National-Scale Assessment of Soil pH Change in Chinese Croplands from 1980 to 2018

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil pH Datasets

2.2. pH Classification, Transitions, and Change Rates

2.3. Soil pH Risk Zoning Based on Current Status and Temporal Change

3. Results

3.1. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Cropland Soil pH in CHINA

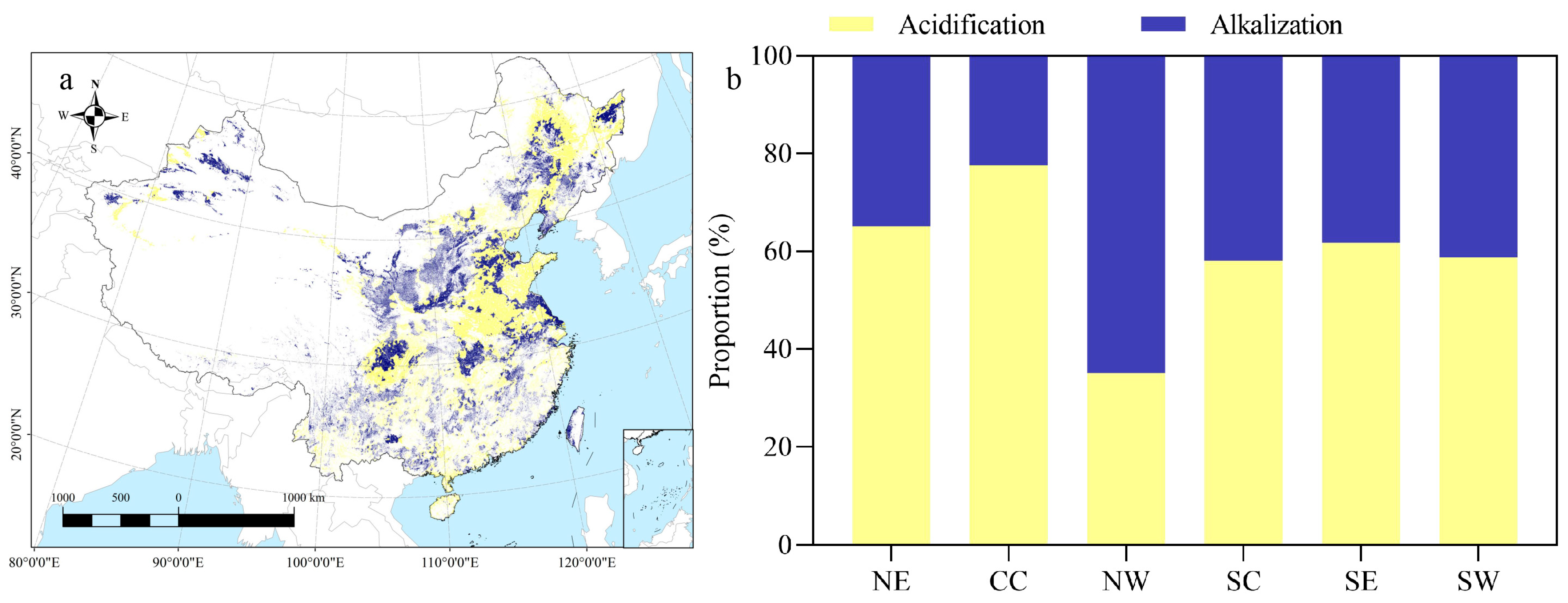

3.2. National and Regional Transitions of Cropland Soil pH

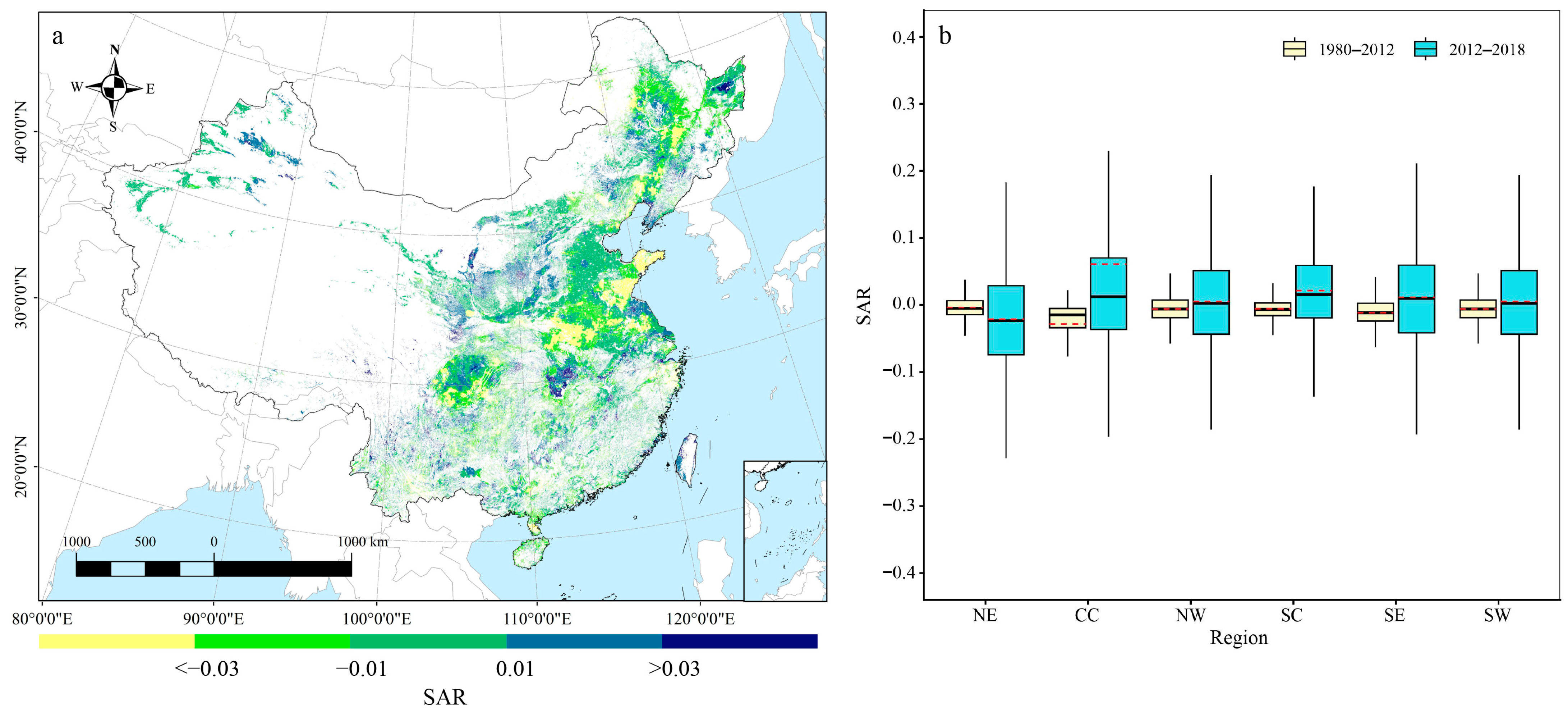

3.3. Spatiotemporal Changes in Cropland Soil pH

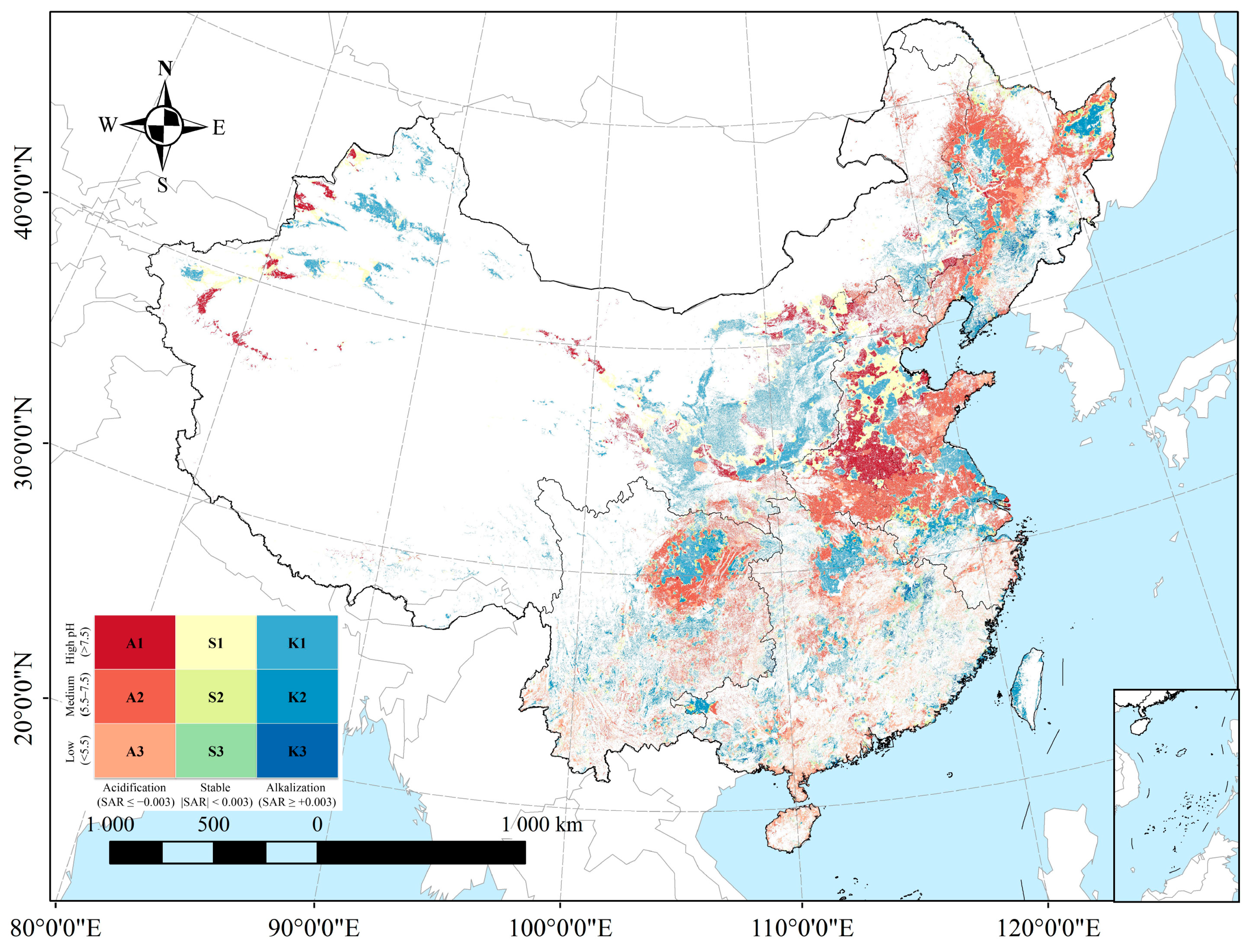

3.4. Spatial Patterns and Typology of Soil pH Risk Zones

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Naz, M.; Hussain, S.; Tariq, M.; Danish, S.; Khan, I. The soil pH and heavy metals revealed their impact on soil microbial community. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 321, 115770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slessarev, E.W.; Lin, Y.; Bingham, N.L.; Johnson, J.E.; Dai, Y.; Schimel, J.P.; Chadwick, O.A. Water balance creates a threshold in soil pH at the global scale. Nature 2016, 540, 567–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, J.; Duarte, C.M. Drivers of pH variability in coastal ecosystems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 4020–4029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisman, V.; Muresan, A.C.; Bogatu, N.L.; Herbei, E.E.; Buruiana, D.L. Recent advances in the remediation of degraded and contaminated soils: A review of sustainable and applied strategies. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Yan, W.; Canisares, L.P.; Wang, S.; Brodie, E.L. Alterations in soil pH emerge as a key driver of the impact of global change on soil microbial nitrogen cycling: Evidence from a global meta-analysis. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2022, 32, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; House, J.I.; Bustamante, M.; Sobocká, J.; Harper, R.; Pan, G.; West, P.C.; Clark, J.M.; Adhya, T.; Rumpel, C.; et al. Global change pressures on soils from land use and management. Glob. Change Biol. 2016, 22, 1008–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Liu, X.J.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, J.L.; Han, W.X.; Zhang, W.F.; Christie, P.; Goulding, K.W.T.; Vitousek, P.M.; Zhang, F.S. Significant acidification in major Chinese croplands. Science 2010, 327, 1008–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xu, W.; Lu, X.; Zhong, B.; Guo, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhao, Y.; He, W.