Effects of Tillage Practices on Soil Quality and Maize Yield in the Semi-Humid Region of Northeast China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

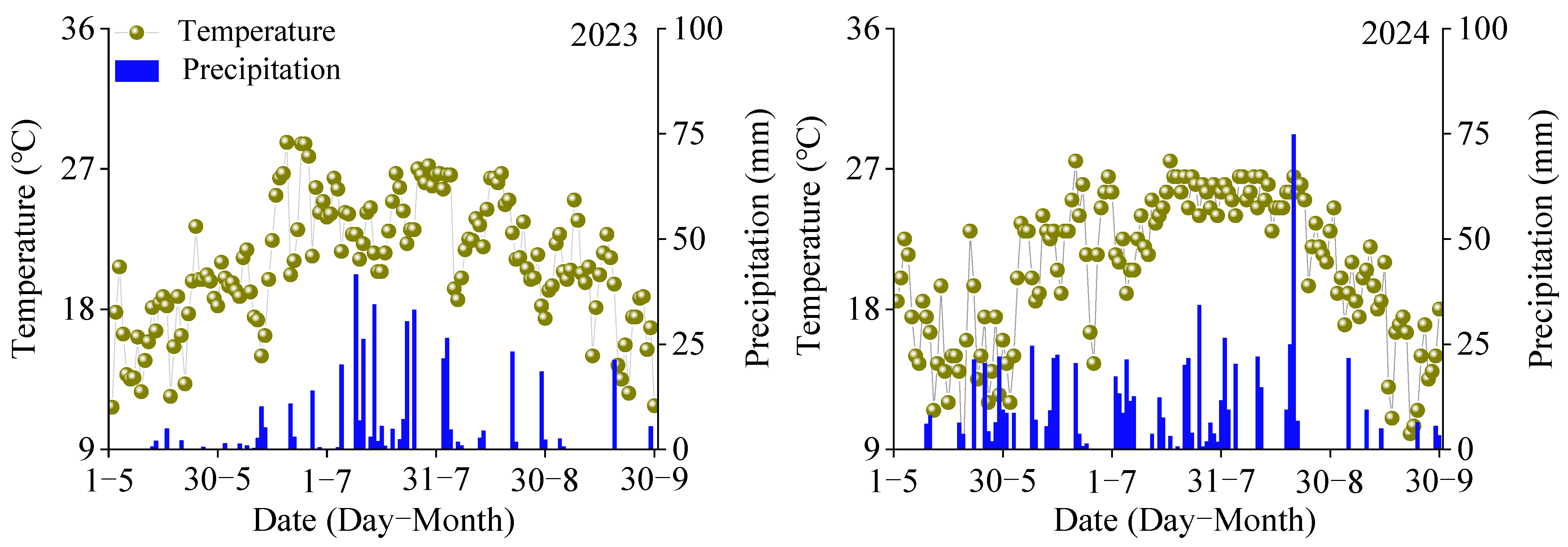

2.1. Study Site and Experimental Description

2.2. Plant Sampling and Testing

2.3. Soil Sampling and Analysis

2.4. Soil Quality Index Calculation

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

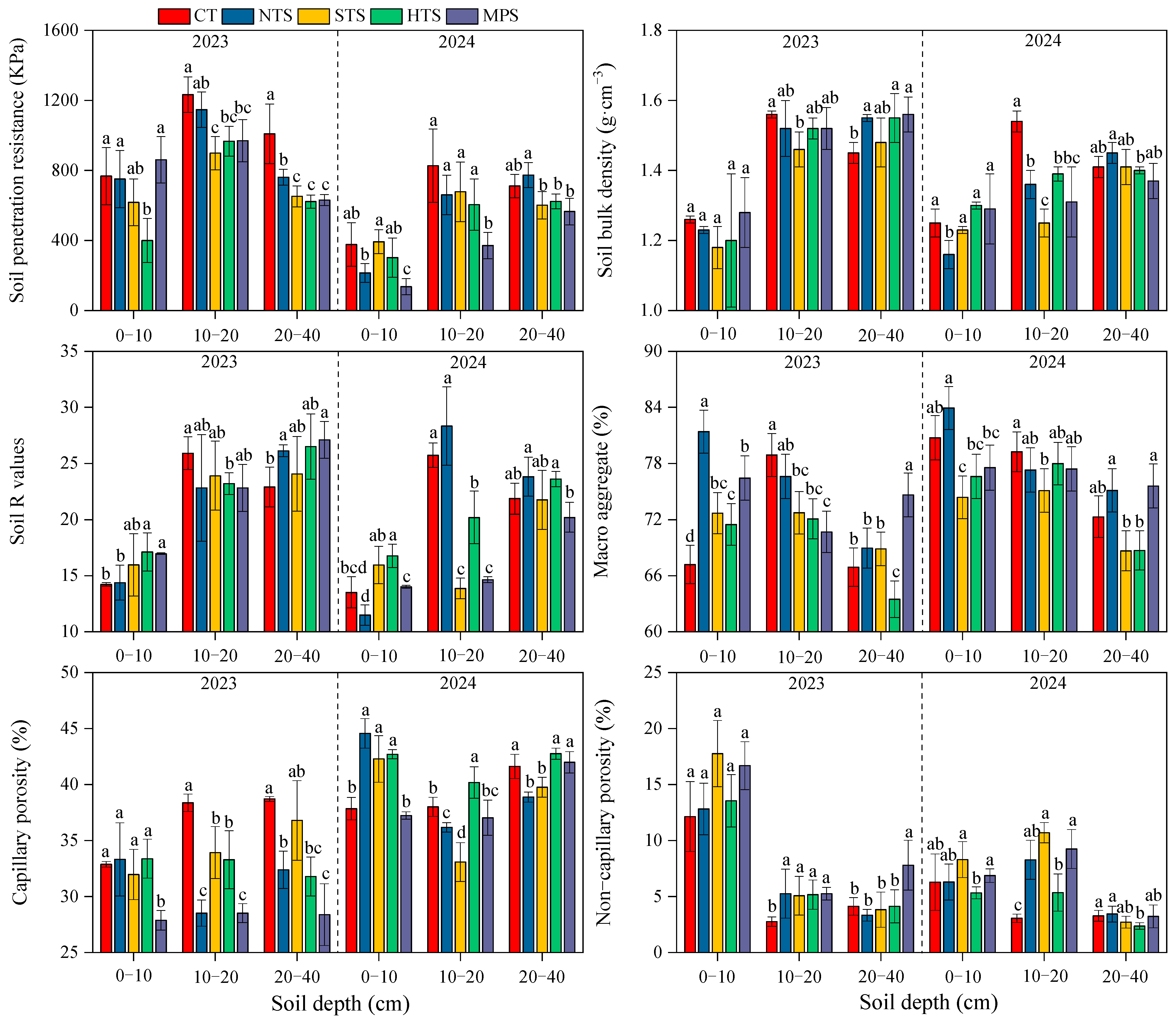

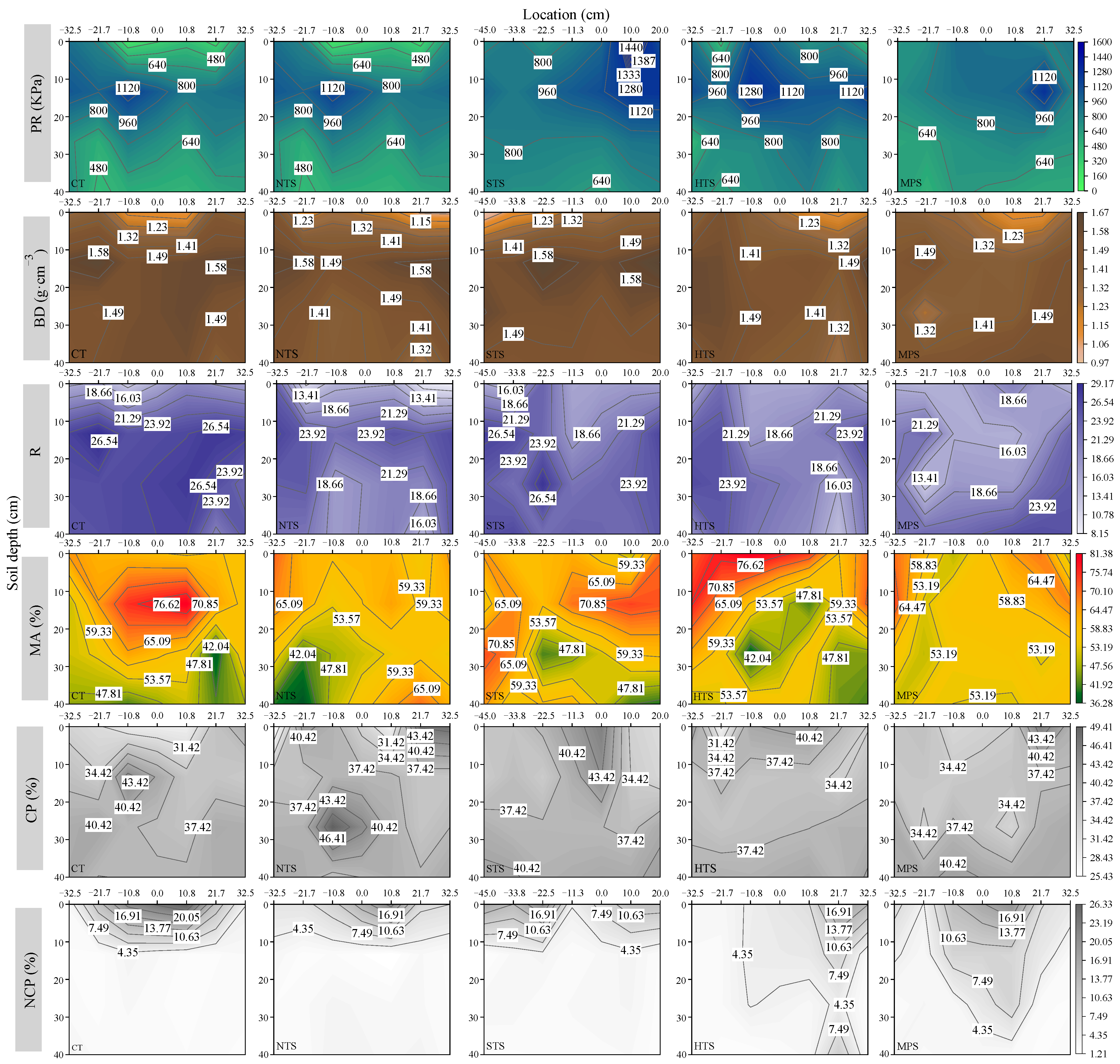

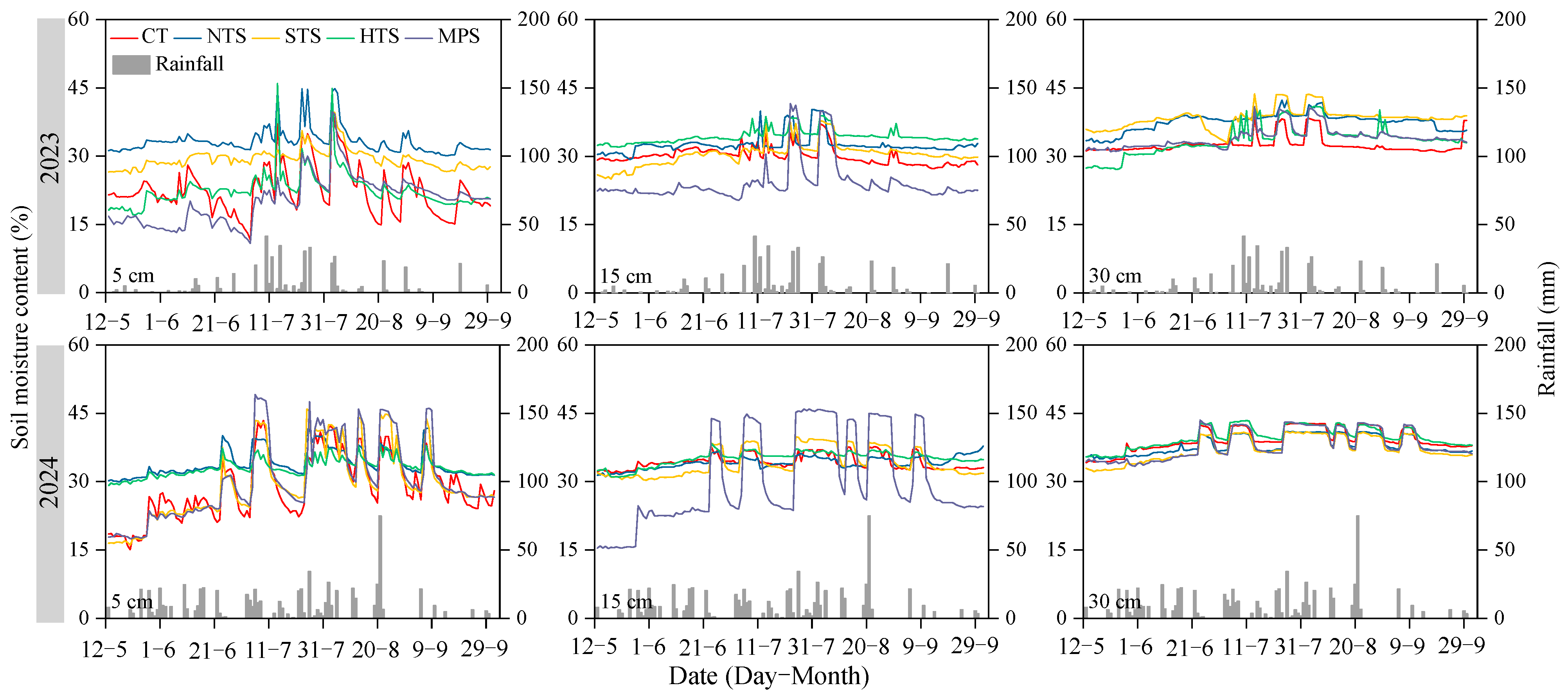

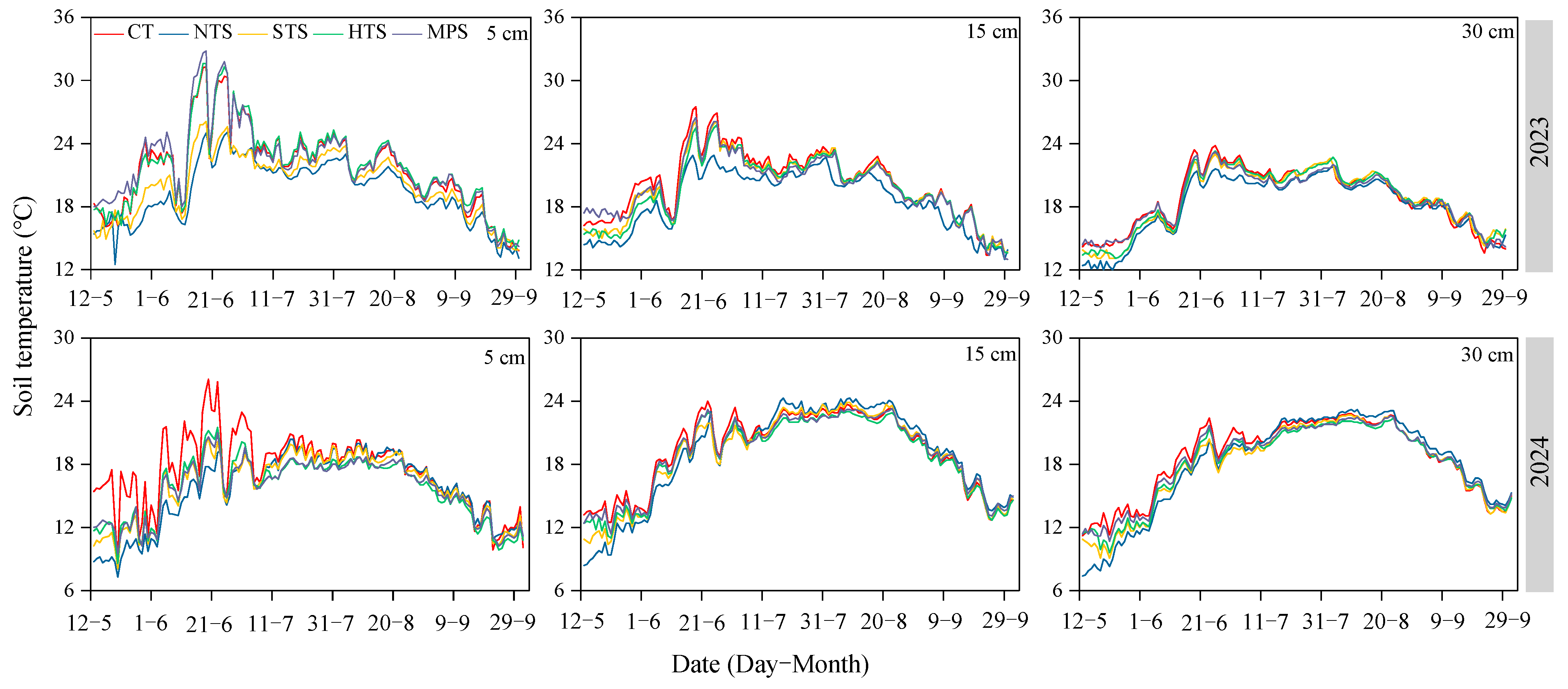

3.1. The Impact of Different Tillage Practices on Soil Structure and Hydrothermal Properties

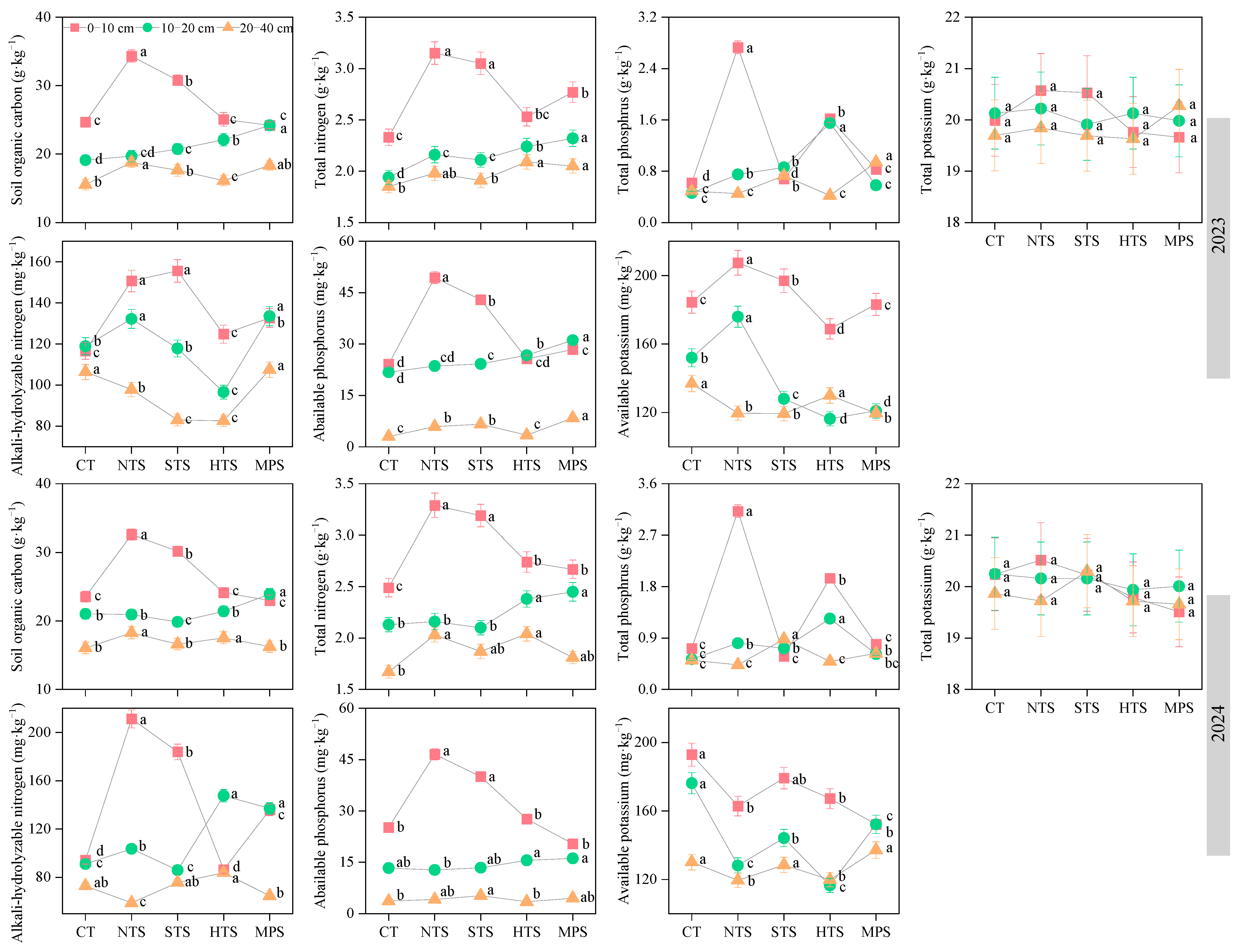

3.2. The Impact of Different Tillage Practices on Soil Organic Matter and Nutrient Content

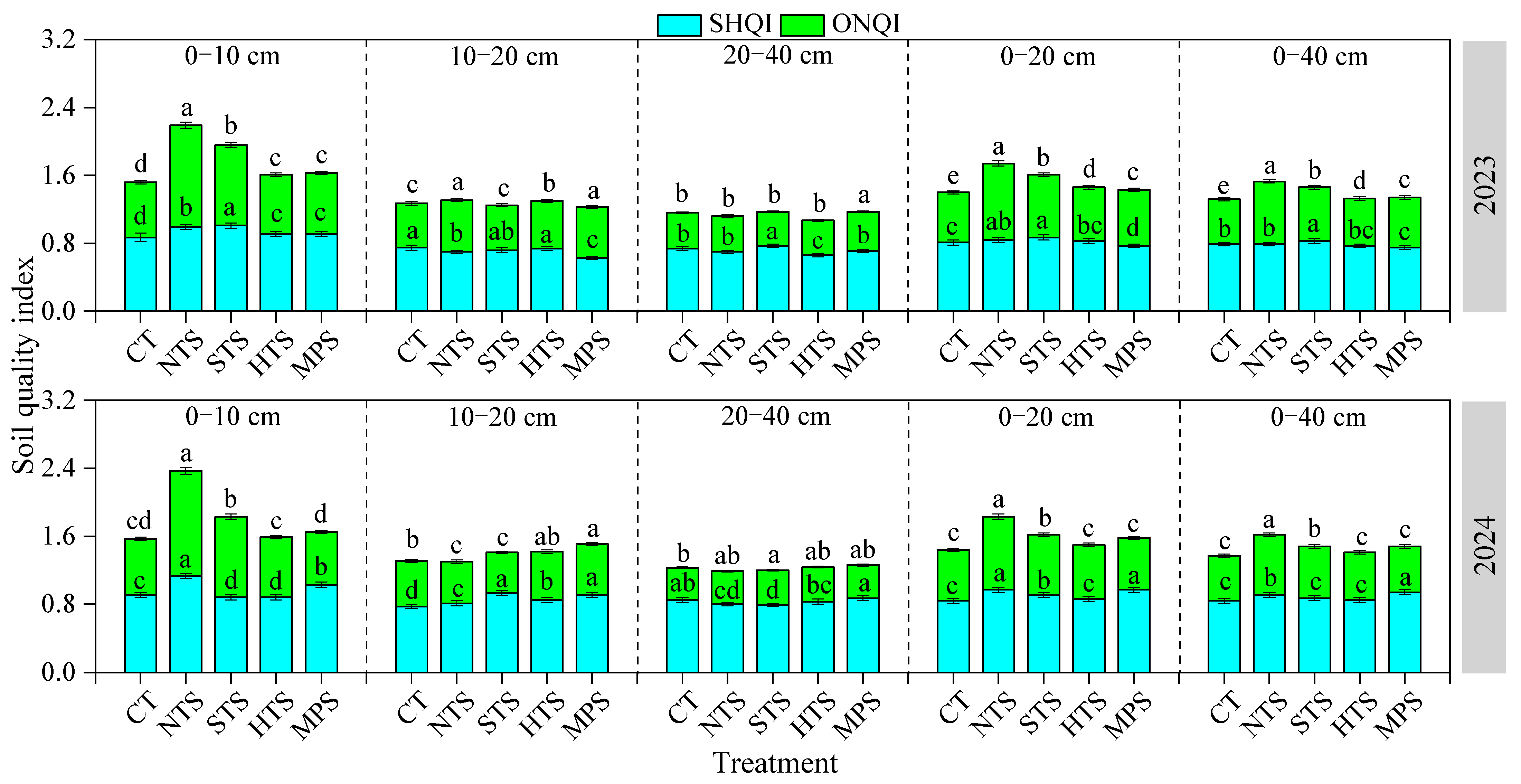

3.3. The Impact of Different Tillage Practices on Soil Quality Index

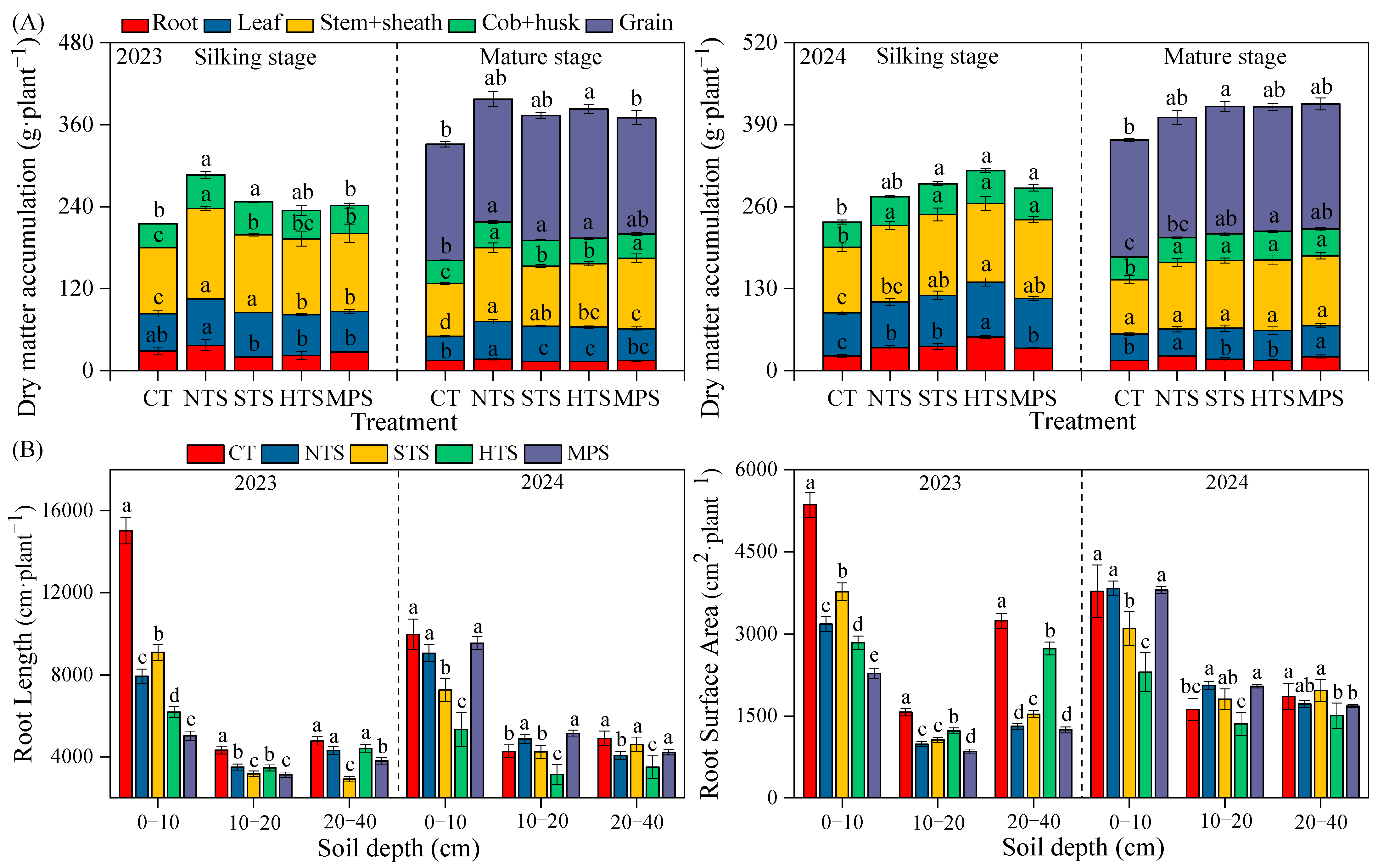

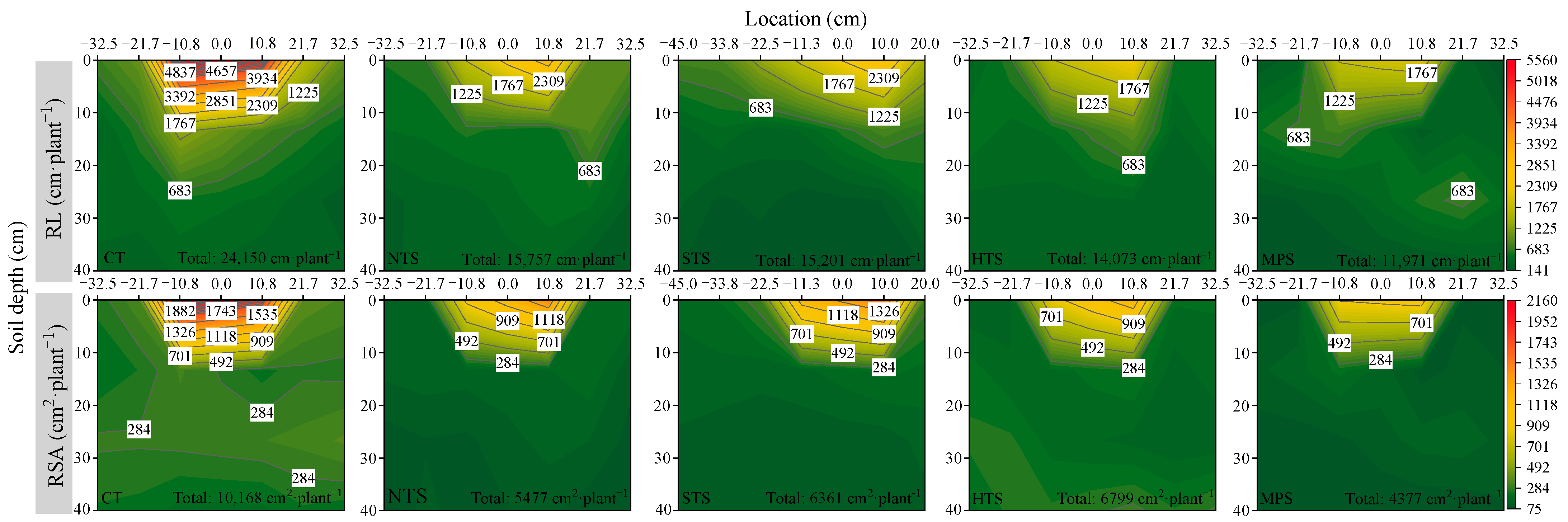

3.4. The Impact of Different Tillage Practices on Dry Matter Accumulation and Root Distribution in Maize

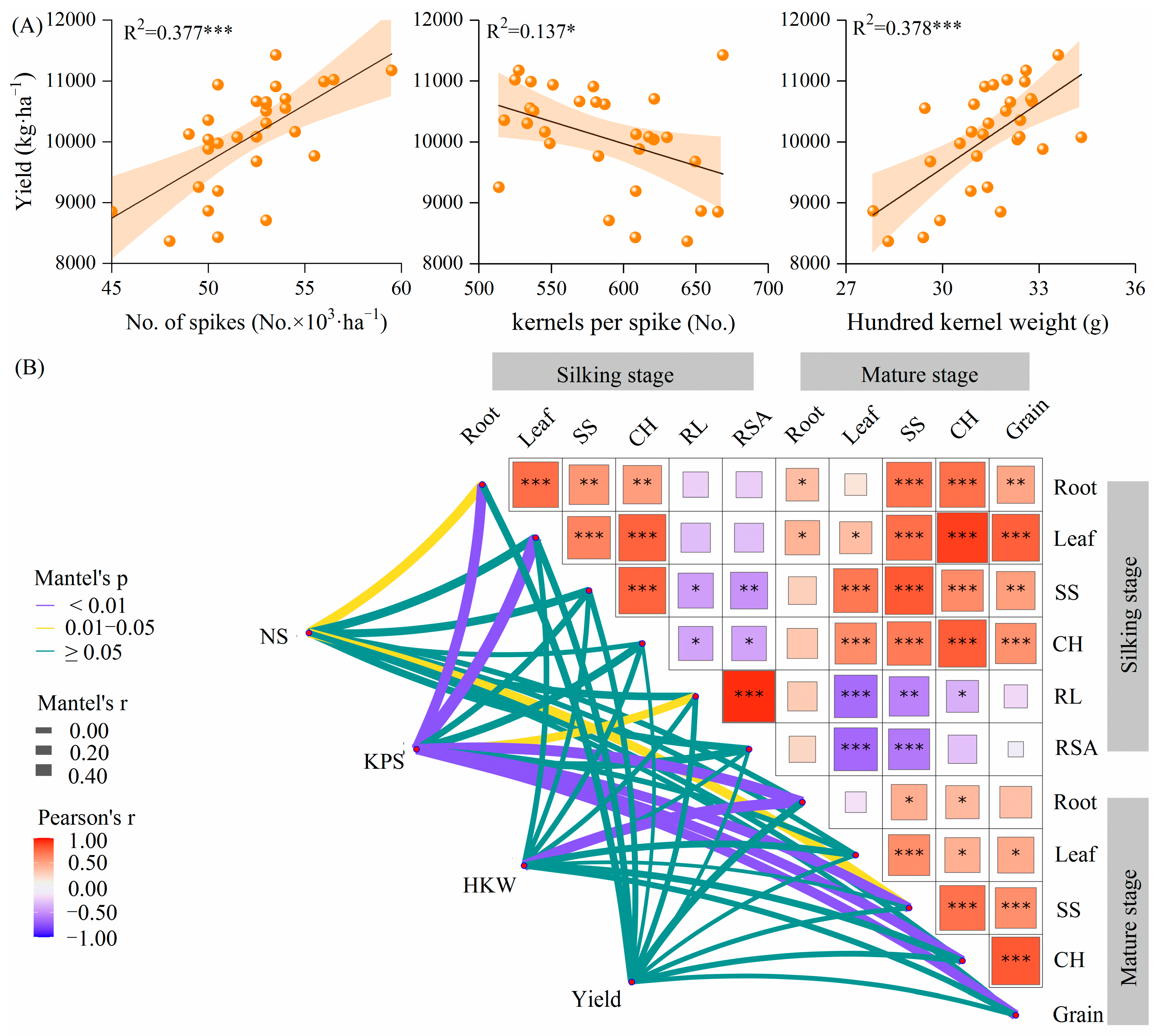

3.5. The Impact of Different Tillage Practices on Maize Yield and Its Components

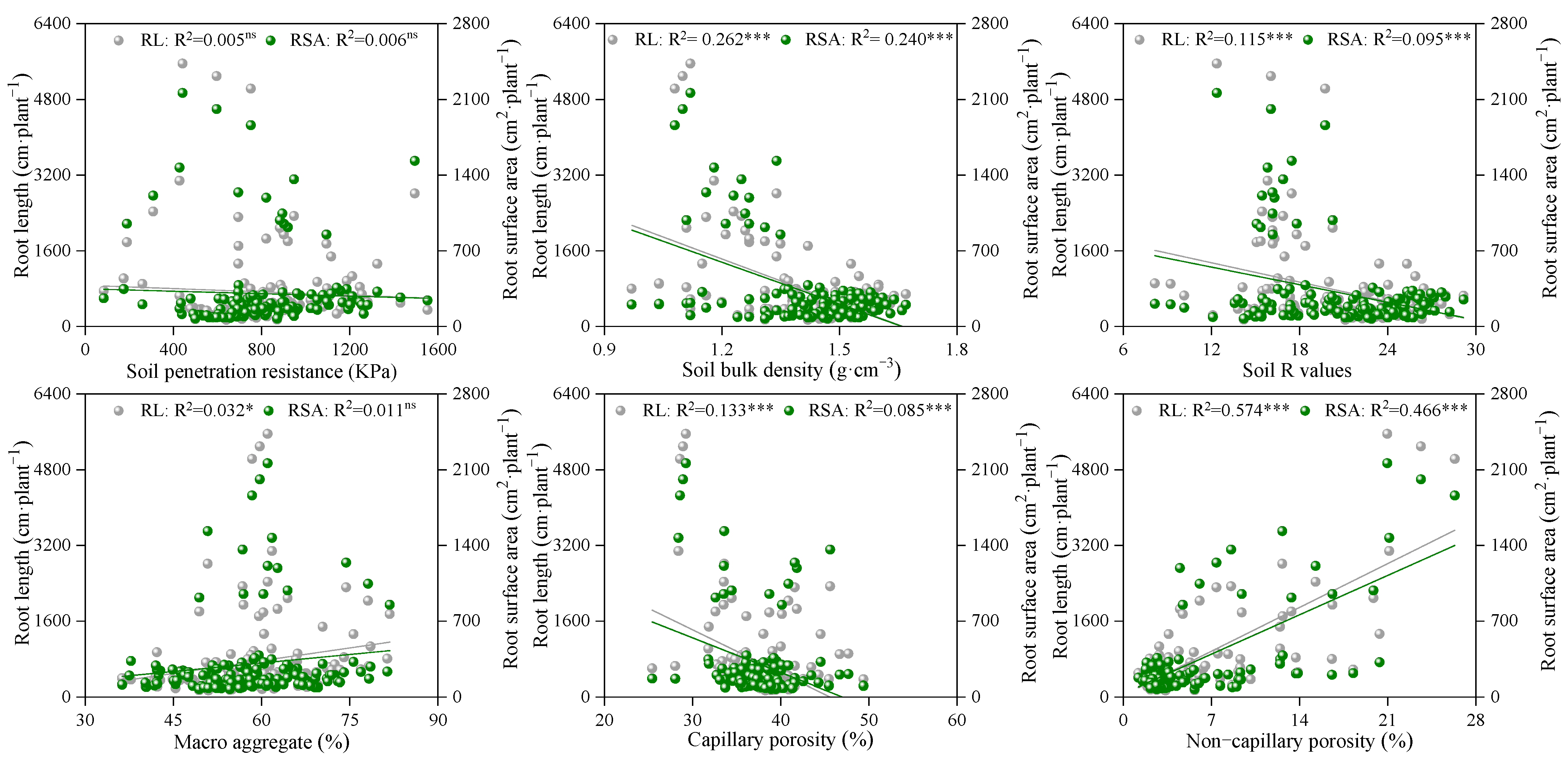

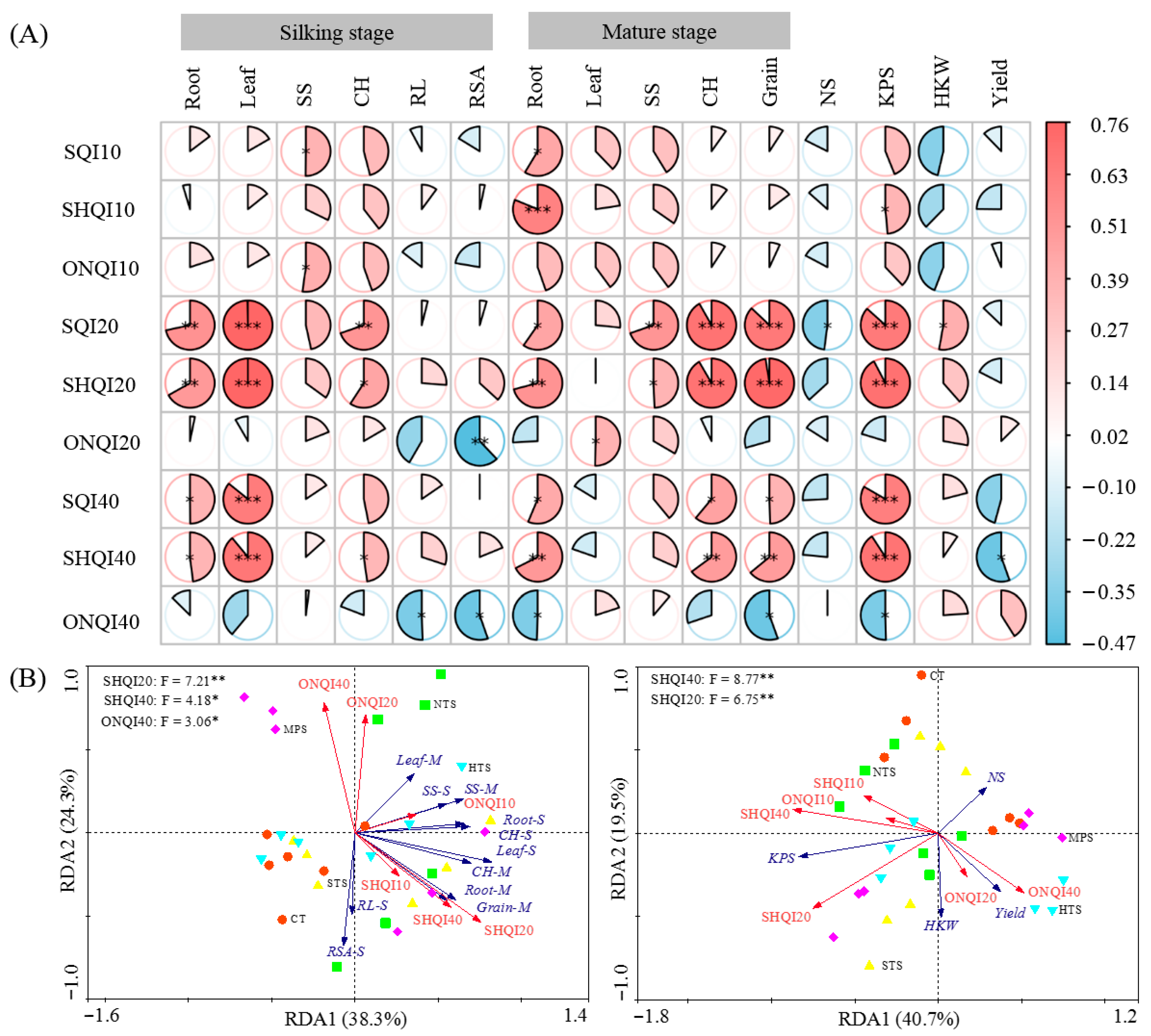

3.6. The Correlation Between Grain Yield, Plant Indicators, and Soil Quality

4. Discussion

4.1. The Impact of Different Tillage Practices on Soil Quality

4.2. The Impact of Different Tillage Practices on the Distribution of Maize Roots

