Implications of Weedy Rice in Various Smallholder Transplanting Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

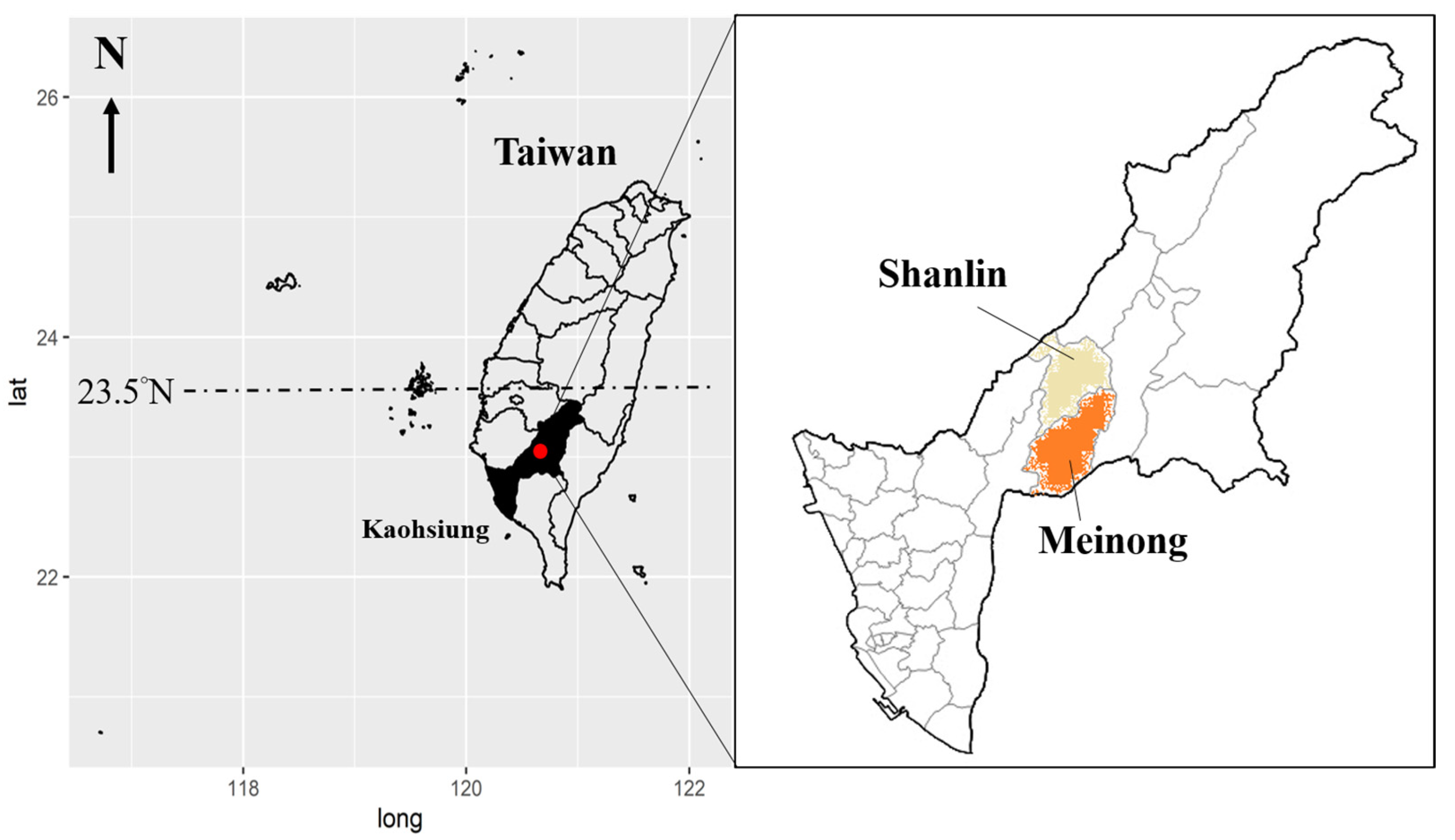

2.1. Samples Collection and Grouping

2.2. Sample Processing

