Plant-Driven Effects of Wildflower Strips on Natural Enemy Biodiversity and Pest Suppression in an Agricultural Landscape in Hangzhou, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- How do wildflower strips alter the spatial distribution and diversity of natural enemy communities relative to natural grass strips?

- (2)

- What are the cascading effects of habitat-driven natural enemy changes on pest population dynamics?

- (3)

- Which plant community traits (e.g., species richness, floral phenology) drive natural enemy assembly and pest regulation in wildflower strips?

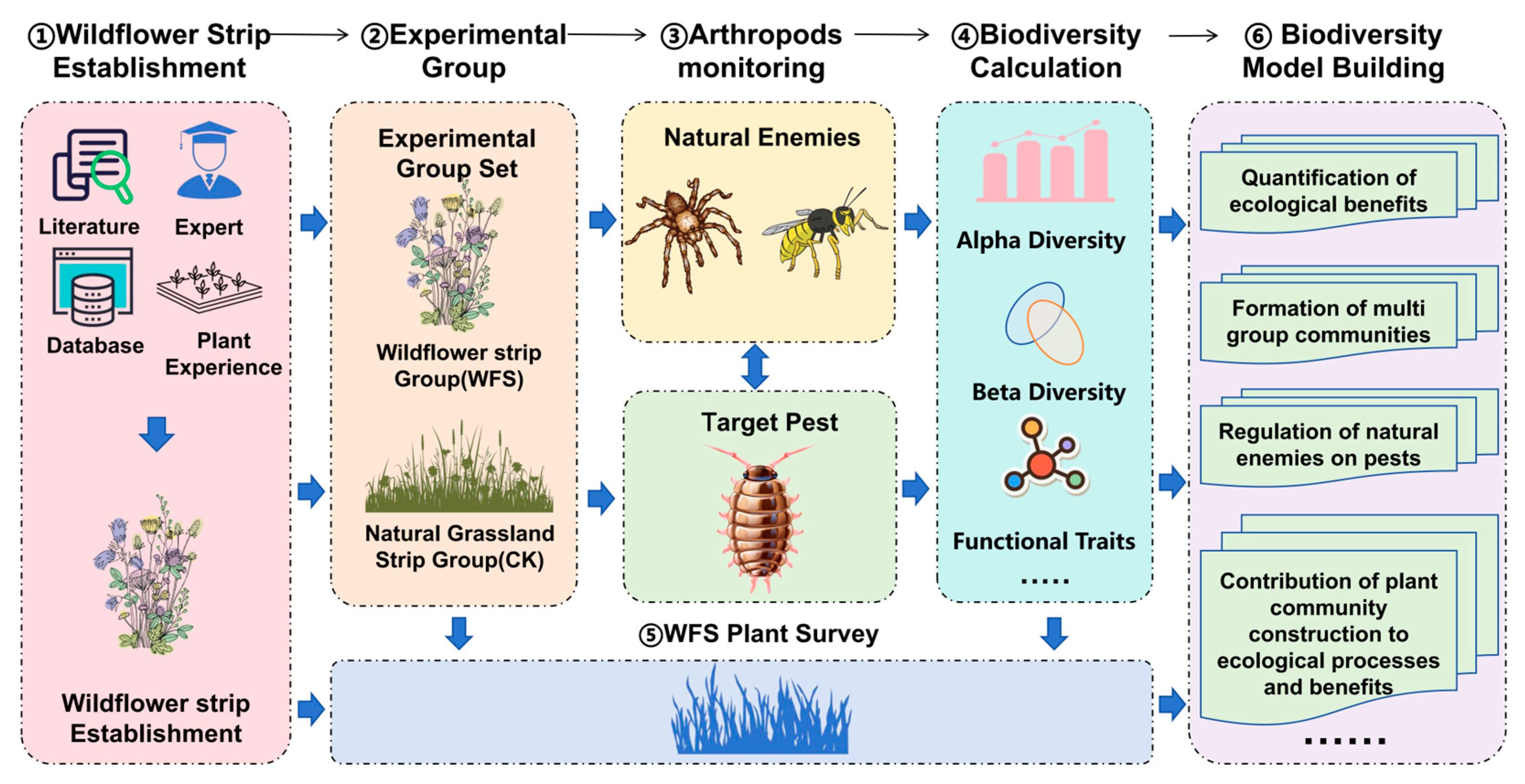

2. Materials and Methods

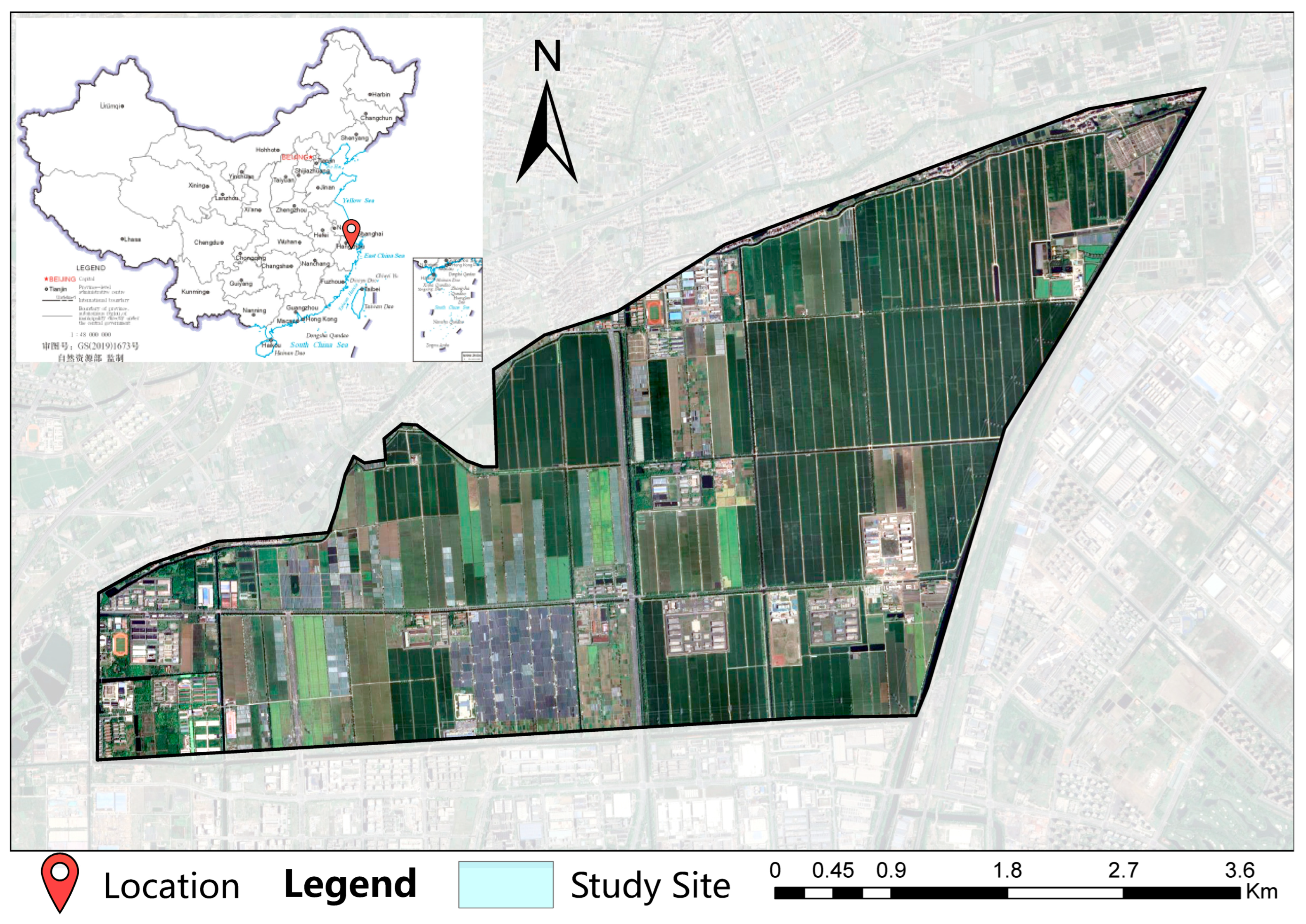

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Experimental Design

- (i)

- Pre-treatment: Glyphosate-isopropylamine (41% SL, 3.5 L/ha) was applied 28 ± 2 days prior, followed by 72-h waterlogging at 5 cm depth to induce weed germination, and subsequent rotary tillage at 15 cm depth. Soil amendment adjusted acidic soil pH to 6.0–6.5 using elemental sulfur and enriched organic matter to 2.3% with composted manure.

- (ii)

- Sowing: Drill methods were employed with 2–3 cm furrow depth and 30 cm row spacing, distributing hydro-primed seeds mixed with vermiculite substrate (1:3 ratio) at 4–6 g/m2. During germination (0–21 days), drip irrigation maintained 18% ± 2% volumetric water content, followed by the farm’s irrigation system delivering 25 mm water twice weekly.

- (iii)

- Post-establishment management: Dynamic thinning was conducted to maintain plant density at 30–35 individuals/m2, with strict prohibition of pesticides and fungicides. Invasive weeds were manually removed quarterly, maintaining a frequency of <5%. The total experiment flow can be seen in Figure 2.