4.3. The Impact of Different Tillage Practices on Dry Matter Accumulation and Yield of Maize

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hu, Y.; Li, X.; Guo, S.; Gao, X.; Ou, X.; Liu, B. On-Site Soil Dislocation and Localized CNP Degradation: The Real Erosion Risk Faced by Sloped Cropland in Northeastern China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 302, 107088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Liu, E.; Tian, Q.; Yan, C.; Zhang, Y. Soil Nitrogen Dynamics and Crop Residues. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 34, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surekha, K.; App, K.; Reddy, M.N.; Satyanarayana, K.; Sta Cruz, P.C. Crop Residue Management to Sustain Soil Fertility and Irrigated Rice Yields. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2003, 67, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, J.W.; Zeiss, M.R. Soil Health and Sustainability: Managing the Biotic Component of Soil Quality. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2000, 15, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villamil, M.B.; Little, J.; Nafziger, E.D. Corn Residue, Tillage, and Nitrogen Rate Effects on Soil Properties. Soil Tillage Res. 2015, 151, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.; Sleutel, S.; Buchan, D.; De Neve, S.; Cai, D.; Gabriëls, D.; Jin, J. Changes of Soil Enzyme Activities Under Different Tillage Practices in the Chinese Loess Plateau. Soil Tillage Res. 2009, 104, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Zhao, B.; Zhu, L.S.; Xu, J.; Zhang, F. Effects of Long-Term Fertilization on Soil Enzyme Activities and Its Role in Adjusting-Controlling Soil Fertility. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2003, 9, 406–410. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Si, B.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Z.; Lu, X.; Chen, X.; Han, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zou, W. Drivers of Soil Quality and Maize Yield Under Long-Term Tillage and Straw Incorporation in Mollisols. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 246, 106360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, V.; Verhulst, N.; Cox, R.; Govaerts, B. Weed Dynamics and Conservation Agriculture Principles: A Review. Field Crops Res. 2015, 183, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.X.; Chen, X.W.; Jia, S.X.; Liang, A.Z.; Zhang, X.P.; Yang, X.M.; Wei, S.C.; Sun, B.J.; Huang, D.D.; Zhou, G.Y. The Potential Mechanism of Long-Term Conservation Tillage Effects on Maize Yield in the Black Soil of Northeast China. Soil Tillage Res. 2015, 154, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keesstra, S.D.; Rodrigo-Comino, J.; Novara, A.; Giménez-Morera, A.; Pulido, M.; Di Prima, S.; Cerdà, A. Straw Mulch as a Sustainable Solution to Decrease Runoff and Erosion in Glyphosate-Treated Clementine Plantations in Eastern Spain. An Assessment Using Rainfall Simulation Experiments. Catena 2019, 174, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, M.; Horn, R.; Ren, T. Soil Water Retention Dynamics in a Mollisol During a Maize Growing Season Under Contrasting Tillage Systems. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 209, 104953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Liu, Y.; Chen, T.; Zheng, Z.; Peng, G.; Zou, Y.; Tang, C.; Shan, X.; Zhou, Q.; Li, J. Responses of Soil Aggregates, Organic Carbon, and Crop Yield to Short-Term Intermittent Deep Tillage in Southern China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 298, 126767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, L.; Wang, Z.; Song, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Jia, X. Tillage Practices Affect the Grain Filling of Inferior Kernel of Summer Maize by Regulating Soil Water Content and Photosynthetic Capacity. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 245, 106600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raper, R.L.; Bergtold, J. In-Row Subsoiling: A Review and Suggestions for Reducing Cost of This Conservation Tillage Operation. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2007, 23, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.N.; Tanveer, M.; Shahzad, B.; Yang, G.; Fahad, S.; Ali, S.; Bukhari, M.A.; Tung, S.A.; Hafeez, A.; Souliyanonh, B. Soil Compaction Effects on Soil Health and Crop Productivity: An Overview. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 10056–10067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zheng, J.; Xie, R.; Ming, B.; Peng, X.; Luo, Y.; Zheng, H.; Sui, P.; Wang, K.; Hou, P.; et al. Potential Mechanisms of Maize Yield Reduction Under Short-Term No-Tillage Combined With Residue Coverage in the Semi-Humid Region of Northeast China. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 217, 105289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Hafeez, M.B.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, Q.; Wang, R.; Wang, X.; Li, J. No-Tillage and Subsoiling Increased Maize Yields and Soil Water Storage Under Varied Rainfall Distribution: A 9-Year Site-Specific Study in a Semi-Arid Environment. Field Crops Res. 2020, 255, 107867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Chen, X.; Han, X.; Lu, X.; Yan, J.; Zou, W.; Yan, L. Responses of Microbial Nutrient Acquisition to Depth of Tillage and Incorporation of Straw in a Chinese Mollisol. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 737075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, X.; Sun, L.; Ren, J.; Yuan, Y.; Zang, S. Influence of Tillage on the Mollisols Physicochemical Properties, Seed Emergence and Yield of Maize in Northeast China. Agriculture 2021, 11, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tormena, C.A.; Karlen, D.L.; Logsdon, S.; Cherubin, M.R. Corn Stover Harvest and Tillage Impacts on Near-Surface Soil Physical Quality. Soil Tillage Res. 2017, 166, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Liu, S.H.; Li, X.G.; Geng, H.; Xie, Y.; He, Y.H. Estimating Maize Yield in the Black Soil Region of Northeast China Using Land Surface Data Assimilation: Integrating a Crop Model and Remote Sensing. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 915109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.Y.; Fan, R.Q.; Yang, X.M.; Zhang, Z.H.; Zhang, X.Q.; Liang, A.Z. Decomposition of Maize Stover Varies With Maize Type and Stover Management Strategies: A Microcosm Study on a Black Soil (Mollisol) in Northeast China. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 234, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuchenbuch, R.O.; Gerke, H.H.; Buczko, U. Spatial Distribution of Maize Roots by Complete 3D Soil Monolith Sampling. Plant Soil 2009, 315, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Wang, X.L.; Long, A.R.; Ji, X.J.; Wang, D.C.; Jiang, Y.; Gong, X.W.; Qi, H. Optimizing Nitrogen Management Cooperates Yield Stability and Environmental Nitrogen Balance From the Perspective of Continuous Straw Incorporation. Field Crops Res. 2025, 333, 110121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, L.E.; Flint, A.L. Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 4. Physical Methods; Dane, J.H., Top, G.C., Eds.; SSSA Special Publications: Madison, WI, USA, 2002; pp. 241–253. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, D.; Sommers, L.E. Total Carbon, Organic Carbon, and Organic Matter. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 2. Chemical and Microbiological Properties; SSSA Special Publications: Madison, WI, USA, 1982; pp. 539–579. [Google Scholar]