2.3. Data Analysis and Visualization

3. Results

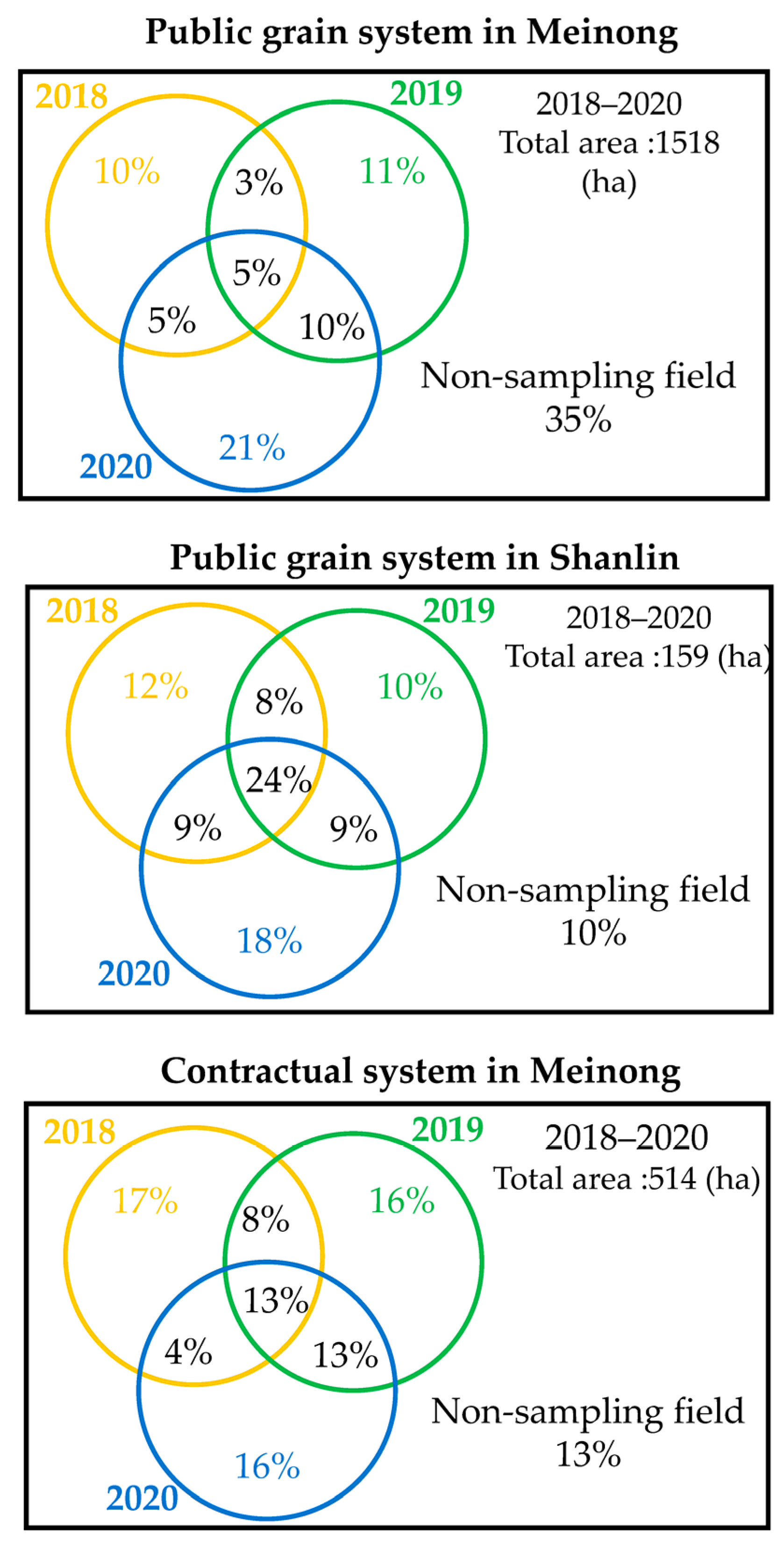

3.1. Weedy Rice Contamination and Management

3.1.1. Weedy Rice Contamination

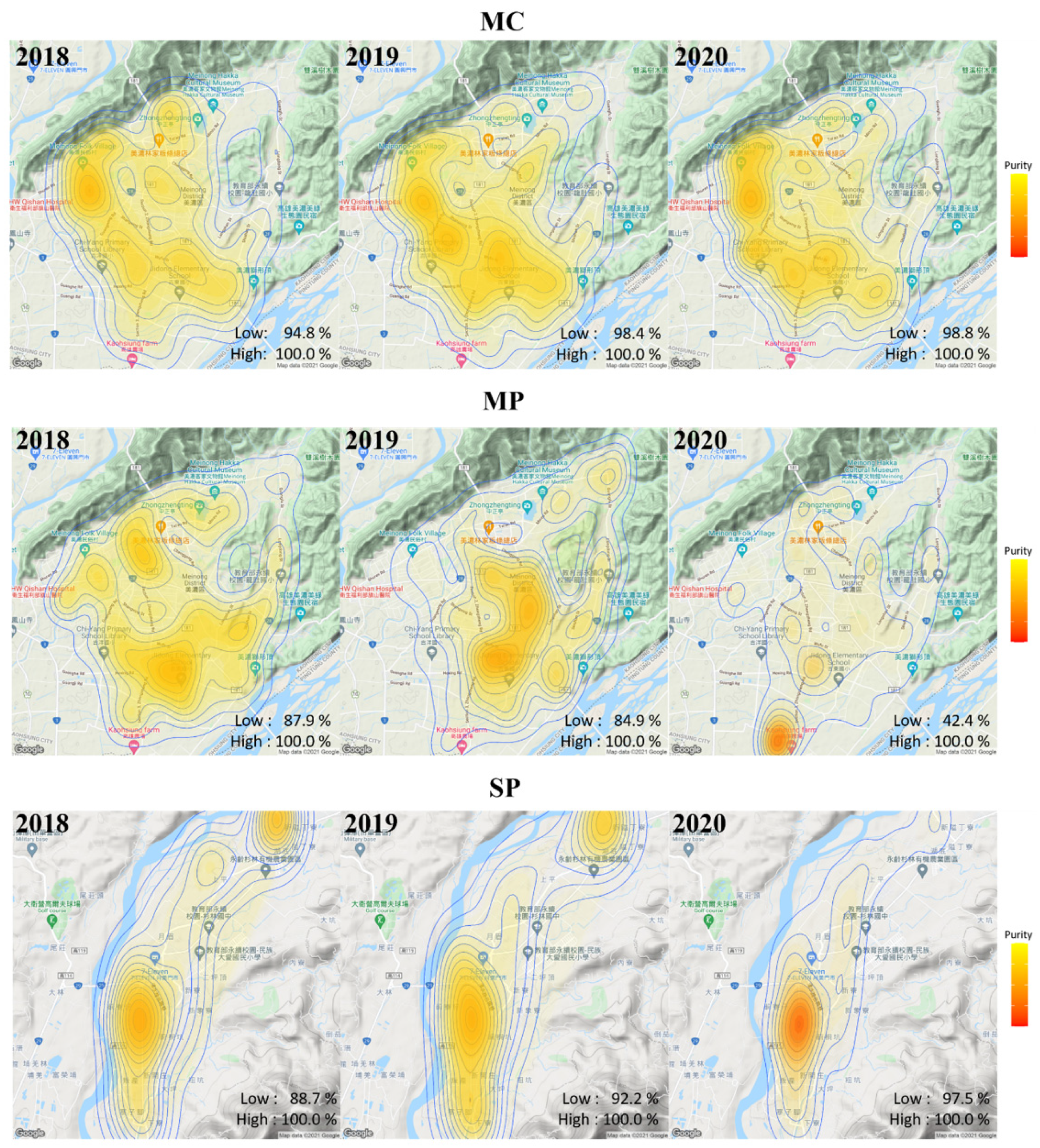

3.1.2. Geographical Distribution of Weedy Rice Contamination