2.3. Natural Enemies and Target Pest Survey

2.3.1. Selection of Target Taxa

2.3.2. Methods for Biodiversity Monitoring

2.4. Functional Traits

2.5. Plant Survey

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Overall Sample Collection

3.1.1. Spider Sample Collection

3.1.2. Parasitic/Predatory Wasp Sample Collection

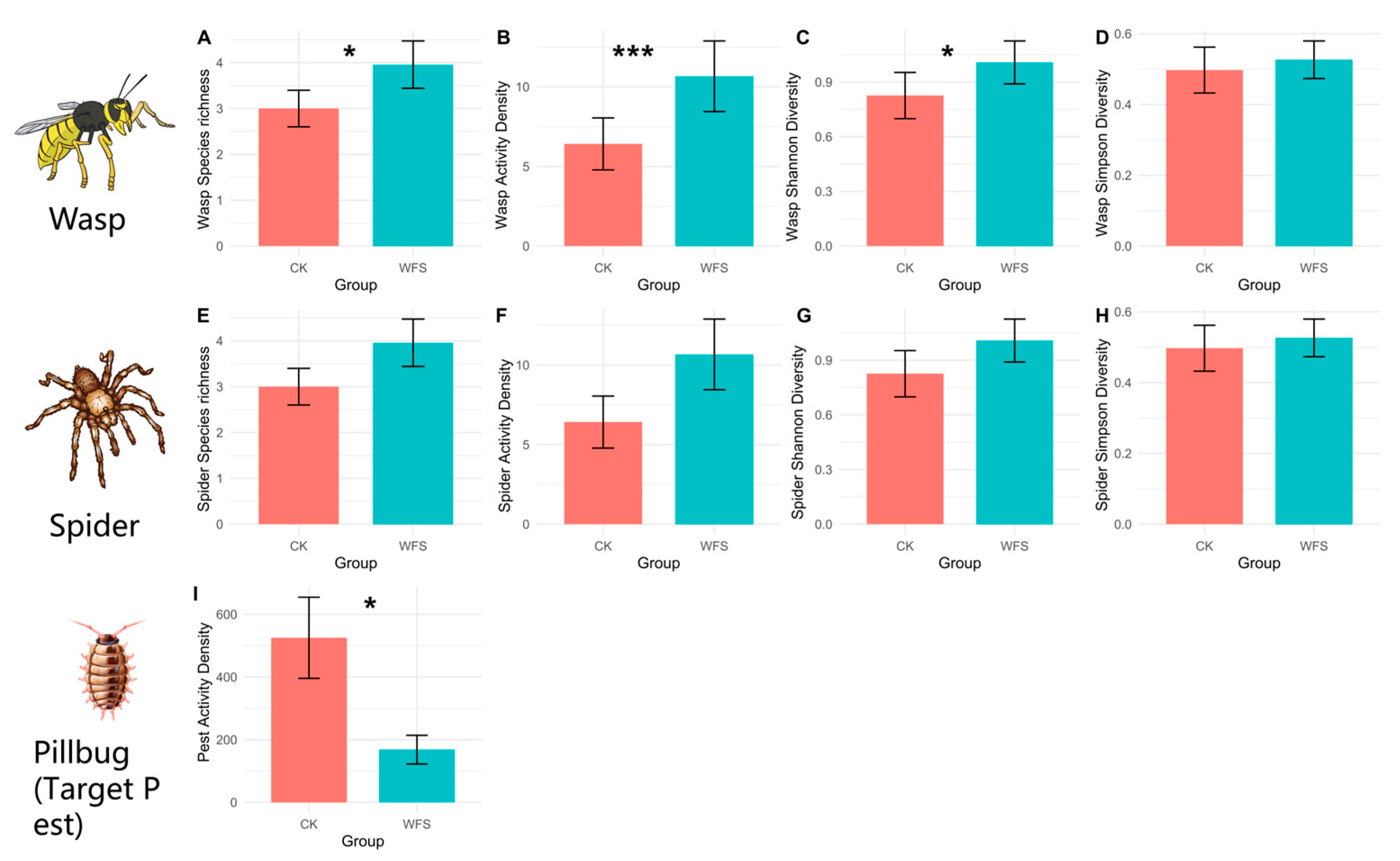

3.2. Differences in Target Taxa Communities Between Wildflower vs. Natural Grass Strip

3.2.1. Alpha Diversity

3.2.2. Beta Diversity

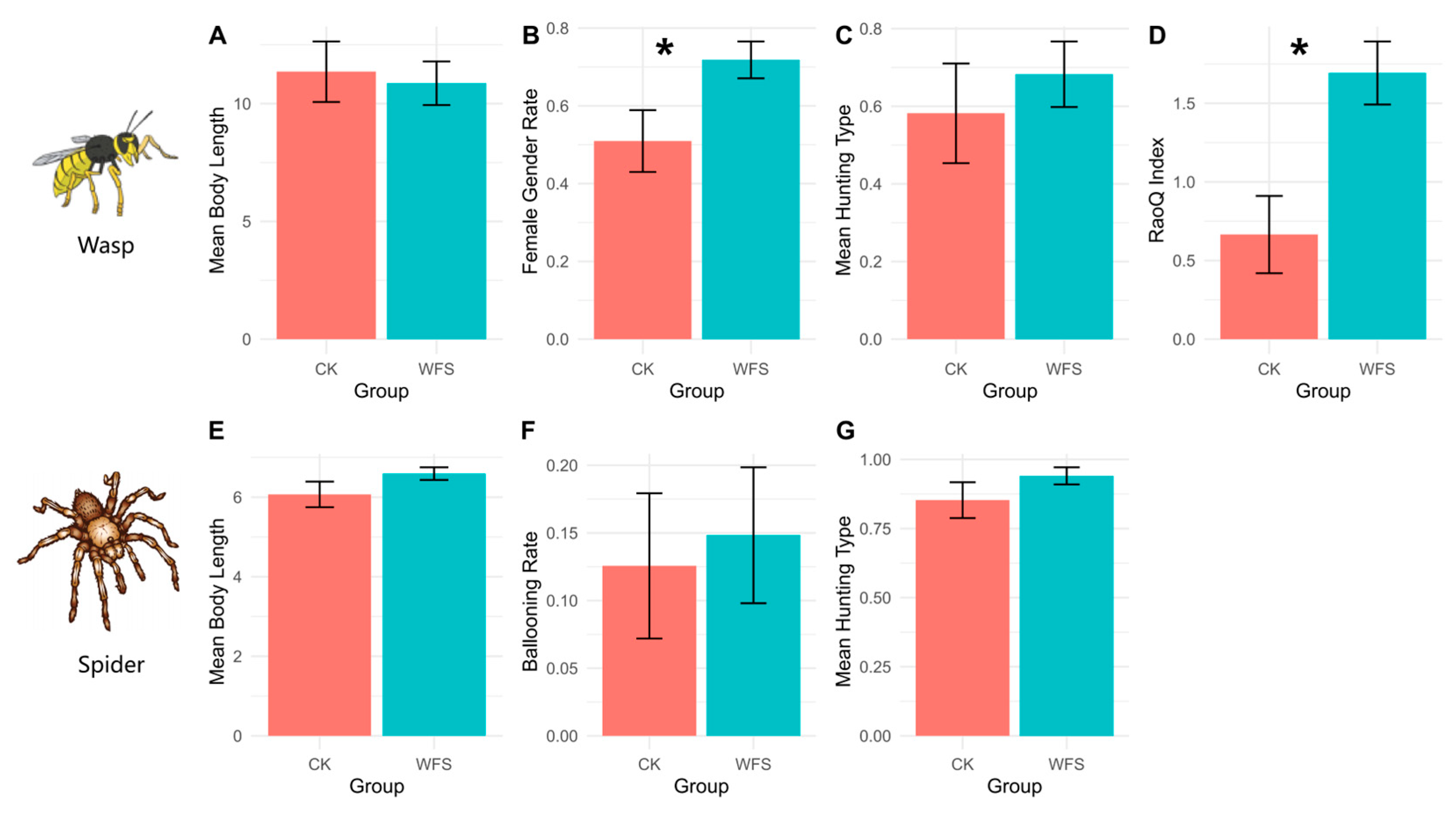

3.2.3. Functional Traits (CWM)

3.3. The Suppression Effect of Natural Enemies on Target Pests in WFS Habitats

3.3.1. Wasps

3.3.2. Spiders

3.4. Responses of Natural Enemies and Target Pests to Wildflower Strip Plant Communities

3.4.1. Wasps

3.4.2. Spiders

3.4.3. Target Pest

4. Discussion

4.1. Wildflower Strips Change Natural Enemy Communities in a Rice-Wheat Agricultural Landscape

4.2. Wildflower Strips Provide Pest Control Services in Agricultural Landscapes

4.3. Wildflower Strip Drive Natural Enemies-Pest Relationship via Changing Plant Community

4.4. Wildflower Strips Could Provide a Path to Balancing Agriculture and Ecology in China

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WFS | Wildflower Strip |

| CK | Control Group |

References

- Van Zanten, B.T.; Verburg, P.H.; Espinosa, M.; Gomez-y-Paloma, S.; Galimberti, G.; Kantelhardt, J.; Kapfer, M.; Lefebvre, M.; Manrique, R.; Piorr, A. European agricultural landscapes, common agricultural policy and ecosystem services: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 34, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Carmona, N.; Sánchez, A.C.; Remans, R.; Jones, S.K. Complex agricultural landscapes host more biodiversity than simple ones: A global meta-analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2091582177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landis, D.A. Designing agricultural landscapes for biodiversity-based ecosystem services. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2017, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekroos, J.; Heliölä, J.; Kuussaari, M. Homogenization of lepidopteran communities in intensively cultivated agricultural landscapes. J. Appl. Ecol. 2010, 47, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács Hostyánszki, A.; Espíndola, A.; Vanbergen, A.J.; Settele, J.; Kremen, C.; Dicks, L.V. Ecological intensification to mitigate impacts of conventional intensive land use on pollinators and pollination. Ecol. Lett. 2017, 20, 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endenburg, S.; Mitchell, G.W.; Kirby, P.; Fahrig, L.; Pasher, J.; Wilson, S. The homogenizing influence of agriculture on forest bird communities at landscape scales. Landsc. Ecol. 2019, 34, 2385–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremen, C.; Chaplin-Kramer, R. Insects as Providers of Ecosystem Services: Crop Pollination and Pest Control; 2007/1/1; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2007; pp. 349–382. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock, B.A.; Isaac, N.J.; Bullock, J.M.; Roy, D.B.; Garthwaite, D.G.; Crowe, A.; Pywell, R.F. Impacts of neonicotinoid use on long-term population changes in wild bees in England. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Librán-Embid, F.; Klaus, F.; Tscharntke, T.; Grass, I. Unmanned aerial vehicles for biodiversity-friendly agricultural landscapes-A systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 732, 139204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duru, M.; Therond, O.; Martin, G.; Martin-Clouaire, R.; Magne, M.; Justes, E.; Journet, E.; Aubertot, J.; Savary, S.; Bergez, J. How to implement biodiversity-based agriculture to enhance ecosystem services: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 1259–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haaland, C.; Naisbit, R.E.; Bersier, L.F. Sown wildflower strips for insect conservation: A review. Insect Conserv. Divers. 2011, 4, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.; Kirmer, A.; Hellwig, N.; Kiehl, K.; Tischew, S. Evaluating CAP wildflower strips: High-quality seed mixtures significantly improve plant diversity and related pollen and nectar resources. J. Appl. Ecol. 2022, 59, 860–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, M.A.; Gurr, G.M.; Wratten, S.D. Beyond nectar provision: The other resource requirements of parasitoid biological control agents. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2016, 159, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staton, T.; Walters, R.J.; Smith, J.; Breeze, T.D.; Girling, R.D. Evaluating a trait-based approach to compare natural enemy and pest communities in agroforestry vs. arable systems. Ecol. Appl. 2021, 31, e2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kratschmer, S.; Pachinger, B.; Schwantzer, M.; Paredes, D.; Guzmán, G.; Goméz, J.A.; Entrenas, J.A.; Guernion, M.; Burel, F.; Nicolai, A. Response of wild bee diversity, abundance, and functional traits to vineyard inter-row management intensity and landscape diversity across Europe. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 4103–4115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkle, L.A.; Belote, R.T.; Myers, J.A. Wildfire severity alters drivers of interaction beta-diversity in plant–bee networks. Ecography 2022, 2022, e5986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaauw, B.R.; Isaacs, R. Wildflower plantings enhance the abundance of natural enemies and their services in adjacent blueberry fields. Biol. Control 2015, 91, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warzecha, D.; Diekötter, T.; Wolters, V.; Jauker, F. Attractiveness of wildflower mixtures for wild bees and hoverflies depends on some key plant species. Insect Conserv. Divers. 2018, 11, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyttenbroeck, R.; Piqueray, J.; Hatt, S.; Mahy, G.; Monty, A. Increasing plant functional diversity is not the key for supporting pollinators in wildflower strips. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 249, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos Fierro, Z.; Garratt, M.P.; Fountain, M.T.; Ashbrook, K.; Westbury, D.B. The potential of wildflower strips to enhance pollination services in sweet cherry orchards grown under polytunnels. J. Appl. Ecol. 2023, 60, 1044–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviron, S.; Berry, T.; Leroy, D.; Savary, G.; Alignier, A. Wild plants in hedgerows and weeds in crop fields are important floral resources for wild flower-visiting insects, independently of the presence of intercrops. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 348, 108410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulli, M.C.; Carmona, D.M.; López, A.N.; Manetti, P.L.; Vincini, A.M.; Cendoya, G. Predación de la babosa Deroceras reticulatum (Pulmonata: Stylommathophora) por Scarites anthracinus (Coleoptera: Carabidae). Ecol. Austral 2009, 19, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Tierranegra-García, N.; Salinas-Soto, P.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; Ocampo-Velázquez, R.V.; Rico-García, E.; Mendoza-Diaz, S.O.; Feregrino-Pérez, A.A.; Mercado-Luna, A.; Vargas-Hernandez, M.; Soto-Zarazúa, G.M. Effect of foliar salicylic acid and methyl jasmonate applications on protection against pill-bugs in lettuce plants (Lactuca sativa). Phytoparasitica 2011, 39, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Mei, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, F.; Duan, M. Recovered grassland area rather than plantation forest could contribute more to protect epigeic spider diversity in northern China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 326, 107726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.; Hu, W.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Li, X.; Wu, P.; Zhang, F.; Shi, H.; Baudry, J. The influence of landscape alterations on changes in ground beetle (Carabidae) and spider (Araneae) functional groups between 1995 and 2013 in an urban fringe of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 689, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tscharntke, T.; Gathmann, A.; Steffan Dewenter, I. Bioindication using trap-nesting bees and wasps and their natural enemies: Community structure and interactions. J. Appl. Ecol. 1998, 35, 708–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, J.T. Biodiversity of hymenoptera. Insect Biodivers. Sci. Soc. 2017, 419–461. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.; Li, F.Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Zhao, D.; Feng, X.; Baoyin, T. Seasonal patterns of the abundance of ground-dwelling arthropod guilds and their responses to livestock grazing in a semi-arid steppe. Pedobiologia 2021, 85, 150711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W.A.; Alfaress, S.; Whitworth, R.J.; McCornack, B.P. Integrated pest management strategies for pillbug (Isopoda: Armadillidiidae) in soybean. Crop Manag. 2013, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Arruda, F.V.; Camarota, F.; Silva, R.R.; Izzo, T.J.; Bergamini, L.L.; Almeida, R.P.S. The potential of arboreal pitfall traps for sampling nontargeted bee and wasp pollinators. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2022, 170, 902–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, V.H.; Osborn, A.L.; Brown, E.R.; Pavlick, C.R.; Enríquez, E.; Tscheulin, T.; Petanidou, T.; Hranitz, J.M.; Barthell, J.F. Effect of pan trap size on the diversity of sampled bees and abundance of bycatch. J. Insect Conserv. 2020, 24, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uetz, G.W.; Unzicker, J.D. Pitfall trapping in ecological studies of wandering spiders. J. Arachnol. 1975, 101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Engelbrecht, I. Pitfall trapping for surveying trapdoor spiders: The importance of timing, conditions and effort. J. Arachnol. 2013, 41, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurlbutt, B. Sexual size dimorphism in parasitoid wasps. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 1987, 30, 63–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Baek, J.H.; Yoon, K.A. Differential properties of venom peptides and proteins in solitary vs. social hunting wasps. Toxins 2016, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, E.C.; Graefe, A.R.; Trauntvein, N.E.; Burns, R.C. Understanding hunting constraints and negotiation strategies: A typology of female hunters. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2015, 20, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penell, A.; Raub, F.; Höfer, H. Estimating biomass from body size of European spiders based on regression models. J. Arachnol. 2018, 46, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyman, G.S.; Sunderland, K.D.; Jepson, P.C. A review of the evolution and mechanisms of ballooning by spiders inhabiting arable farmland. Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 2002, 14, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyffeler, M.; Sterling, W.L.; Dean, D.A. How spiders make a living. Environ. Entomol. 1994, 23, 1357–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.K. T test as a parametric statistic. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2015, 68, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gower, J.C. Principal coordinates analysis. Wiley Statsref Stat. Ref. Online 2014, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.J. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA). Wiley Statsref Stat. Ref. Online 2014, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Muscarella, R.; Uriarte, M. Do community-weighted mean functional traits reflect optimal strategies? Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 283, 20152434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botta Dukát, Z. Rao’s quadratic entropy as a measure of functional diversity based on multiple traits. J. Veg. Sci. 2005, 16, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKight, P.E.; Najab, J. Kruskal-wallis test. In The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, T.J.; Pregibon, D. Generalized Linear Models; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 195–247. [Google Scholar]

- Dormann, C.F.; Elith, J.; Bacher, S.; Buchmann, C.; Carl, G.; Carré, G.; Marquéz, J.R.G.; Gruber, B.; Lafourcade, B.; Leitão, P.J. Collinearity: A review of methods to deal with it and a simulation study evaluating their performance. Ecography 2013, 36, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendel, R.B.; Afifi, A.A. Comparison of stopping rules in forward “stepwise” regression. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1977, 72, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.S.; Murphy, M.A.; Holden, Z.A.; Cushman, S.A. Modeling Species Distribution and Change Using Random Forest; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 139–159. [Google Scholar]