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; et al. Exploring global changes in agricultural ammonia emissions and their contribution to nitrogen deposition since 1980. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2121998119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Yang, J.-L.; Zhao, X.-R.; Yang, S.-H.; Mulder, J.; Dörsch, P.; Peng, X.-H.; Zhang, G.-L. Soil acidification and loss of base cations in a subtropical agricultural watershed. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 827, 154338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Gan, P.; Chen, A. Environmental controls on soil pH in planted forest and its response to nitrogen deposition. Environ. Res. 2019, 172, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, A.W.; Yu, X.L.; Dai, T.F.; Peng, Y.Y.; Yuan, D.; Zhao, B.; Tao, Q.; Wang, C.Q.; Li, B.; et al. Soil acidification of the soil profile across Chengdu Plain of China from the 1980s to 2010s. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 698, 134320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Xie, E.; Peng, Y.; Yan, G.; Jiang, J.; Hu, W.; Zhao, Y. Four-dimensional modelling reveals decline in cropland soil pH during last four decades in China’s Mollisols region. Geoderma 2025, 453, 117135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.G.; Huggins, D.R.; Reganold, J.P. Linking soil health and ecological resilience to achieve agricultural sustainability. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2023, 21, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Sun, X.; Sun, Y.; Yan, J.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, J. Soil acidification and factors controlling topsoil pH shift of cropland in central China from 2008 to 2018. Geoderma 2022, 408, 115654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, A.; Zulfiqar, A.; Saleem, M.Z.; Ali, B.; Saleem, M.H.; Ali, S.; Tufekci, E.D.; Tufekci, A.R.; Rahimi, M.; Mostafa, R.M. Alkaline and acidic soil constraints on iron accumulation by rice cultivars in relation to several physio-biochemical parameters. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojorquez-Quintal, E.; Escalante-Magana, C.; Echevarria-Machado, I.; Martinez-Estevez, M. Aluminum, a friend or foe of higher plants in acid soils. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, S.K.; Naamala, J.; Dakora, F.D. Nature and mechanisms of aluminium toxicity, tolerance and amelioration in symbiotic legumes and rhizobia. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2018, 54, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; He, C.; Liu, W.; Liu, W.; Liu, Q.; Bai, W.; Li, L.; Lal, R.; Zhang, H. Responses of soil pH to no-till and the factors affecting it: A global meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn, C.; Camberato, J. A critical review on soil chemical processes that control how soil pH affects phosphorus availability to plants. Agriculture 2019, 9, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Kuzyakov, Y. Soil organic matter priming: The pH effects. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husson, O.; Sarthou, J.-P.; Bousset, L.; Ratnadass, A.; Schmidt, H.-P.; Kempf, J.; Husson, B.; Tingry, S.; Aubertot, J.-N.; Deguine, J.-P.; et al. Soil and plant health in relation to dynamic sustainment of Eh and pH homeostasis: A review. Plant Soil 2021, 466, 391–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ye, C.; Su, Y.; Peng, W.; Lu, R.; Liu, Y.; Huang, H.; He, X.; Yang, M.; Zhu, S. Soil acidification caused by excessive application of nitrogen fertilizer aggravates soil-borne diseases: Evidence from literature review and field trials. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 340, 108205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daba, N.A.; Li, D.; Huang, J.; Han, T.; Zhang, L.; Ali, S.; Khan, M.N.; Du, J.; Liu, S.; Legesse, T.G.; et al. Long-Term Fertilization and Lime-Induced Soil pH Changes Affect Nitrogen Use Efficiency and Grain Yields in Acidic Soil Under Wheat-Maize Rotation. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Richter, D.D.; Mendoza, A.; Heine, P. Effects of land-use history on soil spatial heterogeneity of macro- and trace elements in the Southern Piedmont, USA. Geoderma 2010, 156, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xiang, D.Q.; Yang, C.; Wu, W.; Liu, H.B. The spatial variability of temporal changes in soil pH affected by topography and fertilization. Catena 2022, 218, 106547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, M.N.E.A.; Lobry de Bruyn, L.; Guppy, C.N.; Osanai, Y. Temporal variations of soil organic carbon and pH at landscape scale and the implications for cropping intensity in rice-based cropping systems. Agronomy 2020, 11, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, M.; Wu, M.; Jiang, C.; Chen, X.; Cai, Z.; Wang, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, T.; Li, Z. Soil pH rather than nutrients drive changes in microbial community following long-term fertilization in acidic Ultisols of southern China. J. Soils Sediments 2018, 18, 1853–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W.D.; Zheng, N.; Huo, C.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, H.-D.; Li, Y.-W.; Zang, K.