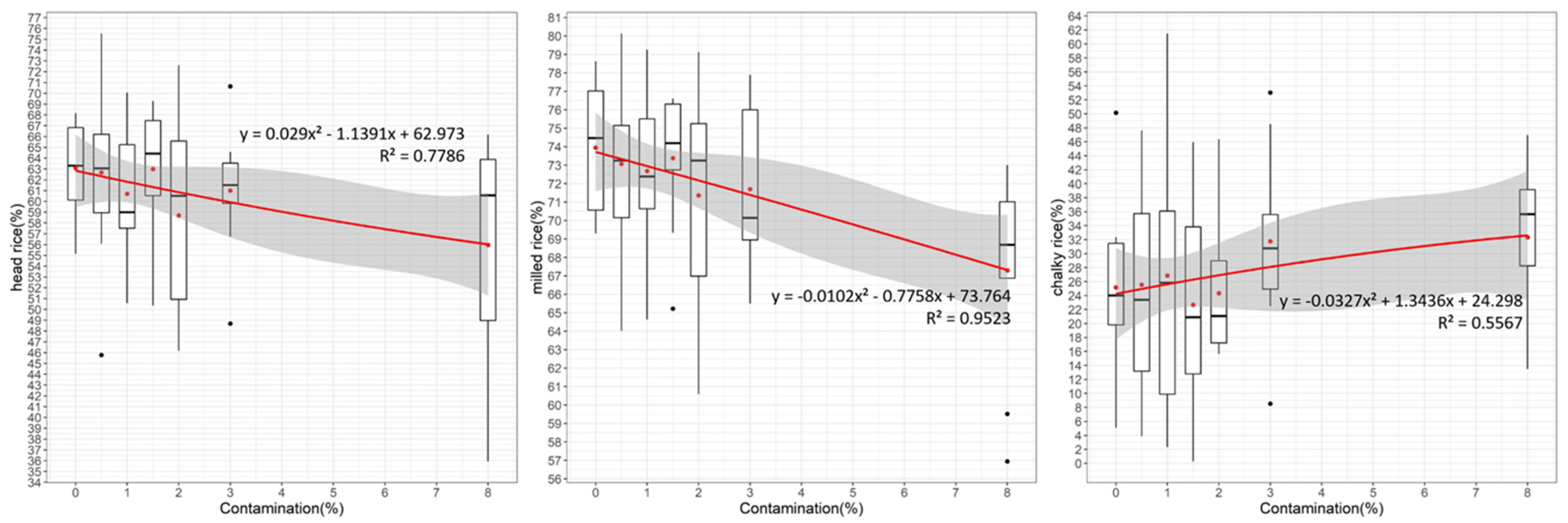

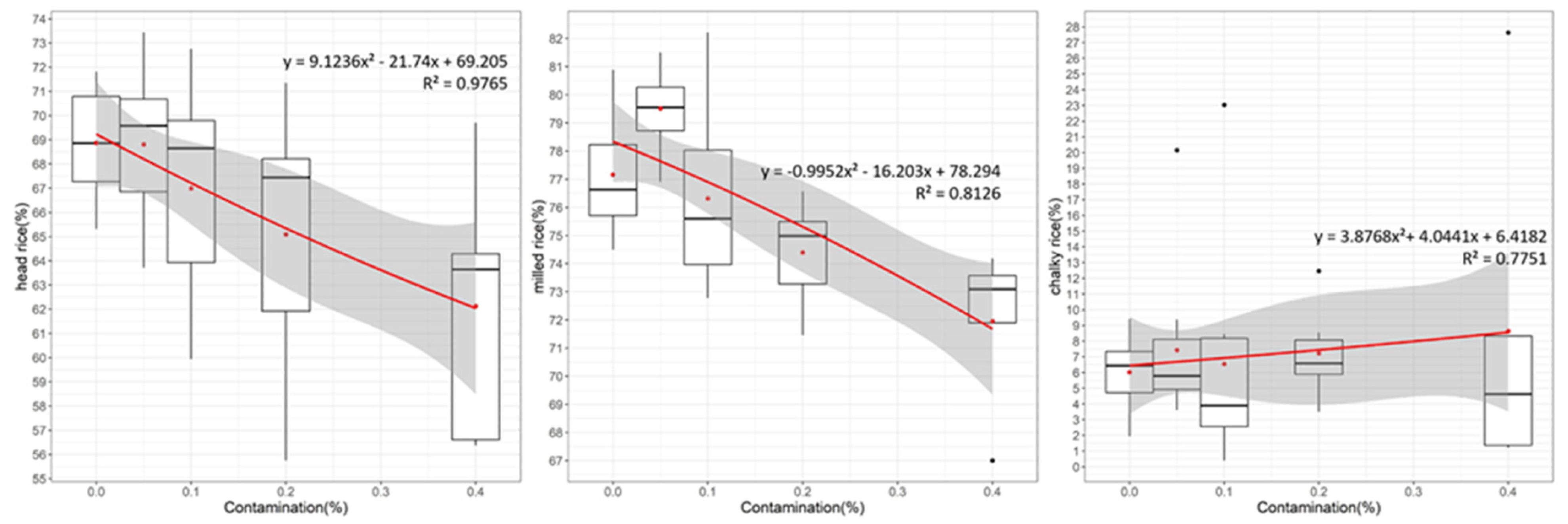

3.2. Weedy Rice Contamination and Grain Quality

4. Discussion

4.1. Weedy Rice Management and Agricultural Practices

4.1.1. Seed-Mediated Contamination

4.1.2. Soil Seed Bank

4.1.3. Pollen-Mediated Contamination

4.2. Grain Quality and Variety

4.3. Benefit of IWMS

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CPS | Clearfield rice production system |

