Microbial Metagenomics Evidence Reveals Forest Soil Amendment Contributes to Increased Sugarcane Yields in Long-Term Cropping Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil Sampling and Experimental Design

2.2. DNA Extraction and Metagenomic Sequencing

2.3. Metagenomic Data Processing and Annotation

2.4. Statistical and Bioinformatic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Forest Soil Amendment on Microbial Community

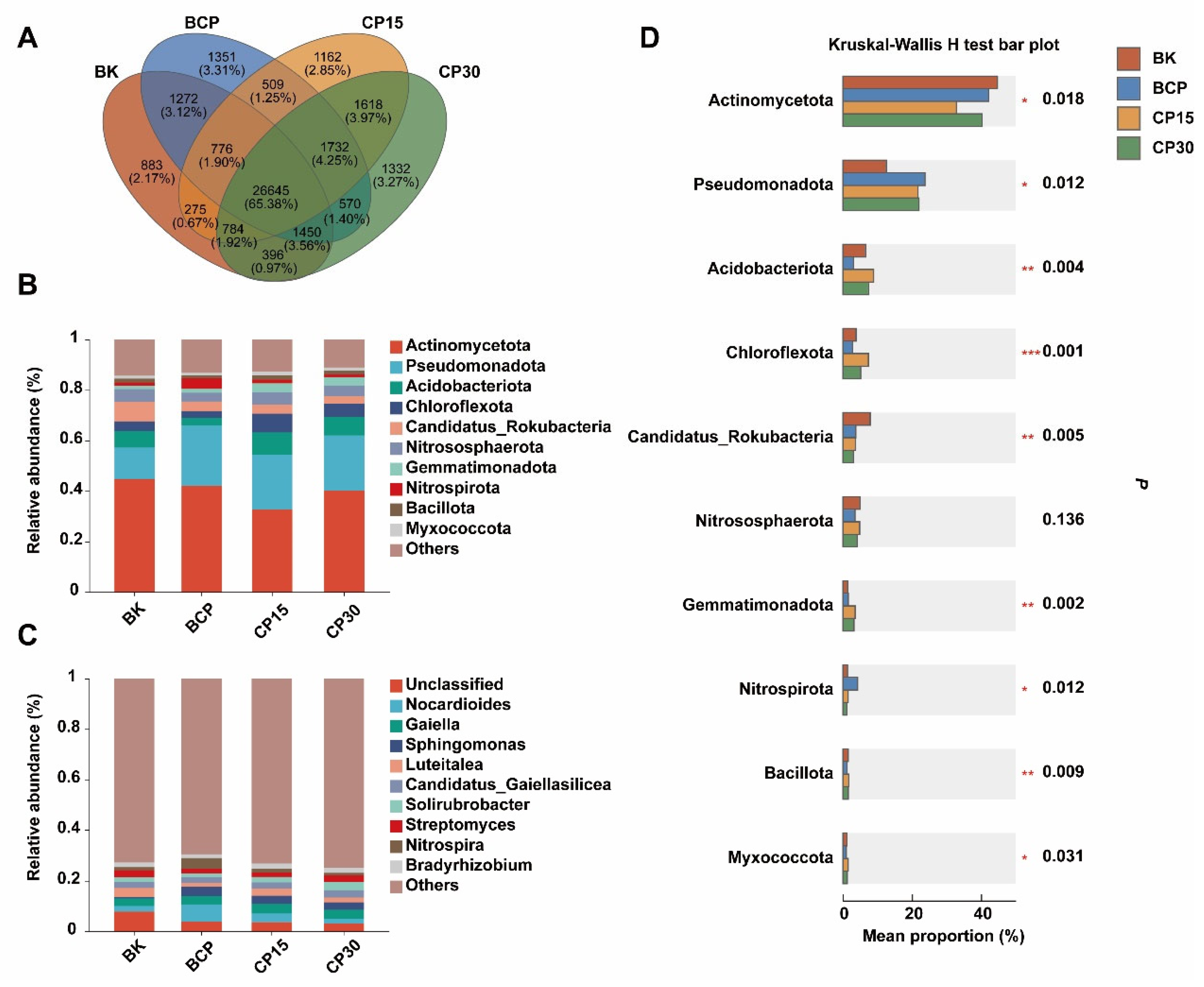

