Small Peptide Fertilizers Derived from Instant Catapult Steam Explosion Technology: Molecular Characterization and Agronomic Efficacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Prepare SPFs from three distinct protein sources (fish, soybean meal, and slaughterhouse sheepskin) using ICSE under optimized processing parameters;

- (2)

- Systematically characterize the molecular, chemical, and nutritional properties of the resulting SPFs through advanced analytical techniques, including gel permeation chromatography, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, and HPLC/LC-MS;

- (3)

- Evaluate the effects of ICSE-derived SPFs on growth, yield, and nitrogen use efficiency in rice and rapeseed through carefully designed field trials.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of SPFs

2.3. Characteristics of SPFs

2.4. Design of Field Experiment

2.4.1. Test Site Environment

2.4.2. Experimental Design

2.4.3. Determination of Plant Growth Indicators: N Uptake, Grain Yield, and Nitrogen Use Efficiency

2.4.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

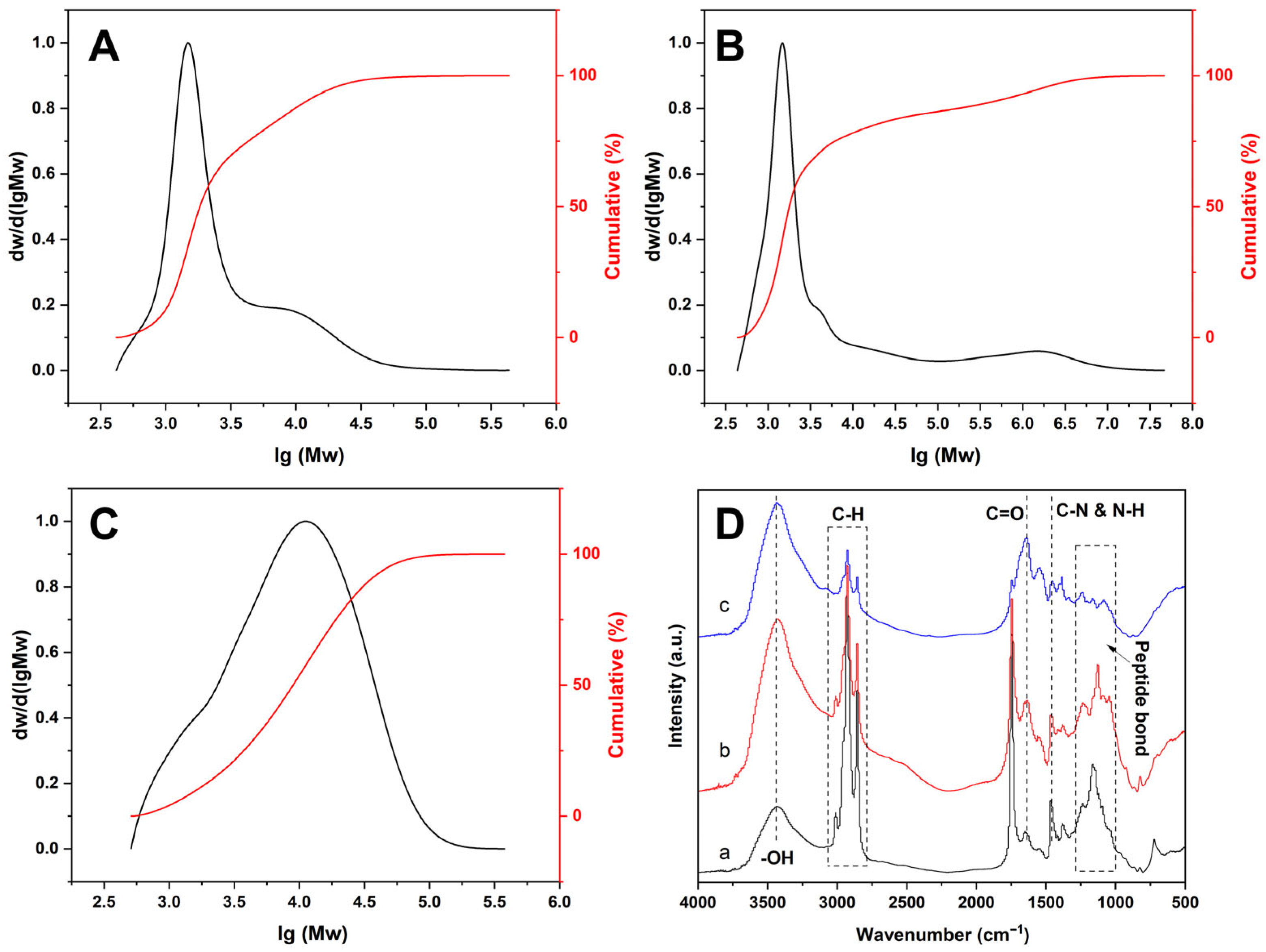

3.1. Molecular Weight Distribution of SPFs

3.2. Infrared Spectroscopy Analysis of SPFs

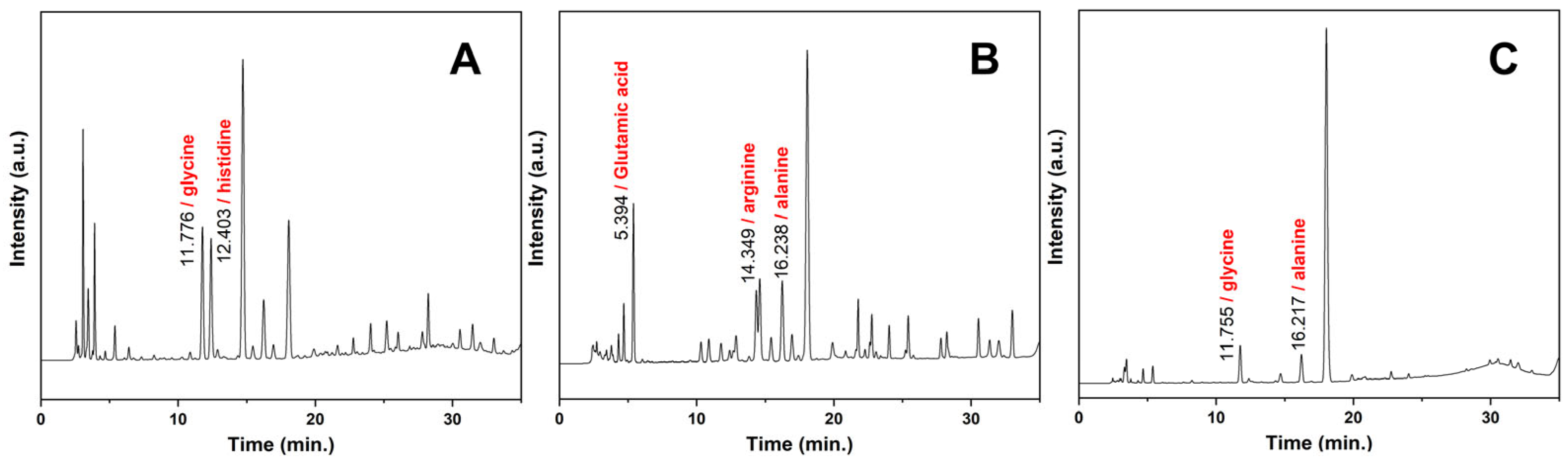

3.3. Component Analysis of SPFs

3.4. Effects on the Growth of Rice and Rapeseed

3.5. Effects on the Yield and NUE of Rice and Rapeseed

4. Discussion

4.1. Advantages of ICSE Technology in SPF Preparation: Comparison with Traditional Methods and Parameter Optimization

4.2. Correlation Between SPF Molecular–Chemical Properties and Raw Material Characteristics

4.3. Growth Promotion of SPFs in Rice and Rapeseed

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, C.; Pan, J.J.; Lam, S.K. A review of precision fertilization research. Environ. Earth Sci. 2014, 71, 4073–4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.L.; Liu, Z.M.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, W.; Mou, H.J. Production of a water-soluble fertilizer containing amino acids by solid-state fermentation of soybean meal and evaluation of its efficacy on the rapeseed growth. J. Biotechnol. 2014, 187, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.Q.; Xiao, F. Small Peptides: Orchestrators of Plant Growth and Developmental Processes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellens, R.P.; Brown, C.M.; Chisnal, M.A.W.; Waterhouse, P.M.; Macknight, R.C. The Emerging World of Small ORFs. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, S.; Deng, F.; Zhou, W.; Wang, L.; Li, W.; Hu, H.; Pu, S.L.; Li, S.X.; Chen, Y.; Tao, Y.F.; et al. Polypeptide urea increases rice yield and nitrogen use efficiency through root growth improvement. Field Crop Res. 2024, 313, 109415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panthi, U.; McCallum, B.; Kovalchuk, I.; Rampitsch, C.; Badea, A.; Yao, Z.; Bilichak, A. Foliar application of plant-derived peptides decreases the severity of leaf rust (Puccinia triticina) infection in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2024, 22, 100357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Zhang, J.; Jia, C.H.; Feng, J.J.; Liang, L.D.; Cheng, Q.S.; Li, T.; Hao, J.H. Foliar application of fish protein peptide improved the quality of deep-netted melon. J. Plant Nutr. 2023, 46, 3683–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.Q.; Liu, Z.C.; Liu, Y.J.; Su, Z.J.; Liu, Y.G. Plant polypeptides: A review on extraction, isolation, bioactivities and prospects. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 207, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyüz, A.; Tekin, I.; Aksoy, Z.; Ersus, S. Plant Protein Resources, Novel Extraction and Precipitation Methods: A Review. J. Food Process Eng. 2024, 47, e14758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Sun, Y.F.; Li, Y.W.; Ye, Z.H.; Lin, H.B.; Yang, K. Overview of the preparation method, structure and function, and application of natural peptides and polypeptides. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 153, 113493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somehsaraie, M.H.A.; Vavsari, V.F.; Kamangar, M.; Balalaie, S. Chemical Wastes in the Peptide Synthesis Process and Ways to Reduce Them. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2022, 21, e14758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Casas, D.E.; Aguilar, C.N.; Ascacio-Valdes, J.A.; Rodriguez-Herrera, R.; Chavez-Gonzalez, M.L.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C. Enzymatic hydrolysis and microbial fermentation: The most favorable biotechnological methods for the release of bioactive peptides. Food Chem. 2021, 3, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Augustin, O.; Rivero-Gutiérrez, B.; Mascaraque, C.; de Medina, F.S. Food Derived Bioactive Peptides and Intestinal Barrier Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 22857–22873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li-Chan, E.C.Y. Bioactive peptides and protein hydrolysates: Research trends and challenges for application as nutraceuticals and functional food ingredients. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2015, 1, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.D.; Zhang, B.L.; Yu, F.Q.; Xu, G.Z.; Song, A.D. A real explosion: The requirement of steam explosion pretreatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 121, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquet, N.; Maniet, G.; Vanderghem, C.; Delvigne, F.; Richel, A. Application of Steam Explosion as Pretreatment on Lignocellulosic Material: A Review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2015, 54, 2593–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Sun, X.; Dong, J.; Wu, L.; Guo, W.