| DSR | Direct-seeded rice |

| IWMS | Integrated Weed Management System |

| KH147 | Kaohsiung 147 |

| MC | Meinong Contractual |

| MP | Meinong Public Stock |

| SP | Shanlin Public Stock |

| TT30 | Taitung 30 |

| TWR | Taiwan weedy rice |

References

- Durand-Morat, A.; Nalley, L.L. Economic Benefits of Controlling Red Rice: A Case Study of the United States. Agronomy 2019, 9, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.H.; Gealy, D.R.; Jia, M.H.; Edwards, J.D.; Lai, M.H.; McClung, A.M. Phylogenetic Origin and Dispersal Pattern of Taiwan Weedy Rice. Pest Manag. Sci. 2020, 76, 1639–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos, N.R.; Norman, R.J.; Gealy, D.R.; Black, H. Competitive N Uptake between Rice and Weedy Rice. Field Crops Res. 2006, 99, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogliatto, S.; Ferrero, A.; Vidotto, F. How Can Weedy Rice Stand Against Abiotic Stresses? A Review. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, B.S.; Singh, K.; Ladha, J.K.; Kumar, V.; Saharawat, Y.S.; Gathala, M. Weedy Rice: An Emerging Threat for Direct-Seeded Rice Production Systems in India. J. Rice Res. 2013, 1, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Jiang, X.; Ratnasekera, D.; Grassi, F.; Perera, U.; Lu, B.R. Seed-Mediated Gene Flow Promotes Genetic Diversity of Weedy Rice within Populations: Implications for Weed Management. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaizumi, T. Weedy Rice Represents An Emerging Threat to Transplanted Rice Production Systems in Japan. Weed Biol. Manag. 2018, 18, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.C.; Wu, D.H.; Chen, S.W.; Castillo, S.A.C.; Huang, S.D.; Li, C.P.; Wang, Y.P. Insights into the Genetic Spatial Structure of Nicaraguan Weedy Rice and Control of its Seed Spread. Pest Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 3685–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noldin, J.A.; Chandler, J.M.; McCauley, G.N. Seed Longevity of Red Rice Ecotypes Buried in Soil. Planta Daninha 2006, 24, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, J.A. ‘With Grains in Her Hair’: Rice in Colonial Brazil. Slavery Abolit. 2004, 25, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Song, B.K.; Li, L.F.; Li, Y.L.; Huang, Z.; Caicedo, A.L.; Jia, Y.; Olsen, K.M. Little White Lies: Pericarp Color Provides Insights into the Origins and Evolution of Southeast Asian Weedy Rice. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2016, 6, 4105–4114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongtamee, A.; Maneechote, C.; Pusadee, T.; Rerkasem, B.; Jamjod, S. The Dynamics of Spatial and Temporal Population Genetic Structure of Weedy Rice (Oryza sativa f. spontanea Baker). Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2017, 64, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londo, J.P.; Schaal, B.A. Origins and Population Genetics of Weedy Red Rice in the USA. Mol. Ecol. 2007, 16, 4523–4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.F.; Wu, D.H.; Wang, C.L.; Du, P.R.; Cheng, C.Y.; Cheng, C.C. Survey of Rice Production Practices and Perception of Weedy Red Rice (Oryza sativa f. spontanea) in Taiwan. Weed Sci. 2021, 69, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, G.; Yu, H.; Qiang, S. The Within-Field and Between-Field Dispersal of Weedy Rice by Combine Harvesters. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 38, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilipkumar, M.; Kumar, V.; Song, B.; Olsen, K.M.; Chuah, T.; Ahmed, S.; Qiang, S. Weedy Rice (Oryza spp.). In Biology and Management of Problematic Crop Weed Species; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 285–309. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, B.S.; Abeysekera, A.S.; Wickramarathe, M.S.; Kulatunga, S.D.; Wickrama, U.B. Effect of Rice Establishment Methods on Weedy Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Infestation and Grain Yield of Cultivated Rice (O. sativa L.) in Sri Lanka. Crop Prot. 2014, 55, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadir, S.; Xiong, H.B.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, X.L.; Xu, H.Y.; Li, J.; Dongchen, W.; Henry, D.; Guo, X.Q.; Khan, S.; et al. Weedy Rice in Sustainable Rice Production. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 37, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurber, C.S.; Reagon, M.; Olsen, K.M.; Jia, Y.; Caicedo, A.L. The Evolution of Flowering Strategies in US Weedy Rice. Am. J. Bot. 2014, 101, 1737–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svizzero, S. Weedy Rice and the Protracted Initial Domestication of Asian Rice. Acad. Lett. 2021, 2, 2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.T.; Wang, Y.C.; Du, P.R.; Li, C.P.; Wu, D.H. Morphological Diversity and Crop Mimicry Strategies of Weedy Rice Under the Transplanting Cultivation System. Agronomy 2025, 15, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.B.; Wang, W.; Xia, H.; Zhao, W.; Lu, B.R. Conspecific Crop-Weed Introgression Influences Evolution of Weedy Rice (Oryza sativa f. spontanea) Across A Geographical Range. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, N.; Wang, Z.; Song, Z.J.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.S.; Bao, Y.; Lu, B.R. Origins of Weedy Rice Revealed by Polymorphisms of Chloroplast DNA Sequences and Nuclear Microsatellites. J. Syst. Evol. 2021, 59, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gealy, D.R.; Mitten, D.H.; Rutger, J.N. Gene Flow between Red Rice (Oryza sativa) and Herbicide-Resistant Rice (O. sativa): Implications for Weed Management. Weed Technol. 2003, 17, 627–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merotto Jr, A.; Goulart, I.C.; Nunes, A.L.; Kalsing, A.; Markus, C.; Menezes, V.G.; Wander, A.E. Evolutionary and Social Consequences of Introgression of Nontransgenic Herbicide Resistance from Rice to Weedy Rice in Brazil. Evol. Appl. 2016, 9, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.C. Rice Production in Taiwan: Evolution and Policies. In Taiwan Rice History; Deng, Y.Z., Li, C.L., Li, R.X., Eds.; Chinese Agronomy Press: Taipei, Taiwan, 1999; pp. 19–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ihaka, R.; Gentleman, R. R: A Language for Data Analysis and Graphics. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 1996, 5, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4. Available online: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Kahle, D.; Wickham, H. ggmap: Spatial Visualization with ggplot2. R J. 2013, 5, 144–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pebesma, E. Simple features for R: Standardized support for spatial vector data. R J. 2018, 10, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bivand, R.; Keitt, T.; Rowlingson, B.; Pebesma, E.D.Z.E.R.; Sumner, M.; Hijmans, R. Rgdal: Bindings for the Geospatial Data Abstraction Library; R Package Version 2019; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2019; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2016; Available online: http://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- de Mendiburu, F. Agricolae Tutorial; Version 1.3-5; Universidad Nacional Agraria: La Molina, Peru, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary, A.K.; Thakur, R.C.; Kumar, N. Effect of Integrated Nutrient Management on Soil Physical and Hydraulic Properties in Rice-Wheat Crop Sequence in NW Himalayas. Indian J. Soil Conserv. 2008, 36, 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Dass, A.; Shekhawat, K.; Choudhary, A.K.; Sepat, S.; Rathore, S.S.; Mahajan, G.; Chauhan, B.S. Weed Management in Rice Using Crop Competition-A Review. Crop Prot. 2017, 95, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraibar, B.; Westerman, P.R.; Carrión, E.; Recasens, J. Effects of Tillage and Irrigation in Cereal Fields on Weed Seed Removal by Seed Predators. J. Appl. Ecol. 2009, 46, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Burgos, N.R.; Singh, S.; Gealy, D.R.; Gbur, E.E.; Caicedo, A.L. Impact of Volunteer Rice Infestation on Yield and Grain Quality of Rice. Pest Manag. Sci. 2017, 73, 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, B.S. Strategies to Manage Weedy Rice in Asia. Crop Prot. 2013, 48, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Patra, B.C.; Munda, S.; Mohapatra, T. Weedy Rice: Problems and Its Management. Indian Soc. Weed Sci. 2014, 46, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Marahatta, S.; Chaudhary, S.K.; Gyawaly, P.; Sah, S.K.; Karki, T.B. Ecological Weed Management Practices and Seedbed Preparation Optimized the Yield of Dry Direct Seeded Rice in Sub-Humid Condition of Chitwan, Nepal. J. Agric. For. Univ. 2017, 1, 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, M.; Baral, B.; Dulal, P.R. A Review on Weed in Direct Seeded Rice (DSR). Sustain. Food Agric. 2021, 2, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.L.; Delatorre, C.A.; Merotto, A., Jr. Gene Expression Related to Seed Shattering and the Cell Wall in Cultivated and Weedy Rice. Plant Biol. 2014, 16, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Xu, W.; Song, X.; Dai, W.; Dai, L.; Zhang, Z.; Qiang, S. Early Flowering and Rapid Grain Filling Determine Early Maturity and Escape from Harvesting in Weedy Rice. Pest Manag. Sci. 2018, 74, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogliatto, S.; Vidotto, F.; Ferrero, A. Effects of Winter Flooding on Weedy Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Crop Prot. 2010, 29, 1232–1240. [Google Scholar]