3.2. Effect of Forest Soil Amendment on Microbial Community Composition

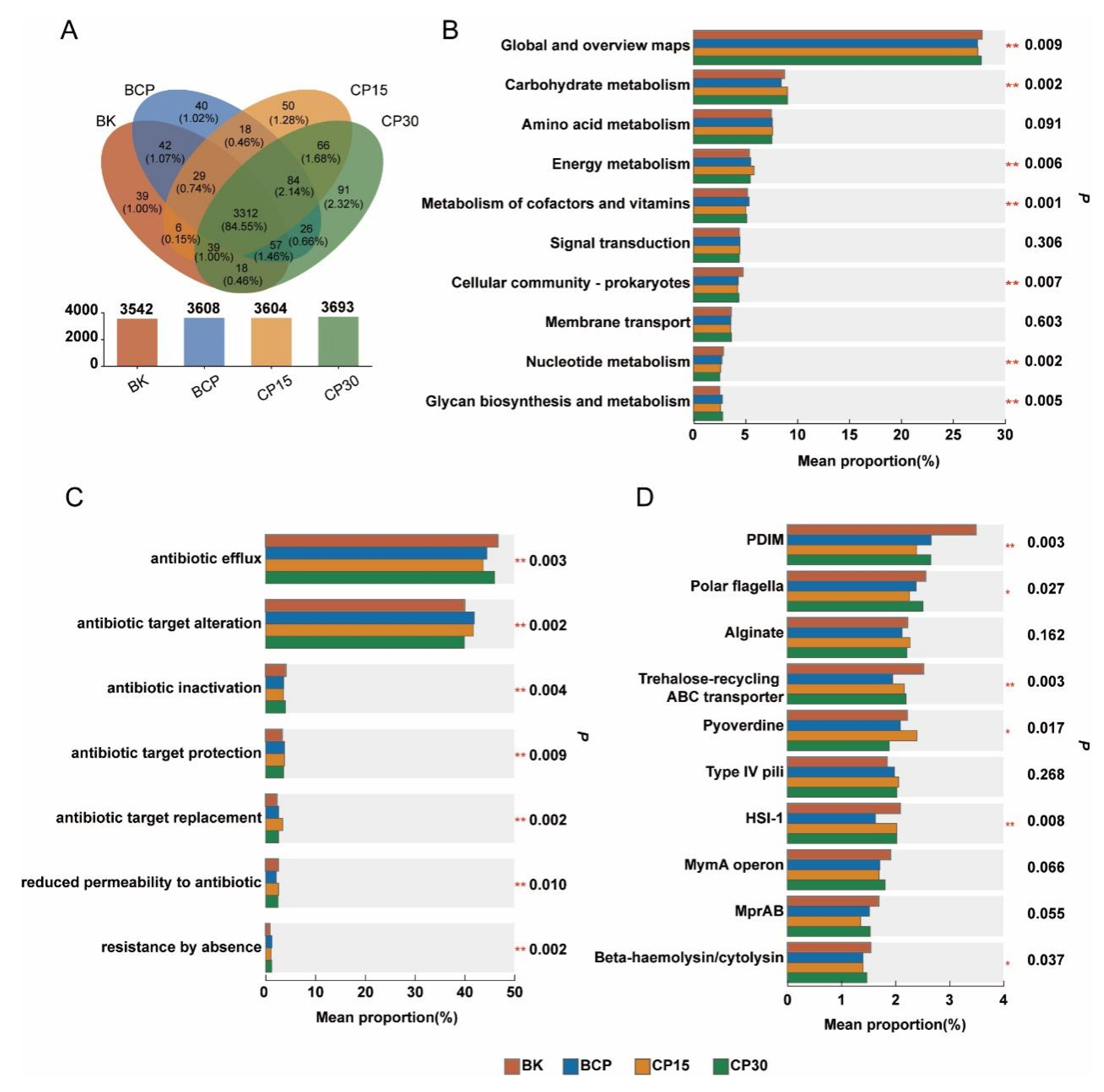

3.3. Effect of Forest Soil Amendment on the Composition of Microbial Functional Genes

3.4. Effect of Forest Soil Amendment on the Composition of Microbial Functional Pathways, Antibiotic Resistance Genes, and Virulence Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Long-Term Continuous Cropping Significantly Alters the Structure and Function of Soil Microbial Communities

