Targeted Phosphorus Fertilization in the Peanut Pod Zone Modulates Pod Nutrient Allocation and Reshapes the Geocarposphere Microbial Community

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

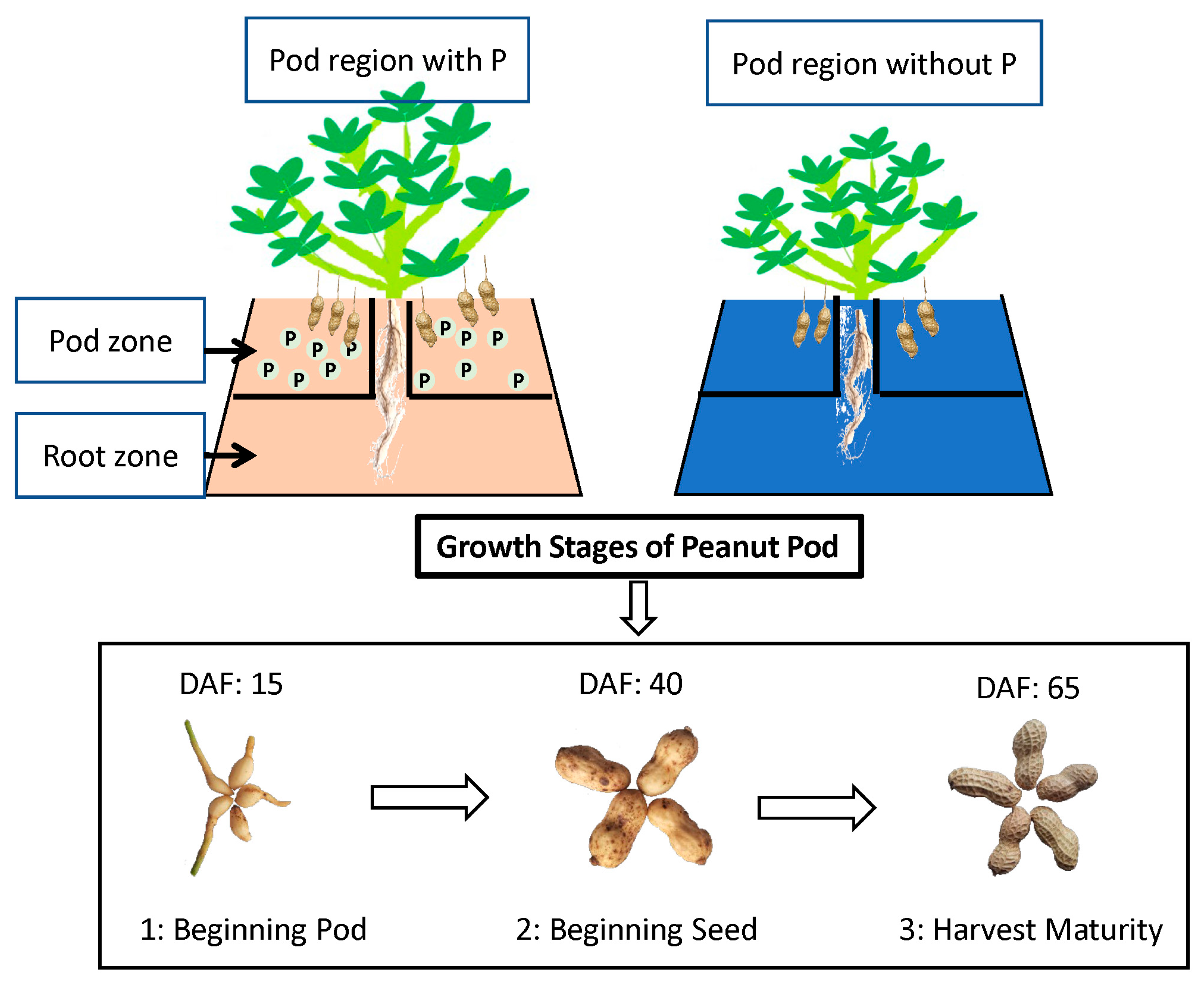

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Properties of Soil and Peanut Pods

2.4. Plant Phenotype Detection

2.5. Root System Scan

2.6. DNA Extraction, PCR and Fungene Sequencing

2.7. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis and Bioinformatics Analysis

