Thermal Dynamics of Xylem and Soil–Root Temperatures in Olive and Almond Trees and Their Relationship with Air Temperature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

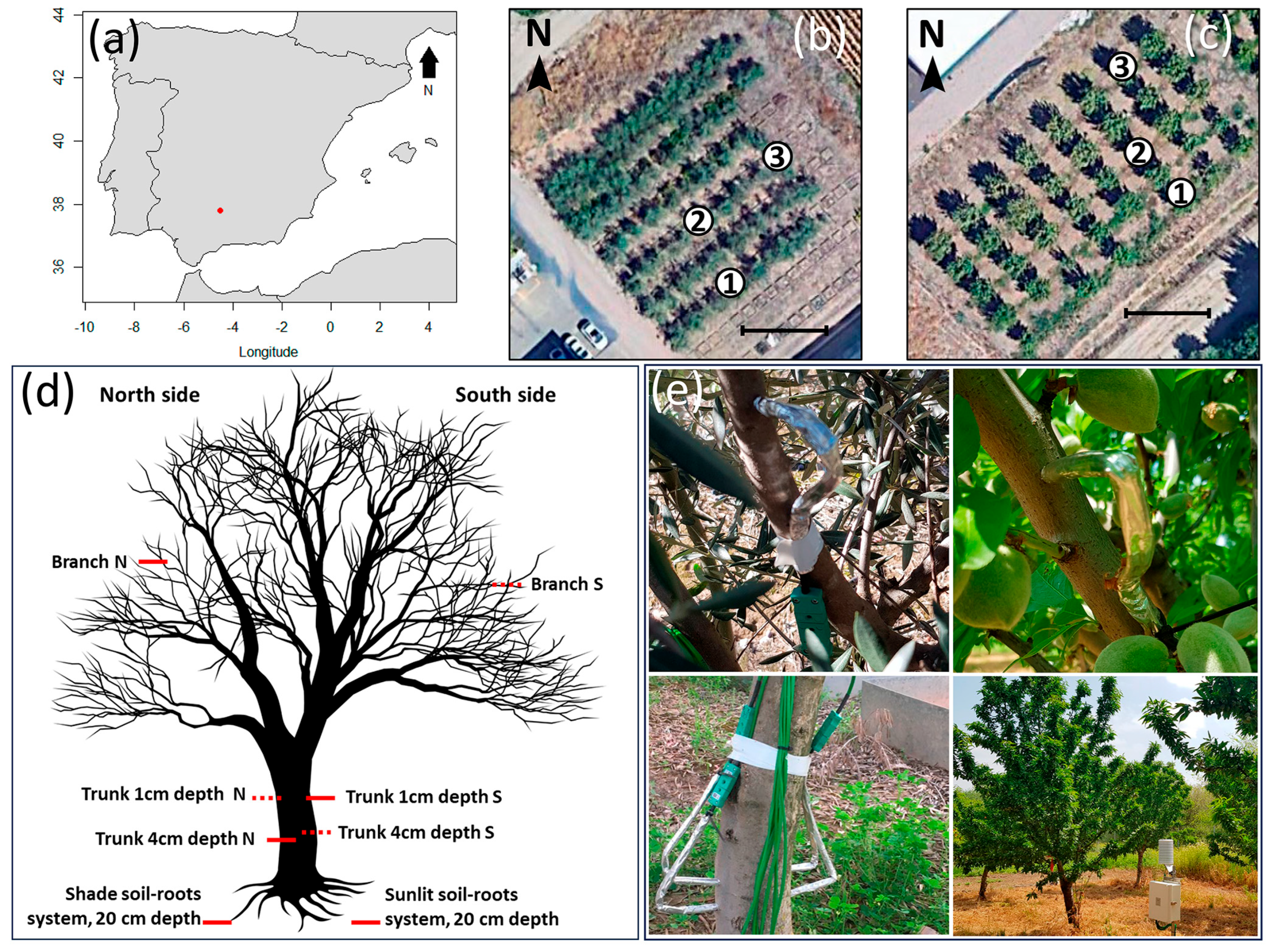

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Temperature Measurements

2.3. Data Analyses

3. Results

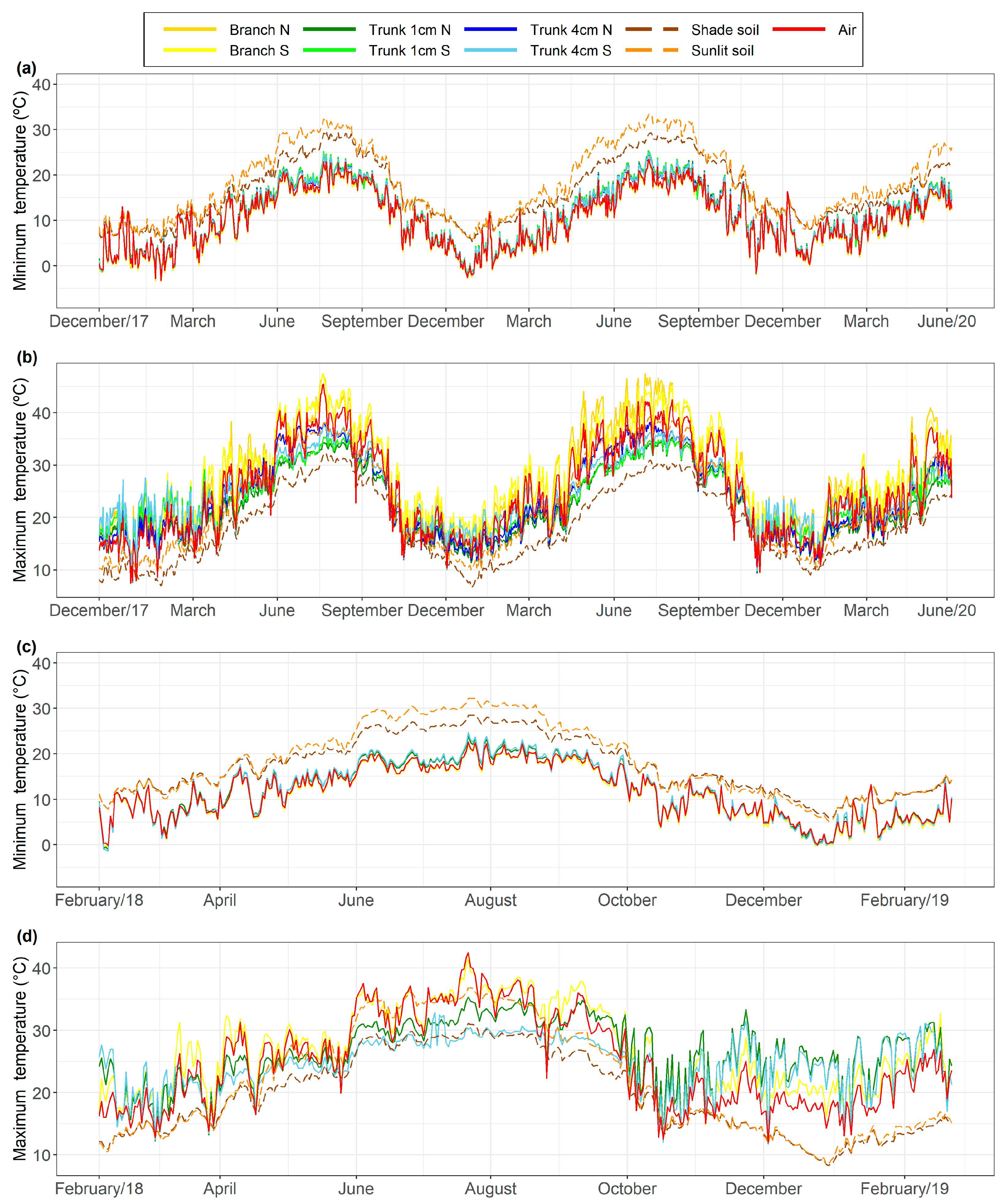

3.1. Temporal Dynamics of Sensor Monthly Average Temperature and Its Relationship with Air Temperature

3.1.1. Air Temperatures

3.1.2. Xylem Temperatures

3.1.3. Soil Temperature

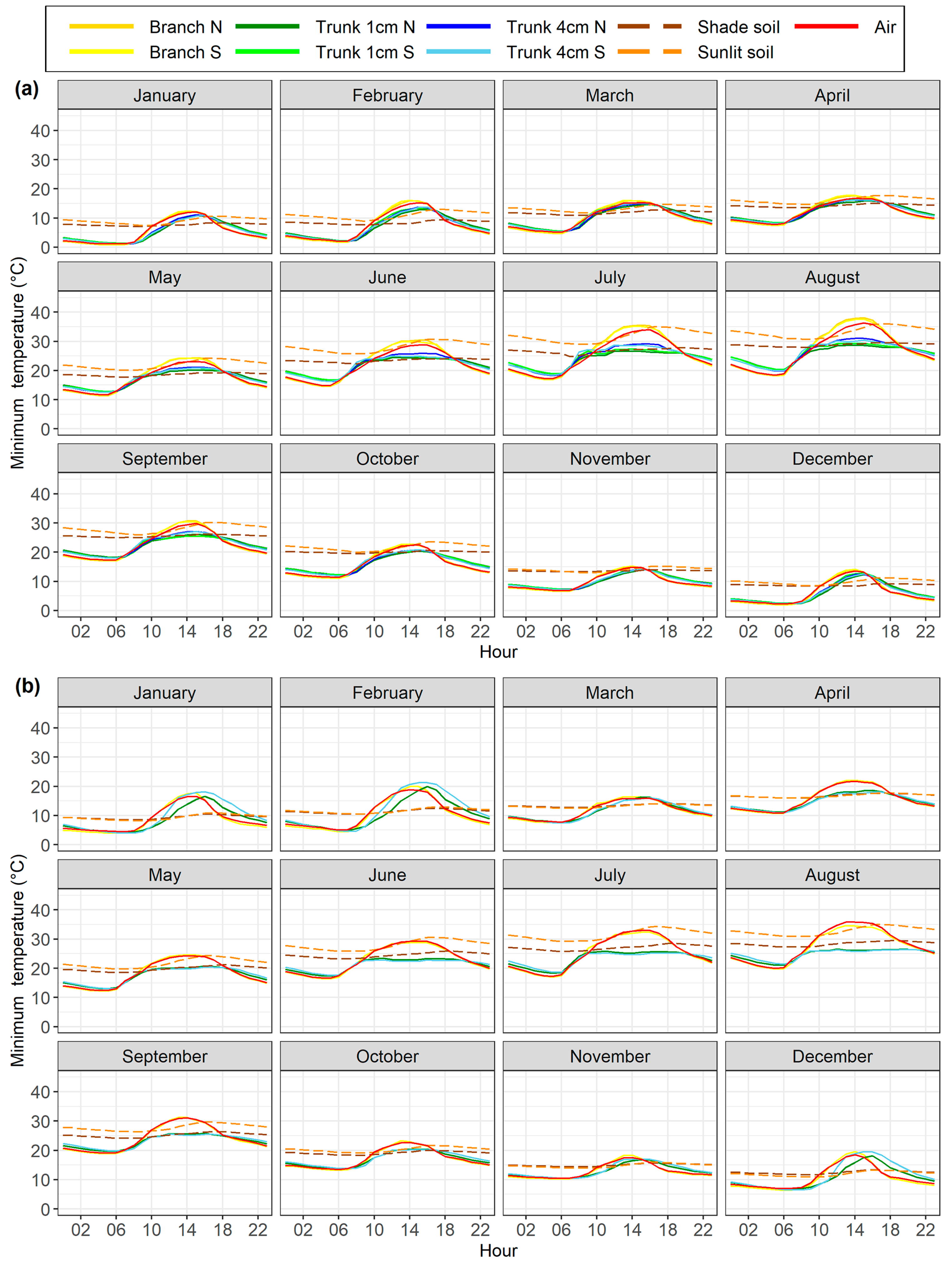

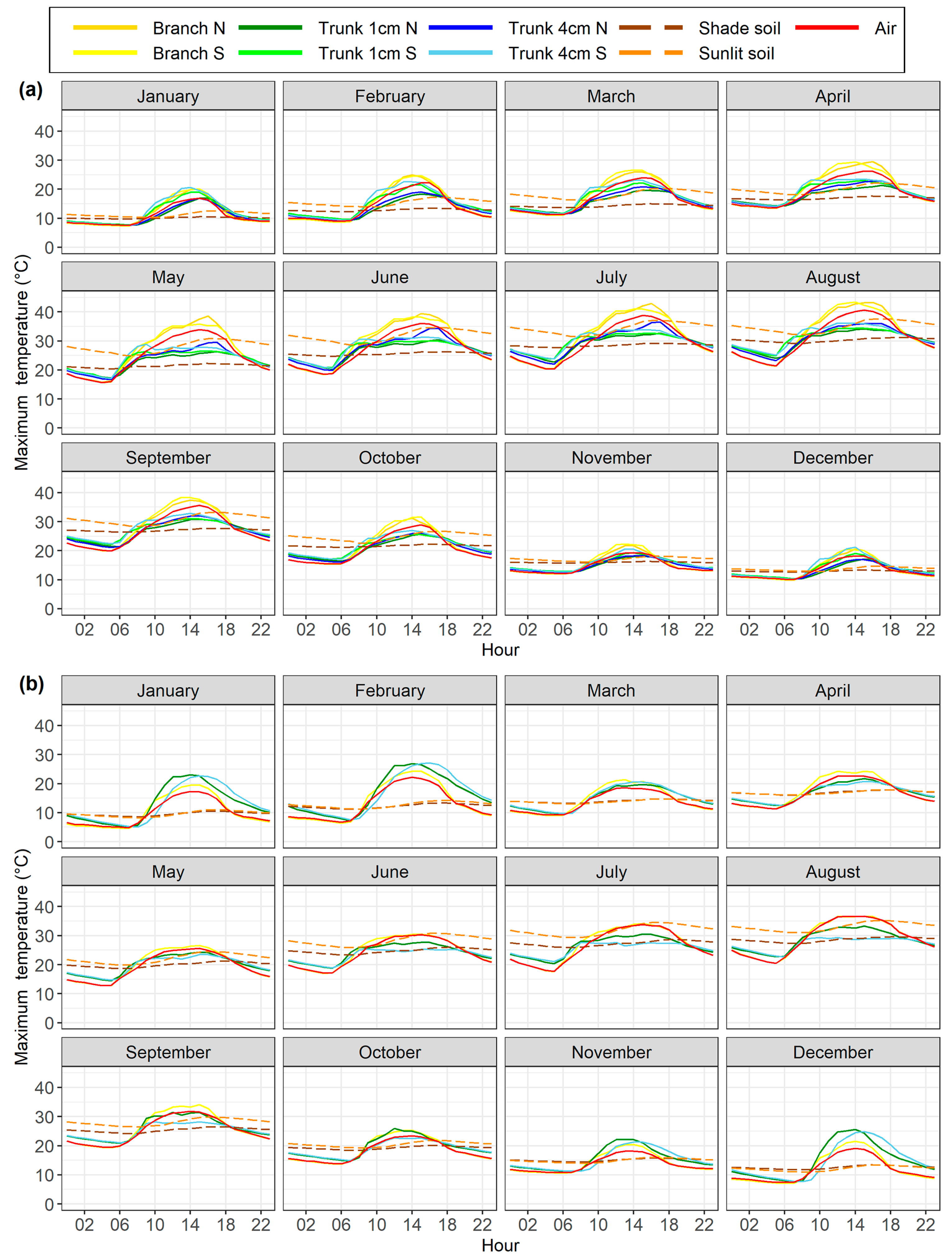

3.2. Seasonal Relationships Between Air and Sensor Temperatures

3.2.1. Minimum Temperatures

3.2.2. Maximum Temperatures

4. Discussion

4.1. Internal Temperature Dynamics and Tree Physiology

4.2. Soil Thermal Behavior

4.3. Potential Implications for Plant-Associated Pathogens

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Data: Crops and Livestock Products; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2022; Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- De Aranzabal, I.; Schmitz, M.F.; Aguilera, P.; Pineda, F.D. Modelling of landscape changes derived from the dynamics of socio-ecological systems: A case of study in a semiarid Mediterranean landscape. Ecol. Indic. 