- McKerchar, M.; Potts, S.G.; Fountain, M.T.; Garratt, M.P.; Westbury, D.B. The potential for wildflower interventions to enhance natural enemies and pollinators in commercial apple orchards is limited by other management practices. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 301, 107034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team, R. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, P. VEGAN, a package of R functions for community ecology. J. Veg. Sci. 2003, 14, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.W. labdsv: Ordination and multivariate analysis for ecology. 2016. R. Package Version 2019, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Laliberté, E.; Legendre, P.; Shipley, B.; Laliberté, M.E. Package ‘fd’. Meas. Funct. Divers. Mult. Trait. Other Tools Funct. Ecol. 2014, 1, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, J.; Friendly, G.G.; Graves, S.; Heiberger, R.; Monette, G.; Nilsson, H.; Ripley, B.; Weisberg, S.; Fox, M.J.; Suggests, M. The car package. R Found. Stat. Comput. 2007, 1109, 1431. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, J.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Peres Neto, P.R. Generalizing hierarchical and variation partitioning in multiple regression and canonical analyses using the rdacca. hp R package. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2022, 13, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschumi, M.; Albrecht, M.; Collatz, J.; Dubsky, V.; Entling, M.H.; Najar Rodriguez, A.J.; Jacot, K. Tailored flower strips promote natural enemy biodiversity and pest control in potato crops. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 53, 1169–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, T.; Reiff, J.M.; Theiss, K.; Entling, M.H.; Hoffmann, C. Reduced fungicide applications improve insect pest control in grapevine. Biocontrol 2018, 63, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Z.; de Groot, G.A.; Kleijn, D.; Dimmers, W.; van Gils, S.; Lammertsma, D.; van Kats, R.; Scheper, J. Flower availability drives effects of wildflower strips on ground-dwelling natural enemies and crop yield. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 319, 107570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollier, A.; Tricault, Y.; Plantegenest, M.; Bischoff, A. Sowing of margin strips rich in floral resources improves herbivore control in adjacent crop fields. Agr. For. Entomol. 2019, 21, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mockford, A.; Urbaneja, A.; Ashbrook, K.; Westbury, D.B. Developing perennial wildflower strips for use in Mediterranean orchard systems. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 13, e10285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateos-Fierro, Z.; Fountain, M.T.; Garratt, M.P.; Ashbrook, K.; Westbury, D.B. Active management of wildflower strips in commercial sweet cherry orchards enhances natural enemies and pest regulation services. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 317, 107485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, E.C.; Dobbert, S.; Pape, R.; Löffler, J. Patterns, timing, and environmental drivers of growth in two coexisting green-stemmed Mediterranean alpine shrubs species. New Phytol. 2024, 241, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, U.S.; Jauker, F.; Lanzen, J.; Warzecha, D.; Wolters, V.; Diekötter, T. Prey-dependent benefits of sown wildflower strips on solitary wasps in agroecosystems. Insect Conserv. Divers. 2018, 11, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toivonen, M.; Huusela-Veistola, E.; Herzon, I. Perennial fallow strips support biological pest control in spring cereal in Northern Europe. Biol. Control 2018, 121, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, J.; Antkowiak, M.; Sienkiewicz, P. Flower strips and their ecological multifunctionality in agricultural fields. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grab, H.; Branstetter, M.G.; Amon, N.; Urban-Mead, K.R.; Park, M.G.; Gibbs, J.; Blitzer, E.J.; Poveda, K.; Loeb, G.; Danforth, B.N. Agriculturally dominated landscapes reduce bee phylogenetic diversity and pollination services. Science 2019, 363, 282–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balzan, M.V.; Bocci, G.; Moonen, A. Augmenting flower trait diversity in wildflower strips to optimise the conservation of arthropod functional groups for multiple agroecosystem services. J. Insect Conserv. 2014, 18, 713–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, M.; Kleijn, D.; Williams, N.M.; Tschumi, M.; Blaauw, B.R.; Bommarco, R.; Campbell, A.J.; Dainese, M.; Drummond, F.A.; Entling, M.H. The effectiveness of flower strips and hedgerows on pest control, pollination services and crop yield: A quantitative synthesis. Ecol. Lett. 2020, 23, 1488–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serée, L.; Chiron, F.; Valantin-Morison, M.; Barbottin, A.; Gardarin, A. Flower strips, crop management and landscape composition effects on two aphid species and their natural enemies in faba bean. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 331, 107902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassou, A.G.; Tixier, P. Response of pest control by generalist predators to local-scale plant diversity: A meta-analysis. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 6, 1143–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartual, A.M.; Sutter, L.; Bocci, G.; Moonen, A.; Cresswell, J.; Entling, M.; Giffard, B.; Jacot, K.; Jeanneret, P.; Holland, J. The potential of different semi-natural habitats to sustain pollinators and natural enemies in European agricultural landscapes. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2019, 279, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.S.; Olds, A.D.; Olalde, A.B.; Berkström, C.; Gilby, B.L.; Schlacher, T.A.; Butler, I.R.; Yabsley, N.A.; Zann, M.; Connolly, R.M. Habitat proximity exerts opposing effects on key ecological functions. Landsc. Ecol. 2018, 33, 1273–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triquet, C.; Roume, A.; Tolon, V.; Wezel, A.; Ferrer, A. Undestroyed winter cover crop strip in maize fields supports ground-dwelling arthropods and predation. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 326, 107783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalko, R.; Pekár, S.; Entling, M.H. An updated perspective on spiders as generalist predators in biological control. Oecologia 2019, 189, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Li, Z.; Ouyang, F.; Men, X.; Zhang, K.; Liu, M.; Guo, W.; Zhu, C.; Zhao, W.; Reddy, G.V. Flower strips promote natural enemies, provide efficient aphid biocontrol, and reduce insecticide requirement in cotton crops. Entomol. Gen. 2022, 43, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Orta, G.; Madeira, F.; Batuecas, I.; Sossai, S.; Juárez-Escario, A.; Albajes, R. Changes in landscape composition influence the abundance of insects on maize: The role of fruit orchards and alfalfa crops. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 291, 106805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarthou, J.; Badoz, A.; Vaissière, B.; Chevallier, A.; Rusch, A. Local more than landscape parameters structure natural enemy communities during their overwintering in semi-natural habitats. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 194, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, D.; Lami, F.; Pantini, P.; Marini, L. Using species-habitat networks to inform agricultural landscape management for spiders. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 239, 108275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boetzl, F.A.; Krimmer, E.; Holzschuh, A.; Krauss, J.; Steffan-Dewenter, I. Arthropod overwintering in agri-environmental scheme flowering fields differs among pollinators and natural enemies. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 330, 107890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Tian, Y.; Sun, K. Dynamic analysis of additional food provided non-smooth pest-natural enemy models based on nonlinear threshold control. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 2025, 71, 2645–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junge, X.; Jacot, K.A.; Bosshard, A.; Lindemann-Matthies, P. Swiss people’s attitudes towards field margins for biodiversity conservation. J. Nat. Conserv. 2009, 17, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, M.E.; Woodcock, B.A.; Lobley, M.; Pywell, R.F.; Saratsi, E.; Swetnam, R.D.; Mortimer, S.R.; Harris, S.J.; Winter, M.; Hinsley, S. Social and ecological drivers of success in agri-environment schemes: The roles of farmers and environmental context. J. Appl. Ecol. 2015, 52, 696–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks, L.V.; Baude, M.; Roberts, S.P.; Phillips, J.; Green, M.; Carvell, C. How much flower-rich habitat is enough for wild pollinators? Answering a key policy question with incomplete knowledge. Ecol. Entomol. 2015, 40, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delphia, C.M.; O Neill, K.M.; Burkle, L.A. Wildflower seed sales as incentive for adopting flower strips for native bee conservation: A cost-benefit analysis. J. Econ. Entomol. 2019, 112, 2534–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, H.E.; Adams, C.R.; Kane, M.E.; Norcini, J.G.; Acomb, G.; Larsen, C. Awareness of and interest in native wildflowers among college students in plant-related disciplines: A case study from Florida. Horttechnology 2010, 20, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretzel, F.; Pezzarossa, B.; Carrai, C.; Malorgio, F. Wildflower plantings to reduce the management costs of urban gardens and roadsides. In Proceedings of the VI International Symposium on New Floricultural Crops, Viña del Mar, Chile, 2 November 2009; pp. 263–270. [Google Scholar]