4.2. Forest Soil Amendment Significantly Restores Microbial Functional Potential and Diversity

4.3. Practical Implications and Future Prospects for Sustainable Agriculture

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, T.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Liu, K. Cropping systems in agriculture and their impact on soil health—A review. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 23, e01118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, W.; Xu, Y.; Hao, F.; Wang, X.; Siyang, C.; Lin, C. Effect of long-term agricultural cultivation and land use conversion on soil nutrient contents in the Sanjiang Plain. CATENA 2013, 104, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Krupnik, T.J.; Timsina, J.; Mahboob, M.G.; Chaki, A.K.; Farooq, M.; Bhatt, R.; Fahad, S.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Agricultural Land Degradation: Processes and Problems Undermining Future Food Security. In Environment, Climate, Plant and Vegetation Growth; Fahad, S., Hasanuzzaman, M., Alam, M., Ullah, H., Saeed, M., Ali Khan, I., Adnan, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 17–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth, A.J.; Owens, P.R.; Allen, F.L. Long-term cropping systems management influences soil strength and nutrient cycling. Geoderma 2020, 361, 114062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Guan, Z.; Liu, Q.; Hu, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, B.; Huang, L.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Han, M.; et al. Chapter Four-Obstacles in continuous cropping: Mechanisms and control measures. In Advances in Agronomy; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; Volume 179, pp. 205–256. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, S.; Zhu, B.; Yin, R.; Wang, M.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, D.; Chen, X.; Kardol, P.; Liu, M. Organic fertilization promotes crop productivity through changes in soil aggregation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 165, 108533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triberti, L.; Nastri, A.; Baldoni, G. Long-term effects of crop rotation, manure and mineral fertilisation on carbon sequestration and soil fertility. Eur. J. Agron. 2016, 74, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Dai, H.; He, Y.; Liang, T.; Zhai, Z.; Zhang, S.; Hu, B.; Cai, H.; Dai, B.; Xu, Y.; et al. Continuous cropping system altered soil microbial communities and nutrient cycles. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1374550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.-Z.; Zhao, Q.; Huang, X.-Y.; Huang, K.-F. Effect of continuous cropping on the rhizosphere soil and growth of common buckwheat. Plant Prod. Sci. 2020, 23, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Jiang, C.; Riaz, M.; Yu, F.; Dong, Q.; Yan, Y.; Zu, C.; Zhou, C.; Wang, J.; Shen, J. Impacts of continuous cropping on soil fertility, microbial communities, and crop growth under different tobacco varieties in a field study. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2025, 37, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Lu, X.; Zhang, P.; Sun, J.; Cong, B.; Sa, R.; He, D. Effects of continuous cropping on bacterial community diversity and soil metabolites in soybean roots. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1534809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Li, C.; Song, X.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Q.; Zheng, R.; Li, J.; Zhang, P.; Liu, X. Impacts of continuous and rotational cropping practices on soil chemical properties and microbial communities during peanut cultivation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Feng, C.; Jiang, H.; Chen, Y.; Ding, M.; Dai, H.; Zhai, Z.; Yang, M.; Liang, T.; Zhang, Y. Effects of long-term continuous cropping on microbial community structure and function in tobacco rhizosphere soil. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1496385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yue, L.; Ye, A.; Xie, X.; Zhang, M.; Tian, Y.; Liu, Y.; Turatsinze, A.N.; Constantine, U.; et al. Impacts of continuous cropping on the rhizospheric and endospheric microbial communities and root exudates of Astragalus mongholicus. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Wei, L.; Lv, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, Z.; Ge, T.; Zhang, W. Long-term bioorganic and organic fertilization improved soil quality and multifunctionality under continuous cropping in watermelon. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 359, 108721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, W.; Jia, W.; Xu, Z.; Dang, B.; Shao, H.; Qiu, K.; Han, D. Combined use of green fertilizer and soil conditioner improves soil physicochemical properties, microbial community structure and tobacco quality in continuous cropping. Ann. Microbiol. 2025, 75, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Peng, T.; Guo, Y.; Wen, S.; Ji, L.; Luo, Z. Forest succession improves the complexity of soil microbial interaction and ecological stochasticity of community assembly: Evidence from Phoebe bournei-dominated forests in subtropical regions. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1021258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zi, H.; Sonne, C.; Li, X. Microbiome sustains forest ecosystem functions across hierarchical scales. Eco-Environ. Health 2023, 2, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Wang, W.; Yao, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Niu, B. Microbial interactions within beneficial consortia promote soil health. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 900, 165801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.; Liu, Y.; Peng, S.; Yin, H.; Meng, D.; Tao, J.; Gu, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, S.; Xiao, N.; et al. Soil potentials to resist continuous cropping obstacle: Three field cases. Environ. Res. 2021, 200, 111319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Fu, L.; Song, Y.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, H.; Wen, D.; Yang, N.; Wang, X.; Yue, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Effects of continuous cucumber cropping on crop quality and soil fungal community. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, S.; Xiong, X.; Tan, L.; Deng, Y.; Du, X.; Yang, X.; Hu, Q. Soil microbial community assembly and stability are associated with potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) fitness under continuous cropping regime. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1000045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Wang, G.; Cheng, Y.; Shi, P.; Yang, C.; Yang, H.; Xu, Z. Soil acidification in continuously cropped tobacco alters bacterial community structure and diversity via the accumulation of phenolic acids. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, L.; Liu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Shang, J.; Wei, Y.; Tan, Y.; Zi, F. Interactions Between Phenolic Acids and Microorganisms in Rhizospheric Soil From Continuous Cropping of Panax notoginseng. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 791603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Tan, L.; Zhang, F.; Gale, W.J.; Cheng, Z.; Sang, W. Duration of continuous cropping with straw return affects the composition and structure of soil bacterial communities in cotton fields. Can. J. Microbiol. 2017, 64, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Lashari, M.S.; Liu, X.; Ji, H.; Li, L.; Zheng, J.; Kibue, G.W.; Joseph, S.; Pan, G. Changes in soil microbial community structure and enzyme activity with amendment of biochar-manure compost and pyroligneous solution in a saline soil from Central China. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2015, 70, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.; He, J.; Zhou, Z.; Xia, L.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Chu, H.; Liu, W.; et al. Organic amendments enhance soil microbial diversity, microbial functionality and crop yields: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 829, 154627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastida, F.; Eldridge, D.J.; García, C.; Kenny Png, G.; Bardgett, R.D.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M. Soil microbial diversity–biomass relationships are driven by soil carbon content across global biomes. ISME J. 2021, 15, 2081–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, K.; Yang, J.; Zeng, D.; Mo, L.; Pu, G. Nitrogen-cycling microbial diversity and function in tiankengs at different evolutionary stages. CATENA 2025, 254, 108969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, A.; Serpa, D.; Santos, A.K.; Gomes, A.P.; Keizer, J.J.; Oliveira, B.R.F. Effects of different amendments on the quality of burnt eucalypt forest soils—A strategy for ecosystem rehabilitation. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 320, 115766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Li, L.; Friman, V.-P.; Guo, J.; Guo, S.; Shen, Q.; Ling, N. Organic amendments increase crop yields by improving microbe-mediated soil functioning of agroecosystems: A meta-analysis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 124, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Y.-X.; Ding, W.-L.; Zhou, Y.-Q.; Li, Y. Influence of Panax ginseng Continuous Cropping on Metabolic Function of Soil Microbial Communities. Chin. Herb. Med. 2012, 4, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, T.; Yuan, Z.; Gustave, W.; Luan, T.; He, L.; Jia, Z.; Zhao, X.; Wang, S.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, X.; et al. Challenges of continuous cropping in Rehmannia glutinosa: Mechanisms and mitigation measures. Soil Environ. Health 2025, 3, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarauer, J.L.; Coleman, M.D. Microbial communities of biochar amended forest soils in northwestern USA. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 188, 104875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Mao, L.; Chen, B. Driving forces linking microbial community structure and functions to enhanced carbon stability in biochar-amended soil. Environ. Int. 2019, 133, 105211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Guan, P.; Hao, C.; Yang, J.; Xie, Z.; Wu, D. Changes in assembly processes of soil microbial communities in forest-to-cropland conversion in Changbai Mountains, northeastern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 818, 151738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.-J.; Ren, X.-Y.; Zhou, Z.-Z.; Zhu, D.; Zhu, Y.-G. Forest-to-Cropland Conversion Reshapes Microbial Hierarchical Interactions and Degrades Ecosystem Multifunctionality at a National Scale. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 11027–11040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldrian, P.; Kolařík, M.; Štursová, M.; Kopecký, J.; Valášková, V.; Větrovský, T.; Žifčáková, L.; Šnajdr, J.; Rídl, J.; Vlček, Č.; et al. Active and total microbial communities in forest soil are largely different and highly stratified during decomposition. ISME J. 2012, 6, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Song, X.; Wang, K.; He, Z.; Pan, Y.; Li, J.; Hai, X.; Dong, L.; Shangguan, Z.; Deng, L. Changes in soil microbial metabolic activity following long-term forest succession on the central Loess Plateau, China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 723–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Meng, Z.; Xu, R.; Duoji, D.; Zhang, J.; He, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; et al. Soil microbial network complexity predicts ecosystem function along elevation gradients on the Tibetan Plateau. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 172, 108766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, A.A.; Haq, S.; Bhat, R.A. Actinomycetes benefaction role in soil and plant health. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 111, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lu, P.; Feng, S.; Hamel, C.; Sun, D.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Gan, G.Y. Strategies to improve soil health by optimizing the plant–soil–microbe–anthropogenic activity nexus. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 359, 108750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Tang, X.; Ye, W.; Cao, H.; Shen, H. Soil microbial community structure, function and network along a mangrove forest restoration chronosequence. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 913, 169704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrunalini, K.; Behera, B.; Jayaraman, S.; Abhilash, P.C.; Dubey, P.K.; Swamy, G.N.; Prasad, J.V.N.S.; Rao, K.V.; Krishnan, P.; Pratibha, G.; et al. Nature-based solutions in soil restoration for improving agricultural productivity. Land Degrad. Dev. 2022, 33, 1269–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Hu, X.; Zhao, D.; Wang, Y.; Qu, J.; Tao, Y.; Kang, Z.; Yu, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. Harnessing microbial biofilms in soil ecosystems: Enhancing nutrient cycling, stress resilience, and sustainable agriculture. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Song, Y.; An, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhong, G. Soil Microorganisms: Their Role in Enhancing Crop Nutrition and Health. Diversity 2024, 16, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatments | BK | BCP | CP15 | CP30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.18 a | 6.61 a | 7.17 a | 6.62 a |