2008, 8, 672–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochhar, S.L.; Gujral, S.K. Plant Physiology: Theory and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mahan, J.R.; McMichael, B.L.; Wanjura, D.F. Methods for reducing the adverse effects of temperature stress on plants: A review. Environ. Exp. Bot. 1995, 35, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockfors, J. Temperature variations and distribution of living cells within tree stems: Implications for stem respiration modeling and scale-up. Tree Physiol. 2000, 20, 1057–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derby, R.W.; Gates, D.M. The temperature of tree trunks-calculated and observed. Am. J. Bot. 1966, 53, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larcher, W. Temperature stress and survival ability of Mediterranean sclerophyllous plants. Plant Biosyst. 2000, 134, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, D.; Porter, J.R. Temperature, plant development and crop yields. Trends Plant Sci. 1996, 1, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zheng, B.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, T.; Feng, H.; Zhou, J.; Fang, O. Temperature-driven cotton Verticillium wilt: A beta model for risk assessment from laboratory insights to climate scenarios. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 81, 1571–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, E.; Wang, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhao, M.; Zhan, J. Elevating air temperature may enhance future epidemic risk of the plant pathogen Phytophthora infestans. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.T.; Nesmith, D.S. Temperature and crop development. In Modeling Plant and Soil Systems; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 5–29. [Google Scholar]

