.W. Effects of integrated agronomic practices on nitrogen efficiency and soil nitrate nitrogen of summer maize. Acta Agron. Sin. 2013, 39, 2009–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nitrogen Application (kg ha−1) | Treatment | Timing and Ratios of Nitrogen Application (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal Fertilizer | V9 | V12 | V15 | R1 − 4d | R1 + 6d | R1 + 13d | R3 | R3 + 9d | ||

| 0 | N0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 360 | Fbase | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F0% | 0 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| F20% | 0 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| F40% | 0 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

| F60% | 0 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | |

| F80% | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | |

| F100% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | |

| Year | Density (× 104 Plant ha−1) | Nitrogen Application (kg ha−1) | Treatment | Yield (kg·ha−1) | Ears Number (Ears·ha−1) | Kernel Number per Ear | 1000-Kernel Weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 7.5 | 0 | N0 | 14.49 f | 7.03 a | 442.67 f | 305.94 f |

| 360 | Fbase | 15.96 e | 7.21 a | 561.33 d | 334.68 e | ||

| F0% | 17.7 bc | 7.21 a | 59.00 c | 355.54 c | |||

| F20% | 17.44 cd | 7.27 a | 592.67 bc | 357.83 bc | |||

| F40% | 17.89 b | 7.03 a | 605.33 ab | 360.00 ab | |||

| F60% | 18.29 a | 7.03 a | 610.00 a | 363.74 a | |||

| F80% | 17.12 d | 7.33 a | 536.67 e | 354.15 c | |||

| F100% | 16.25 e | 7.03 a | 536.00 e | 341.25 d | |||

| 12.0 | 0 | N0 | 12.46 g | 10.55 a | 386.00 e | 296.03 f | |

| 360 | Fbase | 19.31 e | 10.79 a | 454.00 c | 327.71 e | ||

| F0% | 21.36 b | 10.91 a | 496.67 b | 341.35 bc | |||

| F20% | 21.57 ab | 10.79 a | 504.67 a | 343.47 b | |||

| F40% | 21.83 a | 10.97 a | 509.33 a | 352.36 a | |||

| F60% | 21.01 c | 10.97 a | 492.67 b | 338.46 c | |||

| F80% | 20.30 d | 10.91 a | 451.33 c | 332.47 d | |||

| F100% | 18.98 f | 10.79 a | 440.67 d | 324.93 e | |||

| 2024 | 7.5 | 0 | N0 | 14.33 g | 7.33 a | 382.67 e | 352.04 f |

| 360 | Fbase | 16.94 f | 7.33 a | 626.00 cd | 390.01 e | ||

| F0% | 19.07 c | 7.33 a | 640.00 bc | 411.29 c | |||

| F20% | 19.28 bc | 7.39 a | 641.33 ab | 404.87 d | |||

| F40% | 19.47 b | 7.45 a | 647.33 ab | 419.77 ab | |||

| F60% | 20.00 a | 7.33 a | 655.33 a | 423.47 a | |||

| F80% | 18.38 d | 7.39 a | 616.00 d | 414.74 bc | |||

| F100% | 17.41 e | 7.27 a | 617.33 d | 399.85 d | |||

| 12.0 | 0 | N0 | 14.78 f | 10.85 a | 331.33 d | 343.50 f | |

| 360 | Fbase | 18.53 e | 10.79 a | 495.33 c | 353.34 e | ||

| F0% | 20.91 b | 10.85 a | 522.00 b | 363.76 c | |||

| F20% | 20.98 ab | 10.91 a | 536.67 ab | 367.35 ab | |||

| F40% | 21.45 a | 10.91 a | 544.67 a | 368.50 a | |||

| F60% | 21.32 ab | 10.97 a | 524.00 b | 366.09 b | |||

| F80% | 20.32 c | 10.85 a | 486.00 c | 354.76 de | |||

| F100% | 19.57 d | 10.85 a | 486.00 c | 355.48 d | |||

| Source of variation | |||||||

| Year (Y) | ** | * | ** | ** | |||

| Density (D) | ** | ** | ** | ** | |||

| Treatment (T) | ** | ns | ** | ** | |||

| Y × D | ** | ns | ** | ** | |||

| Y × T | ** | ns | ** | ** | |||

| D × T | ** | ns | ** | ** | |||

| Y × D × T | ** | ns | ** | ** | |||

| Density (×104 Plant ha−1) | Treatment | Model | R2 | Calculated Values | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t1 (d) | t2 (d) | T (d) | Vmax | Wmax | ||||

