Exogenous Paclobutrazol Promotes Tiller Initiation in Rice Seedlings by Enhancing Sucrose Translocation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Planting Method

2.2. Analysis of Seedling Quality-Related Parameters

2.3. Determination of Hormone Contents

2.4. Determination of Chlorophyll Contents

2.5. Determination of Non-Structural Carbohydrate (NSC), Sucrose, Fructose, Glucose, and Starch Contents

2.6. RNA Extraction from Leaves and the Stem Base of Seedlings and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR) Analysis

2.7. Determination of Soluble Acid Invertase (S-AI), Sucrose Phosphate Synthase (SPS), 6-Phosphofructokinase (PFK), Pyruvate Kinase (PK), Pyruvate Dehydrogenase (PDH), and Cytoplasmic Isocitrate Dehydrogenase (ICDHc) Activities

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. PBZ Application Promotes Low-Position Tiller Initiation in Rice Seedlings

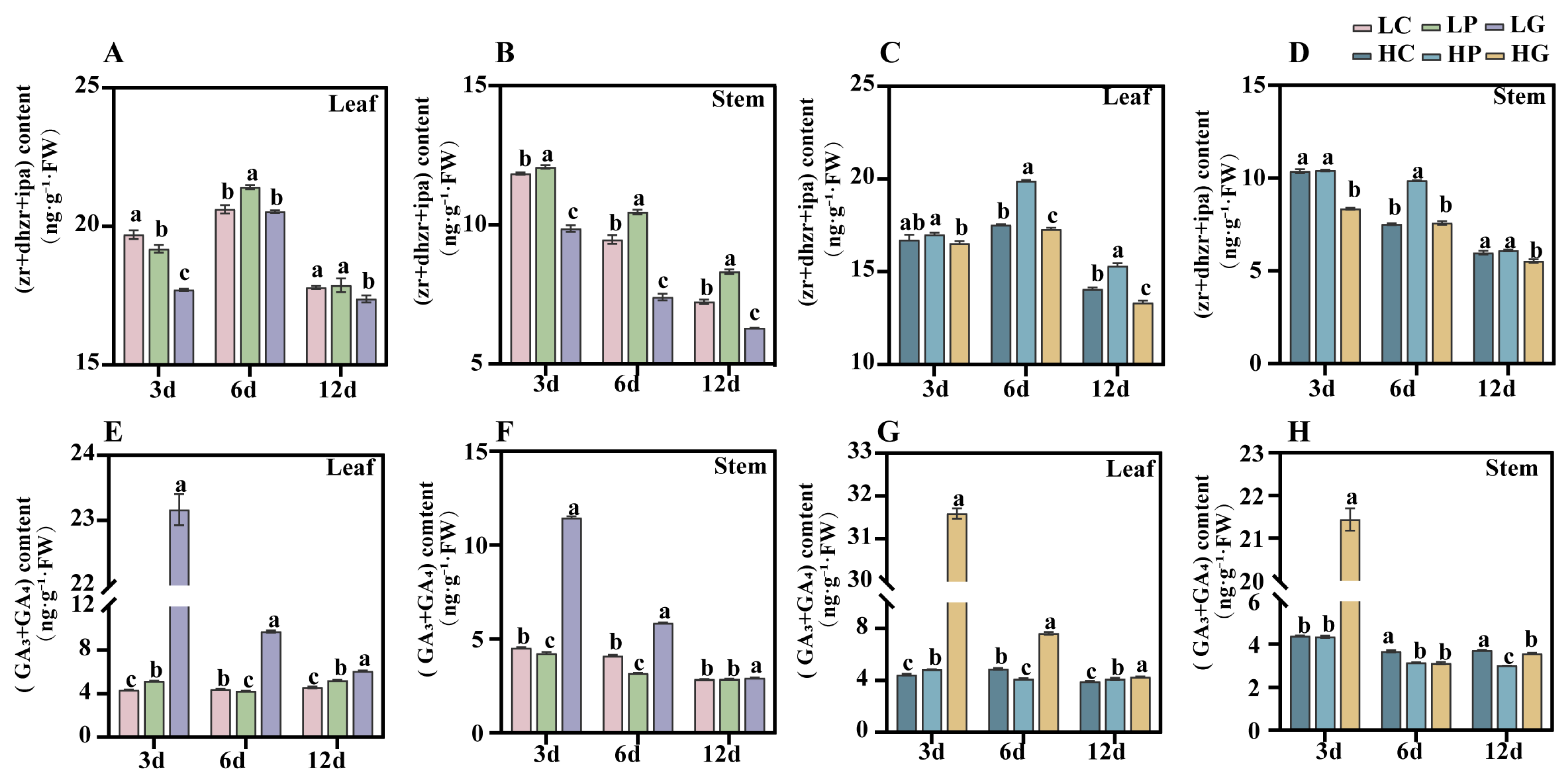

3.2. PBZ Treatment Increases Cytokinin Content

3.3. PBZ Treatment Increases Seedling Chlorophyll Contents

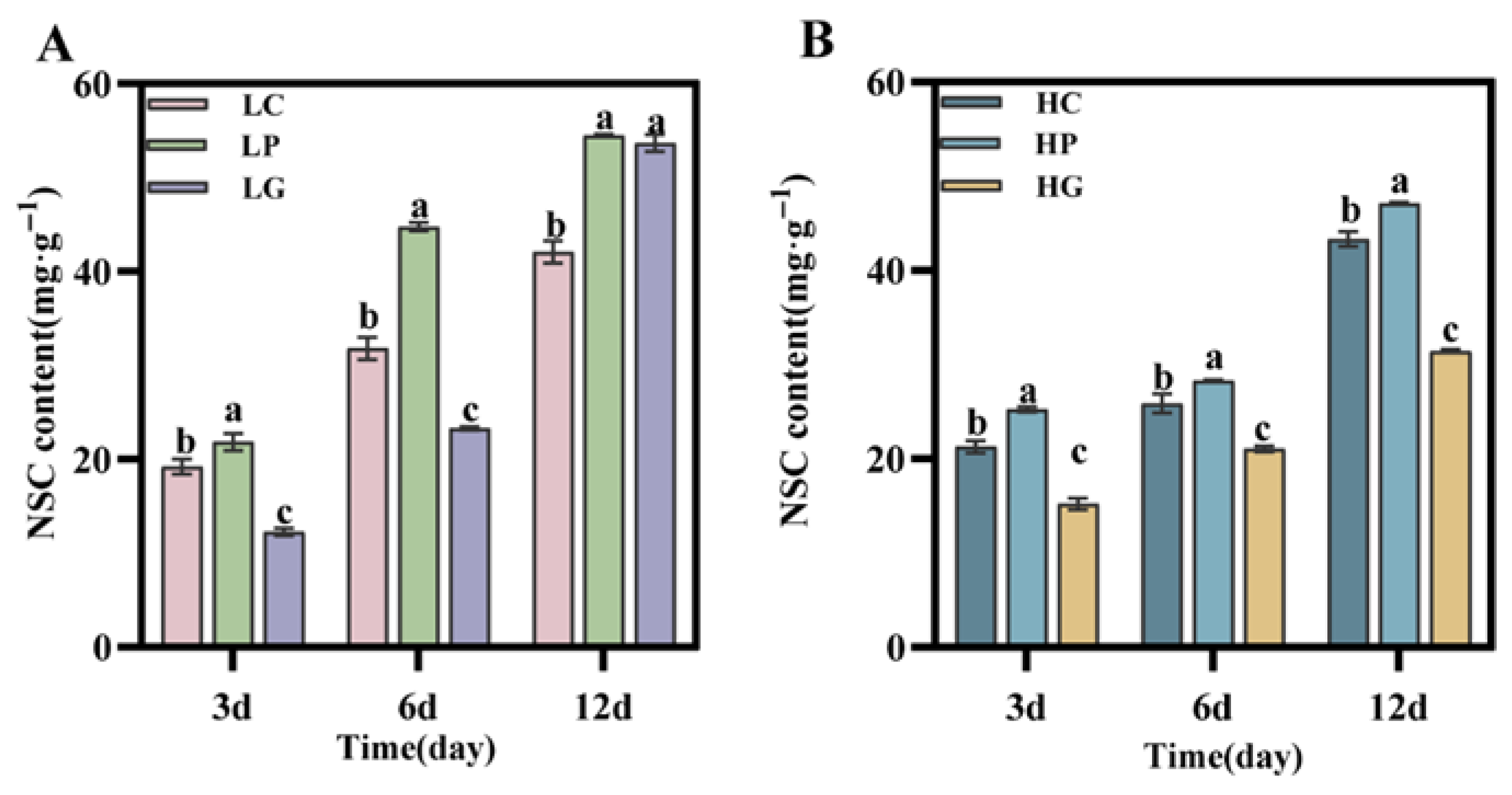

3.4. PBZ Application Enhances Carbohydrate Accumulation in the Stem Base

3.5. PBZ Upregulates Sucrose Transporter Gene Expression

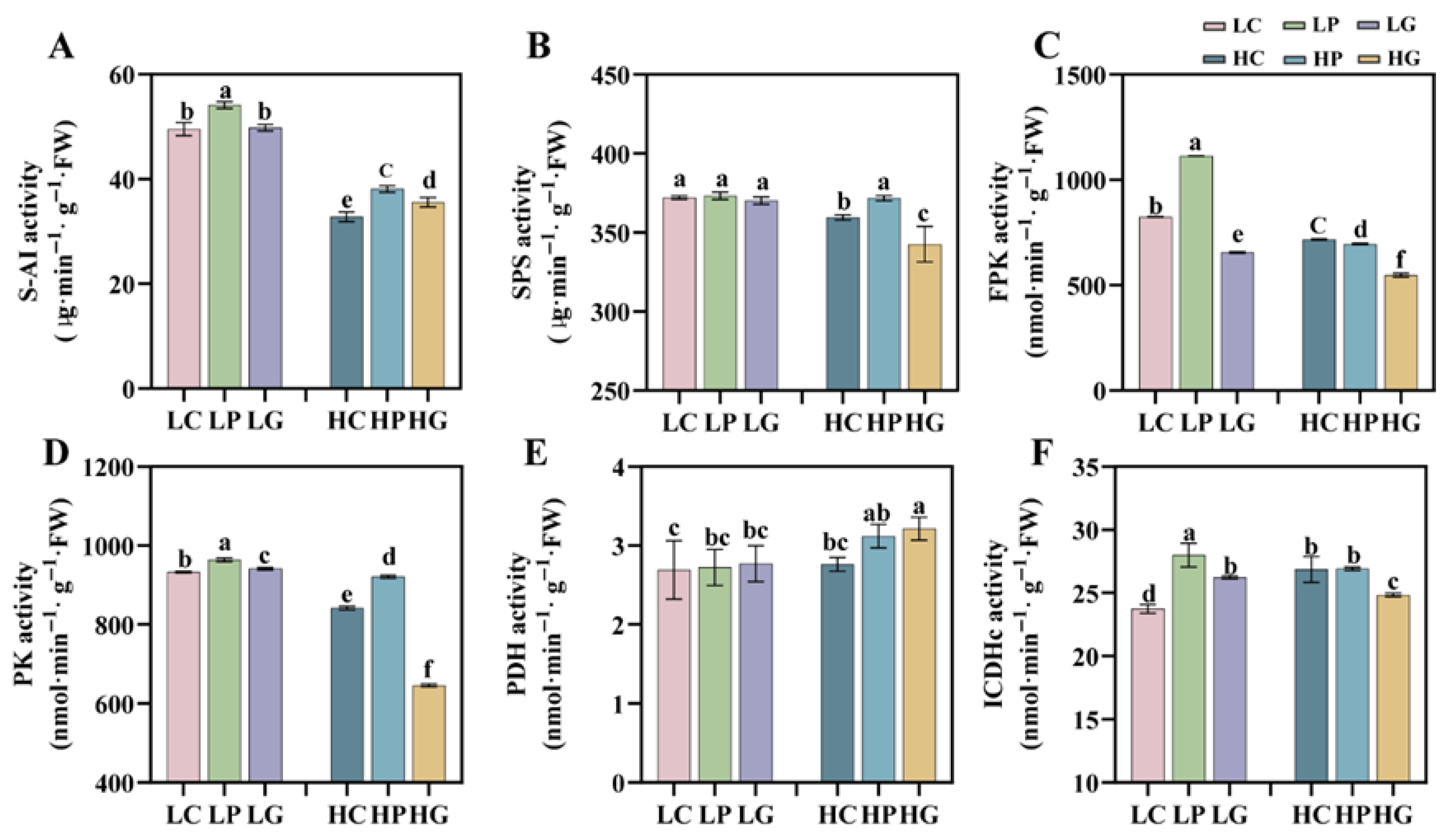

3.6. PBZ Enhances Sucrose-Metabolizing Enzyme Activities

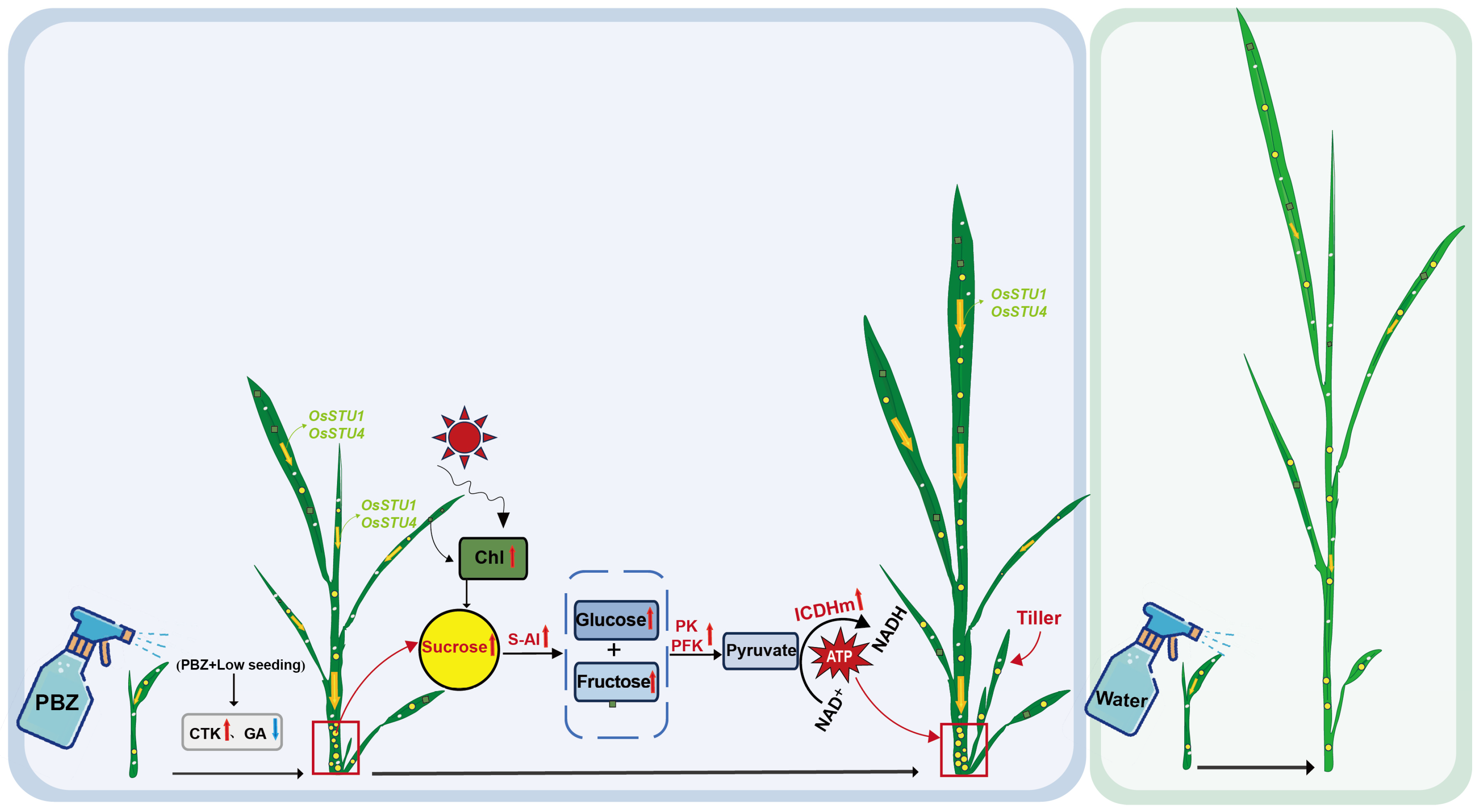

4. Discussion

4.1. PBZ Application Combined with a Low Seeding Rate Promotes Tiller Bud Development in Seedlings

4.2. PBZ Enhances Sucrose Transport and Accumulation in Seedlings

4.3. PBZ Coordinates Hormone Signaling and Enhances Sucrose Metabolism at the Stem Base

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CTK | Cytokinin |

| DHZR | Dihydrozeatin riboside |

| ICDHc | Isocitrate dehydrogenase |

| IPA | Isopentenyl adenine |

| IAA | Indole Acetic Acid |

| NSC | Non-structural carbohydrate |

| PBZ | Paclobutrazol |

| PFK | 6-phosphofructokinase |

| PK | pyruvate kinase |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative real-time PCR |