- Mansor, M.; Karim, S.R.; Abidin, Z. Effects of Farmers’ Cultural Practices on the Weedy Rice Infestation and Rice Production. Sci. Res. Essays 2012, 7, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mispan, M.S.; Bzoor, M.; Mahmod, I.; Md-Akhir, A.H.; Zulrushdi, A. Managing Weedy Rice (Oryza sativa L.) in Malaysia: Challenges and Ways Forward. J. Res. Weed Sci. 2019, 2, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Bhullar, M.S.; Chauhan, B.S. Influence of Tillage, Cover Cropping, and Herbicides on Weeds and Productivity of dry Direct-Seeded Rice. Soil Tillage Res. 2015, 147, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narwal, S.; Sindel, B.M.; Jessop, R.S. Tillage and Residue Burning Affects Weed Populations and Seed Banks. Commun. Agric. Appl. Biol. Sci. 2006, 71, 715–723. [Google Scholar]

- Vidotto, F.; Ferrero, A. Interactions between Weedy Rice and Cultivated Rice in Italy. Ital. J. Agron. 2009, 4, 127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, C.T.; Jose, N. Weedy Rice Invasion in Rice Fields of India and Management Options. J. Crop Weed 2014, 10, 365–374. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, J. Rice Milling Quality. In Rice; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 339–369. [Google Scholar]

- de Avila, L.A.; Noldin, J.A.; Mariot, C.H.; Massoni, P.F.; Fipke, M.V.; Gehrke, V.R.; Merotto, A., Jr.; Tomita, F.M.; Matos, A.B.; Facioni, G.; et al. Status of Weedy Rice (Oryza spp.) Infestation and Management Practices in Southern Brazil. Weed Sci. 2021, 69, 536–546. [Google Scholar]

- Bzour, M.I.; Zuki, F.M.; Mispan, M.S. Introduction of Imidazolinone Herbicide and Clearfield® Rice between Weedy Rice—Control Efficiency and Environmental Concerns. Environ. Rev. 2018, 26, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture. Annual Report of 2020 Agricultural Statistics. 2020. Available online: https://agrstat.moa.gov.tw/sdweb/public/book/Book.aspx (accessed on 11 May 2025).

| Factor | Sub-Factor | IWMS | Meinong Contractual | Meinong Public | Shanlin Public | WR Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic condition | Cultivar | KH147 | TT30 | TT30 | ||

| Management | Following certain regulation under contractual system | Smallholder not following certain regulation | Smallholder not following certain regulation | |||

| Grain quality requirement | High level | No certain requirement | No certain requirement | |||

| First crop season | Source of seedlings | Before IWMS | Purchased from certain nurseries using certified seed | Purchased from numerous nurseries using uncertified seeds or some farmers saved seeds by themselves | Purchased from a few nurseries using uncertified seeds | Seed mediated contamination |

| After IWMS | Purchased from certain nurseries using certified seed | Some purchased from nurseries using certified seed, some purchased from nurseries using normal seed | Purchased from certain nurseries using certified seed | |||

| Agricultural implement | Sharing with neighbors in a small area | Sharing with growers across a big area | Sharing with neighbors in a small area | |||

| Land preparation | Dry tillage | Dry tillage | Dry tillage | Seedlings from soil seed bank | ||

| Crop | Rice | Rice | Rice | |||

| Cropping system | Transplanting | Transplanting | Transplanting | |||

| Number of preemergent herbicide application times | Before IWMS | 1 | 0–1 | 1 | ||

| After IWMS | 2 | 0–1 | 2 | |||

| Second crop season | Number of weedings | 1–2 | 0–1 | 0–1 | ||

| Land preparation | Before IWMS | No-tillage | Dry tillage | Dry tillage | ||

| After IWMS | Wet-tillage | Dry tillage | Wet tillage or dry tillage | |||

| Cropping system (crop) | Fallowing | Rotation (green manure) | Rotation (green manure) | |||

| Inter-season | Cropping system (crop) | Rotation (red bean) | Fallowing | Fallowing | ||

| Acceptance of IWMS | Enforce | Median | High | |||

| Awareness of weedy rice invasion | High | Low | Median | |||

| Group | Total Area (ha) | Year | Thousand-Grain Weight of Brown Rice (g) | Seed Lot | Land Parcel | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seed Lot Number | Contamination (‰) | Clean Field | Land Parcel Number | Sampling Area (ha) | Sampling Area Coverage (%) † | ||||||||