| 7.5 | Fbase | Y = 260.01/(1 + 243.44 × 10−0.08x) | 0.9998 ** | 51.04 | 83.22 | 32.18 | 5.32 | 260.01 |

| F0% | Y = 288.82/(1 + 199.96 × 10−0.07x) | 0.9986 * | 54.15 | 89.97 | 35.82 | 5.31 | 288.82 | |

| F20% | Y = 302.91/(1 + 74.97 × 10−0.06x) | 0.9988 ** | 52.26 | 98.14 | 45.88 | 4.35 | 302.91 | |

| F40% | Y = 369.89/(1 + 36.04 × 10−0.04x) | 0.9987 ** | 54.98 | 118.84 | 63.86 | 3.81 | 369.89 | |

| F60% | Y = 386.06/(1 + 46.94 × 10−0.04x) | 0.9994 ** | 59.81 | 122.02 | 62.21 | 4.09 | 386.06 | |

| F80% | Y = 324.13/(1 + 44.44 × 10−0.04x) | 0.9995 ** | 55.73 | 114.98 | 59.25 | 3.60 | 324.13 | |

| F100% | Y = 282.06/(1 + 34.00 × 10−0.04x) | 0.9981 * | 52.31 | 114.66 | 62.35 | 2.98 | 282.06 | |

| 12.0 | Fbase | Y = 253.56/(1 + 196.72 × 10−0.09x) | 0.9998 ** | 45.31 | 75.41 | 30.10 | 5.55 | 253.56 |

| F0% | Y = 339.04/(1 + 33.05 × 10−0.05x) | 0.9979 ** | 45.46 | 100.35 | 54.89 | 4.07 | 339.04 | |

| F20% | Y = 406.00/(1 + 31.06 × 10−0.04x) | 0.9985 ** | 51.10 | 114.61 | 63.51 | 4.21 | 406.00 | |

| F40% | Y = 414.88/(1 + 26.53 × 10−0.04x) | 0.9983 ** | 51.71 | 121.14 | 69.43 | 3.93 | 414.88 | |

| F60% | Y = 403.77/(1 + 24.53 × 10−0.04x) | 0.9978 ** | 52.41 | 125.73 | 73.32 | 3.63 | 403.77 | |

| F80% | Y = 342.81/(1 + 29.45 × 10−0.04x) | 0.9977 * | 50.35 | 114.54 | 64.19 | 3.52 | 342.81 | |

| F100% | Y = 295.75/(1 + 19.13 × 10−0.04x) | 0.9955 * | 43.61 | 113.88 | 70.28 | 2.77 | 295.75 | |

| Density (×104 Plant ha−1) | Treatment | PSNT (kg ha−1) | PSNTR (%) | CR-PSNT (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf | Stem | Total | Leaf | Stem | Total | Leaf | Stem | Total | ||

| 7.5 | Fbase | 69.34 a | 60.95 a | 130.29 a | 64.27 a | 70.27 a | 66.96 a | 39.32 a | 34.02 a | 73.35 a |

| F0% | 62.77 ab | 61.59 a | 124.35 ab | 60.33 a | 66.21 b | 63.15 b | 28.99 b | 28.24 b | 57.22 b | |

| F20% | 58.78 b | 57.13 b | 115.91 b | 59.65 a | 66.36 b | 62.67 b | 25.99 b | 25.20 c | 51.19 c | |

| F40% | 38.68 c | 43.51 c | 82.19 c | 39.93 c | 52.56 c | 45.77 c | 15.78 cd | 17.74 d | 33.52 d | |

