Uncertainty Analyses of Arsenic Element Assessments in Cultivated Soils at Different Sampling Densities in High-Altitude Regions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

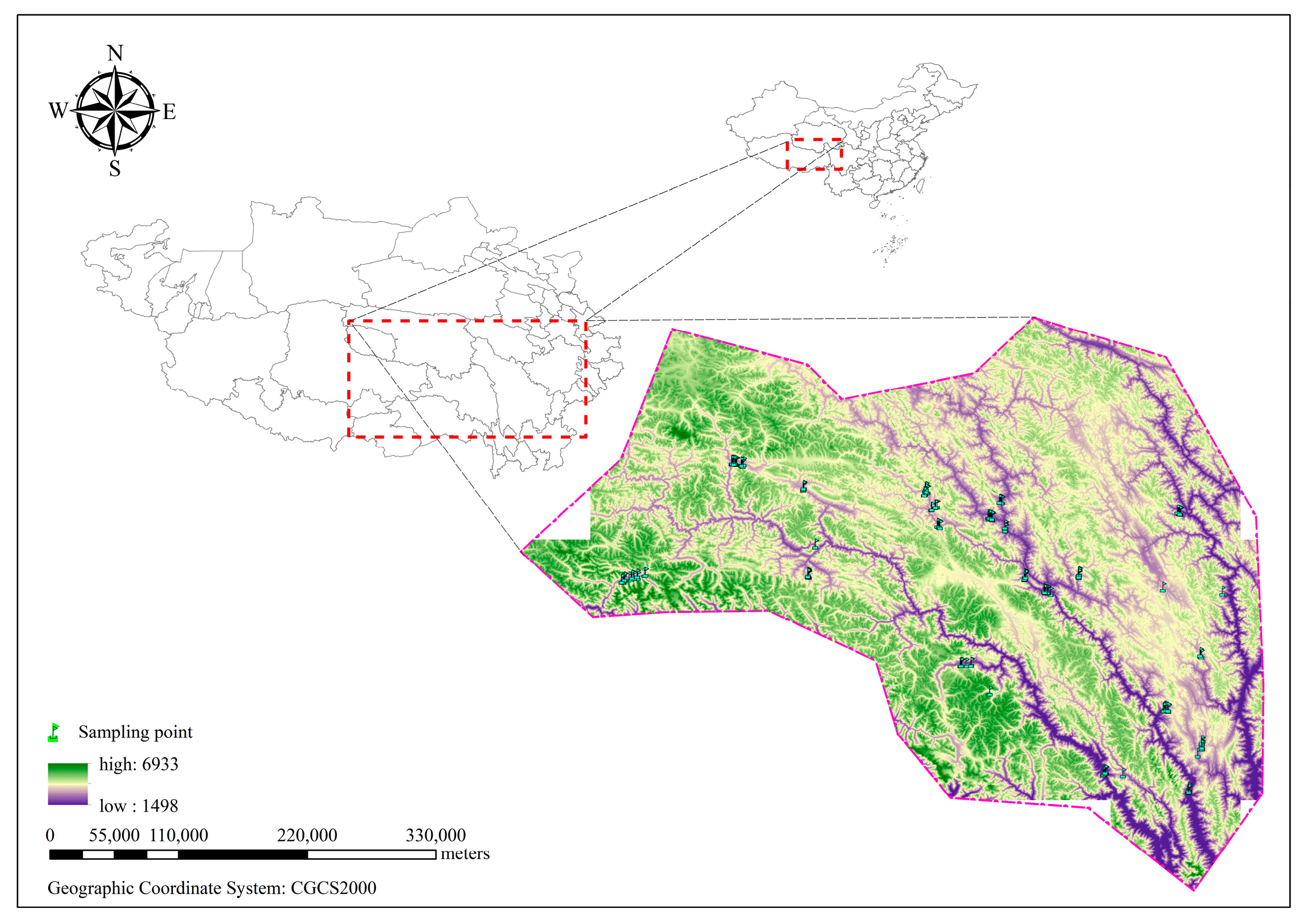

2.1. Research Area Overview

2.2. Site Layout and Sample Collection Monitoring

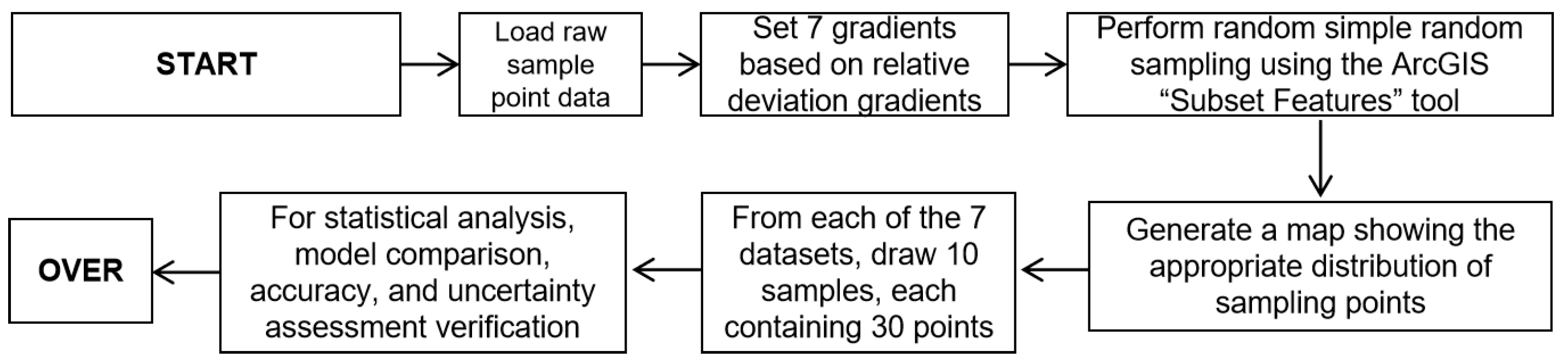