| Mean ± SD | Min | Median | Max | Field Number | Proportion (%) | ||||||||

| MC | 300 | 2018 | 21.3 | 274 | 0.76 ± 3.23 | 0.00 | 0.31 | 52.22 | 98 | 35.77 | 1040 | 206.62 | 68.87 |

| 2019 | 20.3 | 309 | 0.73 ± 1.12 | 0.00 | 0.56 | 16.43 | 49 | 15.86 | 1250 | 245.37 | 81.79 | ||

| 2020 | 21.0 | 270 | 0.45 ± 1.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 11.93 | 142 | 52.59 | 1176 | 224.73 | 74.91 | ||

| MP | 1200 | 2018 | 22.7 | 679 | 11.30 ± 15.33 | 0.00 | 5.85 | 121.23 | 72 | 10.60 | 1890 | 347.00 | 28.92 |

| 2019 | 21.6 | 735 | 6.90 ± 12.17 | 0.00 | 3.14 | 143.11 | 24 | 3.27 | 2322 | 417.42 | 34.79 | ||

| 2020 | 23.7 | 1162 | 6.30 ± 44.56 | 0.00 | 0.48 | 575.49 | 250 | 21.51 | 3628 | 630.63 | 52.55 | ||

| SP | 130 | 2018 | 24.7 | 129 | 18.11 ± 16.31 | 0.00 | 15.28 | 113.16 | 2 | 1.55 | 429 | 78.79 | 60.61 |

| 2019 | 24.2 | 129 | 10.58 ± 13.12 | 0.00 | 6.20 | 77.49 | 5 | 3.88 | 424 | 79.18 | 60.91 | ||

| 2020 | 22.1 | 165 | 1.59 ± 2.94 | 0.00 | 0.80 | 25.25 | 9 | 5.45 | 486 | 92.70 | 71.31 | ||

| Cultivar | Contamination (‰) | Number of Samples | Milled Rice Rate (%) | Head Rice Rate (%) | Chalky Kernel Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KH147 | 0 | 10 | 73.32 ± 2.67 a† | 68.87 ± 2.20 a | 9.02 ± 7.69 a |

| 0–1 | 13 | 71.99 ± 2.34 a | 68.89 ± 2.69 a | 6.53 ± 4.75 a | |

| 1–2 | 9 | 73.30 ± 2.67 a | 66.72 ± 4.08 a | 6.85 ± 6.52 a | |

| 2–3 | 2 | 74.69 ± 2.63 a | 65.77 ± 7.90 a | 4.60 ± 5.57 a | |

| 3–4 | 3 | 70.89 ± 3.63 a | 58.88 ± 4.70 b | 11.51 ± 14.14 a | |

| >4 | 3 | 72.86 ± 0.86 a | 63.24 ± 6.67 b | 4.77 ± 3.48 a | |

| TT30 | 0 | 15 | 72.19 ± 3.91 a | 63.10 ± 3.73 a | 24.84 ± 11.17 a |

| 0–10 | 39 | 69.90 ± 3.85 b | 60.73 ± 5.82 a | 28.40 ± 13.90 a | |

| 10–20 | 20 | 73.01 ± 4.99 a | 62.02 ± 6.73 a | 25.24 ± 15.45 a | |

| 20–30 | 14 | 70.49 ± 4.24 a | 58.58 ± 7.22 a | 26.32± 9.83 a | |

| 30–40 | 4 | 71.71 ± 4.34 a | 61.57 ± 2.14 a | 42.09 ± 10.38 a | |

| >40 | 8 | 67.35 ± 5.92 b | 55.37 ± 10.51 b | 31.92 ± 12.66 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hsu, Y.-T.; Ting, C.-Y.; Du, P.-R.; Li, C.-P.; Wu, D.-H. Implications of Weedy Rice in Various Smallholder Transplanting Systems. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2754. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122754

Hsu Y-T, Ting C-Y, Du P-R, Li C-P, Wu D-H. Implications of Weedy Rice in Various Smallholder Transplanting Systems. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2754. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122754

Chicago/Turabian StyleHsu, Yi-Ting, Chih-Yun Ting, Pei-Rong Du, Charng-Pei Li, and Dong-Hong Wu. 2025. "Implications of Weedy Rice in Various Smallholder Transplanting Systems" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2754. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122754

APA StyleHsu, Y.-T., Ting, C.-Y., Du, P.-R., Li, C.-P., & Wu, D.-H. (2025). Implications of Weedy Rice in Various Smallholder Transplanting Systems. Agronomy, 15(12), 2754. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122754