| F60% | 35.00 c | 36.86 d | 71.86 de | 37.49 c | 47.98 d | 42.19 d | 13.75 d | 14.45 e | 28.21 e | |

| F80% | 41.35 c | 38.98 d | 80.32 cd | 44.67 b | 53.95 c | 48.93 c | 18.60 c | 17.69 d | 36.29 d | |

| F100% | 34.22 c | 29.90 e | 64.12 e | 46.01 b | 49.63 d | 47.73 c | 18.20 c | 15.73 e | 33.93 d | |

| 12 | Fbase | 61.96 a | 64.03 a | 137.65 a | 60.93 a | 62.29 a | 68.74 a | 35.78 a | 35.80 a | 76.75 a |

| F0% | 54.71 b | 59.24 b | 124.73 b | 51.57 b | 58.04 b | 61.27 b | 22.65 b | 23.84 b | 52.34 b | |

| F20% | 45.31 c | 50.05 c | 116.77 c | 42.18 cd | 51.56 c | 59.32 c | 16.16 cd | 17.67 c | 44.22 c | |

| F40% | 41.50 cd | 37.95 d | 92.90 d | 40.44 d | 40.38 e | 48.91 e | 15.41 d | 13.67 d | 34.39 e | |

| F60% | 43.08 cd | 32.23 e | 78.69 e | 43.99 c | 39.86 e | 44.32 f | 16.59 cd | 12.36 d | 30.00 f | |

| F80% | 40.73 d | 27.73 f | 78.87 e | 42.83 cd | 39.31 e | 48.35 e | 18.10 c | 12.41 d | 35.57 e | |

| F100% | 44.26 cd | 27.28 f | 79.90 e | 48.93 b | 44.86 d | 53.11 d | 22.50 b | 13.89 d | 41.17 d | |

| Density (×104 Plant ha−1) | Treatment | NUE (%) | NPE (kg kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7.5 | Fbase | 31.01 g | 17.84 e |

| F0% | 44.05 e | 24.88 a | |

| F20% | 46.76 d | 23.13 b | |

| F40% | 60.04 b | 19.56 cd | |

| F60% | 61.08 a | 21.88 c | |

| F80% | 48.41 c | 19.09 de | |

| F100% | 36.04 f | 18.36 e | |

| 12 | Fbase | 34.46 g | 42.69 a |

| F0% | 57.57 d | 36.48 b | |

| F20% | 71.09 b | 30.55 d | |

| F40% | 72.81 a | 30.33 d | |

| F60% | 64.73 c | 32.54 c | |

| F80% | 53.79 e | 33.59 c | |

| F100% | 41.89 f | 36.69 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhai, J.; Cao, Y.; Xu, W.; Ming, B.; Xie, R.; Wang, K.; Li, S.; Xue, J.; et al. Post-Silking Nitrogen Topdressing Optimizes Nitrogen Accumulation and Enhances Yield in Densely Planted Maize. Agronomy 2026, 16, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010026

Zhang Y, Zhang G, Zhai J, Cao Y, Xu W, Ming B, Xie R, Wang K, Li S, Xue J, et al. Post-Silking Nitrogen Topdressing Optimizes Nitrogen Accumulation and Enhances Yield in Densely Planted Maize. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yuanmeng, Guoqiang Zhang, Juan Zhai, Yuehong Cao, Wenqian Xu, Bo Ming, Ruizhi Xie, Keru Wang, Shaokun Li, Jun Xue, and et al. 2026. "Post-Silking Nitrogen Topdressing Optimizes Nitrogen Accumulation and Enhances Yield in Densely Planted Maize" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010026

APA StyleZhang, Y., Zhang, G., Zhai, J., Cao, Y., Xu, W., Ming, B., Xie, R., Wang, K., Li, S., Xue, J., & Wang, Z. (2026). Post-Silking Nitrogen Topdressing Optimizes Nitrogen Accumulation and Enhances Yield in Densely Planted Maize. Agronomy, 16(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010026