3. Results

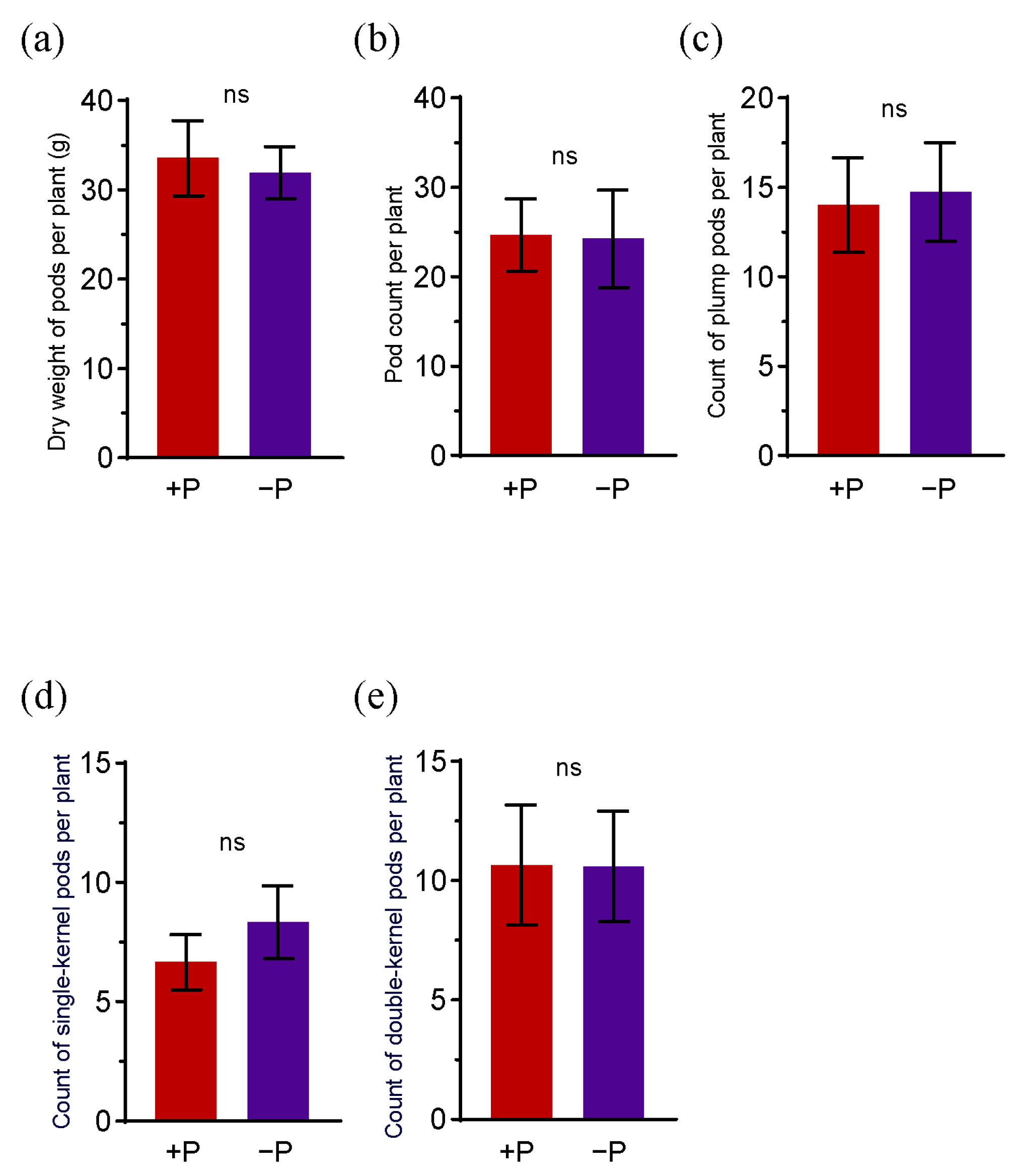

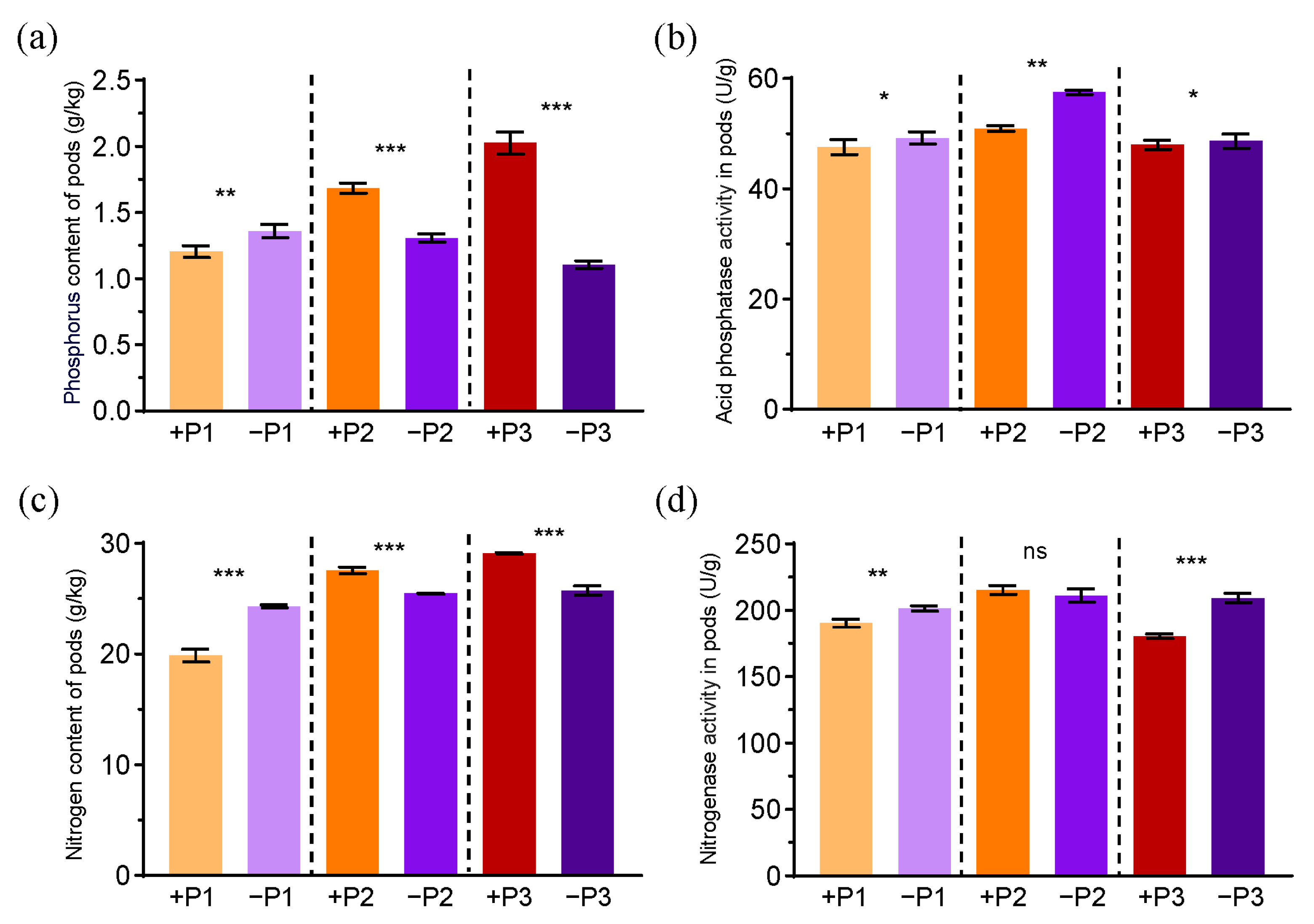

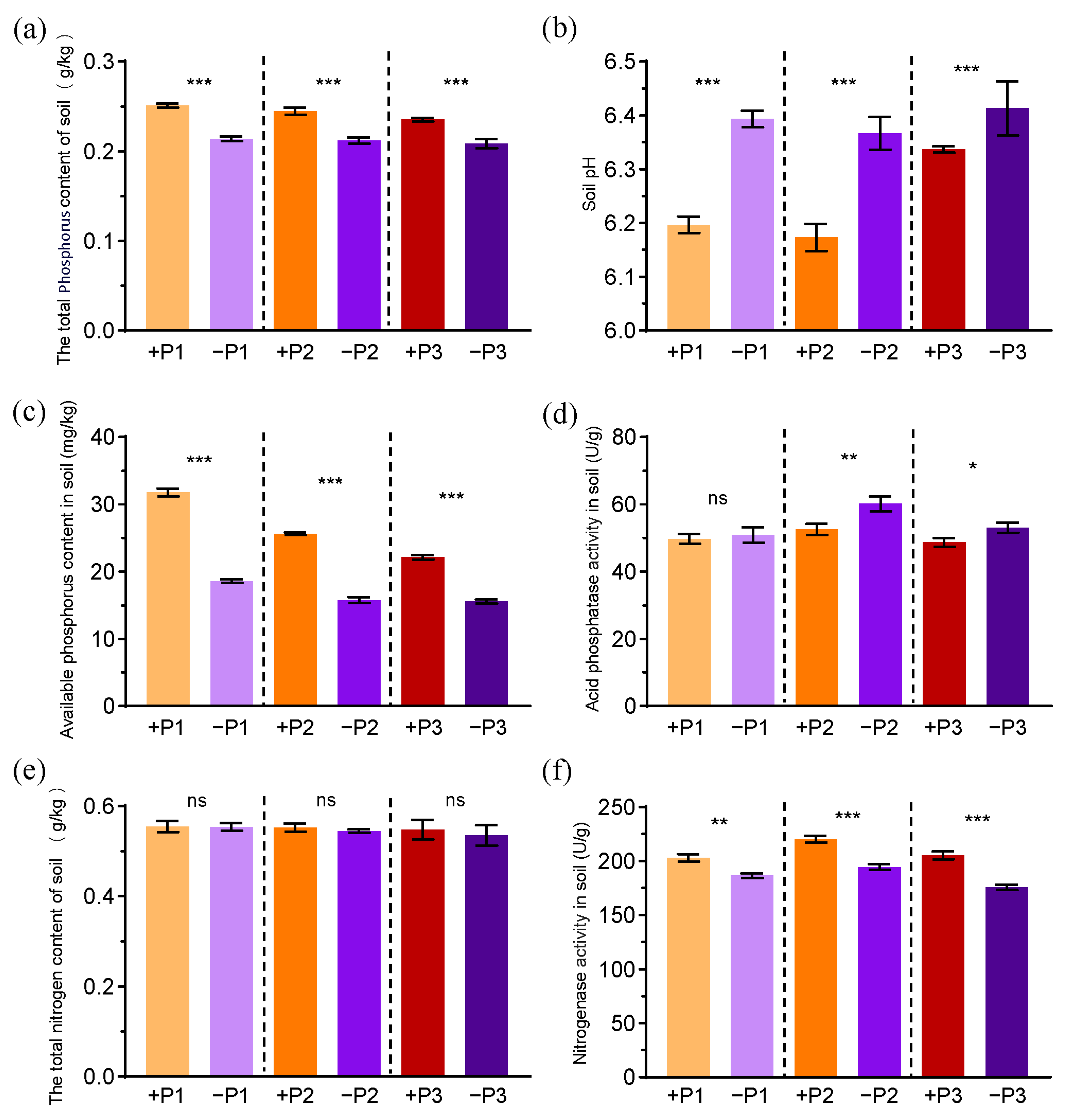

3.1. The Effects of Applying Phosphorus Fertilizer on Pod Development and Soil Parameters

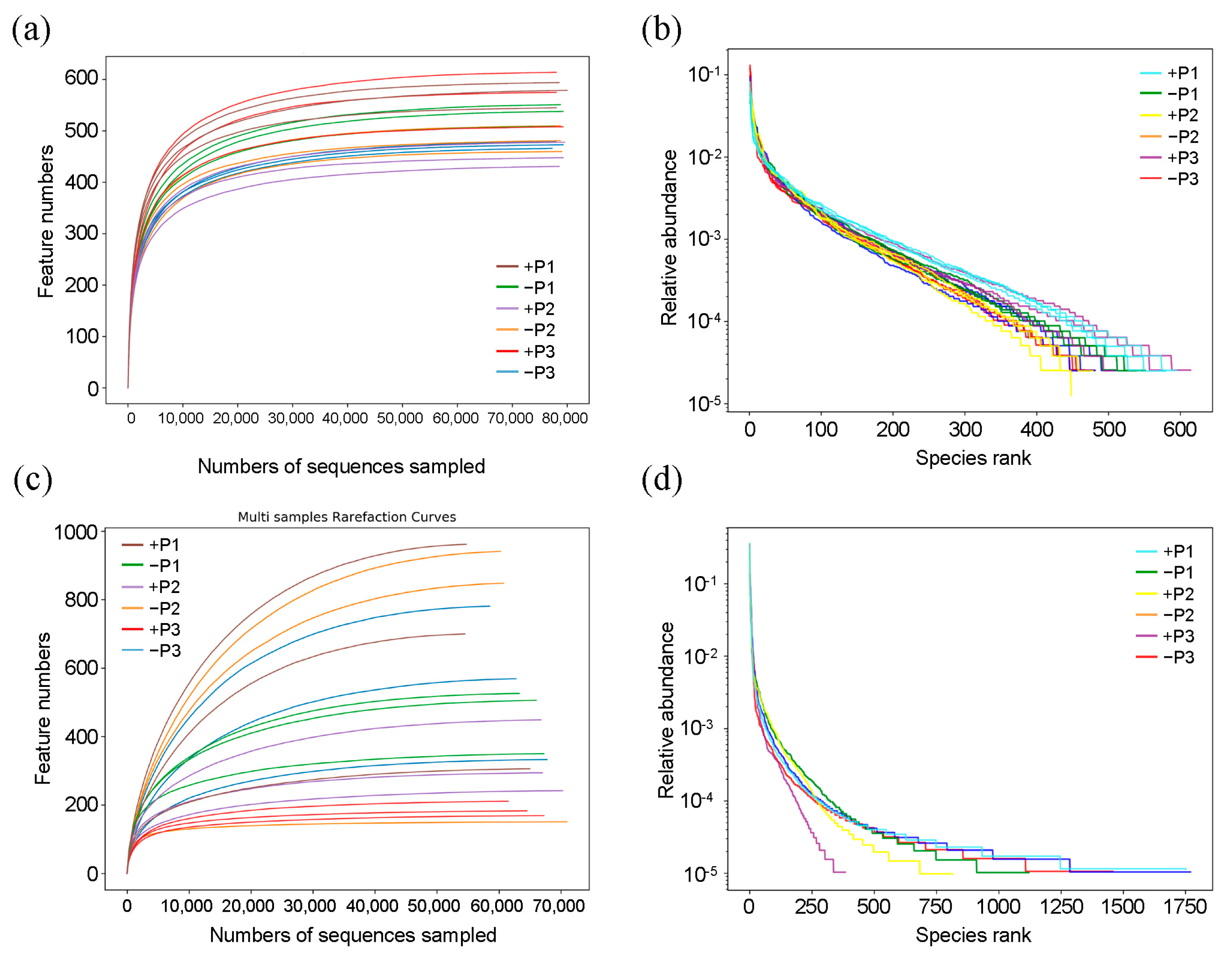