| SPS | Sucrose phosphate synthase |

| SS-I | Sucrose synthase I |

| SLS | Strigolactones |

| Z | Zeatin |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Cultivar | Spraying Concentration (mg/L) | LEAF AGE | Stem Base Width (mm) | Seedling Height (cm) | Tiller (Number) | Seedling Plumpness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yongyou 12 | 0 | 4.56 ± 0.14 a | 3.38 ± 0.14 c | 18.48 ± 1.13 a | 0.00 ± 0.00 c | 1.97 ± 0.04 c |

| 100 | 4.63 ± 0.04 a | 4.28 ± 0.44 b | 12.65 ± 0.91 b | 0.60 ± 0.20 b | 2.98 ± 0.33 b | |

| 200 | 4.71 ± 0.06 a | 4.92 ± 0.6 ab | 10.58 ± 0.85 c | 0.80 ± 0.20 b | 3.54 ± 0.31 b | |

| 300 | 4.72 ± 0.10 a | 5.53 ± 0.23 a | 10.10 ± 0.36 c | 1.13 ± 0.11 a | 4.11 ± 0.33 a | |

| 400 | 4.56 ± 0.15 a | 5.46 ± 0.73 a | 9.21 ± 0.80 c | 0.73 ± 0.11 b | 4.22 ± 0.40 a |

Appendix A.2

| Gene | Forward Primer (5′–3′) | Reverse Primer (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| OsSUT1 | ATGTGGCTCTGTGGTCCTATTGC | TCAACACACATCCTGTAAGAATA |

| OsSUT4 | TTCTCCCTACTTGGACTGCCACTCT | TCCTGTTGCCAGACCTTGTCCACCT |

| actin | TTATGGTTGGGATGGGACA | AGCACGGCTTGAATAGCG |

Appendix A.3

| Ariety | Treatment | Productive Panicle Number (×105·ha) | The Number of Spikelet per Panicle | Spikelet Fertility Rate (%) | 1000-Grain Weigh (g) | Grain Yield (t·ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yongyou 1540 | Seedlings with tillers | 17.77 ± 0.29 * | 217.04 ± 11.45 | 87.11 ± 1.05 | 23.09 ± 0.26 | 7.75 ± 0.34 * |

| Seedlings without tillers | 16.76 ± 0.16 | 211.38 ± 15.75 | 86.91 ± 0.33 | 22.18 ± 0.81 | 6.81 ± 0.26 |