- Bretzel, F.; Vannucchi, F.; Romano, D.; Malorgio, F.; Benvenuti, S.; Pezzarossa, B. Wildflowers: From conserving biodiversity to urban greening—A review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 20, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, T.; Albani, M.; Wilkinson, M.; Coupland, G.; Battey, N. The Diversity and Significance of Flowering in Perennials. In Annual Plant Reviews Volume 20: Flowering and Its Manipulation; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 181–197. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, N.M.; Ward, K.L.; Pope, N.; Isaacs, R.; Wilson, J.; May, E.A.; Ellis, J.; Daniels, J.; Pence, A.; Ullmann, K. Native wildflower plantings support wild bee abundance and diversity in agricultural landscapes across the United States. Ecol. Appl. 2015, 25, 2119–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Functional Trait | Description | Data Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wasps | Body Length | Average body length of wasps, randomly sampled from three individuals per species and averaged [34] | mm |

| Hunting Type | Ratio of predatory individuals to parasitic individuals [35] | Parasitic = 1; Predatory = 0 | |

| Gender | Ratio of female to male individuals, calculated independently for different species [36] | Number of females/Number of males | |

| Spiders | Body Length | Average body length of spiders, randomly sampled from three individuals per species and averaged [37] | mm |

| Ballooning Ability | Proportion of individuals with ballooning capability among the total population [38] | Ballooning species = 1; Other species = 0 | |

| Hunting Type | Ratio of hunter individuals to web weaver individuals [39] | Hunters = 1; Web weavers = 0 |

| Diversity Index | t | df | p | Mean in CK Group | Mean in WFS Group | 95% CI | WFS/CK | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wasps | ||||||||

| Species richness 1 | −2.827 | 21.91 | 0.01 | 1.833 | 3.583 | [−3.034, −0.466] | 195.47% | ** |

| Activity Density 1 | −4.403 | 16.415 | <0.001 | 2.417 | 8.75 | [−9.377, −3.29] | 362.02% | *** |

| Shannon-Wiener Diversity | −2.613 | 20.429 | 0.016 | 0.438 | 0.998 | [−1.006, −0.113] | 227.85% | * |

| Simpson Diversity | −1.635 | 16.009 | 0.122 | 0.339 | 0.539 | [−0.459, 0.059] | 159.00% | |

| Spiders | ||||||||

| Species richness 1 | 0.428 | 17.0 | 0.674 | 1.59 | 1.51 | [−0.340, 0.513] | 94.97% | |

| Activity Density 1 | 0.231 | 19.8 | 0.820 | 2.14 | 2.05 | [−0.725, 0.905] | 95.79% | |

| Shannon-Wiener Diversity | 0.857 | 16.4 | 0.404 | 1.21 | 1.02 | [−0.287, 0.679] | 84.30% | |