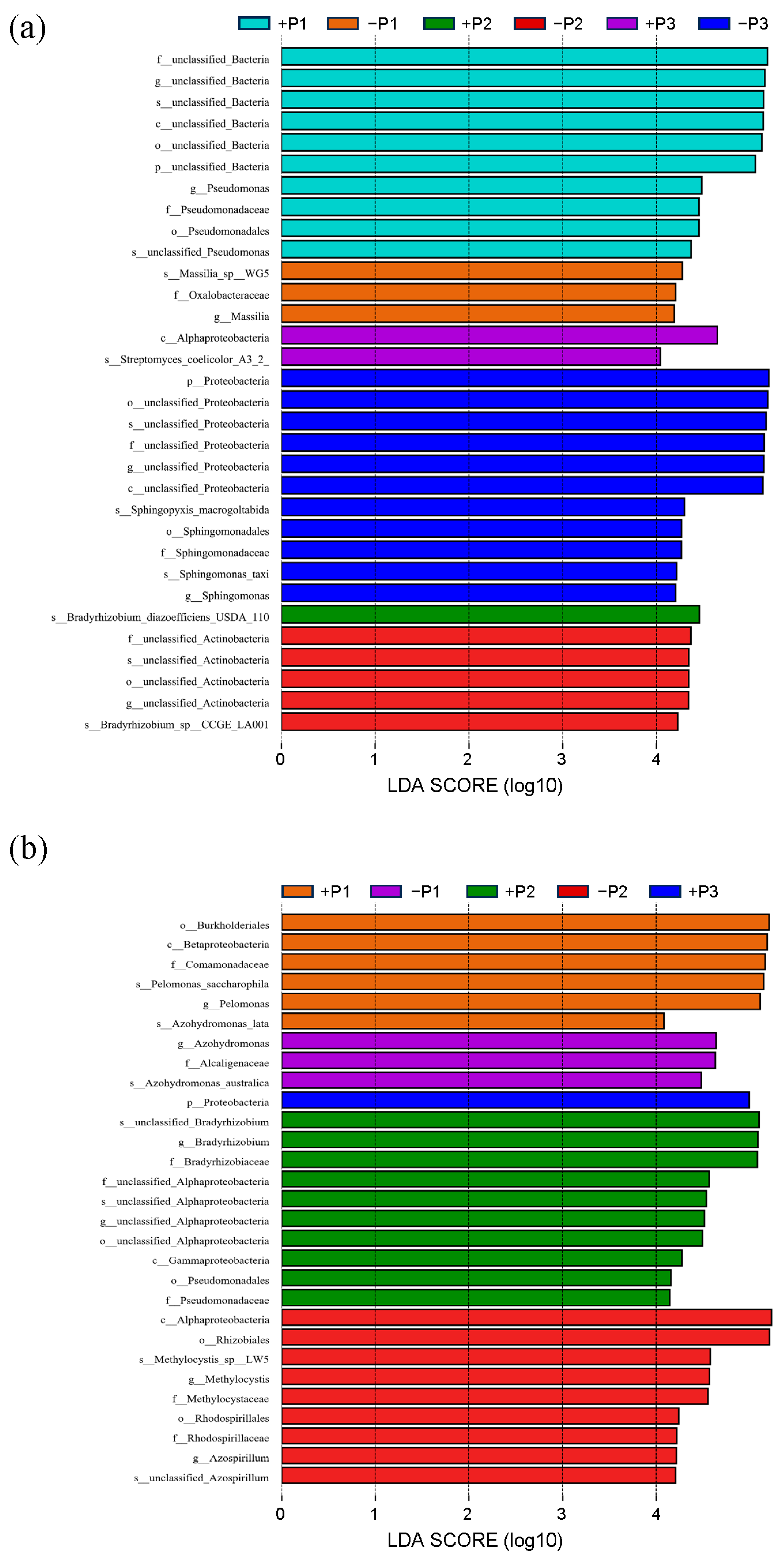

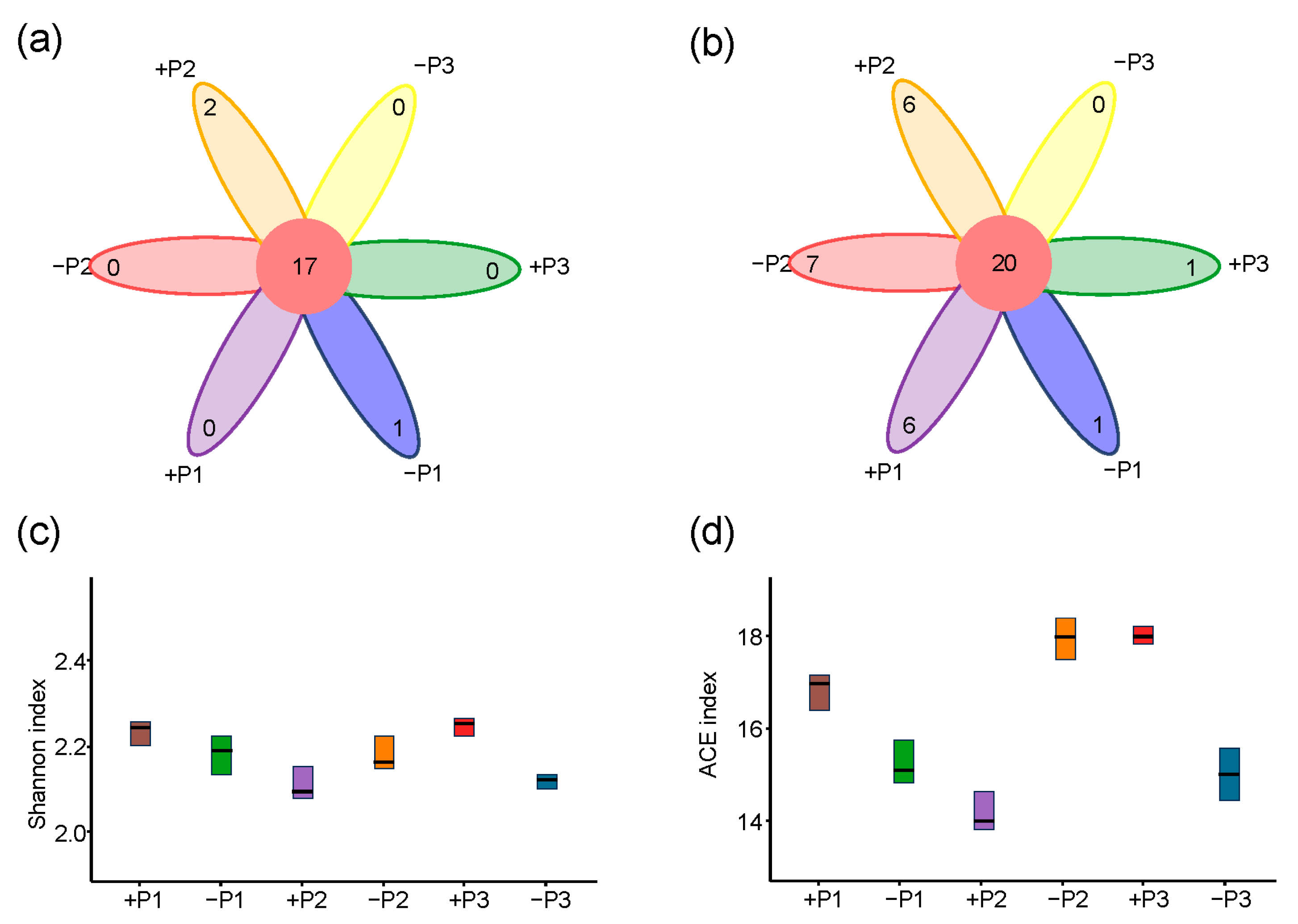

3.2. The Effect of Applying Phosphorus Fertilizer in the Peanut Pod Zone on PSB and NFB in the Soil Surrounding the Pods

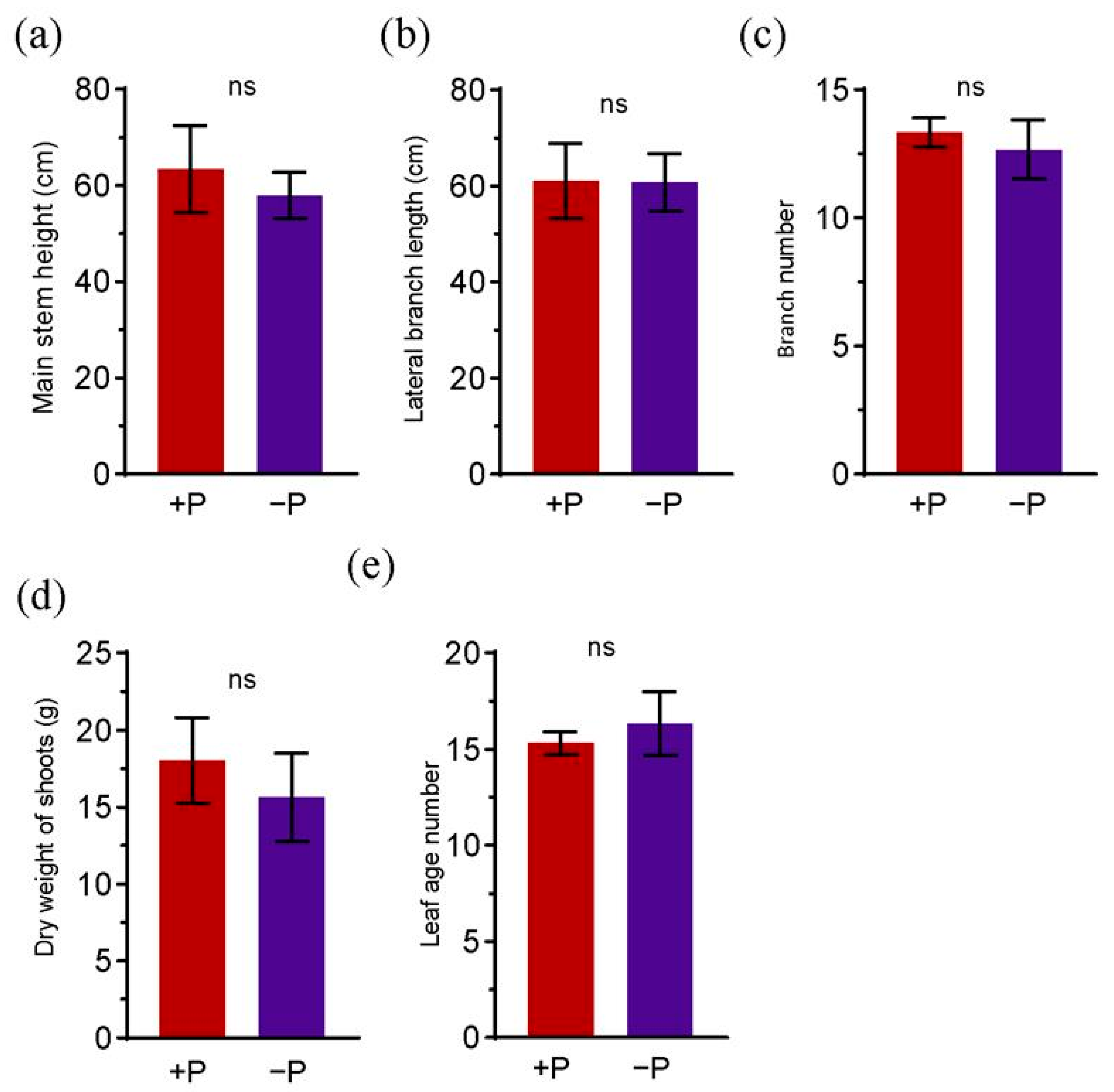

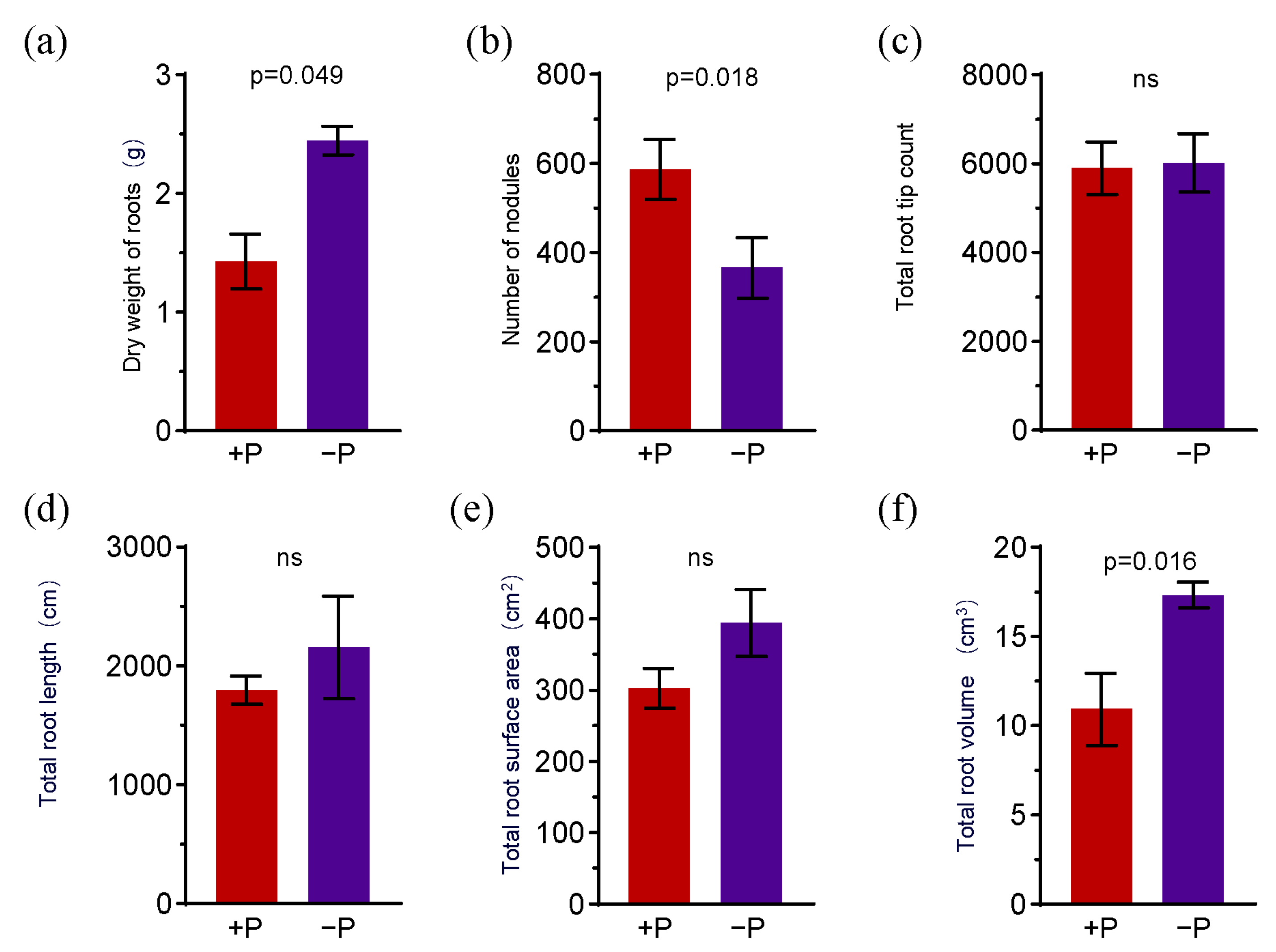

3.3. The Effects of Phosphorus Fertilizer Application in the Peanut Pod Zone on Physiological Indices of Peanut Aerial and Root Components

4. Discussion

4.1. Peanut Pods Can Directly Absorb Phosphorus from the Soil to Support the Growth and Development of the Kernels

4.2. The Alterations in the Community of PSB in the Geocarposphere Suggest That Peanut Pods Possess an Autonomous Mechanism for Regulating the Uptake of Phosphorus Elements

4.3. The Inhibition of Peanut Root Development and the Fluctuation in the Abundance of NFB in the Peanut Geocarposphere Indicate the Correlation Between Peanut Absorption of Various Elements

4.4. The Capacity of Peanut Pods to Directly Absorb Nutrients from the External Environment Is Worthy of Exploration, as It Can Significantly Enhance Both the Yield and Quality of Peanuts