References

- Karim, M.R.; Alam, M.M.; Ladha, J.K.; Islam, M.S.; Islam, M.R. Effect of different irrigation and tillage methods on yield and resource use efficiency of boro rice (Oryza sativa). Bangladesh J. Agric. Res. 2014, 39, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Zou, Y.B. Integrating mechanization with agronomy and breeding to ensure food security in China. Field Crops Res. 2018, 224, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.H.; Goswami, P.C.; Hossain, M.F.; Mahalder, D.; Rony, M.K.I.; Shirazy, B.J.; Russell, T.D. Mechanised non-puddled transplanting of boro rice following mustard conserves resources and enhances productivity. Field Crops Res. 2018, 225, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H. Research of the Completion of High Yield Population and its Physiological and Ecological Characteristics of Bowl Mechanical-Transplanting Indica Hybrid Rice in Chengdu Plain. Master’s Thesis, Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, R. Characteristics and seedling establishment of rice nursling seedlings. Jarq-Jpn. Agric. Res. Q. 2004, 38, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.S.; Zhang, H.C.; Dai, Q.; Huo, Z.Y.; Xu, K.; Wei, H.Y.; Zhu, C.C.; Sun, Z.; Yang, D.L.; Wang, W.Q.; et al. Seedling quality regulation of rice potted-seedling in mechanical transplanting. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2013, 29, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, W.S.; Zeng, Y.J.; Shi, Q.H.; Pan, X.H.; Huang, S.; Shang, Q.Y.; Tan, X.M.; Li, M.Y.; Hu, S.X. Ttillering and panicle formation characteristics of machine-transplanted early rice and its parameters of basic population formulae. Acta Agron. Sin. 2016, 42, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.H.; Wang, J.Q.; Chen, H.Z.; Zhang, Y.P.; Xiang, J.; Zhang, Y.K.; Wang, Z.G.; Huai, Y.; Chen, J.F.; Wang, Y.L. Effects of Hybrid Rice Seedling Quality in Drill-seeding Nursery on Grain Yield in Mechanical Transplanting. Chin. J. Rice Sci. 2025, 39, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumya, P.R.; Pramod Kumar, P.K.; Madan Pal, M.P. Paclobutrazol: A novel plant growth regulator and multi-stress ameliorant. Indian J. Plant Physiol. 2017, 22, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.Y.; Cui, J.H.; Ran, C.; Zhang, Y.C.; Liang, J.N.; Shao, X.W.; Zhang, Q.; Geng, Y.Q.; Guo, L.Y. Paclobutrazol enhanced stem lodging resistance of direct-seeded rice by affecting basal internode development. Plants 2024, 13, 2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.Y.; Gai, D.S.; Liang, J.N.; Cui, J.H.; Geng, Y.Q.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, L.Y.; Shao, X.W. Paclobutrazol enhances lodging resistance and yield of direct-seeded rice by optimizing plant type and canopy light transmittance. Field Crops Res. 2025, 331, 109882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Smith, S.M.; Li, J. Genetic regulation of shoot architecture. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2018, 69, 437–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, R.; Zhu, M.D.; Yu, J.M.; Kou, L.Q.; Ahmad, S.; Wei, X.J.; Jiao, G.A.; Hu, S.K.; Sheng, Z.H.; Zhao, F.L.; et al. Photosynthesis regulates tillering bud elongation and nitrogen--use efficiency via sugar-induced NGR5 in rice. New Phytol. 2024, 243, 1440–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H.; Imamura, T.; Konno, N.; Takeda, T.; Fujita, K.; Konishi, T.; Nishihara, M.; Uchimiya, H. The gentio-oligosaccharide gentiobiose functions in the modulation of bud dormancy in the herbaceous perennial gentiana. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 3949–3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbier, F.; Péron, T.; Lecerf, M.; Perez-Garcia, M.-D.; Barrière, Q.; Rolčík, J.; Boutet-Mercey, S.; Citerne, S.; Lemoine, R.; Porcheron, B.; et al. Sucrose is an early modulator of the key hormonal mechanisms controlling bud outgrowth in Rosa hybrida. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 2569–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, F.F.; Lunn, J.E.; Beveridge, C.A. Ready, steady, go! A sugar hit starts the race to shoot branching. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2015, 25, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, D.; Waldie, T.; Miyawaki, K.; To, J.P.C.; Melnyk, C.W.; Kieber, J.J.; Kakimoto, T.; Leyser, O. Cytokinin is required for escape but not release from auxin mediated apical dominance. Plant J. 2015, 82, 874–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.B.; Barbier, F.F.; Zhao, J.; Zafar, S.A.; Uzair, M.; Sun, Y.; Fang, J.; Perez--Garcia, M.D.; Bertheloot, J.; Sakr, S.; et al. Sucrose promotes D53 accumulation and tillering in rice. New Phytol. 