- Peña Quiñones, A.J.; Hoogenboom, G.; Salazar Gutiérrez, M.R.; Stöckle, C.; Keller, M. Comparison of air temperature measured in a vineyard canopy and at a standard weather station. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234436. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, N.T.; Hanson, P.J. Stem respiration in a closed-canopy upland oak forest. Tree Physiol. 1996, 16, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolai, V. The bark of trees: Thermal properties, microclimate and fauna. Oecologia 1986, 69, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, B.E.; Andresen, J.A. A finite-difference model of temperatures and heat flow within a tree stem. Can. J. For. Res. 2002, 32, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubrecht, D.M.; Helliker, B.R.; Goulden, M.L.; Roberts, D.A.; Still, C.J.; Richardson, A.D. Continuous, long-term, high-frequency thermal imaging of vegetation: Uncertainties and recommended best practices. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2016, 228, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, J.; Warren, L.; Ohlson, G.; Hiers, J.; Shrestha, M.; Mitra, C.; Hill, E.; Bradfield, S.; Ocheltree, T. Applications of low-cost environmental monitoring systems for fine-scale abiotic measurements in forest ecology. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 321, 108973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, S.; Wieser, G.; Bauer, H. Xylem temperatures during winter in conifers at the alpine timberline. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2006, 137, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermunt, B.; Cuddington, K.; Sobek-Swant, S.; Crosthwaite, J.C.; Barry Lyons, D.; Sinclair, B.J. Temperatures experienced by wood-boring beetles in the under-bark microclimate. For. Ecol. Manag. 2012, 269, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bär, A.; Mayr, S. Bark insulation: Ten Central Alpine tree species compared. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 474, 118361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña Quiñones, A.J.; Keller, M.; Salazar Gutierrez, M.R.; Khot, L.; Hoogenboom, G. Comparison between grapevine tissue temperature and air temperature. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 247, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastogeer, K.M.; Tumpa, F.H.; Sultana, A.; Akter, M.A.; Chakraborty, A. Plant microbiome—An account of the factors that shape community composition and diversity. Curr. Plant Biol. 2020, 23, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunjan, M.S.; Lore, J.S. Climate change: Impact on plant pathogens, diseases, and their management. In Crop Protection Under Changing Climate; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Katan, J. Soil temperature interactions with the biotic components of vascular wilt diseases. In Vascular Wilt Diseases of Plants: Basic Studies and Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1989; pp. 353–366. [Google Scholar]