2.3. Setting the Sample Point Density Gradient

2.4. Acceptable Relative Deviation Value

3. Results

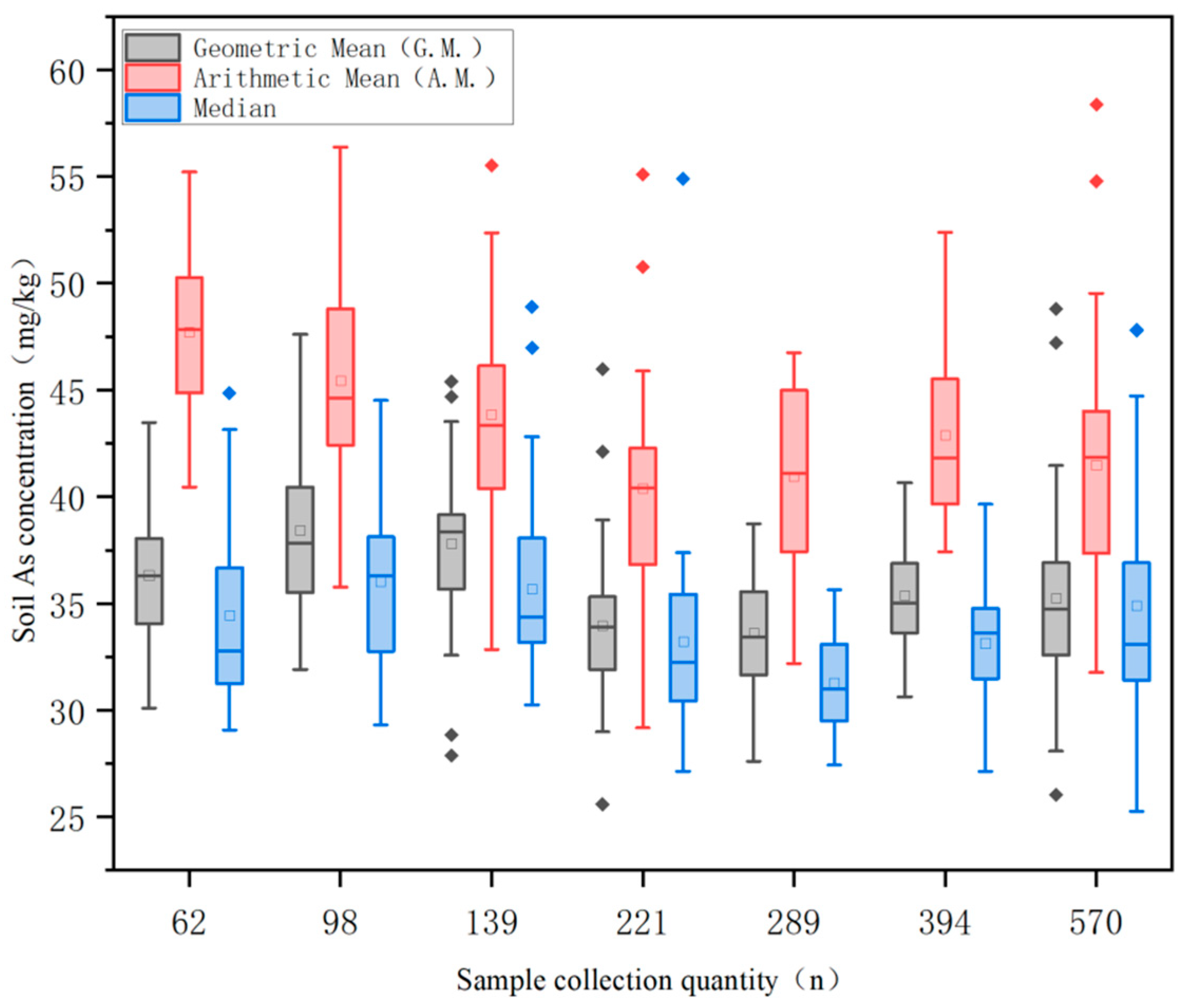

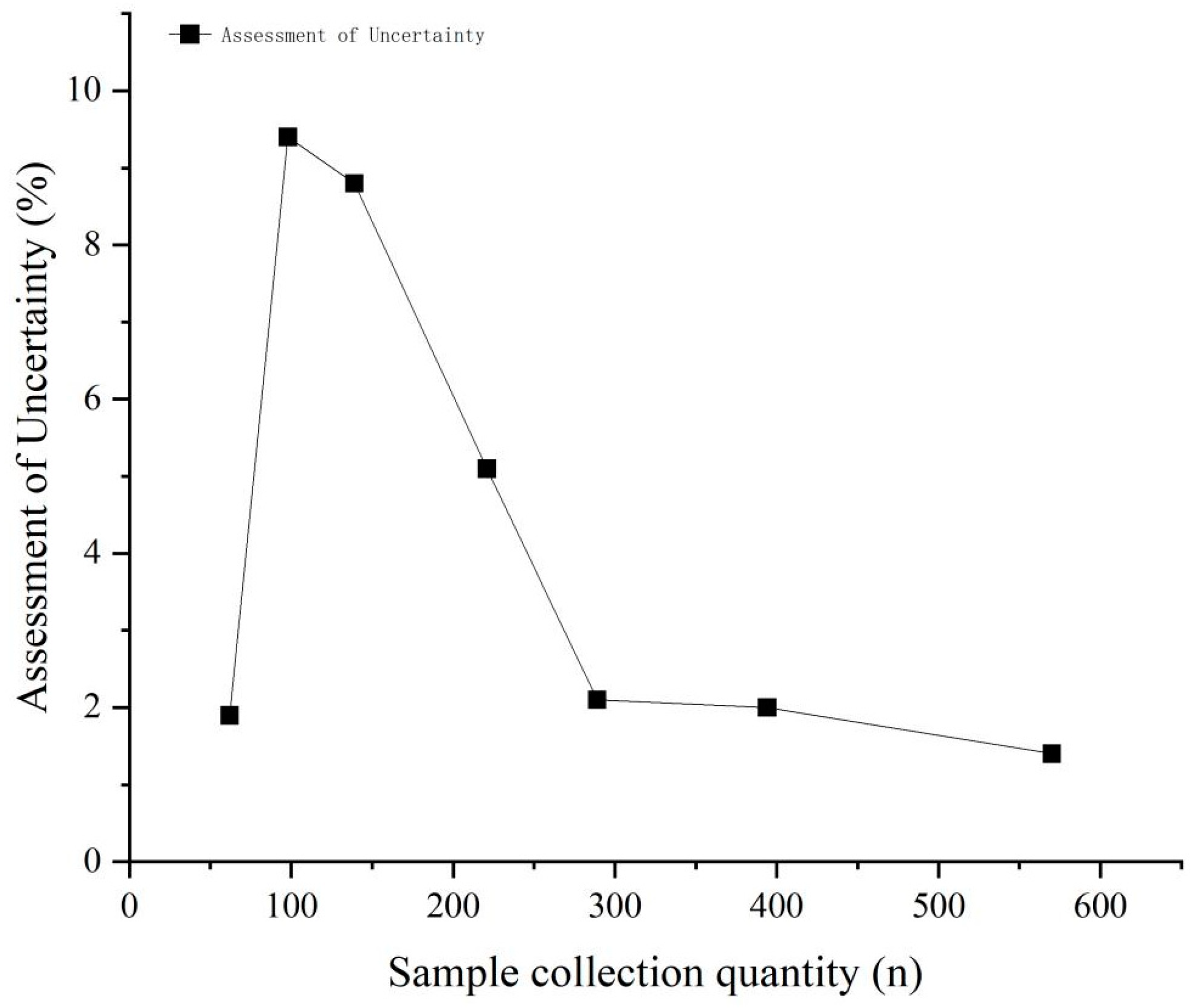

3.1. Uncertainty Analysis of Soil As Concentration Assessment

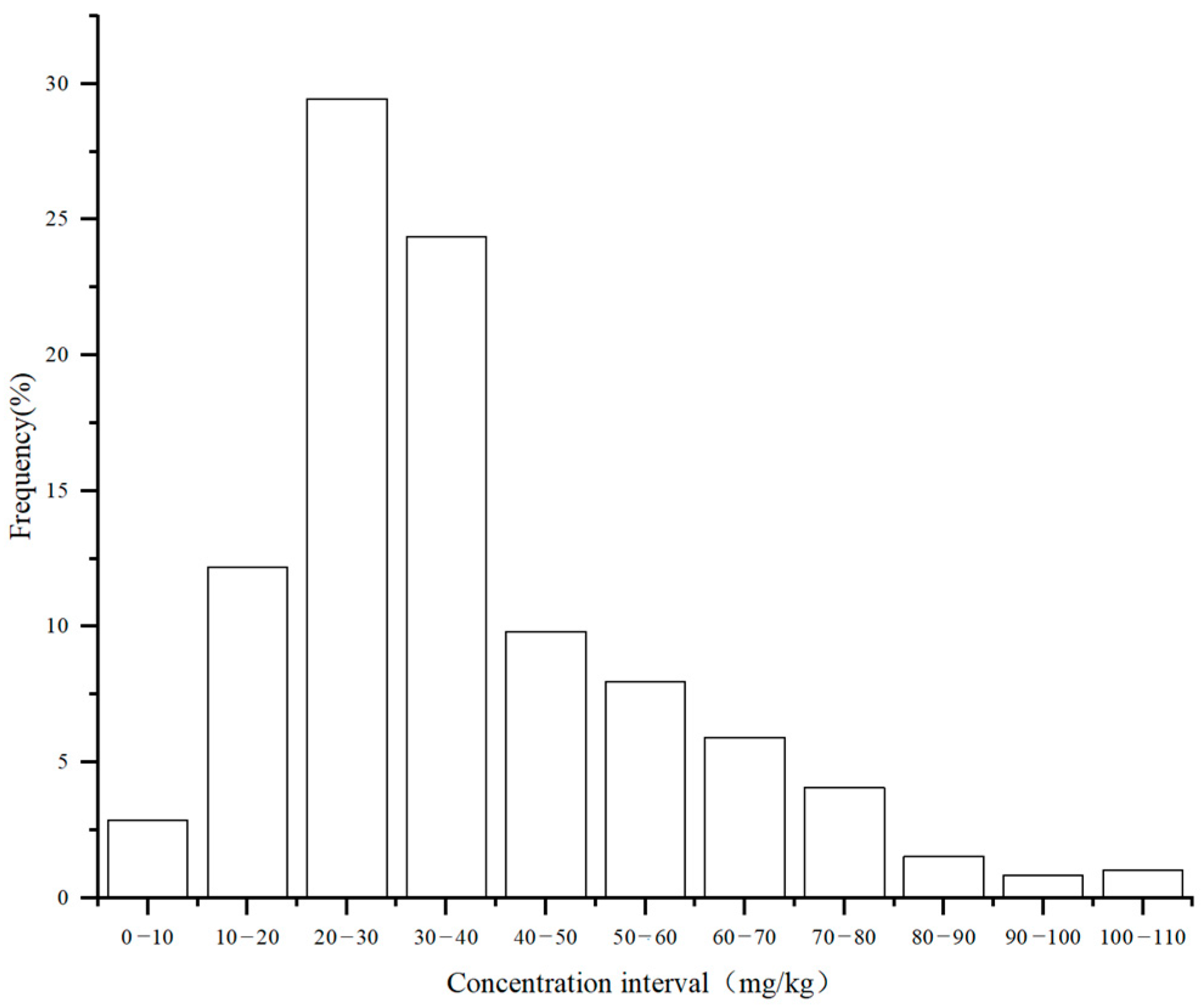

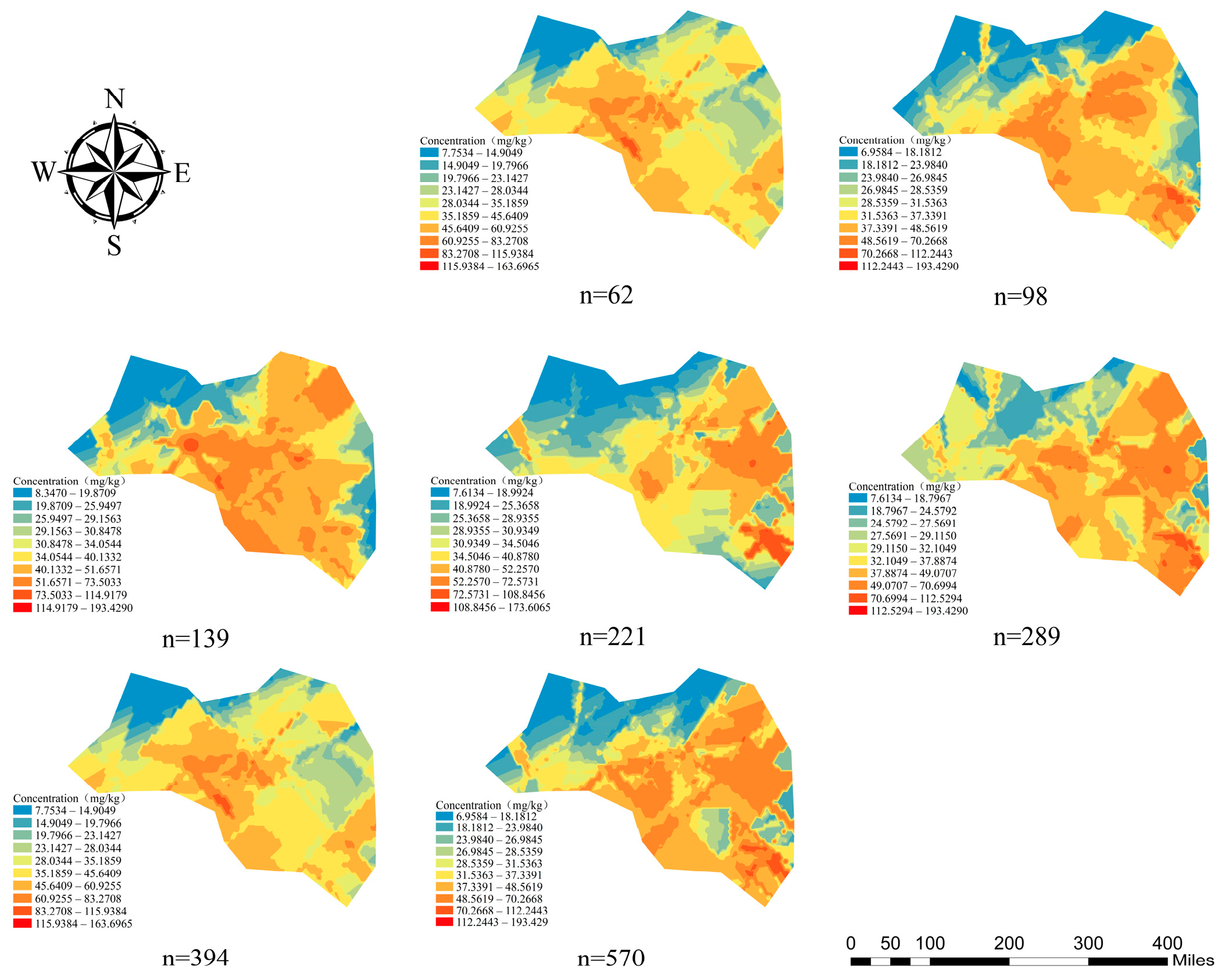