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PSB | Phosphorus Solubilizing Bacteria |

| NFB | Nitrogen Fixing Bacteria |

Appendix A

References

- Akram, N.A.; Shafiq, F.; Ashraf, M. Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.): A Prospective Legume Crop to Offer Multiple Health Benefits under Changing Climate. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2018, 17, 1325–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojiewo, C.O.; Janila, P.; Bhatnagar-Mathur, P.; Pandey, M.K.; Desmae, H.; Okori, P.; Varshney, R.K. Advances in Crop Improvement and Delivery Research for Nutritional Quality and Health Benefits of Groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toomer, O.T. Nutritional Chemistry of the Peanut (Arachis hypogaea). Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 3042–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthika, K.S.; Rashmi, I.; Parvathi, M.S. Biological Functions, Uptake and Transport of Essential Nutrients in Relation to Plant Growth. In Plant Nutrients and Abiotic Stress Tolerance; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kambiranda, D.M.; Vasanthaiah, H.K.; Katam, R.; Ananga, A.; Basha, S.M.; Naik, K. Impact of Drought Stress on Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) Product. Food Safety. Plants Environ. 2011, 1, 249–272. [Google Scholar]

- Crusciol, C.A.C.; Portugal, J.R.; Bossolani, J.W.; Moretti, L.G.; Fernandes, A.M.; Garcia, J.L.N.; Cantarella, H. Dynamics of Macronutrient Uptake and Removal by Modern Peanut Cultivars. Plants 2021, 10, 2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, H.; Vandana; Sharma, S.; Pandey, R. Phosphorus Nutrition: Plant Growth in Response to Deficiency and Excess. In Plant Nutrients and Abiotic Stress Tolerance; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 171–190. [Google Scholar]

- Raven, J.A. Interactions between Nitrogen and Phosphorus Metabolism. In Annual Plant Reviews: Phosphorus Metabolism in Plants; Plaxton, W.C., Lambers, H., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2015; Volume 48, pp. 187–214. [Google Scholar]

- Kamara, E.G.; Olympio, N.S.; Asibuo, J.Y. Effect of Calcium and Phosphorus Fertilizer on the Growth and Yield of Groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Int. Res. J. Agric. Sci. Soil Sci. 2011, 1, 326–331. [Google Scholar]

- Aulakh, M.S.; Kabba, B.S.; Baddesha, H.S.; Bahl, G.S.; Gill, M.P.S. Crop Yields and Phosphorus Fertilizer Transformations after 25 Years of Applications to a Subtropical Soil under Groundnut-Based Cropping Systems. Field Crops Res. 2003, 83, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Shen, J.; Zhang, J.; Zuo, Y.; Li, L.; Chen, X. Rhizosphere Processes and Management for Improving Nutrient Use Efficiency and Crop Productivity: Implications for China. Adv. Agron. 2010, 107, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.N.; Mohammad, F. Eutrophication: Challenges and Solutions. In Eutrophication: Causes, Consequences and Control; Ansari, A.A., Gill, S.S., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, R.; Yeasmin, S.; Islam, A.K.M.M.; Sarkar, M.R. Effect of Phosphorus, Calcium and Boron on the Growth and Yield of Groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Int. J. Bio-Sci. Bio-Technol. 2013, 5, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.B.; Liu, W.X.; Li, Z.G.; Teng, Y.; Luo, Y.M. Effects of Long-Term Fertilizer Applications on Peanut Yield and Quality and Plant and Soil Heavy Metal Accumulation. Pedosphere 2020, 30, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadirimangalam, S.R.; Sawargaonkar, G.; Choudhari, P. Morphological and Molecular Insights of Calcium in Peanut Pod Development. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 9, 100320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissuwa, M.; Ae, N. Genotypic Variation for Phosphorus Uptake from Hardly Soluble Iron-Phosphate in Groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Plant Soil 1999, 206, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Peng, M.; Liu, Z.; Shah, S.S. The Role of Soil Microbes in Promoting Plant Growth. Mol. Microbiol. Res. 2017, 7, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, P.; Das, S.; Shankhdhar, D.; Shankhdhar, S.C. Phosphate-Solubilizing Microorganisms: Mechanism and Their Role in Phosphate Solubilization and Uptake. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2021, 21, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, K.; Kumari, B.; Mallick, M.A. Phosphate Solubilizing Microbes: An Effective and Alternative Approach as Biofertilizers. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 8, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Olivares, J.; Bedmar, E.J.; Sanjuán, J. Biological Nitrogen Fixation in the Context of Global Change. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2013, 26, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franche, C.; Lindström, K.; Elmerich, C. Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria Associated with Leguminous and Non-Leguminous Plants. Plant Soil 2009, 321, 35–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clevenger, J.; Chu, Y.; Scheffler, B.; Ozias-Akins, P. A Developmental Transcriptome Map for Allotetraploid Arachis hypogaea. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.L.; Chen, C.Y.; Tonnis, B.; Pinnow, D.; Davis, J.; An, Y.Q.C.; Dang, P. Changes of Seed Weight, Fatty Acid Composition, and Oil and Protein Contents from Different Peanut FAD2 Genotypes at Different Seed Developmental and Maturation Stages. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 3658–3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.; Rangani, J.; Kumari, A.; Parida, A.K. Mineral Nutrient Homeostasis, Photosynthetic Performance, and Modulations of Antioxidative Defense Components in Two Contrasting Genotypes of Arachis hypogaea L. (Peanut) for Mitigation of Nitrogen and/or Phosphorus Starvation. J. Biotechnol. 2020, 323, 136–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.; Xia, H.; Christie, P.; Zhang, L.; Li, L. Crop Acquisition of Phosphorus, Iron and Zinc from Soil in Cereal/Legume Intercropping Systems: A Critical Review. Ann. Bot. 2016, 117, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smal, H.; Kvien, C.S.; Sumner, M.E.; Csinos, A.S. Solution Calcium Concentration and Application Date Effects on Pod Calcium Uptake and Distribution in Florunner and Tifton-8 Peanut. J. Plant Nutr. 1989, 12, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Bai, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, F. Phosphorus Dynamics: From Soil to Plant. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizcano-Toledo, R.; Reyes-Martín, M.P.; Celi, L.; Fernández-Ondoño, E. Phosphorus Dynamics in the Soil–Plant–Environment Relationship in Cropping Systems: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Peng, S.; Hua, Q.; Qiu, C.; Wu, P.; Liu, X.; Lin, X. The Long-Term Effects of Using Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria and Photosynthetic Bacteria as Biofertilizers on Peanut Yield and Soil Bacteria Community. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 693535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etesami, H. Enhanced Phosphorus Fertilizer Use Efficiency with Microorganisms. In Nutrient Dynamics for Sustainable Crop Production; Meena, R.S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 215–245. [Google Scholar]