- Feil, H.; Purcell, A.H. Temperature-dependent growth and survival of Xylella fastidiosa in vitro and in potted grapevines. Plant Dis. 2001, 85, 1230–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbarao, K. Interactive effects of broccoli residue and temperature on Verticillium dahliae microsclerotia in soil and on wilt in cauliflower. Phytopathology 1996, 86, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, R.; Lucena, C.; Trapero-Casas, J.L.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Navas-Cortés, J.A. Soil temperature determines the reaction of olive cultivars to Verticillium dahliae pathotypes. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henneberger, T.S.M.; Stevenson, K.L.; Britton, K.O.; Chang, C.J. Distribution of Xylella fastidiosa in sycamore associated with low temperature and host resistance. Plant Dis. 2004, 88, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testi, L.; Villalobos, F.J.; Orgaz, F. Evapotranspiration of a young irrigated olive orchard in southern Spain. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2004, 121, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Bernal, Á.; Alcántara, E.; Testi, L.; Villalobos, F.J. Spatial sap flow and xylem anatomical characteristics in olive trees under different irrigation regimes. Tree Physiol. 2010, 30, 1536–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Y.; Cohen, S.; Cantuarias-Aviles, T.; Schiller, G. Variations in the radial gradient of sap velocity in trunks of forest and fruit trees. Plant Soil 2008, 305, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadezhdina, N.; Nadezhdin, V.; Ferreira, M.I.; Pitacco, A. Variability with xylem depth in sap flow in trunks and branches of mature olive trees. Tree Physiol. 2007, 27, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenberth, K.E. What are the seasons? Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1983, 64, 1276–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, Version 4.0.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- de Mendiburu, F. agricolae: Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research, Version 1.3-5 R Package; 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=agricolae (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Hothorn, T.; Bretz, F.; Westfall, P. Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom. J. 2008, 50, 346–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenth, R.V. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means, Version 1.8.5 R Package; 2024. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/emmeans/index.html (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Gansert, D.; Burgdorf, M.; Lösch, R. A novel approach to the in situ measurement of oxygen concentrations in the sapwood of woody plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2001, 24, 1055–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, B.L. Patterns of xylem variation within a tree and their hydraulic and mechanical consequences. In Plant Stems; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 125–149. [Google Scholar]

- Quick, D.D. Continuous Measurements of Water Status in Deeply Rooted Southern California Chaparral Shrub Species. Master’s Thesis, California State University, Fullerton, CA, USA, 2016. Available online: https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/concern/theses/pk02cc875 (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Lindroth, A.; Mölder, M.; Lagergren, F. Heat storage in forest biomass improves energy balance closure. Biogeosciences 2010, 7, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trcala, M.; Čermák, J. Nonlinear finite element analysis of thermal inertia in heat-balance sap flow measurement. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2014, 76, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunert, N.; Mercado Cárdenas, A. Effects of xylem water transport on CO2 efflux of woody tissue in a tropical tree, Amazonas State, Brazil. Hoehnea 2012, 39, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, F.; Rocheteau, A. Influence of natural temperature gradients on measurements of xylem sap flow with thermal dissipation probes. 1. Field observations and possible remedies. Tree Physiol. 2002, 22, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.M.; Allen, S.J. Measurement of sap flow in plant stems. J. Exp. Bot. 1996, 47, 1833–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatarinov, F.A.; Kučera, J.; Cienciala, E. The analysis of physical background of tree sap flow measurement based on thermal methods. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2005, 16, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavelka, M.; Acosta, M.; Marek, M.; Kutsch, W.L.; Janous, D. Dependence of the Q10 values on the depth of the soil temperature measuring point. Plant Soil 2007, 292, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Gao, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, X.; Wu, P. Sloping land use affects soil moisture and temperature in the Loess Hilly region of China. Agronomy 2020, 10, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, C.; González Sotelino, L.; Journée, M. Quality control of 10-min soil temperatures data at RMI. Adv. Sci. Res. 2015, 12, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pregitzer, K.S.; King, J.S.; Burton, A.J.; Brown, S.E. Responses of tree fine roots to temperature. New Phytol. 2000, 147, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román Ecija, M.; Landa, B.B.; Testi, L.; Navas Cortés, J.A. Extreme temperature differentially affects growth and survival of Xylella fastidiosa strains. In Proceedings of the 3rd European Conference on Xylella fastidiosa, Online, 29–30 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Klosterman, S.J.; Atallah, Z.K.; Vallad, G.E.; Subbarao, K.V. Diversity, pathogenicity, and management of Verticillium species. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2009, 47, 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amanifar, N.; Taghavi, M.; Salehi, M. Xylella fastidiosa from almond in Iran: Overwinter recovery and effects of antibiotics. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2016, 55, 337–345. [Google Scholar]