| Simpson Diversity | 1.42 | 13.5 | 0.178 | 0.655 | 0.514 | [−0.073, 0.355] | 78.47% | |

| Target Pest control Service | ||||||||

| Pest Activity Density | 2.5995 | 13.718 | 0.021 | 525.25 | 168.25 | [61.88, 652.12] | 32.03% | * |

| Groups | Term | Estimate | Std. Error | Z | p | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wasps | Intercept | 4.492 | 0.632 | 6.775 | <0.001 | *** |

| Gender (Female Rate) | −3.277 | 1.3499 | 2.135 | 0.0327 | * | |

| Spiders | Intercept | 2.3031 | 2.8006 | 0.791 | 0.4289 | |

| Hunting Type (Predatory individuals Rate) | 5.0522 | 1.984 | 2.228 | 0.0259 | * | |

| PCoA1 | 1.724 | 0.7966 | 1.891 | 0.0586 |

| Diversity | Plant Explanatory Variables | Estimate | Std. Error | Z | p | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species Richness | Community Composition (PCoA1) | −0.783 | 0.441 | −1.777 | 0.076 | |

| Activity Density | Species Richness | 0.255 | 0.144 | 1.779 | 0.075 | |

| Total Coverage | −0.195 | 0.112 | −1.744 | 0.081 | ||

| Shannon Diversity | Simpson Diversity | −4.049 | 2.507 | −1.615 | 0.141 | |

| Community Composition (PCoA1) | −1.282 | 0.362 | −3.542 | 0.006 | ** | |

| Simpson Diversity | Simpson | −1.910 | 1.071 | −1.784 | 0.108 | |

| Community Composition (PCoA1) | −0.534 | 0.155 | −3.451 | 0.007 | ** | |

| Mean Body Length | Total Coverage | −1.364 | 0.771 | −1.769 | 0.120 | |

| Simpson Diversity | 84.482 | 54.181 | 1.559 | 0.163 | ||

| Community Composition (PCoA1) | 7.049 | 4.881 | 1.444 | 0.192 | ||

| Community Composition (PCoA2) | −15.865 | 7.614 | −2.084 | 0.076 |

| Diversity | Plant Explanatory Variables | Estimate | Std. Error | Z | p | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species Richness | Total Coverage | −0.358 | 0.130 | −2.745 | 0.006 | ** |

| Simpson Diversity | 18.667 | 9.178 | 2.034 | 0.042 | * | |

| Community Composition (PCoA2) | −3.050 | 1.280 | −2.382 | 0.017 | * | |

| Floral Resources | 0.010 | 0.005 | 2.032 | 0.042 | * | |

| Activity Density | Species Richness | −1.212 | 0.373 | −3.250 | 0.001 | ** |

| Simpson Diversity | 21.180 | 9.405 | 2.252 | 0.024 | * | |

| Community Composition (PCoA1) | −1.323 | 0.668 | −1.980 | 0.048 | * | |

| Shannon Diversity | Total Coverage | −0.298 | 0.131 | −2.266 | 0.058 | |

| Simpson Diversity | 15.967 | 10.247 | 1.558 | 0.163 | ||

| Community Composition (PCoA2) | −2.891 | 1.319 | −2.192 | 0.065 | ||

| Floral Resources | 0.009 | 0.006 | 1.545 | 0.166 | ||

| Simpson Diversity | Total Coverage | −0.117 | 0.069 | −1.687 | 0.136 | |

| Simpson Diversity | 6.848 | 5.419 | 1.264 | 0.247 | ||

| Community Composition (PCoA2) | −1.332 | 0.698 | −1.909 | 0.098 | ||

| Floral Resources | 0.004 | 0.003 | 1.195 | 0.271 | ||

| Mean Body Length | Simpson Diversity | −6.004 | 4.074 | −1.474 | 0.179 | |

| Community Composition (PCoA2) | −2.343 | 1.237 | −1.895 | 0.095 | ||

| Floral Resources | 0.013 | 0.009 | 1.564 | 0.156 |

| Diversity | Plant Explanatory Variables | Estimate | Std. Error | Z | p | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target Pest Density | Species Richness | −0.325 | 0.180 | −1.804 | 0.071 | |

| Floral Resources | −0.018 | 0.005 | −3.688 | 0.000 | *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, W.; Ni, K.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, S.; Shao, X.; Yu, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, R.; Duan, M.; Xu, W. Plant-Driven Effects of Wildflower Strips on Natural Enemy Biodiversity and Pest Suppression in an Agricultural Landscape in Hangzhou, China. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1286. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15061286

Hu W, Ni K, Zhu Y, Liu S, Shao X, Yu Z, Wang L, Zhang R, Duan M, Xu W. Plant-Driven Effects of Wildflower Strips on Natural Enemy Biodiversity and Pest Suppression in an Agricultural Landscape in Hangzhou, China. Agronomy. 2025; 15(6):1286. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15061286

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Wenhao, Kang Ni, Yu Zhu, Shuyi Liu, Xuhua Shao, Zhenrong Yu, Luyu Wang, Rui Zhang, Meichun Duan, and Wenhui Xu. 2025. "Plant-Driven Effects of Wildflower Strips on Natural Enemy Biodiversity and Pest Suppression in an Agricultural Landscape in Hangzhou, China" Agronomy 15, no. 6: 1286. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15061286

APA StyleHu, W., Ni, K., Zhu, Y., Liu, S., Shao, X., Yu, Z., Wang, L., Zhang, R., Duan, M., & Xu, W. (2025). Plant-Driven Effects of Wildflower Strips on Natural Enemy Biodiversity and Pest Suppression in an Agricultural Landscape in Hangzhou, China. Agronomy, 15(6), 1286. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15061286