-P.; Wang, J.-Y.; Xu, X.-M. Subsurface pH and carbonate saturation state of aragonite on the Chinese side of the North Yellow Sea: Seasonal variations and controls. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 1103–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perri, S.; Molini, A.; Hedin, L.O.; Porporato, A. Contrasting effects of aridity and seasonality on global salinization. Nat. Geosci. 2022, 15, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jin, X.; Liu, X.; Fu, Y.; Bao, K.; Quan, Z.; Xu, C.; Wang, W.; Lu, G.; Zhang, H. Potassium fulvate alleviates salinity and boosts oat productivity by modifying soil properties and rhizosphere microbial communities in the saline–alkali soils of the Qaidam Basin. Agronomy 2025, 15, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhao, G.; Zheng, Z.; Cai, M.; Zhang, Y. Unraveling four decades of soil acidification on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau: Patterns, drivers, and future projections. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 375, 126324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, M.; Hsieh, E.J.; Tsai, H.H.; Ravindran, A.; Schmidt, W. Alkalinity modulates a unique suite of genes to recalibrate growth and pH homeostasis. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1100701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, N.; Shi, X.; Lock, T.R.; Kallenbach, R.L.; Yuan, Z. Predicted increased P relative to N growth limitation of dry grasslands under soil acidification and alkalinization is ameliorated by increased precipitation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 173, 108828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, C.; Ripple, W.J.; Newsome, T.; Barnard, P.; Beamer, K.; Behl, A.; Bowen, J.; Cooney, M.; Crist, E.; Field, C.; et al. Earth at risk: An urgent call to end the age of destruction and forge a just and sustainable future. PNAS Nexus 2024, 3, pgae106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrunalini, K.; Behera, B.; Jayaraman, S.; Abhilash, P.C.; Dubey, P.K.; Swamy, G.N.; Prasad, J.V.N.S.; Rao, K.V.; Krishnan, P.; Pratibha, G.; et al. Nature-based solutions in soil restoration for improving agricultural productivity. Land Degrad. Dev. 2022, 33, 1269–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwiringiyimana, E.; Lai, H.-W.; Ni, N.; Shi, R.-Y.; Pan, X.-Y.; Gao, J.-N.; Biswash, R.; Li, J.-Y.; Cui, X.-M.; Xu, R.