- Saponari, M.; Boscia, D.; Altamura, G.; Loconsole, G.; Zicca, S.; D’Attoma, G.; Morelli, M.; Palmisano, F.; Saponari, A.; Tavano, D.; et al. Isolation and pathogenicity of Xylella fastidiosa associated to the olive quick decline syndrome in southern Italy. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| T/ Crop/Month | T Air | T Soil Sunlit | T Soil Shade | T Branch N | T Branch S | T Trunk 1 cm N | T Trunk 1 cm S | T Trunk 4 cm N | T Trunk 4 cm S | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum temperatures | ||||||||||||||||||

| Olive orchard | ||||||||||||||||||

| January | 3.24 | b | 8.72 | a | 8.36 | a | 2.97 | b | 3.05 | b | 3.72 | b | 3.73 | b | 3.57 | b | 3.58 | b |

| February | 4.26 | b | 10.88 | a | 9.69 | a | 3.94 | b | 4.04 | b | 4.84 | b | 4.80 | b | 4.65 | b | 4.67 | b |

| March | 7.01 | cd | 13.84 | a | 12.21 | b | 6.62 | d | 6.75 | cd | 7.72 | c | 7.58 | cd | 7.50 | cd | 7.51 | cd |

| April | 9.80 | cd | 16.17 | a | 14.74 | b | 9.41 | d | 9.53 | d | 10.64 | c | 10.59 | c | 10.42 | cd | 10.41 | cd |

| May | 13.20 | d | 22.43 | a | 19.06 | b | 12.88 | d | 13.04 | d | 14.51 | c | 14.45 | c | 14.21 | c | 14.23 | c |

| June | 15.84 | d | 26.72 | a | 22.96 | b | 15.56 | d | 15.62 | d | 17.57 | c | 17.66 | c | 17.16 | c | 17.21 | c |

| July | 18.37 | d | 30.05 | a | 26.08 | b | 18.09 | d | 18.04 | d | 20.17 | c | 20.24 | c | 19.71 | c | 19.79 | c |

| August | 19.58 | d | 31.16 | a | 28.15 | b | 19.26 | d | 19.31 | d | 21.42 | c | 21.43 | c | 20.92 | c | 20.96 | c |

| September | 18.05 | de | 26.81 | a | 25.38 | b | 17.74 | e | 17.79 | e | 19.16 | c | 18.76 | cd | 18.85 | cd | 18.83 | cd |

| October | 12.35 | bc | 20.89 | a | 20.06 | a | 12.08 | c | 12.14 | c | 13.45 | b | 13.38 | b | 13.16 | bc | 13.11 | bc |

| November | 8.24 | b | 14.27 | a | 14.32 | a | 7.95 | b | 8.04 | b | 8.98 | b | 8.87 | b | 8.77 | b | 8.79 | b |

| December | 5.11 | b | 10.47 | a | 10.36 | a | 4.82 | b | 4.90 | b | 5.62 | b | 5.60 | b | 5.48 | b | 5.47 | b |

| Almond orchard | ||||||||||||||||||

| January | 3.80 | b | 8.15 | a | 8.52 | a | 3.15 | b | 3.76 | b | 3.67 | b | ||||||

| February | 5.28 | b | 10.80 | a | 10.74 | a | 4.70 | b | 5.27 | b | 5.01 | b | ||||||

| March | 7.74 | b | 12.71 | a | 12.90 | a | 7.47 | b | 7.93 | b | 7.74 | b | ||||||

| April | 10.48 | b | 15.95 | a | 15.90 | a | 10.32 | b | 11.01 | b | 10.79 | b | ||||||

| May | 12.15 | d | 19.74 | a | 18.55 | b | 11.90 | d | 12.92 | c | 12.94 | c | ||||||