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, M. Instant catapult steam explosion pretreatment of wheat straw liquefied polyols to prolong the slow-release longevity of bio-based polyurethane-coated fertilizers. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 435, 134985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Y.; Pan, Y.G.; Zheng, L.L.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, X.Y.; Ai, B.L.; Xu, Z.M.; Sheng, Z.W. Application of steam explosion in oil extraction of camellia seed (Camellia oleifera Abel.) and evaluation of its physicochemical properties, fatty acid, and antioxidant activities. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 1004–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.W.; Guo, T.T.; Huang, Q.D.; Shi, X.W.; Zhou, X. Preparation of high-quality concentrated fragrance flaxseed oil by steam explosion pretreatment technology. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 2112–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Li, Z.M.; Wang, Z.M.; Mao, G.T.; Zhang, H.S.; Wang, F.Q.; Chen, H.G.; Yang, S.; Tsang, Y.F.; Lam, S.S.; et al. Instant Catapult Steam Explosion: A rapid technique for detoxification of aflatoxin-contaminated biomass for sustainable utilization as animal feed. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 255, 120010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 19541-2017; Feed Raw Material: Soybean Meal. National Standard of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Zhang, H.R.; Liu, H.; Qi, L.W.; Xv, X.; Li, X.; Guo, Y.J.; Jia, W.; Zhang, C.H.; Richel, A. Application of steam explosion treatment on the collagen peptides extraction from cattle bone. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2023, 85, 103336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, W.Y.; Cheng, J.R.; Liu, J.J.; Pei, W.X.; Wang, J.F.; Chuang, S.C. Amino acid fertilizer strengthens its effect on crop yield and quality by recruiting beneficial rhizosphere microbes. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 5970–5980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, L.; Richardson, G.; Melo, P.; Barroca, N. The hidden power of glycine: A small amino acid with huge potential for piezoelectric and piezo-triboelectric nanogenerators. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 510, 161514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, S.X.; Hu, C.Y.; Chen, X.J.; Sun, X.; Xu, N.J. Physiological and Transcriptome Analysis of Exogenous L-Arginine in the Alleviation of High-Temperature Stress in Gracilariopsis lemaneiformis. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 784586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NY/T 3831-2021; Organic Water-Souluble Fertilizers: General Regulations. Chinese Agricultural Industry Standard (CAIS): Beijing, China, 2021.