- Lucero, C.T.; Lorda, G.S.; Anzuay, M.S.; Ludueña, L.M.; Taurian, T. Peanut Endophytic Phosphate Solubilizing Bacteria Increase Growth and P Content of Soybean and Maize Plants. Curr. Microbiol. 2021, 78, 1961–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.Y.; Wang, M.L.; Sun, X.X.; Shu, C.L.; Zhang, J.; Geng, L.L. Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) Pod and Rhizosphere Harbored Different Bacterial Communities. Rhizosphere 2021, 19, 100373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzuay, M.S.; Viso, N.P.; Ludueña, L.M.; Morla, F.D.; Angelini, J.G.; Taurian, T. Plant Beneficial Rhizobacteria Community Structure Changes through Developmental Stages of Peanut and Maize. Rhizosphere 2021, 19, 100407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badar, R.; Nisa, Z.; Ibrahim, S. Supplementation of P with Rhizobial Inoculants to Improve Growth of Peanut Plants. Int. J. Appl. Res. 2015, 1, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sindhu, S.S.; Phour, M.; Choudhary, S.R.; Chaudhary, D. Phosphorus Cycling: Prospects of Using Rhizosphere Microorganisms for Improving Phosphorus Nutrition of Plants. In Geomicrobiology and Biogeochemistry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 199–237. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Wang, T.; Chi, X.; Wang, M.; Chen, N.; Chen, M.; Qi, P.; Xu, H. Isolation and Characterization of Halotolerant Phosphate Solubilizing Bacteria Naturally Colonizing the Peanut Rhizosphere in Salt-Affected Soil. Geomicrobiol. J. 2020, 37, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Inukai, Y.; Yamauchi, A. Root Development and Nutrient Uptake. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2006, 25, 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajima, R.; Abe, J.; Lee, O.N.; Morita, S.; Lux, A. Developmental Changes in Peanut Root Structure during Root Growth and Root-Structure Modification by Nodulation. Ann. Bot. 2008, 101, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Smith, C.J. Modelling the Growth and Water Uptake Function of Plant Root Systems: A Review. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 2004, 55, 501–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Luo, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, M.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, F. Study on the Relationship of Root Morphology and Phosphorus Absorption Efficiency with Phosphorus Uptake Capacity in 235 Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) Germplasms. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 855815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Yang, L.; Wu, Q.; Meng, C.; Zhang, J.; Shen, P. Regulation of the C:N Ratio Improves the N-Fixing Bacteria Activity, Root Growth, and Nodule Formation of Peanut. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 4596–4608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Zahra, N.; Hafeez, M.B.; Ahmad, M.; Iqbal, S.; Shaukat, K.; Ahmad, G. Nitrogen Fixation of Legumes: Biology and Physiology. In The Plant Family Fabaceae: Biology and Physiological Responses to Environmental Stresses; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 43–74. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, W.; Pablo, G.P.; Jun, Y.; Danfeng, H. Abundance and Diversity of Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria in Rhizosphere and Bulk Paddy Soil under Different Duration of Organic Management. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 28, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frezarin, E.T.; Santos, C.H.B.; Sales, L.R.; dos Santos, R.M.; de Carvalho, L.A.L.; Rigobelo, E.C. Promotion of Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) Growth by Plant Growth-Promoting Microorganisms. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 14, 316–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboyeji, C.M.; Dunsin, O.; Adekiya, A.O.; Suleiman, K.O.; Chinedum, C.; Okunlola, F.O.; Owolabi, I.O. Synergistic and Antagonistic Effects of Soil Applied P and Zn Fertilizers on the Performance, Minerals and Heavy Metal Composition of Groundnut. Open Agric. 2020, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.S.; Radder, B.M.; Malligawad, L.H.; Manasa, V. Effect of Nitrogen and Phosphorus Levels and Ratios on Yield and Nutrient Uptake by Groundnut in Northern Transition Zone of Karnataka. Bioscan 2014, 9, 1561–1564. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, M.J.; Bell, M.J.; Wright, G.C.; Cozens, G.D. Uptake and Partitioning of Cadmium by Cultivars of Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Plant Soil 2000, 222, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, Q.; Shen, P.; Liang, H.; Liu, M.; Chen, D.; Yang, L. Targeted Phosphorus Fertilization in the Peanut Pod Zone Modulates Pod Nutrient Allocation and Reshapes the Geocarposphere Microbial Community. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2850. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122850

Wu Q, Shen P, Liang H, Liu M, Chen D, Yang L. Targeted Phosphorus Fertilization in the Peanut Pod Zone Modulates Pod Nutrient Allocation and Reshapes the Geocarposphere Microbial Community. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2850. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122850

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Qi, Pu Shen, Haiyan Liang, Miao Liu, Dianxu Chen, and Liyu Yang. 2025. "Targeted Phosphorus Fertilization in the Peanut Pod Zone Modulates Pod Nutrient Allocation and Reshapes the Geocarposphere Microbial Community" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2850. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122850

APA StyleWu, Q., Shen, P., Liang, H., Liu, M., Chen, D., & Yang, L. (2025). Targeted Phosphorus Fertilization in the Peanut Pod Zone Modulates Pod Nutrient Allocation and Reshapes the Geocarposphere Microbial Community. Agronomy, 15(12), 2850. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122850