3.2. Soil As Concentration Characteristics and Spatial Distribution Trends

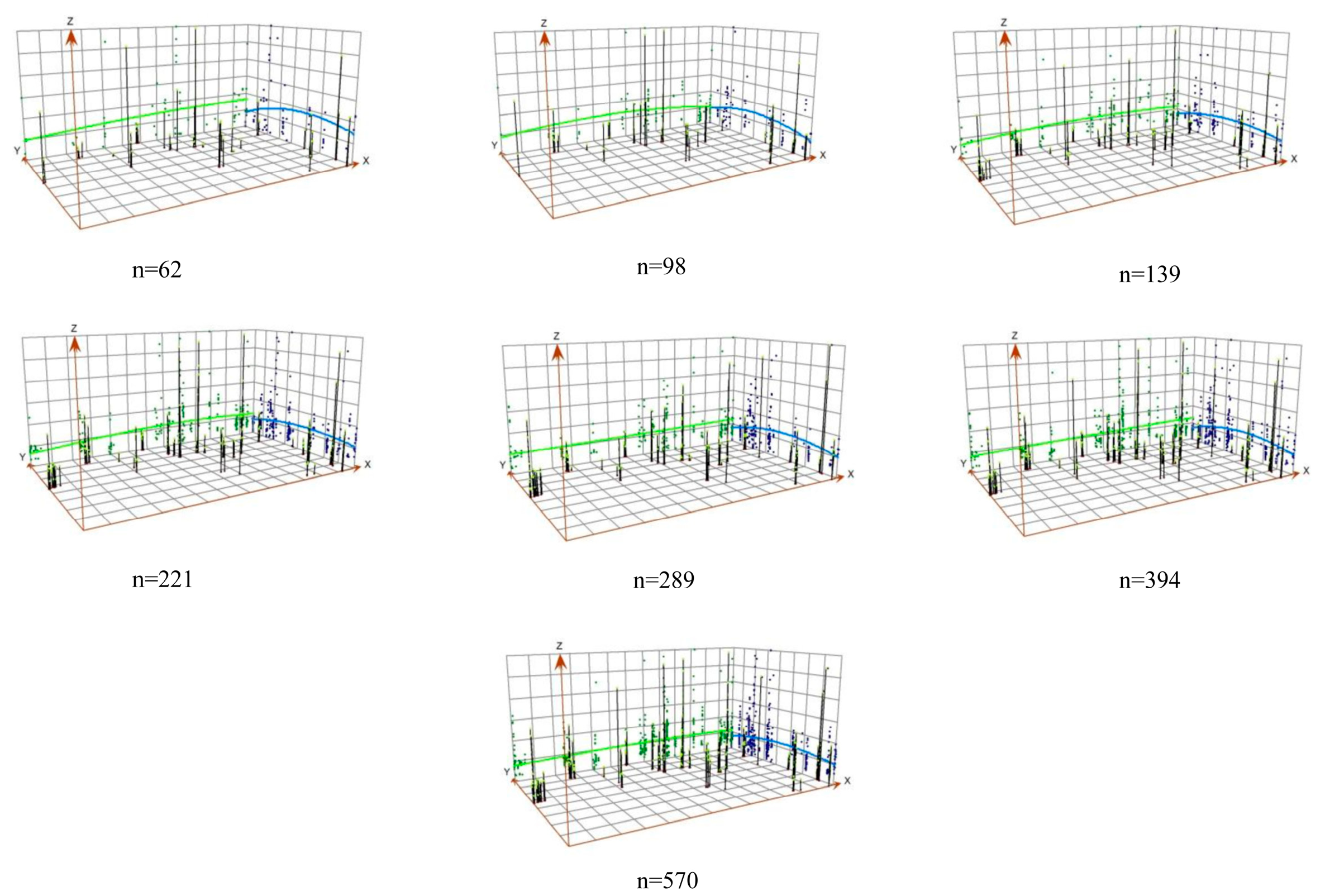

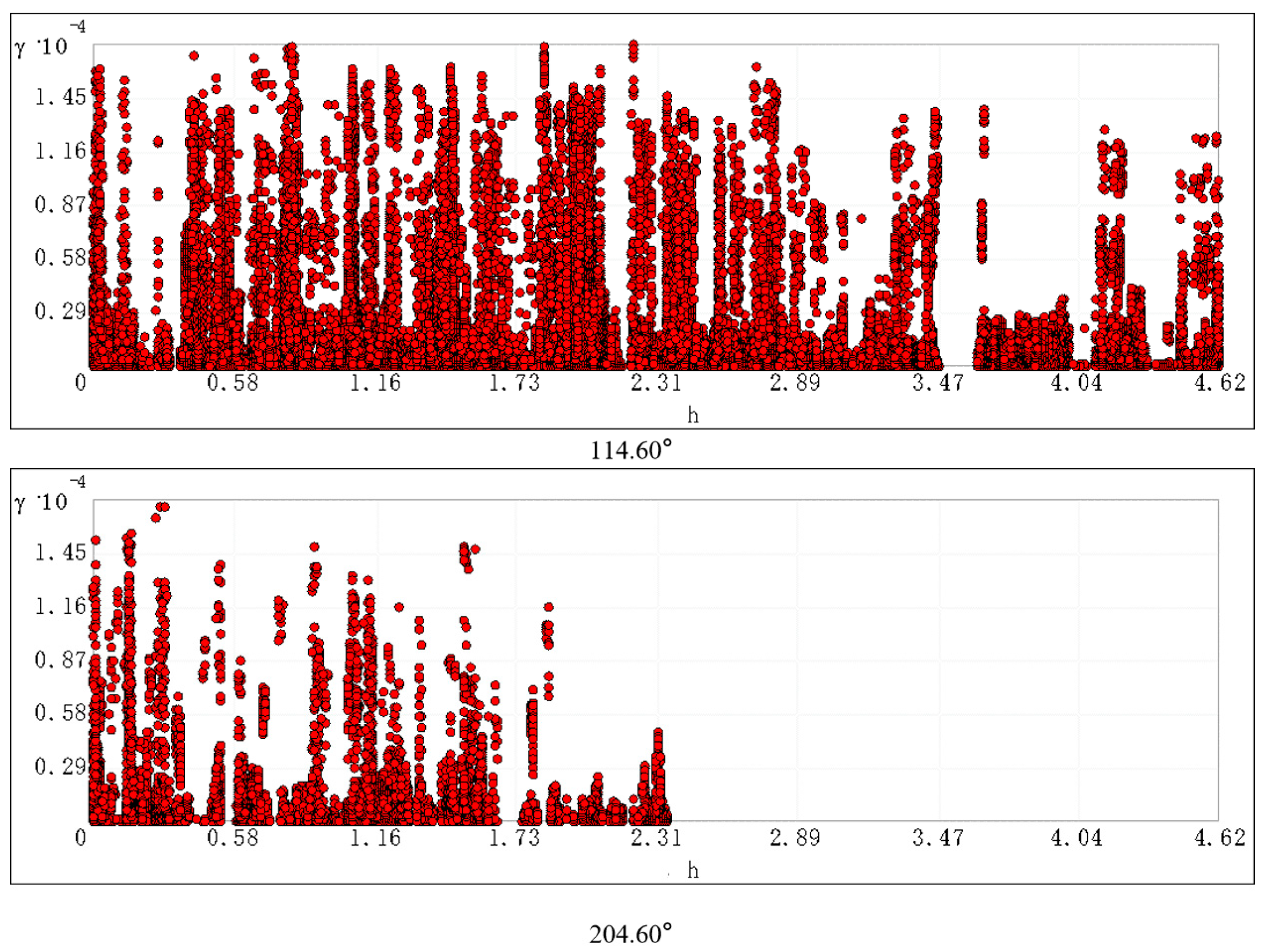

3.3. Spatial Variability Analysis of Soil As

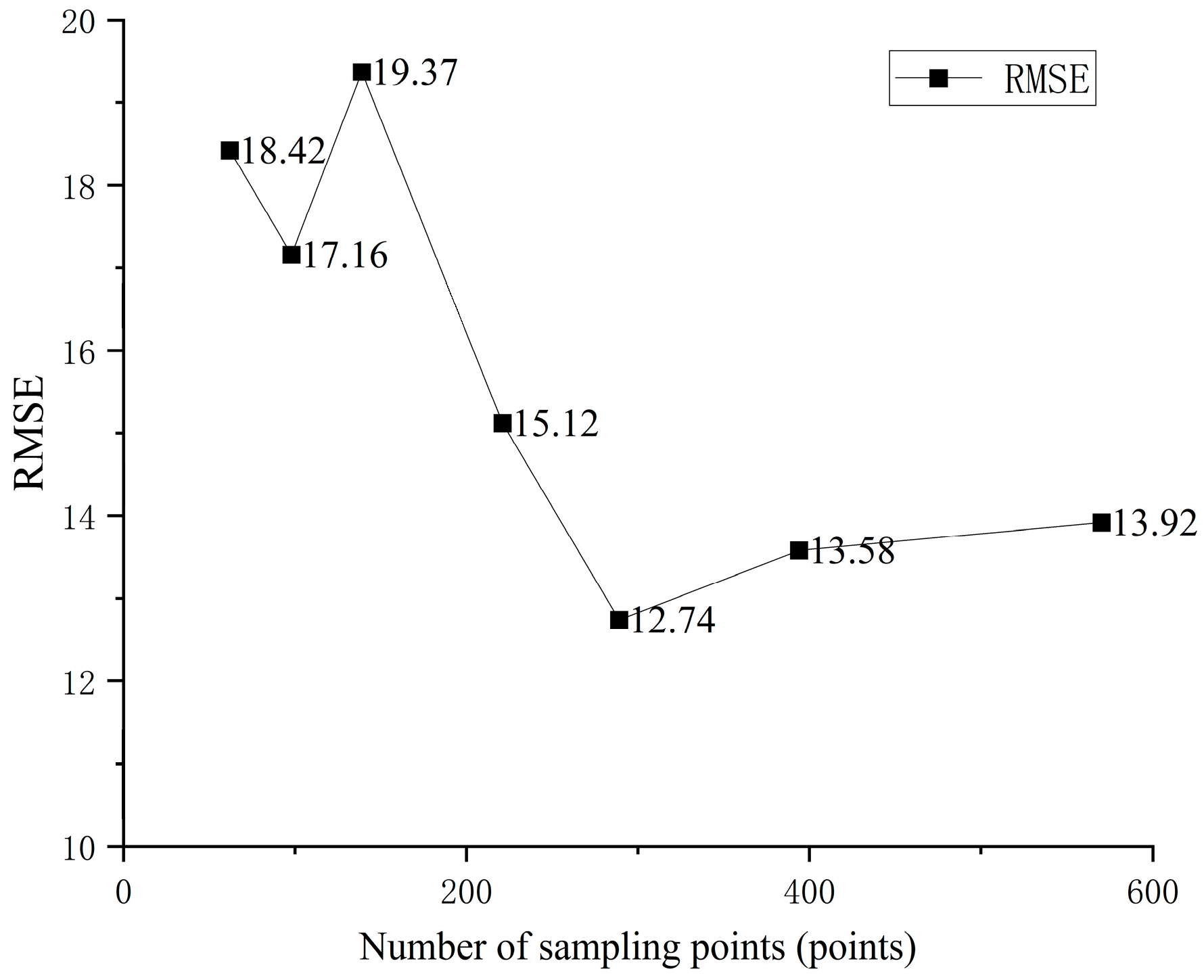

3.4. Optimal Sampling Density Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Arsenic in the Study Area Exhibits Enrichment Characteristics

4.2. The Dataset from the Study Area Exhibits a Pronounced Quadratic Polynomial Trend with Significant Directional Anisotropy

4.3. Sampling Density Is Not the Only Factor Affecting Spatial Variability in the Study Area. Considering Model Fitting Parameters, Spatial Distribution Patterns, and Cost–Benefit Analysis, a Moderate Sampling Density of 20 Points per Square Kilometer Represents the Optimal Monitoring Density

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Significant arsenic enrichment was observed in the study area, with concentrations reaching 3.6 times the national soil background value and 2.4 times the plateau soil background value.