- Hong, H.; Fan, H.B.; Chalamaiah, M.; Wu, J.P. Preparation of low-molecular-weight, collagen hydrolysates (peptides): Current progress, challenges, and future perspectives. Food Chem. 2019, 301, 125222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neklyudov, A.D.; Ivankin, A.N.; Berdutina, A.V. Properties and uses of protein hydrolysates (Review). Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2000, 36, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-M.; Ye, D.-X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Zhou, Y.-L.; Zhang, L.; Yang, X.-L. Peptides, new tools for plant protection in eco-agriculture. Adv. Agrochem 2023, 2, 58–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, M.; Bleakley, S. Peptides from plants and their applications. In Peptide Applications in Biomedicine, Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 603–622. [Google Scholar]

- Chalamaiah, M.; Dinesh kumar, B.; Hemalatha, R.; Jyothirmayi, T. Fish protein hydrolysates: Proximate composition, amino acid composition, antioxidant activities and applications: A review. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 3020–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, R.C.; Yu, Q.Q.; Shen, Y.; Chu, Q.; Chen, G.; Fen, S.Y.; Yang, M.X.; Yuan, L.; McClements, D.J.; Sun, Q.C. Production, bioactive properties, and potential applications of fish protein hydrolysates: Developments and challenges. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 110, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Bi, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Ramadan, N.S.; Zheng, R.; Wang, Y.; Yang, B. Structure and activity of bioactive peptides produced from soybean proteins by enzymatic hydrolysis. Food Chem. Adv. 2022, 1, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, X.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, L. Soy Protein: Molecular Structure Revisited and Recent Advances in Processing Technologies. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 12, 119–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkness, M.W.H.; Lehmann, K.; Forde, N.R. Mechanics and structural stability of the collagen triple helix. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2019, 53, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matinong, A.M.E.; Pickering, K.L.; Waterland, M.R.; Chisti, Y.; Haverkamp, R.G. Gelatin and Collagen from Sheepskin. Polymers 2024, 16, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamm, P.; Lim, M.H.; Hochstrasser, R.M. Structure of the amide I band of peptides measured by femtosecond nonlinear-infrared spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 6123–6138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, B.; Shin, K.H.; Kim, S.K. Muscle Protein Hydrolysates and Amino Acid Composition in Fish. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, I.; Dauksas, E.; Remme, J.F.; Richardsen, R.; Løes, A.-K. Fish and fish waste-based fertilizers in organic farming–With status in Norway: A review. Waste Manag. 2020, 115, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhu, L.P.; Wang, H.Q.; Zhou, X.; Wang, M.H.; Li, L.B.; Liu, F.; Sun, J.; Xiao, G.H. Peptide Hormone-Mediated Regulation of Plant Development and Environmental Adaptability. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e06590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, L.; Cakebread, J.A.; Loveday, S.M. Food proteins from animals and plants: Differences in the nutritional and functional properties. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 119, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oztug, M. Bioactive Peptide Profiling in Collagen Hydrolysates: Comparative Analysis Using Targeted and Untargeted Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry Quantification. Molecules 2024, 29, 2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stührwohldt, N.; Schaller, A. Regulation of plant peptide hormones and growth factors by post-translational modification. Plant Biol. 2019, 21 (Suppl. 1), 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Raw Materials | Water/Raw Material Ratio | Pressure (MPa) | Time (min) | Label |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish | - | 1.4 | 8 | SPF1 |