-K. Comparative efficacy of alkaline slag, biomass ash, and biochar application for the amelioration of different acidic soils. Plant Soil 2024, 504, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargaz, A.; Lyamlouli, K.; Chtouki, M.; Zeroual, Y.; Dhiba, D. Soil microbial resources for improving fertilizers efficiency in an integrated plant nutrient management system. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shruthi; Prakash, N.B.; Dhumgond, P.; Goiba, P.K.; Laxmanarayanan, M. The benefits of gypsum for sustainable management and utilization of acid soils. Plant Soil 2024, 504, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.A.; Webster, R. A tutorial guide to geostatistics: Computing and modelling variograms and kriging. Catena 2014, 113, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadavecchia, L.; Williams, M. Can spatio-temporal geostatistical methods improve high-resolution regionalisation of meteorological variables? Agric. For. Meteorol. 2012, 149, 1105–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandian, K.; Mustaffa, M.R.A.F.; Mahalingam, G.; Paramasivam, A.; Prince, A.J.; Gajendiren, M.; Mohammad, A.R.R.; Varanasi, S.T. Synergistic conservation approaches for nurturing soil, food security and human health towards sustainable development goals. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2024, 16, 100503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-García, A.; Palomo, I.; Codemo, A.; Rodeghiero, M.; Dubo, T.; Vallet, A.; Lavorel, S. Co-benefits of nature-based solutions exceed the costs of implementation. Cell Rep. Sustain. 2025, 2, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Z.; Yin, Y.; Gong, H.; Wang, H.; Ying, H.; Zhang, H.; Cui, Z. National-Scale Assessment of Soil pH Change in Chinese Croplands from 1980 to 2018. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2775. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122775

Chen Z, Yin Y, Gong H, Wang H, Ying H, Zhang H, Cui Z. National-Scale Assessment of Soil pH Change in Chinese Croplands from 1980 to 2018. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2775. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122775

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Zhong, Yulong Yin, Haiqing Gong, Hongye Wang, Hao Ying, Hongyan Zhang, and Zhenling Cui. 2025. "National-Scale Assessment of Soil pH Change in Chinese Croplands from 1980 to 2018" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2775. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122775

APA StyleChen, Z., Yin, Y., Gong, H., Wang, H., Ying, H., Zhang, H., & Cui, Z. (2025). National-Scale Assessment of Soil pH Change in Chinese Croplands from 1980 to 2018. Agronomy, 15(12), 2775. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122775