- (2)

- Compared to arithmetic mean and median analyses, geometric mean evaluation demonstrates lower uncertainty across different sampling densities in ecological environment assessments, averaging 4.3%, and thus provides more accurate results.

- (3)

- Significant directional anisotropy exhibits a pronounced quadratic trend. Modeling spatial variation trends confirms that the strongest spatial correlation occurs along the northwest–southeast direction, with the spatial autocorrelation distance in the vertical direction reaching 2.39 times greater than in other directions.

- (4)

- Increasing sampling density is a macro-level requirement for accurately assessing the environmental risk characteristics of arsenic in plateau ecosystems. However, it is not the only factor influencing the spatial variability of arsenic concentrations. By comprehensively considering model fitting parameters, spatial distribution patterns, and cost–benefit analysis, a moderate sampling density of 20 points per square kilometer was determined to be the optimal monitoring density. This approach provides a monitoring framework for China’s Qinghai–Tibet Plateau and for developing countries with limited arable land and fragmented parcels.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wienhold, B.J.; Andrews, S.S.; Karlen, D.L. Soil quality: A review of the science and experiences in the USA. Environ. Geochem. Health 2004, 26, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, D.Y.; Jia, X.Y.; Wang, L.W.; McGrath, S.P.; Zhu, Y.G.; Hu, Q.; Zhao, F.J.; Bank, M.S.; O’Connor, D.; Nriagu, J. Global Soil Pollution by Toxic Metals Threatens Agriculture and Human Health. Science 2025, 388, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theocharopoulos, S.P.; Wagner, G.; Sprengart, J.; Mohr, M.E.; Desaules, A.; Muntau, H.; Christou, M.; Quevauviller, P. European soil sampling guidelines for soil pollution studies. In Science of the Total Environment; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; Volume 264, pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.C.; Jia, T.Z.; Peng, S.Z.; Yu, X.H.; She, D. Spatial distribution, source identification, and risk assessment of heavy metals in the cultivated soil of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau region: Case study on Huzhu County. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2022, 35, e02073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yang, J.; Min, Q.; Liu, M.C. Impacts of non-agricultural livelihood transformation of smallholder farmers on agricultural system in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2022, 20, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Wen, L.; Lu, H.; Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Xia, X.; Liao, Z.; Wangzha, D.; Zhaxi, W.; Tudan, J.; et al. Correction: Ecological, environmental risks and sources of arsenic and other elements in soils of Tuotuo River region, Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Environ. Geochem. Health 2024, 46, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Deng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Liang, M.; Lee, L.-C.; Cristhian, C.-O.; Yang, L.; He, T. Farmland phytoremediation in bibliometric analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X. Heavy metals remediation through lactic acid bacteria: Current status and future prospects. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, S.H.; Wang, K.Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.B.; Han, Y.Y. Risk Assessment System Based on WebGIS for Heavy Metal Pollution in Farmland Soils in China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.H.; Su, M.C.; Yeh, M.F.; Lin, W.J.; Yu, T.Y.; Yeh, M.C. Predicting and regulating potential zone for heavy metal re-contaminated farmland: Case study in Taiwan. Environ. Dev. 2025, 54, 101147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.T.; Dan, Z.; Cui, X.Q.; Zhang, R.X.; Zhou, S.Q.; Wenga, T.; Yan, B.B.; Chen, G.Y.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Zhong, L. Contamination, ecological and health risks of trace elements in soil of landfill and geothermal sites in Tibet. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 715, 136639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Sillanp, M.; Gjessing, E.T.; Vogt, R.D. Water Quality in the Southern Tibetan Plateau: Chemical Evaluation of the Yarlung Tsangpo (Brahmaputra). River Res. Appl. 2011, 27, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.W.; Pei, Q.M.; Yu, X.; Cao, A.B.; Chen, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, K.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.F. The long-lived partial melting of the Greater Himalayas in southern Xizang, constraints from the Miocene Gyirong anatectic pegmatite and its prospecting potential for rare element minerals. China Geol. 2023, 6, 303–321. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, R.G.; Chen, G.H.; Huang, X.; Tian, F.; Ni, L.F.; Peng, L.; Liao, D.Q.; Xi, B. Geochemical Characteristics of Tailings from Typical Metal Mining Areas in Tibet Autonomous Region. Minerals 2022, 12, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fendorf, S.; Michael, H.A.; van Geen, A. Spatial and Temporal Variations of Groundwater Arsenic in South and Southeast Asia. Science 2010, 328, 1123–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, A.T.; Ye, T.R.; Wang, Q.; Qiu, J.L.; Fang, B.; Yuan, G.L. Unraveling the behaviors and significances of waste biomass ashes as underlying emission sources of soil polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Hering, J.G. Comparison of Arsenic(V) and Arsenic(III) Sorption onto Iron Oxide Minerals: Implications for Arsenic Mobility. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 4182–4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Huang, X.; Ma, F.; Wang, L.; Duan, X.; Wang, S. Catalytic Removal of Aqueous Contaminants on N-Doped Graphitic Biochars: Inherent Roles of Adsorption and Nonradical Mechanisms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 8649–8658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.H.; Zhang, Z.X.; Yi, C. 3D fluorescence spectral data interpolation by using IDW. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2008, 71, 743–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.S.; Wang, J.; Xu, X.Y.; Fu, Y. Accumulation characteristics and risk assessment of Cr, Ni, As, Hg in urban soil of major cities in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 48, 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.S.; Han, S.; Wang, J.Y.; Tao, R.; Wang, R.; Liang, Y. Remediation effect and passivation mechanism of iron-modified biochar for arsenic and mercury co-contamination. Environ. Eng. Technol. 2025, 1–14. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=-PyPURV5YK0Amx5H7llzmtgD2Rlamz9cq5YSVPFQiUIjVSZx0tNKJhmmNSi7U8IPy2bye2CNzNI6db9YoJZnDWCJKCsqLGzcyeOm7Q537pR3EntQoJJB0XSMzsR0okcc8RseapCckfQYI_do7hENW9a9xvk3-z-n4ehfZYjoK4WfEY_lurH554Jar4dCmKqIZhGZtXfshHA&uniplatform=NZKPT&captchaId=a96fea26-7866-4166-ae42-0826154bfb19 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Bhandari, G.; Atreya, K.; Scheepers, P.T.J.; Geissen, V. Concentration and distribution of pesticide residues in soil: Non-dietary human health risk assessment. Chemosphere 2020, 253, 126594. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.; Li, F.C.; Zhang, Q.X.; Li, H.X.; Zhou, Y.Z.; Han, S.B.; Geng, H.J.; Li, H.Y. Characteristics, Ecological Risk Assessment, and Source Apportionment of Soil Heavy Metals in the Zhangbei County of the Plateau of Inner Mongolia. Environ. Sci. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, X.R.; Hu, Z.Q.; Ruan, M.Y.; Zhu, Q.; Sun, H. Remote-Sensing Evaluation and Temporal and Spatial Change Detection of Ecological Environment Quality in Coal-Mining Areas. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.D.; Cai, Y.K.; Zhu, K.; Wen, J.; Lu, Y.T. Spatial heterogeneity analysis and source identification of heavy metals in soil: A case study of Chongqing, Southwest China. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2022, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NS-ISO 18400-104:2018; Soil Quality–Sampling–Part 104: Strategies. Standard Norge: Lysaker, Norway, 2018.