| Soybean meal | 4 | 1.2 | 6 | SPF2 |

| Slaughterhouse sheepskin | 0.6 | 1.4 | 8 | SPF3 |

| pH | Organic Matter g kg−1 | TP g kg−1 | AP mg kg−1 | AK mg kg−1 | Total N g kg−1 | NO3-N mg kg−1 | NH4+-N mg kg−1 | Clay g kg−1 | Silt g kg−1 | Sand g kg−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7.85 | 10.1 | 0.89 | 10.2 | 102.5 | 0.809 | 5.24 | 17.2 | 297.0 | 353.0 | 78.5 |

| Treatment | N (mg g−1) | P2O5 (mg g−1) | K2O (mg g−1) | Total Free Amino Acids (mg g−1) | Small Peptide Content (mg g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPF1 | 14.9 ± 0.8 a | 0.3 ± 0.06 a | 0.29 ± 0.01 a | 0.478 ± 0.08 a | 573 ± 14 a |

| SPF2 | 15.1 ± 0.9 a | 0.2 ± 0.04 a | 0.23 ± 0.03 b | 0.462 ± 0.02 a | 421 ± 18 b |

| SPF3 | 11.4 ± 0.8 b | 0.2 ± 0.05 a | 0.15 ± 0.01 c | 0.366 ± 0.05 b | 386 ± 10 c |

| Treatment | Plant Height (cm) | SPAD | Flag Leaf Length (cm) | Flag Leaf Width (cm) | Flag Leaf Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F + W | 114.3 ± 2.2 b | 42.1 ± 0.9 b | 29.5 ± 1.1 c | 1.39 ± 0.06 b | 30.75 ± 0.7 b |

| F + SPF1 | 120.1 ± 2.6 a | 47.4 ± 1.1 a | 34.3 ± 1.3 a | 1.46 ± 0.03 a | 50.11 ± 1.1 a |

| F + SPF2 | 119.9 ± 1.9 a | 43.7 ± 0.9 b | 30.3 ± 1.2 c | 1.45 ± 0.04 a | 32.95 ± 0.7 b |

| F + SPF3 | 119.4 ± 3.2 a | 46.3 ± 1.1 a | 32.4 ± 0.9 b | 1.44 ± 0.05 a | 34.98 ± 0.9 b |

| Treatment | Plant Height (cm) | SPAD | Height of Effective Branches (cm) | Number of Primary Effective Branches | Number of Secondary Effective Branches | Silique Length (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F + W | 119.3 ± 2.1 b | 42.1 ± 0.8 b | 30.4 ± 1.3 a | 9.7 ± 1.3 b | 12.9 ± 1.4 b | 4.9 ± 0.02 b |