- Bremner, J. Determination of Nitrogen in Soil by the Kjeldahl Method. J. Agric. Sci. 1960, 55, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motsara, M.R.; Roy, R.N. Guide to Laboratory Establishment for Plant Nutrient Analysis; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hedley, M.J.; Stewart, J.W.B. Method to Measure Microbial Phosphate in Soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1982, 14, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorich, R.A.; Nelson, D.W. Evaluation of Manual Cadmium Reduction Methods for Determination of Nitrate in Potassium Chloride Extracts of Soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1984, 48, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Ma, H.; Xie, Y.; Jia, X.; Su, T.; Li, J.; Shen, Y. Assessment of Soil Quality Indexes for Different Land Use Types in Typical Steppe in the Loess Hilly Area, China. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 118, 106743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.J.; Liu, S.W.; Zhang, L.; Li, Q.; Zhou, D.W. Selecting the Minimum Data Set and Quantitative Soil Quality Indexing of Alkaline Soils Under Different Land Uses in Northeastern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 616–617, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S.S.; Karlen, D.L.; Mitchell, J.P. A Comparison of Soil Quality Indexing Methods for Vegetable Production Systems in Northern California. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2002, 90, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, M.S.; Holden, N.M. Indices for Quantitative Evaluation of Soil Quality Under Grassland Management. Geoderma 2014, 230–231, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzyakov, Y.; Gunina, A.; Zamanian, K.; Tian, J.; Luo, Y.; Xu, X.L.; Yudina, A.; Aponte, H.; Alharbi, H.; Ovsepyan, L.; et al. New Approaches for Evaluation of Soil Health, Sensitivity and Resistance to Degradation. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2020, 7, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balesdent, J.; Chenu, C.; Balabane, M. Relationship of Soil Organic Matter Dynamics to Physical Protection and Tillage. Soil Tillage Res. 2000, 53, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidela Hussein, M.; Muche, H.; Schmitter, P.; Nakawuka, P.; Tilahun, S.A.; Langan, S.; Barron, J.; Steenhuis, T.S. Deep Tillage Improves Degraded Soils in the Sub-Humid Ethiopian Highlands. Land 2019, 8, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ussiri, D.A.N.; Lal, R. Long-Term Tillage Effects on Soil Carbon Storage and Carbon Dioxide Emissions in Continuous Corn Cropping System From an Alfisol in Ohio. Soil Tillage Res. 2009, 104, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, P.X.; Li, R.P.; Zheng, H.B.; Wang, H.; Yuan, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zheng, J.Y.; Liu, W.R. Long-Term Conservation Tillage Practices Directly and Indirectly Affect Soil Micro-Food Web in a Chinese Mollisol. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A. Annual Crop Residue Production and Nutrient Replacement Costs for Bioenergy Feedstock Production in United States. Agron. J. 2013, 105, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.; Wang, L.; Jia, R.; Zhou, J.; Zang, H.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Peixoto, L.; et al. Straw Returning With No-Tillage Alleviates Microbial Metabolic Carbon Limitation and Improves Soil Multifunctionality in the Northeast Plain. Land Degrad. Dev. 2024, 35, 5149–5161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tu, C.; Cheng, L.; Li, C.; Gentry, L.F.; Hoyt, G.D.; Zhang, X.; Hu, S. Long-Term Impact of Farming Practices on Soil Organic Carbon and Nitrogen Pools and Microbial Biomass and Activity. Soil Tillage Res. 2011, 117, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Sheng, Z.; Zheng, L.; Zheng, X.; Yang, Y.; Xiao, D.; Ai, B.; Zeng, H. Impacts of 25-Year Rotation and Tillage Management on Soil Quality in a Semi-Arid Tropical Climate. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2021, 81, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vian, J.F.; Peigne, J.; Chaussod, R.; Roger-Estrade, J. Effects of Four Tillage Systems on Soil Structure and Soil Microbial Biomass in Organic Farming. Soil Use Manag. 2009, 25, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Zhou, W.; Gu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Xue, Y.; Shi, Z.; Siddique, K.H.M. Effects of Tillage Regime on Soil Aggregate-Associated Carbon, Enzyme Activity, and Microbial Community Structure in a Semiarid Agroecosystem. Plant Soil 2024, 498, 543–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Peng, C.; Zhang, W.; Li, S.; An, T.; Xu, Y.; Ge, Z.; Xie, N.; Wang, J. Subsoiling Tillage With Straw Incorporation Improves Soil Microbial Community Characteristics in the Whole Cultivated Layers: A One-Year Study. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 215, 105188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; Sun, J.; Liu, Z.; He, X.; Qiao, J. Effects of Tillage and Sowing Methods on Soil Physical Properties and Corn Plant Characters. Agriculture 2023, 13, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.M.; Wang, Y.M.; Qiu, G.W.; Yu, H.J.; Liu, F.M.; Wang, G.L.; Duan, Y. Conservation Tillage Facilitates the Accumulation of Soil Organic Carbon Fractions by Affecting the Microbial Community in an Eolian Sandy Soil. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1394179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, G.; Shu, H.; Hu, W.; Han, H.; Liu, R.; Guo, Z. Straw Return Increases Crop Production by Improving Soil Organic Carbon Sequestration and Soil Aggregation in a Long-Term Wheat-Cotton Cropping System. J. Integr. Agric. 2024, 23, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhao, S.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Pan, X.; He, F.; van der Ploeg, M. Impact of Long-Term Sub-Soiling Tillage on Soil Porosity and Soil Physical Properties in the Soil Profile. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 2892–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getahun, G.T.; Kätterer, T.; Munkholm, L.J.; Rychel, V.; Kirchmann, H. Effects of Loosening Combined With Straw Incorporation Into the Upper Subsoil on Soil Properties and Crop Yield in a Three-Year Field Experiment. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 223, 105466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvedev, V.V. Physical Properties and Spatial Distribution of the Plowpan in Different Arable Soils. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2011, 44, 1364–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.Z.; Li, X.; Dong, S.T.; Liu, P.; Zhan, B.; Zhang, J.W. Soil Physical Properties and Maize Root Growth Under Different Tillage Systems in the North China Plain. Crop J. 2018, 6, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Pang, D.W.; Chen, J.; Luo, Y.L.; Zheng, M.J.; Yin, Y.P.; Li, Y.X.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.L. Straw Return Accompany With Low Nitrogen Moderately Promoted Deep Root. Field Crops Res. 2018, 221, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, A.L.; Lynch, J.P.; Brown, K.M. Spatial Distribution and Phenotypic Variation in Root Cortical Aerenchyma of Maize (Zea mays L.). Plant Soil 2013, 367, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, D.H.; Jia, G.P.; Cai, L.J.; Ma, Z.Y.; Eneji, A.E.; Cui, Y.H. Effects of Tillage Practices on Root Characteristics and Root Lodging Resistance of Maize. Field Crops Res. 2016, 185, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpare, F.V.; van Lier, Q.D.J.; de Camargo, L.; Pires, R.C.M.; Ruiz-Correa, S.T.; Bezerra, A.H.F.; Gava, G.J.C.; Dias, C.T.D.S. Tillage Effects on Soil Physical Condition and Root Growth Associated With Sugarcane Water Availability. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 187, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, V.A.; Ordóñez, R.A.; Wright, E.E.; Castellano, M.J.; Liebman, M.; Hatfield, J.L.; Helmers, M.; Archontoulis, S.V. Maize Root Distributions Strongly Associated With Water Tables in Iowa, USA. Plant Soil 2019, 444, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Pang, Y. Droplet Breakup in an Asymmetric Bifurcation With Two Angled Branches. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2018, 188, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frelih-Larsen, A.; Hinzmann, M.; Ittner, S. The ‘Invisible’ Subsoil: An Exploratory View of Societal Acceptance of Subsoil Management in Germany. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canisares, L.P.; Grove, J.; Miguez, F.; Poffenbarger, H. Long-Term No-Till Increases Soil Nitrogen Mineralization but Does Not Affect Optimal Corn Nitrogen Fertilization Practices Relative to Inversion Tillage. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 213, 105080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Yang, N.; Lu, C.; Qin, X.; Siddique, K.H. Soil Organic Carbon, Total Nitrogen, Available Nutrients, and Yield Under Different Straw Returning Methods. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 214, 105171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Song, F.; Wang, Z.; Qi, Z.; Liu, M.; Guan, S.; Sun, J.; Li, S.; Zhao, J. Effects of Different Straw Return Methods on the Soil Structure, Organic Carbon Content and Maize Yield of Black Soil Farmland. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Wu, L.; Dong, F.; Yan, S.; Li, F.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Huang, X. Subsoil Tillage Enhances Wheat Productivity, Soil Organic Carbon and Available Nutrient Status in Dryland Fields. J. Integr. Agric. 2024, 23, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Nie, L.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, S.; Yang, H.; Guo, L.; Xia, J.; Ning, T.; Jiao, N.; Kuzyakov, Y. Long-Term Subsoiling and Straw Return Increase Soil Organic Carbon Fractions and Crop Yield. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2023, 78, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Code | Operation Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Conventional tillage | CT | After maize harvest in autumn, all aboveground straw is removed from the field. In spring, a rotary tiller is used for shallow stubble breaking and ridge formation, with an operating depth of 15 cm. The resulting ridges are 65 cm in width and 15 cm in height. During ridge preparation, compound fertilizer is applied in a single operation. Conventional seeders are used for sowing on the ridges, after which a land roller is employed for soil compaction. |