2021, 234, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L.; Cui, Y.T.; Hu, G.H.; Wang, X.D.; Chen, H.Z.; Shi, Q.H.; Xiang, J.; Zhang, Y.K.; Zhu, D.F.; Zhang, Y.P. Reduced bioactive gibberellin content in rice seeds under low temperature leads to decreased sugar consumption and low seed germination rates. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 133, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnon, D.I. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. polyphenoloxidase in beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949, 24, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wu, X.; Chen, Y.L.; Ji, G.M.; Ma, X.L.; Zhang, Y.P.; Xiang, J.; Wang, Y.L.; Wang, Z.G.; Li, L.T.; et al. Comparative transcriptome combined with morphophysiological analyses revealed carotenoid biosynthesis for differential chilling tolerance in two contrasting rice (Oryza sativa L.) genotypes. Rice 2023, 16, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocready, R.M.; Guggolz, J.; Silviera, V.; Owens, H.S. Determination of starch and amylose in vegetables. Application to peas. Anal. Chem. 1950, 22, 1156–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Q.; Li, H.; Lan, T.M.; Tang, C.H.; Zhang, P.; Chen, Y.L.; Chen, H.Z.; Xiang, J.; Zhang, Y.K.; Wang, Z.G.; et al. Positional differences of rice spikelet formation under high temperature are associated with sucrose utilization discrepancy. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2025, 232, 106114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, N.; Hirose, T.; Scofield, G.N.; Whitfeld, P.R.; Furbank, R.T. The sucrose transporter gene family in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003, 44, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bari, R.; Jones, J.D.G. Role of plant hormones in plant defence responses. Plant Mol. Biol. 2008, 69, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kariali, E.; Mohapatra, P.K. Hormonal regulation of tiller dynamics in differentially-tillering rice cultivars. Plant Growth Regul. 2007, 53, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.H.; van de Peppel, A.; Li, X.Y.; Welander, M. Changes of leaf water potential and endogenous cytokinins in young apple trees treated with or without paclobutrazol under drought conditions. Sci. Hortic. 2004, 99, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.W.; Gao, P.L.; Wang, H.Y.; Chen, Y.L.; Wei, H.H.; Dai, Q.G. Effects of mixed planting on machine transplanting adaptability and grain yield of hybrid rice. Agriculture 2023, 13, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Liu, M.Z.; Wang, K.T.; Ling, Y.F.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, H.C.; Zhang, H.P. Optimal seeding rate enhances seedling quality, mechanical transplanting quality, and yield in hybrid rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1427972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, W.H.; Jeong, J.H.; Lee, H.S.; Yang, S.Y.; Lee, C.G. Seeding rate and days for low-density transplant cultivation. Korean J. Crop Sci. 2021, 66, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L.; Zhu, D.F.; Chen, R.X.; Fang, W.Y.; Wang, J.Q.; Xiang, J.; Chen, H.Z.; Zhang, Y.P.; Chen, J.H. Beneficial effects of precision drill sowing with low seeding rates in machine transplanting for hybrid rice to improve population uniformity and yield. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2022, 55, 666–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.Q.; Li, J.; Zhong, P.; Dong, Y.B.; Sun, C.M.; Zhuang, C.; Chen, C.; Zhang, A.K. Effects of tray seedling and sowing rate on quality of mechanical transplanting rice seedlings. J. Ofsouthern Agric. 2019, 50, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh Mohammadi, M.H.; Etemadi, N.; Marab, M.; Aalifar, M.; Arab, M.; Pessarakli, M. Molecular and physiological responses of Iranian Perennial ryegrass as affected by Trinexapac ethyl, Paclobutrazol and Abscisic acid under drought stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 111, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Ma, X.P.; Lv, T.B.; Bai, M.; Wang, Z.L.; Niu, J.R. Effects of water stress on fluorescence parameters and photosynthetic characteristics of drip irrigation in rice. Water 2020, 12, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, P.P.; Duan, M.Y.; Liu, Y.H.; Mo, Z.W.; Lai, R.F.; Tang, X.R. Enhancement of yield, grain quality characters, 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline content, and photosynthesis of fragrant rice cultivars by foliar application of paclobutrazol. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 42, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Tang, Y.H.; Wei, M.R.; Zhao, D.Q. Effect of paclobutrazol application on plant photosynthetic performance and leaf greenness of herbaceous peony. Horticulturae 2018, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauzin, A.S.; Giardina, T. Sucrose and invertases, a part of the plant defense response to the biotic stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Y.L. Sucrose metabolism: Gateway to diverse carbon use and sugar signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2014, 65, 33–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.J.; Li, H.Y.; Zhu, Q.D.; Liu, D.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.F.; Luo, J.S.; Gong, P.; Ismail, A.M.; Zhang, Z.H. Knockout of the sugar transporter OsSTP15 enhances grain yield by improving tiller number due to increased sugar content in the shoot base of rice (Oryza sativa L.). New Phytol. 2023, 241, 1250–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assuero, S.G.; Lorenzo, M.; Ramírez, N.M.P.; Velázquez, L.M.; Tognetti, J.A. Tillering promotion by paclobutrazol in wheat and its relationship with plant carbohydrate status. N. Z. J. Agric. Res. 2012, 55, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, C.M.; Feil, R.; Ishihara, H.; Watanabe, M.; Kölling, K.; Krause, U.; Höhne, M.; Encke, B.; Plaxton, W.C.; Zeeman, S.C.; et al. Trehalose 6-phosphate coordinates organic and amino acid metabolism with carbon availability. Plant J. 2016, 85, 410–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dun, E.A.; de Saint Germain, A.; Rameau, C.; Beveridge, C.A. Antagonistic action of strigolactone and cytokinin in bud outgrowth control. Plant Physiol. 2012, 158, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kieber, J.J.; Schaller, G.E. Cytokinin signaling in plant development. Development 2018, 145, dev149344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.Q.; Dai, Y.D.; Peng, Z.W.; Cui, Z.B.; Zhang, X.F.; Li, Y.Y.; Tian, W.J.; He, G.h.; Li, Y.; Sang, X.C. The auxin transporter OsAUX1 regulates tillering in rice (Oryza sativa). J. Integr. Agric. 2024, 23, 1454–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, F.F.; Dun, E.A.; Kerr, S.C.; Chabikwa, T.G.; Beveridge, C.A. An update on the signals controlling shoot branching. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 220–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setia, R.C.; Bhathal, G.; Setia, N. Influence of paclobutrazol on growth and yield of brassica-carinata a.br. Plant Growth Regul. 1995, 16, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinniah, U.R.; Wahyuni, S.; Syahputra, B.S.A.; Gantait, S. A potential retardant for lodging resistance in direct seeded rice (Oryza sativa L.). Can. J. Plant Sci. 2012, 92, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.G.; Yu, H.; Duan, J.B.; Yuan, K.; Yu, C.J.; Meng, X.B.; Kou, L.Q.; Chen, M.J.; Jing, Y.H.; Liu, G.F.; et al. SLR1 inhibits MOC1 degradation to coordinate tiller number and plant height in rice. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrein, B.; Formosa-Jordan, P.; Malivert, A.; Schuster, C.; Melnyk, C.W.; Yang, W.; Turnbull, C.; Meyerowitz, E.M.; Locke, J.C.W.; Jönsson, H. Nitrate modulates stem cell dynamics in Arabidopsis shoot meristems through cytokinins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 1382–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, I.; Scheirlinck, M.-T.; Otto, E.; Bartrina, I.; Schmidt, R.-C.; Schmülling, T.; Dodd, I. Cytokinin regulates the activity of the inflorescence meristem and components of seed yield in oilseed rape. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 7146–7159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Tao, J.Y.; Chang, Y.Y.; Wang, D.J.; Wu, Y.Y.; Gu, C.X.; Tao, W.Q.; Wang, H.M.; Xie, X.N.; Zhang, Y.L. Cytokinin catabolism and transport are involved in strigolactone-modulated rice tiller bud elongation fueled by phosphate and nitrogen supply. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 215, 108982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, T.Y.; Wang, T.H.; Sun, Y.L.; Kumar, A.; Mkumbwa, H.; Fang, J.J.; Zhao, J.F.; Yuan, S.J.; Li, Z.C.; Li, X.Y. The chloroplast pentatricopeptide repeat protein RCN22 regulates tiller number in rice by affecting sugar levels via the TB1–RCN22–RbcL module. Plant Commun. 2024, 5, 101073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Test Treatment Number | Treatment |