| F + SPF1 | 122.5 ± 2.4 a | 45.5 ± 0.9 a | 24.2 ± 1.5 c | 11.3 ± 1.2 a | 14.6 ± 1.3 a | 6.1 ± 0.04 a |

| F + SPF2 | 123.8 ± 2.4 a | 45.3 ± 0.7 a | 26.5 ± 0.9 b | 11.1 ± 1.6 a | 14.1 ± 1.6 a | 5.7 ± 0.03 a |

| F + SPF3 | 123.6 ± 2.9 a | 44.4 ± 1.1 a | 26.9 ± 1.3 b | 9.8 ± 1.4 b | 13.8 ± 1.2 ab | 5.6 ± 0.06 a |

| Treatment | Number of Ears Per Mu | Number of Effective Grains Per Ear | 1000-Grain Weight (g) | Yield (kg hm−2) | Yield Increase Rate | NUE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F + W | 18.98 ±1.4 b | 130.45 ± 3.8 b | 24.2 ± 0.2 c | 8405 ± 50.2 c | - | 38.4 |

| F + SPF1 | 20.32 ± 1.7 a | 155.42 ± 4.1 a | 27.5 ± 0.4 a | 9276 ± 53.3 a | 10.36% | 42.3 |

| F + SPF2 | 19.11 ± 1.1 a | 141.71 ± 4.1 a | 27.1 ± 0.3 a | 8793 ± 51.7 a | 4.62% | 41.2 |

| F + SPF3 | 19.75 ± 1.2 a | 145.38 ± 4.1 a | 27.6 ± 0.6 a | 8902 ± 67.1 a | 5.91% | 42.4 |

| Treatment | Number of Effective Siliques | Number of Effective Siliques | 1000-Grain Weight (g) | Yield (kg Per Mu) | Yield Increase Rate (%) | NUE (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Main Inflorescence Siliques | Number of Siliques on Primary Branches | Number of Siliques on Secondary Branches | Total Number of Siliques Per Plant | ||||||

| F + W | 51.2 ± 1.3 c | 304.4 ± 1.9 b | 204.3 ± 1.4 a | 559.9 ± 18.3 b | 22.4 ± 2.2 b | 3.96 ± 0.1 a | 171.2 ± 8.4 c | - | 39.6 |

| F + SPF1 | 71.2 ± 1.7 a | 373.2 ± 4.1 a | 199.7 ± 2.1 a | 644.2 ± 9.6 a | 25.5 ± 2.7 a | 3.99 ± 0.2 a | 191.3 ± 11.4 a | 11.74 | 43.4 |

| F + SPF2 | 65.3 ± 2.1 b | 314.3 ± 2.6 b | 185.3 ± 1.1 b | 564.9 ± 8.7 b | 22.1 ± 1.9 b | 3.97 ± 0.1 a | 184.3 ± 15.1 b | 7.65 | 40.3 |

| F + SPF3 | 52.4 ± 1.5 c | 309.6 ± 3.2 b | 205.4 ± 2.2 a | 567.4 ± 10.5 b | 22.2 ± 26 b | 3.96 ± 0.1 a | 174.3 ± 9.9 c | 1.81 | 39.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, X. Small Peptide Fertilizers Derived from Instant Catapult Steam Explosion Technology: Molecular Characterization and Agronomic Efficacy. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2734. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122734

Liu X, Yu Z, Zhang J, Zhao X. Small Peptide Fertilizers Derived from Instant Catapult Steam Explosion Technology: Molecular Characterization and Agronomic Efficacy. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2734. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122734

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xiaoqi, Zhengdao Yu, Jie Zhang, and Xu Zhao. 2025. "Small Peptide Fertilizers Derived from Instant Catapult Steam Explosion Technology: Molecular Characterization and Agronomic Efficacy" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2734. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122734

APA StyleLiu, X., Yu, Z., Zhang, J., & Zhao, X. (2025). Small Peptide Fertilizers Derived from Instant Catapult Steam Explosion Technology: Molecular Characterization and Agronomic Efficacy. Agronomy, 15(12), 2734. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122734