| June | 16.51 | d | 25.78 | a | 23.26 | b | 16.31 | d | 17.33 | c | 17.56 | c | ||||||

| July | 17.19 | d | 29.22 | a | 25.79 | b | 16.99 | d | 18.32 | c | 18.62 | c | ||||||

| August | 19.94 | d | 30.92 | a | 27.26 | b | 19.75 | d | 21.05 | c | 21.45 | c | ||||||

| September | 18.76 | d | 26.31 | a | 24.06 | b | 18.48 | d | 19.40 | c | 19.60 | c | ||||||

| October | 12.92 | cd | 18.97 | a | 18.15 | b | 12.63 | d | 13.28 | cd | 13.45 | c | ||||||

| November | 9.50 | bc | 13.86 | a | 14.35 | a | 9.16 | c | 9.78 | bc | 9.93 | b | ||||||

| December | 6.52 | cd | 10.84 | b | 11.68 | a | 5.92 | d | 6.41 | c | 6.29 | cd | ||||||

| Maximum temperatures | ||||||||||||||||||

| Olive orchard | ||||||||||||||||||

| January | 15.11 | c | 11.76 | d | 9.59 | e | 17.62 | a | 17.83 | a | 14.58 | c | 16.29 | b | 14.77 | c | 17.80 | a |

| February | 19.52 | c | 14.93 | e | 11.30 | f | 22.07 | ab | 22.60 | a | 16.84 | d | 19.40 | c | 17.53 | d | 20.98 | b |

| March | 20.99 | b | 17.82 | d | 14.05 | e | 23.21 | a | 23.96 | a | 18.16 | cd | 20.38 | b | 19.04 | c | 21.28 | b |

| April | 22.90 | b | 20.06 | de | 16.49 | f | 25.92 | a | 25.96 | a | 19.38 | e | 20.81 | cd | 20.69 | cde | 21.70 | bc |

| May | 29.99 | c | 27.84 | d | 21.01 | g | 34.18 | a | 32.33 | b | 24.51 | f | 25.60 | ef | 27.37 | d | 26.87 | de |

| June | 32.74 | b | 32.44 | b | 25.16 | d | 36.17 | a | 35.26 | a | 28.79 | c | 28.77 | c | 32.20 | b | 29.77 | c |

| July | 37.01 | b | 36.14 | bc | 28.61 | f | 40.23 | a | 39.76 | a | 32.22 | e | 32.17 | e | 35.93 | c | 33.35 | d |

| August | 39.15 | b | 36.92 | c | 30.48 | f | 42.29 | a | 42.16 | a | 33.71 | e | 34.08 | e | 35.60 | d | 35.55 | d |

| September | 33.56 | b | 31.84 | c | 27.07 | e | 35.32 | a | 36.51 | a | 29.77 | d | 30.10 | d | 30.68 | cd | 31.44 | c |

| October | 26.73 | b | 25.36 | bc | 21.58 | d | 28.54 | a | 29.40 | a | 24.00 | c | 24.28 | c | 24.53 | c | 25.34 | bc |

| November | 17.67 | cd | 16.82 | d | 15.29 | e | 19.69 | ab | 20.55 | a | 16.60 | de | 17.44 | cd | 16.86 | d | 18.56 | bc |

| December | 16.41 | bc | 13.14 | d | 11.50 | e | 18.35 | a | 18.72 | a | 15.72 | c | 17.30 | b | 15.78 | c | 18.96 | a |

| Almond orchard | ||||||||||||||||||

| January | 17.44 | c | 11.01 | d | 10.52 | d | 20.03 | b | 23.55 | a | 22.89 | a | ||||||

| February | 21.28 | c | 13.59 | d | 13.00 | d | 23.59 | b | 26.30 | a | 26.55 | a | ||||||

| March | 18.71 | b | 14.55 | c | 14.49 | c | 21.55 | a | 20.15 | ab | 20.71 | a | ||||||

| April | 23.27 | b | 17.85 | d | 17.79 | d | 25.39 | a | 21.92 | c | 20.95 | c | ||||||

| May | 26.14 | b | 24.56 | c | 21.25 | e | 27.29 | a | 24.72 | c | 23.75 | d | ||||||

| June | 30.73 | a | 30.84 | a | 26.03 | c | 31.00 | a | 28.03 | b | 26.15 | c | ||||||

| July | 33.86 | a | 34.52 | a | 28.62 | c | 34.24 | a | 30.63 | b | 28.75 | c | ||||||

| August | 37.05 | a | 35.17 | b | 29.58 | d | 37.26 | a | 33.48 | c | 29.70 | d | ||||||

| September | 31.91 | b | 29.89 | c | 26.54 | e | 34.57 | a | 32.00 | b | 28.64 | d | ||||||