| Soil organic matter (g/kg) | 16.98 a | 12.54 b | 13.68 b | 16.39 a |

| Total nitrogen (g/kg) | 1.07 ab | 0.86 b | 0.84 b | 1.31 a |

| Total phosphorus (g/kg) | 0.97 a | 0.79 b | 0.55 c | 0.75 b |

| Total potassium(g/Kg) | 10.30 b | 5.95 c | 5.32 c | 14.62 a |

| Alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen (g/kg) | 0.12 a | 0.06 b | 0.09 b | 0.14 a |

| Olsen phosphorus (mg/kg) | 7.65 b | 4.06 b | 21.55 a | 20.78 a |

| Available potassium (mg/kg) | 131.56 a | 102.69 b | 80.66 c | 154.96 a |

| Sugarcane yield (t/ha) | / | 117.30 a | 78.60 b | 81.60 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, R.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, G.; Zhao, P.; Deng, J. Microbial Metagenomics Evidence Reveals Forest Soil Amendment Contributes to Increased Sugarcane Yields in Long-Term Cropping Systems. Agronomy 2026, 16, 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010122

Li R, Zhang R, Zhang Z, Tang G, Zhao P, Deng J. Microbial Metagenomics Evidence Reveals Forest Soil Amendment Contributes to Increased Sugarcane Yields in Long-Term Cropping Systems. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):122. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010122

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Rudan, Ruli Zhang, Zhongfu Zhang, Guolei Tang, Peifang Zhao, and Jun Deng. 2026. "Microbial Metagenomics Evidence Reveals Forest Soil Amendment Contributes to Increased Sugarcane Yields in Long-Term Cropping Systems" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010122

APA StyleLi, R., Zhang, R., Zhang, Z., Tang, G., Zhao, P., & Deng, J. (2026). Microbial Metagenomics Evidence Reveals Forest Soil Amendment Contributes to Increased Sugarcane Yields in Long-Term Cropping Systems. Agronomy, 16(1), 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010122