|---|---|

| LC | Low sowing rate, control |

| LP | Low seeding rate, exogenous spraying PBZ |

| LG | Low seeding rate, exogenous spraying GA3 |

| HC | High sowing rate, control |

| HP | High seeding rate, exogenous spraying PBZ |

| HG | High seeding rate, exogenous spraying GA3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, H.; Lan, T.; Wang, J.; Liang, H.; Wang, Z.; Xiang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Exogenous Paclobutrazol Promotes Tiller Initiation in Rice Seedlings by Enhancing Sucrose Translocation. Agronomy 2026, 16, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010025

Li H, Lan T, Wang J, Liang H, Wang Z, Xiang J, Zhang Y, Chen H, Xu Y, Zhang Y, et al. Exogenous Paclobutrazol Promotes Tiller Initiation in Rice Seedlings by Enhancing Sucrose Translocation. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Hui, Tianming Lan, Jingqing Wang, Huizhou Liang, Zhigang Wang, Jing Xiang, Yikai Zhang, Huizhe Chen, Yiwen Xu, Yuping Zhang, and et al. 2026. "Exogenous Paclobutrazol Promotes Tiller Initiation in Rice Seedlings by Enhancing Sucrose Translocation" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010025

APA StyleLi, H., Lan, T., Wang, J., Liang, H., Wang, Z., Xiang, J., Zhang, Y., Chen, H., Xu, Y., Zhang, Y., & Wang, Y. (2026). Exogenous Paclobutrazol Promotes Tiller Initiation in Rice Seedlings by Enhancing Sucrose Translocation. Agronomy, 16(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010025