| October | 23.78 | b | 22.05 | c | 20.28 | d | 26.05 | a | 26.64 | a | 23.36 | bc | ||||||

| November | 18.41 | c | 16.04 | d | 15.76 | d | 20.78 | b | 22.94 | a | 21.62 | ab | ||||||

| December | 19.16 | c | 13.40 | d | 13.43 | d | 21.71 | b | 25.90 | a | 24.90 | a | ||||||

| Temperature Crop/Sensor | Season | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winter | Spring | Summer | Autumn | |||||

| Minimum temperatures | ||||||||

| Olive orchard | ||||||||

| Branch N | 9.97 | C d | 10.17 | AB d | 10.60 | A e | 10.38 | BC d |

| Branch S | 10.06 | C d | 10.30 | AB d | 10.63 | A e | 10.45 | BC d |

| Trunk 1 cm N | 10.78 | C c | 11.49 | B c | 12.69 | A c | 11.65 | B c |

| Trunk 1 cm S | 10.77 | C c | 11.41 | B c | 12.74 | A c | 11.46 | B c |

| Trunk 4 cm N | 10.63 | C c | 11.24 | B c | 12.23 | A d | 11.38 | B c |

| Trunk 4 cm S | 10.63 | C c | 11.25 | B c | 12.29 | A d | 11.37 | B c |

| Shade soil | 15.53 | D b | 15.87 | C b | 18.66 | A b | 17.72 | B b |

| Sunlit soil | 16.06 | D a | 18.02 | C a | 22.25 | A a | 18.46 | B a |

| Almond orchard | ||||||||

| Branch N | 10.71 | B c | 11.24 | A c | 11.54 | A d | 11.29 | A d |

| Trunk 1 cm N | 11.27 | C b | 11.94 | B b | 12.76 | A c | 12.02 | B c |

| Trunk 4 cm S | 11.11 | C bc | 11.81 | B b | 13.07 | A c | 12.20 | B c |

| Shade soil | 16.46 | C a | 17.10 | B a | 19.30 | A b | 16.72 | BC b |

| Sunlit soil | 16.10 | C a | 17.41 | B a | 22.51 | A a | 17.59 | B a |

| Maximum temperatures | ||||||||

| Olive orchard | ||||||||

| Branch N | 25.51 | D a | 28.16 | B a | 31.02 | A a | 27.20 | C b |

| Branch S | 25.88 | C a | 27.80 | B a | 30.49 | A a | 28.17 | B a |

| Trunk 1 cm N | 21.92 | B c | 21.07 | C d | 23.07 | A d | 22.81 | A d |

| Trunk 1 cm S | 23.85 | A b | 22.65 | C c | 23.16 | B d | 23.29 | B d |

| Trunk 4 cm N | 22.22 | D c | 22.76 | C c | 26.10 | A b | 23.37 | B d |

| Trunk 4 cm S | 25.43 | A a | 23.67 | C b | 24.37 | B c | 24.46 | B c |

| Shade soil | 17.01 | D e | 17.56 | C e | 19.57 | B e | 20.66 | A e |

| Sunlit soil | 19.47 | D d | 22.30 | C c | 26.67 | A b | 24.03 | B c |

| Almond orchard | ||||||||

| Branch N | 25.94 | B b | 26.36 | C a | 27.61 | A a | 27.31 | A a |

| Trunk 1 cm N | 29.37 | B a | 23.97 | B b | 24.15 | A b | 27.37 | A a |

| Trunk 4 cm S | 28.94 | A a | 23.60 | C b | 21.64 | C c | 24.71 | B b |

| Shade soil | 16.41 | C c | 19.45 | B d | 21.51 | A c | 21.04 | A d |

| Sunlit soil | 16.78 | D c | 20.52 | C c | 26.95 | A a | 22.84 | B c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Román-Écija, M.; Landa, B.B.; Testi, L.; Navas-Cortés, J.A. Thermal Dynamics of Xylem and Soil–Root Temperatures in Olive and Almond Trees and Their Relationship with Air Temperature. Agronomy 2026, 16, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010102

Román-Écija M, Landa BB, Testi L, Navas-Cortés JA. Thermal Dynamics of Xylem and Soil–Root Temperatures in Olive and Almond Trees and Their Relationship with Air Temperature. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010102

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomán-Écija, Miguel, Blanca B. Landa, Luca Testi, and Juan A. Navas-Cortés. 2026. "Thermal Dynamics of Xylem and Soil–Root Temperatures in Olive and Almond Trees and Their Relationship with Air Temperature" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010102

APA StyleRomán-Écija, M., Landa, B. B., Testi, L., & Navas-Cortés, J. A. (2026). Thermal Dynamics of Xylem and Soil–Root Temperatures in Olive and Almond Trees and Their Relationship with Air Temperature. Agronomy, 16(1), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010102