- Yang, S.J.; Lee, B.T.; Kim, S.O.; Park, S.H. Review of microplastics in soils: State-of-the-art occurrence, transport, and investigation methods. J. Soils Sediments 2024, 24, 779–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, P.W.; Dong, N.; Lei, M.; Yang, S.C.; Gou, Y.L. An effective method for determining the optimal sampling scale based on the purposes of soil pollution investigations and the factors influencing the pollutants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 418, 126296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milillo, T.M.; Sinha, G.; Gardella, J.A., Jr. Use of geostatistics for remediation planning to transcend urban political boundaries. Environ. Pollut. 2012, 170, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.H.; Pu, L.J.; Xie, X.F.; Zhu, M.; Kan, B.Y.; Tan, Y.F. Review and Outlook of Designing of Soil Sampling for Digital Soil Mapping. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2020, 57, 259–272. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y.; Liu, H.B.; Wu, W. Evaluation to Soil Heavy Metals’ Pollution and the Study of Reasonable Sampling Number. Chin. J. Soil Sci. 2008, 2, 369–374. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Q.M.; Liu, Z.J.; Borders, B.E. Assessment of regression kriging for spatial interpolation–comparisons of seven GIS interpolation methods. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2013, 40, 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Z.C.; Sun, Z.J.; Xu, J.W.; Shi, H.D. Uncertainty analysis of regional cultivated land soil cadmium pollution assessment under different sampling densities. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2024, 43, 2545–2552. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Sun, J.K.; Chen, Y.P.; Xia, J.B. Spatial Variability of the Soil Heavy Metal with Different Sampling Scales. Chin. J. Soil Sci. 2009, 40, 1406–1410. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer, D.; Kiersch, K.; Baum, C.; Meissner, R.; Müller, R.; Jandl, G.; Leinweber, P. Scale-Dependent Variability of As and Heavy Metals in a River Elbe Floodplain. CLEAN-Soil Air Water 2011, 39, 319–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.S. Permafrost Carbon Release Risk Assessment in Qinghai Province Based on Multiple Permafrost Product Data Sets. Master’s Thesis, Qinghai Normal University, Xining, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, P.J.; Zhan, J.; Liu, J.; Li, X.Y.; Du, Y.P.; Wu, L.H.; Luo, Y.M. Research Progress on the Causes, Risks, and Control of High Geological Background of Heavy Metals in Soils. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2023, 60, 1363–1377. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 22105.2-2008; Soil quality—Analysis of Total Mercury, Arsenic and Lead Contents—Atomic Fluorescence Spectrometry—Part 2: Analysis of Total Arsenic in Soils. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2008.

- HJ/T 166-2004; Ministry of Environmental Protection of China. Technical Specification for Soil Environmental Monitoring. China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2004.

- Zhu, Z.H. Research on the Optimization Method of Soil Organic Matter Evaluation Points in Cultivated Land at the County Level. Master’s Thesis, Anhui University of Science and Technology, Huainan, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- GB 15618-2018; Ministry of Ecology and Environment & State Administration for Market Regulation. Soil Environmental Quality—Risk Control Standard for Soil Contamination of Agricultural Land. China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Zhang, Z.X.; Yu, Y.L.; Li, Y.Q.; Jiao, S.Y.; Dong, Z.; Han, G.D.; Xu, Z.Y. Effects of grazing intensity on soil organic carbon and its spatial heterogeneity in desert steppe of Inner Mongolia. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2021, 41, 6257–6266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokhana, D.B.; Kris, S.; Maria, O.D.; Eka, S.; Erma, S. Machine learning and topological kriging for river water quality data interpolation. AIMS Environ. Sci. 2025, 12, 120–136. [Google Scholar]

- Du, H.L.; Wang, J.S.; Wang, Y.; Yao, Y.B.; Liu, X.Y.; Zhou, Y. Contamination characteristics, source analysis, and spatial prediction of soil heavy metal concentrations on the qinghai-tibet plateau. J. Soils Sediments 2023, 23, 2202–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Lu, X.; Sai, N.; Liu, Y.; Du, W. Heavy metal concentrations in soil and ecological risk assessment in the vicinity of Tianzhu Industrial Park, Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. PeerJ 2024, 12, e18510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.T.; Zhang, C.C.; Wang, A.F.; Zhang, T.L.; He, Z.Y.; Zhao, Y.J.; Liu, B.W.J.; Zhou, Z.W. Research progress on environmental behavior of arsenic in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau soil. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 153, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.L. Predictive modeling and risk assessment of soil-maize transport of cadmium and arsenic in the active state in upland areas. Beijing Jiaotong Univ. 2023, 153, 237–250. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, S.L.; Wang, L.Y.; Liu, T.C. Study of solidification and stabilization of heavy metals by passivators in heavy metal-contaminated soil. Open Chem. 2022, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China National Environment Monitoring Centre. Background Values of Soil Elements in China; China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.; Wu, C.; Zeng, D.M.; Cheng, X.M.; Sun, B.B. Distribution of Heavy Metals and Ecological Risk of Soils in the Typical Geological Background Region of Southwest China. Rock Miner. Anal. 2021, 40, 384–396. [Google Scholar]

- Reimann, C.; Garrett, R.G. Geochemical background- concept and reality. Sci. Total Environ. 2005, 350, 12–27. [Google Scholar]