| No-tillage with straw mulching | NTS | During the autumn mechanical harvest, all straw is chopped to segments ≤ 5 cm in length, is evenly spread on the soil surface, and receives no further treatment. In spring, no-till planters are used for flat planting with a row spacing of 65 cm. |

| Subsoiling tillage with straw mulching | STS | The traditional 65 cm row spacing is reconfigured into a wide–narrow row pattern for flat cultivation, comprising a 90 cm wide row (straw band) and a 40 cm narrow row (seedling band). In spring, no-till planting is carried out in the previous year’s wide rows using a no-till planter. During the maize jointing stage, deep tillage is performed to a depth of 30–35 cm within the wide rows. After maize harvest, the aboveground straw is retained on the stubble band, while the seedling band is cleared. The following spring, a no-till planter is used to sow seeds in the narrow rows of the seedling band. |

| Harrow tillage with straw mulching and incorporation | HTS | During the autumn mechanical harvest, all straw is chopped into segments less than 20 cm in length and evenly distributed over the soil surface. A harrow-integrated combined tiller is then used for soil preparation, resulting in approximately 30% of the straw remaining on the surface and the remaining 70% being uniformly incorporated into the 0–20 cm tillage layer. In spring, a seedbed preparation machine is employed to further loosen the soil to a depth of 6–12 cm, creating a fine and firm seedbed suitable for sowing. Flat planting is subsequently carried out using a no-till planter with a row spacing of 65 cm. |

| Moldboard plowing tillage with straw incorporation | MPS | During mechanical harvesting, straw is subsequently chopped in a separate operation using a straw shredder. Prior to soil freezing, deep tillage is performed with a subsoiler to a depth of 30–35 cm. Following tillage, a heavy-duty harrow is used to level the soil surface and complete seedbed preparation. In spring, planting is carried out with a no-till planter at a row spacing of 65 cm. |

| Year | Treatment | No. of Spikes (No. ×103·ha−1) | Kernels Per Spike (No.) | Hundred-Kernel Weight (g) | Yield (kg·ha−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT | 52.83 ± 2.47 a | 532.87 ± 14.17 b | 30.92 ± 1.48 a | 10,358.58 ± 194.39 a | |

| NTS | 51.00 ± 2.29 a | 578.93 ± 29.80 a | 31.04 ± 0.43 a | 10,336.46 ± 500.97 a | |

| 2023 | STS | 56.00 ± 3.50 a | 544.40 ± 22.22 b | 32.65 ± 0.12 a | 10,942.37 ± 257.26 a |

| HTS | 52.17 ± 1.44 a | 540.80 ± 9.27 b | 31.66 ± 0.28 a | 10,583.09 ± 323.34 a | |

| MPS | 53.00 ± 3.50 a | 541.93 ± 39.43 b | 31.46 ± 0.52 a | 10,297.48 ± 924.35 a | |

| CT | 53.00 ± 2.50 a | 594.01 ± 13.00 c | 30.13 ± 0.85 b | 8969.84 ± 705.30 b | |

| NTS | 50.17 ± 2.26 a | 649.48 ± 5.14 a | 28.59 ± 0.92 b | 8970.81 ± 661.99 b | |

| 2024 | STS | 52.17 ± 1.89 a | 620.32 ± 45.05 abc | 32.94 ± 0.76 a | 10,654.73 ± 772.08 a |

| HTS | 49.83 ± 4.54 a | 632.61 ± 30.39 abc | 31.81 ± 0.93 ab | 9583.18 ± 987.13 ab | |

| MPS | 51.33 ± 1.26 a | 623.57 ± 6.67 b | 33.02 ± 1.13 a | 10,065.24 ± 24.32 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuan, Y.; Sui, P.; Ren, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Lv, Q.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zheng, J. Effects of Tillage Practices on Soil Quality and Maize Yield in the Semi-Humid Region of Northeast China. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2851. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122851

Yuan Y, Sui P, Ren Y, Wang H, Liu X, Lv Q, Li M, Wang Y, Luo Y, Zheng J. Effects of Tillage Practices on Soil Quality and Maize Yield in the Semi-Humid Region of Northeast China. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2851. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122851

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Ye, Pengxiang Sui, Ying Ren, Hao Wang, Xiaodan Liu, Qiao Lv, Mingsen Li, Yongjun Wang, Yang Luo, and Jinyu Zheng. 2025. "Effects of Tillage Practices on Soil Quality and Maize Yield in the Semi-Humid Region of Northeast China" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2851. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122851

APA StyleYuan, Y., Sui, P., Ren, Y., Wang, H., Liu, X., Lv, Q., Li, M., Wang, Y., Luo, Y., & Zheng, J. (2025). Effects of Tillage Practices on Soil Quality and Maize Yield in the Semi-Humid Region of Northeast China. Agronomy, 15(12), 2851. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122851