- Göd, R.; Zemann, J. Native arsenic-realgar mineralization in marbles from Saualpe, Carinthia, Austria. Mineral. Petrol. 2000, 70, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.L.; Gao, W.H.; Wei, T.; Dong, Z.W.; Shao, Y.P. Distribution characteristics of heavy metals in Tibetan Plateau surface soils and its significance for source tracing of heavy metal deposition in surrounding glacial areas. China Environ. Sci. 2024, 44, 2198–2207. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Yu, Y.L.; Ding, S.Y.; Dai, W.J.; Shi, R.G.; Cui, G.Y. Application of machine learning in soil heavy metals pollution assessment in the southeastern Tibetan plateau. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelwall, M. The precision of the arithmetic mean, geometric mean and percentiles for citation data: An experimental simulation modelling approach. J. Informetr. 2016, 10, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abyani, M.; Asgarian, B.; Zarrin, M. Sample geometric mean versus sample median in closed form framework of seismic reliability evaluation: A case study comparison. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2019, 18, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smothers, C.D.; Sun, F.; Dayton, A.D. Comparison of arithmetic and geometric means as measures of a central tendency in cattle nematode populations. Vet. Parasitol. 1999, 81, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, R.M. The geometric mean? Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods 2022, 51, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, F.; Gomes, M.I. The total median statistic to monitor contaminated normal data. Qual. Technol. Quant. Manag. 2016, 13, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, W.R.; Reimer, K.J. Arsenic speciation in the environment. Chem. Rev. 1989, 89, 713–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Xu, Z.F.; Fan, P.K.; Zhou, Z.W. Enrichment of arsenic in the Yarlung Tsangpo basin, Southern Tibetan Plateau: Provenance, process, and link with tectonic setting. Appl. Geochem. 2024, 165, 105964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Zhang, Y.C.; Yang, Z.S.; Li, Z.Q.; Liu, Y.C.; Liu, Y.F.; Liu, Q.Y.; Sun, Q.Z.; Fu, Q.; Hou, Z.Q. Multiphase and polystage metallogenic process of the Zhaxikang large-size Pb-Zn-Ag-Sb polymetallic deposit in southern Tibet and its implications. Acta Petrol. Et Mineral. 2014, 33, 64–78. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, G.L.; Gui, X.X.; Song, L.Q.; Li, M.; Cui, X.F.; Tian, X.M. Soil Geochemical Characteristics and Prospecting Potential of the Daweng Gold Mine in Eastern Xizang. Geol. Explor. 2023, 59, 1204–1216. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.T.; Wang, J.T.; Xia, X.P.; Ci, L.; Luosang, J.C.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, J.T.; Liang, H.Y. The key constrations on large-scale mineralization of Cenozoic potassic alkaline rocks in the Eastern Tibet-Sanjiang Belt. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2025, 41, 693–710. [Google Scholar]

- Man, J.; Chen, Y.; Fan, H.; Chen, Q.; Yao, Y. Optimizing Soil Sampling with Information. Entropy at Heavy-Metal Sites. ACS EST Eng. 2023, 3, 1350–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.Y.; Duan, L.X.; Xie, H.X.; Hu, B.F.; Zhou, Q.; Luo, J. Determination of Reasonable Sample Density for Spatial Interpolation of Soil Organic Matter in Cultivated Land of County Region Based on Conditional Latin Hypercube Sampling. Chin. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 53, 505–513. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Du, H.F.; Wu, K.N.; Jiang, H.L.; Liu, P.J.; Xu, W.W. Suitable Interpolation Method and Reasonable Sampling Quantity of Cd Pollution Index in Soil. Chin. J. Soil Sci. 2016, 47, 1056–1064. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, X.Z.; Zheng, H.W.; He, R.C.; Ding, W.J.; Zhang, J.; Cui, G.N.; Shi, P.L.; Xie, Y.F. Optimal grid scale and sampling design optimization method for heavy metal pollution investigation in farmland soil. J. Environ. Eng. Technol. 2021, 11, 861–868. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.W.; Feng, J.; Liu, G.; Zhang, T.J. Multi-nesting Spatial Scales of Soil Heavy Metals in Farmland. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2013, 44, 128–135. [Google Scholar]

| Acceptable Relative Deviation Value | Number of Sampling Points per Sample (n) | Number of Samples per Sample Set | Number of Sample Sets | Sampling Density (Points/km2) | Estimated Sampling Costs (¥) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.05 | 570 | 30 | 10 | 29 | 17,400 |

| 0.06 | 394 | 30 | 10 | 20 | 12,000 |

| 0.07 | 289 | 30 | 10 | 15 | 9000 |

| 0.08 | 221 | 30 | 10 | 11 | 6600 |

| 0.10 | 139 | 30 | 10 | 7 | 4200 |

| 0.12 | 98 | 30 | 10 | 5 | 3000 |

| 0.15 | 62 | 30 | 10 | 3 | 1800 |

| Level | Risk Characteristics | Number of Sample Points | Percentage (%) | National Arsenic Background Values in Soil | Background Arsenic Levels in Tibetan Soils |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | Low risk | 192 | 31.2 | 11.2 mg/kg | 18.6 mg/kg |

| Level 2 | Moderate risk | 397 | 64.9 | ||

| Level 3 | High risk | 23 | 3.7 |

| Number of Sampling Points (Points) | Optimal Model | Coefficient of Determination (R2) | Spatial Variation Ratio Co/(Co + C) | Range (a) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 62 | Gaussian model | 0.327 | 0.974 | 2710 |

| 98 | Spherical model | 0.409 | 0.933 | 1471 |

| 139 | Spherical model | 0.456 | 0.824 | 1921 |

| 221 | Gaussian model | 0.555 | 0.846 | 2512 |

| 289 | exponential Model | 0.658 | 0.889 | 2911 |

| 394 | Spherical model | 0.753 | 0.875 | 2271 |

| 570 | Spherical model | 0.761 | 0.900 | 3527 |

| 612 | Spherical model | 0.856 | 0.719 | 4503 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, Y.; Wu, H.; Ma, T.; Yang, K.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, R.; Wangjiu, D.; Deji, Z. Uncertainty Analyses of Arsenic Element Assessments in Cultivated Soils at Different Sampling Densities in High-Altitude Regions. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2755. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122755

Yu Y, Wu H, Ma T, Yang K, Guo J, Zhang Z, Shi R, Wangjiu D, Deji Z. Uncertainty Analyses of Arsenic Element Assessments in Cultivated Soils at Different Sampling Densities in High-Altitude Regions. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2755. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122755

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Yilong, Hongwei Wu, Tiantian Ma, Ke Yang, Jinghao Guo, Ziheng Zhang, Rongguang Shi, Dawa Wangjiu, and Zhaxi Deji. 2025. "Uncertainty Analyses of Arsenic Element Assessments in Cultivated Soils at Different Sampling Densities in High-Altitude Regions" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2755. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122755

APA StyleYu, Y., Wu, H., Ma, T., Yang, K., Guo, J., Zhang, Z., Shi, R., Wangjiu, D., & Deji, Z. (2025). Uncertainty Analyses of Arsenic Element Assessments in Cultivated Soils at Different Sampling Densities in High-Altitude Regions. Agronomy, 15(12), 2755. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122755